Cause 8

LACK OF PROGRAMMING OR TRAINED TEACHERS

All schools are not created equal when it comes to gifted programming. Local schools are given an immense amount of latitude to work with in regard to what gifted programming, if any, they offer. Unlike with special education students, who are protected under federal law by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 1990), there is no law stating that students must be provided with gifted programming. The question remains, what do we do for underachieving gifted students, and how do we, as an educational system, challenge them? An easy fix would be just to add more services. After all, these are potentially our future doctors, lawyers, politicians, and other such citizens who will be a major factor in steering our society into the future. Would we not want them to have the very best education possible to make these paths easier to traverse?

Yet, very few dollars are devoted to these bright students: For every $100 our federal government spends on education, $3 goes to gifted programming; $91 goes to programs for struggling students. That means if the federal government gave a district $1,000, they would have enough money for gifted to purchase a single $30 textbook. For a classroom set of textbooks for gifted students, the federal government would have to provide $30,000. Very little of a school’s funding comes from the federal government, however. It would probably be more indicative to look at how much the states are spending on gifted programming because this is where a good bulk of school funding comes from. Nearly 40% of districts with elementary gifted programs, 51% of the districts with middle school programs, and 60% of high schools, receive no gifted funding (Callahan, Moon, & Oh, 2014).

Each state decides for itself whether it is going to mandate programming and fund it or not. It looks something like Figure 19. States in green have gifted services that are mandated and fully funded by the state. That is only four states out of 50 that value the education of high-ability students enough to fully pay for it. The purple states mandate gifted programming but are only partially funded by the state. Orange states have gifted services mandated, but the state provides no funds to run the programming. Yellow states do not mandate gifted programming, but state funding is available for those who choose to provide it. The red states mandate no gifted programming and offer no gifted funds.

Although most states have laws that require districts to provide testing for giftedness of their student population, when and how often this testing occurs is left up to the district to determine.

A district might test for giftedness for science in the fifth grade but then never provide the opportunity again. That means the student has a single chance to be identified as gifted in that area. There are other schools that test for giftedness multiple times every year using a test like MAP (Measures of Academic Progress), which gives students multiple chances to be identified in reading and math. It is important to find out the gifted testing policy of your school district and when and how often it tests for giftedness. The district also might have retesting opportunities upon request.

When There’s No Gifted Programming

Because a district has the autonomy to make decisions about how it offers gifted services, there are some districts that do not have any gifted programming whatsoever. This is either because the gifted population is not large enough to warrant a full class of services, budgetary reasons cause the district to focus resources elsewhere, or the district feels it meets the special needs of these students with high expectations in its regular classrooms. Several longitudinal studies have shown the positive effect gifted programs have on students’ post-secondary plans. One study (Lubinski et al., 2001) found that 320 gifted students identified during adolescence, who were involved in gifted programming through the secondary level, pursued doctoral degrees at more than 50 times the base rate expectations. When the researchers checked in with these students at the age of 38, 63% reported holding master’s degrees and above. Of these, 44% held doctoral degrees. Only around 2% of the general population held a doctoral degree, according to the 2010 U.S. Census (Kell, Lubinski, & Benbow, 2013).

Regardless of its importance, if a school is not willing to provide specific programming for its gifted student population, what it cannot take away is good teaching. If you have teachers who are willing to challenge students and provide them with the education needed to grow, then a lack of programming is not the end of the world. You just need to figure out what strategies work with these students.

When There’s No Proper Gifted Programming

Even if a district does have gifted programming, is it effective gifted programming? What constitutes high-quality gifted programming is debatable. Ideally, the best solution is offering a magnet program where students are exposed to a robust and rigorous curriculum, designed to challenge high-ability thinkers, that is provided by teachers who have gone through the gifted certification process. With the additional bussing as well as the teacher training, this could be somewhat expensive for a school system. There are certainly more economical ways to offer gifted programming.

Some choose to cluster gifted students so they are with a few peer-mates who act and think similarly to them. This works if you have a decent-sized gifted population to pull from, but if not, this can be a challenge. Others differentiate in the regular classroom. The idea is to meet the individual student where he is performing. This means if a gifted student is advancing quicker than the rest of the class, the teacher designs lessons to meet these needs. Although this is nice in theory, doing this in a class that has a wide range of abilities can be daunting. Teachers are pulled in other directions by special education students, English language learners, and other groups that might need more time to grasp a concept, pulling them away from the gifted students who need less time. And sometimes differentiation is done in a rigid fashion. Consider reading groups. Do you put the students in the same groups all the time, or do you group them according to how they pretested? Flexible grouping is the key to differentiation, and it takes a lot of work.

Sometimes the service does not match the need. For example, if you have 15 gifted students identified as gifted in math and 32 identified as gifted in reading, yet the program you offer is a math pull-out, you are leaving 32 students without service. It would be better if the program offered reading pull-out to meet the need of a greater number of students. Science and social studies often receive the short end of the stick when it comes to gifted programming. There are not many programs specific to these subject areas, meaning that students who are identified are not going to have their needs met.

Some schools like to claim service through rigorous programs such as Advanced Placement, College Credit Plus, or International Baccalaureate. Although these programs are certainly more challenging in regard to content, they are not specifically designed to meet the unique needs of gifted students. Although instructors might have received specialized training in how to deliver the content of the class, they are not given training in how to challenge gifted students.

When Teachers Do Not Have Skills to Teach Gifted Students

In some cases, teachers working with the gifted population might not have received any training in working with gifted students. We all like to think that good teaching is good teaching, so it should not matter what students a teacher is working with. If she is a good teacher, she will get good results. The reality is that certain types of teachers work well with certain types of students. A teacher who has had a lot of success with special education students might have the innate ability to break things down into smaller parts to make them easier. If you were to put this teacher with a gifted population, the skills might not match up. Gifted students need a teacher who can think quickly on his feet in order to ask higher level questions and encourage critical thinking. This sort of teacher might confuse average students, however, who are not ready to be pushed to think more deeply about a concept or who need more supports before getting to that level.

It is also up to the individual district to decide how it will offer professional development to teachers working with the gifted population. Some districts offer an extensive amount of professional development, exposing teachers to the latest teaching strategies that work well with gifted students. They support teachers going to gifted conferences such as the National Association for Gifted Children’s annual convention, offer waivers for classes at the university that are designed to provide gifted instruction, make available online modules, webinars, or trainings, and have in-house professional development, such as book studies, teacher-based teams, or yearlong discussions. These are all methods that will ensure that the teacher who is providing service to the gifted students is prepared to do so.

Some districts have coordinators who coach teachers to work with gifted students and meet with parents to make sure their child is being challenged. Other districts choose not to offer anything in the way of professional development. There are districts that farm out the gifted coordinator position to someone handling many districts, or an administrator with many other duties, meaning this person has just enough time to make sure the district is following the state mandates for identification and service with no additional time to work with teachers.

It is important to have the right people in place to work with the gifted students along with the proper supports and resources in place. If this is not the case, this mismatch could result in gifted students not having their needs met and thus becoming underachievers.

Practical Solutions

Strategy 1: Learning Centers

A learning center is an independent space set up inside the classroom to provide engaging lessons that enrich student learning. This is why it is an especially effective teaching strategy with gifted students. You can set up your learning centers to extend content already learned, allowing students to go deeper. There are various resources at these centers that allow the students to complete their task. Learning centers also give students the opportunity to have hands-on learning experiences.

Consider a teacher who is covering a unit on landforms. She has set up learning centers all around the room, each one covering a different type of landform. You might have volcanoes, mountains, valleys, islands, and deserts. A student could sit down at the learning center for volcanoes and learn about how volcanoes form, what causes them to erupt, and some of the most famous volcanoes. This could be displayed on a trifold, earmarked in a book, a video on the computer, or an actual model of the volcano. Students would complete the task the learning center has asked of them, learning about the topic in the process.

The great thing about learning centers is you can use them to differentiate as well. You might have three different learning centers covering the topic of volcanoes. One of these centers gives you the very basics of volcanoes, the information every student should know. Another one would go a little deeper, asking students to create rather than just comprehend the knowledge. The third one would pose questions designed to make students think about this basic information at a high level, such as predicting when a volcano is going to erupt or what might have happened had volcanoes not formed in the South Pacific. Students would go to the learning center that indicates their prior knowledge of the topic. If a student knows all the basics, she might want to start at the third learning center. If a student knows nothing, he would want to start at the first one.

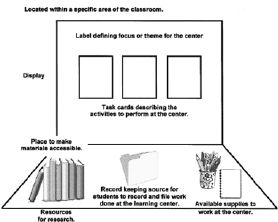

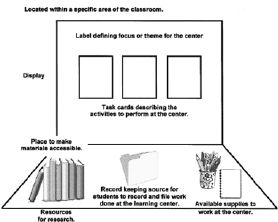

How you set up learning centers is completely up to you, but Figure 20 shows a basic format.

Figure 20. Sample learning center format. Designed for a professional development workshop based on Project Linking Learning (2009–2012), Dr. Sandra K. Kaplan, funded by the Jacob K. Javits Gifted and Talented Student Education Act. Reprinted with permission of Jessica Manzone, University of Southern California.

A learning center is like having an additional teacher in the classroom. It acts as a resource that can enrich the student by reinforcing what has been taught and extending the learning.

There are several choices a teacher can make when it comes to learning centers. They can be used as a rotational system where students work independently, or they can work in small groups. Students can select the learning center they want to be at or the teacher can assign it. The amount of time a student is to spend at a center can vary, as can the implementation. Even with all of these choices, there are a few things that learning centers should include, according to Manzone (2014):

» Location: Learning centers should have a designated spot in the classroom away from the regular lesson so that students can work in a self-directed environment.

» Title: Learning centers should have a label making it very clear what the focus is. It could be something content-specific such as antonyms or more thematic such as revolution.

» Task cards: Each learning center needs to have clear directions written on task cards so that students know exactly what they need to do. Task cards can even be differentiated for different learning levels.

» Time frame: Learning centers need to allow students enough time to accomplish all of the tasks while not becoming repetitive. You should encourage students to develop time management skills as part of their self-directedness, but some guidance is still helpful.

» Resources and supplies: Make sure you provide students with the materials needed to complete their tasks. If you are asking them to be artistic, include art supplies. If you are asking them to research, there should be books or access to the Internet. The students should not have to go outside of the learning center in order to accomplish their tasks.

» Recording system: With so much independent work going on, you need to have a system to track the work students are doing. This can be something as simple as a sign-in log, to portfolios of work, to individual journals.

» Management strategy: Even though the students are self-directed, you need to figure out how best to direct students in the management of the learning centers. How many students can be at the center at a time? How are groups going to be set up? How do students know to rotate to another learning center? Students should be familiar with this so they do not become confused (para. 3–9).

By having these elements in your learning centers, you will be able to produce a well-oiled machine of classroom management where students know what the expectations are. The most important benefit to using learning centers is that they teach many, if not all, of the 21st-century survival skills discussed previously. If your school does not have gifted programming, learning centers are a good way to challenge gifted students in the regular classroom as well as differentiate for high-ability thinkers.

Strategy 2: Blended Learning

Blended learning is one of those buzzwords popular amongst educational innovators. With the increase in technology in the world, increasing the amount of technology we use in the classroom makes perfect sense. But what does blended learning look like? Do we put a computer into the hands of a student and expect it to teach them? Like any other teaching resource, you need to find a way to use technology as enrichment for a particular lesson. If you can teach the lesson better without the technology, you should not be using it. Technology for technology’s sake is a poor model for use in the classroom.

How does one use blended learning in a classroom with gifted students? There are six models to consider when using blended learning (Thompson, 2016):

» Face-to-face: For a diverse classroom with high-ability and below-average students, this model allows gifted students to move forward at a more rapid pace. The teacher drives students’ progress, in some cases giving them the websites to go to, and monitors their progress. It does allow for differentiation but is not as self-directed as other models.

» Rotation: Students rotate through stations, each of which includes technology. There is a combination of face-to-face time with the teacher and online work. Students can be divided into groups based on skill level. Those struggling will get more face-to-face time.

» Flex: The teacher acts as a facilitator, but most instruction is online. Although this can be used with gifted students to allow them to work at their own pace, the online content usually is not very in-depth.

» Online lab: The instruction is completely online. There are not certified teachers present but paraprofessionals who supervise. Many community and credit recovery schools use this model. It is not ideal for gifted learners, but works for those who may need flexibility with their schedule because of other responsibilities. It does allow gifted students to progress faster than a traditional school setting but does not necessarily provide the amount of depth to challenge them.

» Self-blend: Traditional class time provides the basic instruction, and online content is used to supplement. This model is useful if a student exhausts all of the traditional classes a school has to offer and wants additional learning. Students can use this method to take college courses for credit without having to leave the school. This works fairly well with gifted students because it allows them to be independent learners. It also works well with underachieving gifted students who are turned off by traditional schooling and need an alternative to motivate them.

» Online driver: There is little to no interaction face-to-face with the teacher. Students work from home, and any questions are communicated electronically with the instructor. This can work with gifted students who are highly motivated and want to move much faster than a traditional school setting allows.

Matching the correct model with the needs of students is important. If a student has been in the system long enough and has turned his back on traditional education, nontraditional methods such as online school lab and online driver might be more appropriate. If the underachieving gifted student is just at the beginning of her disillusionment, having interactive models such as the face-to-face and station rotation to reengage her in school would be beneficial.

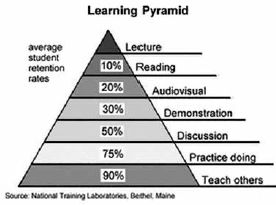

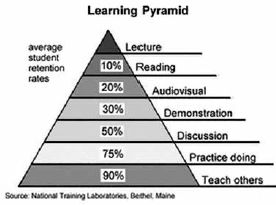

Strategy 3: Students as Teacher

The National Training Laboratories (NTL) in Bethel, ME, conducted a study to determine what type of learning caused students to retain information best. The NTL looked at different intelligences such as listening and seeing, as well as different methods of learning. What they found was that the most effective learning, where students retain 90% or more of what they learn, is to teach others. Now this is different than putting a gifted child with someone who is having difficulty and expecting him or her to tutor the child to success. This is about gifted students sharing what they have learned on their terms and being able to communicate this clearly to others. And yet, we rarely use this learning style in the classroom. A traditional classroom will probably have activities such as lecture, reading, and audiovisual components, which when added together only give a 60% retention rate (see Figure 21).

Figure 21. Learning pyramid. From “Learning Pyramid” by National Training Laboratories, n.d., retrieved from http://www.ntl.org. Copyright by National Training Laboratories. Reprinted with permission.

As teachers, we have to become experts on the content before we can teach it to others. We also have to present it in such a way that those who are not experts can understand. By having students teach the class, they are going to have to become experts. Not only that, gifted students have a vast array of knowledge and skills that their age-mates may not possess. Giving them a venue to share this will improve not only their retention of that information, but also their public speaking as well as organizational skills.

This might look like an inquiry project. You start with a key topic: for example, space. From that, students generate a list of keywords concerning the topic, such as universes, planets, comets, moons, NASA, solar system, sun, exoplanets, stars, etc. Based on their interests, students are flexibly grouped. There might be some groups with five people; there might be a single person interested in a topic. The point is that they get a choice in what they are going to be teaching.

Students then become experts on the topic, building on knowledge they already possess. They can research, interview experts, read books, and watch videos, to learn the material well enough in order to teach it. Throughout this process, they will write learning objectives that they plan on teaching others. Students should have three to five learning objectives. They might look like this for black holes:

1. What causes black holes to form?

2. What do black holes do?

3. What are some black holes that have been discovered?

Then, you push students to create a learning objective with no clear answer—one where they will have to take what they learned and hypothesize, such as: What would happen if a black hole formed in our solar system?

Students then set out to find a way to teach these learning objectives in whatever creative way they can come up with. They could create learning centers, give a presentation, or facilitate a hands-on learning activity. Students would then have performance days to teach their lessons. It is best to provide an estimation of the time allotted for each presentation, so that students know to include enough material to teach the concepts but don’t include so much detail that they take too long.

These do not need to be inquiry projects. You could take a few chapters from the textbook and divide students into groups, each one covering a chapter and teaching it to the rest of the class. By having them teach the class, you are helping students learn the content at a deeper level and develop an enduring understanding.

Conclusion

Learning centers, blended learning, and students as teachers are all strategies that can be used in the regular classroom to engage gifted students. Because there is choice, students have some say in their schoolwork and can use their gifts in creative ways. These are good alternatives to a lack of programming or trained teachers but are by no means a replacement. This is no substitute for proper gifted programming and highly trained gifted intervention specialists in challenging and engaging gifted students.

If you would like to read more in-depth about one of these strategies, a good resource is Differentiating Instruction With Centers in the Gifted Classroom by Julia L. Roberts and Julia Roberts Boggess.