James Hammond had been waiting to become a soldier since the beginning of the war. He had spent his childhood in Morgan Township, less than a mile from the Ohio River in Gallia County, watching as slaves brought from Kentucky worked on local farms. Over the years he had talked with some of the bondsmen and witnessed the capture of and brutality toward those who attempted to run away. He vowed that when he came of age he would join the Union army in order to help end their plight. On March 6, 1864, just a week before his eighteenth birthday, he became a member of Company F of the 27th United States Colored Troops. Early that year the Christian Recorder proudly boasted that blacks were enlisting at a faster rate than the white population.1

Critical backing for Ohio’s involvement in the USCT came from the black community members’ desire to obtain their own civil, economic, and political equality, as well as the abolition of slavery for their Southern brethren. Local, state, and sometimes national leaders organized recruiting rallies and speeches in several Ohio communities. Prominent blacks encouraged men to enlist and for churches, neighbors, and families to support them. Black supporters of military participation also wrote editorials and plastered broadsides in various towns urging black men to volunteer. Some advocates attempted to shame potential recruits into doing their manly duty. The Weekly Anglo-African, a widely read black New York newspaper that printed both religious and political news, warned readers that “the eyes of the whole world are upon you, civilized man everywhere waits to see if you will prove yourselves … Will you vindicate your manhood?”2 Ohioans like Hammond and others from very different backgrounds rose to the challenge. They joined the army for diverse reasons, based on their numerous and varying hopes for their own future as well as for their family, and for some, for all people of color. The Civil War presented blacks with the opportunity to make individual decisions and to act in their own self-interest in ways previously denied or made difficult for them. While only white politicians and military leaders had the power to legitimize African American military participation, Northern blacks made conscious choices that shaped their involvement.

Overall, Union volunteers tended to be single farmers born in the United States. But there was no truly “typical” white Northern soldier. Likewise, the men in the 27th lacked homogeneity. Members of the USCT were likely to be dark-skinned, young, Southern-born slaves who performed agricultural labor, but this description falls short of explaining the vast differences among the black recruits. The soldiers’ ages varied greatly, and they came from a myriad of backgrounds. Despite the long-held belief that the black race was an inferior lot, their presence in the Union army forced a closer public examination of the men as individuals. This observation and the reluctant acceptance of black males into the military complicated the attempt by Northern society to create the image of a typical soldier who could serve as a patriotic and heroic symbol of the United States. As the war evolved from what many perceived to be a movement to preserve the nation to one that would restructure the citizenry in order to create a more perfect Union, the presence of black troops provided tangible evidence that African Americans could be worthy soldier-citizens. While the conflict required society to tolerate involvement and assistance from groups that previously would have been denied a similar public role, such as the wartime contributions of women, it was largely understood that these adjustments would be only temporary changes. The recognition of Northern free black men as capable and needed military participants forced the socially constructed ideals of gender, class, and race to be reconsidered, especially as it became evident that many of the men who served in the USCT had somewhat similar characteristics to the ideal soldier’s image whites used to help justify and sustain the devastating war.3

The majority of men who served in the 27th USCT tended to be young, with reported ages that ranged from seventeen to forty-five. There were soldiers who exaggerated their age, including at least two who were sixteen and another who was only fourteen. This was not uncommon, and it occurred in other black and white regiments. Thomas Jefferson Tabler told recruiters he was seventeen, although it would be several months before the Athens County private actually reached that age. The provost marshal rejected George W. Bryan for “being under age,” despite the boy’s claim that he was a nineteen-year-old bookkeeper from Xenia. Gaston Cableton of Monroe County listed his age as eighteen when he volunteered, but less than three months later officials reported that the sixteen-year-old had died. Some older men also misrepresented their age, especially after the War Department announced in September 1862 that no enlistees over the age of forty-five would be accepted. The 27th mustered in eighty soldiers who stated their ages were between forty and forty-five. Forty-two-year-old Charles Higgins enlisted in Cleveland in February 1865 and served with the regiment until it returned to Ohio in September. Charles Julius told recruiters that he was forty-five when he joined in January 1864. By September Capt. Isaac N. Gardner recommended that the Stark County resident be discharged for “imperfect vision of both eyes,” and Gardner also claimed that Julius was sixty years old. Officials did not accept all of the older volunteers. In September 1864 the Ohio Board of Inspectors rejected Tennessee-born William Chambers, defending their decision based on the Revised Army Regulations of 1863 and Circular 67 released a month earlier. After their examination of the self-proclaimed forty-two-year-old, they denied his enlistment due to “infirm old age” and underlined their additional stated evidence that “his hair was dyed black previous to enlistment.”4

For the most part, though, the men’s ages in the 27th were fairly representative of all Northern soldiers and all USCT. The average recorded age in the regiment at enlistment was almost twenty-five years. Just over 43.5 percent of the soldiers reported their age as twenty-one and under, and only 21.6 percent said they were thirty and over. The most common age stated at muster in was eighteen. General statistics for the USCT overall indicate an average age of just under twenty-six years, with 26 percent aged thirty and over, and the most frequent age at enlistment was eighteen. For comparison, Northern soldiers as a whole had a medium age of twenty-four years by 1864, with 40 percent under the age of twenty-one and 25 percent aged thirty years and over. The largest single age group when recruited for all Union men was also eighteen years of age.5

But a closer examination of the regiment reveals a greater age difference when compared to the statistics of the “average” Northern soldier. When looking at the age of substitutes in the 27th, an even more youthful group can be defined. Although the most common age for men who joined because they were paid to replace a draftee was eighteen, the average age was twenty-two. Just over 65 percent of all substitutes were twenty-one or younger, and only 11 percent were aged thirty or over. Drafted men in the regiment, on the other hand, tended to be older. The average age of a conscripted soldier in the 27th was twenty-nine years. There were no eighteen-year-olds, more than 84 percent of those forced to join the regiment were over twenty-one, and almost 49 percent of the men were aged thirty and over. One explanation for the age difference is that more of the older men were married with children and some had established occupations. They made choices that best served their economic and familial status and joined only if drafted. The young men without the obligations and probably limited training could benefit from the steady pay and sought the adventurous aspects of military life. Therefore, more chose to be substitutes.6

The soldiers’ prewar domestic lives differed slightly from those of the average Northerner, white or USCT. Most men in the 27th lived in rural areas or small towns, reflecting both the state’s black population and the nation as well. Overall, more blacks were native born than were white Northern troops. Immigrants made up roughly 25 percent of the Union army, whereas they totaled 30 percent of the population in the North. In Ohio 85 percent of the 1860 white population was native born, while 99.75 percent of the blacks who served in the 27th USCT were born in the United States. Only five soldiers in the regiment, including twenty-five-year-old substitute Andrew Jackson Carter, who within one year rose to the rank of sergeant of Company K, told officers that they were born out of the country. All reported Canada as their place of birth. In the USCT overall, just over 8 percent were born in the North, and in the 27th almost 31 percent of the enlistees reported being born in a free state.7

Even though only 27 percent of the men in the regiment were born in Ohio, compared to 60 percent of whites in the state, most became lifetime residents once they came to the Buckeye State. Few of these blacks joined the pattern of many nineteenth-century Americans who moved west again after spending time in the state. Migration around the lower half the state was common, though, especially along Ohio’s two canal routes, as the men looked for work. For younger men and older boys this often meant leaving their families. As a result, many single black men lived with others or in boardinghouses. Henry Carter resided with Fanny Miles and her three children in Urbana when he enlisted. The twenty-seven-year-old from Tennessee signed up for service in Company A only a few days after Fanny’s son John had volunteered. This experience of leaving their families to live with others probably made joining the service less daunting for some of the new recruits.8

Nonetheless, most soldiers lived in family units before they enlisted. The large number of eighteen-year-olds in the regiment meant that most were single, as was typical for most other Northern soldiers, white or black. The young farmer John Elder, for instance, who had moved to Ohio from Kentucky in the late 1850s, lived with his parents and nine siblings in Highland County when he joined at the age of eighteen. On the other hand, the majority of those over thirty, and many who were younger, were married and most of them had children. William Darlington, aged forty-four, from Portsmouth, had a wife and two school-age children when he enlisted in Company B for three years. William P. Kinney, a twenty-nine-year-old laborer and runaway slave from Kentucky, married his wife Martha Jane in Highland County in 1861. Soon they had a son, also William, and in June 1864 Kinney received a $100 bounty when he volunteered for service.9

Like other unskilled workers in Ohio, the men who joined the 27th in 1864–1865 tended to be financially unstable. Most worked as day or farm laborers, like William Mayberry of Fayette County. After his father died in 1859, he worked for wages on a local farm to support his mother and younger siblings. He also rented land that he tilled; his combined earnings were about $18 a month. But for most African Americans, the average income was closer to $11 a month, and between 66 to 80 percent of the free black population lived in this financial situation. Officials recorded on volunteer enlistment and substitute forms that 47.6 percent of the men in the 27th were laborers and almost 39 percent farmers or farm laborers. Although a few of the farmers actually owned their own land, most were like John W. Phillips. He and his widowed mother farmed a piece of land owned by the Sweringen family in Pickaway County. When he had free time, he did day labor for neighbors. His brother, Gibson, worked as a day laborer in nearby Circleville. His mother “put out” his sister Rachel to domestic work in the community, but Rachel still considered the family dwelling as her home. Gibson joined the 5th USCT in 1863, and a year later Maria said good-bye to her second son when a white widower with young children paid John to be his substitute after he was drafted. John enlisted in Company H in May 1864. Like John, almost 86.5 percent of the men in the 27th were either laborers and farmers or unskilled workers. This data is slightly higher than the projected employment data on the USCT as a whole, in which 70 to 80 percent of black soldiers are listed as unskilled farm workers or laborers. The difference is considerably greater when compared with white soldiers, for whom officers recorded the occupations as 47.5 percent farmer and farm laborers, just fewer than 25 percent skilled workers, and almost 17 percent semiskilled workers.10

These differences can be explained by several factors. The African American day laborer in Ohio worked in both farm and nonfarm jobs as they became available. Like white workers, blacks in Ohio might perform farm labor in the spring and fall and then seek manual work in more populated areas during the other times of the year. The work or occupation therefore depended on when the recruit mustered in. Furthermore, the men who joined the 27th were the last in the state to enter the Union army. Approximately three thousand Ohio blacks had already enlisted in the 54th and 55th Massachusetts, the 5th USCT, and several other regiments. Also, army officers recording the information often made assumptions about the incoming black soldiers that were not accurate. For example, the company musters and descriptive rolls for Company E listed Simon P. Pleasant, aged thirty-one, as a laborer. Other records indicate he had been a farmer living with his wife Amelia and their three children in Ross County before he enlisted. Kentucky-born James H. Payne, who mustered into the 27th on March 8, 1864, served as a deacon and minister for the AME and signed all of his correspondence as “Rev. James H. Payne,” yet the Company G descriptive books listed his prewar occupation as a laborer.11

Some of the men reported semiskilled or skilled occupations, such as barber, blacksmith, plasterer, boatman and sailor, mason, or coopers. John D. White, aged twenty-two, worked as a fireman in Cincinnati before joining the USCT in February 1864. James H. Taylor was a thirty-one-year-old barber when he enlisted for three years in late March. The 12.8 percent of semiskilled and skilled positions reported by the men in the 27th is similar to the overall USCT livelihoods, where artisans made up the next largest group after farm and day laborers. Domestics, mariners, and the smallest group, small business owners and professionals, followed. Only a few men in the 27th fell into this category, such as Payne’s work as a minister before entering service. The limited number of skilled and professional positions had to do in part with the inadequate economic resources and restricted educational opportunities for blacks in Ohio. Simpson Younger of Company A was attending the Oberlin preparatory school when he enlisted in January 1864, but officers failed to record this on his muster-in and descriptive rolls.12

The reality, though, was that few lived in communities with a large enough population to support black businesses. Those in a more stable financial situation looked at the inequitable compensation of black soldiers during the first year after the creation of the USCT as a serious deterrent to enlistment. In Company A, the occupations for the eighty-four men who mustered in before May 1864 included seventy-eight laborers, one farmer, and five unknown. Many of the men who had professional, skilled, or semiskilled occupations waited to join in the summer of 1864 or later, when equal pay, substitution, and bounties put less strain on their financial concerns. The jobs listed for the fifty-one men who joined Company A after July 1864 represented all of these areas, including barber Silas McIntosh from Washington County and Jethro Davison, who worked as a blacksmith in Butler County when he enlisted as a substitute. Davison continued his trade on detached duty for the quartermaster’s department during the war.13

The most noticeable and defining difference between Northern soldiers was obviously the color of their skin. Nineteenth-century Americans used race, a socially constructed category based on biological differences, as a tool for identifying and stratifying different groups of people for societal, economic, and political purposes. Accordingly, African blood, dark skin color, and the group’s “nature” placed blacks at the lowest point of the social hierarchy. Most whites believed that these shortcomings made black Americans unable to participate successfully in a free society and that, therefore, superior and “enlightened” whites should not have to cohabitate with them. Although race is an ideology, people of the United States then understood race visually by skin color; the perceived differences were real to whites. This issue remained one of great import after the Civil War prompted nationalism, which required a clear understanding of who should and would be included in the state’s citizenry.14

The evident amalgamation of white and black people further complicated the ideology. Frederick Douglass, who vehemently denied the concept of race and instead claimed the monogenesis of humans, was incensed that Americans using scientific reasoning claimed that natural differences between the “races” prevented sexual reproduction. He was himself a product of such a union, as were numerous soldiers of USCT. Northern society grappled with miscegenation both socially and legally. In 1859 the Ohio Supreme Court upheld an 1853 law that children of three-eighths African and five-eighths white blood were not entitled to local schools if the community considered the child to be black. In an attempt to prevent further numbers of mixed-race children, and the chance that they might pass as white as adults, the state passed a law against interracial marriages “to prevent the amalgamation of the white and colored races.”15

The military became an agent to further define and entrench the social meaning of race. Similar to the American legal, judicial, and decennial census systems that divided people by color, the army recorded the complexions of each soldier. Upon mustering in, officers filled out a description roll for each recruit. In addition to age, occupation, and place of birth, the physical details recorded included the man’s height and the color of his eyes, hair, and complexion. Some of the more common descriptors used for white soldiers included fair, light, dark, red, and florid. White officers used over twenty different color variations when they recorded the skin tone of black soldiers. Overall, 20 percent of the men in the USCT had complexions of mixed race. Mustering officers used less diverse descriptions for the 27th, offering only thirteen “degrees of color,” but over one-quarter of the men in the regiment were defined as having some ratio of mixed races.16 At the same time that military service required Northern society to recognize the manhood and civic contributions of black soldiers, army policies of segregation and codifying skin tones contributed to a nationalism defined by color.

Just as the men themselves did not fit one description, the diversity of motives and causes that led them to join the 27th USCT varied immensely. In the summer of 1863, an “editorial manifesto” in the Weekly Anglo-African proclaimed that black men fought “for God, liberty and country, not money.” That September, Abraham Lincoln stated that the motives that led capable men to enlist, which included “patriotism, political bias, ambition, personal courage, love of adventure, want of employment, and convenience, or the opposites of some of these,” had already claimed “substantially all that can be obtained” voluntarily. The president’s observations applied almost exclusively to white volunteers, though, as fewer than thirty thousand black troops had enlisted at the time he defended his use of conscription. Nonetheless, men of the 27th entered service for many of these reasons and more.17

Those who encouraged blacks to fight focused on ideological reasons. Just as they had led the antebellum protests for legal and social recognition, prominent community leaders and abolitionists used their status and persuasive prose to shape national ideas and beliefs regarding African American military service. Their letters, petitions, and speeches emphasized the window of opportunity presented by the war to abolish slavery, to prove manhood, earn rights as men, and to be recognized as patriotic American citizens. These spokesmen beseeched Northern blacks to prove themselves, no matter the cost. John Mercer Langston begged, “Pay or not pay, let us volunteer.” Frederick Douglass saw the potential to produce rapid and vast political and social change when he thundered, “I mean the complete abolition of every vestige, form and modification of Slavery in every part of the United States, perfect equality for the black man in every State before the law, in the jury-box, at the ballot-box and on the battle-field.” He went on to demand the equal treatment of prisoners of war, retaliation against those who murdered captured men, and access to commissioned officer positions for black soldiers. Although Langston and Douglass undeniably stimulated Northern community action and emotion, both black and white, these men did not serve in the USCT.18 Their evocations rarely reflected individual experiences or purpose.

Soldiers who publicly shared their motivations also did so to influence Northern opinion in order to support African American enlistment. Although few newspapers published the black soldiers’ letters, those who wrote to their local weeklies or national black papers understood the public nature of their correspondence. After leaving for the battlefield with the 5th USCT, Milton M. Holland encouraged Ohio blacks to enlist in the 27th. In his February 1864 letter to an Athens newspaper, he called on the pride and manhood of those still back home to give up the comforts of civilian life and join the men already fighting for their race. Others wrote of the sacrifices they had made as a result of joining the army and exposed the inequality and struggles faced by blacks in a military system that devalued them because of the color of their skin. Their letters focused on issues of boredom, danger, fear, problems with pay, and frustration over the inability to obtain commissioned positions.19

Some men reported on recent battles, praising the achievements and bravery of the black soldiers who were often left out of the nationally circulating accounts. James H. Payne described the participation of black soldiers in the July 1864 Battle of the Crater in Petersburg, Virginia. After reassuring readers of the Christian Recorder that the men were prepared because he had held a prayer meeting before the action, he proudly shared that “our brave boys … Did they flinch or hang back? No; they went forward with undaunted bravery!” Soldiers like Payne wrote for specific purposes and to selected audiences. They used calculated prose to evoke ideals of Christian duty, martial manhood, and the right to political, civil, and legal equality. African American commentary written for public dissemination intended to provide proof that blacks in the United States deserved freedom and citizenship. Although few in number, many of these soldiers also contributed to the fight that would follow the war, one to gain recognition that would ensure African American rights not only on the battlefield but also in work, education, justice, and suffrage.20 In the end, though, most soldiers made the final decision to join the 27th USCT for their own personal causes and motivations. To blacks who joined the Ohio regiment, the American Civil War was a clash of many social, political, and economic differences, evident in the variety of reasons why men in the 27th served. These included, but were not limited to, the opportunity to collectively help end slavery, to free themselves or loved ones, and a sense of religious duty. For others, it was their obligations as men and to the Union, their personal ambitions for military service, for adventure, escape, or camaraderie. Many joined for the economic opportunities and a few because they were forced by the draft. Some of the enlistees’ reasons demonstrated noble and selfless ideals in ways fairly similar to those of white abolitionist soldiers. But for most, the motives were actually closer to the majority of reasons why white Ohioans joined the army. Unlike James Hammond, few men of the 27th USCT made an explicit reference to the federal abolition of slavery. This of course may be related to the fact that the Emancipation Proclamation had been in force for over a year by the time the regiment began training at Camp Delaware. Black Northerners understood that by 1864 the controversial war aim to end slavery had already become, even if not accepted by all, an integral part of the war.21

Men did decide to become Union soldiers because they believed it would provide the opportunity to gain freedom for specific individuals. Joining the 27th gave twenty-three-year-old Jeremiah Dickins the chance to escape slavery. The young man resided in Mason County, Kentucky, as the property of William E. Smoot, who had purchased him as a boy in 1844 when he was “about six years of age.” On February 13, 1864, Dickins ran away to join the army. Dickins went to Ripley, directly across the heavily traveled Ohio River, where he enlisted in Company D. Dickins told recruiters he was a laborer when he offered himself to the Union army, and then risked his newfound freedom by returning home to tell his mother of his actions. The motivation to liberate loved ones from bondage played an important role for other men who joined the 27th. Nineteen-year-old Andrew Jackson of Company K hoped to locate his parents and siblings, whom he believed to be living in the Walnut Hills area of eastern Virginia.22

The federal government allowed Northern states to recruit outside of their own boundaries. But Lincoln, in his attempt to appease the border states, initially kept slaves in those areas off limits to Union recruiting efforts. This did not stop the numbers of men who, like Dickins, crossed the Ohio River to enlist. Almost 21 percent of the soldiers in the 27th were born in a border state; 91 percent of them listed Kentucky as their place of birth.23

Black soldiers, maybe even more so than white men, interpreted the national conflict as “God’s warfare for man” and understood their service to be part of their religious duty. Thirty-year-old James H. Payne was a Christian soldier. He joined the regiment in February 1864, and soon after the commanding officer promoted Payne to quartermaster sergeant. He also took it upon himself to act as a regimental minister. After escaping from slavery in 1846, Payne had made his way to Ohio and by 1851 had become a member of the AME. Before the war he had been admitted to the Ohio Conference and spent his time preaching in western Pennsylvania and southwestern Ohio. Within a few weeks of arriving at Camp Delaware, he became concerned about the behavior of the men in camp and called upon the subscribers of the AME newspaper, the Christian Recorder, to send Bibles to the training camp. Between August 16, 1862, and April 29, 1865, he wrote eleven letters to the broadsheet in which he extolled his own attempts to spread the Christian message to the 27th USCT and ex-slaves as the regiment moved through the South. In addition to his self-promotional claims, some of the soldiers and white officers corroborated Payne’s extracurricular activities. They described him as a chaplain and “sort of a preacher.”24

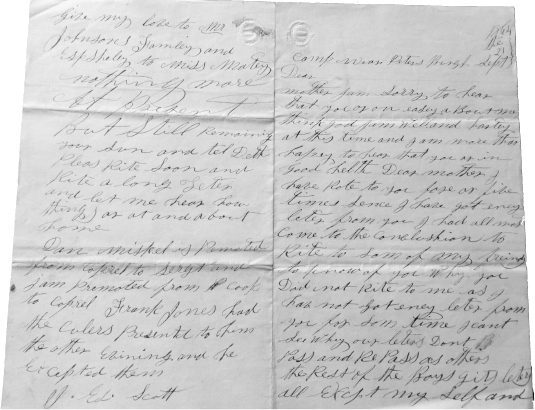

Blacks who lived in a small village just outside of Chillicothe in Ross County repeatedly sent letters sharing their prayers for their family and friends who served in the 27th. The people of Massieville put their trust in God to protect their loved ones away from home, sometimes fasting for the soldiers and their mission. After reading about their activities, Sgt. Daniel Mischal of Company H wrote to Nancy Scott, the mother of one of his comrades, that the soldiers wanted all of their prayers so that they “may restore pease to the union agane and whirp the rebels back to the union agane.” Christian duty and the preservation of the Union merged for this soldier and his community, helping to elevate the black man to a social status previously denied by most whites. This type of sacrifice did not go unnoticed. The Cincinnati Western Christian Advocate, the newspaper of the Ohio Methodist Episcopal General Conference, called on followers to “recognize the essential manhood of the negro, and his entire equality before the laws and in the sight of God.”25

Although the Ohio legislature had barred blacks from the militia since 1803, the desire for martial participation proved to be a strong motivating factor. William E. Jackson of Cleveland helped to continue a family military tradition. His father, William H., who had been a slave in New York, fought in the War of 1812 and later served in the navy. On February 25, 1865, the younger William followed in his father’s footsteps when he volunteered for Company K for a one-year term. James W. Bray, born in Logan County, Ohio, joined the 27th USCT after spending most of the previous seven years living with soldiers. From August 1857 until mid-1860, Bray was with Fitzhugh Lee and the 2nd U.S. Cavalry scouting for Comanche Indians in Texas. Bray was not a soldier but a paid servant. At about the same time that Lee became the instructor of cavalry at West Point in 1860, Bray returned to his home in Bellefontaine, where he worked as a barber. In May 1861 he again took a position serving Union army officers, first with Robert P. Kennedy in the 23rd OVI and then Cyrus W. Fisher in the 54th OVI. He remained with the 54th until November 1862. In May 1863, after Massachusetts began recruiting a second black regiment, Bray went to Camp Meigs and enlisted as a soldier in the 55th Massachusetts. After serving only a few months, officers discharged him for medical reasons. Bray returned to Ohio, and after recuperating from a hernia, enlisted in Company H of the 27th. His brother, Charley, accompanied him, not as an enlisted man but as a hired servant for Lt. James W. Shuffelton of Company H. Shuffelton previously served with Fisher in the 54th OVI. Like the Bray brothers, Shuffelton, Kennedy, and Fisher were all from Logan County.26

Adventure, confidence, and the chance to escape the restraints of family and community led many young men to enlist. The army provided black men with the opportunity to travel well beyond the localism that shaped many of their lives in Ohio, and the ability to meet new people within the safety of a community of other black men offered a sense of brotherhood previously unavailable to many of them. Zephaniah Stewart, a twenty-four-year-old private in Company G, tried to explain the experience to his wife when he told her that there were “15,000 colored men and three times that maney more white men” near his camp in Virginia. Others joined as a result of peer pressure. And soldiers who served as noncommissioned leaders of black regiments or those who proved themselves under pressure in battle gained self-esteem from their experiences. Most of the men lacked this prospect in the civilian sphere, where the socially constructed notions of black inferiority prevented such achievement. This was especially true for those individuals who had previously demonstrated evidence of uncivil behavior, such as thirty-nine-year-old Thomas Clark. The Pike County resident reportedly abused his wife and had spent time in the Ohio Penitentiary after being found guilty for assault with the intent to kill.27

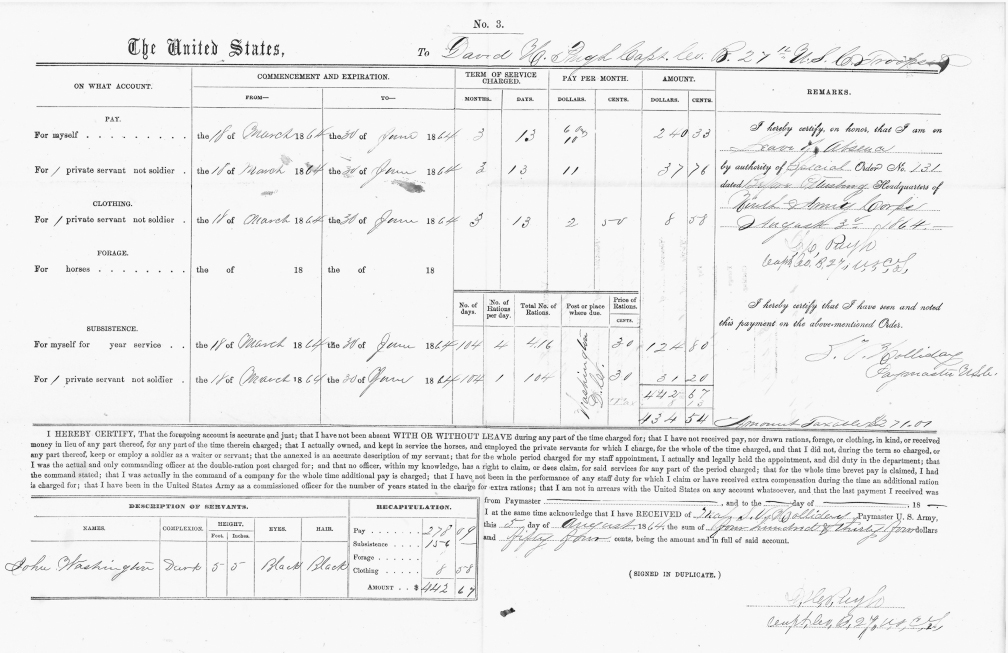

Fig. 2. This voucher for Capt. David H. Pugh in Company B of the 27th United States Colored Troops shows his pay due from March 18 to June 30, 1864. It also lists his black personal servant, John Washington, who received pay, subsistence, and a clothing allowance from the United States Army. (Author’s collection)

Others sought to expand their horizons through military service for different reasons, including one young soldier who may have been seeking freedom from parental control when he attempted to enlist in the 27th USCT. On July 28, 1864, William Scott told recruiters in Cincinnati that he was eighteen when he signed up as a two-year substitute, or “bullet proof,” for an Irishman named Henry Fitzsimmons. William’s father, Andrew, a native of North Carolina, found his son at the Columbus military barracks awaiting assignment. Scott’s independence from his parents seemed to be sanctioned by the powers of the United States Army when officials denied the parents the right to claim the newly enlisted soldier.

However, on August 9 the elder Scott and his wife Charlotte made an official statement to the justice of the peace in Bellefontaine. They swore that their son was actually sixteen years old and had been “without their knowledge and consent enticed away from their parental care and protection.” They wanted William to return home, not only because of his young age but also because he was crippled in both legs. According to congressional acts, passed on July 13, 1862, and February 24, 1864, men under the age of eighteen could not enlist without parental consent regardless of their color. After receiving the affidavit, the Adjutant General’s Office agreed with the evidence and forwarded the complaint to the secretary of war, recommending discharge by order of the governor. Ohio governor David Tod complied and on another occasion assisted the mother of a fourteen-year-old who tried to leave with the 5th USCT. William, who in any case had never received his bounty from Fitzsimmons for taking his place, must have thought his parents had also cheated him when they returned to Columbus and claimed him from the barracks.28

Many Ohio blacks, similar to some white Northern soldiers, decided that the army could provide them with a better economic status than they could find at home. Although the army did not offer the best compensation, especially during the first year of recruiting when the government paid the USCT less than it did white Union soldiers, it was better than most could expect locally. Few Ohio blacks earned the average wage of $1 to $2 per day, especially rural men who worked as farm laborers. Many received barely half of that, without any guarantee of a steady income. Furthermore, the real wages of Northern laborers could not keep pace with the inflation caused by the wartime prosperity. The mood on the home front took an ugly turn as urban unskilled white Ohioans, often immigrants, expressed their hostility. They were unhappy with their own economic plight and feared it would only get worse with the threatened arrival of ex-slaves. They took out their frustration on black workers.29

By the time Ohio began recruiting for the 27th USCT, the home-front threats by white workers led many blacks to consider the potential for economic benefits from enlistment, as Congress had begun to debate equal pay. Additionally, in spite of being denied access to commissions, black men who were promoted to the noncommissioned positions did receive additional monthly stipends. And once the government made federal bounties of $100 to $300 available to blacks, the decision to volunteer became all the more attractive. Even when daunting information reached the Northern population, including the news that Confederates would not guarantee quarter to captured black soldiers and that Union commanders used men in the USCT more for fatigue duties than fighting, blacks continued to enlist in the 27th.

The potential benefits outweighed the risks for men like Peter Howard, who was a farm laborer in Columbus before the war but traveled back and forth to Cincinnati to find work. This placed him in a tenuous position, not knowing if or when he would have an income. When Howard enlisted in February 1864, the twenty-four-year-old had for the first time some type of dependable earnings. When he arrived at Camp Delaware he was promoted to corporal, and by May 1865 he had become the sergeant major of Company C, both of which ranks came with an increase in pay. But his first promotion came before the equal pay legislation, and therefore he received not only less than noncommissioned officers in the OVI but all white privates as well.30

Early on, the army’s failure to offer equal pay became the greatest challenge to the successful enlistment of black troops. Soldiers serving in the USCT, according to the Militia Act of July 17, 1862, would receive only $10. General Orders, No. 163, added the clarification that in addition to the monthly stipend, blacks would receive one ration per day and that $3 of their pay “may be in clothing.” White soldiers received $13 per month, plus a $3.50 clothing allowance. Despite the congressional act, Ohio recruiters promised the men who enlisted in the 5th USCT that they would receive equitable compensation. Governor David Tod, who angrily challenged the federal government’s policy of unequal pay, had to break that pledge when the War Department refused to honor the state’s commitment. Black leaders, the men, and their families immediately and continually objected. In February 1864 this issue took on a dangerous immediacy when soldiers of the 3rd South Carolina Infantry protested the unequal pay. Officers ordered the men to return to their quarters, but several refused, thus disobeying direct orders. As a result, commanding officers charged Sgt. William Walter, an escaped slave, with inciting a mutiny. A committee of white officers found him guilty at his court-martial, and a firing squad shot him to death.31

Most Northern blacks were likewise unhappy with discriminatory pay, but they found less dangerous means of protest. Some refused to accept their compensation, while others wrote to bureaucrats in Washington. The federal officials remained steadfast in their belief that blacks should be paid differently than white troops. In June 1863 Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton sent a telegraph to the Ohio governor explaining that the solicitor of the War Department had examined congressional acts on military service and concluded that $10 for black soldiers was appropriate. Leaders believed that blacks would fill the back line of support, not become the primary defenders of the Union. Therefore they did not deserve the same pay. And since they would be spending most of their service doing fatigue duty, black soldiers would require their clothing replaced more often than fighting men. Instead of equal pay, the War Department offered the USCT one month pay in advance. Stanton explained that it was up to the individual states, which were receiving credit toward their draft quotas, to make up any difference in benefits. Lincoln defended the inequitable compensation, explaining that it was necessary until more white Northerners became comfortable with the idea of blacks in the military. The president sought the support and understanding of the black leadership when he assured Frederick Douglass that eventually the pay would be equal.32

By early 1864 some of the Northern white population had begun questioning the validity of the government’s unequal pay policy. The editors of the Clinton Republic questioned why black men who exposed their lives for the Union had yet to be given their “justice and beneficence.” The Cincinnati Gazette warned that blacks in the state were very displeased, and that the unequal pay had a demoralizing effect on the troops. Tod complained that the “item of pay is a most serious obstacle in my way” to raising black regiments.33

This discrimination affected the soldier’s commitment, the stability of African American families, and the recruiting efforts of the state government. Many decided not to enlist after learning that blacks could make more money by taking jobs as laborers or teamsters for the Union army, and with less risk to their safety. Similar to the first months of organized USCT recruiting in the North, blacks sought opportunities to enlist in states where political and military leaders offered better financial incentives in order to fill their own state’s quotas. In February 1864 the Scioto Gazette reported that recruiters for the 8th USCT mustered in almost fifty men in Wilmington, Delaware, and sent them to Camp William Penn in Philadelphia. Although the group was composed largely of runaway slaves, the potential of losing black Ohioans to out-of-state recruiters in a similar fashion brought the serious state of affairs to the attention of state and local leaders. Unless Tod did something soon, he would no longer be able to count on black enlistments to help keep Ohio out of the draft.34

Problems with how the government delivered compensation to the USCT also became a growing concern for black families and activists. In March 1864 a man from the 54th Massachusetts complained to the Christian Recorder that black soldiers had still not been paid after almost a year of service. To add insult to injury, the men heard that white soldiers were being paid every two months. Paymasters had an almost impossible task. Although they hoped to pay each regiment on a scheduled basis, the reality of war made it difficult and sometimes unsafe to locate many of the troops. As a result, soldiers white and black waited months or sometimes over a year to be paid. By late April some black leaders had become so aggravated that they ceased discussing why and how the situation evolved. They only wanted it corrected. They viewed both financial issues as one problem and demanded that black soldiers get full pay and those already serving should be “paid forthwith.” The Christian Recorder lambasted the injustice and claimed that the real reason these men went without pay was because of the color of their skin. The editor reminded blacks and federal governmental leaders that race did not preclude them from bravery or their desire to take care of their male responsibilities at home. In an attempt to keep USCT enlistments steady, other black leaders and sympathetic whites tried to assure potential soldiers. They maintained that, despite the lack of equal pay, at least they would earn the respect of other Americans and should therefore continue to enlist for a higher cause.35

Soldiers who fought for their country brought respect to Northern black communities, but honor could not protect their loved ones, who were left to fend for themselves. The state government in Ohio provided no financial assistance for dependents of USCT while the men served, although families created through civil marriages did have access to the July 1862 federal pension for soldiers who died of war injuries or noncombat reasons. Gov. John Brough convinced the state legislature to levy a tax to support soldiers’ families, but it provided assistance to the families of state regiments only. Therefore, the federally designated USCT and their families were legally excluded from this aid. Some local areas did provide for soldiers, regardless of race. George H. Guy wrote to his township trustees in Champaign County that “the rest of the mens wifes in my company” get some support, and he wanted to check if they would provide the same to his wife. The financial hardship could be devastating, and it affected the decision of men who wanted to enlist in the Ohio regiment, whether they were married with families or were sons who helped to care for mothers and siblings. In order to sustain black military participation, black newspapers repeatedly encouraged their readers and churches to provide the much-needed financial support. Soldiers sometimes pleaded with the white leaders who had enticed them to enlist, like when Richard Hedgepath of Company H wrote to Amos H. Vickers in Athens County that he hoped that the white merchant would “assist my wife untill i get back if i ever do get back.”36

This hardship placed black recruits in a difficult position. George H. Guy, for example, thought of himself as a “soldier in the service of his country” but was desperately worried about his family. While Guy obviously had a reason to put forth his patriotism, it was, he felt, more important that he had the right to ask for county assistance being provided to soldiers’ families, something most understood as reserved for white soldiers only. His concern was apparent in his comment that if he lived, he would repay the money if necessary. Guy dated his request from Petersburg on July 30, 1864, the same day as the disastrous mine explosion at the Battle of the Crater that killed a large number of men from his division. With his own life in jeopardy, he sought all economic benefits available to a soldier.37

The federal government moved slowly to correct the injustice. Northerners developed the argument that if the Union was willing to accept the help of African Americans, then it should compensate them for their “conduct and valor.” The Scioto Gazette editorialized that “this simple act of justice has been quite too long delayed.” In his annual report in December 1863, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton asked Congress to pass equal pay legislation. Thaddeus Stevens, an abolitionist and Republican from Pennsylvania who chaired the Ways and Means Committee, introduced the bill in the House of Representatives. Opponents delayed the action with arguments that equal pay would degrade white men, while legislators debated over who should receive equal pay and if it should be retroactive. On June 15, 1864, Congress passed the Equal Pay Act, in which the revised monthly earnings applied retroactively to January 1, 1864. In July Attorney General Edward Bates ruled that if a black soldier was free on or before April 19, 1861, and not drafted, he would receive equal pay back to the beginning of the war. Although the editor of the Christian Recorder applauded the new law, he bitterly inquired why there was still no promotion for bravery. Yet the fight for equal pay served to further organize Northern black communities, and in some cases the common goal helped to unify free and ex-slave soldiers. Although not a complete victory, the success brought hope that more change could happen for the soldiers and all people of color.38

The Scioto Gazette reported that although Congress was prepared to make the pay of black troops equal, they failed to raise bounties for the soldiers. The editor believed that this was the reason why local black enlistment had slowed to a trickle. He was concerned that, as a result, the draft could come to Scioto County. The federal government used bounties or bonuses to encourage volunteer enlistments, and by the fall of 1863 three-year recruits were receiving a one-time $300 payment. Even with this incentive, however, white Union enlistments had dwindled throughout the year because of military setbacks and the length of the war. As a result, the federal government decided that conscription would be necessary in order to meet the demand for soldiers. Congress used the Enrollment Act of 1863, which required all males ages twenty to forty-five to sign up for a national draft. Only if a state failed to meet its quota would men be drawn from the enrollment records, which Ohio was able to prevent in the first draft. Free blacks, living in counties subject to the draft, could earn $300 under the October 17, 1863, call for troops. But the following April the maximum federal bounty for all recruits, subject to draft or not, was readjusted back to the April 1861 bounty provision that provided $100 for white soldiers only.39

Ohio did not offer a state bounty, but citizens could use local bounties to meet their quota. At first Ohioans used these financial enticements as a way to help the families left behind, not as an encouragement for enlistment. Counties and townships engaged in civic competition with neighboring areas when they solicited donations to fund bounties. Authorities in the townships or counties that collected the money decided whether or not to offer it to black volunteers. When Governor Brough announced in January 1864 that Ohio had permission to raise a second USCT regiment, the Athens County Military Committee published a call for blacks to enroll for the same $100 bounty that it provided to white residents. When William Johnson and John McDonald volunteered in Lima, the provost marshal of the Fifth District, Daniel S. Brown, credited their home district in Upper Sandusky in Wyandot County on their volunteer enlistment forms. Several days later, George Gibson wrote to Brown explaining that his township, where the black recruits were born and resided, had met its quota, and requested that the two men be credited elsewhere so that they would receive a local bounty. Brown complied, and both of the soldier’s company muster-in rolls show that Wayne Township in Warren County claimed them toward the draft quota, thus allowing the men to collect a bounty.40

On March 28, 1864, the state enacted legislation that granted townships and cities the power to levy property taxes to pay $100 bounties to the men who had filled the two previous federal calls. In February 1865 Ohio passed another act to allow the same for the December 1864 call. These bonuses were designed to show appreciation to those men who volunteered in order to avoid a local draft. The state, however, could not compel a locality to comply, or to provide the bounty equally to federal USCT recruits. Most Northerners appeared to be willing to accept the black volunteer enlistments in order to avoid the draft, but in the end many failed to extend to them the benefit of collected local bounties. Although civic pride and the use of black recruits helped to keep Ohio from requiring the draft in all but a few counties in the last three calls, the men of the USCT and their families were once again denied financial equality.41

In July 1864 the federal government made a final revision to the federal bounty system. Men who volunteered for one year received $100, for two years $200, and for three years $300. That month, when Governor Brough announced that Ohio must come up with fifty thousand more men by September, he assured the black population that they would receive equal federal bounties. But some wondered if Congress would apply the edict to all soldiers. It took several months, but on November 29 the Scioto Gazette reported that the secretary of war had declared that black recruits were entitled to the same bounty as whites. This was welcome news to Robert Leech of Kentucky, who joined the regiment in August 1864, less than a year after the birth of his first child. The service provided Leech with the financial means to remove his family from a slave state when he received a $100 federal bounty for enlisting for a one-year period. He planned to move his wife, Isabella, young daughter, Mary, and widowed father, Joseph, from Lexington, Kentucky, to Xenia. Another instance involved Edmumd Coursey of Company K, who had died of pneumonia several months before Lt. William Dunkhurst wrote a letter on his behalf to an Athens County military committee member. The letter explained that Coursey had not been paid since his August 1864 enlistment and was also due $200 of his $300 bonus.42

Moses M. A. Jones of Akron may have enlisted for the $100 bounty in order to finance a house he hoped to build for his family. As a barber, the thirty-six-year-old would have heard discussions regarding how the war appeared to be coming to an end, so he waited until February 1865 to travel to Cleveland to enlist in Company D. Thirty-year-old James E. Scott of Chillicothe also saw the war as an opportunity to purchase property. Not only did he frequently send money home to his mother to hold for him, he eventually had her place a down payment on a nearby lot. He also asked her to check with local officials to see if they could change his enlistment paperwork, as he believed that he was erroneously credited to Delaware County. Volunteers from Ross County, where he and his mother lived, were paid local bounties in addition to the $100 he was due from the federal government.43

Although bounties could be used to encourage enlistment, the process sometimes led to soldiers receiving less money than they should. Scott’s enlistment paperwork was not actually an error. Unbeknownst to the men, district provost marshals often credited black recruits to townships and counties that fell short of meeting their quotas. If the local bounty was a different amount than that of the soldier’s own community, the soldier had to go with the credited township’s amount. Richard Hedgepath wrote to a member of the military committee in Athens County to apologize that he and Edmond Coursey had been credited to Wellington in Lorain County. The soldier explained that “I understand you was disatisfied not giving the township credit. he ought not think hard of me and Coursey for we done the best we could we tried to give our township credit.” Hedgepath further explained that he did not learn about the discrepancy until his officer told him after they left Ohio. While he and Coursey’s widow received federal bounties, they most likely could no longer claim the bonus from their Athens County township. Other men lost funds to brokers who claimed they would help get the maximum bounty and substitution fees. Brokers could charge as much as 66 to 75 percent of available bounty money. Numerous enlistees were cheated out of their entire bounty but did not become aware of the scam until it was too late.44

In a few cases, the soldiers lost bounty money to white officers. In December 1864 Governor John Brough received a letter from the local military committee in Washington Court House complaining that they had procured four substitutes, each of whom should receive a total of $475 in local and federal bounties. The soldiers—John Barney, Zebedee Cain, James D. Gillas, and Hezekiah Stewart—reported home to M. J. Williams that they had not received any of their money and had heard that it had been stolen. Brough’s investigation uncovered the fact that the men had left Camp Delaware with Lt. Daniel J. Miner, who had supposedly received the soldiers’ money from the officer in charge of the black training camp, Capt. Lewis McCoy. Several months earlier, Miner had requested permission to return to Ohio to retrieve his luggage, which had not accompanied the men to Virginia due to problems with the wagon train. Miner reported that he had heard that McCoy had broken into his valise and removed all of the money, and the captain begged for the opportunity to retrieve his soldiers’ money because many of their families were “suffering for want of these funds.” Command denied his request, and he was reassigned to a different company in the regiment. Although the governor asked the recently promoted commander of the 27th, Col. Albert M. Blackman, to take care of the issue, it is not clear if the soldiers received all that was promised to them. At muster-out the only recorded amount due to each of them was the $100 federal bounty for their one-year enlistment.45

Bounties also provided the opportunity for abuse by civilians. These swindlers, or bounty jumpers, signed up and took the money with no intention of serving, an activity that was most common in the urban parts of the state, especially in Cincinnati and Columbus. In December 1864 James Beverly went to Dayton to look for work. Unable to find a job, the twenty-two-year-old farm laborer enlisted into service after being promised a total of $225 in local and federal bounties. After appearing at the provost marshal’s office and being denied the money, Beverly left with the impression that he had not completed the enlistment process. The next day, upon returning to Cincinnati, a substitute broker offered him $500. Although he claimed that he made it clear that he would only sign up as a volunteer, he accompanied the broker to the local recruiting office, where he completed the paperwork and received the money. After depositing his wealth with the provost marshal, Beverly left to prepare for his journey to Tod Barracks in Columbus. Upon reaching the camp, it became clear to presiding officers that Beverly had signed up twice, once as a volunteer and then as a substitute. He was promptly arrested for bounty jumping.46

Beverly’s case was complicated due to the different names on his paperwork. Either he intentionally gave false monikers, or recruiters erred. Officers listed him as both John and James, and sometimes Everly instead of Beverly. A court-martial found Beverly guilty and sentenced him to twelve months of hard labor. Although it appeared that substitute brokers might have manipulated Beverly, he was not completely innocent. In September 1864 Beverly had received a $100 bounty when he enlisted in Columbus and was assigned to Company D of the 27th USCT, a position he had yet to fill. Beverly’s desire to obtain money from the substitute and the bounty system ended up costing him a prison term.47

Many blacks enlisted as substitutes. For the first two drafts, the federal government allowed men to pay a $300 commutation fee to avoid enlistment, but this was outlawed for the last two drafts. As a result, the price of substitutes skyrocketed during the last months of the war, leading to a growing number of new recruits. Men could receive $300 to $500 in Cleveland, where 93 percent of the draftees paid for someone to replace them. The number of black substitutes grew even more after changes to the Enrollment Act allowed them to serve in place of white men. Substitutes counted for over 26 percent of the 6th USCT, a regiment formed in Pennsylvania. Just over 16 percent of the 27th USCT regiment joined because they were paid to replace someone else. When twenty-five-year-old Dock Leech could not obtain his pay for recruiting black troops in Kentucky, he took advantage of the increased compensation and served as a three-year substitute for John Fay of Cincinnati. The hard-working Leech was soon promoted to corporal of Company H. Another soldier, nineteen-year-old Jeremiah Stewart, requested officers at Camp Delaware to document that he had received $350 when he agreed to be a substitute in July 1864. The Tennessee-born private wanted to ensure that he would be paid the $250 taken from him and placed on deposit until the end of the war.48

The system often proved fraudulent, though, sometimes by the man seeking replacement and at other times by the substitute. Brokers also took advantage of the situation. On September 7, 1864, the Daily Ohio Statesman observed that “the bounty and substitute brokers have been and are still driving a thriving business in their peculiar vocation.” The Cincinnati Gazette reported that the Office of the Provost Marshal had exposed a broker who had cheated several black substitutes. One man had been promised $300 but only received $27, and the broker ended up with $448. The broker offered another soldier $200 but only gave him $100. The provost marshal announced that he would go after the broker and would cancel the contracts if the men were not paid.49

William Joseph Nelson suffered a similar fate when a man claiming to be a recruiter came to his home in Mercer County and offered the twenty-three-year-old a $200 bounty for one year’s service. Nelson had recently married a widow with eight children and desperately needed extra money. When the new recruit arrived at Camp Delaware, he learned that his enlistment papers stated he was a three-year substitute. After conferring with other soldiers, who convinced Nelson that he had been unjustly enlisted, Nelson took part of his money and left for home, but in late January 1865 he was arrested as a substitute deserter. While awaiting trial, Nelson wrote to Governor Brough and explained his circumstances. He expressed a desire to serve his “country in an honorable way but not as a slave.” Brough ordered an investigation, which concluded with a report from Maj. John Skiles, commanding officer at the Headquarters for the Draft Rendezvous in Columbus. Skiles stated that Nelson was brought in as a substitute deserter, but after the recruit acknowledged that he had left his post, he was released and forwarded to the 27th USCT on February 13. But on his way to Virginia, Nelson was once again detained and on February 15 was sent to Baltimore under guard. This time he wrote to President Lincoln, explaining his plight in more detail. The man who had offered Nelson the $200 bounty later caused Nelson to get drunk and sold the inebriated man to a substitute broker. Nelson argued that even though the recruiter correctly marked him as a substitute, Nelson himself had no knowledge of the transaction. Although it is unclear exactly what happened to Nelson after this, he never joined the regiment and he is not listed on any of the muster rolls.50

Some black men served in the 27th USCT because they were drafted. In the early years of the conflict, the War Department left recruiting to the states. When the number of volunteers continued to drop in 1863, the Union resorted to the draft. The federal government ordered each state to provide a quota of soldiers. The total number was then divided between the state’s congressional districts. According to the Enrollment Act of March 3, 1863, if a state failed to raise the assigned number of recruits through volunteers, a draft would be imposed on the districts that fell short of their quotas. The first national draft for the United States called upon all male citizens between the ages of twenty-five and forty. If drafted, the men had the option of providing substitutes or paying a $300 commutation fee that would be used to fund federal bounties. Men could also be excluded due to a physical disability. The War Department interpreted this legislation to include blacks, although Ohioans initially did not. Reaction nationwide varied, but the most violent response occurred in New York City. A protest against the draft turned into a deadly four-day riot that targeted blacks. Poor whites, angry that they could not afford to pay the commutation fees, turned on those whom they blamed for the situation. Already distressed by the economic competition with blacks, the white New Yorkers had no intention of dying in a war that had evolved into one for emancipation.51

For many Northerners during the first two years of the war, community pride was at stake. The compulsion to serve appeared unpatriotic. Some believed that the commutation clause was unjust, and others concluded that paying for substitutes was cowardly. Yet the inability to gain the necessary numbers of white men, coupled with the prospect of a draft, became one of the strongest motivations in Ohio for the acceptance of blacks in the military. Other than in a few areas where a significant number of antiwar Democrats resided, Ohioans began to encourage the use of black troops. Republican supporters, asserting their patriotism, proclaimed that “no one, as a general rule, but traitors are objecting to the drafting of negroes.”52

This was put to the test as Ohioans dealt with the national draft. Of the 245,000 Ohioans who served the Union, 8,750 were forced by conscription. Although the state avoided it in October 1863, several of state’s nineteen congressional districts faced the prospect during the next three calls for men. On February 1, 1864, the federal government required Ohio to supply 51,465 men and then on March 14 requested an additional 20,598. In July Governor Brough reported that the president required 50,000 more Ohioans. Some districts focused more on the filling of positions instead of locating men who would be quality soldiers. This led to an increase in the number of bounty jumpers and deserters, especially when communities used bounties and local brokers to fill their quotas. After the Enrollment Act of February 24, which specifically included all able-bodied African American males ages twenty to forty-five, free and slave, African Americans became legally bound to register for the draft. Both the 5th and 27th still needed more men, so Brough reminded blacks that they would receive equal pay and bounties if they volunteered. Furthermore, the governor indicated that he might start a third black regiment if enough men came forward.53

The number of men drafted who served in the 27th USCT, just over 3.5 percent, correlates with Ohio’s overall conscription statistics. The major difference was that few of these men could afford a substitute. Many of the drafted black men came to the army with a very different attitude than did volunteers, especially the willing enlistees who received bounties. But being a conscript did not necessarily preclude a man from taking advantage of his position. Soon after joining the regiment, Champion Bowman of Marietta became first sergeant of Company I, which elevated the pay and status of the twenty-two-year-old tobacconist. And ironically, the national draft may have been the most significant factor that led to the acceptance of black military participation. For many, African American inclusion provided evidence that black men were needed if the Union was to succeed, and therefore conscription was interpreted in a way as a “badge of citizenship.”54

For those who voluntarily enlisted, for “patriotism, political bias, ambition, personal courage, love of adventure, want of employment, and convenience, or the opposites of some of these,” the reasons proved to be in some ways like white Ohioans’ motives.55 Most of the men arrived at Camp Delaware optimistic about becoming a United States soldier. Although they had made the decision to join individually for their own cause, they soon became part of something much larger. The men brought more to the war effort than simply providing the back lines for white Northern troops. Joining the Union army placed them in a role where they would collectively have more power to challenge the American social hierarchy than most of them had ever anticipated.

Recruiting for the 27th USCT began in late December 1863. Twenty-year-old Isaac Stillgess lived with his parents in Champaign County when he volunteered to serve in the Union army. He was attending school along with four younger siblings when the news of war reached their Urbana Township farm. Abraham C. Deuel, provost marshal of the Fourth District, swore in the Ohio-born soldier for a three-year period. Deuel had a busy holiday season. On Christmas Day he signed at least three men from Logan County. Eaton Banks, a single nineteen-year-old born in the county; thirty-eight-year-old Exum Wade, a native of North Carolina who made his home with his spouse in Monroe Township; and Richard James, aged forty-two, who lived with his wife and eight children in Bellefontaine, all joined the 27th. The next day, one of Stillgess’s neighbors, twenty-five-year-old Calvin Gales, enlisted. The day laborer lived on John Collins’s farm with the New York emigrant’s family and two other boarders. Three days later, twenty-two-year-old farm laborer Watson T. Artis signed with Deuel. Born in North Carolina, Artis lived in Pickeraltown with his wife, MaryAnn.56

Meanwhile, in the northeastern part of the state abolitionist Storrs S. Calkins of Oberlin recruited men from the Fourteenth District. On January 8 twenty-eight-year-old Perry Carter enlisted. The Kentucky-born laborer lived in Oberlin with his wife and two sons. Isaac Noble, a twenty-two-year-old native of Virginia, lived with his wife and infant daughter in Norwalk when he volunteered for a three-year stint in the army. And while Calkins happily accepted the recruit, he credited him to Russia Township. All of these new enlistees, along with several dozen other men who arrived at Camp Delaware in January 1864, mustered into service and became the first soldiers of the 27th USCT regiment. Together with their families and communities, these black Ohioans, free men before the start of the war, would gain and lose, would celebrate and suffer, as their service in the Union army changed their lives forever.57

The War Department had not yet granted official permission to Ohio to begin recruiting a second black regiment when Deuel and Calkins accepted the men. But state officials knew from Governor Tod’s earlier correspondence with Secretary Edwin M. Stanton that federal approval would most likely be forthcoming. Ohioans also realized the importance of maintaining the recruiting momentum in the black communities. Deuel, along with the other officers of the Provost Marshal General’s Bureau in Ohio, had faced considerable opposition in their fall 1863 campaign to keep the state out of the draft. Ohio’s African American population was needed more now than ever to help prevent the embarrassment of conscription and to help end the war.58

By the time the War Department sent official approval to the new governor to raise a second black regiment, the number of potential recruits had been severely tapped. Thousands of Ohio blacks had already enlisted in the 5th USCT, 54th and 55th Massachusetts, and several other regiments from Northern states. Governor John Brough, a prowar Democrat turned Union Party man, faced a serious challenge when he assumed the responsibility of filling the regiment after he took office in January 1864. The earlier warnings spread by antiwar Democrats that thousands of ex-slaves would seek refuge in Ohio as a result of the war proved to be false. A special census, with fifty-seven of eighty-eight counties reporting by April 1863, revealed that only 1,251 blacks from slave states had arrived since the outbreak of hostilities. Neither border state runaways nor contraband seemed to be as interested in the state as Ohioans had feared.59

In late 1863 the leaders of the federal and Kentucky governments wrangled over the issue of drafting slaves, a result of which was a compromise with the federal government that allowed masters loyal to the Union to keep any bounties if they sent their slaves to serve for Kentucky. This meant that those bonded Kentuckians who wanted to make the choice to fight and keep the bounty for themselves headed to Tennessee or Ohio. But the editor of the Columbus Crisis admitted that in early 1864 fewer freedmen had entered the state than expected. Officials could not count on gaining large numbers of recruits from nonresidential blacks. Therefore, to be successful Ohioans would need to continue all efforts to fill the ranks of a new regiment. On January 16, the same day Stillgess and his comrades arrived for duty at Camp Delaware, Governor Brough informed the officers of the Provost Marshal General’s Bureau that all the black recruits were to be assigned to the newly created regiment.60

Fortunately for the state and the black community, white support for the USCT had increased by late 1863. Some Northerners even embraced the idea that African Americans had the ability to succeed in combat. Newspapers printed reports and letters of white officers and soldiers who had witnessed the bravery and tenacity of black soldiers in battle. Ohioans were with Gen. Stephen A. Hurlburt, commanding officer of the XVI Army Corps in Memphis, Tennessee, along with several black regiments. Hurlburt, originally from South Carolina, declared that the soldiers had “demonstrated the fact that colored troops properly disciplined and commanded can and will fight well.” The editor of the Xenia Sentinel summarized the changing attitudes in Ohio when he wrote that “it has come to be an established fact in the history of this war that colored soldiers will fight.” Local newspapers acknowledged that Ohio blacks were doing “some excellent work,” especially the “boys” from Ross County.61

Newspapers also reported on the increasing number of enlistments of African American troops nationally. In December 1863 editors of the Delaware Gazette printed a story on the recruitment of Missouri blacks. The federal government had authorized the enlistment of ex-slaves and contrabands there in order to spare whites from the draft. As the army moved through the state, the number of recruits increased daily. The secretary of war endorsed the plan to use the runaway men, stating that the “freed slaves make good soldiers, are easily disciplined, and are full of courage.” By the end of December more than 50,000 blacks were serving as soldiers, and over 106,000 were in government employment. The editor of the Clinton Republic pointed out that these men filled positions that would have otherwise required a white enlistee. The writer sarcastically pondered why “a great many men to the North who from anxiety for the safety or comfort of the negroes, or for some other reason, are bitterly opposed to the enlistment of negroes.” Yet despite the overall support of the federal government’s new military strategy to use blacks in an effort to end the ongoing conflict, there still existed some resistance to raising black troops.62

In 1863 and into early 1864, the opposition to USCT recruitment in Ohio tended to be politically motivated. Democrats, especially the “peace” faction of the party led by Copperhead Clement Vallandigham, played on nineteenth-century racial beliefs of white superiority. After their November 1863 defeat at the polls, they increasingly referred to their opposition as the “black party” in an attempt to take votes from Republicans. Democrats warned Ohio citizens that arming black men was only the first step and that Republicans would eventually seek equal civil and political rights for African Americans. Edward A. Bratton, a well-to-do attorney from Vinton County, doubtless spoke for many in his community when he opined that the enlistment of USCT was an insult to white citizens. A black soldier in Zanesville faced this hostile attitude when, in February 1864, some white men tried to stop him from recruiting local blacks who had congregated in a barbershop. With the help of law enforcement, the soldier escaped the onslaught of stones thrown by an angry crowd of Copperheads.63

Many Ohioans though, for their own reasons, thought differently. In Chillicothe the editor of the Scioto Gazette chided the Copperheads by reminding them that a black man’s name carried the same weight as a white enlistee in the adjutant general’s count of the state’s quota. The editor took pleasure in telling the story of a Springfield “butternut” who planned to convince African Americans to enlist in his township so that whites there could avoid the draft. Not to be tricked, the black men returned to Scioto County and enlisted there. The Union Party supporters had achieved a double victory, boosting their own district’s volunteer numbers while at the same time humiliating their political opposition. The issue of course was much more serious. After reporting that recruitment for the 27th USCT had commenced, the editor dared Democrats to push the constitutionality of avoiding the draft by claiming that the federal government had misused its authority by allowing blacks to serve in the United States Army.64 Although the support for black troops by the white Ohio population tended to be selfishly motivated, it was vital nonetheless.

There was no division in the Southern response to Abraham Lincoln’s decision to arm blacks. Americans everywhere watched for the administration’s reaction to the Confederate threat against any that should “be sent to field, and be put in battle, none will be taken prisoners—our troops understand what to do in such cases.” Less volatile, but immediately more threatening, was the lack of assurance that they would be treated fairly by their own government. Although Congress debated the pay issue in February and March, and even though blacks had so far proven themselves, the federal government refused to place equal value on their patriotism, labor, and lives. Ohio was still offering less pay and gave no local bounties to black males who enlisted in the 27th USCT during the winter and early spring of 1864. Yet neither predicament could halt the resolve of African Americans. Despite the inequities, many blacks continued to enlist. They dared not risk being seen as unpatriotic or disloyal, as that could prevent the Northern black community from achieving crucial goals. While they hoped that the pay difference would be only a temporary distraction, some believed that the opportunity to demonstrate that blacks deserved equal political and civil rights was worth more than the $3 a month. By February 1864, over three hundred men had enlisted and were at Camp Delaware, with additional recruits arriving daily.65 Regardless of the mounting challenges, most Ohio blacks supported the formation of the 27th USCT.

Although the national government did not have an official policy for how states raised volunteer regiments, the USCT were federal troops. Therefore War Department officials controlled the system used to recruit black soldiers. At times the methods by which the rules and guidelines were implemented depended on where and who raised the regiments, making the process somewhat disorganized. Massachusetts governor John A. Andrew, who organized one of the first black Northern regiments, created a system whereby salaried agents worked with local recruiters in several states. These subagents were paid a fee for each recruit that enlisted in the 54th and then the 55th Massachusetts. In June 1863 George L. Stearns presented the procedure to the War Department. Officials approved the plan and awarded Stearns a recruiting commission as major for the U.S. Bureau of Colored Troops, which operated within the Adjutant General’s Office. Ohioans used this system when the state began filling the new regiment. Because the War Department had the ultimate authority over the process, once a state received permission to raise a federally designated unit the governor had to report all activity to the bureau. States did have some say in the process, however. Governors could select specific men to lead their state’s recruits from the bureau’s list of approved white USCT officers, and the states could also apply the total number of black enlistees to their state’s share of national troop quotas. In return, the federal government required that recruiters be paid $2 per enlistee plus expenses, although it was up to the individual states to find the resources for payment. In Ohio the funds had run short by 1864.66