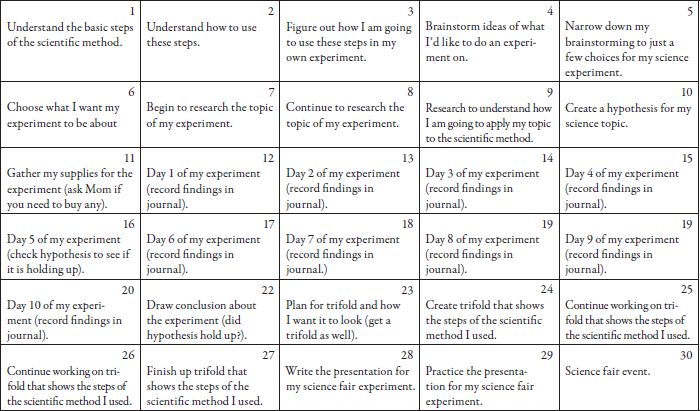

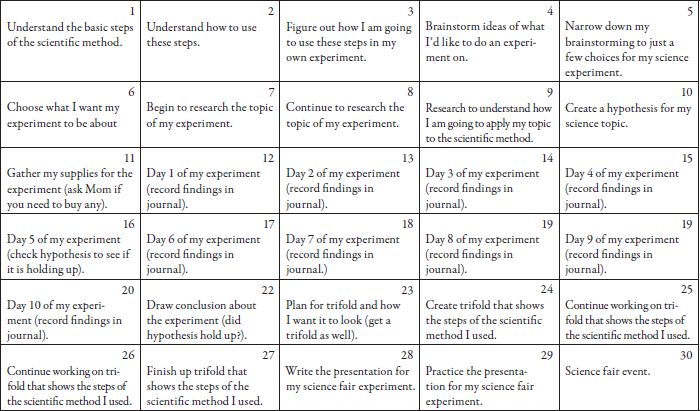

TABLE 10

Sample Calendar

Cause 10

BEING TOO SMART FOR THEIR OWN GOOD

Is there such a thing as being too gifted? When one looks at a highly gifted individual like Bobby Fischer, it causes one to wonder. Bobby Fischer was a chess prodigy, who, at 14, became the U.S. Chess Champion and then the only American World Chess Champion at age 29. Some of the quirks that made him unique, however, also caused him to ostracize himself from the game. He refused to defend his World Championship when the governing body would not relent to his sometimes ridiculous requests. He eventually became a recluse, living in Iceland, spiraling further and further into erratic behavior.

As a child, Ted Kaczynski had an IQ of 167 and was accepted to Harvard at the age of 16. He got his doctorate in mathematics but, at age 29, moved to a remote cabin in Montana without running water or electricity. He then spent the next 18 years mailing homemade bombs to individuals under the guise of the Unabomber.

Clearly, these are two extreme examples of highly gifted individuals gone wrong. Not every super genius is going to end up descending into madness, but there are certainly challenges to being much smarter than the general population (Lebowitz, 2016):

» You often think instead of feel.

» People frequently expect you to be a top performer.

» You might not learn the value of hard work.

» People might get annoyed that you keep correcting them in casual conversation.

» You understand how much you don’t know.

» You tend to overthink things.

Many of these have been discussed previously, but the one that trips up many gifted students is overthinking. Their brains run at such a rapid pace they do not see Occam’s razor, a problem-solving strategy that suggests the simplest solution is oftentimes the best. On a multiple-choice test, a student with advanced thought processes might attempt to rationalize how any of the choices could be correct. Or a highly gifted child working in a group of students might want to discuss and debate the merits of the group’s choices while everyone else thinks they have a solution and want to move on. Sometimes a gifted student can be his own worst enemy.

When Perfectionism Strikes

Perfectionism is more common in gifted students than in typical students. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Having high expectations and wanting what you are working on to be your best work can lead to some positive results (NAGC, n.d.a):

» doing the best you can with the time and tools you have,

» setting high personal standards with a gentle acceptance of self, and

» not allowing behaviors to interfere with daily life (Sec. 1).

The issue is not that the child wants to be perfect. Issues arise when she allows the perfectionism to cause her to freeze her ability to do anything until she believes it to be perfect. Examples of unhealthy perfectionism are (NAGC, n.d.a):

» emphasizing and/or rewarding performance over other aspects of life;

» perceiving that one’s work is never good enough;

» feeling continually dissatisfied about one’s work;

» feeling guilty if not engaged in meaningful work at all times; and

» having a compulsive drive to achieve, where personal value is based on what is produced or accomplished (Sec. 2).

When perfectionism gets in the way of productive achievement and generally being happy, it becomes a social-emotional issue that can affect academics. A student might stare at a test, terrified to put anything down for fear of making a mistake. As a result, she does not finish the test. Or, a student gets feedback from the teacher, but he cannot take the criticism and use it constructively. Instead, he sees it as a condemnation of his work and himself.

Sometimes perfectionism can be a combination of a student wanting to be perfect and the high expectations of parents. If a parent accepts nothing lower than an A, there is not much room for error, so the student thinks he needs to be perfect. There are things the teacher and parents can do to help students cope with perfectionism (NAGC, n.d.a):

» model a healthy approach and be aware of the student’s predispositions toward compulsive excellence;

» refrain from setting high, non-negotiable standards;

» emphasize effort and process, not results;

» do not withhold support or encouragement if goals are not met; and

» focus on positive self-talk (Sec. 3).

Recognizing a student has the tendency to be a perfectionist is half the battle because then you can offer the help and support the student needs when you see the symptoms arise.

When Other Issues With Too-Smart Children Arise

People will often joke that they suffer from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) because of a little quirk they have, such as wanting to be sure their hands are constantly clean or feeling compelled to take that one pencil that is pointing downward and turning it so it matches the others. OCD, however, is a very serious condition that can cause one to become impaired or distressed. It is not as simple as a quirk. It is a repetitive behavior that the person feels compelled to do. Sometimes it can be seen by others, such as flipping a light switch up and down 37 times each time you leave a room, but other OCD can be internal, such as repeating a phrase over and over again in your mind. Here are some characteristics and examples of behavior of students who are gifted and have OCD (Caccamise, 2013):

» Fear of contamination: The student is always cleaning up and/or washing and rewashing her hands; she might have dry, chapped, cracked, or bleeding hands that may resemble eczema.

» Fear of harm, illness, or death, or pathological doubting: The student is always checking things; he has a compelling urge to return home to check on something or is constantly checking his locker and/or backpack.

» Symmetry: The student is often arranging; she might tie her shoelaces until both look identical, duplicate steps from one place to another, and/or arrange books on a shelf until they appear symmetrical.

» Number: The student counts, repeatedly counting up to a particular “magic” number.

» Scrupulosity (fear of doing or having done something evil): The student seeks penance, repetitively saying mental prayers or mantras (p. 2).

OCD can interfere with a student’s ability to perform where he is capable. There are strategies a teacher can take to help students cope with OCD (Caccamise, 2013):

» Teach students about learning strategies (i.e., breaking work up into chunks, using a laptop for writing).

» Help students identify strategies that work for them (i.e., seating arrangements, allowing them a permanent bathroom pass).

» Help students set short-term goals.

» Set small steps to accomplish a task (i.e., taking a test, writing a story, completing math assignments).

» Emphasize students’ strengths and help them work on their weaknesses.

» Look for triggers.

» Develop cues with students that will help them refocus (you might even have a safe place for them to go).

» Be flexible with deadlines (p. 2).

Again, it takes the eye of a knowledgeable teacher to recognize when a student might be struggling with their impulses and defusing the situation. The teacher should not be disciplining the student for having these behaviors; rather he should be figuring out a way to work with her so that she can use her gifts.

When Abstract Thinkers Cannot Develop Concrete Answers

The gifted mind can be very adept at thinking in an abstract manner, which means gifted students are often able to reflect on ideas. You might hear them say, “I wonder . . .” or, “What if this happened . . . ?” They are able to think about situations that are not present, but other students may only be able to think about what is right in front of them. Abstract thinkers:

» are able to use metaphors and analogies with ease;

» can understand the relationship between both verbal and nonverbal ideas;

» possess complex reasoning skills, such as critical thinking and problem solving;

» can mentally maneuver objects without having to physically do it, known as spatial reasoning;

» are adept at imagining situations that have happened or are not actually happening; and

» appreciate sarcasm.

Abstract thinking is great when you are having discussions, working on design challenges, or sharing new ideas, but it does not always translate well to traditional assessment. Many assessments require concrete thinking, and these types of students can sometimes find it difficult to make the translation from abstract to concrete. As a result, they struggle in a traditional classroom with its emphasis on the concrete. There are other classroom environments that are much more nurturing, where there are open-ended questions, encouragement of creative solutions, and instances where students can give their opinion rather than just an answer. If abstract thinkers are not blessed with a classroom such as this, school can be a struggle and underachievement begins to settle in.

When Students Only Know How to Play the Game of School

As discussed, some gifted underachieving students are not willing to play the game of school (see p. 108). On the other hand are students who know how to play the game of school so well that they get out of ways to challenge themselves. These are students who know exactly what they have to do in order to get a good grade in a class but are not willing to go above and beyond that. This student will do her homework, turn in assignments, and, for all those observing, seem compliant. This student, however, is not giving it her all. She is an efficiency expert, doing the bare minimum in order to succeed. She is not willing to challenge herself, and, if the teacher runs a classroom where there is no challenge, this student is perfectly fine with this.

For these types of students, it is hard to argue with their logic. Why work hard and take chances when you could be getting the same grade, or even a better one, by doing exactly what is asked of you and playing it safe? These students are smart enough to do what is necessary to get a good grade, but they lack accuracy in their work. Accuracy involves:

» craftsmanship of work, or quality;

» communicating the answer clearly;

» learning for learning’s sake, not just getting it done;

» persistence for fidelity;

» taking pride in your work; and

» setting high standards.

Ideally, you want all students to strive for accuracy, but especially gifted students, because otherwise they are not going to grow as learners. If they set the minimum standard or concern themselves with just completing a task, they are not going to be tapping into their potential. In order to grow as learners, students have to do more than just allow the teacher to challenge them; they must figure out ways to challenge themselves.

Practical Solutions

Strategy 1: Activities That Translate Abstract to Concrete

Translating the abstract to the concrete can be difficult for some gifted students. Consider the saying, “See the forest for the trees.” If someone can see the forest for the trees, he can see the big picture. This same person, however, might not be able to describe a single tree in detail. Abstract thinking is about the big picture, but concrete is much more specific. Take, for example, love, an abstract concept. It means very different things to very different people. And one’s definition of love evolves over time. When you are a child, you love your parents and your toys. When you get older, you love your spouse or your children. There are, however, very concrete examples of love:

» an elderly couple celebrating their 50th anniversary,

» a baby snuggling with her stuffed teddy bear,

» a couple exchanging their wedding vows,

» a man in his 40s waxing and caring for his sports car, or

» a woman finding the perfect pair of shoes for a reasonable price.

In order to get students to go from the grandiose ideas that are swirling about in their heads to something they can put on a page, you have to engage them in lessons that allow them to access abstract thinking. One way to take thinking from abstract to concrete is to interpret paintings. Take, for example, Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night. Have students create a story based on the painting. Some students might choose to focus on the little town off in the distance, some might make the mountain in the foreground the setting, or those science fiction fantasy fans might have the story taking place within the night sky. Regardless of where they set the story, students must visualize something specific, starting to think in a concrete manner.

The same can be done interpreting poetry, which is usually very abstract. Have the students find the concrete. Consider “This Is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams. Although the imagery is very concrete, there is some abstractness. Who is the poem for? The title suggests that the author is telling it to someone. Who is the author talking to? What is his relationship with the person he addresses in the poem?

You can also take the abstract to the concrete in math. Math has a lot of abstract concepts. Just the act of learning to count has many abstract qualities to it. Students must take these abstract mathematical concepts and create concrete answers. One way to do this is through the use of manipulatives, items you can touch and move around that allow a student to count, figure out fractions, discern patterns, and complete other math tasks. These include blocks, shapes, base 10 blocks, Unifix cubes, fraction bars, and plastic counting cubes. They can also be everyday objects used to aid in the learning of math. Using manipulatives in the math classroom with underachieving gifted students can help them bridge the gap from abstract to concrete thinking.

Strategy 2: Goal Setting

Setting goals allows students to see the finish line not as some far-off aspiration that seems too difficult to accomplish, but rather as short tasks. If you were told you had to run a marathon, that would seem like a daunting task, but if it was broken up into 26 one-mile increments, it seems more achievable.

It can be as simple as breaking a long book into sections to read:

The Grapes of Wrath—Due date March 13

Week 1: Read pages 1–115.

Week 2: Read pages 115–230.

Week 3: Read pages 231–345.

Week 4: Read pages 346–464.

The goal is to have read a certain amount of pages so the student does not have to read the entire book in a few days because she procrastinated. The goal can be more complex and involve breaking a long-term project into shorter goals:

History Research Paper—Due September 24

Week 1: Conduct research on the railroad.

Week 2: Write rough draft of paper.

Week 3: Continue writing the rough draft.

Week 4: Type the final draft.

In both of these cases, the goal is completion. You can also have students set quality goals. It is not as simple as, “Get an A on a test.” There needs to be an action plan as to how that is going to happen. You have to set incremental goals called benchmarks:

Day 1: Review notes with a highlighter.

Day 2: Rewrite important concepts from notes.

Day 3: Create index cards with important terms.

Day 4: Have Mom quiz me over index cards.

Each goal builds on the one before and involves a specific action that leads to the final goal. It is a blueprint for how to achieve the goal that if a student followed, she would be most likely be successful.

Depending on how much guidance a student needs, you can use a daily goal sheet to ensure that the student is on track. A weekly goal sheet might look like Figure 25.

Figure 25. Sample weekly goal sheet.

Week 1

Day 1

Goal by the end of the day: __________________________________

How I plan to achieve this goal: ______________________________

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

Verification that I achieved this goal (teacher/parent/peer signature):

__________________________________________________________

Day 2

Goal by the end of the day: __________________________________

How I plan to achieve this goal: ______________________________

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

Verification that I achieved this goal (teacher/parent/peer signature):

__________________________________________________________

Day 3

Goal by the end of the day: ___________________________________

How I plan to achieve this goal: _______________________________

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

Verification that I achieved this goal (teacher/parent/peer signature):

__________________________________________________________

Day 4

Goal by the end of the day: ___________________________________

How I plan to achieve this goal: _______________________________

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

Verification that I achieved this goal (teacher/parent/peer signature):

__________________________________________________________

Day 5

Goal by the end of the day: ___________________________________

How I plan to achieve this goal: ______________________________

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

Verification that I achieved this goal (teacher/parent/peer signature):

__________________________________________________________

Strategy 3: Time Management Skills

Time management is a 21st-century survival skill every student could benefit from. It is especially effective with gifted students who are underachieving due to overthinking. Some students either wait until the last minute to complete a project, because in the past they were able to get away with it, or they think they have little to no chance to pull it off in the time allotted. Being able to manage time allows students to take very big ideas and chunk them into smaller parts, making them more manageable.

One strategy is backward building. A student starts the project by envisioning what the ideal final product will look like. Backward building uses a model established by Wiggins and McTighe (2005): First, students identify what will be accomplished, then they determine what product will best show what they have learned, and finally they plan how they will develop and execute the product.

For example, a student has been assigned a project where she has to prepare an experiment for the science fair. She has been given 4 weeks to accomplish the task, and the end product is a trifold display that she presents. Looking at the big picture, this may seem like a daunting task, but by backward building and breaking it into smaller chunks, it becomes very manageable. The student envisions what the project will look like at the end: Present project to visitors at the Science Fair. Working backward, the student determines what she must complete in the step before the last. She will probably want to practice her presentation so it sounds rehearsed and professional: Practice Science Fair presentation. Before she can practice, however, she will need to have created her display that describes her work: Create trifold display with steps and results of the experiment. The student continues until she has created a series of steps that will lead her to the final product:

» Present project to visitors at the Science Fair.

» Practice Science Fair presentation.

» Create trifold with steps and results of the experiment.

» Draw a conclusion about your experiment (Did it meet the hypothesis?).

» Conduct experiment.

» Gather supplies for the experiment.

» Create a hypothesis of what the outcome will be.

» Research the experiment to understand the science behind it.

» Decide on what the experiment is about.

» Brainstorm possible ideas for the science experiment.

» Understand what the scientific method is and how to use it.

Now that this student has broken this large project into smaller tasks, the next step is estimating how long each of these steps will take. For example, conducting the experiment may take 10 days, while creating the trifold might only take 3, whereas gathering supplies might only take 2 days. Remind your student this is only an estimate. She might only take 2 days to research the science behind the experiment but may find she needs more time to get her trifold ready. The schedule is not written in stone, but it does provide checkpoints for the student to notice if she is behind schedule. If she finds herself an entire week behind, she is not managing her time well, and she will need to adjust accordingly in order to catch up.

To aid with time management, a calendar might be a good resource (see Table 10). Without these periodic deadlines, students may wait until the last moment to try to do everything. Whenever the teacher sits down to conference with a student, it is helpful to look at the calendar to chart the progress. A calendar allows students to break the project into parts, making it more doable, and helps them to see the steps necessary to complete the project.

TABLE 10

Sample Calendar

Conclusion

Because a very intelligent child’s brain is running a mile a minute, it is important to develop strategies that focuses it and slows it down. This can aid a child who suffers from OCD, perfectionism, or has difficulty translating the abstract into the concrete, and who might otherwise descend into underachievement.