Some people may think that a dead tree or a rotting log is ugly and useless. But dead trees, fallen logs, and rotting stumps are very important to the healthy ecology of woodlands and forests. Dead and decaying trees provide food, shelter, and nesting sites for a variety of wildlife. They even offer a place for wildlife to communicate! And small plants such as mosses and wintergreen thrive on decaying stumps.

This standing dead tree has holes made by woodpeckers looking for insects.

A pileated woodpecker looks for insects—especially ants—in a dead paper birch. The bird is about the size of a crow.

Notice the head of a downy woodpecker, looking out from its nest hole toward the bottom of the photo. Downies are small, only about six to seven inches long.

An upright, standing dead tree is frequently a home for birds. Different species of woodpeckers, flycatchers, chickadees, titmice, and nuthatches all make their nests in the holes and hollows of dead trees. Screech owls and tree swallows nest in the hollows of trees.

The first birds to use a decaying or dead tree are often large woodpeckers, which can easily use their beaks to peck and hack their way into soft, rotting wood. They may have already pecked into the bark and wood to eat beetles, grubs, or carpenter ants. Woodpeckers can spend days excavating a hole to make it bigger or deeper, to use as a nest. They may even have to work on a few different standing trees before they find one that is just right. If the hole can’t be made big enough, or is abandoned for a better site, a chickadee or nuthatch may use it instead. The smaller birds can continue to excavate the hole further, taking out beakful after beakful of wood chips.

Small mammals also use dead trees for their dens. Flying squirrels are found across most of Canada, the eastern half of the United States, and parts of the western states. They make dens in old woodpecker nests. During the coldest winter days, several squirrels may huddle together in one den to keep warm.

A standing, upright dead tree gets shorter and shorter as it decays. It loses branches and the very top of its crown. Wind, storms, ice, and heavy snow all break off parts of the tree. What is left is often just a snag—an upright section of a hollow, rotting trunk. Snags that have been standing for several years usually have lost all or most of their bark and have a very light brown color. Even short snags are attractive to chickadees and nuthatches, which often nest only 5 to 10 feet from the ground. Chipmunks and mice usually nest in burrows, but they also use snags as hiding places or lookouts.

Screech owls nest in the hollow parts of a decaying tree, or in tree holes that have been hollowed out by other birds. (They can’t peck or hack away the wood themselves.) Screech owls live in the southern New England states southward to Florida and Texas. The one shown here is reddish, but there is also a gray color phase.

This snag has several holes in it, made by woodpeckers.

An eastern chipmunk sits atop the hollow stump of a balsam fir, which it uses as a hideout.

A decaying mossy log attracts insects, toads, and woodpeckers.

This redback salamander is just over three inches long. It crawls under rotten logs and stumps to make a nest.

An American toad hunts for insects, worms, and spiders during the night, but hides under decaying logs or stumps during the day.

Bats are other mammals that use holes in standing trees. Many species of bats use caves to nest and roost in, but some use a hollow tree or a big crack in a dead tree to roost in during the day.

After a tree has fallen over, it is still important to wildlife—big and small. As it lies on the ground, it is likely to be visited by two species of woodpeckers: the pileated and the hairy. Although both species look for insects higher up in the trees, they frequently peck apart bark and wood right on the ground.

A variety of insects, spiders, millipedes, sow bugs, and even slugs will use the log as a home, or to find food. Ants and termites will munch tunnels into the bark and wood. All of these tiny animals are food for birds and for small mammals like mice, voles, shrews, and moles.

A log that is decaying on the ground gets soft and often stays wet after a rain. Some naturalists call this condition red rot because the log is dark red-brown and stays damp. Mosses and lichens start to grow over it. Small animals are able to dig in the soil under the edge of the log and find a safe place to hide or nest. Toads can burrow under the edge of the log, and salamanders can also crawl under the rotting bark or under the log.

Many species of beetles are attracted to dead trees, snags, and fallen logs. Some wood-boring beetles are small. But one family, called long-horned beetles, are more than an inch long, with antennae that are as long as—or longer than—their bodies! Adults lay their eggs under the bark or in the wood, which they have chewed into. The beetle larvae (grubs) grow and develop in the wood, munching long tunnels as they crawl around. If you listen carefully as you stand next to a log, you might even hear the big grubs of long-horned beetles munching away. In recent years, there has been much concern over the Asian long-horned beetle (a species native to China and Korea), which is very destructive to trees in North America. As they mature, the grubs of many species of beetles munch their way out of the wood, leaving tiny piles of “sawdust” and holes where they have emerged.

A dead tree or log can be a kind of forest communication center. Hairy woodpeckers, common throughout most of the United States and Canada, use dead trees to announce their territory or attract mates. They tap their beaks rapidly on the side of a dead tree or on a large hollow branch. They tap for a few seconds at a time and repeat the tapping again and again. They peck so rapidly that you can’t count the individual taps. This rapid tapping is called drumming. Both males and females drum. The drumming is usually heard toward the end of winter and through the spring. Other woodpeckers that drum include the downy woodpecker, yellow-bellied sapsucker, red-bellied woodpecker, and the larger crow-sized pileated. The pileated woodpecker makes a slower, deeper series of taps than the others.

A woodland or forest may look like a beautiful landscape of tall, mature trees, but it’s not quite picture-perfect. A closer inspection usually reveals that some trees have dead branches or that a few are dead standing trees. You may notice that there are many decaying logs, branches, or twigs lying on the ground. Some northern coniferous forests have so many fallen branches and twigs on the woods floor that it’s almost impossible to walk around, unless there’s a trail.

It is normal for a woodland to have a variety of dead and decaying trees, snags, logs, and branches. All that rotting wood provides food, homes, and shelter for a variety of birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. The decaying trees and branches are an important part of a healthy forest ecology—a successful community of animals and plants living together.

This wood-boring, or long-horned, beetle is a bit more than one inch long, with antennae about the same length.

Large colonies of ants are frequently found in dead trees, rotten logs, and old stumps. The winged ants are males, swarming along with workers.

Even the trees in a city park may not be picture-perfect. Use your observation skills to decide whether insects, birds, or mammals have been working in the trees.

MATERIALS

Your sharp eyes

Your sharp eyes

A few trees to look at—living or dead—in a park or along a street. Or you can use a log lying on the ground.

A few trees to look at—living or dead—in a park or along a street. Or you can use a log lying on the ground.

1. Look for chips of wood, splinters of wood, or flakes of bark on the ground at the base of a tree. These are most likely the work of a woodpecker looking for beetles, grubs, or ants.

2. Is there “sawdust” under the edge of a log? That could mean that beetles or grubs have been munching into the bark or wood. Small round holes (a quarter-inch across, or less) could mean that wood-boring beetles have emerged.

3. Compare hole shapes and sizes. A rounded hole just over an inch across might be the entrance to the nest of a chickadee or nuthatch. A large rectangular hole (doorway-shaped) is the work of a pileated woodpecker pecking into the wood for carpenter ants. A hole chewed all around the edge might be the entrance to a red squirrel nest or flying squirrel nest. The squirrels chew around the entrance to make it bigger.

As you look at more evidence, you will gain the experience to judge whether birds, insects, or mammals have been at work.

Look for holes in a dead tree and try to decide whether birds or insects made them.

Fallen logs are used by male ruffed grouse for a different kind of drumming. In spring and summer, the male grouse jumps up on a log and starts to beat his wings sharply downward. He begins slowly and then whisks his wings downward faster and faster, while standing in place. As his wings are sharply whisked up and down on the log, they make a deep whump, whump, whump sound. The whumps get faster and faster until his wings are a blur—and then he stops. The grouse is announcing his territory (or advertising for a mate), just like the woodpeckers.

When a tree has been cut down for firewood or for lumber, a flat-topped stump is usually left. A more ragged, splintered stump is left when a tree falls over in a storm. It can take years for a stump to rot and decay to the ground. Beetle grubs, ants, and woodpeckers are all active munching or chipping away at it. Mammals are also at work. Skunks may scratch and dig at the stump, looking for grubs or other insects. Mice burrow under the edge of the stump, among the roots, to make their nests.

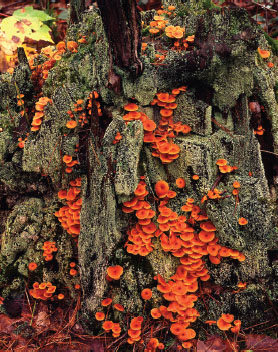

Rain, snow, and ice make the wood soft and damp and help to speed up the decay. It becomes easier for insects to lay their eggs in the soft wood and for the larvae to develop. Mold, mushrooms, and fungus also grow on stumps. Some are quite colorful and interesting. A common fungus is called turkey tail because the cluster fans out like the open tail of a turkey.

If you could watch an individual stump month after month, you might see a wood frog, toad, or small ring-necked snake wriggle among the roots around the stump. Salamanders may crawl across the stump, looking for small insects. As the months go by, moss, mold, fungus, and mushrooms might start to appear. Woodland wildflowers such as wintergreen or partridgeberry might start to grow at the sides or edge of an old stump.

Just like a standing dead tree, or a broken snag, a stump isn’t simply a dead thing—it’s alive with the activity of animals, and even other plants!

A female hairy woodpecker rests on a red maple.

A cluster of turkey tail fungus grows on a decaying stump.

It takes several years for moss to cover a stump. This mossy stump has colorful mushrooms growing on it.

If a tree has been freshly cut for firewood or to clear away a building lot or road, it will have a flat surface that may show its growth rings (also called annual rings). The rings might not be very clear, but sometimes you can see most of them. A piece of cut wood that has been sanded very smooth shows the rings best. Each ring is made by the inner layer of wood that was formed during each growing season. Some years have better growing seasons than others. A summer of drought may prevent the tree from growing very much. You may see thick or thin growth rings depending on the amount of rain that fell each year. You can count about how old the tree was by counting each ring. Each ring usually equals a year of growth.

Crows frequently use dead pines as watchtowers to keep an eye on their territory or look for food.

Many different animals live under logs or pieces of logs lying on the ground. Sow bugs, millipedes, beetles, spiders, toads, snakes, and salamanders all live under (or can crawl under) decaying logs or stumps. You might be tempted to turn over or lift rotting logs. While it might look easy to move them or kick them apart, please don’t try it. In some parts of North America, there could be a poisonous snake lying under the log! Also, it would be a tragedy to lift up a piece of old log and expose a nesting salamander—and hurt her or crush her eggs when you set the log back down. It’s best to simply observe without disrupting the homes of small woodland animals. And it’s safer.

A redback salamander guards her eggs under a piece of decaying stump. Some species of salamanders lay their eggs in ponds and streams, but others lay their eggs on land.

Find out how old a tree was when it was cut down by counting its rings.

MATERIALS

The photo below

The photo below

1. Start from the center. Count the growth rings to find out how many years old this tree was when it was cut down. Each ring equals one year (one growing season). You might not be able to count every single ring, but you should be able to count most of them.

2. Now that you’ve counted most of the rings, you can estimate about how many years old this pine tree was when it was cut to build a log cabin.

A different tree with the same circumference (or diameter) may have fewer rings—or more—depending on how good the growing seasons were from year to year.

The annual rings are easy to see on the end of this old pine log. The log is at the corner of a log cabin and has a diameter of about nine inches.

A cut piece of red oak that has been sanded smooth. The darker wood in the center is called the heartwood. The pale wood outside the heartwood is called sapwood. Some species of trees do not show a color difference between the heartwood and sapwood.

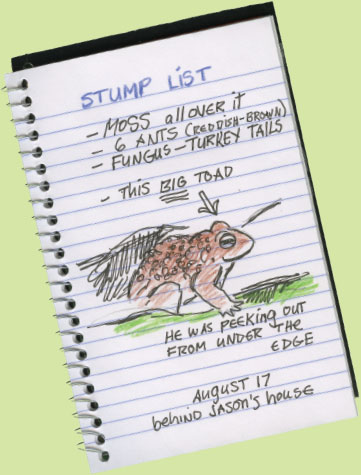

List and report—or draw—in your logbook what you have seen on a dead tree, snag, or stump.

MATERIALS

Your forest logbook

Your forest logbook

Colored pencils, pens, or crayons

Colored pencils, pens, or crayons

1. Make a list of what you have seen on a dead tree, snag, or stump. Have you seen woodpeckers use the tree? Or a crow use it as a lookout?

2. Try to divide your notes into three lists: a list for trees, a list for snags, and a list for stumps.

3. Make a drawing of something special you have seen—for example, a salamander, a colorful fungus, a big beetle, ants, or a woodpecker. Don’t worry if you can’t draw well. Your drawing is an important addition to your list. It will help you remember exactly what you observed.

Remember to write down the date and place where you saw something interesting. You might not be able to revisit some of the trees you have seen, so keeping a written list or drawing (with dates and places) can be important.

Most woodland trees have a life span of 60 to 80 years. That’s because they may be severely damaged or killed by storms. Hurricanes, flooding, tornadoes, mudslides, and ice storms can kill trees. The trees may be completely uprooted, broken, or lose so many big branches that they cannot recover. Wildfires can destroy hundreds and even thousands of acres of forests. Long periods of drought (no rain, or very little rain) can also kill trees. An infestation of some types of insects can damage or kill a tree. The emerald ash borer, a green beetle about one-half inch long, has been very destructive to trees in southeastern Canada and the eastern United States.

Lightning is an impressive killer of trees. It can strike a tree in the middle of a dense woodland or a tree standing alone in the open. It can strike a deciduous tree or a conifer. Sometimes a tree remains standing for years after it has been struck, losing its bark and slowly decaying. A direct strike often sends huge splinters flying off the trunk. The splinters are several feet long, like big spears or javelins. Sometimes the tree falls over right after the lightning strike, cracking away from the base and leaving a jagged stump. Lightning can also start forest fires that spread over many acres. Dead trees are like time machines, telling a story of the past: of storms, lightning, drought, or insect infestations. A forest tree that has lived for 60 to 80 years has lived through many different events!

This eastern white pine was struck by lightning during a late summer thunderstorm. The trunk has fallen aside, leaving a jagged stump.

Many trees in cities, in parks, and on farms can live much longer than some forest trees can. That’s because they were planted to provide shade or to create a beautiful green space. The trees are taken care of by city workers, arborists (tree care specialists), or park rangers. They are watered if there is a drought, trimmed or pruned if necessary, fertilized, and sprayed against insects. Some towns and communities even have a tree commissioner who makes sure that “street trees” get the care they need.

Some trees have become famous for their age. The Wye Oak in Wye Mills, Maryland—a white oak about 460 years old—fell over in a thunderstorm in 2002. Hemlock and red spruce stands in Maine have been estimated to be about 300 years old. The mature redwoods of California are about 400 to 500 years old, and at least one is estimated to be more than 2,000 years old. Some western junipers are about 2,000 to 3,000 years old, and General Sherman is a giant sequoia that has lived more than 3,000 years. In Chile (South America) some araucaria trees are about 1,000 years old. The oldest trees in North America are bristlecone pines in California and the western states. Some specimens are more than 4,000 years old! Recently, researchers in Sweden believe they have found the oldest tree in the world—a spruce on a mountain in central Sweden that has been alive for about 9,500 years.