“I WAS TORN BETWEEN THE ATTRACTION OF THE PAST AND THE FUTURE THAT URGED ME FORWARD.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

A STYLE REVOLUTION

A

For Yves Saint Laurent, a couturier who wished that he had invented denim blue jeans, launching Rive Gauche, his ready-to-wear line, made sense in 1966. It also fitted into the 30-year-old’s mood. He had become the fashion world’s hip young prince and was “sick to death of the couture,” and its old-fashioned dictates. “Yves Saint Laurent understood his time,” said Pierre Bergé. “He wanted to democratize his metier, which was aristocratic, up to then.”

An event in the Ritz Hotel concerning Coco Chanel, the old guard, and Saint Laurent, the new one, illustrated this. He was lunching with Lauren Bacall, the leggy style icon and Hollywood actress, who was sporting a mini skirt. Chanel, who famously hated knees, was appalled. “Saint Laurent, never do short skirts,” she croaked. But Chanel had misjudged the formerly shy young man. Saint Laurent had become assertive in his craft and had seriously loosened up in the sixties. Rules and exclusivity in fashion seemed old hat and fusty and he was excited by the new spirit of liberation and equality. For someone who lived a privileged existence and depended upon Bergé, who organized everything in his daily schedule, it was interesting that Saint Laurent was so stirred by the sixties. Putting it down to his acute antennae or sensitive nose that scented change, he told Vogue’s Barbara Rose, “I think my success depends on my ability to tune in to the life of the moment, even if I don’t really live it.”

Saint Laurent Rive Gauche Prêt-à-Porter, the line’s official name, was the designer’s mission from the beginning. According to Bergé, he resented the “injustice” of the French fashion system that only focused on and favored wealthy women and ignored an entire generation of women who could not afford couture. “Yves formed a new relationship between the fashion creator and the client,” said Bergé, suggesting that fashion no longer had to be “an ivory tower existence” concerning those who stayed “at the Ritz.” And with the opening of the Rive Gauche boutique, Saint Laurent offered a challenge to the haute couture world and, to quote Bergé again, “became the first ever couturier with a prominent name to create a boutique selling ready-to-wear.”

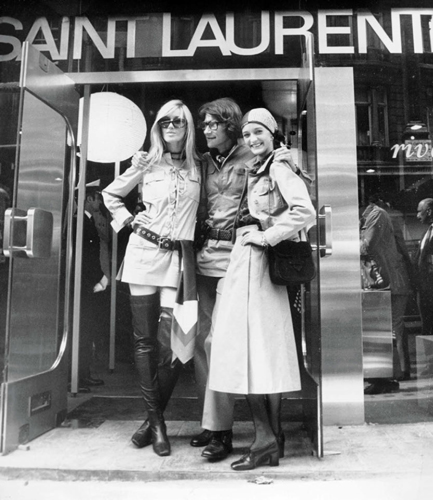

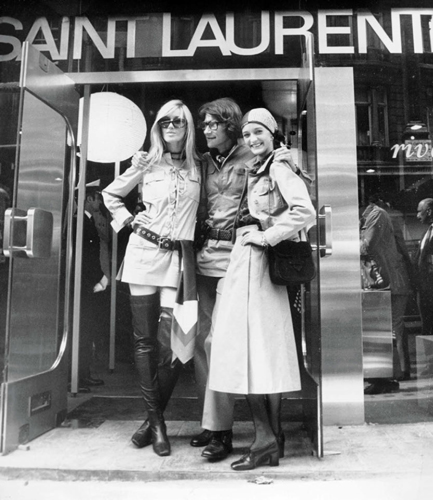

At the London opening of his Rive Gauche boutique in 1969, Yves Saint Laurent is flanked by his two muses: Betty Catroux, wearing his iconic “safari” jacket, and Loulou de la Falaise in signature bohemian attire. As predicted by Vogue, his ready-to-wear line proved an immediate success.

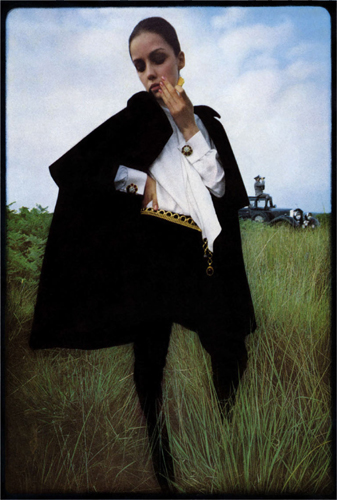

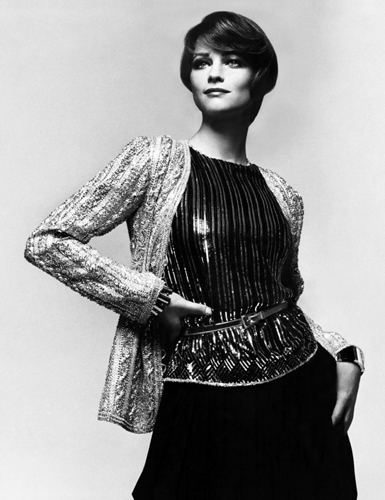

Saint Laurent embraced the miniskirt and the zeitgeist of the 1960s. Nicole de Lamargé models Saint Laurent’s black leather couture suit whose details include black mink edging the short Hussar jacket and a wide hip-level belt. The black patent boots were by shoe designer Roger Vivier, Saint Laurent’s close collaborator. Photograph by Brian Duffy, 1966.

The actress Catherine Deneuve, photographed in Rive Gauche—a corn-yellow quilted cotton dress with black lace around the hem—by her then husband David Bailey in 1967.

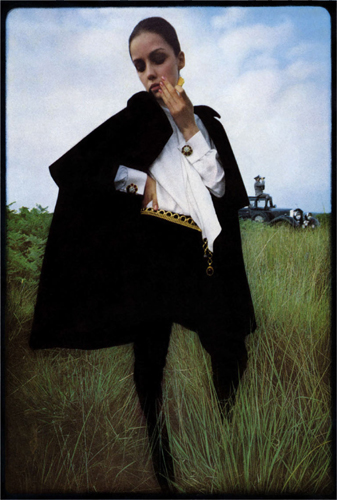

“Bold, Byronesque,” and “dashing” were Vogue’s terms for this velvet cape and knickerbocker Rive Gauche suit. Adding a white shirt and a considerable amount of his “gilded chain belts” gave it Saint Laurent’s Parisian allure. Photograph by Jeanloup Sieff, 1967.

It was a risk. “We had no business plan,” recalled Bergé. Yet Rive Gauche, viewed as fashion for the street because of its relatively reasonable prices, was to lead to the full flowering of Saint Laurent’s talent as well as empowering him beyond his wildest dreams. Vogue’s Gerry Dryansky recalled how, outside of France, “Fashion had burst out into a sort of worldwide citizen’s band: everybody’s clothes were calling out—proclaiming values, politics, foisting dreams, and invitations.” In Paris, Chanel and Balenciaga “turned their backs on all that and died disgusted”; Hubert de Givenchy “kept on dressing his moneyed clients”; whereas André Courrèges “bravely created an original style” between Barbie and Buck Rogers that “reinvented the mood” and lasted for “about two years.” However, it became Saint Laurent’s hour. His “eclectic, empirical desire to transform the street’s own ideas into something similar, better, touched by genius proved the triumphant form of modernism,” Dryansky wrote. To quote Marella Agnelli, one of Saint Laurent’s famed couture clients, Rive Gauche created “the look” of the times and “fashion took a big step into the future, leaving behind the remote, elitist character it had had in the past.”

“It is important for the boutiques to have less expensive clothes so that young women may buy them.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

A

In Diana Vreeland’s estimation, Saint Laurent would have “a fifty-fifty deal with the street.” “Half of the time, he is inspired by the street and half of the time, the street gets its style from Yves Saint Laurent,” she wrote. “His vehicle to the street is prêt-à-porter—but behind it all are the superb designs of his couture workroom.” The couturier would actually keenly separate “church”—haute couture—and “state”—ready-to-wear. “It would be impossible to copy (haute couture) designs in ready-to-wear,” he told Vogue’s Rose. “No matter how much I might want to at times, the handiwork could not be duplicated by machines. For that reason, I conceive of the prêt-à-porter designs differently in times of machine fabrication.” Still, as “The Saint” was quick to emphasize, “there is the same will to perfection” and he gave himself “entirely” to ready-to-wear as he did to couture. His gift for seamlessly shifting between the two worlds also offered another angle to his genius. With his legendary taste and eye that missed nothing, Saint Laurent knew how to create hits for couture—elegant attire that conformed to the racing world and shooting weekends—and hits for ready-to-wear—pieces that suited a café lifestyle and could be worn clutching a boyfriend on the back of his motorbike.

Clara Saint, a beautiful Chilean socialite with international connections, was hired for Rive Gauche’s public relations. (A curious aside, but like Saint Laurent’s mother, the doll-like Saint was red-haired and green-eyed.) “When Yves decided to create Rive Gauche, he wanted a small out-of-the-way boutique,” she recalled. Hence the choice of rue de Tournon, an address in the 6th arrondissement lying on Paris’s left bank, the rive gauche. “It was young, subversive … [and] had an ‘intellectual’ connotation,” she continued. However, reflecting Saint Laurent’s overprotected existence, he presumed that impoverished students from the Sorbonne and other establishments would snap up his clothes, when Rive Gauche would hardly come near Monoprix prices.

Saint Laurent used Abraham’s panne velvet fabric, resembling, said Vogue, “liquid mother-of-pearl shadowed with roses in seashell colors,” for a long evening dress that is romantic and seductive. Photograph by David Bailey, 1969.

Saint Laurent’s mastery of color and pattern appeared equally in his couture and ready-to-wear. David Bailey photographs Susan Murray and Maudie James in 1969 in his elaborately constructed long couture gowns in jewel colors of flower pattern and patchwork.

Ingrid Boulting adds a flower-child look modeling a Rive Gauche shawl and scarf in a graphic flower print. Photograph by David Bailey, 1970.

Nevertheless, when Rive Gauche opened its doors on September 26th, there was a stampede. Saint recalled the 1940ft2/180m2 boutique being crammed with beauties frantically trying everything on. The appearance of the 23-year-old Catherine Deneuve in a navy blue pea coat made quite an impression on customers queuing down the street. The styles caught the spirit of the youthquake (as Diana Vreeland dubbed the sixties fashion and music revolution) yet added another element: chic. Rive Gauche would further the Parisian’s reputation for being chic just as Chanel had, with her little black dress, suit, and bag.

Talking to Vogue’s Joan Juliet Buck, Saint Laurent described fashions as being the vitamins of style. “They stimulate, give a healthy jolt … wake you up,” he said. And the vim and vigor of his Rive Gauche designs began to spring off the pages of Vogue. In the March 1968 issue, the socialite Charlotte Simonin, is photographed around Paris, wearing a series of youthful looks such as a short gray flannel suit, set off by a military collar and kilt-style skirt, and a flouncy black-and-white chintz dress. Parisian in attitude, her long hair and bangs are unkempt while she wears white socks on her long, coltish legs. Six months later, young dynamic Americans such as Tina Barney, Justine Cushing, and the actress Paula Prentiss are photographed in Saint Laurent’s wide pants, culottes, and shift dress. Nevertheless, one image eclipses all others, in American Vogue’s September issue of 1968. Under the title “Saint Laurent is here!! In New York!!” Diana Ross, caught in Grand Central Station, defines what dazzling means, in flowing tunic top and slithery black chiffon velvet pants, cinched at the waist with a knotted patent leather belt. As if caught in mid-dance, she opens her arms, wide and welcoming. The lead singer of The Supremes, she was black and beautiful, and the spontaneous shot sent an important message: Rive Gauche was for everyone in the United States.

Yet another Vogue fashion shoot featuring the very blonde model Betty Catroux and the dark-haired singer and actress Jane Birkin unveiled the four-page “Saint Laurent Rive Gauche report.” The jersey pant suit with “long line” tunic, shirtdress, and double-breasted wool coat were effortlessly elegant and fit Dryansky’s description of Saint Laurent’s clothes as “stockpiles in times of famine.”

Diana Ross, “the gorgeous star of The Supremes,” was also a dedicated follower of fashion. At the New York launch party of Rive Gauche, she radiated charismatic glamour in black chiffon velvet pants and tunic top. Photograph by Jack Robinson, 1968.

Actress and model Jane Birkin enhances Rive Gauche’s bohemian allure in a black shirt and wool carpet kilt in a brown and cream stamped patterning—the season’s bestseller—that displays classic Saint Laurent style. Photograph by Patrick Lichfield, 1969.

When Rive Gauche opened in London in 1969, Birkin was photographed for British Vogue by Patrick Lichfield, wearing Saint Laurent’s white silk ruffled shirt, charcoal and brindled sweater, an ikat-patterned kilt, and a black crushed-velvet suit. “Inimitable looks and individual things,” enthused the accompanying text, referring to a range that included “silk scarves dipped in pure paint,” “silk tasselled cords,” and a palette offering “aubergine, dusky pinks, deep purples, and scarlet.” Clare Rendlesham, a former fashion editor, opened the Rive Gauche boutique in Bond Street. “The clothes were amazing: lots of long denim skirts, lace-up safari jackets, long lace-up boots,” recalled Jaqumine Bromage, Rendlesham’s daughter. The clothes were “advanced and twice as expensive as the other London boutiques like Biba,” but gradually women returned, aware that “it was worth paying more for the quality.”

To launch London’s Rive Gauche boutique, Saint Laurent showed up in the company of Catroux and Loulou de la Falaise. Cool in sunglasses, Catroux was wearing the iconic safari jacket daringly teamed with thigh-high leather boots, while the smiling de la Falaise, who covered her head with a scarf, chose a denim-style jacket, midi skirt, and suede shoulder pouch. Later described as Saint Laurent’s muses, they represented the contrasts of his styles. Catroux played the stark, tomboy role whereas de la Falaise, with her flair for color and accessories, was a sort of flawlessly flamboyant bohemian.

“My success depends on my ability to tune in to the life of the moment.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

A

Catroux had met Saint Laurent in 1966. “He picked me up in a night-club,” she recalled. “We both had long pale blonde hair, were both very thin, and were both dressed in black leather.” Being “sensitive to the same things,” they became best friends. The only daughter of Carmen Saint, one of Christian Dior’s Brazilian haute couture clients, the chiseled and Nordic-looking Betty had been a house model for Chanel. In 1967, she married interior designer François Catroux, a childhood friend of Saint Laurent. Androgynous and mysterious-looking, Betty was exceptionally bright but preferred to hide her intelligence behind a “I-do-nothing,” unambitious façade. Betty was into being young and embracing youth culture and, thanks to her influence, so was Saint Laurent. He questioned whether he really needed to tolerate stuffy couture clients anymore. Surely he was famous enough to cut these ties? Catroux and he would giggle for hours and dance together to the latest pop records. When Saint Laurent had black moods, Betty understood and would commiserate. In spite of her pose, the supposedly sauvage Madame Catroux was kind and loyal, which Saint Laurent needed. Women were there to prop him up or adore him just as his mother Lucienne had.

Loulou de la Falaise was also generous and faithful but quite different. Half-English, half-French, she was the daughter of Maxime Birley, the model and society beauty, and Alain, Comte de la Falaise. De la Falaise’s childhood had been horrific: after their parent’s divorce, she and her younger brother Alexis had been fostered by a series of abusive couples but, unlike Saint Laurent who continually referred to his miserable schooldays and blamed his time in Val-de-Grâce military hospital for his delicate psychological state, de la Falaise kept a stoic silence about her painful past. A woman of substance with a refined taste in fashion, she had been a junior fashion editor at London’s Harper’s & Queen, designed prints for Halston, the fabled American designer, and modeled for American Vogue’s Diana Vreeland.

Yves Saint Laurent and Betty Catroux, photographed by Henry Clarke in 1972, having fun in his favorite room, the library, a white room filled with books, 17th-Century Chinese figures, and Lalanne sheep. Both shared a healthy sense of the absurd, while the designer viewed Betty as his physical female equivalent.

“SAINT LAURENT CAPTURED THE ZEITGEIST WITH UNCANNY ACUITY.”

HAMISH BOWLES

Saint Laurent photographed by Bruno Barbey in 1971 surrounded by models from his 1940s-inspired spring/summer show, later referred to as la Collection du Scandale. Though controversial and criticized, the use of fur, exaggerated sophistication, and heightened feminine proportions ended up being extremely influential.

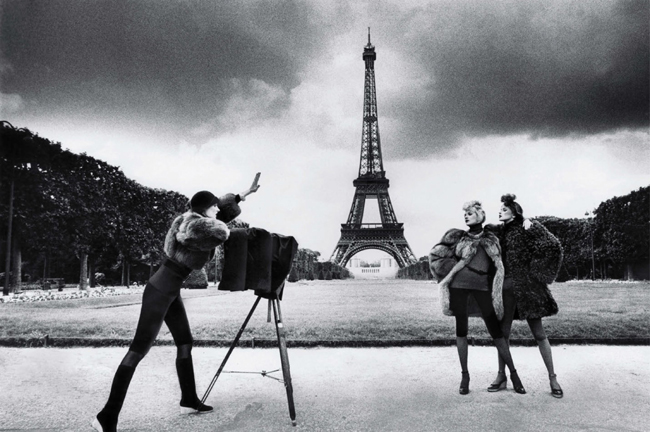

Grace Coddington, who styled the shoot, pretends to photograph two models including Louise Despointes; they wear a dyed-red fox bolero, a lime three-quarter length fox jacket, and an emerald-dyed fleecy lamb’s wool jacket, from the 40s Collection. “They can wear their furs just as well over evening dress or a skating skirt and perched on high crepe wedges or Allen Jones heels,” advised Vogue. Photograph by Duc, 1971.

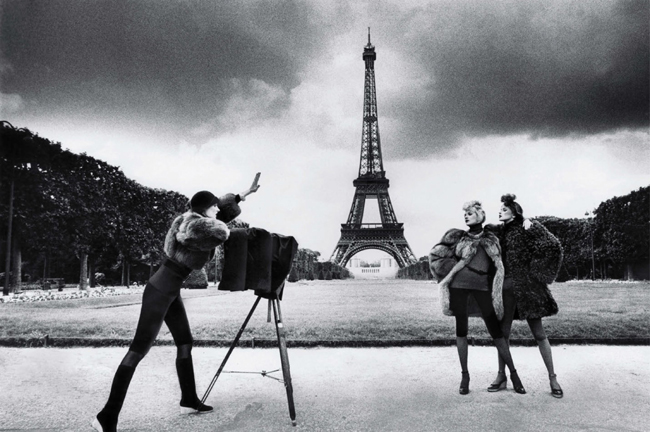

“IT’S TO DO WITH BEING HERE, THE ENERGY AND DYNAMISM OF PARIS.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

Saint Laurent explored the color and sensual potential of knits as thoroughly as with other materials. Described as “patched, flowered, striped, and plaid,” a signature Rive Gauche mood is captured by a printed silk shirt, belted tank top, and printed skirt. Photograph by Barry Lategan, 1971.

Saint Laurent had been transfixed by de la Falaise when they first met, through Fernando Sánchez, a classmate from his Chambre Syndicale fashion school. A free spirit, she seemed to sum up spontaneity and yet sophistication, too. Their 1968 courtship began with Saint Laurent sending her a mix of couture clothes and Rive Gauche designs—de la Falaise instinctively knew how to marry styles—and then he offered her a position in his studio which she finally accepted in 1972, joining the more reserved Anne-Marie Muñoz, who ran the studio. Muñoz had met the couturier during his tenure at Christian Dior. Well organized and extremely respectful, her chief aim was to “please Yves.” De la Falaise, on the other hand, had her point of view and was prepared to argue with Saint Laurent. He would always admire her honesty and exuberance. “She is a sounding board for my ideas,” he told Vogue’s Mary Russell. “I bounce thoughts off her and they come back more clear and things begin to happen.”

A year before employing her, he invited de la Falaise to his infamous 1971 collection; this had been inspired by Paloma Picasso, whom Saint Laurent recalled seeing at an event “in a turban, platform shoes, one of her mother’s 1940s dresses, and outrageously made up.” Seated next to Picasso, Loulou had her hair in ringlets and was wearing a bright pink Saint Laurent satin jacket and purple shorts. They were put in the audience, in order to talk about the show afterward and demonstrate support. Clearly, Saint Laurent was nervous about the collection: it was different from his other couture shows and nothing like anything else in fashion, at that time. After a lineup of 1940s-style dresses with plunging necklines, seen under fur chubbies (short, chunky fur coats) in green and blue, were designs like a velvet coat covered in lipstick kisses, large velvet turbans, puffed sleeves, ruched waists, and wedge heels. The louche styling of the models appeared shocking. Their lips were smeared with lipstick and it was evident that none was wearing underwear, particularly a voluptuous model whose large breasts bounced freely under her red dress. Eugenia Sheppard denounced the experience as “completely hideous.” Nor did any of the French audience approve. It was generally felt that referencing the 1940s brought up shameful memories of France under the Occupation.

Vogue’s enthusiasm for Rive Gauche continued throughout the 1970s: “Take home more Saint Laurent looks—like his dressed up shorts … Adore his new classic cardigans and pleats.” Photograph by Peter Knapp, 1972.

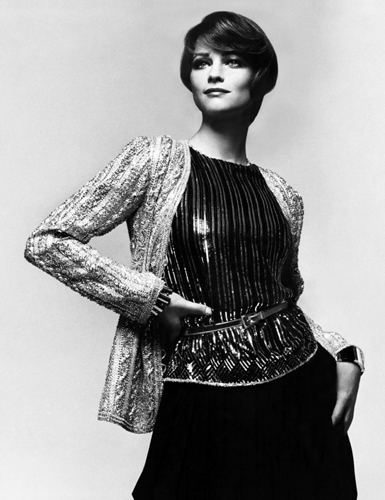

Charlotte Rampling, another British model-turned-actress, suited Saint Laurent’s effortless elegance. Here, she wears his couture cardigan, which Vogue, despite its glamour, called “a poem of understatement,” a glittering top, and navy blue skirt. Photograph by David Bailey, 1972.

A chef d’oeuvre, the black-satin detailed Le Smoking was easy to dress up – with fur, for example – or down. Photograph by Peter Knapp, 1971.

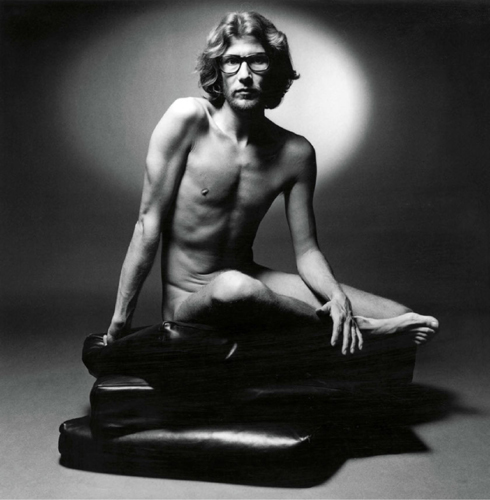

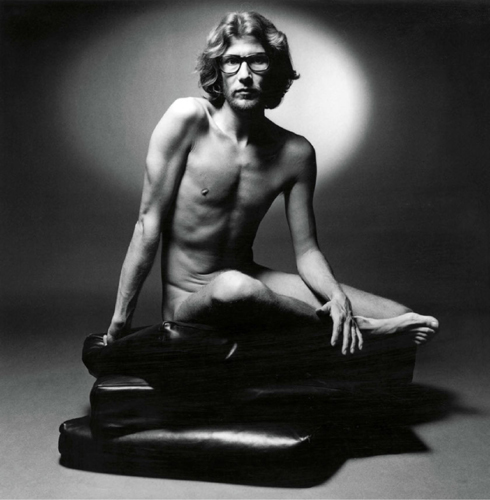

Jeanloup Sieff’s portrait of Yves Saint Laurent, used to advertise the designer’s YSL aftershave in 1971, was groundbreaking on several fronts. It was the first time in fashion history that a fragrance maker had posed for his own advertising campaign, and Saint Laurent opted to do so in the nude.

Eighteen months later, Saint Laurent told Vogue’s Mary Russell that the collection, which had proved successful and influential, was his reaction to the fashion landscape: “The gypsies, all those long skirt and bangles on middle-aged women in town—in the middle of the twentieth century!” He claimed that it was “a humorous protest” except it was taken seriously. “People thought it wasn’t ‘Me’ but it was; they don’t know about my reactions. I am quiet but inside there is an explosion.”

Saint Laurent’s “explosion” was apparent when he launched his first male fragrance in 1971 and used his own naked self in the advertising campaign. “He wanted to create a scandal,” said Jeanloup Sieff who took the black-and-white portrait. Indeed, the controversial image was Saint Laurent’s idea not Sieff’s. Justly proud of his trim and taut physique, there was also a Christlike look about Saint Laurent who then had midlength hair and a beard. Did he view himself as fashion’s savior? Many women thought he was.

In the early 1970s, there was a sense that Saint Laurent had arrived at a relatively tranquil and confident moment in his life. “After more than ten years as a designer, I now know exactly what to do. I cannot deviate from my style,” he told Vogue’s Russell. “I have made my experiments and mistakes. Now I am sure. Style consists of very little. You don’t go too far to the left or too far to the right.”

In his heyday, the main secret behind Saint Laurent’s style was that everything he designed seemed alluring and apt. Nicknamed le maître (master) by Parisians, it was because they could rely on his designs, whatever the occasion. Empowered by his faultless proportions, bold color sense, and use of sensual fabrics, women felt feminine and seductive. During the day, it might be structured pant suits softened by a satin blouse with pussycat bow or dresses that subtly enhanced the figure. At night, he either created little black dresses or Le Smoking-type suits that glowed with glamour, or wildly embellished pieces that dominated by dazzling.

Many friends put his confidence and tranquility down to his discovering Marrakech and buying a house there in 1967. Called Dar El Hanch—meaning house of the serpent—it was in the ancient medina. “Here he spends three months of every year,” enthused Vogue. “December and June when he prepares his collections, and August, when he relaxes.” Invisible from the street behind its heavy, nail-studded door and thick walls, the house inside was secluded and enchanting. It meandered up and down whitewashed staircases, around a shady inner courtyard with a fountain, out onto vine-wreathed balconies, and up to a flat roof overlooking the palm-fringed city.

There were elements of Marrakech that reminded him of his childhood in Oran; this was perfect for an individual obsessed with nostalgia and the novels of Marcel Proust. There was also a romance to the place that appealed to his aesthetic sense. “On each street corner in Marrakech, you encounter groups that are impressive in their intensity,” he told Laurence Benaïm, his original biographer. “Men and women, where pink, blue, green, and violet caftans mingle. These groups look as if they have been drawn and painted … by Delacroix.” To quote Betty Catroux during that period, “Paris is the mirror of anxieties. Marrakech is the place where he is happy.”

“Oran as a child during the war marked me … in Marrakech I found the climate of my childhood.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

This exotic shoot by Duc in 1976 captures Marrakech’s influence on Rive Gauche’s collection, described by Vogue as having “wrapped knotted heads, harem pants, belts of vivid silk thread.” Naturally, Saint Laurent’s accessories were luxurious and included metallic gold turbans, and ivory bead necklaces.