The men in the 27th United States Colored Troops reacquainted themselves with life in the Petersburg trenches as the summer of 1864 came to an end. The IX Corps’s new leader, Maj. Gen. John G. Parke, took the opportunity to review the organization of his command. On September 1 he reduced his four divisions to three. He disbanded the 1st Division, which had suffered more losses than the others, and sent the soldiers to the 2nd and 3rd divisions. Two weeks later he made the 3rd Division the new 1st Division and reassigned the 27th and the other black regiments in Gen. Edward Ferrero’s 4th Division to the new 3rd Division. The change meant little to the 27th’s leadership, which struggled to fill the officer positions in the regiment. Albert M. Blackman, who was promoted to colonel on September 1, worked to fill the vacancy of lieutenant colonel, and on September 3 he asked the assistant adjutant general of the Army of the Potomac if the captains Alexander S. Hempstead, Sanders M. Huyek, and Isaac N. Gardner would be permitted to appear before a board of examiners to determine who should be promoted. Although his request was granted, Gov. John Brough had already approved John W. Donnellan’s promotion from the 83rd OVI to become the new lieutenant colonel of the 27th USCT, and Donnellan mustered into the regiment on September 13. Blackman did obtain one officer of his choice, although Charles W. Foster of the Adjutant General’s Office pointed out that Blackman failed to follow the appropriate procedures. Albert G. Jones received a promotion to first lieutenant and adjutant while on a leave of absence. He returned to serve as the regiment’s adjutant on October 11.1

The regiment still had vacancies. There was no major present, and no chaplain had been appointed. The surgeon Francis M. Weld had arrived in early May, but since July had spent most of his time at the division hospital. Battle losses and illness had reduced the number of company commanders. Albert G. Jones reported to the Ohio State Journal that only one of the seven captains who had left with the regiment in April still served. Likewise, the regiment’s noncommissioned support also suffered. Sgt. Maj. Charles F. Woodson had been sick all summer, spending most of his days in the hospital, and George L. Smith, the commissary sergeant, had only one month of experience in his position. There was some good news, though. The newly promoted captain Matthew R. Mitchell had recovered from the wounds that he received while on picket a month earlier and returned to Company H. But with much else the same, the soldiers in the Ohio regiment remained in the rear of Petersburg’s lines once again, where they carried axes and shovels instead of rifles.2

In September the Union finally had a concrete reason to celebrate. After commencing his march through the South, Gen. William T. Sherman captured Atlanta on September 2 and helped place Abraham Lincoln in a better position for the upcoming election. They celebrated along the Petersburg front by opening their artillery at midnight in a display that looked like fireworks. Then, on September 22, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant ordered a one-hundred-gun salute fired upon the rebel front to announce Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s victory in the Shenandoah Valley over Gen. Jubal Early.3

For the men in the trenches it was otherwise fairly quiet, at least from military sounds. One concerned soldier remarked on the other noises present in camp, stating, “Profanity has reached such a pitch, that it very often shocks the ears of even wicked men.” Some of the men believed that the inability to hold regular religious meetings had facilitated the poor behavior of the black troops. The lack of an appointed chaplain to the 27th most likely also contributed. Despite the alarm over the situation, there was simply little energy or time to adequately administer to the soldiers’ spiritual needs.4

Throughout the month the 27th toiled continuously. They helped to construct and fortify supply lines that secured a more steady delivery of foodstuff from City Point. Some days they worked late into the early morning hours fortifying breastworks. Other than having a few assignments in the picket lines, the men provided the work force for the IX Corps, felling lumber more than Confederate soldiers. Yet throughout their labors they remained under a constant threat of attack and on more than one autumn night officers called the men to the ready.5

As the weather cooled in late September, Grant believed it was time to once again move against the Confederate entrenchments south and west of Petersburg. He directed Gen. George B. Meade and Gen. Benjamin F. Butler to coordinate a two-front attack to commence on October 5, but changing his mind based on events in the western theater, Grant decided to move before Gen. Robert E. Lee’s troops returned from the failed attempt to stop Sheridan. He also wanted to take advantage of the extra manpower provided by the recent arrival of fresh one-year recruits. First Grant sent Butler’s X and XVIII Corps to hit from the east, but this was mostly a diversionary tactic in order to facilitate Meade’s operation. Later, on September 29 and 30, Butler’s troops met the enemy near Chaffin’s Farm and New Market Heights, where black troops proved highly successful to the Union cause. Ohioans from the 5th USCT, Powhatan Beatty, Milton M. Holland, and Robert A. Pinn, received the Congressional Medal of Honor for their contributions.6

Meanwhile, the 27th prepared to participate under Parke’s command. His charge, to stop the Confederate supplies coming out of the Shenandoah Valley and entering Petersburg and Richmond on the Southside Railroad, was Grant’s primary interest. The Union took control of the City Point Railroad and the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad in June, and the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad in August, but Grant needed to further weaken Lee’s forces. He ordered Parke and the IX Corps to break through the westernmost line of Southern defenses. On September 25 Parke placed the divisions of Orlando B. Willcox and Robert B. Potter in reserve to prepare for the new assault. He moved the 27th and the 3rd Division into the front trenches to occupy the opening left by the white troops between Fort Davis and Fort Howard. The men once again traded their axes for firearms.7

This time the black soldiers performed more than defensive picket duty. Parke issued orders for several reconnaissance missions in order to locate the weakest point along the Confederate lines. On September 28 Edward Ferrero sent out a scouting party from the 1st Brigade of his 3rd Division. When they returned to camp, the men reported that they had come upon almost a mile of lightly protected rebel defenses near Vaughn Road, also saying that when they pushed to within 260 yards of the enemy lines, they saw only a few Confederate cavalry. Later that night rebel pickets fired upon the Northern soldiers as they changed duty. Ferrero prepared the 1st Division for a possible attack, but it proved to be a false alarm caused by overzealous reports from his underexperienced troops.8

The exaggerated claims of rebel activity from the USCT caused Ferrero to question the scouting reports, so the next morning he decided to check for himself. When he led 750 men from the 27th USCT into enemy territory, he discovered that the first party had not reached as far as they believed they had and had simply seen a group of rebel scouts. Ferrero and the black soldiers in the Ohio regiment found that the enemy actually had a highly fortified defensive position. Ferrero decided against an advance with his inexperienced troops and returned to camp to report his findings to Parke.9

As the 27th made their way back to the trenches, the white divisions of the IX Corps prepared to take a more direct action. Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg of the 2nd Cavalry Division reported that he was prepared to “demonstrate toward Poplar Spring Church or wherever” his men could find the enemy. Early Friday morning, Parke led his 1st and 2nd Divisions along with Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren and two divisions from his V Corps to support Gregg. A total of twenty-four thousand men marched toward the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad on the road leading to Poplar Spring Church. Although they were unable to break through, they extended the Union position westward toward the Southside Railroad.10

During the fighting, the 3rd Division remained in the trenches west of Jerusalem Plank Road between the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad and Fort Alexander Hays. The 27th and their comrades successfully held the Union position when just after noon on October 1 enemy fire hit their lines. This lasted only a brief time, but officers placed the soldiers at the ready. As the men waited, it began to rain. Then, just after 5:00 P.M. Maj. Gen. William Mahone’s men tried to attack the black troops. Although they had lined up for battle, most of the 3rd returned to the trenches to avoid the assault while the rain drove the Confederates back.11

The wet and gloomy weather continued for the next several days, and heavy downpours stopped action for some time. Early on the dark, muddy morning of October 3, the 48th Mississippi of Brig. Gen. Nathaniel H. Harris’s brigade made a second attempt on the black picket lines near Jerusalem Plank Road. Even though the men had suffered from the cold and shortage of rations during the previous days, all the rebels could do was to startle the outposts of the 3rd Division. The black soldiers remained calm, and instead of challenging the rebels, some of the USCT retreated to seek assistance. The news of the Confederate effort spread quickly through the lines, and soon the black soldiers stationed farthest west on the line opened fire and sent the rebels back to their own trenches.12

Northern leadership failed to recognize the black soldiers’ ability to hold the line. In part it had to do with the information that came from several captured southerners who had reported to Union officials that during the attempted attacks by Confederates the rebels had successfully apprehended some of the black troops without any resistance. General Meade was furious and without any further confirmation lashed out at Ferrero. The stunned leader had no idea what his superior officer was talking about, as he knew only of a few USCT killed and injured. Later that morning Meade learned that in fact the line had held, but it did not change his overall view of the blacks in his command.13

Once again, Ulysses S. Grant had implemented a costly plan with only partial success. The Union paid with three times the casualties as the rebels. Near Richmond, Benjamin F. Butler’s troops took Fort Harrison and pushed the Union lines to Darbytown Road. Meade’s men extended their lines to Peebles’ Farm, west of the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad, and added a mile and a half to the network of trenches southwest around Petersburg. Although they failed to capture the Southside Railroad, the Northern troops stretched out Lee’s army to the point that the Confederate general openly discussed the possibility of losing Richmond if he did not get more men and supplies.14

The expansion of Union lines meant a return to fatigue duty for the men of the 27th. By October 5 Ferrero had followed orders to remove his 3rd Division from their position near Fort Alexander Hays. They marched west of the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad to relieve Maj. Gen. Gershom Mott’s division of the II Corps near Poplar Spring Church. Parke stationed the 27th in the rear of the IX Corps defenses, between Fort Cummings and Fort Dushane on Squirrel Level Road. Despite proving their military ability in the recent action, the black soldiers’ return to the back lines lasted for several weeks. They worked hard, building two redoubts on the front line, three redoubts along the flank, and two more on the rear line. In addition to the construction duty, they worked felling trees to create parapets protected by slashing timbers that connected each of the redoubts. Only a few of the men reported to picket duty. For Joseph G. Stevens of Company E, his time in the front lines resulted in a bullet wound to his right side. Doubt must have nagged at the tired soldiers in the 27th, who carried tools instead of muskets. Were they fighters or laborers for the Union army?15

Parke recognized his black soldiers’ accomplishments when he reported to his superiors that their conduct, with only a few exceptions, deserved praise. He was concerned about the “new material,” as they hurt the efficiency of his troops. They needed drilling and discipline, especially the conscripts and substitutes arriving in Petersburg. Parke also complained about the growing number of bounty jumpers. By the third year of the war an increasing number of blacks had joined for the financial rewards, especially since draftees could no longer pay a $300 commutation fee to avoid service. Substitutes could therefore demand higher payment, many of whom “skedaddled” not long after reaching the front.16

The Delaware Gazette reported in September that 300 more men left the black soldiers’ training camp for Petersburg. Successful recruiting in Ohio made the 27th USCT an overmanned regiment, even if some of the “new material” proved less than desirable. Unlike many of the black companies in the Army of the Potomac that had lost a significant number of men from both battle casualties and illness, the 27th had suffered comparatively little. Therefore, the extra men coming from the state had to be shared. The 4th USCT, which had over 1,000 men when it left Maryland in September 1863, had been reduced to just over 300 when state leaders employed recruitment brokers to help fill its ranks. The brokers sent 196 Ohioans to the 4th in August. On September 7 Charles W. Foster, chief of the Bureau of Colored Troops, wrote to the superintendent of volunteer recruiting services in Columbus that because both the 5th and 27th USCT regiments had full numbers, future black Ohioans who volunteered, substituted, or were drafted must be sent to the 16th, 17th, or 44rd USCT. To the relief of state government officials, Ohio could continue to count the numbers toward their quotas.17

On September 20 Foster informed Parke that the commanding officer of the 27th had reported to the War Department that his regiment had 1,100 men. Even though 250 of those were absent due to illness or battle injuries, the numbers still exceeded regulation. As a result, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton issued orders that 95 of the extra soldiers be transferred to the 23rd USCT of the 2nd Brigade. The 23rd, raised largely from the Baltimore and Washington, D.C., area, had seen more active duty than the 27th and had participated in heavy skirmishes in late May and early June while the rest of the black division guarded the supply trains. Consequently, the regiment had lost a significant number of men. Between October 17 and 20, 75 soldiers left the 27th. Albert M. Blackman and his officers carefully selected the transfers to ensure that the regiment sent mostly suspect recruits. Of the men, 31 were substitutes or draftees, and 60 percent of those reassigned had joined the regiment between July and September.18

Foster’s attention to rearranging and filling regiments came as part of his work to complete his annual statement on the USCT for the adjutant general of the U.S. Army. Foster noted that in his last report on October 31, 1863, there had been only 58 black regiments with 37,707 men. A year later, the USCT had grown to 140 regiments and 101,950 men. Ohio blacks made a significant contribution to the increase when the state raised its second regiment, the 27th, by filling the 5th, and by helping other regiments refill their ranks. Foster also reported that from the time the U.S. Bureau of Colored Troops began recruitment until October 20, 1864, losses by battle, disease, and desertion totaled 33,139. Although the 27th had lost just over 100 men by that date, they had fared significantly better than the overall USCT total.19 But another fight was already in their future, one that would place the soldiers in the Ohio regiment back on the battlefield and in the line of fire once again.

As an Indian summer blessed the Virginia countryside, Grant planned for the new offensive. He had grown increasingly uneasy about his failure to capture Richmond. Lincoln’s reelection bid was only weeks away, and the Northern population demanded another victory. Grant listened when Meade shared his ideas concerning the Southern defenses constructed between Hatcher’s Run and the fields south of Boydton Plank Road. In late October Meade learned that the newly manned Confederate lines were weak, and he believed that if he pushed hard enough his troops could break through near the road and make it to the Southside Railroad. Grant agreed and planned another joint movement by the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the James to flank both ends of Confederate defenses extending from Richmond to southwest of Petersburg. He instructed Meade to create a new line of defense stretching from Peebles’ Farm to the railroad. Meade was to leave enough men to protect the present lines but take over forty thousand troops from the II, V, and IX Corps and David M. Gregg’s cavalry to gain the new ground. Meanwhile, Grant directed Butler to keep Robert E. Lee busy north of the James River near Bermuda Hundred. When Meade told John G. Parke to prepare for the offensive, he instructed the commander to leave the 2nd Division of his 1st Brigade in the Union trenches. The 27th, with the 3rd, would once again take the battlefield.20

By late October rumors of another big movement had traveled across the camps and through the picket lines. On October 23 the men lined up for their inspection of arms. The next day, under the turning leaves of autumn, the officers drilled their troops. The events were so similar to the time leading up to the Crater it was easy to grow excited or nervous from all the talk. By the evening of October 25 it was no longer a question, as the IX Corps received their instructions to prepare for a march in the morning. The men obtained rations for six days and collected two hundred rounds of ammunition each. At 2:00 A.M. officers called their men to the ready, and within an hour the soldiers had packed their tents and were waiting for the order to move out. The 27th watched as the II and V Corps marched past. The inexperience of the new men showed as they claimed that the rebels would run before the black infantry arrived. Meanwhile, the soldiers who survived the mine debacle wrote letters to loved ones and made arrangements for their possessions. At 3:30 A.M. on October 27, orders came for the IX to move, and it was a cold and rainy morning when the men fell into ranks behind the 1st Division and marched down the road to join the Army of the Potomac several miles away.21

The black soldiers of the 1st Brigade of the 3rd Division faced their second battle with a new commanding officer, as Col. Joshua K. Siegfried had resigned from service. Col. Delevan Bates, senior officer of the 30th USCT, took command of their brigade on October 11 after recuperating from the injury he had received at the Crater. The twenty-four-year-old New Yorker was a survivor of Little Round Top at Gettysburg, Libby Prison, and the mine disaster. He did not want the responsibility of so many men, especially if they had to go into a fight. But now in late October he found himself in just that position. For the 27th, this meant three new officers leading them into their second battle, as the other two, Colonel Blackman and Lieutenant Colonel Donnellan had not been with the Ohio regiment at the Crater. While individually the leaders had military experience, Bates, Blackman, and Donnellan had not trained together, and Blackman and Donnellan had little time to develop any rapport with their black soldiers. Yet on they marched toward the enemy.22

It was dark and gloomy when Parke’s IX Corps advanced toward the Southside Railroad. The narrow roads made travel slow and difficult, as the rain turned the paths into rivers of mud. It was almost impossible to keep the movement a surprise as planned, and soon rebel scouts reported the massive Union operation to their commanding officers. Nonetheless, Parke continued with his orders. Meade sent the IX to strike enemy lines near Boydton Plank Road, the location he believed to be the weakest. The soldiers marched south from Peebles’ Farm and then west on Boydton Plank Road. Parke directed Edward Ferrero to place the 27th and 1st Brigade to the right of Orlando B. Willcox’s 1st Division. They would confront the Confederates near Poplar Springs Church just north of Hatcher’s Run Creek. Robert B. Potter’s 2nd Division took up the position right of Ferrero and extended the new lines to the Union entrenchments south of Petersburg.23

Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock prepared to push two divisions of the II Corps over Hatcher’s Run Creek further south near Vaughn Road. After fording the waterway, Hancock planned to proceed down Dabney’s Mill Road to flank the enemy near Boydon Plank Road. Warren’s V Corps was entrenched between Hancock and Parke near Duncan Road and the creek, with orders to support the IX if they broke through the Confederate lines or to back up Hancock’s men if not.24

Soon after the engagement commenced, the 27th and the 3rd Division advanced toward the supposedly weak enemy lines. They had to travel almost a half mile through dense woods, and the underbrush, briars, and downed trees ripped their clothing and scratched their skin. Once they made it through the forested area, they came within a hundred yards of the enemy line of works when Confederate abatis and entrenchments prevented their further advance. Delevan Bates ordered his men to quickly build protective works, as he realized that if attacked they would not be able to make a fast or orderly retreat. The soldiers, under enemy fire, collected anything they could find to build breastworks and create some type of protection along the line.25

Bates had his men probe the Confederate defenses along Boydton Plank Road to locate the best place to break through. After several skirmishes, officers had their men form a line of battle and move into the dense forest. To their surprise, they found the rebels well dug in and heavily manned. Through the trees came solid shot and exploding shells, although initially most went over the black soldiers’ heads. But it did not take long for the rebels to readjust their aim. As Blackman led his soldiers into the fray, a spent shell knocked him off his horse, fracturing a rib. Some of the men quickly moved their leader to the rear, where regimental surgeons Weld and Niedermeyer waited. Thirty minutes later, second-in-command John W. Donnellan received a more serious wound when hit in the right hip, and William F. Blanchard, one of the second lieutenants of Company F, felt a ball graze his left shoulder. Meanwhile, a bullet struck Com. Sgt. George L. Smith in the breast. Although stunned, the Bible in his pocket saved his life. Other soldiers were more seriously injured. Eighteen-year-old Orin D. Henry of Company E took a shot to the left side of his head and fell to the ground with a skull fracture. A bullet injured Cpl. James Whitfield of Company B in his left leg above his knee, separating the muscle from the bone. And nineteen-year-old Marion Robertson from Muskingum County, who had survived a gunshot wound to the head at the Crater, was hit on the right hand.26

When the news reached Parke that the enemy lines were too strong to break, he sent orders to fortify the line and hold the Union position until the II and V Corps turned the Confederate flank. That night, as the men worked to strengthen their breastworks, it began to rain. Without their tents, the soldiers had to sleep on the wet, open ground in the heavy downpours. They tried to find cover in the trees, but near midnight they heard the rebel yell. When some of the black troops broke for the rear of the lines. Pvt. Henry Clay used his musket to convince them to stay, yelling, “Stand to the works, boys, and we will lick the whole d(amn) rebel army!” After the slaughter at the Crater, the men had to muster all of their courage to hold their position. The soldiers from the Ohio regiment wanted to prove their bravery and ability to their white officers, and they did not want to disappoint the black community at home. It was also their opportunity to change the perceptions held by white Northerners who had heard the misrepresentations about the USCT actions at the mine assault on July 30. Fortunately, the threat quickly subsided and the Union held the ground all night.27

During the morning of October 28, the IX once again participated in minor skirmishes. The soldiers in the 27th believed that they would be sent on another advance when Parke ordered the black troops to move in force to the right of the enemy. But rebel fire proved too thick, and as a result the men had retreated by 12:30 P.M. Meanwhile, Warren’s troops failed to proceed, so command sent his V Corps to back up Hancock’s II Corps, which had experienced intense fighting and suffered heavy losses. The rains had made the roads almost impassable, so no reinforcements or resupply of ammunition could reach their defenses. Closer to Richmond, Maj. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel’s X Corps had also failed. Ulysses S. Grant, who was livid once again that he had received inaccurate information about the enemy, ordered a retreat.28 Neither the Union, nor Lincoln, could weather another disaster with the election so close.

The IX followed the II Corps on the retreat. The soldiers arrived in camp near Peebles’ Farm around one on Friday afternoon. As more rain fell in Virginia, officers counted their troops. The black 3rd Division had suffered from the engagements at the Battle of Boydton Plank Road, or First Hatcher’s Run. The 43rd bore twenty-eight of the division’s eighty casualties, and at least three of the nine officers dead or injured from the 3rd came from the 27th USCT. The regiment also lost fifteen men, including two soldiers killed and thirteen wounded. Pvt. Charles W. Butler’s untimely death proved to be one of the more difficult for Lt. George L. Gilbert to report. The inexperienced officer, who served the first part of the war in the Veteran Reserve Corps away from the battlefield, had just joined Company A. Gilbert wrote to his soldier’s wife, Martha, that Butler “was killed while on skirmish line axcidentially by our own men . . and in his death we have lost a good soldier.” Gilbert tried to comfort the Marietta widow when he assured her that the men had given her husband a proper burial. The casualty numbers shifted when on November 15 Alexander Chavous died from his battle wounds. The Logan County soldier had been shot in the chest.29

Most Ohioans received more favorable news. Quartermaster Nicholas A. Gray reported that the “sable soldiers of Uncle Sam” had gone into battle cheerfully, and that no one could question or criticize their performance. Albert M. Blackman, who would later receive a brevet to brigadier general for his “gallant and distinguished bravery” at Hatcher’s Run, said his officers “behaved splendidly,” and that other than the new recruits, his men “behaved excellently.” Gen. Ferrero reported that his officers and soldiers deserved “great praise” for their composure while carrying out orders. He specifically pointed out that he was “very much pleased with the conduct of the colored troops.” It redeemed the image of the 27th, tarnished by the events at the Crater. The men understood the value of the recognition, especially in light of the more successful black troops in Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s XVIII Corps. But the regiment was once again left without commanding officers as Blackman left for a twenty-day leave of absence and Lieutenant Colonel Donnellan remained in the hospital.30

Despite the favorable performance of the 27th and the other black troops in the IX Corps, Hatcher’s Run was another incomplete success for the Union. Unable to break through and cut off the Southside Railroad, Northern forces did extend their defensive lines westward and therefore further weakened the Confederate hold. But it would be the last major action along the Petersburg front in 1864, and with winter not far away, military operations slowed. The nights grew colder, and the leaves had already started to turn by the time the 27th rebuilt their camp. Soon the soldiers were, as one officer sarcastically remarked, “all comfortable again, enjoying the camp life.”31

In early November the IX Corps huddled along the lines near the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad, with the 3rd Division in the rear line of entrenchments between Fort Cummings and Fort Siebert. For the next several weeks, as an Indian summer blessed the men with temperate weather, the 27th spent most of the time on picket duty. Capt. Alexander S. Hempstead temporarily took charge of the regiment as Blackman and Donnellan recovered from their battle wounds. The twenty-six-year-old veteran from the 88th OVI reported, when preparing for the paymaster, that the condition of his men was “good.” But there were difficulties. At 4:00 A.M. on November 7, the 3rd Division prepared for a possible attack. They waited until nine that morning, but the enemy did not show. Tensions continued to increase, and friction grew between the officers and some of the men. When Lt. Charles Wilson ordered Pvt. James G. Gant of Company D to his tent in camp near Peebles’ Farm, Gant refused and retorted that he would not go unless he wanted to. It was not the first disciplinary issue for the private. On November 5 Capt. Frederick J. Bartlett had sent Gant to the commissary store for supplies, and the twenty-three-year-old barber had added a canteen of whiskey to Bartlett’s order. As a result of both infractions, Wilson drew up charges against Gant for disobedience of orders, disrespect for a superior officer, and conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline. Hempstead handled the matter by arranging for Gant to serve on detached duty with the Army of the James.32

Another problem for some of the white officers was the inability to complete all of their administrative duties. In early November Edward Ferrero asked for permission for his division to employ regimental clerks. He explained that his officers could not catch up on all of their paperwork. Ferrero complained that no one could “find a single man capable of acting as clerk” within their black regiments to act proficiently as noncommissioned officers. Not all white men who served in the USCT necessarily shared that sentiment about their black assistants, however. Although some regiments legitimately suffered from the lack of qualified soldiers, the 27th had a sufficient number of literate men. The problem was too few white officers. The roster of commissioned officers for the 27th listed only five of seven members of the field and staff, eight of nine captains, seven of ten first lieutenants, and six of eight second lieutenants present in November. And a significant number of men, who for a variety of reasons and despite the difficulty of approval, had attempted to resign their commands—and in the 27th one officer found himself removed from his position. In September, Capt. Joseph J. Wakefield had sought a furlough in order to assist his family, which was under duress due to his wife’s illness. In his request he had explained that no one in Clinton County would help her, as she was “surrounded by a class of people politically opposed to the war.” Later, when Wakefield failed to return to the regiment, Blackman sought a general court-martial, stating that Wakefield was absent without leave. The captain was found guilty and cashiered out of service. This did not bother his peers, who, as Lincoln supporters, knew that Wakefield planned to vote for Democrat and former Union general George B. McClellan in November when Ohio commissioners visited the camp to take the soldiers’ votes for the presidential election.33

Most black men did not have the privilege of voting in the 1864 presidential election. But Delaware County resident William Hannibal Thomas of the 5th USCT proudly cast his vote for Lincoln. As a result of the 1859 Ohio Supreme Court case, Alfred J. Anderson v. Thomas Millikin, et al., adult men who were of less than half African ancestry had the right to vote, which made it possible for some of the soldiers in the 27th and the 5th to cast their ballots. The African American newspaper correspondent to the Philadelphia Press, Thomas Morris Chester, reported on the polls held at Union camps in the Richmond area. It is unclear how he obtained the information, but he wrote that 194 soldiers from the 5th USCT voted for Lincoln. Other than the white officers of the black regiments in the 3rd Division, XVIII Corps, he provided no other information on USCT voting. Two soldiers from the 27th may have cast a ballot. In early November Levi Beer went to East Liverpool in Columbiana County to recover from the gunshot wounds to his right shoulder received at the Crater. Asst. Adj. Gen. H. H. Smith granted Beer’s furlough “to vote.” Thomas Cook, a private in Company I, received a furlough from Summit House Hospital in Philadelphia “to go to Ohio to vote.” At the morning inspection and dress parade on November 11, officers of the 27th USCT informed the men of the president’s reelection. The news, however, did little to change the soldiers’ present situation.34

As William T. Sherman made his way to the sea, Blackman returned to his command to find his troops suffering from the growing cold. To protect themselves from the bitter rain, snow, and dropping temperatures, the soldiers built huts of wood and mud, some with chimneys. The conditions in the pits caused great discomfort. Sgt. Charles W. Taylor of Company H had to be hospitalized for frostbite to his feet, a condition that meant the forty-three-year-old would not return to duty. But no matter how bad it seemed, the black soldiers understood that the rebels just over the lines had it worse. Throughout the rest of the month the 27th struggled with the elements, homesickness, and fatigue along the Petersburg front. Then rumors began to circulate about another major offensive, one that would include the USCT.35

Meanwhile, the regiment became part of a historic military experiment. In mid-November Grant decided to reorganize his Army of the Potomac. He announced that he would combine the white soldiers of the X and XVIII Corps into one and that all blacks in the Department of Virginia and the Department of North Carolina would move to a separate corps under Butler. Back in August, Butler had proposed to have the black troops of the IX Corps transferred to his army after he heard that they were demoralized by the events surrounding the failed mine attempt on July 30. He asked Grant if he could exchange a group of inexperienced white recruits from Pennsylvania with George B. Meade for the USCT in the IX, and on November 26 the 27th and the 3rd Division officially joined the Army of the James. Four days later Butler created the XXIV Corps for his white troops and the XXV Corps for his black troops. When approved by the War Department on December 3, the XXV became the first corps in American history composed entirely of black men. Butler transferred Cincinnati native Maj. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel from the XVIII Corps to lead the XXV. The twenty-nine-year-old, who had graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1855, began the war as chief engineer of Butler’s staff in the Army of the Gulf. After commanding his own troops, in May 1864 he returned to Butler to serve as the chief engineer of the Army of the James. He had limited experience with the USCT, as he had just replaced Maj. Gen. Edward O. C. Ord as commander of the XVIII in September.36

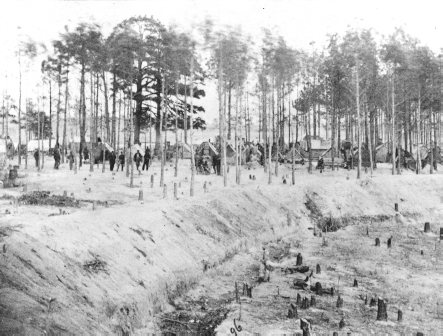

Fig. 12. Camp of the 27th United States Colored Troops along the Petersburg front in 1864. (Stereograph, Library of Congress)

At the end of November the 27th moved to Delevan Bates’s 1st Brigade in the 1st Division of Brig. Gen. Charles J. Paine, a Harvard-trained lawyer who had entered military service in 1861 as a captain in the 22nd Massachusetts. But these changes meant little to the men in the 27th USCT who suffered along the picket lines. When the presidential proclamation of Thanksgiving on November 24 provided the opportunity for a feast for some along the front, fortunate soldiers received chicken, turkey, fruit, and pies from the Soldiers’ Aid Societies. But the delicacies did not reach the Ohio regiment; the next day only apples arrived for them. Their disappointment compounded the difficult conditions faced by the regiment.37

Then the 27th moved to Point of Rocks on Saturday, November 26, and joined the Army of the James. They enjoyed warmer weather on the march but found themselves under constant rebel shelling. On Sunday the regiment moved near Bermuda Hundred, and over the next several days the Confederates intentionally targeted the black troops as they came and left for picket duty. On the morning of November 28 “the Rebs opened a galling fire upon” the picket line, and two days later the “Rebs” shelled all day. James E. Scott wrote to his mother that “our boys staid with them all day and we yet hold our lines and we in tend to hold our lines” and explained that they “lost some of our men who got wounded one was kild.” But he reassured her that the Union was making progress and that they would soon “brak up the Rebel nest and the Southern Confederacy.” On the evening of December 2 Butler ordered Union gunboats to target the enemy pickets to protect his new men. Scott wrote that he heard the “rebels yeld” but the “gun boat sure shut them up.” It also intensified the barrage of Southern bullets, so on Sunday, December 4, Butler had the black troops remove almost two miles to the rear of the Union lines. Once again the men heard rumors of their possible participation in an upcoming battle.38

The officers held an inspection of troops the next morning. Instead of hearing orders concerning a military engagement, the 27th and their division received instructions to return to the likewise dangerous front-line picket duty. Then orders came at 6:00 P.M. for some of the USCT regiments in Paine’s 1st Division of the XXV Corps to tear down their camp. The order included Ohio’s other regiment, the 5th USCT. The soldiers left for a movement against Fort Fisher, the Confederate fortification in North Carolina that protected blockade runners when they arrived from the Atlantic Ocean, while the men from the 27th remained in the trenches. That month the regiment lost at least five men. On December 3 two men, George Anderson and Gould Berry from Company D, supposedly deserted, and on December 9 a Confederate picket hit Wilson Gillard in the chest, killing the eighteen-year-old farmer from Miami County. Two days before Gillard’s death, nineteen-year-old Henry Price became separated from his comrades. He rejoined them on January 2, but it is unclear where he had spent the time in between. Then, on December 15, Wallace S. Smith, who had just joined the regiment in September, disappeared. Although possible, it seems improbable that Smith and the men from Company D, Anderson and Berry, would have considered it an opportune time to desert the Union lines. But the three were never heard from again.39

As winter set in, activity along the Virginia front slowed. The 27th remained on picket duty and watched as Confederate soldiers in the opposing trenches deserted. James Scott reported that as many as thirty men a day crossed into Union lines. He wrote home that he called one Southerner “johney and he cald me yank.” Meanwhile, several of the officers sought release from their duties. Lt. Charles A. Beery of Company A resigned after he received a surgeon’s certificate of disability; surgeon Francis M. Weld determined that the lieutenant’s case of syphilis, contracted before the war, had incapacitated the officer and made him unfit for duty. And the miserable captain of Company G, Albert Rogall, left the 27th after he received a hard-fought-for promotion to lieutenant colonel of the 118th USCT.40

On December 10 Albert M. Blackman forwarded his recommendation that Lt. Daniel M. Miner be promoted to captain to replace Rogall and suggested that George L. Gilbert take the place of Miner. Blackman explained that while there were others who had seniority, they had all applied for disability discharges, so he suggested that Gilbert be promoted to first lieutenant. Four days later, Blackman wrote to Brig. Gen. Lorenzo Thomas to acknowledge and accept his own appointment as brevet brigadier general, based on his “gallant and distinguished bravery” at Hatcher’s Run, and signed his Oath of Office certificate. On December 17 Blackman approved a request written by Capt. Sanders M. Huyek to Charles W. Foster to promote William F. Blanchard to first lieutenant to replace Beery. Huyek also asked Foster to assign two new second lieutenants, one to replace Blanchard and one to fill a vacancy. The captain was not the only officer in the regiment performing duties that should have been handled by the newly promoted Blackman.41

William F. Blanchard had been acting as commander of Company F since September as a second lieutenant, so Huyek’s request had merit. But Blanchard apparently had not received much support from the field and staff during that time, because on December 24 he sent a request to the paymaster to explain how and when he should apply clothing charges to the men in his company. At some point his frustration, along with the discontent of 1st Lt. Daniel J. Miner and 2nd Lt. George L. Gilbert, came to the attention of Benjamin Butler, and by the end of the month Butler had recommended all three for promotions and transfer to other USCT regiments. The loss of three more officers would weaken the command already dealing with declining numbers. During the month, only three of seven of the field and staff, six of the nine first lieutenants, and seven of the eight second lieutenants were present in the 27th USCT. Although the roster of commissioned officers listed all eight captains present, which failed to reflect Rogall’s exit, the overall number of officers had dropped from thirty-four in November to thirty-two.42

Meanwhile, Benjamin F. Butler’s days with the Army of the James were numbered. The attempt to take Fort Fisher had been a dismal failure. With the elections over, neither Grant nor Lincoln had to deal with political ramifications surrounding Butler’s military appointment. A messenger gave Butler the news on January 6, 1865, that Abraham Lincoln had relieved him from command of the Army of the James. Butler bade farewell to his troops on January 8, with specific comments directed to the black soldiers. He applauded their bravery, loyalty, and manhood, stating “With the bayonet you have unlocked the iron-barred gates of prejudice, opening new fields of freedom, liberty, and equality of rights to yourselves and your race forever.”43

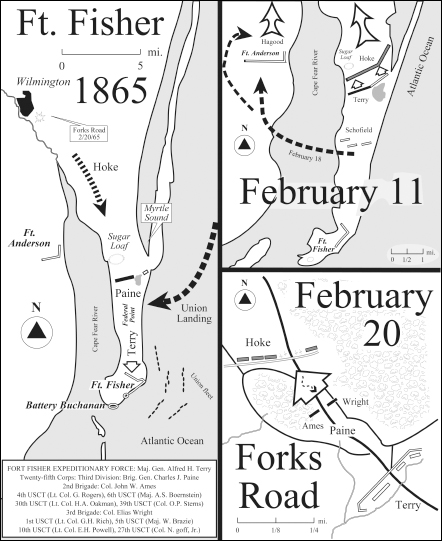

The men in the 27th USCT did not hear his accolades. The soldiers’ time with the all-black XXV Corps had come to an end. After the return of Paine’s regiments that had participated in Butler’s failed attack, command restructured the black divisions. The 27th first moved to the 3rd Division of the 3rd Brigade, but Grant soon detached them to Terry’s Provisional Army Corps in the Department of North Carolina. Butler’s farewell coincided with the Ohio regiment’s departure to participate in the Union’s second attempt to close down Fort Fisher, the last significant enemy port on the eastern seaboard at Wilmington, North Carolina.44

Wilmington, established in 1740, was the largest and most important seaport city in North Carolina. Three major railroads made it a vital Confederate depot, especially by 1864, when it provided crucial supplies for Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, entrenched along the Richmond and Petersburg lines. The city’s location, just over twenty miles up the Cape Fear River, provided a defensive position out of the Union navy’s reach. At least that is what the Southern government and 9,500 residents believed.45

Enemy forces could not protect the entire hundred miles of coastline, but Fort Fisher did an impressive job of guarding the inlet into Cape Fear River. The “Confederate Goliath” sat south of Wilmington on Federal Point, renamed Confederate Point in 1861. Earthworks on three sides protected the fort, built upon the narrow sand peninsula. Col. William Lamb and close to a thousand troops manned the seemingly impregnable fortification. Lincoln’s attempt to successfully blockade any goods coming in or going out of the South depended upon the capture of Fort Fisher, and Union control of the Wilmington area would also reduce the South’s ability to continue the war. The Northern command increased efforts to take the fort in the summer of 1864, when it became the last eastern port open to the Confederacy.46

Ulysses S. Grant moved quickly after the failed attempt in December to eliminate Wilmington’s ability to support the Confederacy. On January 2 he placed Maj. Gen. Alfred H. Terry, commander of the XXIV Corps, in charge of the operation. The Connecticut lawyer was not regular army, but he had both amphibious and combat experience from his service earlier in the war. More important, Grant knew that Terry would obediently follow orders and understand the importance of a cooperative joint effort. Adm. David D. Porter, who led the amphibious assault for a second time, preferred Terry to Benjamin F. Butler. But he expressed his displeasure that black troops would again participate in the mission to capture Fort Fisher. Although Porter blamed Butler for the failure, he also felt that the inexperienced soldiers who accompanied the expedition had contributed to the unsuccessful outcome. Grant wondered if his operation in North Carolina would again be threatened by problems between his commanders.47

Grant told Terry to prepare eight thousand troops for the upcoming movement, although he gave the officer little information. The soldiers came from Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames’s 2nd Division and Brig. Gen. Joseph C. Abbott’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the XXIV Corps, and Brig. Gen. Charles J. Paine’s black 3rd Division of the XXV Corps, including soldiers in Ohio’s 27th and 5th USCT. Rumors circulated that they would join William T. Sherman’s forces in the Carolinas, but Grant had spun the tale to confuse the enemy and kept the actual plans quiet. Grant also expanded the goals of the expedition. The first had been to take Fort Fisher and close the Cape Fear River to blockade runners. The new mission included both of these goals and the capture of Wilmington.48

The 27th left their snow-dusted camp near Chaffin’s Farm in Virginia on Tuesday, January 3, 1865. They carried four days’ rations and forty rounds of ammunition, but no personal effects, as they walked through the sleet toward Bermuda Hundred. They spent their last two nights along the Virginia front on frozen ground with no cover. The difficult march took a toll on the men, including Richard Hedgepath of Company K, who slumbered in pain the first night. Earlier in the day the forty-three-year-old from Athens County had injured his right knee and back when he tripped on a stump. On Thursday at 2:00 A.M. officers called the men to the ready. They marched to the James River, where they packed into transport vessels. Blackman and five of his companies boarded the steamboat Eliza Hancox, while the rest of the regiment departed on the steamer Idaho and the single-turreted monitor ironclad, the Montauk. At Fort Monroe Blackman and his men transferred to the Idaho, while Terry learned the details of the secretive expedition. At 4:00 A.M. on January 6 nineteen vessels embarked on the Union mission to capture Fort Fisher.49

Stormy conditions made their voyage an uncomfortable passage, one that frightened some of the men and angered others. Some of the soldiers yelled out vulgarities, others prayed, as gale winds slammed twenty-foot waves against the boats. Many of the men suffered from seasickness but received no medical care, as both of Dr. Francis M. Weld’s assistants, William C. Ross and Therrygood Manley, were seriously ill. After two days they reached Beaufort, North Carolina, but the men did not have the opportunity to disembark. The troops spent four long days on the ships awaiting orders. As the black soldiers attempted to deal with their physical discomforts and emotional anxieties, those who had participated in the failed first expedition wondered if they would suffer the same experience again.50

But this time events transpired as planned. On January 11 the weather abated, the seas calmed, and the fleet resupplied at the Morehead City Wharf with little trouble. The next day they unloaded the seriously ailing soldiers, and the contingency sailed to their rendezvous point with Admiral Porter, near New Inlet off of Federal Point. By the time they arrived it was too late to begin the operation, so Terry and Porter decided to let the men rest that night and begin the assault in the morning. When the sun came up over the Atlantic Ocean, Terry ordered his men to pack twelve days’ worth of rations and the ammunition they brought from camp.51

At dawn Porter’s fleet began to shell the Confederate fort. Better positioning allowed the Union to inflict the damage the first attempt in December had failed to do. The heavy bombardment made it difficult for the rebels to make repairs to the fortress, and enemy soldiers positioned behind Fort Fisher’s defensive walls could only watch as more than eighty naval warships and army vessels made their way closer to “the Confederate Goliath.”52

When Alfred H. Terry’s white troops disembarked at 8:45 A.M., the commander stressed the need for an orderly and swift movement onto the enemy’s beaches. By 10:00 A.M. the 27th USCT had joined the Union forces attempting to land on the Atlantic shore five miles north of Fort Fisher. It took over five hours to complete the mission, as surf boats placed on navy transports moved the men as close to shore as possible. Rough tides kept the boats from the shallow waters, and most of the soldiers and many of their officers became drenched in the process. The men covered two miles of beach as they unloaded supplies and entrenching tools under the protection of intense cannonading from their naval comrades, shells splashing in the water and on the beach around the men.53

The Union soldiers dried off while they waited for the sailors to bring fresh ammunition and rations. In the late afternoon Terry proceeded with his orders, leaving Joseph C. Abbott’s men on the beach to burn campfires in an attempt to misdirect Col. William Lamb’s attention. Terry moved out with Paine’s and Adelbert Ames’ troops. Their first goal was to build a line of defenses between the fort and Wilmington in order to protect their mission from Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke’s Confederate forces to the north. The 27th and the 3rd Division led the movement over marshes and sandy soil in the dark, cold, and rainy night, clearing the way for the rest of the troops as deafening cannon fire inflicted pain on and injury to their eardrums. It took hours for Terry to locate defensible ground, so it was 2:00 A.M. before they began to construct their breastworks. Meanwhile, Hoke and his men left the city at 1:00 A.M. and entrenched at Sugar Loaf, a fifty-foot-high sand dune northeast of Fort Fisher along the Cape Fear River and across from Fort Anderson, where they waited for orders to reinforce Lamb. By 8:00 A.M. the exhausted and bone-chilled Northern troops had completed their assignment. They had constructed a defensive line almost one mile across the peninsula between the ocean and the Cape Fear River.54

In the morning light the men located several homes that had been abandoned before their landing and helped themselves to food and household goods. A number of the black soldiers made sport of their find and put on the women’s clothing and danced for their tired comrades. After allowing the men to alleviate some tension, Terry called his troops to order. He ordered Ames to rest his soldiers for the upcoming attack and placed Paine’s USCT on picket duty in the newly constructed trenches. Porter continued his bombardment on the fort. The next day the 27th helped to prepare rifle pits and reinforce Union breastworks. That evening a full moon lit the sky above the Union forces as they held their position in the cold trenches north of Fort Fisher.55

On Sunday, January 15, the sun exposed tranquil seas to the poised Union forces. But the peaceful image soon ended. Just after 7:00 A.M. the largest fleet in United States history up to that time began another bombardment from the sea, pummeling the already crumbling fort. The ground shook from the cannonading as Paine’s black troops and Abbott’s division held the lines in the trenches only two and a half miles from Fort Fisher. Terry and Porter agreed to continue the bombardment until 3:00 P.M., when they would each send in troops for the land assault. Porter readied a group of 1,600 sailors and 350 marines to hit the sea face on the northeast side of the garrison, and Ames prepared his 2nd Division of the XXIV Corps, with Brig. Gen. N. Martin Curtis’s brigade in the lead, to attack the land face from the west. Lamb, the engineer responsible for the defenses at Fort Fisher, had provided little protection for the landside in his design, as he believed that any attack would come by sea.56

The naval forces went first, in part to distract the rebels from the major assault by Terry’s men. But the infantry failed to be in position in time, so many of the sailors and marines found themselves exposed to enemy fire. Finally, Ames signaled Porter that his men were ready. A dead quiet fell over the peninsula when the Union ships ceased their fire. Minutes later a steam whistle pierced the still, cold air, and at 3:25 P.M. the assault began. Within thirty minutes 4,000 infantry troops made it into the Southern fortress. The soldiers faced brutal hand-to-hand combat, but they fared better than the naval forces, which suffered high casualties and had to retreat.57

In the meantime Gen. Braxton Bragg, commander of the Confederate Department of North Carolina, belatedly sent two of Hoke’s brigades southward from Sugar Loaf to assist Lamb and his men. The 27th and their division held strong on the river side while white troops occupied the defenses near the ocean. Hoke, in charge of the Confederates who had massacred surrendered black soldiers at Plymouth, North Carolina, in April 1864, failed to break the line. Bragg ordered Hoke to withdraw his troops, hoping that the South Carolina men he had sent by sea could provide Lamb the support the fort commander had repeatedly requested.58

Confederates in the garrison remained steadfast in their determination to hold their position. When Gen. William H. C. Whiting, commander of the District of Wilmington, arrived at the fort, Lamb had only fifteen hundred men available. With the situation bleak, Lamb offered to turn over control, but Whiting reassured Lamb that he came only to assist, as both men knew their situation had a great deal to do with Bragg’s lack of support. With Hoke’s failure, they would have to do the best they could.59

By late afternoon Terry sent for Abbott’s brigade to back up Ames and ordered the battered naval troops to assist Paine’s men along the breastworks. He also ordered Paine to send “one of the strongest regiments” from the black division to accompany Abbott. Why Paine selected the 27th USCT is unclear, as other regiments had more battle experience and more officers present. But at 7:00 P.M. the Ohio regiment, the only black troops to participate in the final assault, prepared to join the fight. At the same time, Ames and Curtis disagreed over their troops’ progress and sent the general contradictory reports. Terry seriously contemplated digging in for a siege as the 27th answered his call to action.60

It was growing dark when the Union reinforcements reported to Ames. His men had already breached Fort Fisher but still faced great resistance. When Abbott arrived, Ames sent some of the white troops to assist Curtis in the fight while ordering the rest to help dig entrenchments. When the 27th attempted to reach the fort through a narrow causeway, heavy fire kept them at bay. Blackman told his to men to wait. As the 27th dropped to the ground, rebel shots fell all around them and exploding shells from their own navy flew over their heads, injuring at least four of the soldiers. Inside the walls, Terry’s men told the stubborn Confederates to surrender or they would bring in the black soldiers and allow the USCT to take out their wrath on the trapped rebels. But Terry told Blackman to remove his troops and await further orders. At around 9:45 P.M. command sent the 27th back to the fort, but when the men arrived they found that it had been evacuated. An eerie quiet fell over the fortress as the naval bombardment ceased. The soldiers could hear the water ripple over the bodies of the dead and the cries of the wounded nearby. It looked as though they had missed the fight.61

Union forces captured over twelve hundred rebels when the fortress fell just after 9:00 P.M. on January 15. Several hundred escaped, though, including injured officers Lamb and Whiting, who were carried out on stretchers by their men as the Northern troops took the fort. The Confederate major James Reilly sent the escaped soldiers to Battery Buchanan, a small fort on the southernmost tip of Federal Point. He hoped that forces there would provide cover until they could evacuate over the river, but the Southerners had already abandoned the fortification. Terry sent Abbott’s 7th New Hampshire and 6th Connecticut along with the 27th USCT in pursuit.62

As colorful signal flares filled the skies like fireworks, Blackman and his Ohio regiment marched behind Abbott’s troops on the beach behind the sea-face wall of the defeated fort. The men stopped at Mound Battery, just south of Fort Fisher, where surrendering rebels told Abbott and Blackman that their commanding officers and a group of soldiers were heading toward Battery Buchanan. Abbot took his men to the right, and the 27th moved to the left along the beach and formed a line for battle. Blackman sent a detachment of six men under the command of Adj. Albert G. Jones to circle around the battery. Stunned Confederates, who found retreat impossible, watched in the bright moonlight as General Whiting asked, “To whom have I the honor of surrendering with my forces?” Jones said, “To General Blackman, of the 27th United States Colored Troops.” Whiting’s chief-of-staff, Maj. James H. Hill, then surrendered to Jones. Shortly thereafter, Blackman arrived to find his men holding Whiting and Lamb, both wounded, and took control. Maj. James Reilly surrendered to Abbott’s troops coming from the opposite direction. Just before 11:00 P.M., Terry arrived and received the official surrender from Colonel Lamb and General Whiting. Terry hurried away on horseback to send the news to Grant and left Blackman in charge of Battery Buchanan.63

Meanwhile, the 27th USCT placed over 500 Southerners under guard. Jones later recalled how “the very thought of surrendering to colored troops was like gall and wormwood to them; but such was the fate of war, and the master was compelled to march behind the bayonet held in the hands of a former slave.” Surgeon Francis M. Weld recorded in his diary that night how in the bright moonlight Whiting and 650 men surrendered to Jones. Some of the soldiers were disappointed that they had to miss “the fun of shooting” the rebels. They were the only black troops to participate in the charge of the fort, and even though they did not face battle, they helped to constrict the power of the withering Confederacy. After nine months of limited opportunities on the battlefield and unlimited fatigue duty, the 27th USCT played a noteworthy role in a significant Union victory. Finally, they had experienced glory as United States soldiers. But the next day the excitement gave way to more mundane soldierly duties, Blackman keeping part of his regiment at Buchanan and sending others to help at Fort Fisher.64

Many of the Northern troops were too excited to sleep after the events. Some scoured the grounds looking for souvenirs and food, while others located alcohol. Unfortunately, negligence by some of the explorers led to a costly accident the morning after the Union victory when, at 7:30 A.M. on January 16, open flames near a magazine ignited unspent ammunition. The Richmond Daily Dispatch reported that the “carelessness of some of the colored troops” caused thirteen thousand pounds of powder to explode when the Yankees carried candles into the storage facility. Smoke, sand, and rubble flew over five hundred feet into the air, and as soldiers desperately searched for casualties, it took almost five minutes for the dust to settle. Some of the men were buried in the destruction and suffocated before they could be rescued. Matthew Hill, who had run from Fort Buchanan to see what had happened, helped locate a comrade from Company H, William H. Steptoe. The twenty-eight-year-old drafted farmer from Pickaway County, who had received a minor gunshot wound at the Crater, was trapped in the debris and had been blinded by the blast. Another man, Henry Price, who had just returned to the regiment only days before the soldiers left Virginia, was killed. Terry reported that the explosion caused 130 additional Union casualties, while others indicated closer to 200 injuries and deaths among the Northern soldiers.65

Injured soldiers on Federal Point suffered terribly in the days following the attack. The men had arrived on the peninsula with no personal baggage or tents, and medical supplies remained on the transport ships. It took naval personnel until January 20 to remove the wounded. The battle and munitions explosion led to over 670 Union casualties. The 27th lost one man killed and at least five wounded, although exposure during the following weeks led to the deaths of at least a dozen more. The Confederates lost 500, or 25 percent of their forces, and the balance became prisoners of war.66

Northerners lavished praise on the expedition. Grant ordered a hundred-gun salute, and on January 26 Congress and Lincoln issued a resolution thanking Alfred H. Terry, his officers, and his men for “unsurpassed gallantry and skill.” In turn, Terry applauded Paine’s USCT for successfully holding their defensive position, calling their contribution “a work absolutely essential to our success.” Terry singled out the 27th, thanking Blackman for the swift and successful action taken to pursue the enemy, but he neglected to recognize the Ohio regiment’s role in capturing the fleeing Confederate commanders. Quartermaster Nicholas A. Gray told readers of the Cleveland Morning Leader that he supposed they had already read about the Union victory at Fort Fisher, but he wanted to inform them about “the specific part taken by the ‘Buckeye Black Boys’ and their field and line leaders.” Ross County readers of the Scioto Gazette also learned of the role played by local black soldiers who had protected the breastworks, but the 27th’s role at Battery Buchanan did not make the report on the Union’s “glorious victory.” Capt. Elliott F. Grabill of the 5th USCT predicted that despite the “essential part” played by the black soldiers in the campaign, they would not be recognized for their contributions. The Oberlin College student believed that because the USCT “worked with spade and shovel” they would be overlooked and that “the white troops who did the fighting will get the praise.” In the end, it was Terry who received the reward. When Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton arrived at Fort Fisher on January 16, he ceremoniously promoted Terry to brigadier general on the field, making him the only volunteer officer to obtain the rank during the war.67

The 27th guarded Battery Buchanan until January 19, when the 4th New Hampshire replaced them. The soldiers did not return to the Army of the James or the Richmond front. They remained detached from the XXV Corps and served under Paine at Fort Fisher. Blackman and his troops rejoined the black division positioned in defenses north of Fort Fisher as Adelbert Ames’s and Joseph C. Abbott’s white troops participated in reconnaissance missions to determine the rebel strength protecting Wilmington. The Confederates blew up Fort Caswell and Fort Campbell as they moved closer to Wilmington, and after attempting to hold Fort Anderson, they entrenched at Sugar Loaf, where for the remainder of January a stalemate developed between Terry’s troops and Hoke’s forces.68

The excitement and pride of playing a key role in the capture of Fort Fisher faded as the daily requirements of military life became more difficult along the Cape Fear coast. Conditions deteriorated rapidly, and the number of sick multiplied. The men endured foul winter weather, “cold as Greenland,” along the coast. The rain and sleet made rest almost impossible as the black soldiers waited for their tents and personal baggage to arrive from Virginia. They suffered from their diet as well; the men lived on rebel hardtack “worms and all.” Yet their work as soldiers continued. The 27th helped to repair Fort Fisher, built wharves for supply ships and bombproofs along the Cape Fear River across from Fort Anderson, and continued to do picket duty.69

Overall, the Northern forces felt optimistic that they would soon capture Wilmington and that the end of the war would follow. On January 28 Grant visited Adm. David D. Porter and Terry to explain how he expected his troops to capture Wilmington. A few days later, Lincoln and his secretary of state, William H. Seward, met Vice President Alexander Stephens and two other Confederate officials at the Hampton Roads Peace Conference, but Lincoln refused to accept peace terms that recognized Southern independence and returned to Washington. As a result, Grant proceeded with his plans. He sent Brig. Gen. John M. Schofield, commander of the XXIII Corps, to lead the operations. Schofield arrived at Federal Point on February 8 to take command of the Department of North Carolina. He brought along Ohioan Maj. Gen. Jacob D. Cox, commander of the corps’s Third Division, to assist Terry’s forces. Grant directed Schofield to capture Wilmington, then move toward Goldsboro to resupply and support William T. Sherman. The next day, Terry’s command, including the 27th USCT, transferred to the Department of North Carolina.70

As army officials planned their next move and the black soldiers toiled in miserable conditions, Blackman sought a higher position than his command of the 27th. While stationed on guard duty at Fort Buchanan, Blackman wrote to Brig. Gen. Lorenzo Thomas on January 18, requesting that he “be assigned to command by virtue of my rank as Brigadier General of Volunteers by Brevet.” That same night some sort of “unpleasant occurrence” led Blackman to send his resignation to Terry. The major general refused to accept Blackman’s offer and on January 22 approved his request to receive a higher command. Five days later Blackman thanked his commander on behalf of his officers for “the satisfactory manner” in which Terry had explained the cause of the incidence and assured him that the communication had “restored all to their former good feeling.” Blackman also rescinded his resignation.71

It is unclear what happened the evening before the 27th was relieved from guard duty at Fort Buchanan, but it may have had something to do with reports filed by Terry’s other officers. In the least, the event would have pushed an already aggravated Blackman, who was probably aware that the commanders had neglected to recognize the role that the black regiment played in the Confederate surrender at Battery Buchanan. Brig. Gen. Joseph C. Abbott’s January 17 official report failed to mention the 27th at all and also claimed that he was offered the surrender but made the Southerners wait for Terry. Brig. Gen. Charles J. Paine stated that he sent Blackman and the “Twenty-seventh Regiment” to comply with orders for additional troops and noted that the “Twenty-seventh Regiment” was the only one from the 3rd Brigade that failed to report to him or return to position after the surrender. Understandably, Maj. Gen. William H. C. Whiting left out the role of the 27th USCT when he detailed his surrender to Confederate officials. And it is unclear why, but unlike the other accounts, Terry’s final report dated January 25 did acknowledge Blackman and the black regiment from Ohio. He stated that the 27th, with Abbott’s men, had been “pushed down the point to Battery Buchanan,” where “all of the enemy who had not been previously captured were made prisoners.” Terry avoided any specific reference to the Confederate officers’ surrender but in his conclusion noted that “better soldiers never fought” and commended Blackman for his “prompt manner.”72

This minimized recognition had a potentially negative impact on both the white officers and the black soldiers of the 27th USCT. In the mid-nineteenth century, evidence of a soldier’s bravery and contributions to battle victories had great importance to the characterization of one’s manhood. Additionally, it confirmed that a man was a virtuous citizen and provided community and state pride. The July fiasco at the Crater and the explosion at the fort the day after the surrender, which were both blamed on black troops and their commanders, made recognition of the 27th’s participation at Fort Fisher all the more critical. Therefore it is possible that Blackman’s attempted resignation was a result of Terry’s lukewarm acknowledgment of the regiment’s role, or at least his leadership, in the Union’s much-needed victory in January 1865.

But the problem may also have been caused by issues unrelated to the regiment’s role at Fort Fisher. On January 18, the same day that Blackman attempted to resign, confirmation by direction of the president appointed the three officers recommended by Benjamin Butler in late December to other regiments. The three men accepted their promotions only days before leaving Virginia, and by the time official word of the promotions reached Blackman, Daniel J. Miner was already serving as a captain with the 23rd USCT. Other officers were also a problem for Blackman. The same day that he thanked Terry for his support over the “unpleasant occurrence,” Blackman placed Lt. James W. Shuffelton of Company E under arrest for disobeying orders. Blackman’s temperamental mood was no doubt exacerbated by his own professional and personal frustrations. Despite of, or due to, his practice of placing much of his administrative responsibilities on his officers, the regimental paperwork from 1864 had not been completed. And his responsibilities in Ohio weighed on him. Blackman’s family was in distress. Catherine Blackman had had to care for their family before, when in 1859 her husband attended Rush Medical College in Chicago. But since 1861 she had been on her own with several children under the age of five for much longer periods, and she had become overwhelmed after the death of her mother and having to deal with her son’s spinal affliction.73

Regardless of Blackman’s problems, the Union army moved to take Wilmington. On February 10 Schofield sent the orders to his command, and at 9:00 A.M. the next day Porter’s naval forces bombarded Fort Anderson, which was located fifteen miles south of Wilmington on the west bank of the Cape Fear River. Half an hour later Terry’s troops, including the 27th, marched northward along the Cape Fear River toward Sugar Loaf. After almost two miles, they encountered rebel picket lines. Although it was Paine’s 2nd Brigade that charged the enemy works, the black soldiers in reserve still encountered heavy fire. James E. Scott, now a corporal of Company H, watched as several more of his comrades fell to rebel shot. Ross County native Sgt. Qualls Tibbs of Company E took a bullet to the right shoulder, and nineteen-year-old Thomas J. Brewer of Company D, who served as regimental musician and hospital attendant before the Fort Fisher campaign, received a serious injury to his right thigh. It was during this encounter that many of Schofield’s men witnessed black soldiers in action for the first time. Ohioan Maj. Gen. Jacob D. Cox, for instance, described them as disciplined and solid in battle. When a New York Times reporter wrote an account of the battle, he expressed admiration for the USCT. In the fight, which lasted until 4:00 P.M., the federals lost 128 killed and wounded, including 6 soldiers from the 27th, but they could not dislodge the Confederates. So Terry ordered his troops to dig in, and that evening they built new entrenchments approximately a thousand yards from the enemy lines, although in some places it was reported to be as close as three hundred yards.74 The next day, some of Terry’s white brigades attempted to flank Robert F. Hoke’s men by traveling northward along the ocean beaches. The 27th and the other black soldiers remained in the trenches to hold the Union position. Inclement weather made the operation too difficult, however, and the troops had to retreat. Rain that began late on February 12 continued for the next several days. On the 15th a downpour drenching the men, who had suffered continually from exposure since their arrival in North Carolina almost a month earlier.75

Fig. 14. Sgt. Qualls Tibbs served in Company E of the 27th United States Colored Troops from February 1864 to May 1865, when he received a disability discharge. He was wounded on February 11, 1865, when the regiment engaged the enemy at Sugar Loaf in North Carolina. Ambrotype, Camp Delaware, Ohio, 1864–1865. Silver nitrate on glass photographic plate. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2011.4.2).

Fig. 15. Front (top) and back (bottom) of a brass identification tag for Sgt. Qualls Tibbs of the 27th United States Colored Troops. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2011.4.6)

Two days later, Terry ordered the men to gather three days’ rations and sixty rounds of ammunition. After Union successes at Fort Caswell and Smith’s Island, the Northern command was determined to take Fort Anderson. Rebel picket fire from the fort, which had begun to intensify during the previous week, injured a number of Schofield’s soldiers. Once again, Porter’s ships hit first. As Adelbert Ames’s division attempted to flank the enemy at Fort Anderson, the black troops participated in two charges against Hoke in an attempt to keep him from sending reinforcements across the river.76

On Wednesday, February 18, Jacob D. Cox’s troops joined the assault on the fortress as Terry’s men renewed their attack on Hoke’s forces at Sugar Loaf. As part of the Union advance, the 27th and the other black regiments came up to the enemy’s rear guard and engaged the rebels in skirmishes most of the day. The 27th had weakened considerably since arriving in North Carolina. Walker D. Evans, for one, had succumbed to illness the day before, and Company B was already undermanned, as twenty-three other soldiers were unfit for duty. Evan’s death weighed heavily on the now captain Edward F. McMurphy; the thirty-eight-year-old from Union County had served as McMurphy’s sergeant for over a year. Fortunately, the fighting did not intensify, and by late evening the Confederates had abandoned their lines. The next day the 1st, 5th, and 27th USCT all suffered casualties in an attempt to follow the retreating Confederates, who had also abandoned the fort. Union forces on both sides of the river moved into their enemy’s trenches to prepare for a final push into Wilmington, naval and army cooperation proving successful again. But they were not finished.77

After a short rest, Terry ordered Col. Elias Wright’s 3rd Brigade, including the 27th, to pursue Hoke along Telegraph Road. Lt. John R. Myrick’s 3rd United States, Battery E, and Ames’s Second Brigade followed as Abbott’s men traveled up Myrtle Sound. Meanwhile, Cox led Union forces west of Cape Fear to within three miles of Wilmington, where they encountered resistance at Town Creek. Instead of advancing, Schofield had Cox bring his men back across the river to follow Paine’s troops. With the 5th USCT in the front, the soldiers marched unopposed until February 20. That day they stopped to rest halfway between Sugar Loaf and Wilmington. At 3:00 P.M. Wright sent the 5th USCT into a skirmish about five miles out of the city. Unable to advance, the men entrenched. Paine placed the black soldiers in the front line while his white troops built defenses about one half mile to the rear. Over the next thirty-six hours the Ohio regiments came under enemy sharpshooting, and although this proved costly for the USCT, their white comrades recognized their valor and success in the role as fighters instead of laborers.78

As the detached troops participated in the Wilmington campaign, their commander in Virginia awarded the XXV Corps square patches for the black soldiers’ uniforms. Maj. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel declared that the men deserved to wear the badges as a symbol of equal rights “hitherto denied.” He applauded their contribution to the destruction of “the prejudice of the world” and praised the “peace, union, and glory” they gave to the “land of their birth.” The black soldiers in the 27th were not there to receive the accolades or the fabric patch that left some of their officers unimpressed. Instead, they were busy defending the new lines of entrenchments north of Federal Point.79