Trees are almost everywhere. They are planted along streets and around playgrounds. They create pleasant, cool, shaded areas around homes in the summer. Trees provide food, shelter, and homes for birds and other wildlife. City parks and gardens are valued for their beautiful trees, and forests are enjoyed by hikers, naturalists, campers, and bird-watchers.

Trees—and shrubs—are large plants with hard woody trunks or stems. Most have leafy branches or groups of leaves. Size is generally the best way to tell the difference. Shrubs usually grow less than 15 or 20 feet tall and often spread out close to the ground. A mature (fully grown) tree can grow tall and straight to a height well over 20 feet.

Most trees have a single main trunk that branches out into many smaller branches and twigs. But most shrubs have several woody stems rising right from the ground and then dividing into thinner branches. Your school, house, apartment, or nearby grocery store parking lot probably has several shrubs planted around it.

Here are some examples of shrubs:

flowering lilac

flowering lilac

blueberry bushes

blueberry bushes

azaleas

azaleas

honeysuckle bushes

honeysuckle bushes

flowering forsythia

flowering forsythia

others: hawthorn trees, witch hazels, and sumacs can often grow more than 15 feet tall, so they are described in field guides as small trees or large shrubs. A single plant family can include both trees and shrubs—and even small woodland wildflowers!

others: hawthorn trees, witch hazels, and sumacs can often grow more than 15 feet tall, so they are described in field guides as small trees or large shrubs. A single plant family can include both trees and shrubs—and even small woodland wildflowers!

This large silver maple, planted as a shade tree, is about 40 feet tall.

Hawthorns are often described as shrubs or small trees, because they usually grow less than 20 feet tall. This downy hawthorn is in full bloom and about 12 feet tall.

It can be confusing to tell a tree from a shrub. Some trees don’t grow tall because they are stunted by insect damage or poor growing conditions, such as drought. And many trees are pruned and trimmed so that they remain small. Even though they could become much taller, they are kept to the size of a shrub (less than 20 feet tall). Here are a few examples:

Apple trees can grow more than 20 feet tall, but in orchards they are usually pruned and trimmed to keep them smaller to make it easy to harvest ripe apples from them.

Apple trees can grow more than 20 feet tall, but in orchards they are usually pruned and trimmed to keep them smaller to make it easy to harvest ripe apples from them.

Rhododendrons can grow well over 20 feet high in the wild, but when planted in front of houses or public buildings they are kept trimmed to stay small.

Rhododendrons can grow well over 20 feet high in the wild, but when planted in front of houses or public buildings they are kept trimmed to stay small.

Hemlock trees growing naturally in the wild can grow 60 to 70 feet tall—with some huge specimens reaching more than 100 feet! But they are sometimes planted in rows near a building and trimmed and pruned to form a low hedge.

Hemlock trees growing naturally in the wild can grow 60 to 70 feet tall—with some huge specimens reaching more than 100 feet! But they are sometimes planted in rows near a building and trimmed and pruned to form a low hedge.

A balsam fir can grow to be a large tree—usually 50 to 60 feet tall. But on a tree farm where Christmas trees are raised and grown, they are trimmed so they can fit inside a house for the holidays. Balsam firs in poor growing conditions may only grow a few feet tall.

A balsam fir can grow to be a large tree—usually 50 to 60 feet tall. But on a tree farm where Christmas trees are raised and grown, they are trimmed so they can fit inside a house for the holidays. Balsam firs in poor growing conditions may only grow a few feet tall.

On the coast of Newfoundland, Canada, balsam firs are stunted and windblown. Even though they are mature trees, they can’t grow very tall. Groups of these stunted, low trees are called tuckamore. The tuckamore firs shown here are only about four feet tall.

Rhododendrons are often used for landscaping in front of homes and public buildings. This “rhody” is kept pruned to maintain its shape and size. Several different species (and cultivated varieties) are grown and used for planting.

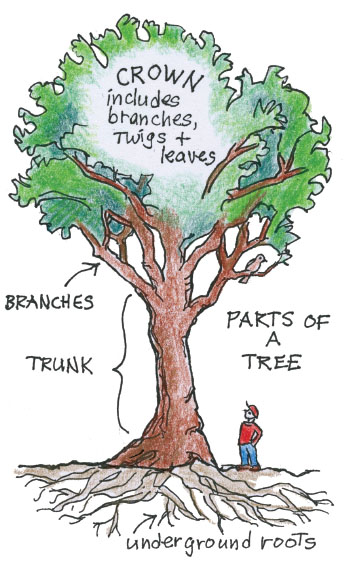

On the ground at the base of a tree, you can often see the top surface of large roots spreading away from the trunk. If you could dig up a large tree, you would find that the big roots divide into smaller roots, then into tiny rootlets, and finally into tinier roots called root hairs. You can sometimes see the entire root system of a tree when it has been blown down by a severe storm and the roots have been ripped out from the ground.

The trunk of most trees rises upward to spread out into large branches, then smaller branches, and then smaller and shorter twigs. The twigs support buds and leaves.

American elms are found in most of the eastern and central United States and in parts of southern Canada. This huge specimen is almost 100 feet tall!

The crown of this sugar maple is a beautiful sight in the fall, when the leaves turn bright orange.

The leafy top of a mature, fully grown tree is called the crown. The tops of many trees, including maples, birches, oaks, and ash trees, are rounded. An American elm has branches and a crown that grow in a fan or fountain shape. A blue spruce, often planted near homes and buildings, has a triangular shape with a pointy top. Balsam fir trees have a triangular shape too (also called a pyramid shape).

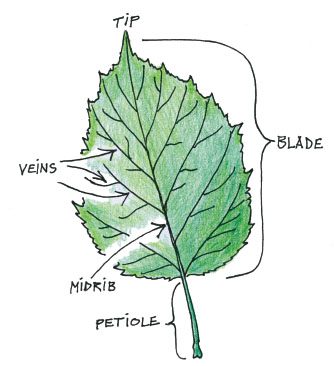

The flat part of a leaf is called the blade. Some leaves have a very wide blade, like those of the American sycamore, which can be eight inches across. Other leaves are quite narrow. The leaf of a black willow tree is only about one-half inch wide. Pine leaves are called needles because they are long and very thin.

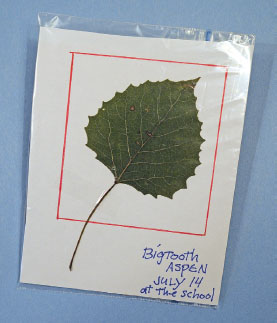

Leaves are attached to twigs by a stem called a petiole (PET-ee-ole). The petiole on the leaves of elms, chestnuts, birches, and oaks is fairly short. But the petiole on the leaf of a bigtooth aspen or on most maples is long. Look at the petiole on the leaf of any tree or shrub, and observe how long it is. Is the petiole shorter than the length of the leaf blade, or is it longer than the leaf? Bigtooth aspen, cottonwoods, and trembling aspen all have long, flat petioles, which cause the leaves to wiggle in a breeze.

The parts of a leaf. This is the leaf from a white birch, also called a paper birch. White birch is the state tree of New Hampshire and the official tree of the province of Saskatchewan, Canada.

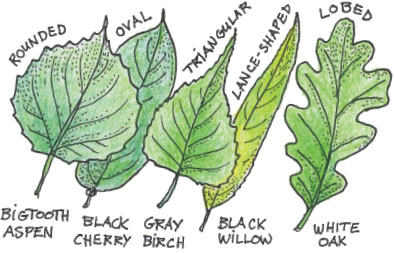

Leaves have many different shapes. Each species (type) of tree has its own leaf shape. There are many different species of maples and birch trees, and the leaves of each species have a distinct shape and size.

Some different shapes of leaves.

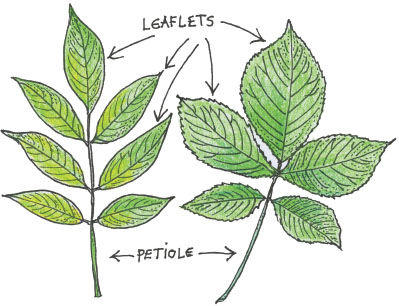

Compound leaves. Each is a single leaf, divided into several leaflets. Each leaflet is attached to the main petiole by a tiny stem. The leaf on the left is from a white ash. The leaf on the right is from a shagbark hickory. Walnut trees and locust trees also have compound leaves.

Leaves can be long and narrow, like those of willows. They can be oval, like those of cherry and plum trees. Some trees have leaves that come to a long point. The leaves of a white oak have rounded, fingerlike lobes. The leaves of sassafras trees can have three different shapes: a single oval, an oval with a “thumb” (a shape like a mitten), and a three-part leaf. All three shapes can be found on one sassafras tree!

The edge of a leaf also can be important in identification. Some leaves have a mostly smooth edge, like those of a southern magnolia. Others, like red maples and American chestnuts, have a toothed or serrated edge.

You may also notice that on some trees (and other plants) the leaves grow from the twigs opposite from each other. On other trees, the leaves are alternating (or staggered) along the branch. Once you start to look at the shape, design, and placement of different leaves, you will develop an eye for noticing details. This will help you to identify common trees, and to keep a lookout for anything different or unusual.

A few different types of magnifying glasses. The folding one can easily be kept in a pocket and carried on a nature walk. The small twig is from a black spruce.

A close-up view of the underside of eastern hemlock needles, showing silvery bands. You can easily see them with a magnifying glass.

A close-up view of the fuzz on the underside of a black cherry leaf, along the central vein.

LOOK FOR

LOOK FOR

You need good light indoors for this activity, or a bright day outside.

MATERIALS

A few different leaves, picked from trees or shrubs

A few different leaves, picked from trees or shrubs

Magnifying glass

Magnifying glass

1. Pick a few leaves from different trees or shrubs. (It doesn’t matter if you can’t identify them.)

2. Compare the upper side of the leaf with the underside. The underside is probably lighter in color.

3. Now look at the underside more closely with a magnifying glass. You will find that the veins are easier to see.

4. Look for a different texture than on the upper side. The underside may be smoother, or it may be rough, fuzzy, or hairy.

On the underside of hemlock leaves (which are short, flat “needles”), you can see white or silvery lines on each side of the central vein. These white lines are made up of special cells that surround tiny pores. You can also find white lines on the underside of balsam fir (“Christmas tree”) needles.

The underside of a black oak leaf has tiny fuzzy hairs where a vein meets the central vein. It’s a good way to tell a black oak from a red or scarlet oak. And the leaves of black cherry trees have rust-colored fuzz at the base of the leaf, just past the petiole.

Poison sumac is a shrub or small tree. Never touch a leaf of this plant! This is a very toxic plant, and even a slight touch will cause a skin rash that may need medical attention.

The compound leaf of a poison sumac shrub. Note the reddish central vein and other veins on each leaflet. This photo was taken in October, when the leaves turn yellow and can look quite pretty—but don’t touch it!

When you see an interesting tree, you might want to pick a leaf and preserve it. A fresh leaf can be preserved by pressing and drying it (which can take several days). Or you can quickly make a colorful crayon rubbing of a leaf—to decorate notepaper! This will make a copy of the leaf, so you will always be able to look at its shape and design.

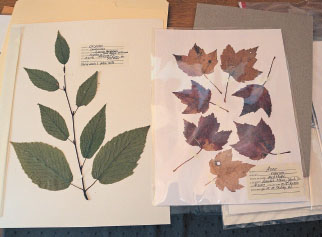

Pressed specimens from a botany collection. Some specimens in museums, universities, and science centers are more than 100 years old!

You need oxygen to breathe. So do all other animals. Oxygen is a part of the air all around you, and a lot of it comes from plants—including trees! Plants need some oxygen too, but they depend on carbon dioxide (which animals exhale). So, while you breathe in oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, plants use carbon dioxide and produce lots of oxygen!

Once you have collected several leaves that you like, you can easily press and dry them so they are preserved. Pressed leaves are often kept in scientific collections in museums and universities. Many are important historic specimens. They are lasting evidence that certain species were found growing in a particular place. Many specimens in scientific collections were pressed in the 1800s.

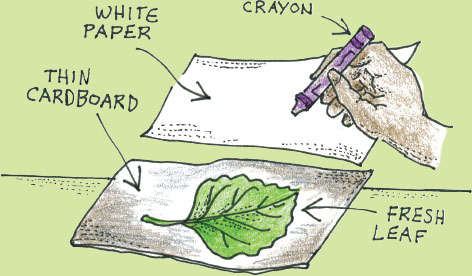

Try making crayon rubbings of different leaves in different colors. You can use your leaf rubbings as notepaper or to send a colorful message to a friend.

MATERIALS

A fresh leaf (any kind)

A fresh leaf (any kind)

Piece of thin cardboard (cardboard cut from a cereal box works best)

Piece of thin cardboard (cardboard cut from a cereal box works best)

White or light-colored paper

White or light-colored paper

Bright-colored crayons (like red, blue, or purple)

Bright-colored crayons (like red, blue, or purple)

1. Place your leaf underside up on top of the cardboard. The underside usually has the strongest veins, which will show up best in a rubbing.

2. Put the white paper over it, and hold down the paper with one hand.

3. Rub the crayon over the petiole first, because it’s easy to feel. Then rub all around the edge of the leaf. You’ll feel (and see) the edge of the leaf as you color.

4. Go over the entire leaf with the crayon, pressing hard enough so that the shape of the leaf and the veins show up.

5. You might have to try a few different leaves—or crayon colors—before you are satisfied.

6. Use your rubbing as notepaper, a card, artwork, or letter paper.

A crayon rubbing of a red maple leaf. Next to it is the leaf of a gray birch—notice the triangular shape and long pointed tip.

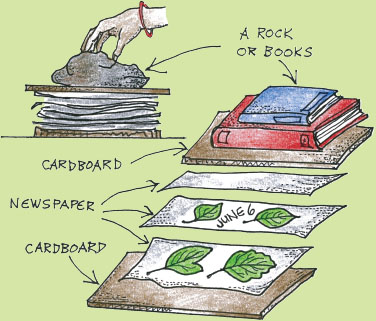

If you have found some leaves that have a shape you like, it’s easy to press them and dry them so you can keep them preserved.

MATERIALS

Several sheets of newspaper

Several sheets of newspaper

Scissors

Scissors

2 or 3 pieces stiff cardboard

2 or 3 pieces stiff cardboard

A few freshly picked leaves from trees (or shrubs)

A few freshly picked leaves from trees (or shrubs)

Something heavy, such as a few heavy books or a flat rock

Something heavy, such as a few heavy books or a flat rock

1. Cut the newspaper pages into several smaller-size squares—about the size of a sheet of printer paper.

2. Place one piece of cardboard on a flat space, like your desk.

3. Lay two or three pieces of newspaper on the cardboard, and place a few of your leaves on it.

4. Cover the leaves with more newspaper. You might need several layers of newspaper to cover more leaves.

5. Put a final piece of newspaper over your last specimens, and add a piece of cardboard to the top. Put something heavy on top of it all—a few books or a rock.

6. Let the leaves dry and press for four or five days, and then turn them over. Let them dry and press again for a few more days.

The total number of leaves on one tree is different from one species of tree to another, and from tree to tree. But a healthy, large, mature maple or oak tree can have about 200,000 leaves! In contrast to that, a small black cherry sapling, standing about four feet tall, has 172 leaves on it.

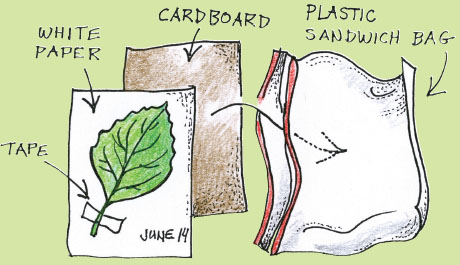

You can use one of your pressed leaves to make a specimen card that will last for many years.

MATERIALS

Cardboard

Cardboard

Scissors

Scissors

Plastic sandwich bag

Plastic sandwich bag

White paper

White paper

Pressed dried leaf

Pressed dried leaf

Tape

Tape

Marker

Marker

Colored pencils, pens, or crayons

Colored pencils, pens, or crayons

1. Cut the cardboard to fit inside the sandwich bag. Cut it small enough so that the sealing-strip at the end of the bag can be folded over and taped.

2. Cut the white paper to the same size as the cardboard.

3. Carefully place your leaf in the center of the white paper. Stick a small piece of tape across the petiole to hold it in place.

4. Use a marker, pencil, or crayon to write your name, the date, and the place you found the leaf on the paper. Be careful to not touch the leaf—it might crack or crumble!

5. Carefully slide the white paper and leaf into the bag.

6. Slide the cardboard in the bag, under the leaf and white paper.

7. Gently smooth air out of the bag and press the seal at the end closed. Fold the sealed end around to the back and tape it.

Try making cards using different leaves. You can also draw a colorful border or margin on the white paper, around the leaf, or write a note on it, to give to a friend.

Making a specimen card.

A specimen card made with a pressed leaf from a bigtooth aspen.