On April 20, 1864, Baltimore residents welcomed several newly formed regiments of black soldiers, including six companies of Ohio’s 27th United States Colored Troops. A cheering crowd offered refreshments to the men who were on their way to join the IX Corps in Annapolis, Maryland. The atmosphere that afternoon was in sharp contrast to the events three years earlier. Citizens, overwhelmingly sympathetic to the Southern cause after the unsettling events at Fort Sumter, had poured out their wrath on the white Union soldiers sent to defend the capital. On April 19, 1861, a riot had left sixteen people dead, and over the next three weeks, secessionists destroyed Baltimore’s communication and transportation lines in an attempt to prevent any further Union access to their city. When the quartermaster of the 27th, Nicholas A. Gray, reflected upon the anniversary of the violence, he concluded that based on the treatment toward his regiment at least, some of his fellow Americans had accepted black soldiers. Not all had, though. On April 19, 1864, Pittsburgh hecklers threw stones at the men of Company G of the 27th USCT as they traveled by train through the Keystone State en route to join the regiment. Meanwhile, Companies A–F boarded the steamships Starr and Cecil for Annapolis. The men continued their journey, resolute despite the attack on their fellow troops and the horrible news they had heard earlier about the treatment of black soldiers captured by Confederates at Fort Pillow. Both the excitement of being recognized as United States soldiers and the realities of combat shaped the experience of entering wartime service. The future held prospects both uplifting and disturbing for members of the 27th USCT.1

The men under the command of William G. Neilson waited in Annapolis. The army had recently promoted the Ross County lawyer from his position as first lieutenant of the 88th OVI to major of the 27th USCT. Neilson took temporary charge of the soldiers when they left Camp Delaware, while their senior commanding officer, Lt. Col. Albert M. Blackman, remained in Ohio to complete the recruiting necessary to fill the regiment. After two days, Major Neilson and his men received their first orders. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant called on the IX Corps, acting in support of the Army of the Potomac, to relieve the V Corps from guard duty along the road between the Rappahannock River and Bull Run Creek. The soldiers joined four other black regiments, and at 11:00 A.M. on Saturday, April 23, they left on a ten-hour, twelve-mile march. That evening, as Company G boarded a steamer to Annapolis, the rest of the 27th set down their packs for the night. The exhausted soldiers had completed their first official day as part of the Union army.2

Grant had recently moved his field quarters near Gen. George B. Meade’s Army of the Potomac in order to supervise the Overland Campaign operating in the Virginia theater. His objective was to destroy the Army of Northern Virginia, so Grant instructed his officers to engage Gen. Robert E. Lee’s men at every opportunity over the next two months. As the commanding leader of all Union troops, Grant planned a massive two-part assault on the Confederacy, sending Gen. William T. Sherman to attack Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s men in Georgia and ordering Meade to capture Richmond. Grant’s decision to remain with the Army of the Potomac caused Meade a great deal of apprehension. But it allowed Grant to oversee the operations of Meade’s troops and Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James, brought in to support the movement. Honoring Abraham Lincoln’s decision to employ black soldiers against the enemy, Grant included the USCT in his plans.3

Grant’s decision to use black troops did not come from a personal agenda related to any political support or abolitionist sentiment; he simply understood his duty to obey the commander in chief. He also believed that the Union would benefit from the backline support that would free more white soldiers for the battlefield. This was not the case for Benjamin F. Butler, a Democrat whom the War Department had appointed more for political reasons than for military talents. Most of the blacks in the spring campaign of 1864 to take Richmond served in his XVIII Corps, consisting of seven infantry regiments, two cavalry units, and one heavy artillery battery of USCT. Before the war, Butler had believed that his role as a lawyer and as a representative of the people of Massachusetts required his support for the lower classes, especially immigrants. As a commander in the Civil War, he expanded his commitment to include fighting for the use and recognition of black troops. Butler therefore proved to be one of the staunchest supporters of the USCT. As a result, the soldiers in his Army of the James participated in more military engagements than most other blacks serving for the Union.4

Unlike Grant and Butler, Meade remained unconvinced about the potential value of the USCT. On April 13 he placed the black soldiers in his army, including the 27th, under the authority of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside. Grant had recently recalled Burnside from recruiting duty in New York to command the IX Corps as an auxiliary to the Army of the Potomac. Meade did not have a high opinion of Burnside or his abilities, which led to an obvious lack of support for the IX Corps, and especially the use of the black troops, in the Army of the Potomac. Instead of military action, Meade assigned the men to a disproportionate amount of fatigue and guard duty during the spring and summer of 1864. As a result Burnside, who had little power despite actually having a higher rank, refused to communicate with Meade and instead corresponded directly with Grant. Due to professional jealousies and racially motivated discrimination, the somewhat isolated nature of the IX Corps became even more so for the black soldiers. On April 19, Burnside restructured his command into four divisions. He separated the USCT regiments from his white charges, creating the all-black 4th Division under Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero.5

Ferrero had both battle and leadership experience. The son of Italian immigrants, he entered service as a lieutenant colonel of the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry. Before the war, he taught dance to U.S. Military Academy cadets, making him a favorite among the men. Late in 1861 he raised his own regiment, the 51st New York, also known as “Shepard Rifles.” After Army officials rewarded his bravery at Antietam with a promotion to brigadier general, Ferrero fought at Second Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Vicksburg. He was with the IX Corps when Grant recalled the troops from Knoxville in March 1864 to support Meade’s assault on Richmond. After three years of fighting, his superiors seemed to have provided Ferrero a reprieve from battle when they assigned him to the all-black division. Unlike the soldiers under Butler’s charge, it appeared fairly evident that the status of the USCT within Meade’s army offered little potential for anything more than support assignments in the back lines.6

The soldiers of the 4th Division, unaware of the bickering within the chain of command, followed the orders dealt to them. Traveling to their destination proved to be a trying experience for the 27th USCT. On their second day of marching, they covered eighteen miles before bivouacking at 9:00 P.M. on Sunday. They were tired and quickly grew disenchanted. Breaking the Sabbath had upset some of the men, and others expressed displeasure about the insufficient and unpalatable rations they received. Although they had been proud to put on the uniform of the Union army, wearing the new trousers, shirt, stockings, cap, coat, drawers, belt with cartridges, and stiff boots proved uncomfortable. Furthermore, they had to carry a gun sling, their Enfield rifles with bayonet and scabbard, and a knapsack filled with extra clothing and equipment. Worst of all, it rained much of the day, and that night the men slept upon the cold wet ground. But the inexperienced soldiers endured the pain and discomfort of sore feet and aching muscles from the seemingly incessant walking.7

Adding to their difficulties, the soldiers had to carry the regimental ammunition as they walked along the winding, hilly, and uneven roads, which were wet and slippery. The conditions led Charles W. Long of Company B to slip, causing him immediate pain in his right groin. That night the private from Oberlin sought treatment, and the doctor diagnosed Long’s injury as an inguinal hernia. Sgt. Charles Woodson of Company C became ill with typhoid pneumonia. Capt. Edwin C. Latimer reported Woodson’s illness to his superiors, who sent the Jackson County native to Depot Field Hospital in City Point located at the juncture of the James and Appomattox Rivers. It was no wonder that the excitement of their role in the Union’s attempt to put down the Southern rebellion quickly became an exhausting and painful introduction into the realities of soldiering and nineteenth-century warfare.8

The next day the members of the 27th continued their southward journey. The free black men felt anxious about their impending arrival in the rebellious slave state. Then, during the afternoon of April 25, the five regiments of USCT marched with Ambrose E. Burnside’s IX Corps through their nation’s capital. Some of the men stopped to wipe the mud from their clothing and boots, proud of their opportunity to participate in this once-in-a-lifetime event. Lincoln and Burnside, standing in the Willard Hotel balcony, watched as the black soldiers made their way through Washington, D.C. It was the first time Lincoln had witnessed a USCT formation. The presence of black men in uniform brought out various reactions from the crowd. Some local citizens yelled “remember Fort Pillow” and waved flags at the troops. Walt Whitman, the controversial American poet who moved to the capital and worked as a government clerk during the war, recognized the significance of the festivities when the president removed his hat in honor of the black soldiers. Somewhat disapprovingly, Whitman wondered what changes the experiment of using African Americans to help win the war might bring to the nation. For the men in Company G who entered the city the next day, the reception proved less welcoming when District of Columbia’s “Secesh white” spat on them as they marched through on their way to catch up to the regiment. But the significance of their participation was clear to the black Ohioans. Pvt. Zephaniah Stewart wrote to his wife that between Camp Delaware and the “sitty wher our president is,” he had “seen more than I ever seen in my life before.”9

The black brigades continued to face new experiences when they arrived in Alexandria, Virginia. Sgt. John C. Brock of the 43rd USCT described, to readers of the Christian Recorder, the reaction of local white residents. The Southerners were horrified to have their homeland “polluted by the footsteps of colored Union soldiers.” Brock and his comrades received a much different reception from the bondsmen. Slaves viewed it as a glorious experience when they witnessed the free African Americans in uniform, marching “with martial tread across the sacred soil.”10

The soldiers in the 27th quickly recognized the dissimilarities between the South and their Northern communities. They observed how the landscape had been devastated by the war and the dire economic conditions faced by both black and white Southerners. Many of the men in the Ohio regiment saw for the first time the effects of human bondage. While slaveholders had moved most of their chattel southward out of the reach of the Union armies, those slaves still in the area greeted the black troops with cries of joy. White Southerners, on the other hand, glared at the black regiments with disrespect and revulsion as they watched their “property” gather the few belongings they had and follow the army toward freedom. If any of the men doubted their decision to enlist, the experience of marching to Fairfax Court House provided a reaffirmation that they were involved in something very important.11 In large part, the future of their enslaved brethren and their divided country depended upon the success of the USCT.

After a short respite, the black contingency broke camp at 10:00 A.M. and headed for Manassas Junction. They marched twelve miles that day, crossing Bull Run Creek. Heavy spring rains had swollen the stream, so after rolling up their pants in an effort to remain dry, the men yelled out in surprise at the coldness and depth of the water. After the initial shock wore off, their wet clothing made their journey even more uncomfortable as they trudged toward their next encampment. Despite being the last of IX Corps to arrive that night, the 4th Division located a pleasant grove with dry ground to make its camp. Then, having reached its destination, the 27th spent the next six days guarding Union supplies on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad from Bull Run to the Rappahannock River. As the spring weather grew comfortably warmer with each day, on April 29 acting commander Maj. William G. Neilson became sick with a fever, leaving the regiment from Ohio with no field officers. Ferrero temporarily placed the thirty-four-year-old captain of Company A, John Cartwright, in charge. It would not be the last time the loss of leadership would plague the 27th. Meanwhile that same day, Company G joined the regiment just in time to take part in Grant’s campaign against Richmond.12

Despite the initial relief felt by the soldiers after they arrived at Manassas Junction, the men found few comforts available to them. The Union army had trouble providing enough food for the troops and the black regiments suffered the most from this predicament. Their overall lower economic status as civilians meant that many of the men may have been used to subsisting on less nourishment. But the constant marching since their departure from Annapolis had left them exhausted, weak, and famished, and the soldiers’ poor state of health was exacerbated by digestive problems caused by the abrupt shift from the abundance of rich foods, such as the eggs, oysters, and whiskey supplied in Baltimore to the diet of hardtack. The lack of clean water combined with the unsanitary conditions of camp caused the men to suffer terribly from diarrhea. For those who had not been able to recover from similar conditions at Camp Delaware, the difficulty became even worse. It proved fatal for John Cooley, a private in Company D, who died on May 5 at L’Overture Hospital in Alexandria, a facility for blacks opened by the Union army in February 1864. The hospital staff also tended to the needs of liberated slaves, who congregated in a contraband camp on the grounds next to the hospital. Workers soon added the Freedmen’s Cemetery to the compound, where the Virginia-born Cooley found his final resting place. He was the first black soldier buried there.13

Regardless of the increasing number of soldiers reported sick each day, the 27th continued to serve as back-line support for the IX Corps. Although they had some opportunities to practice target shooting, they spent most of their time protecting Union supplies and serving on picket and fatigue duties. Not all of the men in the Ohio regiment remained with their comrades: the 27th USCT commanders issued special orders to some of the men. Charles E. Taylor of Company A, for example, performed daily as the regimental fifer, and division headquarters issued reassignments to a number of soldiers stationed in Virginia. Superiors ordered these men to report for detached duty to serve in a variety of capacities. Thomas Gladdish of Company E reported to the quartermaster’s department for blacksmith duty on May 2, and the next day Richard Redman of the same company reported to work as a butcher for the 2nd Brigade. Throughout the war, soldiers from different companies received assignments to serve as cattle guards, teamsters, and provost guards, and as orderlies in the regimental and corps hospitals. Capt. Alfred W. Pinney and Lt. Archibald J. Sampson commanded soldiers from the 27th and 23rd USCT on a detached assignment with Maj. Gen. Silas Casey’s Provisional Brigade in the Department of Washington. As a result of the various assignments, some of the recruits spent part or most of their service removed from the regiment.14

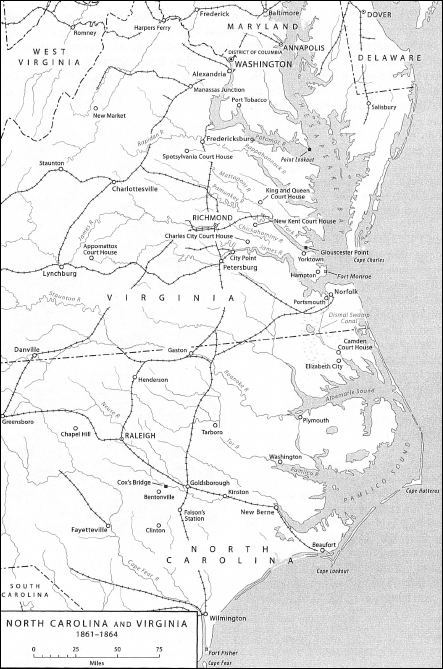

Fig. 7. The 27th United States Colored Troops served in the Union army from April 1864 to September 1865 in Virginia and North Carolina. (From Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867 by William A. Dobak. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2011)

Those who remained were sometimes affected by the absence of those who served elsewhere. An officer from Company D of the 22nd USCT stationed near Chaffin’s Farm complained that with nineteen men “on detached service around the brigade and division Headquarters” that “the duties are proportionately increased on those who are undetached or with the company.” He thought that the practice threatened the discipline and efficiency of his company, and that it deprived him “of any discretionary voice in the selection of the men sent.” The 27th shared similar experiences, caused by detached duty, illness, or injuries. On May 4 Major Neilson went to the hospital in Alexandria, where he remained ill until July. Instead of returning to lead the 27th after he recovered, he went to Elmira Prison on detached service. When ordered to return to the regiment on January 14, 1865, he resigned from service. Unfortunately, Neilson’s absence that spring was just the first in a series of problems related to procuring and keeping officers.15

There were others also separated from the regiment, but due to much different circumstances. This was the case for Levi Beer, Allen Bobson, John Horton, Benjamin McCoglin, and Preston Mosby, who all went missing during the march from Manassas Junction to the Rapidan River. On May 4 George B. Meade sent word that the black regiments were to join the Army of the Potomac. After guarding the railroad between Manassas and the Rappahannock Station for several days, the 27th USCT once again prepared to march with the IX Corps. Meanwhile, Edward Ferrero divided the 4th Division of black troops into two brigades. He placed the 27th in the 1st Brigade under Col. Joshua K. Siegfried, a Schuylkill County native who had been promoted from his position as commander of the 48th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the IX Corps.16

That evening the 4th Division broke camp and began another series of unbearable marches. Burnside detached the 4th Division to follow behind the IX Corps. There, the 27th and the other black regiments protected the army’s four thousand supply wagons and a herd of cattle that was large enough to fill a one-mile diameter valley. Grant and Meade forcefully pushed the army toward Richmond as they prepared to engage Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia near Wilderness Tavern. Supplied with three days’ rations, the 27th marched over bad roads until 2:00 A.M. and then bivouacked at Catlett’s Station under a foreboding sky. The following day they left at 8:00 A.M., and after marching for six hours, they forded the Rappahannock River. The division made camp at 6:00 P.M. On May 5, after covering thirty miles in only twenty-four hours, Ferrero told his superiors that they could go no further.17

The next morning, officers noticed that the five soldiers were absent. Capt. Edwin C. Latimer reported that Benjamin McCoglin had deserted. Fielding and John McCoglin, also in Company C, wondered what could have happened to their older brother. Few of the men from the Ohio regiment considered desertion an option, despite the growing unhappiness among the soldiers over issues of unequal pay and their uncomfortable living conditions. The unmanly act of running away embarrassed many of them. It also troubled black leaders at home who were working hard for political and social change. But McCoglin and the other men were nowhere to be found, so officers for Beer, Bobson, and Mosby listed them as deserters as well. It appears that they may have accompanied John Horton, of Company C, who needed medical attention. He was admitted to L’Overture Hospital on May 7, but the other soldiers failed to return. The officers of Company B heard an erroneous report that enemy pickets had killed Levi Beer, but no word came about the others.18

At 3:30 A.M. the roar of cannon woke the exhausted soldiers. Ferrero had planned to wait until daybreak before moving his men, as he wanted to give the troops a chance to rest. Although detached from the corps to protect the supply wagons, orders from the IX Corps headquarters directed otherwise. At 4:00 A.M. the men proceeded with due speed to Germania Ford, finding that the beauty of the Virginia countryside provided a stark contrast to the horrors of battle that raged on at the Wilderness. Late that evening the 4th Division crossed the Rapidan on platoon bridges at Germania Ford. They made camp on the southern bank of the river, relieving the men in the VI Corps, who had been guarding the bridge. The soldiers did not get a chance to rest.19

After two days of fighting, the contest at the Wilderness ended in a draw. Grant surprised Northerners when he refused to retreat, and on the evening of May 7 he ordered Meade to move the Army of the Potomac southward in pursuit of Lee. Although the 4th Division continued to follow as guards, they still found themselves in a dangerous position, and tensions increased when at 8:30 P.M. Grant sent word to Ferrero that the 4th Division might soon encounter a large number of Confederate troops. Rumors of an impending attack by rebel cavalry traveled quickly among the men, and an hour later Ferrero received orders to move his troops and all the supply wagons toward Chancellorsville before Lee’s forces could attack. By 11:00 P.M. the 27th had taken to the road again, moving with the division along Germania Plank Road as fighting continued in the distance.20

The troops arrived in Chancellorsville at 1:30 A.M. on Sunday morning. There the men encamped to the sounds of yet another battle as Lee’s army continued to engage the Union troops moving toward Spotsylvania. The light at daybreak exposed human bones protruding from the ground where a battle had been fought only a year before, and as the day warmed into a hot afternoon, the stench of putrefied, unburied bodies from the recent engagement tainted the otherwise warm spring day. The only positive aspect of the day’s macabre atmosphere came later that afternoon, as cheers to the news of a Union victory spread throughout the camp. Although the rumors later proved false, it helped the men persevere under difficult conditions.21

The 27th remained with the 4th Division near Chancellorsville as Meade’s army moved toward Spotsylvania Court House. For the next week Ferrero’s men served as the right flank guarding supply wagons along the Fredericksburg Plank Road, the unbearable odors of decaying human corpses permeating their camp. On May 9 Ulysses S. Grant directed Ferrero to dispatch his black troops to guard the area between Dowdall’s Tavern and Chancellorsville, just east of the bloodied and burning battlefields. They reported to fellow Ohioan Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, commanding officer of the Calvary Corps of the Potomac. He sent the 27th to a position between Ely’s Ford Road and Furnace Road. The USCT, which still had not experienced any frontline action, grew more apprehensive. Richmond newspapers reported that the black troops had been wantonly destroying personal property and “assaulting defenseless females.” Although untrue, the accounts further riled the Southern locals, and the knowledge of this, plus the regiment’s location, just west of Chancellorsville and within enemy territory, combined with the loss of sleep from the constant nocturnal marching, increased the stress of the untested black troops.22

On May 10, 1864, as the clouds dropped rain on northeastern Virginia, the fighting at Spotsylvania Court House intensified. The ground trembled as the roar of cannons and artillery grew more intense. As the days passed, rain chilled the night air but could not wash away the thick smell of gunpowder or provide any relief from the daytime heat. Then, at 9:00 A.M. on Friday, a quiet fell over the camp. News of a rebel retreat and the possibility that the Union had taken Richmond spread quickly to the men in the back lines, who had been thus far spared from the horrors of battle. But it proved to be only a temporary suspension of the fighting, and the deafening noise that grated on the nerves of the untested soldiers soon resumed.23

The men experienced constant picket fire that weekend, and by Sunday evening, in an attempt to avoid the danger, the IX Corps moved their encampment four miles to the east. The new site was hardly better, and the black soldiers were “attacked by guerillas” as they tried to set up their tents on muddy ground. That evening Ferrero ordered the men into formation in preparation for a battle against Confederate cavalry. With Major Neilson gone and Lieutenant Colonel Blackman still in Ohio on recruiting duty, the 27th lacked a commanding officer and three companies. Those present with the regiment watched from their position in line as Ferrero ordered the 23rd USCT, a regiment raised in Washington, D.C., to support the 2nd Ohio Cavalry. Together they faced the enemy stationed nearby at Piney Branch Church. The 23rd performed well, successfully driving the enemy away from the Union’s supply train. As the Ohio cavalry followed in pursuit of the enemy, the 23rd rejoined the 4th Division. The black troops, who could finally say that their division had “seen the elephant,” returned to protecting the wagon trains.24

Although the soldiers somehow rested that evening, they awoke to a foggy, cool Monday morning with warnings of an impending attack. Instead of a fight, though, the army treated the support troops to fresh beef for the first time since they joined the corps. The enjoyment provided by the nutritional delight lasted only a short time, however, and by 2:00 P.M. on Tuesday they had once again changed position. Grant ordered Ferrero to move the division closer to Fredericksburg, and after a short, three-mile jaunt, the division made camp in the woods near Salem Church. Here the men encountered a different kind of enemy, as the trees provided a haven for spiders, lizards, and snakes. They soon realized that the pests were only a minor inconvenience compared to unfolding events.25

That same day authorities arrested Levi Beer near Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania. The provost marshal of the Fifteenth District sent the alleged runaway to nearby Harrisburg under special guard because, the marshal said, he had not been “ordered as to what disposition to make of colored deserters.” It is unknown how Beer ended up in the state of his birth, how he became separated from the other missing soldiers, or if he had intentionally gone his own way. Possibly he left the regiment in early May simply because he wanted to see his wife, whom he had left in Columbiana County, Ohio, or maybe he was upset about his demotion from corporal in Company B the week before. Beer learned that he would be sent back to his regiment, under special guard, where his own commanders would determine his fate. As for Benjamin McCoglin and Preston Mosby, they were not so lucky: they were captured and imprisoned by Confederates. Unbeknownst to their officers and comrades, McCoglin found himself on the way to a Southern prison in Lynchburg, while Mosby ended up in Richmond. And although Bobson’s superiors believed that he had left willingly, he died in the makeshift hospital set up in Crumpton’s Tobacco Factory in Lynchburg. He was buried there not long after his disappearance, most likely also as a prisoner of war.26 Meanwhile the officers and soldiers of the 27th continued to endure along the Virginia front.

By mid-May the weather had turned dry and pleasant, as spring flowers blossomed in the Virginia countryside. Capt. Albert Rogall of Company G noted that all of “nature [was] rejoicing except the men”; the soldiers of the 27th had been under constant threats of attack as the fighting nearby escalated. Although the situation was uneventful along the regiment’s picket lines, on May 19 Confederate cavalry and artillery attacked the left and rear positions of the 4th Division. After the rebels failed to break the line, Edward Ferrero suggested to his superiors that he should move his men closer to Fredericksburg, complaining that he lacked sufficient cavalry to protect the black troops from what had become almost daily menacing from the enemy.27

Grant ordered Ferrero to move the wagons and his troops along Massaponax Church Road and then turn southward toward Bowling Green, Virginia. On May 21, as the Army of the Potomac terminated the engagement with the enemy at Spotsylvania Court House, the 4th Division hastily departed from the hazardous position. That evening they encamped on Telegraph Road three miles south of Fredericksburg, and the next morning they resumed the movement to safeguard the supply train. By May 24 they had reached Bowling Green, having on the way lost several of the soldiers in the division, who had been shot by rebel guerillas. The men attempted to settle in after their arrival in Bowling Green, but it was an exceptionally warm evening and they were tired and hungry, as once again the food supply had not reached the division. In the distance, the sounds of a thunderstorm mingled with the noises of warfare.28

In the meantime, Grant had officially incorporated Burnside’s IX Corps into the Army of the Potomac, which gave Meade full control over the troops. The leadership change meant little to the black soldiers, who continued to serve as guards as they marched in extremely hot weather almost daily during the last two weeks of May; it was not uncommon for the men to walk twenty-five miles a day. Although the black troops rarely encountered any fighting, the hot temperatures, rain, mud, constant movement, lack of sleep, and poor rations continued to take a toll on them. On May 29, after they crossed the Mattapony River, the men were overwhelmed by the deficiencies, and near midday, as they marched through the rural countryside, many in the division confiscated chickens. During the war, the army often had to resort to foraging to help feed troops, and although there were policies for such actions, there had been little time to drill or train the men concerning acceptable guidelines. As a result, the practice became a problem both on May 29 and during the days following, and officers of the 27th had to punish several of their men for taking more Confederate property than the regimental commanders felt permissible. Once under control, the troops again took to the roads.29

Late in the afternoon on Tuesday, May 31, they crossed the Pamunkey and camped on the south side of the river only fourteen miles from Richmond. As the 4th Division moved further south, the number of liberated slaves seeking refuge increased, and so did the deafening sounds of cannon fire. The Army of the Potomac had crossed the waterway a few days earlier as part of Grant’s plan to sweep around Robert E. Lee’s right flank in an attempt to reach Richmond before the rebel troops did. Instead, the enemies collided at Cold Harbor on June 3, a day that proved especially deadly for the Union, with over seven thousand casualties to fifteen hundred Southern losses. The seemingly endless line of wagons filled with injured and dying men became entangled with those soldiers returning from battle and the black troops who labored to the rear of the action. Ferrero’s division encamped near Old Church Tavern for the next two weeks, where they provided guard and fatigue duty for Meade’s forces.30 With the realities of battle so close by, some of the men must have wondered if they really wanted to experience the front line.

The 27th participated in a variety of activities near Old Church Tavern. The men served on picket duty and dug rifle pits. They also built breastworks, long ditches with raised earthen fronts facing the enemy that were protected by felled trees with sharpened ends known as “abatis.” Members of Company G had a slight reprieve from the physical labor when command detached the soldiers to take 450 rebel prisoners to White House Landing, the closest Union depot, but that was a short-lived respite. The demanding work left little time for the men to become bored, but illness and injuries still plagued the regiment. Charles Qualls fell while he and seven other men carried heavy logs to help build breastworks, and spikes protruding from the logs struck the nineteen-year-old farm laborer in the knees. The injury proved so severe that Qualls was sent to L’Overture Hospital in Alexandria for treatment. The constant dampness from the previous weeks took its toll on many of the soldiers, causing them to contract rheumatism. Then, when the rain finally subsided on June 5, the ground dried out quickly, creating clouds of thick dust that swept through the camp and around the men as they performed their daily duties. Although it did not rain at all the rest of the month, digging wells in the Virginia soil provided plenty of fresh water to help alleviate some of the discomfort caused by the dryness and the dust. But the rising daytime heat caused other problems, leaving some of the men with headaches, heat prostration, and sunstroke.31

Despite the disagreeable circumstances, the men realized the significance of their presence in Virginia. In early June the 27th helped the 4th Division to free almost five hundred local slaves and transport them to White House Landing. From there the army sent the fugitives to Washington, D.C. Also, some of the black soldiers had another opportunity to participate in a minor offensive. The 23rd USCT suffered only minimal casualties and performed admirably on June 11 when they supported Union cavalry pickets near Shady Grove Church. The success belonged to the entire division, though. Their valor spread hope that once the war did end no one could deny the value of the black soldiers’ service to their country. They hoped that their achievements on the battlefield would lead white Northerners to recognize African American citizenship rights implied by their military duty.32

Meanwhile, Levi Beer, still under arrest for desertion, finally returned to Company B, fearing how his recent failure to fulfill his military obligation would be addressed. However, neither the divisional nor his regimental officers punished the soldier beyond the apprehension and transportation charges. The $32.25 cost meant that the private would lose almost five months’ pay, but the minor penalty indicates that he most likely had been AWOL and not a deserter, and that the discipline meted out to him by the officers of his regiment and division was rather fair. The Pennsylvania officer who had arrested Beer, on the other hand, had assumed that the black soldier was a deserter and would face treatment for the offense different than that given white soldiers. Beer’s case illuminates the difficulties officials faced when they attempted to interpret and apply army policy to the USCT and how most white leaders who served in the volunteer and regular army often operated under nineteenth-century ideas of racial subordination. Yet Beer served as an exemplary soldier for the rest of the war.33

The war did not pause for such concerns. On June 10 the eighth company of the 27th USCT left Camp Delaware in Ohio and traveled to Old Church Tavern. As Company H prepared to join the 4th Division, Meade ordered Ferrero to prepare his troops for another march. Two days later, the soldiers of the 4th Division replenished their packs with clothing, rations, and ammunition, and that evening they departed at 8:00 P.M. and marched twelve miles; they arrived at White House Landing at 3:00 A.M. on Monday. Once again they guarded the supply train for the Army of the Potomac, which Grant had directed toward Petersburg in a new attempt to capture Richmond. The division covered almost forty miles over the next three days. The black soldiers in the Ohio regiment must have questioned if they would ever have another chance in battle.34

The 27th USCT crossed the Chickahominy River late on June 16 after marching nineteen miles. They were on their way to rejoin the IX Corps, already outside of Petersburg. Cannon fire in the distance marred the experience of viewing the majestic scenery around the waterway. The noise came from the forces of Meade and Benjamin F. Butler attempting to take the city. On the evening of June 17, the 4th Division crossed and then encamped on the James River near a platoon bridge, relieving the VI Corps. After almost two months of constant movement guarding wagons, a task the men performed successfully, they prepared to join the siege on the main Confederate crossroads leading to Richmond. They were not the only black soldiers, as Butler’s Army of the James had arrived in early May. His failure to capture Petersburg had precipitated Ulysses S. Grant’s decision to move the IX Army Corps to the area. In total, thirty-eight USCT regiments, the largest assembled for any Civil War operation, participated in the attempt to break through the Confederate trenches. On June 18 Ambrose E. Burnside relieved the 27th and the 4th Division from guard duty and the next day sent them to the front.35

Petersburg, Virginia’s second largest city, with over eighteen thousand residents, sat on the Appomattox River at its juncture with the James River. With twenty tobacco factories and six cotton mills, it was an important commercial center. Located twelve miles below City Point and twenty miles south of Richmond, it was a crucial intersection point between the Confederate capital and the majority of the South. A total of nine wagon roads and five railroads made the urban center the main supply terminal for Lee’s army. In addition to the tracks between the two major cities, the City Point Railroad ran eastward out of Petersburg, while the Southside Railroad ran westward to Lynchburg. Two lines of tracks headed southward, the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad on the east and the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad from the west side of town.36

Grant believed that Richmond would not survive if Petersburg and its railroad system fell, so in early June he began to move Union troops toward the rebel stronghold to finish what Butler had yet to achieve. At the time, Lee had only three thousand troops protecting the city. After a failed frontal attack on June 9, Meade attempted a second assault on June 15. Black regiments from the XVIII Corps, including Ohioans from the 5th USCT, participated in the unsuccessful fight. On June 17 and 18 Union forces tried again, but to no avail. By then Lee had repositioned his troops, including Richard H. Anderson’s I Corps and Ambrose P. Hill’s III Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, who were supported by Pierre G. T. Beauregard’s I Corps of the Army of the Potomac. The rebels increased their defenses to include over fifty miles of dugouts and trenches, from north of the capital to the south of Petersburg, in an effort to protect the gateway to Richmond. Grant’s forces dug in on Petersburg’s eastern and southern boundaries, and over the next several months he ordered his officers to break through the center, while at the same time he made repeated attempts to flank around both the western and eastern lines. The numerically superior Union troops continued to extend its offensive lines in order to stretch and hopefully weaken Confederate manpower. That summer, black troops under Butler’s command assisted Northern forces southeast of Richmond, while Burnside’s USCT participated south of Petersburg.37

Just after the siege began, Burnside requested permission from Grant to exchange some of his troops. He wanted to trade his black 4th Division to the Army of the James for some of Butler’s white regiments. Although Meade eventually agreed, Burnside could not collect his men for the deal, as Meade continually divided and reassigned the USCT to labor duties that kept them essentially out of reach. With no time to rest their blistered feet, the 27th went right to work when they reached the Petersburg front. First they and the rest of the 4th relieved the IX Corps’s 2nd Division from picket duty in the front trenches so that the white soldiers could participate with the rest of Burnside’s troops in an assault on the Confederate lines. At least one of the officers of the 27th, Capt. Albert Rogall, did not believe his inexperienced troops could handle the situation. He wrote in his diary that the “niggers are pushed forward though I am certain they will never do on account of being too green troops.” His unpleasant disposition was largely a reflection of his disappointment that he had not received a commissioned rank above captain, as well as his opinion that the U.S. Army of volunteers lacked professionalism. But his negative comments about the preparation of the black troops were legitimate, especially with the issues related to the officer staff that plagued the regiment.38

As the weeks passed and the Union failed to break into Petersburg, the 27th moved repeatedly to where its labors were most needed. First they supported Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps in an attempt to extend the defensive line from Old Norfolk Road to Jerusalem Plank Road. Some of the men then moved to Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock’s II Corps near the left flank at Jerusalem Plank Road, while others helped to construct Fort Warren, about a quarter of a mile south of the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad. The black soldiers often found themselves in the back lines, where they constructed defensive positions. Despite their civilian experiences as laborers and farmers, the fatigue duty proved difficult. Some of the hardest work included building bombproofs. First the men had to cut enough wooden poles to create a four-foot-tall, three-sided building. They laid more poles over the top to create a roof. Then they dug the dirt several feet deep around the building on three sides and threw the loose dirt onto the roof, up to three feet thick, for further protection. Soldiers connected the bombproofs with open trenches, which zigzagged across the defensive lines.39

Time spent in positions that seemed far enough from the front did not mean that the men in the 27th were out of harm’s way, and they often found themselves under heavy picket fire. During one of the first nights in the field, the men slept in small rifle pits. When Southern cannon fire hit the edge of the dugouts, the disturbed earth partially buried some of the men. Other times the shell action became so heavy the men had to retreat toward the woods nearby. Quartermaster Nicholas A. Gray wrote to his wife that at night he watched from his tent as the cannons “burst in the air over our boys heads” and how “long before this vaporous smoke could go out or disappear another and another would come in the same vicinity.” The constant movement, along with the protracted workdays and dangerous conditions, made it an especially trying time for the green troops. Then, on June 19, the 27th moved much closer to the front. At Prince George Court House they helped to construct defensive positions for the IX Corps’s right flank as part of the Union’s second line. They joined a number of white Ohio troops, including the 95th, 134th, and 138th OVI, all “one hundred day” regiments. As the soldiers toiled under the scorching sun, they were so close to the enemy lines that they could see the rebel armaments firing at them.40 The conditions threatened all of the Ohio regiments.

The men attempted to adjust to their new role. The work was at least as tiring as their previous experiences of marching and guarding, but the increased exposure to artillery and cannon fire dramatically amplified the danger. The 27th suffered a number of casualties. When Joshua King, of Company A, claimed to have ruptured his left side from the heavy lifting, officers sent the Urbana man, already weakened by chronic diarrhea and piles, to the hospital in City Point. On the other hand, after a shell hit William Darlington’s head, he treated the injury with tobacco and water dressings, the Company B sergeant preferring his own medicinal knowledge to that of the army surgeons. Several others hurt by gunfire or who suffered from illness also chose not to see a doctor. Recalling their days back at Camp Delaware, many of the men in the regiment held a low opinion of the army’s medical staff.41

By the end of the month, Burnside ordered Edward Ferrero and his troops back to Jerusalem Plank Road to once again support the II and V Corps. No matter where they moved, which they did frequently that summer, the work and conditions made survival difficult. The situation was deplorable. It was extremely hot and dusty along the Petersburg front. To help battle the elements, some of the men put arbors of bushes around their tents, hoping to escape the discomfort caused by hours of work under a blazing sun while in the trenches. But the soldiers still endured heat prostration, sunstroke, and severe headaches. There was little clean water available, and usually the horses and staff received rations first, making food preparation difficult, and although the men appreciated the fresh beef when it was available, the butchering proved unsanitary. As a result, chronic diarrhea remained the soldiers’ constant companion. William J. Anderson, a thirty-year-old farmer from Ross County, suffered terribly. His food passed right through him, undigested. For nourishment he soaked bread in water and drank the cloudy mixture, eventually becoming so weak that he could not perform guard duty.42

The poor diet and dehydration combined with heavy marching and work details caused many of the soldiers to develop painful hemorrhoids. Lice and snakes further irritated the men, and those healthy enough made killing the vermin a camp sport. The noise level, too, once the background clamor to the movement toward Petersburg, was deafening, and the cannon and musket fire led to temporary or more serious permanent hearing loss for some of the men. But what proved to be the greatest menace were the camp diseases. Hospital steward William C. Ross, who treated the men in positions away from camp who did not have access to the inadequate regimental hospital, helped the men as much as possible. He dispensed whatever medicine he could gather, but the maladies still spread quickly to too many soldiers.43

Many of the officers in the USCT suffered from military life more than their peers in white regiments, as they often had to do double or triple the duty. Field and staff officers from black troops sometimes reported that not only were they understaffed but they lacked men capable of serving proficiently as noncommissioned officers, so they passed the additional work on to white officers who were busy with their company duties. Some of these problems plagued the 27th. The commanding officer, Lt. Col. Albert M. Blackman, was still in Ohio recruiting and Maj. William G. Neilson remained in the hospital, so Lt. Col. Charles J. Wright of the 39th USCT assumed temporary control of the regiment. Company C had two officers unavailable that summer. Lt. Frederick J. Bartlett was in the hospital for three months, and Lt. Charles A. Beery could rarely report for duty because of a severe case of syphilis. The absence of other officers for a variety of reasons also contributed to the overburdened field and staff, and as a result, the tempers of the officers who were present shortened and their patience and concern for the black troops decreased. This contributed to the soldiers’ suffering. Although he implied that it was the fault of the medical staff, a bitter officer of the 27th reported that one of his men from Company G, Cpl. Thomas Perry, “died for want of attendance.”44

On June 26 Edward Ferrero reviewed his troops, which provided a slight reprieve from their monotonous and dangerous assignments. For the men it proved to be simply a different type of work, as their preparation for inspection under the hot summer sun required a great deal of effort. Soon after, the officers began drilling their companies as time allowed, and more important, during the first two weeks of July the fighting slowed somewhat around Petersburg. It became much quieter, as fewer cannons were exploding along the front.45

The daily work continued, though, the black soldiers toiling with minimal comforts and with limited relief. The United States Christian Commission delivered fresh vegetables sometimes twice a week, and on July 4 the United States Sanitary Commission passed out pickles, onions, and dried apples. But these were only temporary diversions from the discomfort and difficulties of military life in the Virginia fields. It became increasingly more dry and dusty, as no rain fell between June 2 and July 16, and though the current relative quiet was a welcome relief, it unfortunately provided additional opportunities to think of home. The men missed their families and friends, and the infrequency of mail deliveries, and the fact that many of the soldiers were illiterate and had limited communications through letters, made their homesickness more painful. Although James H. Payne read and wrote letters for some of his comrades, the men were often too tired to take advantage of his assistance. After completing the physically demanding work each day, Ambrose E. Burnside’s “hewers of wood and drawers of water” often fell into their tents, sometimes too tired to eat their scant evening rations.46

In early July the 27th helped to build two large forts connected by a series of breastworks. Because of the heat, the soldiers often worked at night. As a result, they had to sleep during the day, which was almost impossible with the bright sun, the constant picket fire from the rebel lines, and the annoying flies that descended upon the helpless men. Once the construction was completed, commanders had some of the soldiers exchange their tools for guns and sent them into the trenches to support Warren’s V Corps. Although anxious to break from their taxing labors, the danger of being so close to the enemy quickly became apparent when Jeremiah Ward of Company C received a gunshot wound to his right hand. Ohio newspapers conveyed the idea that it was “all quiet” in the Army of the Potomac except for angry rebels who “were incessantly firing” upon Burnside’s “large number of negro soldiers.” On July 14 Ferrero reported that 1,000 of his 6,650 troops were serving on picket duty. George B. Meade showed his displeasure when he questioned whether the black men were capable of protecting the lines by performing picket duty, and several days later he replaced Ferrero’s troops along the line with white soldiers.47

The black troops south of Petersburg once again served in their primary duty as laborers. They reshaped the Virginia countryside as they dug trenches, built redoubts and entrenchments, and chopped trees for lumber. The heavy work was stressful for the soldiers: Robert Cannon, a nineteen-year-old private originally from Tennessee, ruptured his left side when he carried heavy logs used to build a bombproof. It certainly was not what most of the 27th had enlisted to do. The soldiers therefore did not know how to interpret the rumors that circulated in the camps by mid-July. Although it explained why their officers suddenly showed interest in training the soldiers for nonfatigue duties, the men wondered if they would really fight in the battle supposedly being planned by the high command. Henry Alexander, a forty-four-year-old former slave from Owen County, Kentucky, wrote to his wife that they had “no fight yet nor is there any present prospect of one.” Lt. Albert G. Jones in B Company held a different opinion and wrote to his fiancée in Cleveland that it was well known that mines were planted under the rebels and he expected the blasts to go off any day.48

The “big fight” was not a rumor to the ranking officers. After Burnside learned of the declining conditions in Petersburg, he began to seriously entertain an idea presented by Brig. Gen. Robert B. Potter of the 2nd Division to use a grand explosion to smash through Confederate defenses. He believed that the low morale and insufficient food supplies in the city meant that the Southerners living there had to be ready to break. This was the opportunity the Union leadership had been waiting for. After he convinced Ulysses S. Grant, Burnside developed an unusual plan. He used members of the 48th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, many of whom were Joshua K. Siegfried’s former men, and coal miners by trade, to dig a tunnel underneath the network of trenches to reach the impenetrable Confederate four-gun Elliott’s Salient only 130 yards from the Union forces. Once the underground pathway was complete, they planned to detonate a mine containing six tons of gun powder. After the explosion, the plan called for Northern forces to storm through in a three-pronged attack, one line going into and through the disrupted earth while two separate forces went around each side to clear out resistance in the rebel trenches. The goal was to reach and successfully take Cemetery Hill, a major Confederate position about four hundred yards from the Union trenches, and then continue into Petersburg before startled rebels could recover from the blast. The capture of Richmond was sure to follow.49

Burnside informed Ferrero that the 4th Division would lead the charge, with the 43rd USCT in front, and that he should begin immediately to prepare the men. Burnside chose the black troops because he believed that they were the most rested of his army. He thought that his white troops were too drained by their losses from battle, picket duty, and illness. Of course, the African American soldiers were just as worn down, and, more significantly, they had less experienced officers, making Burnside’s reasoning questionable. He defended such criticisms by arguing that the blacks would only enter first and that tested white troops would actually perform the most important task of capturing Petersburg after the USCT had secured Cemetery Hill. Burnside instructed Ferrero to inform Siegfried and Col. Henry G. Thomas, commander of the 2nd Brigade of the 4th Division, of the upcoming event. In preparation for the attack, Ferrero wrote to the assistant adjutant general that Lieutenant Colonel Blackman was needed, as “no field officer of the regiment is with it,” and that “an officer has to be detailed from another regiment to perform his duties.” On July 14, the War Department sent word to the superintendent of volunteer recruiting services in Ohio that the secretary of war had requested that Governor Brough release Blackman from recruiting duty and send him to the front with any new enlistees that he could bring.50

On July 17 an impatient Ferrero sent word to the IX Army Corps headquarters that his men, who were supposed to help lead the assault, needed time to rest and prepare for their important role. He explained to his superiors that the 4th Division had been performing an enormous amount of fatigue duty, often at night. Not only were the men exhausted, but the non-ending toil had left him little time to train them. The complaint was not an attempt to get out of the upcoming battle; it was a plea to participate. Ferrero firmly reminded Burnside of the leader’s promise to finally engage the entire division of black troops in a planned military action. Yet the only training Ferrero could fit in during the demanding construction schedule was to pull out one regiment a day to drill in the two weeks before the planned assault—although Lt. Robert Beecham of the 23rd USCT remembered only three to four hours of instruction. Capt. Albert Rogall made four references to 27th’s “preparations for a big fight” in his journal during the weeks before the explosion at the Battle of the Crater, but the military inexperience of the blacks became painfully clear when they practiced with their weapons. One surgeon reported that in a single day he had to perform seven thumb operations after the training began.51

Soon the stale atmosphere around the Petersburg front began to change. On the evening of July 19 it rained for the first time since early June, which brought relief from the dusty conditions in camp. On July 22, after weeks of being shuffled between various divisions of the Army of the Potomac, the 4th returned to Burnside’s IX Corps. The 27th went into the entrenchments along the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad and relieved the 3rd Division from picket duty. Two days later, Joshua K. Siegfried inspected the trenches occupied by his men. He found the sanitary conditions acceptable and his troops “generally vigilant and at their places.” But Siegfried was not happy with the circumstances. He complained about his division’s proximity to the Southern lines and requested that his men, who slept in their tents unprotected, be allowed to build bombproofs in the rear of the lines. Then, on a rare chilly and foggy summer morning, the black division awoke to orders to prepare for a possible Confederate assault. Although the rebels did not attack, terrible storms that night flooded the holes dug out of the Virginia ground. Unbearable heat followed the downpour, and tensions increased along the Petersburg front.52

By July 26 the workload had intensified for Burnside’s troops. While situated in an extremely dangerous position, irritable officers pushed the men to complete more rifle pits and earthworks to protect the left flank of their rear lines. Black and white soldiers worked in close proximity within the maze of trenches and redoubts along the front. Despite the conditions, the USCT proved that they were capable, and overall the IX Corps welcomed their service. Although they dealt constantly with discomfort and danger, the black soldiers successfully fulfilled their duties and made an important contribution to the Union efforts. As July 1864 came to an end, the 4th Division prepared for their role in the upcoming attack on Confederate forces. This time they would use their guns, not picks and axes. The men in the 27th realized that their opportunity to display their abilities as fighting men was only a few days away.53

Meanwhile, under pressure from Meade and Grant, Burnside restructured his plans for the exploding of the mine. Meade argued that the black troops lacked sufficient military experience to lead the charge, and later Grant recalled that neither he nor Meade wanted to be accused of “shoving those people ahead to get killed because we did not care anything about them.” Meade also feared the political ramifications if the experiment failed. Grant, who did not want to risk Lincoln’s upcoming reelection bid on a potentially negative northern reaction, agreed. Burnside had to choose one of his white divisions to lead the charge after the blast, so he directed the leaders to draw lots to determine the order of procession. The result placed Gen. James Ledlie, the least capable of the three, and the 1st Division in the lead of the charge. The high command also replaced the original three-pronged approach, for which the IX Corps had drilled in a somewhat limited capacity, with a plan that called for a single direct line of assault. Ledlie was to take his men to the left of the explosion and on to Cemetery Hill. Gen. Orlando B. Willcox would follow along the same path, taking his 3rd Division past the hill and on to secure Jerusalem Plank Road. Robert B. Potter’s 2nd Division was to keep the enemy occupied to the right of the explosion, while Edward Ferrero’s 4th Division followed the path left by Ledlie and Willcox. When they reached Cemetery Hill, the black soldiers would then continue with Ledlie’s men into Petersburg.54

Late on the morning of Friday, July 29, Siegfried and Thomas learned that their brigades had been pulled from the lead charge. Their discomfort grew as the dust and debilitating temperatures hovered over the Petersburg front. That evening the IX Corps moved close to Burnside’s headquarters to wait for their next orders, and that same night James H. Payne held a short prayer meeting for the men in the 27th. He claimed that many “appeared to be greatly stirred up; while sinners seemed to be deeply touched and aroused to a sense of their danger and duty.” But the black soldiers’ cautious anticipation turned to quiet disappointment. During the previous three weeks they had performed difficult labors while occasionally drilling for the assault. Now, placed in the rear of the line once again, their hopes were dashed. For the officers, the changed plans caused serious concerns about their soldiers’ potential success.55

Under a dark moonless sky, the men awaited orders. There was no breeze to move the stale, warm air that early morning. Soldiers waited on the open ground just behind the white troops and the covered way leading to the mine, barely one-third of a mile from the explosives. Around 3:00 A.M. on July 30, officers told the 4th Division to have breakfast. The sleepy men dined on hardtack and raw salt pork and quickly returned to their personal thoughts concerning the impending event. Then, sometime after 4:45 A.M.—later than intended and not as close to the original target as hoped—the earth trembled and exploded open, sending clay, dust, and humans toward the heavens.56

At 5:30 A.M. the Union began to exchange artillery and musket fire with the enemy. About thirty minutes later, Ferrero’s 1st and 2nd brigades heard the order to move into the covered way that opened to a crater in the earth, over 150 feet long, 60 feet wide, and almost 30 feet deep. The black soldiers crouched in the warm, narrow tunnel for another hour and then had to stand tight as wounded troops returned from the fight. The men grew nervous as they watched the battle-scarred soldiers pass, the noise deafening, like “forty thousand juvenile hogs” that “had attempted a passage through a fence and stuck.” At 7:30 A.M. the men in the 27th heard the orders they had been waiting for since their days at Camp Delaware: “Charge!” Ferrero questioned the timing as the path was too crowded to get his men through, but Burnside would not listen and ordered all to proceed. Ferrero remained in the first line of Union trenches as his men attempted to advance toward the other three divisions who remained in the fight. The white troops, especially Ledlie’s 1st Division, who appeared to have had little instruction on the changes made days earlier, had only limited success, and the advance became chaotic. The black troops did not make any progress until after 8:00 A.M. The disturbed ground left by the explosion made it difficult for the troops to proceed as planned, causing the men to push forward in every direction, including down into the deep hole.57

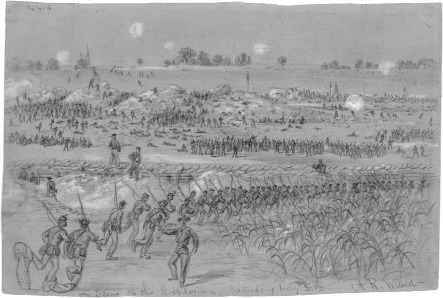

Fig. 8. In 1864 Alfred. R. Waud sketched the black troops on the morning of the Battle of the Crater in Petersburg, Virginia. “Scene of the explosion Saturday July 30th.” (Library of Congress)

Colonel Siegfried’s 1st Brigade, led by the 43rd USCT under the command of Col. Seymour Hall, went first. Soon after, the 30th followed, then the 39th and 27th proceeded. Blackman had failed to reach Petersburg in time, so Lieutenant Colonel Wright of the 39th USCT remained in command of the 27th. The 2nd Brigade, led by Colonel Thomas, followed close behind. Once they emerged from the covered way, the 4th Division ran down a sandbagged staircase for almost a hundred yards through unrelenting gunfire. As they attempted to move left toward Cemetery Hill, enemy canister, grape, and musket bullets landed all around them, pushing the men to the right and toward the crater. James Ferguson of Company B took a shot to his right eye and Jerry Warren, a corporal in Company D, received a flesh wound to his left arm. An exploding shell hit Isaac Noble, a “good and faithful soldier” from Company A, in his left hip, damaging the bone. He fell and lay in a creek while the rest of the men quickly became entangled with the 2nd Brigade and various white soldiers who either attempted to complete their ordered charge or ran away from the carnage.58

Wright continued to press the 27th onward, now lined up with the 39th in columns four soldiers wide. They went in, stepping over the dead and wounded, until they reached a position on the right. In the confusion, David H. Pugh, commanding officer of Company B, hid instead of leading his men. Enemy fire hit Sgt. James W. Bray of Company H in both legs. Sgt. Artis Watson of Company A watched as his friend Matthew Hill, a private from Company H, fell to the ground, hit by a shell above the left ear. Then a bullet went through the twenty-two-year-old Hill’s left leg, just above the ankle. Pvt. James E. Scott shot a man and watched half of his head blow away. Most of the 27th made it through the crater and into the maze of the Confederate trenches, but the men halted at the rebel bombproofs. Lt. Amos Richardson, with his sword in one hand and his revolver in another, called for his men in Company F to “come on.” Then a minié ball hit the twenty-one-year-old officer in the head. Although the 30th and 43rd USCT made progress advancing further to the north side of the crater, it was simply too crowded for the other blacks to follow. Some of the officers tried to keep order and told the men to lie down and hold their position. The soldiers from the 27th waited almost an hour in reserve, while the 43rd went further to the right and successfully charged the enemy. Col. Delevan Bates suffered a nonfatal shot through the face as he attempted to rally the 30th USCT, the ball entering his right cheek and coming out behind his left ear. Two bullets found Lieutenant Colonel Wright as the black Union soldiers attempted to hold on to the rebel works taken in the effort by the 1st Brigade. The soldiers of the 43rd and the 30th captured almost two hundred rebel prisoners, some of whom they killed upon surrender. But their success was short lived.59

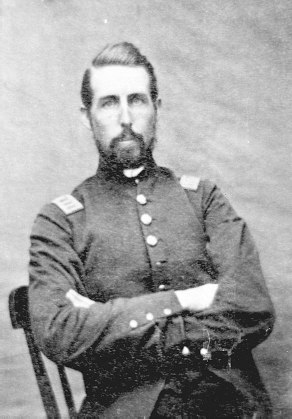

Fig. 9. Capt. David H. Pugh, from Van Buren in Hancock County, Ohio, served in Company B of the 27th United States Colored Troops from March 18 to October 1864. He received a disability discharge for a debilitating illness and a wound received at the Battle of the Crater. (Civil War Photographs, RG 98s. United States Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, Pa.)

When the Confederates recovered from the initial shock of the explosion and assembled their soldiers to defend their lines, the chaos turned to terror as the Southerners let out their rebel yell. They took out their anger on the Union troops, especially the USCT. Soon soldiers Northern and Southern, white and black, became entangled in the Petersburg fields. William Mahone, whose tenacity that day led Robert E. Lee to promote him to major general on the field, sent his men from the 3rd Division of the Army of Virginia into the fight. Confederates attacked the 4th Division ferociously as Thomas’s brigade tried to advance a second time. As a result, the black soldiers of the 2nd Brigade broke and ran over and through Siegfried’s troops. Siegfried and Thomas attempted to lead their troops out of the fighting, but the lack of training, the changed plans, and the inability to hear or see each other made it impossible.60

Most of the 27th under Wright held on desperately in the trenches, where they were joined by some of the men of the 43rd, 30th, and 39th USCT who attempted to withdraw. Most of the soldiers were simply too weak to continue to fight, they had had little sleep the night before, less food, and no water. It also appeared that their position would soon be cut off from any chance of retreat. Wright led the soldiers back to the Union lines through some nearby trees as rebels attempted to stop them. Just as Capt. Alexander S. Hempstead ordered Company F to follow Wright, a Confederate officer demanded his surrender. When Hempstead attempted to flee, his wounded ankle gave out and he fell into a trench as Union soldiers trampled over him. Some of his men carried him to safety near the pines Wright was using as a cover for the retreat, and then they took him back to the covered way. Meanwhile, instead of leading their men, Ledlie and Ferrero sat drinking rum in a bombproof. At 9:45 A.M., without the agreement of Burnside, George B. Meade ordered an end to the assault. The failed leadership, coupled with the confusion on and off the field, had led to an unstoppable disaster and unbelievable slaughter by charging rebels.61

By noon Meade had convinced Ulysses S. Grant that any further advance would be fruitless. He then ordered Burnside, who believed they could still break through and hold what they had gained, to call a retreat. It would not end that easily. Heavy fighting continued for almost four more hours, most of it contained in the hellish pit left by the explosion. Once in the crater, men who attempted to retreat faced chaos and horror, as body parts flew by and blood ran down the dirt walls. Mahone’s troops made a final assault around 2:00 P.M. In some places the men were so close together that firing a weapon became difficult. Rebel soldiers, told that blacks who sought retaliation for Fort Pillow and other atrocities committed against the USCT would not take prisoners alive, came in with unbridled hatred. They resorted to vicious hand-to-hand combat with rocks, pieces of wood, and the barrels of their rifles. Those above threw muskets with bayonets into the crater, blade first. Some blacks fought bravely, but both white and black troops gave in to panic and fear. In desperation, some white Union soldiers fired upon blacks to keep the Southerners at bay. The killing and maiming continued.62

In late afternoon Burnside ordered an evacuation of the crater. Northern guns attempted to keep advancing rebels back to allow the retreat, but instead Union soldiers became caught in the crossfire. The desperate leader then allowed soldiers to try to dig a tunnel to get the men out. Inside the crater, men tried to burrow in and build makeshift defensive walls, using anything they could locate, including the bodies of their dead comrades. With little hope of escape remaining, Union officers ordered the black soldiers to lay down their arms. Understanding the implications, some of the black troops instead fired upon oncoming Confederate troops. As a result, Southern soldiers began using their bayonets on wounded or surrendering blacks. It took a Confederate officer’s promise of fair treatment, and threats of death if they did not comply, to get the black soldiers to surrender. Those too injured to join the other prisoners of war were murdered. The fighting ended just after 3:00 P.M. that afternoon, a devastating Union loss.63

Fortunately for the 27th, most of the soldiers had avoided the bloodbath suffered by other USCT in the crater. But the regiment had a number of casualties. Company C lost the most men that day, including eighteen-year-old Simon Banks and forty-four-year-old Thomas Bibb. Soldiers in other companies suffered as well. In Company B, Robert Cannon received gunshot wounds in both legs, the most serious to his mid right thigh, and Levi Beer took a hit to his back right shoulder. It tore his muscles and fractured his scapula before exiting through his chest. Richard Fox was shot in the stomach, and James Hammond lost his left eye. Both served in Company F. William Underwood of Company G was shot through the left thigh, fracturing his bone. The casualty list also included officers of the 27th. Alfred W. Pinney, captain of Company H, suffered bullet wounds to his right thigh and arm. Capt. John Cartwright of Company A and Lt. Amos Richardson and Lt. Seymour A. Cornell of Company F were killed in action, and no one could locate Edwin C. Latimer, captain of Company C. An escape from the dangerous position in the crater did not ensure safety. Angry Irish troops in the 49th Pennsylvania supposedly “shot a lot of the darkey troops as they came running back after the Rebs re-took the fort.” Most likely not with the same intent, a retreating artillery wagon ran over Sidney Vicks and left the private from Miami County unconscious, with “his right leg broken, both bones, about three inches above the ankle,” as well as two of his left side ribs. Andrew Ely of Company F suffered a chest injury when a fleeing horse trampled his breast.64

Although most of the 27th had been able to make their way out of the trenches around the crater and fell back into the Union lines of defense during the late morning of July 30, the horrors on the battlefield continued long after the attacks subsided. Some of the men took refuge in rifle pits on a hill, while others hid in bombproofs. But many of the soldiers were unable to retreat far enough away from enemy picket fire for safety; the wounded and dying lay unattended in the crater and on the surrounding grounds. Throughout the night the men in the 4th Division could hear the injured crying and moaning, but the fear of being attacked by Confederate forces kept the survivors under cover. On Sunday, the 27th remained in “grave like” holes as they waited for a flag of truce. They wanted to gather their wounded and dead and find a safe place to get some water and food. As the temperature rose to ninety degrees, the wounded screamed, parched from no water, and the deceased bloated in the blazing sun. Meanwhile, Meade hesitated to call a truce; he did not want to admit defeat. Burnside asked, but the Southern leadership wanted the request from Meade or Grant.65

Other Northern troops found themselves left within the chaos of the enemy lines and at the mercy of Confederates. After their capture, some of the white USCT officers refused to give their regimental affiliation, fearing the ill treatment Southerners vowed to inflict upon their ranks. So Southerners tried to force the black soldiers to point out their officers, but the tactic failed. Many of the USCT feared they would receive no quarter. When rebels grabbed John W. Phillips of Company H, he had seen no evidence that he would be spared, but to his surprise his captors put him with the other black prisoners of war, including at least five other men from the 27th. Reports vary, but at least a hundred and possibly over two hundred USCT were captured alive that day. The Southerners robbed the soldiers and then placed them in an open field with no food, water, or cover, where they remained until the next afternoon. Captured Union surgeons, from fear of retribution from the rebels or their own racial beliefs, initially refused to treat the stripped, wounded prisoners. Rebels put some of the captured black soldiers on work detail and forced them to repair Confederate lines or bury the dead.66

On Sunday Southerners marched the Union prisoners through the streets of Petersburg. To humiliate the white soldiers, they mixed the rows of black and white troops. The USCT had no shoes, and many had only their shirts and drawers. The Petersburg citizens taunted the Union soldiers, telling them that they were on their way to Andersonville to die. Most of the Southerners simply looked with silent disdain at the captives, both black and white, although it was remembered later how a white woman had yelled, “That is the way to treat the Yankees, mix them up with the niggers.” For the residents of Petersburg, it was not just the sight of black men in uniform that infuriated them, it was the disbelief they felt at the Northern whites who fought along with them. Angered initially by the trickery of the underground explosion, the Southern citizens’ disgust shifted to the Union’s implementation of a major offensive assault, on their Virginia homeland, that included the UCST in a significant role.67

On the second morning the men boarded cattle cars. The Confederates sent most of the officers, including Capt. Edwin C. Latimer of Company C in the 27th, to Columbia, South Carolina. Trains delivered John W. Phillips, Jordan Arnich, James W. Johns, Napoleon Lucas, and Anderson Smith to Danville Prison. James Griffee was taken to a Richmond hospital and then put to work at the Confederate front. Meanwhile, doctors readied for the onslaught of injured soldiers. Congress had set the number of doctors for each regiment at one surgeon and two assistants. Some of the physicians came from the U.S. Army Medical Corps, but surgeons could also enlist as volunteers. Members of a presidential commission assigned physicians to the USCT, but they often failed to meet the set congressional numbers. Furthermore, few Civil War–era doctors were trained or had dealt with large numbers of patients. Medical knowledge at the time lacked a clear understanding of how to cure many of the diseases that spread through the camps, and many of the physicians had no experience with the type of injuries sustained on the battlefield; overall, most were outright unprepared. And white physicians were often trained to provide different treatments for blacks, believing that African American bodies reacted to illness, injury, and medicine differently from whites. Sufficient medical care for the USCT was therefore unlikely, and for the men in the 27th USCT it was further threatened. Regimental surgeon Francis M. Weld had only one assistant surgeon, Herman Niedermeyer, who remained with the regiment to attend to the daily needs of the soldiers, while Weld usually spent his time serving at the larger corps hospital. Less than two weeks before the Battle of the Crater fiasco, Governor John Brough had written to then assistant adjutant general Charles W. Foster that he was concerned about the medical care provided to the Ohio regiment, as he had heard that the doctors were “negligent and incompetent.” Yet one soldier wrote home that his “officers saw all the time that I had good care.”68

Regimental officers selected black soldiers to aid the white doctors as hospital attendants and nurses. Therrygood Manley of Company C served on detached duty with the Surgeon’s Service at Jackson Hospital near Petersburg, and after the battle the thirty-year-old from Madison County dressed the wounds of many of the black soldiers. The casualties were so numerous that Manley was forced to perform tasks unlike his previous duties: when James Ferguson arrived, his facial bones destroyed from a gunshot wound, Manley did what he could to keep Ferguson alive until a doctor could work on the private’s wounds.69