“I WORK, I DRAW A LOT.

I DON’T LET MYSELF BE INFLUENCED.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

FASHION’S NEW GENIUS

A

In the October 1960 issue, Vogue published a photograph of one of Yves Saint Laurent’s final designs for the house of Dior. Taken by Irving Penn, it was a black crocodile jacket, trimmed with mink. Edgy and hip, it lacked the jeune fille sedateness of his “Trapèze” line and suggested that little Yves had grown up and rebelled. He had—by delivering the “Beat” collection, which was inspired by Juliette Gréco, the French singer and cool queen of Paris’s beatnik scene. “This was the first collection in which I tried for poetic expression in my clothes,” Saint Laurent wrote. “Social structures were breaking up. The street had a new pride, its own chic, and I found the street inspiring, as I would often again.” Although the mostly black clothes sold well, the Dior management were appalled.

Unlike Christian Dior who was always prepared to take risks, Madame Raymonde and the others running his empire were fairly conservative. No doubt it explained both the hiring and secret holding onto the French designer Marc Bohan, in spite of Saint Laurent’s initial success. Mature and predictable in style, Bohan was kept in London, just in case Dior’s young Dauphin did not cut the mustard.

Early photographs of Saint Laurent, taken with Mesdames Raymonde, Marguerite, and Mitzah, suggest a polite young man in the company of his maiden aunts. Later ones, however, indicate more confidence, no doubt because he had branched out to design costumes for Roland Petit, the enfant terrible of the ballet world, and because he had a lover, the 27-year-old Pierre Bergé. Many books, many organized by Bergé, have described their tumultuous and extremely productive relationship. And since Bergé was a pugnacious force of nature next to the more elegant, retiring Saint Laurent, it might be presumed that Bergé is sounding his own trumpet. Nevertheless, the Napoleonic Bergé deserves recognition for his part in Saint Laurent’s illustrious career because he always believed in the designer and fought for him tooth and nail, whatever the circumstances. Without Bergé, it is unlikely that Saint Laurent would have soared to such great heights. Saint Laurent was a fashion genius but he was an extremely neurotic thoroughbred who needed hand-holding in every single instance, and Bergé, who would regard him as the great love of his life, had both the intelligence and energy to cope with the couturier’s demands.

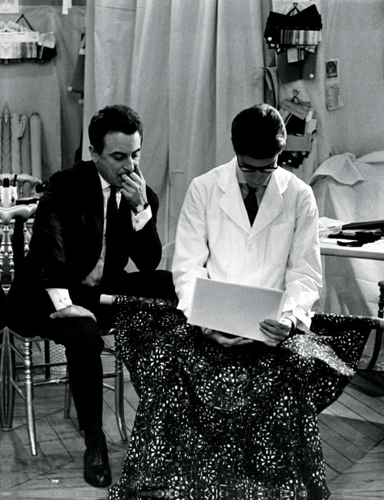

In the Christian Dior salon, wearing his blouse blanche (white coat), Saint Laurent highlights the lines of his “Chicago” jacket. A leather stunner from his final Dior couture collection, the “soft and supple” piece was described by Vogue as “a glossy black crocodile jacket” edged with mink and crocodile bows.

“A GARMENT IS HELD ON BY ITS SHOULDERS AND THE NAPE OF THE NECK. THAT IS THE MOST IMPORTANT PART. THIS IS HOW THE GARMENT IS DRAPED.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

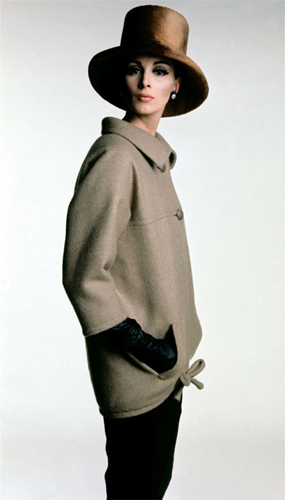

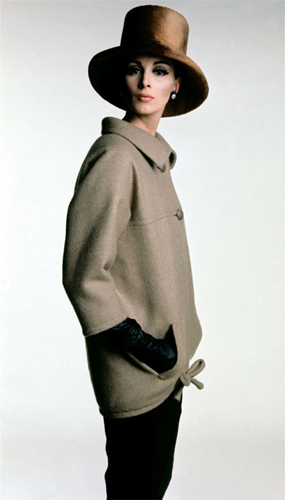

Wilhelmina models a sand-colored wool fisherman’s shirt jacket, an early iconic Saint Laurent couture piece, teamed with a “straight charcoal dress” and “brass beaver hat.” Seeing it as strikingly innovative, Vogue referred to the top’s “wind-ballooned back” and being “knotted saltily at front.” Photograph by Irving Penn, 1962.

Like Vogue’s Michel de Brunhoff and Christian Dior, Saint Laurent’s former mentors, Bergé had an enduring respect for the arts. His passion for poets, writers, artists, and dancers was something that he always shared with Saint Laurent; it was a key and lasting element of their relationship. Although Bergé lacked a formal education—he had left home before obtaining his baccalaureate—propelled by personal ambition, he was determined to better himself. Without either the privilege of Saint Laurent’s upbringing—his father was a tax inspector—or the added advantage of unconditional maternal love (his mother viewed him as “lazy and undecided”), Bergé had only one dream: to flee the provinces and “find freedom” in Paris. After various schemes such as journalism and secondhand book dealing, he started an eight-year affair with the respected and successful artist Bernard Buffet. He had done portraits of Dior and other notables and Bergé promoted Buffet as if he was the new Picasso. The first time Victoire, the model, saw Bergé, she could not believe his gall and pushiness. However, when they eventually became friends, she was seduced by his agile mind and charm.

Bergé and Saint Laurent had met at a dinner given by Marie-Louise Bousquet, the Harper’s Bazaar correspondent, in honor of Saint Laurent. For Bergé, it was un coup de foudre, love at first sight. Bergé was struck by Saint Laurent’s romantic looks and vulnerability. “He was a strange, shy boy,” he told British Vogue’s Lesley White. “He reminded me of a clergyman, very serious, very nervous.” Bergé—a power animal, short and sexually virile rather than handsome—made his presence known at Dior, chatting up Suzanne Luling in the salon and demanding a chauffeur-driven car for Saint Laurent; having been friendly with Monsieur Dior, he was aware of a star couturier’s entitlements. However, Bergé truly came into his element when Saint Laurent was conscripted into the army in the summer of 1960. Saint Laurent reported for military duties and then had a nervous collapse. At first, he was sent to the Bégin military hospital and then incarcerated at Val-de-Grâce’s military hospital, in the south of Paris. This was a torturous ordeal and lasted until mid-November 1960. Crazed types ran in and out of Saint Laurent’s room, while he was put through a series of electric shock treatments as well as being force-fed unnecessarily heavy tranquilizers. When given his leave, Saint Laurent weighed 77 pounds (35 kilos). Although no one was meant to visit him, Bergé forced his way in and managed to get him released from hospital. He also broke the news that Marc Bohan had replaced Saint Laurent at Dior in October.

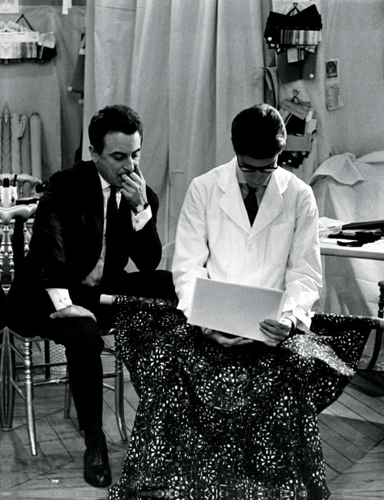

Pierre Bergé, left, and Saint Laurent photographed by Pierre Boulat at their new couture house on rue Spontini. Snared between fittings, the couturier combs through technical details. Understaffed before the first couture collection, Bergé and he had to furiously multitask.

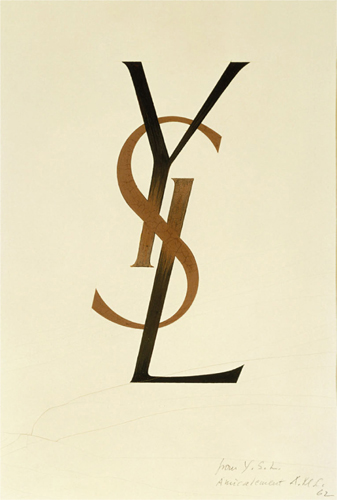

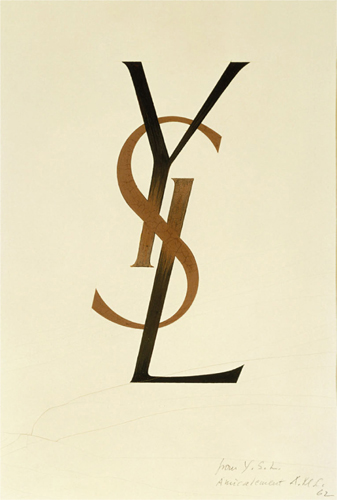

Adolphe Jean-Marie Mouron, professionally known as Cassandre, designed the YSL logotype in 1961. Influenced by cubism and surrealism, Cassandre was known for the boldness of his typefaces, an essential ingredient for the three initials that needed to capture attention and travel the world.

Devastating as the information was, Saint Laurent did not crumble. Becoming quite calm, he famously said: “There is no other solution, we have to open a couture house.” It was bold, and yet another example of Saint Laurent’s tremendous confidence in his own talent. Encouraged by Bergé he sued Dior for breach of contract and won 680,000 francs ($72,665) in damages. Bergé also sold his apartment and a few of his Bernard Buffet paintings. It was courageous, but Saint Laurent had become his passion and cause. The belligerent Bergé turned into Saint Laurent’s guard dog. Promoting and protecting his lover’s talent became a fundamental element of their partnership and gave it its enduring force.

For their office, Bergé rented two rooms on the rue la Boétie in the 8th arrondissement and hired the graphic artist Cassandre to design the iconic YSL logo. Victoire was also taken on board, officially doubling as mannequin and directrice de couture, but really being there to console Saint Laurent and counteract his gloomy, and daily, declarations of “I am done for … I’m finished.” Despite Saint Laurent’s doubts, Bergé’s valiant efforts and tireless networking secured an American backer in the form of Jesse Mack Robinson, a self-made millionaire car dealer from Atlanta. On December 4, 1961, they moved to larger, temporary premises and opened the house of Yves Saint Laurent. The event was marked by an article in Paris Match, which was edited by Roger Thérond, Victoire’s husband. Photographs show Saint Laurent posing in front of bolts of fabric while the former Dior star model, typical for the period, was smoking with one hand and telephoning with another. “The starkness of the setting and the dramatic composition of the photograph express the huge pressure Yves was under to pull the rabbit out of the hat,” wrote Alicia Drake in The Beautiful Fall. Even so, the article stirred interest and was the perfect follow-up to the Paris Match teaser published in August 1961 under the title of “Deux Parisiennes semblent porter du Yves Saint Laurent” (Two Parisians appear to be wearing Yves Saint Laurent) showing Victoire and Zizi Jeanmaire, the famous dancer, who relied on Saint Laurent for her stage costumes.

Pierre Boulat, the French photographer, was hired to record the action prior to Saint Laurent’s very first collection. Boulat caught Saint Laurent “standing, sitting, kneeling, crouching to correct a fabric or drape a length of cloth.” Wearing a plain white cotton coat that prevented distraction, allowing him to focus on the model and the outfit’s fabric, Saint Laurent is in a swirl of action whether spreading out his sketches, checking on the length of skirt, holding up embroidery to an evening dress, trying a hat out on Victoire, and inspecting costume jewelry, via his long tapered fingers. One portrait illustrates his anguish. Seated at his desk with a simple light over his head and the year’s cardboard calendar perched behind his chair, Saint Laurent covers his glasses and face with his hands. Meanwhile, Bergé kept to his office, arranging the launch on January 29, 1962 at an hôtel particulier on the rue Spontini in the 16th arrondissement.

In the salon, no-nonsense wooden chairs replaced the little gold ones so reminiscent of stuffy couture occasions, while the appearance of Helena Rubenstein, the makeup magnate, Jacqueline de Ribes, the society hostess, and Lee Radziwill, the socialite sister of Jackie Kennedy, added to the atmosphere. The collection was judged a hit by Saint Laurent’s friends, such as Jeanmaire and novelist Françoise Sagan, although some felt it was fairly conformist, as it consisted of wool day suits, cocktail dresses, and Raj coats. British Vogue, on the other hand, found Saint Laurent’s suits “surprisingly, unbeat,” drawing attention to the “neat jacket with setin sleeves, a slight concave scoop to the front, cropped to show an inch or two of blouse” and the skirt “wrapped like a sarong with a soft centre fold.” They also mentioned the “stark, nun-like simplicity” of his black dress, made of black soufflé crepe that contrasted with “the ruffles and frilleries” viewed at Lanvin, Laroche, and other French fashion houses. And Vogue across the Atlantic referred to “beauties … that will surely be seen at elegant parties in New York, Paris, London, Rome—over and over again.”

Saint Laurent’s plaid wool and gold buttoned suit with, said Vogue, “small pointed collar … sleeves mounted low and squarely,” photographed by William Klein in 1962. It displayed the conventional approach, apparent in his early collections; a modern element offering mild contrast was “the tied leather belt.”

The day after Saint Laurent’s show, couture clients had rushed in, ordering six or seven outfits. The first person was Patricia Lopez-Willshaw who chose a jet-encrusted evening gown. This was a serious compliment; Lopez-Willshaw was a recognized international grande dame of fashion, noted for wearing Schiaparelli and Dior. Her confidence in Saint Laurent would inspire others to follow suit.

In the Parisian haute couture world of the early sixties, society played a key element; hostesses could encourage interest in designers by inviting them to their homes. Since Bergé and Saint Laurent knew les règles du jeu (the rules of the game), were cultured and au courant, they became socially in demand. What is admirable about Bergé and Saint Laurent is that they never hid their homosexuality, during an era when many others in fashion did. And their bohemian attitude and lifestyle attracted Parisian powerhouses like Marie-Hélène de Rothschild, the wife of a millionaire banker; Hélène Rochas, the exquisite widow of Marcel Rochas who ran his fragrance empire; and Charlotte Aillaud, the sister of Juliette Gréco and the wife of a prominent architect. The erudite Bergé knew how to flatter and was skilled at presenting Saint Laurent as the new “boy genius” in the fashion world, and the charismatic designer played the role to the hilt. At ease in female company, he quietly charmed women with his good looks and intelligent observations about their appearance.

Vogue presented “Yves Saint Laurent’s dress and pullover partnership” on Jean Shrimpton, photographed by David Bailey in 1963. Suggesting future flair, the “dead simple” fitted wool jersey dress with short sleeves and “curled collar” contrast with the roomy, sailorlike tweed top.

Saint Laurent and Bergé also won over key members of the media. John Fairchild, then running Women’s Wear Daily, was smitten, as was the New York Herald Tribune’s Eugenia Sheppard and Diana Vreeland, who would join Vogue later that year. Recalling her first meeting with Saint Laurent, Vreeland described, “a thin, thin, tall boy” who was “something within himself … He struck me right away as a person with enormous inner strength, determination … and full of secrets. I think his genius is in letting us know one of his secrets from time to time.”

Saint Laurent’s designs grew more confident and youthful with each season. Vogue referred to his second collection as “a glittering tour de force, greeted with the special kind of emotional fervor reserved for such occasions.” He introduced a chic softness, tiered dresses, and tunics with easy sleeves and bold buttons as well as thigh-high boots. Fairchild referred to his 1964 fall/winter show as “the most beautiful collection” he had ever seen in Paris, “marking the return to gracious, refined clothes.”

Then, in the summer of 1965, Saint Laurent unveiled his Mondrian collection. In this iconic collection, Saint Laurent used reproductions of the Dutch artist’s paintings on straight jersey dresses. Cutting a sharp, modern figure, with its excellent use of abstraction, perfect proportions, and choice of crisp white jersey, the Mondrian dress was hailed as the dress of tomorrow. The Mondrian made the Vogue Paris September cover—a first for Saint Laurent’s fashion house—and Vogue photographed the hit dress on the long limbs of Veruschka, the German supermodel. “Contrary to what people may think, the severe lines of the paintings matched the female body very well,” Saint Laurent later said. The Mondrian dress—an unforgettable classic—typified his scene-stealing designs by being both eye-catching and flawlessly executed.

Described as “Saint Laurent’s schoolgirl” Shrimpton proves the ideal candidate for his double-breasted couture lace-tweed suit, enhanced by straw boater, gloves, and cravat. The entire look demonstrated the influence of Chanel, a couturier whom he admired and emulated. Photograph by David Bailey, 1964.

Saint Laurent’s Mondrian couture dress was his first design to have instant international appeal. Vogue mentioned the “jersey rectangles,” the “blocks of color laid on like fresh paint,” and the “elongated proportions.” “Bottle the spirit of this collection and label it Y—as in yummy-new-perfume.” In a legendary session, it was photographed on Veruschka by Irving Penn in 1965.

“THE MASTERPIECE OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY IS A MONDRIAN.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

Italian movie star Elsa Martinelli wears Saint Laurent’s couture gown that exposes the waist, and a fishnet white wool cape, a youthful and relaxed ensemble described by Vogue as “a perfect way of wearing an evening coat and showing a dress at the same time.” Photograph by David Bailey, 1965.

The simple design also caught the mood of the moment by defining an effortless elegance. Perhaps 1950s’ couture clients wanted to enter the room in their Balenciaga gown, secure in the knowledge that “no other women existed,” to quote Vreeland; but such thinking began to be dismissed as old-fashioned in the 1960s. The international set had, for example, discovered the luxury ready-to-wear designs of Emilio Pucci, the Italian aristocrat. Pucci’s clothes, in his silky proto-psychedelic fabrics, were sensual and relaxing, rather than stiff and formal. And Saint Laurent’s infamous antennae picked up on that change, the movement toward clothes that were easy to wear; yet with his innovative skill, and his designs made seamless by apt proportions, choice of fabric, and of color, managed to deliver something different and uniquely stylish—and unexpected—that women longed for. “When a dress of Yves Saint Laurent’s appears in a salon or on television, we cry for joy,” wrote Marguerite Duras, the French novelist. “For the dress we had never dreamed of is there, and it is just the one we were waiting for, and just that year.”

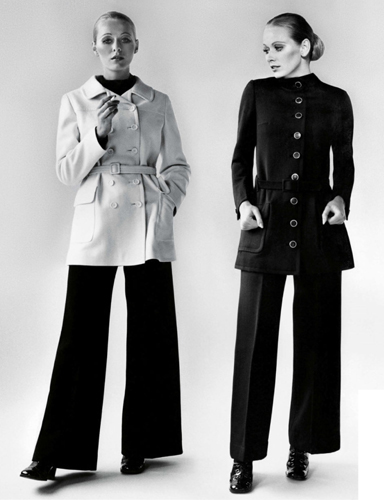

In Saint Laurent’s 1966 spring/summer collection, he included a navy pea coat. It was a design first viewed in his premier collection and, in its tailored transformation of the outline of a working man’s coat by graceful cutting and fitting of the armholes and attention to the length and fall of the jacket, it would become a classic. However, Le Smoking from the following collection would transcend everything. In the style of men’s formal eveningwear, Saint Laurent produced an ensemble that had jackets and pants of black wool grain de poudre piped with black satin along the pant leg, worn with frilled blouse and black satin ribbon tie. It was a sensation, and the first time that a French male couturier introduced menswear and an androgynous style into his collection. Six months later, he provided the pant suit, further pushing the message. “There is no reason for me to dress women differently from men,” he said in 1971. “I don’t think a woman is less feminine in pants than a skirt.” And in Saint Laurent’s designs, with the elegant lines of the jackets, cut to emphasize the femininity of the throat, the waist, and the wrist, and pants tailored so as to lift the behind, they were never masculine.

Indeed, Saint Laurent’s idea was that pants gave “a base that would be changeless, for a man and a woman.” “It was absolutely a conscious choice,” he told Vogue’s Joan Juliet Buck. “I’ve noticed that men were surer of themselves than women, because their clothes don’t change—just the color of the shirt and tie—while women were a little abandoned, sometimes terrified, by a fashion that was coming in, or fashion that was only for those under thirty.” Nevertheless, Saint Laurent cautioned against a mannish look even if he cited “a photograph of Marlene Dietrich wearing men’s clothes” as his chief influence. “A woman dressed as a man must be at the height of her femininity to fight against a costume that isn’t hers,” he continued. “She should be wonderfully made-up and refined in every detail.”

Putting women in pants modernized their closet but, in the late 60s, caused a revolution. Nan Kempner, the American socialite and style icon, was barred from entering a Manhattan restaurant owing to her Yves Saint Laurent pant suit. Not missing a beat, the greyhound-slim Kempner took off her pants and appeared in her tunic, which now became an ultramini dress.

Catherine Deneuve, the French actress who wore Saint Laurent in Buñuel’s classic movie Belle de Jour, described him as designing for women “with double lives.” “His day clothes help a woman confront the world of strangers,” she wrote. “They permit her to go everywhere without drawing unwelcome attention and, with their somewhat masculine quality, they give her a certain force.” Deneuve also referred to “an immediate sensual experience” when wearing Saint Laurent’s couture clothes. “Everything, no matter what it’s made of, is always lined in silk satin,” she wrote. “That detail is emblematic of his total attitude toward women. He wants to spoil them, to envelop them in the pleasure of his clothes.”

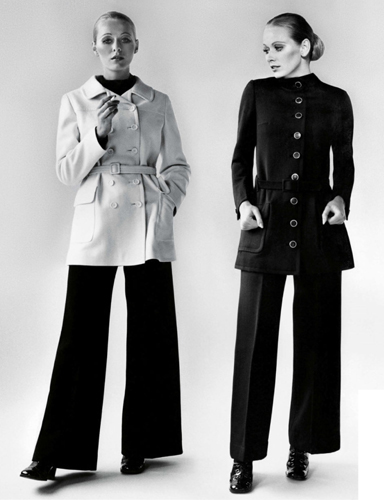

Maudie James models two kinds of Rive Gauche suits offering sleek and straight pants with hems that widen. Although Saint Laurent would empower a woman and transform her closet with pants, the idea was initially viewed as scandalous. Photographs by Normal Eales, 1968.

Models Donyale Luna and Moyra Swan wear short couture “barely there dresses” termed as “transparent magic”. Popular cover girls, Luna and Swan were ideal to promote Saint Laurent’s youthful chic and zest.

Luna wears Saint Laurent’s strikingly modern “Moonstruck t-shirt” dress. Photographs by David Bailey, 1966.

Three examples of Saint Laurent’s woven “Hypnotic effects” photographed by David Bailey in 1966. From left, a navy-and-white pullover dress, a cobalt-and-white reefer coat, and a black-and-white suit with square-necked jacket worn by Donyale Luna. When experimenting, Saint Laurent kept to classic and wearable colors.

“HE UNDERSTOOD THAT FASHION HAD TO EXPLORE NEW HORIZONS.”

PIERRE BERGÉ

The silk for this art-nouveau-inspired couture dress came from Gustav Zumsteg’s Zurich-based Abraham fabrics, recognized for its bold prints and profound influence on Saint Laurent. Photograph by William Klein, 1965.

David Bailey’s 1967 Vogue cover demonstrated Saint Laurent’s vitality and love for vibrant colors, evident on his couture bandanna scarf and gabardine trench coat.