Trees provide homes for a large variety of woodland wildlife. They also offer safe roosting and resting places. And the seeds, nuts, and berries from trees supply food for many animals. Many different species of birds feed on tree seeds and berries. Squirrels, deer, mice, and other mammals eat nuts, acorns, and seeds. Street trees in towns and cities offer seeds too. Maple, ash, oak, hawthorn, pine, and spruce trees are just a few of the types of trees that are important to wildlife. A healthy woodland ecology (the successful “community” of animals and plants living together in their environment) includes the food that is available from trees.

Trees also are a source of food for people. Apples, plums, pears, almonds, walnuts, and pecans are all grown in orchards or on plantations—and are just a sample of the food we get from trees for ourselves.

Many people like bananas, but we may not think about where they come from. Banana trees are native (growing wild) in Asia, but they are planted and grown in California and Louisiana. The bananas you buy in a store are usually grown in Guatemala, in Central America, or Ecuador, in South America. When you buy bananas in a grocery store, look closely at the small sticker or label on a bunch—it will show you where they were grown.

Banana trees are not large; they grow only about 20 feet tall. Although you can see lots of tiny seeds when you bite into a banana, the trees are never grown from these seeds. Instead, shoots (like small, thin trunks) grow from the base of a “mother tree,” then are pulled away and planted separately. The place where the trees are raised is called a plantation.

Walnut, hickory, and pecan trees all belong to the walnut family. Most species in the walnut family grow in the eastern and central United States. All of them produce edible nuts inside a hard shell and covered by a tough husk, or hull. If you have ever tried to crack open a walnut or pecan, you know you need a nutcracker to open the shell and get at the nut inside. (You can buy shelled pecans or walnuts in a store, which have already had the outer husks and shells removed.) Squirrels, chipmunks, and mice can chew through the husk and shell to eat the nutmeat inside.

The green outer husks of shagbark hickory nuts are thick, covering the hard shell and nuts inside. The husks (hulls) will slowly dry and become much thinner.

The nuts on the branches of a black walnut tree are covered by a greenish husk. Walnut trees usually grow 60 to 80 feet tall.

The seeds of beech trees are often called beechnuts or beech mast. Beechnuts are three-sided seeds covered by a husk that has little curved spines all over it. The seeds are eaten by blue jays, grouse, porcupines, red squirrels, gray squirrels, and chipmunks. Cultivated beech trees are sometimes planted for shade. The beech family also includes the American chestnut tree, another species that produces edible nuts for wildlife.

The seeds of a European beech (in the foreground) are three-sided. The husks have opened, and it is easy to see their rough outer texture. The European beech is often planted in the United States as a shade tree. The seeds are quite similar to those of the native American beech.

The acorns of a white oak are rounded, with a point at one end.

At least 40 different species of oaks are found across North America. Some, like the white oak, have leaves with rounded lobes. Other species have leaves that are oval shaped or have wavy edges.

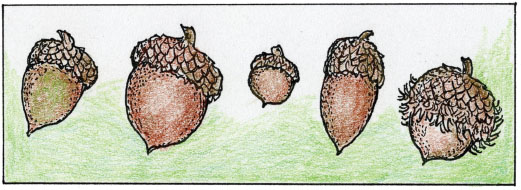

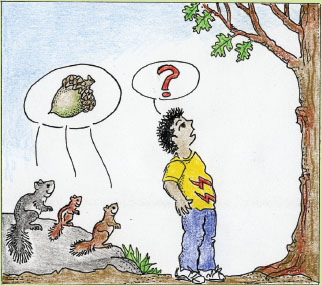

All oaks produce acorns. Acorns can be rounded or oval, are pointed at one end, and have a cap at the other end where they are attached to a twig. The caps can be flat or cup-shaped. Acorns are greenish at first but turn brown as they dry. If you could crush an acorn’s outer shell or peel it open, you would find the edible part inside. Ruffed grouse, wood ducks, and blue jays all eat acorns. Blue jays are often noted for “planting a forest,” because they store acorns for later use by poking them into soft ground—and then they forget (or don’t use) some of them. The acorns sprout and grow new oak trees! In California and the extreme Southwest, acorn woodpeckers are famous for storing acorns. They make holes in a tree trunk and then poke the acorns into the holes to store them for winter. Wild turkeys can swallow small acorns whole! Deer, squirrels, and chipmunks also eat acorns.

The acorns of black oaks and red oaks don’t ripen until the second year. So some years seem to be better “acorn years” than others, and in the good years squirrels run around frantically collecting them.

From left to right: the acorn of a white oak, red oak, pin oak (the smallest), live oak, and bur oak, which has an interesting fringed cap.

Blue jays eat oak acorns and even hide them for later use, poking them under the leaf litter or in soft ground. They also eat beech nuts and the fruit of chokecherry and serviceberry trees.

The word that botanists and naturalists use for seeds, nuts, and berries that come from trees is—fruit! We typically think of fruit as apples, pears, oranges, and such. And we usually use the word nut for such things as hard-shelled pecans and walnuts. But to a scientist, they are all the fruit of the trees.

It can be confusing. The fruit of a pecan, walnut, or hickory tree has an outer husk and then an inner hard shell, with the edible fruit—or what we commonly call a nut—inside. The edible part is sometimes called the kernel, or nutmeat.

But there are even more types of tree fruit. The fruits of maples and ashes are called samaras (sa-MAR-ahs). The samaras have a seed at one end and a flat papery “wing” attached. The berries of mulberry trees and cherry trees are fruit also. The fruits of birch trees are called catkins. Catkins are dangling clusters, about one to two inches long. Male catkin flowers contain pollen—tiny grains produced by the male parts of plants. Female catkin clusters develop seeds. The fruits of many species in the willow family are seeds with a fluffy, cottony “parachute” attached. Aspens and cottonwoods are famous for the fluffy, silky hairs that spread out and allow each seed to float on a breeze and drift away from the tree.

The fruits of ash trees are long and narrow, and grouped in pairs or clusters. Each seed has a thin papery blade or “wing” at one end. The entire fruit is called a samara (sa-MAR-ah). Several species of ash trees are found in North America, and the seeds from the samaras are eaten by bobwhite quail, pine grosbeaks, and purple finches.

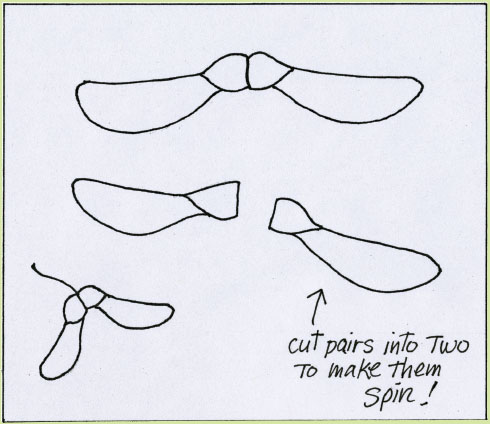

Maple trees also have fruits that are called samaras. A flat wing is attached to each paired seed. Red maple trees have samaras that are reddish at first and then dry to greenish-brown. Maple samaras are eaten by evening grosbeaks, which use their strong, thick beaks to munch away the “wing” and then open the covering of the seed. The samaras of sugar maples and Norway maples are mostly green when fresh. As the samaras dry, the pair of seeds often split apart. Maple samaras are often called helicopters because they spin around and around as they fall to the ground.

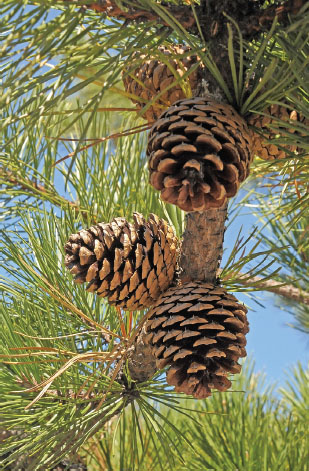

Pines, spruces, redwoods, sequoias, and several other types of trees bear woody cones made up of curving scales. At the base of each scale are small rounded seeds with a flat papery “wing.” The seeds of conifers are small. Most conifers are called evergreens, because they don’t lose all their leaves each autumn. (The leaves of larch trees, however, turn golden brown and completely fall off.) Seeds from the cones of conifers are eaten by pine siskins, nuthatches, chickadees, and crossbills. These birds can pry out the seeds from the cones that are hanging on the trees.

Red squirrels and chipmunks look for pinecones that have fallen to the ground. They sit and take apart the cones, leaving a telltale pile of cone scales. You may see a pile of cone scales on a stump or rock, where a chipmunk or squirrel has sat and worked at finding the seeds. The cones of longleaf pine, eastern white pine, and pitch pine need two years to mature.

The gray squirrel is a common sight in forests and even city parks, where it scampers around looking for acorns, hickory nuts, and beechnuts.

Samaras from a red maple develop and fall from the branches early. This picture was taken in May.

Clusters of samaras from a white ash tree that have fallen to the ground in late September. The seeds are the narrow oval bulges closest to the twig.

If you do this activity outdoors in a breeze, the seeds can really move!

MATERIALS

Maple samaras that have fallen to the ground (Red maple samaras fall as early as May and June.)

Maple samaras that have fallen to the ground (Red maple samaras fall as early as May and June.)

Paper

Paper

Drawing below right to trace

Drawing below right to trace

Pencil

Pencil

Scissors

Scissors

1. If the maple samaras you find on the ground are still paired, break them in half. (That way, they will spin better.)

2. Hold at least three or four maple samaras (the broken “singles”) in your hand, high above your head.

3. Let the seeds go, and watch as they spin and whirl down!

Or: If you can’t find any maple samaras (or it’s the middle of winter), make your own following these steps.

1. Use the outline model below to trace or copy some samaras, and cut them out. The big samaras are from Norway maples. (Their actual size is nearly four inches across!)

2. Cut the joined pair in half, so you have two winged seeds. The much smaller samaras from a red maple are shown at the bottom, for comparison. (But they still spin!)

3. Hold the paper samaras above your head, and drop them. They will whirl and spin down just like real samaras! You can make as many samaras as you want—and drop a whole bunch of them!

Many trees that are native to North America bear fruit in the form of small berries. The fruit usually has a soft outer pulp that birds and mammals can eat. The many species of hawthorn, mulberry, chokecherry, black cherry, dogwood, and serviceberry (also called Juneberry) have rounded fruits that ripen in the autumn and are eaten by wildlife through the winter. Cedar waxwings are among the birds frequently seen eating hawthorn berries. Purple finches feed on the dark fruit of serviceberries. And cardinals eat the berries of dogwoods.

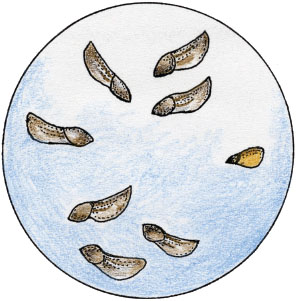

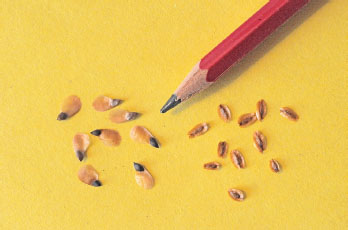

The seven winged seeds from an eastern white pinecone (on the left) are just over one-half inch long. Compare the pine seeds with the one smaller seed on the right, from a red spruce.

The cones of a pitch pine are shorter and more rounded than the cones of a white pine. Each scale of the cone is tipped with a pointy spine.

The cones of an eastern white pine are about six to eight inches long.

Seeds from a black spruce (left). They are similar to the seeds of a pine, but smaller. On the right are seeds from an arborvitae, a conifer often used for landscaping near houses and offices.

Once the trees have produced seeds, nuts, and berries, birds and other animals eat or collect the “harvest.” By the middle or end of summer, cherry trees, hawthorns, and serviceberry trees have fruit on them. Later in September and October, the large nuts on hickory and walnut trees have already formed. The small cones of arborvitae and the larger cones of pine and spruce trees have also formed. From late summer and right through the winter, all this food from trees will be sought by birds, squirrels, deer, chipmunks, and other animals.

The fall is a beautiful time of year as the leaves of most deciduous trees, especially in the northern parts of the United States, turn yellow, orange, or bright red. Red maple is named for its scarlet autumn leaves. Quaking aspen and bigtooth aspen have leaves that turn yellow-gold. The leaves of black tupelo (pepperidge tree) turn deep red-purple. The star-shaped leaves of the sweet gum tree, which grows in the southeastern states, turn deep gold at first and then dark red-purple.

As fall approaches, the green color (chlorophyll) of leaves fades and disappears, and the substances (chemical pigments) that make other colors take its place—giving us an autumn treat of bright, colorful hillsides and woodlands. Trees in Canada and the northern United States are the most colorful. Many people plan their fall vacations in the hills of Vermont and other New England states so they can see the beautiful scenery.

Palm trees, some species of live oaks, and some acacias growing in the southern states or southern California remain green. Eucalyptus trees, native to Australia but planted in California, Florida, and Hawaii, remain green also.

Seeds from the cones of the pinyon pine, a species found in the American Southwest. This handful of large seeds is from pinyons growing in New Mexico. The nuts inside each hull are eaten by a variety of small birds, small mammals—and people!

Purple finches feed on a variety of tree seeds and the fruit of serviceberry trees. This is a male.

The fruit of a wild black cherry tree. This photo was taken at the end of August, when the berries were still ripening.

Keep a lookout for food from the trees that animals could eat, and take notes. Notes and lists written “on the spot” outdoors are called field notes by biologists and naturalists. They are important records of what you have observed.

MATERIALS

Your sharp eyes

Your sharp eyes

Forest logbook and pencil

Forest logbook and pencil

Trees

Trees

1. Look at (and under) the trees in your neighborhood for seeds on the ground, nuts on the trees, or twigs with berries that animals might eat.

2. Look for birds, squirrels, or chipmunks near the trees, or on the ground under the trees, that seem to be looking for food.

3. Write down what you see in your forest logbook—even if you can’t identify the tree. Write down the date and place, and whether the seeds or fruit have fallen to the ground or look fresh or dried.

There are many different species of trees. You have already observed a wide diversity (variety) of shapes, colors, and textures of leaves and bark. In any forest or woodland, there is a diversity of tree species. A deciduous forest may seem to be mostly oaks, but maples and birches may be mixed in. The understory of a forest usually includes younger trees, but low-bush blueberry, sheep laurel, or hazelnut could be growing too. Small flowering plants on the woods floor may include several different species of wildflowers, ferns, and mosses.

A woodland also has a diversity of animals: birds, mammals, insects, spiders, reptiles, and amphibians—all with different shapes, sizes, textures, colors, and patterns. This wide range of diverse plants and animals is called biodiversity (bi-o-dih-VERS-ity). The biodiversity can be very different from habitat to habitat. The plants and animals living in a dry desert are different from those living in a swampy wetland. An ecologist studies the biodiversity of animals and plants that successfully live, feed, and raise their young in a habitat.

As you take a walk in the woods, or even near street trees, you are likely to see evidence that birds or other animals have found food. You can write your observations in your forest logbook.

MATERIALS

Your sharp eyes

Your sharp eyes

Forest logbook and pencil

Forest logbook and pencil

Area with trees

Area with trees

1. Look at the tops of stumps or rocks, or at the base of a tree, for a pinecone that a chipmunk or squirrel has taken apart. You might find a pile of scales from a cone, or a cone that has had half its scales ripped away.

2. Look for acorns on the ground. Some may have a small hole in the side from an insect. Others may have part of the shell chewed open and the nut inside eaten—probably the work of a mouse, chipmunk, or red squirrel.

3. Is there a hickory or walnut tree in the area? You may find that the nuts have fallen to the ground, with the greenish husks still on. Visit the area a few days later to see if the nuts are gone.

4. Do you see a lot of bird activity in a tree? In the fall, cedar waxwings visit hawthorns in small flocks to eat the berries. Cardinals come to dogwood trees to feed on the fruit. If you see a tree with lots of berries on it one day, revisit it a few days later to see if the fruit has been eaten.

Depending on weather conditions and soil, trees produce more seeds, nuts, and fruit during some years and less during other years. It is important to write down what you find in your forest logbook, because you may not see as much the next year. Be sure to include the dates!

This is where a chipmunk sat and took apart the cone of a white pine, scale by scale, to get at the seeds inside. All the scales are left in a pile.

Two acorns have been chewed open by a red squirrel, leaving just the shells.

Many holiday cards have a picture of holly berries, or winter holiday decorations using hollies. The red berries are produced only by the female holly. Female American holly trees and female English holly trees both need to have a male holly growing nearby. The flowers on the male trees produce tiny pollen grains, which have to reach the flowers on the female holly tree so the berry can develop.

Both American and English yew trees also bear male and female flowers on separate trees. English yews are frequently planted as landscaping shrubs or hedges and kept pruned and trimmed so they don’t grow very tall. But just like the holly trees, pollen from the flowers on male yews has to reach the flowers on the female trees growing nearby. Box elder (a species of maple), ginkgo, and common juniper (a conifer) trees also have male flowers on one tree and female flowers on another. Sometimes people wonder why their holly or yew doesn’t develop beautiful red berries. It’s because their tree is female, and no male was planted along with it!

Pollen grains are very tiny—almost like dust—and can be spread by the wind; by insects such as bees, wasps, and butterflies; or even by hummingbirds. Most trees, shrubs, and small flowering plants depend on the wind or on pollinators to produce seeds, nuts, and berries. The flowers on many species of trees have both male and female parts in each blossom. Apple trees and hawthorn trees are good examples: each flower has tiny stalks called anthers, which have pollen grains on them, and a central stalk (the female part) called a pistil. Birches and many other species of trees have separate male and female flowers growing on the same tree.