“CHRISTIAN DIOR TAUGHT ME

THE ESSENTIAL NOBILITY OF A

COUTURIER’S CRAFT.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

DIOR’S DAUPHIN

A

In fashion history, Yves Saint Laurent remains the most influential designer of the latter half of the twentieth century. Not only did he modernize women’s closets—most importantly introducing pants as essentials—but his extraordinary eye and technique allowed every shape and size to wear his clothes. “My job is to work for women,” he said. “Not only mannequins, beautiful women, or rich women. But all women.” True, he dressed the swans, as Truman Capote called the rarefied group of glamorous socialites such as Marella Agnelli and Nan Kempner, and the stars, such as Lauren Bacall and Catherine Deneuve, but he also gave tremendous happiness to his unknown clients across the world. Whatever the occasion, there was always a sense of being able to “count on Yves.” It was small wonder that British Vogue often called him “The Saint” because in his 40-year career women felt protected and almost blessed wearing his designs.

Although the Paris-based couturier wished that he had invented denim jeans—describing them as “the most spectacular, the most practical, the most relaxed, and nonchalant,” to Vogue’s Gerry Dryansky—he was behind such well-cut staples as the pea coat, the safari jacket, the trench coat, the pant suit, Le Smoking (the female tuxedo), and the introduction of black tights as the chic alternative to pale hosiery. Following in the footsteps of Coco Chanel, Saint Laurent was inspired by black, yet he was a superb colorist who with his bold choice of fabric knew how to brighten an outfit and flatter the complexion.

As a demonstration of Vogue’s attention to promising fashion talent, Saint Laurent had strong links with the magazine from the very start of his career and throughout. It was via Vogue’s Michel de Brunhoff that he met Christian Dior, his first and only boss. It was through the enthusiasm of Vogue’s Diana Vreeland that the American public became instantly sold on Rive Gauche, Saint Laurent’s ready-to-wear line. Meanwhile, Helmut Newton’s iconic Smoking portrait taken in 1975 and other memorable images by the likes of Richard Avedon, David Bailey, Guy Bourdin, and Irving Penn were first viewed within the pages of Vogue.

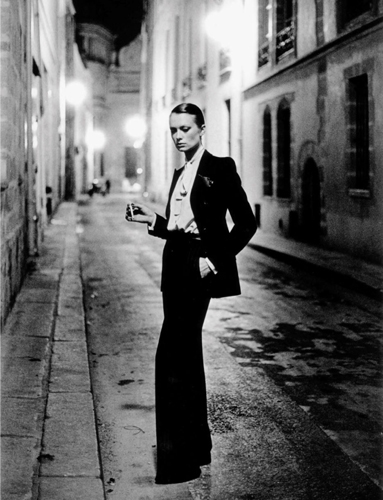

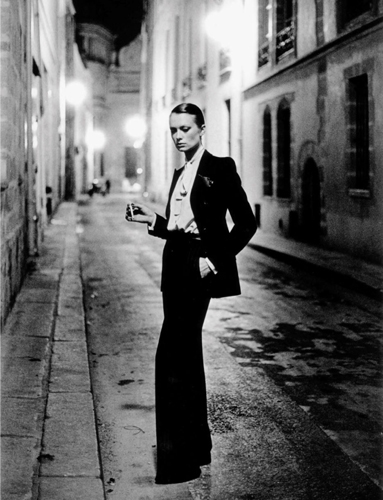

Helmut Newton said Saint Laurent inspired his “best fashion photos.” His mythic portrait of Vibeke Knudsen wearing Le Smoking on the rue Abriot appeared in Vogue Paris in 1975. The pairing of tailored pant suit and soft blouse typified Saint Laurent’s masculine-feminine ambiguity.

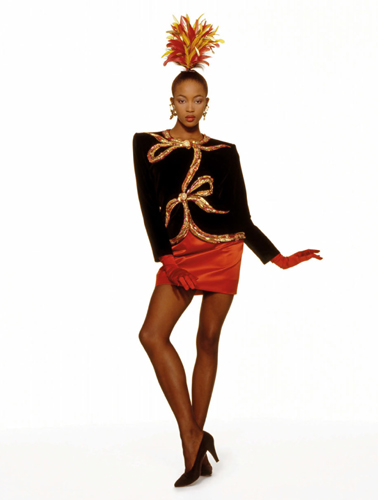

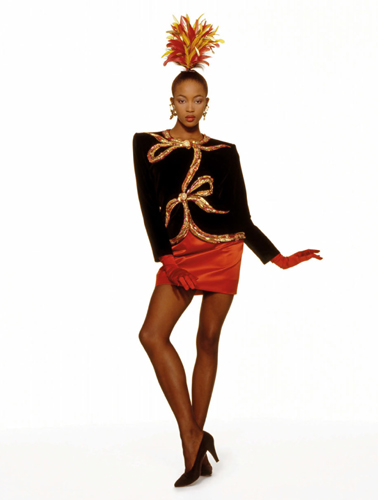

Naomi Campbell, a frequent Saint Laurent model, photographed by Patrick Demarchelier in 1987 as a haute-couture-clad showgirl—a favorite nighttime look of the couturier’s.

Rive Gauche shirt, sunglasses, and jewelry, are exotically displayed on Marie Helvin, another Saint Laurent favorite, photographed by David Bailey in 1975.

“A GOOD MODEL CAN ADVANCE FASHION BY TEN YEARS.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

Carla Bruni photographed by Dewey Nicks in 1994, wearing Saint Laurent’s short couture silk faille evening dress, highlighted with jewelry designed by Loulou de la Falaise.

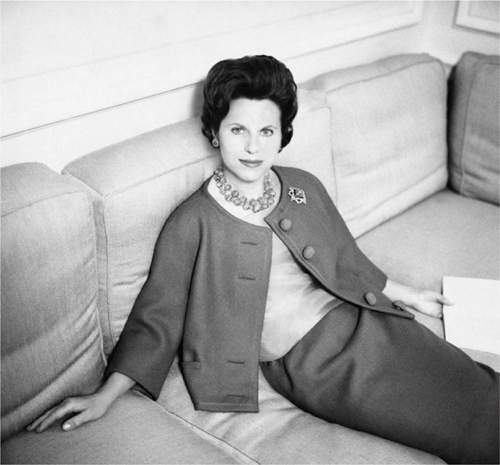

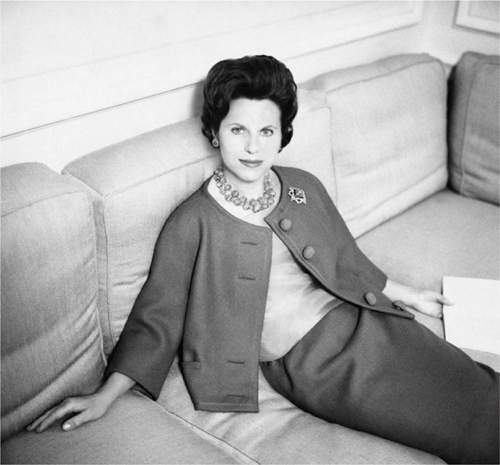

Lucienne Saint Laurent, photographed for British Vogue by Willy Rizzo in 1960 with “the irrepressibly pleased expression of someone whose son has just pulled off an immensely successful coup.” To set off her dramatic coloring, she was wearing a turquoise cardigan suit, from Saint Laurent’s couture collection for Christian Dior.

Saint Laurent epitomised the expression “highly strung.” Pierre Bergé, his business partner and one-time lover, described him as being “born with a nervous breakdown.” Still, whatever his mood—“I am a persistent depressive,” he told British Vogue’s Lesley White—or mental state, Saint Laurent never lost his adoring fashion audience. The interest in his personal welfare never faded. Though viewed as “the king of couture” and one of the “great talents,” Saint Laurent was seen as human, and he touched people by his vulnerability—no doubt because he seemed authentic, and had always dared to be different and romantic. His declaration that “for a woman to look beautiful all she needs is to be in the arms of the man she loves” demonstrated this. A poetic thought, it suggested that he cared about women beyond clothes: Yves le Séducteur—the designer who both seduced with his perfect proportions and with his person.

From an early age, adoring females surrounded the designer. Born on August 1st, 1936 in Oran, Algeria, Yves Henri Donat Mathieu-Saint-Laurent was the apple of his mother Lucienne’s eye. Cherubic, with large blue eyes and wide, smiling mouth, he displayed none of the anguish that would later cloud his features. He was a happy and cherished petit prince. Two younger sisters—Michèle and Brigitte—were to follow. “I love my daughters, of course,” Lucienne told Vogue’s Dryansky, “but for Yves, there’s always been something very strong and very special.”

‘Women are intrinsically mysterious, veiled, enigmatic.’

YVES SAINT LAURENT

Illustrating Saint Laurent’s sensual way with fur, Nancy Donahue sports Rive Gauche’s suede coat, lined in squirrel with silver fox collar. Photograph by Eric Boman, 1980

Cindy Crawford wears Rive Gauche’s one-sleeve silk top with tulip sarong, an example of Saint Laurent’s fondness for an asymmetrical style. Photograph by Patrick Demarchelier, 1987.

The Saint Laurent family led a privileged existence. “There were many lovely dinner parties at our comfortable house in town,” he wrote, “and I can still see my mother, about to leave for a ball, come to kiss me goodnight, wearing a long dress of white tulle with pear-shaped white sequins.” His father, who owned an insurance business as well as being involved in the occasional movie production, was descended from distinguished public servants who had fled Alsace, France, when the Germans took it as war booty in 1870. “One of my ancestors wrote the marriage contract between Napoleon and Josephine and was made a baron for it,” Saint Laurent revealed. His mother’s background was more complicated. Her parents—a Belgian engineer and his Spanish wife—had handed her over to an Aunt Renée, the wife of an affluent architect, living in Oran. No expense had been spared for Lucienne, referred to as la gata (the cat) owing to her sparkling green eyes, which were enhanced by her copper-colored hair. An early poster girl for her son’s designs, there was nothing remotely provincial about her appearance, but there again, Oran, then part of the French Empire, was one of the largest ports on the Mediterranean. “Our world then was Oran, not Paris,” wrote Saint Laurent. “Oran, a cosmopolis of trading people from all over … a town glittering in a patchwork of all colors under the sedate North African sun.”

“The intense melting pot of lives I knew in Oran … marked me,” he told Vogue’s Joan Juliet Buck. He recalled the warships and all the wartime uniforms. “People tried to have some glamour in their lives because they were close to death,” he continued. He had an extraordinary artistic talent, evident from the age of three, which his mother encouraged. He enchanted his two sisters, amusing Brigitte with his witty caricatures of Oran’s church-going public, and arranging “no adults allowed” couture fashion shows. Aware of his precocious talent, Saint Laurent was keen for acclaim. As he later confessed, “I had just blown out the candles for my ninth birthday cake when, with a second gulp of breath, I hurled my secret across a table surrounded by my loving relatives: ‘My name will be written in fiery letters on the Champs-Elysées.’”

His home life was imaginative and fun, but his school days, spent at the Collège du Sacré-Coeur, the Jesuit Catholic boarding school, were unmitigated hell. Extremely thin and fey-looking, an appearance emphasized by the tight jackets and ties that he chose to wear, Yves became the target for the macho boys in his class. “I wasn’t like the other boys. I didn’t conform. No doubt it was my homosexuality,” he told Le Figaro, the French newspaper, in 1991. “And so they made me into their whipping boy. They beat me up and locked me in the toilets … As they bullied me, I would say to myself over and over again, ‘One day, you’ll be famous.’”

Saint Laurent never told his family about the daily attacks. Still, the very idea of them made him violently sick, every morning. Fortunately his keenness to create clothes for his mother—her dressmaker began to use his sketches—as well as his love of the movie theater and theater would outweigh the horror of his schooldays. A touring production of Molière’s play L’Ecole des Femmes, directed by the actor Louis Jouvet with sets by Christian Bérard, led to Saint Laurent’s viewing theatrical design as a professional option. Suddenly, all the 12-year-old could talk about was theater. His parents let him use an empty room for productions that he wrote, staged, and cast using his sisters and cousins as actors.

Passion for the stage did not stop the 17-year-old Saint Laurent entering the International Wool Secretariat fashion competition. It led to his winning third prize and going with his mother to Paris in the fall of 1953. Thanks to his father’s contacts, he met Michel de Brunhoff, the celebrated editor of Vogue Paris. Noted for his relationships with designers like Elsa Schiaparelli and Christian Dior, de Brunhoff was in a position to help Saint Laurent in the fashion world. The young man’s mix of creative authority and extreme fragility tended to induce assistance. Indeed, Vogue’s de Brunhoff was the first in a long line of influential people who were supportive of Saint Laurent.

“I came to Paris determined to burst out on the world, one way or another.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

A

De Brunhoff was insistent that his young protégé finish his baccalaureate exams. Saint Laurent followed his advice, and also entered the 1954 International Wool Secretariat competition that boasted 6,000 entrants. His black cocktail dress complete with a veil worn over the face won first prize, while a certain Karl Lagerfeld won best jacket category. A photograph captures the event. Fanciful as Saint Laurent appeared—“elegance is a dress too dazzling to wear twice,” he had said when presenting his dress—he actually possessed tremendous self-worth backed up by an eerie instinct. The year before, he and his mother had been admiring the fashion finery along Paris’s avenue Montaigne when Saint Laurent had suddenly looked up at Christian Dior’s headquarters and announced, “Maman, it won’t be long until I’m working in there.”

To improve his couture technique, de Brunhoff encouraged Saint Laurent to attend Paris’s best fashion school, the Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne. However, three months on, the 18-year-old was bored by the experience, no doubt because he was both professionally focused and had already learned so much from his mother’s dressmaker. Concerned by his son’s general apathy, Charles Mathieu-Saint-Laurent recontacted de Brunhoff, and Saint Laurent returned to the Vogue Paris offices and stunned de Brunoff and Edmonde Charles-Roux, the magazine’s new Editor-in-Chief, with his latest batch of sketches. They strongly resembled Christian Dior’s new A-Line designs, a collection that was still under wraps. Frantic calls were made to Monsieur Dior who, after meeting Saint Laurent, hired him on the spot. “Working with Christian Dior was, for me, the achievement of a miracle,” Saint Laurent told Dryansky. “I had endless admiration for him.”

“I was torn between the theater and fashion. It was my meeting with Christian Dior that guided me toward fashion.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

The 18-year-old Yves Mathieu-Saint-Laurent wins first prize in the dress category of the International Wool Secretariat, December 1954. This cocktail dress, chosen from an entry of 6,000 anonymous sketches, indicates his instinct for balance. Since it closed with buttons on the right, the shoulder was left bare.

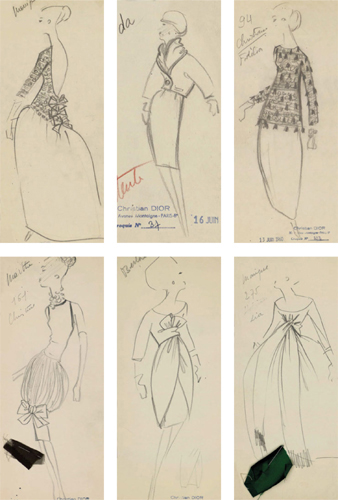

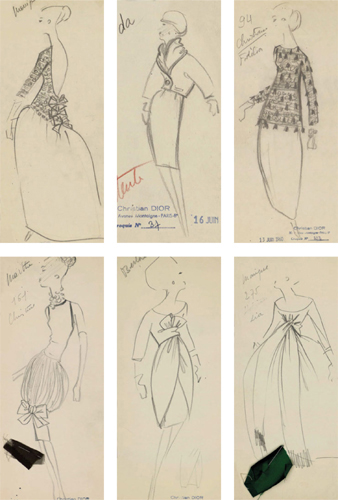

Saint Laurent’s couture drawings for the house of Christian Dior. Details like the tulip-shaped skirt and exposed back would feature in his own, future, fashion house. Throughout his career, few were not awed by the quick intelligence and fluid harmony behind his croquis (fashion sketches).

Christian Dior’s New Look collection in February 1947 had made him France’s most successful and famous couturier. His designs promoting a corseted hourglass torso as well as ankle-grazing hems—controversial owing to postwar fabric rationing—caused international fashion fever; Jean Cocteau, France’s star poet and writer, was quoted as saying, “The ‘New Look’ is being given the importance of the atomic bomb.” Within a few years, his clients consisted of A-List Hollywood sirens like Lauren Bacall, Marlene Dietrich, Ava Gardner, and Rita Hayworth as well as well-heeled members of society such as the Begum Aga Khan, Daisy Fellowes, Patricia Lopez-Willshaw, and the Duchess of Windsor.

Rigorous about quality, the Christian Dior couture house was the perfect place for Saint Laurent to land because it would teach him about the importance of discipline in fashion. Brilliant as Saint Laurent was, he needed structure to calm and temper his creative imagination. Working alongside Monsieur Dior—a designer who would have his eternal respect both for succeeding and for being the friend of artists like Cocteau and his hero Christian Bérard—Saint Laurent would learn the essential basics. “Essential basics” that would underpin his future fashion house.

Christian Dior’s seamlessly run couture house consisted of Jacques Rouët, the financial director; Suzanne Luling, who was in charge of the salon and vendeuses (the sales women); and three women who ran Dior’s inner sanctum. Referred to as the “three fates” by the photographer Cecil Beaton, they were: Madame Raymonde Zehnacker who acted as the designer’s alter ego; Madame Marguerite Carré, a technical expert who headed the ateliers; and Madame Mitzah Bricard, Dior’s unofficial muse who created hats. Although fairly hierarchical, the “worker bee” atmosphere was civilized, and that stemmed from Dior himself. Modest and even-tempered, the couturier was rare in his world for being polite, industrious, and open-minded, though he was no pushover: employees were fired for not recognizing him, chewing gum, and other uncouth behavior.

Saint Laurent was wildly fortunate to fall into the fashion net of a true visionary who created one of the premier global brands, but there were mutual benefits. Saint Laurent had excellent taste and was full of fresh ideas and the latter was vital to Dior. After the excitement of the New Look, clients and buyers were expecting a surprise from Monsieur Dior every season. It was hard to keep up the momentum and the couturier depended on the assistants in his studio. According to Saint Laurent, he and Dior had a formal relationship. “We were very shy with each other and never had deep conversations,” he told British Vogue’s White. “But he taught me many things, that frivolity is not a lack of intelligence … and the rules of fashion. It was an incredible place to work.”

Still, it has to be emphasized how painfully reticent and timid the bespectacled Saint Laurent was. Walking along the house’s corridors, his tall, thin figure would press itself into the walls. His behavior either brought out maternal instincts—“you just wanted to hug and console him,” said one Dior seamstress—or intrigued. Initially, Victoire, the Dior model, was reminded of a monk until the sultry brunette made a concerted effort to sit down and talk to Saint Laurent. “Then I was thoroughly charmed,” she admits. And so began Saint Laurent’s fabled way with women in the fashion world that continued throughout his life. Owing to his close relationship with his mother, he knew exactly how to enchant.

Nevertheless, it was a charm reserved for women. In Dior’s studio, Saint Laurent refused to greet or speak to Yorn Michaelsen, a handsome fellow assistant who sat next to him. Michaelsen recognized that Saint Laurent was a genius’ but behind the “shrinking violet” façade lurked “a monster.” “He held a huge opinion of himself,” recalls Michaelsen, as well as requiring “a court of admirers” led by the likes of Victoire. Of course, this exclusionary behavior was and remains fairly common practice in fashion but what is interesting is that Dior was aware of it and dismissed it as youthful silliness. A lesser designer might also have tried to block Saint Laurent’s talent or pretended that his sketches were his own. Instead, the thoroughly generous Dior—who forgave and accepted the foibles of the gifted—drew attention to his youthful assistant. Prior to collection time, the young protégé would deliver his sketches—mini marvels achieved back at his parent’s home in Oran—that ultimately made up a large percentage of the show and, internally chez Dior, were recognized for doing so. Had Saint Laurent nursed doubts about his future, a meeting between his mother Lucienne and Dior confirmed that he was the designer’s unofficial dauphin. The idea was that Saint Laurent would have several years to mature into the position. Unfortunately, only months later, Dior died of a heart attack, on October 24, 1957.

Marie-Hélène Arnaud, later Coco Chanel’s muse, offers soignée attitude to Saint Laurent’s “trapeze-style” tulle and silver-specked evening dress for Christian Dior, described by Vogue as “flaring out over the narrow sheath beneath.” Photograph by Henry Clarke, 1958.

A much-loved figure and viewed as the hero who saved French couture, Dior was given a statelike funeral at Eglise Saint-Honoré-d’Eylau. It was noted that Saint Laurent was seated in a prominent pew, near famous couturiers like Cristóbal Balenciaga and Pierre Balmain, paying their respects, but there was a burning question: Would Marcel Boussac, who financed the house of Dior, pull the plug on the 60 million franc business? Among Dior’s management, there were fears that Saint Laurent was simply too inexperienced to take over the reins. An official press conference was then conducted at Christian Dior’s salon on avenue Montaigne. Jacques Rouët announced a creative team of four individuals who had all worked with Dior, namely Raymonde Zehnacker, Marguerite Carré, Mitzah Bricard, and Dior’s 21-year-old assistant who still went by the name Yves Mathieu-Saint-Laurent.

Awkward as he seemed, Saint Laurent privately basked in the spotlight and enjoyed the drama of the occasion. Rushing to his parent’s home in Oran, he later described himself “in a state of complete euphoria” when designing the collection because he sensed that he was “going to become famous.” After three weeks, he returned with 1,000 sketches. There were a multitude of ideas but Zehnacker, Carré, and Bricard deftly edited them down to 178 looks.

Described as “shadowed with feathery roses,” this fichu-tied dress for Christian Dior demonstrated Saint Laurent’s eternal admiration for a bold green and patterned print. Photograph by Anthony Denney, 1958.

On January 30, 1958 Yves Saint Laurent, as he became officially known having dropped the Mathieu, delivered his first Dior collection. It was called “Trapèze” owing to the main silhouette that was like a trapezium: fitted at the breast and then flared out below the knee. Light, breezy, and lacking an iota of Christian Dior’s signature construction and padding, the presentation was hailed as a triumph.

Beckoned into Dior’s Grand Salon, Saint Laurent received a standing ovation. “The reaction of joy and relief was terrific,” reported British Vogue. “People cried, laughed, clapped and shook hands. For almost an hour no one would leave.” The new star was then led up the stairs to the second floor’s wrought iron balcony where Monsieur Dior famously used to take his bows. The image of Saint Laurent being cheered and clapped by cab drivers and passersby was caught on camera. The next morning, the newspaper sellers shouted, “Saint Laurent has saved France.” It was news that was furthered by a fleet of glowing reviews.

In Saint Laurent’s opinion, he resembled a “studious schoolboy” during his Dior days but the French media used expressions like “sickly child,” “shy and stooped,” and “a fawn in the forest.” And it is hard not to agree with Alicia Drake, the author of The Beautiful Fall: Fashion, Genius and Glorious Excess in 1970s Paris that, from the very beginning, “the image conjured up” of Saint Laurent was that of “victim in victory, of a youth sacrificed for fashion.” “This would be the highly emotive vernacular that would stay with him and describe him throughout his career,” she wrote. Indeed, whatever Saint Laurent did, tended to inspire protective feelings.

‘Suddenly the house of Dior had taken a real youth pill.’

SUSAN TRAIN, VOGUE

Yves Saint Laurent, after his Christian Dior show in July 1960 with “cabine” models, Patricia, Laurence, Fidélia, Déborah, and Valérie. The couturier reveled in their company. Like his mentor Dior, he recognized that they were essential to his designs.