“ALL CREATIVE WORK IS PAINFUL

AND FASHION IS VERY, VERY DIFFICULT.

IT PLAYS ON ALL MY ANXIETIES.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

THE HOUSE THAT YVES AND PIERRE BUILT

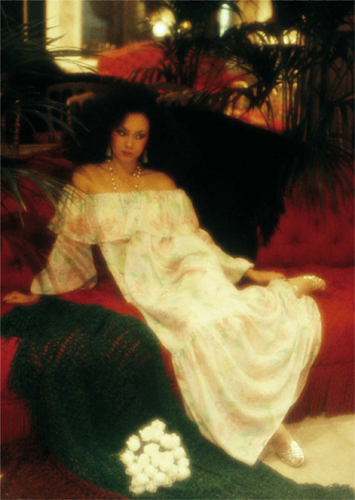

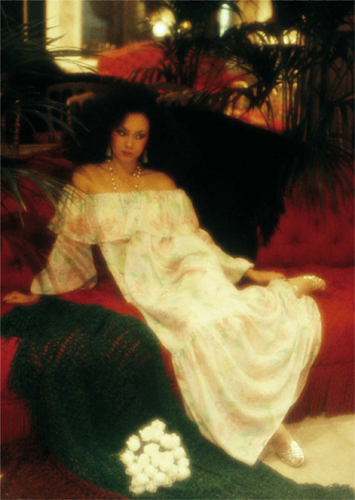

The graceful Bianca Jagger and Saint Laurent had a special affinity, eternally marked by the unforgettable white Saint Laurent couture suit she wore to her wedding. Here she is photographed in Paris by Eric Boman in 1974 wearing a long chiffon and elastic cocktail dress.

A

The 1970s evolved into the glory decade for Yves Saint Laurent. Women exuded sensuality in his clothes, as exemplified by two portraits in British Vogue. Catherine Deneuve is stretched out on the designer’s couch, wearing a gray pinstripe gabardine pant suit and strict silk blouse, whereas Bianca Jagger, the rock star’s wife, is spread across her bed at the mythic left bank L’Hôtel, wearing a long fuchsia pink chiffon dress, black hose, and diamanté peep-toe sandals.

That Saint Laurent could produce so perfectly such contrasting styles, the disciplined and the indulgent, explained why key fashion editors and important retailers hungered for Saint Laurent’s couture and ready-to-wear shows, viewing them as the main event. “If my clothes are right, and I believe they are,” he told Joan Juliet Buck, “it is because I think I understand what women want.” Adding to his triumphs was the success of his Rive Gauche Pour Homme line, which the designer had originally started because he could not find clothes for himself. Two years later, it boasted eclectic clients like actor Helmut Berger, ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev, and playwright Harold Pinter. Further fame came from the fabled Saint Laurent lifestyle that he officially shared with Pierre Bergé and consisted of homes in Paris, New York, Manhattan, Marrakech, and a chateau in Normandy.

There was also the personal charisma of Saint Laurent, who had acquired iconic status, unusual for a fashion designer. He had become as famous as Andy Warhol and Mick Jagger. L’Amour Fou, the Saint Laurent documentary, unveils a short black-and-white home movie that shows these three individuals in each other’s company. Filmed at the designer’s apartment in the rue de Babylone, noted for its Jean-Michel Frank interiors, a longhaired Jagger in tracksuit is hunched over the Ruhlmann piano, tinkling at the keys. Warhol in blazer and jeans, seated on an armchair, opts to smile but remain mute. It is very much Saint Laurent’s moment. Wearing a suit and bow tie, he smiles and camps it up for the camera, enthusing about his series of mini Warhol portraits.

A

“YVES SAINT LAURENT IS ALL ABOUT EXPRESSION. SOME DESIGNERS DO CLOTHING THAT IS MERELY COLOR AND SHAPE, HIS ALWAYS SAYS SOMETHING.”

CATHERINE DENEUVE

Exemplifying the “fire-behind-the-ice” Parisian bourgeois beauty that inspired the couturier, Catherine Deneuve was always a stalwart “Yves” friend and client. Here she sports a couture gabardine pinstripe pant suit with caramel silk shirt. Photographed in Saint Laurent’s apartment by Oliviero Toscani in 1976.

Whatever the occasion, women confidently depended upon Saint Laurent’s Rive Gauche in the 1970s. Under Vogue’s title, “Are you huntin’, shootin’, fishin’ clothes?” Norman Parkinson photographed this suggested outfit in 1973, the cloak, jacket, and skirt in traditional loden, soft suede, and tweed.

Saint Laurent was having a second lease of life, fueled by his roaring career and a lack of inhibition via his discovery of casual sex, recreational drugs, and hard alcohol. One of the designer’s chief complaints was that he had missed out on his youth owing to early fame and his responsibilities at Christian Dior. However, because of the atmosphere of Paris in the 1970s—a sizzling and decadent period—Saint Laurent found the excuse to self-indulge on a monumental scale. Being compulsive, he tended to go too far, though instinctively he knew that Bergé was ready and waiting to save him. Whatever the situation—even if Saint Laurent crashed his car because of a lover’s tiff with a toy boy—he could rely on the highly competent Bergé to sort it out. In the drama, passion, and dynamics of their liaison, which affected and occasionally emotionally drained their immediate circle, the Saint Laurent-Bergé relationship was a textbook example of the addict and the enabler.

Still, the brilliant Bergé convinced himself otherwise. “What endures in Yves is his sense of childhood, and his refusal to leave it,” he said. “His work absorbed him and he took refuge in a cocoon—imaginary or otherwise—which he created totally and which he inhabited full time. Yves is [the poets] Hölderlin and Rimbaud. A fire maker.” Had Bergé disappeared, Saint Laurent might have been forced to shape up and change. Yet his business partner did not abandon him, both smitten by his genius and aware that their growing empire depended on looking after Saint Laurent’s talent. Besides, his partner was not the only one behaving badly in Paris.

For an article entitled “70s Paris, The Party Years,” Karl Lagerfeld, at the time Chloé’s ready-to-wear designer, told W magazine that he “hated to be out of town for more than 24 hours … There was the feeling that, wherever you were in Europe, you did whatever you had to do to make it back to Paris for drinks at the Café de Flore, then dinner and dancing at Le Sept.” But apart from the actress and model Marisa Berenson, who lived on orange juice and meditation, and Lagerfeld himself, who never dabbled in drugs or alcohol, fashionable Paris had become as decadent as Manhattan in the Jazz Age or Berlin in the 1930s, with vodka the drink and cocaine the drug of choice. Berenson, the star of the movie Cabaret, recalled “a complete intensity about everything” and how “it was a dangerous time for some … Like anything that doesn’t have boundaries, many people went too far.” Nevertheless, there was an amazing exuberance and euphoria and a sense that something different and brand new was happening in Paris, a sort of unofficial creative movement, featuring fashion talents such as Saint Laurent, Lagerfeld, the designer Kenzo Takada, and the illustrator Antonio Lopez, Loulou de la Falaise, and Vogue photographers like Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin.

According to Marian McEvoy, then working at Woman’s Wear Daily, it was a time “of such extravagance” in Paris. “No one had discreet little cars or passe-partout suits. There was no slinking in wearing a simple black dress—people were there to show off.” “We would just throw together some kind of turban or experiment with something ethnic,” said de la Falaise. “The idea was, ‘what can I invent tonight?’” It was a kind of inventiveness that blurred the distinction between day and night. “Private life, professional life, fashion business, and fashion expression—it all overlapped,” said Lagerfeld. Later, Saint Laurent described all the feverish partying as boosting his creativity. “We went out constantly but we also worked so much,” he told W magazine. “Going out only made us more creative.”

“Even if I am doing a man’s suit, I try to make it feminine.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

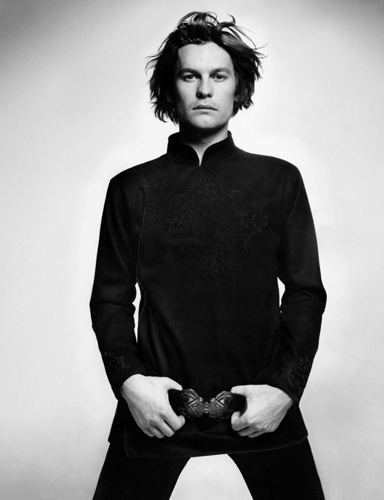

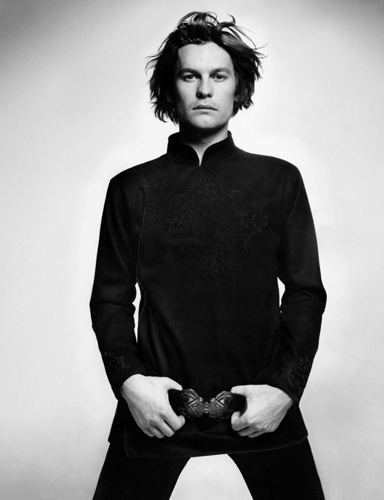

The Austrian actor Helmut Berger was the perfect poster-boy for Saint Laurent’s Rive Gauche Pour Homme; he and the designer were physically similar and equally ambiguously seductive. Here, Berger wears an evening tunic, satin pants, and belt with metal butterfly buckle. Photograph by David Bailey, 1971.

“Are you visibly Saint Laurent?” asked Vogue of these “wicked black chiffons, shrugged off the shoulders” photographed by Guy Bourdin in 1977, styled by Grace Coddington using models Kathy Quirk, Audrey Matson, and Carrie Nygren. Every item was signature Rive Gauche, ranging from the feathered chiffon, gilt, and silk braid accessories to the iconic black satin, gold lace shoes.

“DRESSING IS A WAY OF LIFE.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

A

Vogue’s André Leon Talley recalled a night out on the town with Saint Laurent and Betty Catroux. “Dressed to the nines for a night at Le Sept club, we would start at his apartment on rue de Babylone. First we might sit in his grand salon, with a Goya perched on an artist’s easel surrounded by Picassos mounted on the walls and museum quality Art Deco furniture. Downstairs in the white library, we fueled ourselves with caviar and chilled Stolichnaya like runners before a marathon.” Occasionally, Saint Laurent’s absent-minded behavior needed to be watched. One of his “ubiquitous dangling cigarettes” caused a fire on the white couch that Catroux and Leon Talley quickly doused “with water from the ice bucket.”

During that period, Leon Talley described Saint Laurent as speaking “like a shy schoolchild, startled at being called upon to talk.” “But in top form, and in private, he was wickedly witty and funny: his imitations of competitors were nothing less than mini theatrical productions,” he wrote. When staying at Château Gabriel, the Normandy retreat where Bergé would deposit guests by helicopter, and was decorated by interior designer Jacques Grange, Leon Talley was tickled by how every guest room was named after a character from Proust’s A la Recherche du Temps Perdu. “Most of the time, we would sit in the winter garden, full of exotic hothouse plants and palm trees, watching him spoil Moujik [he gave every dog he ever had the same name, which means “Russian peasant” in French] by slipping him salami from the hors d’oeuvres tray.”

“I belong to a world devoted to elegance.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

“Organize yourself … sepia,” said Vogue recommending the pale and reddish-brown hues of Saint Laurent’s cloche hat, the silk bow around the neck, and fox fur around the collar for the Rive Gauche woman. Photograph by Barry Lategan, 1974.

Seventies superstars: illustrator Antonio Lopez play-acting with model Jerry Hall, styled by Grace Coddington and photographed by Norman Parkinson in 1975. Vogue said that “the scene here is pure Saint Laurent,” and it was. The looks of both Hall and Lopez—ranging from shirts, white cotton pants, and trench coat—were entirely Rive Gauche.

“A MODERN SUIT, A BEAUTIFUL BODY LIKE A PERFECT AIRPLANE.”

JOAN JULIET BUCK

A

At Le Sept, Saint Laurent would sit in a corner, usually next to Catroux and stare; being curious, he was constantly searching out and intrigued by different ideas and moods. After all, Paloma Picasso’s 1940s dress had inspired his most notorious collection in 1971. When talking to Vogue’s Mary Russell in 1972, Saint Laurent admitted that he was “always looking … My eyes never stop.” Regarding his work, he mentioned “a new appreciation for the almost lost art of the artisans, the ones who could not exist without couture,” and cited the importance of his collaboration with the Swiss-based Gustav Zumsteg who ran the legendary Abraham fabrics. “We feel the same currents and trends at the same time—he, way off in Zurich, me here in Paris. Geography has nothing to do with talent,” he said. “Once, when we met after several months’ separation to discuss ideas, I talked about a fabric I saw in my mind—an idea for a dress—and he pulled the fabric right out of his pocket.”

Zumsteg would be on hand for Saint Laurent’s Opéra Les Ballets Russes couture collection in July 1976, which Vogue entitled, “The Romance that shook the World.” To the sound of Verdi and other opera music, his models appeared in a sumptuous mix of velvet vests trimmed with sable, full skirts, and blouses in rich, exotic colors, gold lamé boots, and bejeweled headdresses; bosoms swelled, and waists were corseted. It was an intensely sensual performance, and it resulted in a wildly emotional standing ovation from the audience.

“Classics are something you can wear all your life. I do classic things for women to have the same assurance with their clothes that men have with theirs.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

Camaraderie and style, exemplified by actress-model Anjelica Huston, shoe designer Manolo Blahnik and model Grace Coddington; styled by Coddington and photographed in Sardinia by their friend David Bailey in 1974. Huston is wearing Saint Laurent: Rive Gauche’s bone-buttoned wool cape, pleat skirt, cardigan, muslin blouse, and court shoes.

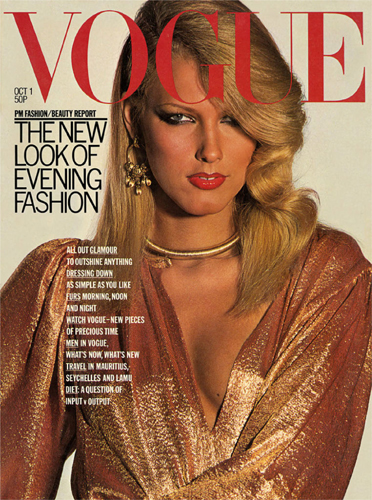

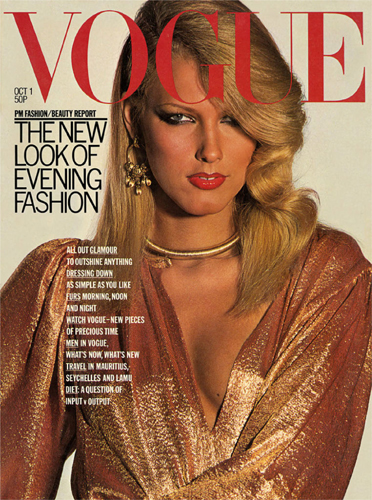

For next two pictures: The curvaceous Swedish model Carrie Nygren gives a sexual charge to Saint Laurent’s designs in an “all-out glamour to outshine anything” shoot for Vogue by Lothar Schmid in 1976. In the first, she wears Rive Gauche’s black mousseline and gold lamé flowered top and black-and-gold lamé skirt; in the second, Rive Gauche’s red lamé blouse, golden braid choker, and bauble earrings.

“Just a ruffle off the shoulders” is how Vogue described Rive Gauche’s Liberty-printed chiffon worn by Marie Helvin and photographed by her husband David Bailey in 1975.

In Vogue, Duane Michals’ four-page fashion shoot illustrated the collection, featuring “glorious heroines” in designs in which “no scale of evening is unaccounted for, the luxe and width of skirt” yet managed to raise “the curtain on a new area of day-into-easy evening dressing.” When questioned by British Vogue’s Leslie White about the collection, Saint Laurent claimed, “Paris was really in the doldrums at the time, people were saying that this city was finished. So I decided to make one of the richest, most extraordinary collections of my career.”

In fact, it was Saint Laurent who was in “the doldrums.” He had suffered a nervous collapse that was treated by the American Hospital in Neuilly as severe depression. His fragile state was the result of Bergé walking out. Packing his suitcase, Bergé had left their rue de Babylone apartment and moved to the Hôtel Lutetia. After giving endless warnings to Saint Laurent about his intolerable behavior, Bergé had made the domestic break, even if he remained permanently in the wings for the designer.

Nevertheless, the suffering caused by Bergé’s departure—his rock had abandoned him—had produced “a violent explosion of fantasy.” It illustrated Saint Laurent’s favorite line from Proust: “In his suffering, he found the ability to create.” Viewing the task as a personal and dreamlike assignment, he decided to include everything that he admired in life, so not only did the collection have the colorful and exotic flamboyance of the Ballets Russes, but also the quiet richness of works of art he loved, like Vermeer’s portrait of Girl with a Pearl Earring. “I have always wanted to do a collection that was a reflection of my taste,” he said. The American retailers reveled in the lushness of fabric and embroidery—American women were going through an exuberant phase; the French purists did not. Although the details were exquisite, some felt it old-fashioned, conservative, and cumbersome. “These are not clothes for women who take the Métro,” the designer confessed. Indeed, in price and tone, they suited the chauffeur-driven superrich.

For next two pictures: The exuberance of Saint Laurent’s Opéra Les Ballets Russes couture collection triumphed particularly in the US, even influencing the high street. Vogue described it as “small-waisted, big skirted,” firing “memory and desire” and defining “high romance.” In the first, embellished chiffon, a turban, and velvet bodice; in the second, Kirat Young models a silk quilted jacket and billowing skirt. Photographs by Duane Michals, 1976.

Six months later, Saint Laurent was back at the American Hospital. In spite of this, in three weeks, he designed the Carmen collection—from his bed. It was highly dramatic, the main theme centering on black velvet corselet bodices teamed with taffeta skirts. It had been influenced by a scandalous production of Carmen, directed by Roland Petit in 1950, starring Zizi Jeanmaire. “I have an enormous tenderness for Roland and Zizi, they really marked my youth artistically,” he told Vogue’s Joan Juliet Buck. In their “News Report,” Vogue exclaimed, “Women loved it and the men went nuts about it.” It was sultry and easy to wear, and its appeal was intensified by a proliferation of jet earrings and chokers. “It was a personal explosion,” Saint Laurent said after the show, which began with the singer Grace Jones, counted 281 outfits and lasted a staggering two and half hours. Backstage, the couturier was described by Women’s Wear Daily as “pale and weak” as well as “brushing tears from his face” as he greeted admirers. He was then rushed back to hospital.

There would be more of the same psychological problems for the next two years, yet Saint Laurent continued to triumph with colorful couture collections like Opium and Broadway which electrified his clients. In the 1977 December issue, Diana Vreeland was quoted by British Vogue as saying: “Yves Saint Laurent has wandered through history with a sort of extraordinary butterfly net and he’s caught some of the most beautiful attributes of women from all ages.” None of the collections were his innovative best but they demonstrated his fertile, imaginative mind. “I don’t try to make a revolution in my clothes each time, I don’t try to be sensational,” he told Vogue’s Polly Devlin. “But I think it’s normal to have something new because life is renewing all the time, and I’m not fixed or static in my thinking or emotions or my designing.”

Owing to Bergé’s business acumen, their company was free of outside ownership in 1972. “I told him it would take ten years for us to become profitable,” Bergé told Vogue’s Gerry Dryansky, “and I was right, to the year.” Following the business plan of Christian Dior, Bergé “began to capitalize in earnest” on the Saint Laurent name. This reached a peak of success in 1974 when Maurice Bidermann, who made and distributed Pierre Cardin menswear in America, stopped working with Cardin and chose Yves Saint Laurent instead and, according to Dryansky, “immediately sold $50 million worth, wholesale, of Saint Laurent blazers and suits that year.” At the end of the 1970s, the Saint Laurent Empire counted over one hundred Rive Gauche ready-to-wear boutiques and a large array of Saint Laurent licensed products bringing in annual net royalties of $18 million.

In May 1977 Loulou de la Falaise married Thadée Klossowski, the painter Balthus’s charming and good-looking son. A few months later, Saint Laurent and Bergé gave them a wedding ball for 500 guests at the Châlet des Iles, set in the swan-filled lagoon of the Bois de Boulogne, which required gondolas to reach it. Demonstrating Saint Laurent’s particular fondness for de la Falaise, he had envisioned and made the entire green-and-white decor, from the awning-striped tent to the enormous columns crossed with satin. Just as they were nearing the end of the decoration, they realized that Saint Laurent had not designed her gown. There was a mild panic in the flou ateliers (dressmaking studios) to create the midnight-blue chiffon dress shot with gold, designed to resemble a summer’s night sky in Marrakech, which had to be kept together by uncomfortable elastic between Loulou’s stick-thin thighs. The morning of the party, she had made the diamanté moon and star headpiece herself, using cardboard, glitter, and glue.

“Things have been wonderful since Loulou came. It is important to have her beside me when I’m working on a collection … I trust her reactions.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

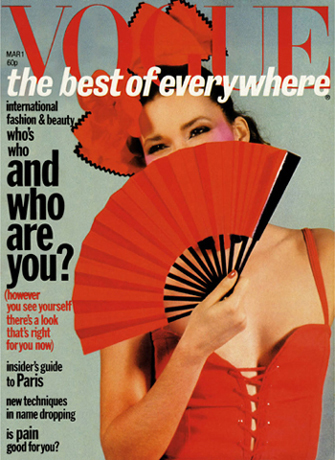

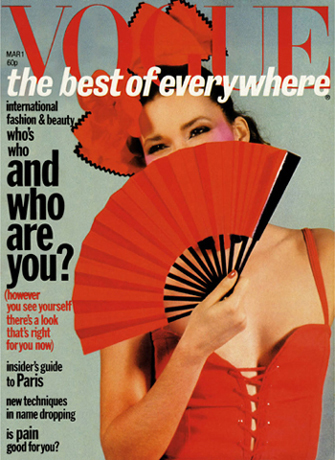

For next two pictures: Saint Laurent’s Carmen collection epitomized a dramatic dressiness, apt for the period, and inspired a Vogue shoot—“The Lady is a Vamp”—and cover, photographed by Willie Christie in 1977. In the first, Marcie James models Rive Gauche’s cotton bodice with bow and poppy in her hair; in the second, Rive Gauche’s flamenco flair includes chiffon blouses, flouncy skirts, silk-fringed shawl, and tassel earclips.

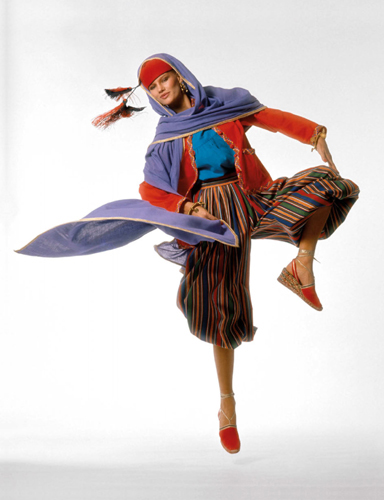

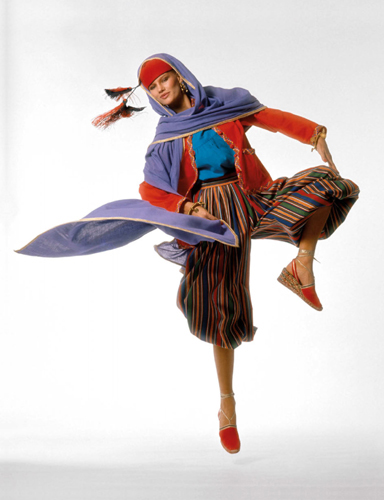

Arja Töyrylä flaunts the Matisselike colors of the Carmen collection. In smock blouse, striped wool harem pants, braided jacket, and fez, Vogue says she is “jumping with joie de vivre as Saint Laurent’s Francoturk.” Photograph by Willie Christie, 1977.

“I CANNOT WORK WITHOUT THE MOVEMENT OF THE HUMAN BODY.

YVES SAINT LAURENT

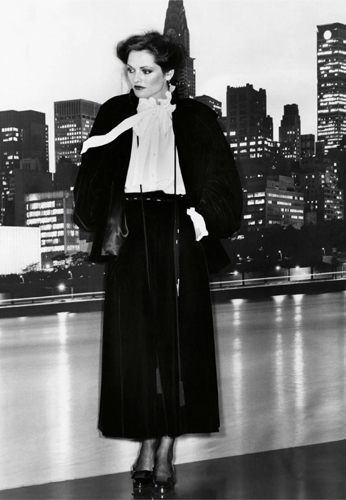

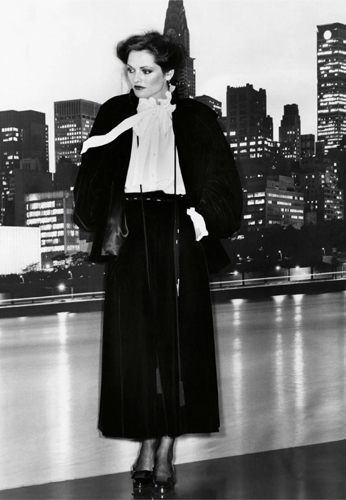

In the dependable chic of Rive Gauche’s classics, Saki Reed Burton illustrates “great black looks with white,” modeling a black velvet dirndl, loose boxy jacket with double ruffle Pierrot collar, and similarly ruffled white silk shirt. Photograph by Eric Boman, 1977.

At this most glamorous of parties, Saint Laurent wearing a dinner jacket, a red cummerbund, and tennis shoes was in gregarious form, chatting and dancing with friends. The next morning, an alarming amount of syringes were found, implying heroin use. In certain circles, the lethal drug had replaced cocaine.

With the opening of Le Palace nightclub in March 1978—Le Sept-owner Fabrice Emaer’s idea of a cooler and less sanitized Studio 54—it was obvious that a darker dissoluteness had crept in. “On one side, it was about going to parties and looking great, but the other side was pretty heavy—doing every drug in sight,” said Marisa Berenson. To inaugurate the much-awaited event—Le Palace would become the nightspot in the late 1970s—Emaer had chosen Grace Jones to perform. She opened with “La Vie en Rose.” Saint Laurent, however, disapproved of Jones’s choice of headdress. Without a word and indicating his accepted authority, he simply went behind her and wrapped the singer’s head in his scarf.

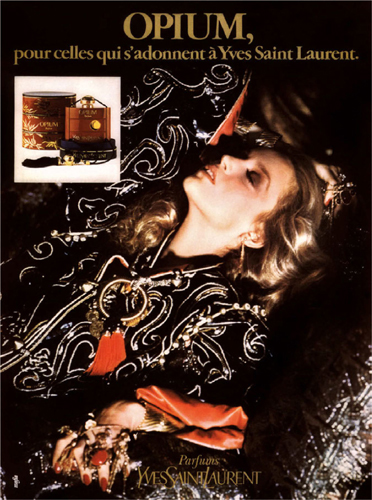

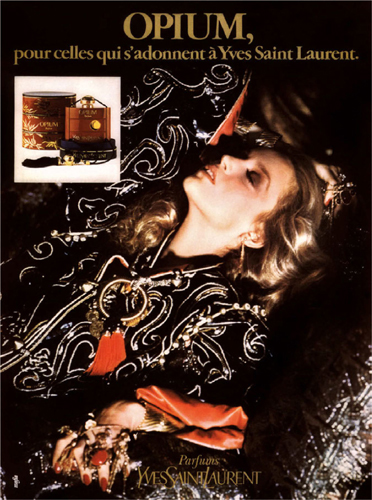

Several months later, there was the New York launch of Opium, Saint Laurent’s bestselling fragrance, whose heady scent defined the era. Helmut Newton photographed the advertising campaign at Saint Laurent’s house in his mirrored Buddha room. Choosing Jerry Hall was an inspired idea. It was at the height of her modeling career and, having posed for endless Vogue covers, she knew exactly how to smolder and provoke. Above her mass of curled blond hair, there was a line that read Opium, pour celles qui s’adonnent à Yves Saint Laurent that, depending on the translation, could either mean “for those who abandon themselves” or “for those who are addicted to Saint Laurent.” The overtones of drug addiction typified Opium’s risqué reputation. When launched in Europe in the fall of 1977, the fragrance had been a hit, particularly at Christmas time. In America, however, Opium’s name caused an outcry with a group of Chinese Americans. They demanded a change of name and public apology from Saint Laurent, insisting that the drug was a holocaustlike reminder of abuse and bloodshed in their country’s history. Oddly enough, the controversy worked in Opium’s favor; it ignited interest and soaring sales.

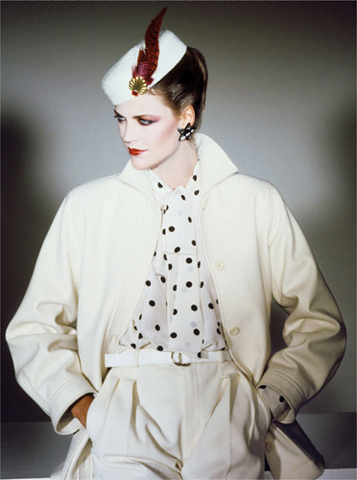

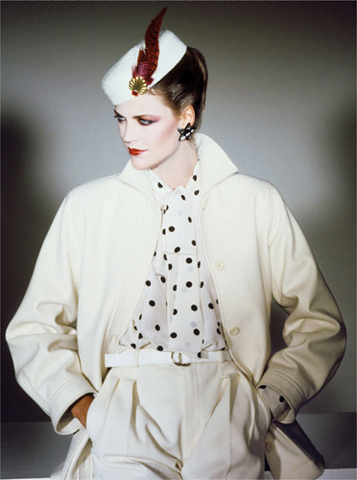

For next two pictures: François Lamy photographed “Paris with a dash of style” for Vogue in 1979: in the first, Mira Tibblin models Rive Gauche’s “heavenly” loose wool pant suit, perked up by polka-dot shirt and lacquered straw pillbox; in the second, Karen Howard wears a sweater, straight skirt, satin scarf, and lacquered straw hat in Rive Gauche’s luscious colors. laboressita dio et.

“I love gold, a magical color, for the reflection of a woman. It is the color of the sun.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

Vogue’s “Final Fling” shoot by Alex Chatelain, 1979 embodied the opulence of Saint Laurent’s couture; model Esmé Marshall gives gamine grace to a brocade matador suit boasting knickerbockers finished with diamanté buttons and satin bows as well as a satin ruffled blouse and organza pleated cummerbund.

Helmut Newton’s 1977 photographs for Opium’s initial advertising campaign, starred Jerry Hall wearing an embellished evening dress from the Opium couture collection.

Squibb, the owners of the YSL perfume division, agreed to spend $250,000 on Opium’s American launch party. Organized by Marina Schiano, the vice-president of YSL in America, the event was held on “The Peking,” a magnificent barque with four masts. Eight hundred invitations had been sent out. Guests were greeted by an extravagant arrangement of 5,000 cattleya orchids, a Proustian reference for Saint Laurent’s benefit, as well as a 1,000-pound (450 kg) bronze Buddha statue that had been hoisted on board. Women’s Wear Daily had written a sour article implying that the soirée was a failure, in spite of the presence of Saint Laurent, de la Falaise, and his top American couture clients. But it is possible that WWD’s owner John Fairchild—fashion’s mischief-maker—had fallen out with Bergé and was causing trouble. This was the first time that a party with an A-list cast had been organized to sell and promote, rather than just celebrate. It marked a changing tide in the beauty world. And it was a tide that was about to hit fashion.

“Yves Saint Laurent invents a reality and adds it to the other, the one he has not made. And he fuses all of this in a paradoxical harmony—often revolutionary, always dazzling.”

MARGUERITE DURAS

A

“A DRESS IS NOT STATIC, IT HAS A RHYTHM.”

YVES SAINT LAURENT

Also from Alex Chatelain’s 1979 “Final Fling” shoot, Esmé Marshall wears a couture evening dress that Vogue described as “Window dressing black velvet around a keyhole of lace,” styled with a nutria fur jacket.