Eastern Gateway and Strategic Citadel

UPON MY FIRST RRIVAL IN XIAN IN THE SPRING OF 1983, BESIDES THE remnants of its Ming Dynasty (1368–1643) wall, the place looked no different from any other Chinese city. It had endless rows of low-rise apartment buildings interrupted only by large and already decaying Soviet-style buildings. However, upon making my way to the area north of the city’s Drum Tower, which is a warren of narrow streets and alleys filled with small shops, I discovered a magnificent looking structure created exquisitely in traditional Chinese style; it was the city’s grand mosque, originally built in 742 CE. Unlike other monasteries and temples that the government had reconstructed in the 1980s to earn tourist dollars and demonstrate Communist religious tolerance, the mosque was a functioning place of worship that devout Chinese Muslims zealously guarded and maintained. This building, with its venerable age and once-foreign religion, brought home that Xian had been the storied Silk Road’s eastern terminus. The Silk Road was a series of caravan routes that traversed the steppes and deserts of Eurasia and linked together East Asia, South Asia, and West Asia. Its eastern terminus attracted foreigners from across Eurasia who brought not only their splendid goods but also exotic religions.

Although Xian was the capital of China’s earliest and most powerful imperial dynasties, visible traces of these regimes are few because Chinese built their palaces and temples with wood rather than stone. In 1992 I set out to find some of their traces by visiting the ruins of Weiyang Palace, which was the Western Han Dynasty’s (221 BCE–8 CE) governmental nerve center. At the stop for a bus that would take me there, I asked a waiting farmer how far the ruins were from our location. He told me that they were very far; moreover, they were not worth visiting anyway: “It is just a big pile of dirt,” he said. Undeterred, I piled into an extremely crowded bus. We went only one stop when the same farmer yelled to me that I should get off. Upon exiting the bus, I realized that the farmer had been speaking the truth: before me was a huge pile of dirt. But what a magnificent pile it was!

All that remains of the palace is its anterior hall’s foundation. Emerging three or four meters from the ground, it is quite large and leaves one with the impression that Weiyang Palace was a magnificent wooden building that soared loftily above all others. From the topmost building the view of the city must have been stunning indeed. Ordinary people looking at the elevated palace from afar must have believed that they were staring at a heavenly abode. Except for a couple necking in the back of a black “Red Flag” sedan that was parked on the anterior hall’s lower foundation, all of this was easy to imagine because the place was entirely deserted. The ruins showed me that, with only a little bit of imagination, envisioning the grandeur of China’s imperial governments was easy.

Much as in the past, Xian continues to serve as a crossroad that draws people from all over, whether they be Uighur peddlers from Xinjiang, Chinese software entrepreneurs from the coastal provinces, or tourists from Europe, Japan, and North America. Consequently, as in the past, it functions as China’s most cosmopolitan interior city. Of course, what brings people now are not exotic goods coming from faraway lands but rather archaeological treasures from the city’s storied past. It is this combination of ancient splendors and the modern assimilation of diverse influences that keeps me returning to this ever-changing city.

This chapter will discuss the place of Xian in China’s early history. For the first two thousand years of China’s history, from the beginning of the Western Zhou Dynasty in 1049 BCE until the end of the glorious Tang Dynasty in 907 CE, no city in China was more important. We will first explore the geographical reasons for the strategic importance of the Xian area. Then we will survey its history as the seat of China’s early imperial dynasties: the Western Zhou (1049–771 BCE), the Qin (221–207 BCE), the Western Han (206 BCE–8 CE), the Sui (581–617 CE), and the Tang (618–907). In our discussion of these dynasties I will underscore how interactions with foreigners constantly shaped early Chinese polities and how the Silk Road made an indelible impression on the material culture, vernacular customs, and spiritual values of the Chinese living in medieval Xian.

XIAN AND THE WORLD:

A Strategic Location for Commerce and Empire

Xian’s importance in history has everything to do with its geographical location. Mountain ranges enclose all sides of the lower Wei River basin in which Xian is located. The tallest of these mountains are in the Qinling Range to the city’s south; its highest peak soars to 12,389 feet. The range’s height is so forbidding that it prevents humid air from the south from entering northern China, thus separating the moist south from the dry north. East of Xian lies the Xiao Range, which affords access to Xian only via the easily defended Hangu Pass, sitting at the confluence of the Wei and Yellow Rivers. Due to its mountain barriers, Xian is easy to defend, and the area was traditionally called Guanzhong “[The Land] Within the Passes” or Guannei “[The Land] Inside the Gates.”

Guanzhong’s soil is very fertile, but northern China’s sparse rainfall does not guarantee dependable agriculture. The lower Wei River Valley, however, is blessed with eight rivers that farmers rely on to grow their harvests. Thus, due to its protective mountains, abundant water, and rich soil, the Wei River Valley was an ideal place in which to live, which is why people flocked to this area and it became one of China’s oldest urban settlements. In fact, its semi-arid climate, lack of forest cover, and numerous waterways made it comparable to other early centers of civilization, such as Babylon in Mesopotamia and Harappa in the Indus River Valley.

Xian in the Western Zhou (1049–771 BCE)

Xian first became the site of a capital during the second, historically verified dynasty, the Western Zhou (1049–771 BCE). In the twelfth century BCE the Zhou people resided in what is today western Shaanxi province. From both the historical and archaeological record we know much about the Western Zhou, which controlled both the Yellow and Huai River Valleys. It shared many characteristics with the people of the first historical dynasty, the Shang. Like the Shang, noble Zhou families believed that their strength came from their powerful ancestors. They envisioned these ancestors as spirits who were interested in their descendants’ success and had needs of their own. No activity, then, was more important than offering them sacrifices in either gratitude or supplication. These sacrifices occurred at the ancestral temple and were offered in the most precious wares the Zhou people owned: bronze ritual vessels. To ascertain the ancestors’ wishes, nobles of both the Shang and Western Zhou made use of scapulimancy (i.e., they applied fire to the cracks of tortoise plastrons, the abdominal surface of the shell) and cow scapula to communicate with the spirit world. In some cases Shang and Western Zhou scribes wrote on the bone the questions that were put to the ancestors and the ancestors’ answers. In Western literature these divination records are known as “Oracle Bones”: they furnish the first evidence of writing in China.

Like the Shang, Western Zhou warriors held two-horse chariots in high esteem. These vehicles came to China from contact with central Eurasian pastoralists, who were the first to harness the horse for both transportation and war. From atop the mobile platform of the chariot, an archer could easily shoot his enemies while a second warrior with his halberd stabbed or hacked approaching foes. These military vehicles were so effective that in ancient China a state’s strength was commonly measured in the number of chariots it could muster. They were expensive to build and maintain, and the warriors in the chariots were nobles who engaged in much training to master deftly using a weapon while riding the chariot. These vehicles’ overriding importance is evident in many Western Zhou nobles’ tombs, which bore a separate chariot pit. Within the pit is an actual chariot along with its two horses and the unlucky driver. The Western Zhou noble spent so much time in his chariot that he needed it even in death.

Although we do not know to what extent the Western Zhou engaged in commerce with their neighbors, it is clear that the Zhou had extensive dealings with northerners, who they called the Rong and Di peoples. These were bronze-making cultures that lived in permanent settlements and depended on both agriculture and stock breeding. They resided in the modern-day provinces of Xinjiang, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang, Liaoning, and Jilin. Western Zhou grave goods reveal heavy Rong and Di influences: bronzes inspired by movable goods used by pastoralists, body ornaments with animal motifs, and a marked increase in horse and chariot paraphernalia. Steppe goods and art no doubt entered Western Zhou material culture sometimes through trade, sometimes through war.

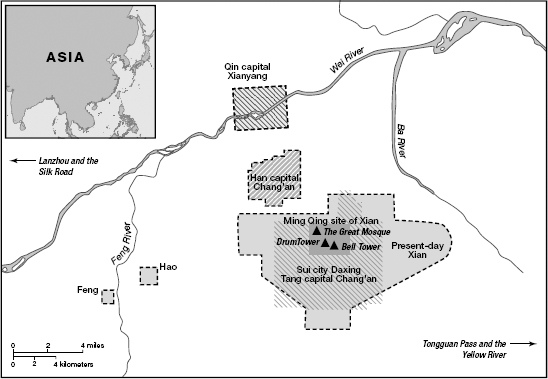

Xian in the Wei River valley was the capital for many of China’s earliest and most powerful dynasties. This map shows the sites of the Western Zhou capitals of Feng and Hao, the Qin capital of Xianyang, Han dynasty Chang’an, and the Sui capital of Daxing, which the succeeding Tang dynasty renamed as Chang’an. By Ming and Qing times (1368–1911), the city was only a provincial capital and a mere shadow of its former self. Take note of its small size compared to the Sui/Tang city.

By the early eighth century the Western Zhou was teetering. Non-Chinese people who were probably being pushed out of the steppe by more aggressive groups menaced the Wei River Valley. Finally, in 771, the Rong successfully invaded the capital and killed the last Western Zhou ruler, King Yu. The Zhou nobles fled eastward to Luoyang in modern-day Henan Province and established the Eastern Zhou (770–256 BCE). This forced move highlighted the Zhou government’s weakness, and as a result, local lords felt emboldened to run their fiefs as autonomous states. Although the Zhou continued to exist nominally, it controlled only the capital area; the rest of Eastern Zhou China consisted of over a hundred autonomous but unstable states. Internally, threats came from hereditary nobles who had their own land and troops and frequently overthrew their rulers; externally, other Chinese states often endeavored to conquer their weaker neighbors. To protect themselves rulers distanced themselves from the old warrior nobility. They turned to infantry armies composed of commoners to fight their wars and bureaucrats to centralize their governments. The men they recruited as officials were not the powerful warrior aristocrats but rather lesser nobles known as shi, “knights or lower officers,” and commoners who had neither independent status nor power. Due to this process, by the end of the Eastern Zhou the shi emerge as the ruling class made up of scholars and officials.

One of these shi was Confucius (551–479 BCE), who despised his era’s chaos. Confucius wanted to return China to the idyllic conditions that supposedly prevailed under the first Zhou rulers who took self-perfection and the people’s welfare to be of paramount importance. Self-cultivation was central to his message: a good man is one who is always striving to improve himself morally. Confucius believed that one did so by guiding his conduct through following the Li, the Zhou kings’ rules of conduct and rituals. If a ruler could act like these ideal, ancient kings, then people from other states would flock to him. Although his disciples were prized for their extensive knowledge of court ritual, Eastern Zhou rulers declined to employ Confucius’s philosophy in governance.

In the era known as the Warring States (481–226 BCE), when only seven of the largest states had managed to survive, Confucianism was only one of many philosophies vying for patronage. The northwestern state of Qin was predisposed toward a different philosophy of government, which we call Legalism. What mattered to Legalists was tweaking administrative policies and practices so that they would serve to benefit the ruler. One of the best means of doing so was by establishing a well-publicized law code that would apply to everyone equally, regardless of social class or position. The law would reward men who undertook thankless or dangerous tasks that enriched the state, such as being a farmer or soldier, and punish those who engaged in frivolous activities that weakened the state, such as merchants, who were regarded as parasites because they produced nothing. Upon becoming Qin’s prime minister, the Legalist theorist Shang Yang (ca. 390–338 BCE) 1) created a nobility entirely based on meritorious service in warfare; 2) reorganized the Qin state into forty-one administrative districts—nobles no longer had independent fiefs; 3) organized the people into groups of five families that were collectively responsible for each family’s crimes; and 4) turned people he considered idlers into either peasants or slaves. At first many people within Qin objected to these changes, but when they saw that the laws were applied equally, even to members of the royal family, the new rules gained popular support. These reforms attracted talented administrators and soldiers from across China and made the Qin army into the most powerful military force in East Asia.

Xian as Capital of China during the Qin (350–207 BCE)

In the seventh century BCE the Qin government moved its capital from eastern Gansu Province to the western part of Shaanxi Province. Around 350 BCE, due to its impregnable defensive position, its significance as a crossroads, and its easy access to the North China Plain, Shang Yang moved the capital to the Xian area. He established the capital just north of the Wei River and called it Xianyang. Significantly, the first word of this name means “to complete” or “to unify,” whereas the second word “yang” denotes the city’s geographical position south of a mountain and north of a river.

Although Shang Yang laid the foundation for Qin to become the most powerful state in China, it was Ying Zheng (259–210 BCE), the renowned First Emperor of the Qin, who conquered the remaining six states and established China’s first imperial empire. He did so in less than ten years, from 230 to 221. To stress his singular accomplishment, he gave himself a new title, huangdi, “The August Deity or Emperor.” To run the country from the capital and rule as an autocrat, Ying Zheng abolished all independent fiefdoms and organized the whole country into thirty-six administrative districts. To oversee the empire, he created a centralized bureaucracy that had 24,000 officials and was divided into nine bureaus. In order to be able to dispatch his army promptly to any place within his territory, he made well-built roads that connected the capital to all of the frontiers. Soon his empire stretched from northern Vietnam in the southwest to western Manchuria in the northeast. To prevent rebellions, he forcibly moved 120,000 of the most influential families from the provinces to the capital region. To eliminate regional differences, he unified weights, measures, axle lengths, coinage, and Chinese written characters. True to the Legalist teachings, the First Emperor also set forth a comprehensive law that governed many aspects of life. In short, he created a centralized state based on an egalitarian law code and politically, economically, and culturally unified an area as large as the Roman Empire. Moreover, although ruling families would change, the basic governmental framework that the First Emperor forged would last until 1911. Therefore, it is no wonder that our word China is probably derived from the word “Qin.”

On its northern frontier the Qin faced people who were engaged in a relatively new form of livelihood. Between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE several groups along the northern frontier took up pastoral nomadism; that is, they became herders who each year moved with their flocks of livestock to predetermined pasturages. They lived in yurts (round tents covered with layers of felt) and ate dairy products such as milk, yogurt, and cheese. They needed to exchange their surplus animals and animal byproducts for goods and foods they could not produce themselves, such as iron, salt, and grain. If their agrarian neighbors refused to trade with them, they took what they wanted through raiding; they excelled in warfare as mounted archers. In the third century BCE, in the Ordos Region, inside of the bend of the Yellow River, there emerged a pastoral nomadic group known as the Xiongnü.

A legacy of the interaction between the pastoral nomads and Warring States Chinese was the adoption of cavalry. Our first indication of when this happened is a record of a court debate in 309 BCE, in which the king of Zhao argues that part of his army should be made up of cavalry and that the cavalrymen should be dressed in barbarian clothes—that is, a tight-fitting tunic, trousers, and boots. Interestingly, he sees this not only as a method to keep the pastoral nomads at bay but also as a way to attack other Chinese states. From this point on, all Chinese armies incorporated cavalry into their forces. In fact, the famous Qin Terracotta warriors of Xian are organized into three units: an infantry unit, a command unit in which the leaders ride in chariots, and a cavalry unit.

The Qin state had extensive contact with the pastoral nomads, but their relationship became contentious once the Qin unified China. There were so many similarities between the Qin and pastoral nomads that other Chinese states viewed the Qin as semi-barbarian. Both the Qin state and its private merchants frequently engaged in trade with the northerners. They would provide gold and silk in exchange for horses and furs. This relationship began to falter, though, during the First Emperor’s reign. To solidify his northern borders, the First Emperor’s armies drove the Xiongnü north of the Yellow River. Then, to prevent raiding, the First Emperor’s generals built a defensive wall. They did this in part by reusing the defensive walls of the old six states and in part by constructing new walls to connect the old ones. These walls went all the way from modern-day Gansu province in the far west to the Bohai Sea in the east. Today we refer to this structure as the Great Wall and think of it as continuous. However, Qin and Han people called this barrier “long walls,” made not of stone but of layer upon layer of tamped yellow earth. Elsewhere, forbidding mountains or other geographical features kept invaders out.

Of course no discussion of Qin grandeur would be complete without mention of his underground city: his mausoleum, which is located about thirty miles east of Xianyang in the town of Lintong. Qin laborers constructed a massive tumulus, or pile of earth, above his tomb known as Mt. Li. From written accounts we know that within the First Emperor’s tombs there was a miniature world with models of palaces, towers, people, and even rivers flowing with mercury. Although his mausoleum has not yet been excavated, three side pits have revealed a marvelous life-like and life-sized army of six thousand terracotta soldiers. When interred, the clay warriors were painted in multiple colors and armed with bronze weapons. Recent excavations have disclosed that there were also figurines of entertainers, civil officials, and birds, so it could well be that the tomb was a reconstruction of the world. The 1974 discovery of the Terracotta Warriors, as they are popularly known, quickly gained international attention and continues to draw travelers to Xian today.

Xian as the Forever Peaceful City in the Han (206 BCE–8 CE)

Although the governing institutions the First Emperor established would last until 1911 CE, his regime did not survive his son’s reign. In 209 BCE a number of revolts broke out across China. One rebel commander put Xianyang to the torch; there were so many palaces that they burned for three months. In 202 BCE the Western Han dynasty was founded, with its capital established south of the Wei River, a few miles northwest of Xian’s present location. This city was named Chang’an (“Forever Peaceful” or “Long-lasting Tranquility”). As the Western Han expanded into present-day North Korea and Xinjiang (also known as Chinese Turkestan) and penetrated deeper into Vietnam, this empire was even larger and more extensive than the Qin.

Each block in the city was surrounded by a tamped earth wall, each side of which had a gate. The gates were secured at nightfall so no one could go either in or out. Of course, during the day people were free to move about and meet with whomever they wished. Chang’an had 160 of these wards. Each ward had a supervisor who was in charge of the gates and twenty bao (groups of families) who were collectively responsible for each other’s behavior. The purpose of the wards was both to protect the inhabitants during times of war and to keep them under strict control during times of peace. All other Han cities were also divided into wards for the same purposes.

During the Western Han’s first half, Chang’an was a huge city that probably had 250,000 residents, but its palaces did not overwhelm the rest of the city in size or grandeur. This probably reflects the early Han rulers’ advocacy of the Warring States philosophy of Daoism. Proponents of this school believed that there was an order inherent in nature called the Dao (“The Way” or “The Path”). This order was most apparent in the unfolding of the seasons and the alternation between day and night. Those whose lives accorded with the rhythms of the Dao would prosper and live long; those whose actions contravened the Dao would fail in their enterprises and die early. As a result, people should live naturally and simply; they should lessen their desires and avoid extravagance. Daoist rulers set an example for their people through their own frugality; thus, their harems were modest, building projects few, public expenditures low, and their burials simple. In many ways Daoism was strikingly different from Confucianism: it deemphasized the importance of public service and the performance of lavish rituals and instead emphasized the importance of reclusion and simple living. Nevertheless, the two philosophies shared many concerns: both esteemed self-cultivation and leading by example, and both abhorred war. Given this overlap, the Chinese found practicing both Confucianism and Daoism easy. It is often said that a literatus was a Confucian while in office and a Daoist at home. The Western Han government’s embrace of the laissez-faire practices of Daoism generated a long period of peace and prosperity.

Shortly before the year 200 BCE, in response to being driven from their homeland, a charismatic leader named Modun unified the Xiongnü and formed them into a state headed by a hereditary leader, the Shanyu. In 198 his forces defeated a Han army. The Xiongnü state demanded gifts and trade, and the Han government signed a number of peace treaties that manifested the “Harmony through kinship” policy. In exchange for the Xiongnü not raiding, the Han government recognized the Xiongnü state as a diplomatic equal; married a Chinese princess to the Shanyu; furnished annual payments in silk, wine, and grain; and opened border markets. Although this policy secured peace for a while, the Xiongnü would often demand more. The Xiongnü state also dominated the agriculturally and commercially rich oasis cities of the Tarim Basin, which is in present-day Xinjiang Province and was an important segment of the Silk Road.

This uneasy peace lasted until the reign of the long-lived Han Emperor Wu (r. 141–87), the Martial Emperor. Desperate to find another means of dealing with the Xiongnü, in 139 BCE, he sent an envoy named Zhang Qian to the far northwest to find allies. Although unsuccessful in doing so, Zhang may have traveled as far as Iraq; he returned with an extensive knowledge of Eurasia’s peoples. Emperor Wu then decided to send large cavalry armies to attack the Xiongnü, forcing them to move north of the Gobi Desert. At the same time, to prevent them from obtaining the oasis cities’ resources, Han armies invaded the Tarim Basin; by 101 BCE Han armies conquered Ferghana (in present-day Kyrgyzstan), thereby bringing the area completely under Chinese subjugation.

By controlling the Tarim Basin, the Han now for the first time had access to the Silk Roads. The western terminuses of the silk roads were Antioch, Constantinople, and Damascus; Chang’an now became the eastern terminus. (See Map 5.2.) Given that any goods transported along the silk routes had to be carried by camel, only luxury items traveled far. Ordinary commodities were also transported but only for short distances. The most prestigious Chinese export item was silk; the Greeks in fact called China Seres, or the “land of silk.” Yet many other Chinese goods were in demand, such as lacquerware, steel products, gold and silver utensils, goods made from bamboo, peaches, pears, and oranges. At the same time, Chinese were eager to receive foreign goods, such as horses from Central Asia, sandalwood and incense from India and Southeast Asia, coral from Persia and Sri Lanka, and glass from Persia and Central Asia. Although we often think of the Silk Road connecting China with Rome, there was little if any direct contact between the two. Chinese silk commanded a high price in Rome, but it usually was shipped from the Kushan Empire, which controlled Central Asia and Northwestern India.

From the subjugation of the Tarim Basin in 101 BCE until the collapse of the Silk Road around 1750 CE, Xian was the gateway into China and the Silk Road’s eastern terminus. By means of the Silk Road China established diplomatic relations with a number of countries. The most frequent visitors were envoys from the Tarim Basin’s oasis cities. These visitors acknowledged Han’s China superiority by paying China tribute in exchange for protection and trading privileges. Other countries sent envoys, including several Indian kingdoms and the Parthian Empire in Persia. Many countries viewed sending envoys to China as a trading opportunity: the Chinese would reward the envoys with rich presents and would look the other way when they did business on the side; in fact, oftentimes foreign envoys were merchants. The Silk Road trade immensely enriched the inhabitants of Xian. Chinese merchants could buy exotic goods in Chang’an and then sell them in other parts of country at a substantial markup. Because foreigners craved Chinese-manufactured goods, such as lacquerware, the capital was also filled with workshops producing export goods. Other residents could always find gainful employment in industries that catered to foreign envoys and Chinese and foreign merchants. The state also reaped tremendous benefits from the Silk Road. Attracting foreign envoys from afar generated much prestige for the regime, especially because it reaffirmed the notion that China was the “central kingdom”—that is, the center of the world. Foreign trade also brought not only much revenue in the way of tariffs but also the luxury goods that the upper class used to distinguish itself from the rest of society.

Map 5.2. Xian and the Silk Road

Xian was the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, which connected East Asia with Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia. To ensure the security of this trade route, early Chinese governments frequently controlled the Tarim Basin. Early Chinese governments constantly came into contact with pastoral nomadic groups to the north, such as the Xiongnu during the Qin and Han dynasties and the Turks during the Sui and Tang.

Cosmopolitan Sui-Tang Chang’an (581–907)

In 316 CE, after a Xiongnü chieftain named Liu Yao seized Chang’an, it no longer served as a capital city. For the next one hundred years different steppe groups, such as the Xiongnü, the Xianbei, and the Di, established short-lived regimes that ruled over parts of northern China. By 440 a tribe from the steppes united northern China and established the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535). Four other dynasties subsequently rose and fell between 535 and 580. In 581 Yang Jian, a successful general whose family had intermarried with elite steppe families for generations, established the Sui Dynasty (581–617). He became known as Emperor Wen (r. 581–605). In 589 he conquered the last southern dynasty, thereby uniting China once again. Although the dynasty would last only until 617, Emperor Wen established the foundation on which the glorious Tang (618–907) would be built.

Emperor Wen built a new capital city, Daxingcheng, southeast of the old Han dynasty city. In 618, when the Li family overthrew the Sui and established the Tang dynasty, Daxingcheng was renamed Chang’an and continued to serve as the capital. Both the Sui and Tang Dynasties’ founders undoubtedly chose the Xian area as their capital because of its ideal geographical location: it was in a strategically important area that was also economically vibrant; moreover, one could not only dominate the Yellow River Valley from this vantage point but also control the Silk Road and its lucrative trade.

The city was so big that some precincts had more farms than people. Like its Western Han predecessor, there were three gates in each wall, and the palace city’s wall towered over them. Each of Chang’an’s main gates was in line with one of the four cardinal directions. The main avenue split the city into eastern and western sides and was an enormous 155 meters wide. Chang’an under the Tang was home to probably close to one million inhabitants.

The city’s two halves were quite distinct. The eastern half was more sedate because it had palaces and the residences of nobles. The western half was much more boisterous and active; many commoners and foreigners lived there. Each side of the city had its own official market, which was enclosed by a rammed earth wall. The Eastern Market mostly sold domestic goods, whereas the western market, which was much more active, sold foreign goods that came by means of the Silk Road. Merchants from across the empire and well-heeled citizens of Chang’an came to this market to buy precious goods such as amber, gems, glass and crystal vessels, horses, cattle, and gold and silver coins from Persia and Byzantium, which were used as jewelry. Foreign traders flocked to Chang’an to buy Chinese goods that were in high demand in West Asia. These goods included tea, porcelain, silk, paper, tapestries, embroideries, damasks, pearls, and Chinese medicines. Japanese and Korean envoys and merchants bought books in Chang’an’s used-book market. These merchants were of many different origins: Arab, Persian, Indian, Uighur Turk, and Sogdian. The marketplace was filled with “Persian shops” and “Persian workshops.” The poet Li Shangyin (813–858) maintained that the expression “poor Persian” was a contradiction in terms. Uighurs were oftentimes horse merchants or usurers. Some foreign merchants needed translators to transact business. Probably the most numerous foreign traders were Sogdians from Samarkand in Central Asia. Sogdians excelled in trading and usually could speak four or five different languages; in fact, they were so ubiquitous along the Silk Road that Sogdian became the trade route’s lingua franca. The markets were also places of entertainment, where one could take in the acts of street performers and acrobats or visit wine shops and brothels. Executions were also performed there.

Like the founder of the Sui dynasty, the founders of the Tang, Li Yuan (Emperor Gaozu, r. 618–626) and his talented son Li Shimin (Tang Taizong, r. 627–649) were generals from the northwest whose family had for generations intermarried with Steppe aristocrats. They were equally comfortable with Chinese and Turkish customs (at this time, the Turks were in Mongolia, which was their homeland). In fact, Li Shimin’s heir preferred Turkish music and dress, lived in a yurt, and surrounded himself with Turkish retainers. Unlike traditional Chinese rulers who distanced themselves from warfare and patiently waited to succeed or schemed to assume the throne, Li Shimin followed steppe customs by personally engaging in combat, ambushing two of his elder brothers, and forcing his father to retire to gain the throne. In 618 Li Shimin captured Chang’an with the aid of the Eastern Turks; he gained their help by promising to reestablish the lucrative tributary system and giving them all of the loot netted in the campaign. However, the same Turks soon became the main threat to the northern Chinese frontier. In 626 the Eastern Turks launched a raid that nearly reached Chang’an, but in 629 Li Shimin took advantage of a civil war among the Eastern Turks, launching an expedition that successfully ended their empire. In the aftermath Eastern Turkish commoners were allowed to settle in northern China while their leaders became the vanguard of Li Shimin’s army. In 640, in the Tarim Basin, they led Tang armies to victory over the Western Turks, allowing China to once again control the eastern leg of the Silk Roads. The Sino-steppe origins of the Yang and Li families allowed them to create empires that could effectively deal with northern threats. Because they had a much greater understanding of steppe culture, Sui and Tang rulers were much better at playing steppe rulers against each other and fracturing brittle tribal confederations. Consequently, Li Shimin was recognized not only as the Chinese Son of Heaven; he was also the Khan of the Turks. Given their bicultural up-bringing, Sui and Tang rulers could envision a society in which Chinese and foreigners could peacefully live side by side. It was this combination of steppe martial strength and Chinese economic and organizational resources that made the Tang the greatest power and civilization in East Asia.

GLOBAL ENCOUNTERS AND CONNECTIONS:

Cultural Convergence Creates an Ancient Melting Pot

During the Sui-Tang period China was more open than ever before to things from afar, whether it was foreign dress, music, dance, or religion. In this era an unprecedented number of foreigners lived in Chang’an. After the Eastern Turks surrendered, there were at least fifty thousand of them living in the capital. There were so many Sogdians that the government established an office of the Sogdian “caravan leader,” who enforced laws and settled disputes within his community. Foreigners were indeed everywhere in Chang’an. They owned many inns, wine shops, food shops, and bakeries. Chinese particularly liked to visit foreign-owned wine shops, where they could sip grape wine and be served by comely foreign women with green eyes. Both musicians and entertainers were frequently Central Asian or Persian. Foreigners also set up their own religious establishments: the city was home to Islamic mosques, Nestorian Christian churches, Jewish synagogues, and Buddhist monasteries as well as Manichean and Zoroastrian temples.

The Cosmopolitan Tang: Political, Social, and Religious Melding

To some extent foreigners also wove themselves into the fabric of Chinese society. Foreign merchants often wore Chinese clothes and married Chinese wives or took on Chinese concubines. No doubt present-day China’s Chinese Muslim minority, known as the Hui, had their origins in Arab and Persian merchants who married Chinese women beginning during the Tang. Foreigners also led Tang armies. In 751, deep in Central Asia at the Battle of Talas, an Arab army defeated a Chinese one commanded by a Korean general. The Tang general An Lushan, who had a Turkish mother and a Sogdian father, was an imperial favorite—that was, until he nearly ended the dynasty in a bloody revolt known as the An Lushan Rebellion (756–763); ironically, the rebellion was put down only after a Uighur Turk cavalry came to the aid of the Tang forces. Further, foreigners served in the Tang government as well as the military. In the mid-ninth century the son of an Arab merchant passed the highest test in the civil service examinations and obtained high office.

Interactions with foreigners had a profound effect on many different aspects of Sui-Tang daily life. Reflecting steppe tastes, northern Chinese favored yogurt over tea and lamb over fish. The people of Chang’an particularly loved West Asian pastries, such as pancakes, crepes, and sesame seed buns. In terms of dress, by the early Tang Dynasty nearly all men in China, regardless of ethnicity, wore the West Asian style of clothing: tightly sleeved and belted tunics, trousers, and boots. An area where foreign influence on behavior was particularly evident was in the activities of women. According to Confucian precepts, women were supposed to stay at home, keep apart from non-kin males, and, if her husband dies, never remarry. In contrast, steppe women had much freedom and played an essential public role in the life of their tribes. Sui-Tang–period women were likewise free to engage in activities outside the household; they even rode horses and learned archery. Violating Confucian mores, they sometimes had premarital sex, chose their spouse, divorced, and remarried. The Tang even had China’s only female emperor, Wu Zetian (r. 685–705), who had a male harem; by all accounts she was a very effective ruler.

Without a doubt the greatest impact that the Silk Road had on China was the introduction of the Indian religion of Buddhism. This religion affected nearly every aspect of medieval China. The grandiose Chinese literary tradition was now rivaled by its Indian counterpart. Educated Chinese had to learn a whole new literary corpus. To do so, a few learned a foreign, written language, Sanskrit, while many others struggled to master difficult concepts and words in newly translated and numerous Buddhist texts. Life-loving and worldly Chinese now also had to accept a worldview that underscored life’s effervescence and the sensory world’s unreality. Buddhism created new social groups—monks and nuns—that were outside normal society and opted out of China’s all-important family system. Monasteries too were a new social institution that soon became a significant economic player, owning a great deal of land and commanding enormous resources. Buddhism, in fact, nearly became Sui-Tang China’s national religion and caused medieval Chinese to reassess who they were and what they believed.

In conclusion, Xian has played an incredibly significant role in China’s early history. Due to mountain defenses, fertile soil, and easy access to river highways, it was simple to defend and use as a base to attack the Yellow River plain. Its easy access to the caravan routes that led west to the rich oasis cities of the Tarim Basin and beyond made it a lynchpin to east-west communications. Owing to these favorable circumstances, Xian served as the capital to five of China’s strongest and most important polities: the Western Zhou that established control over all of northern China; the Qin that unified all of what we now consider China proper; the Han that not only consolidated the Qin’s achievement but also connected China with the Silk Road; the Sui, which reestablished Chinese control over China proper; and the Tang, without a doubt one of East Asia’s greatest dynasties. Nevertheless, Xian owed much of its wealth and grandeur to the commerce that came to the city in its role as the eastern terminus of the Silk Road. Being the gateway to China brought foreign merchants to Xian, who enriched both the government through paying tariffs and bribes and the economy by bringing an insatiable appetite for Chinese goods. At the same time, the Silk Road enriched Chinese culture by stimulating hunger for new items and ideas; most importantly, it caused Chinese to wonder whether they truly were the center of the world.

The following three selections present different perspectives on life in Xian and under the Han and Tang dynasties. The first, a literary piece combining prose and poetry, reflects on the merits of Chang’an. The second relays the impressions of Chang’an by two ninth-century Arab travelers. The final document presents a fictional story from eighth-century Chinese literature that reveals patterns of daily life from that time. Each highlights the vibrant, flourishing city that was Xian during the Han and Tang dynasties.

“Two Capitals Rhapsody,” by Ban Gu

Historian Ban Gu (32–92 CE) describes Western Han Chang’an in a fu (rhapsody). Rhapsodies were literary pieces that combined both prose and poetry to describe places and objects with a tremendously varied and rich vocabulary and were often employed to praise a city. The excerpt here is a section of a larger rhapsody called the “Two Capitals Rhapsody,” in which Ban Gu describes the glorious merits of both Chang’an, the Western Han capital, and Luoyang, the Eastern Han (25–220 CE) capital. Note that he calls much attention to the geographical strengths of the area. Although obviously exaggerated, his description of Chang’an’s markets gives us a vivid sense of how popular they were. The excerpt ends by talking about the powerful local families whom the Western Han government had forcibly moved to the mausoleum towns north of the city so that the regime could keep an eye on them—they ended up producing many of the Western Han’s most important officials.

•What geographical features made Xian an ideal place for the capital?

•What was the design of the capital?

•What was life like within the city?

•Who lived in the suburbs?

There was a Western Capital guest questioning an Eastern Capital [Luoyang] host, “I have heard that when the Great Han first made their plans and surveys, they had the intention of making the He-Luo [Luoyang] area the capital. But they halted only briefly and did not settle there. Thus, they moved westward and founded our Supreme Capital. Have you heard of the reasons for this, and have you seen its manner of construction? The host said, “I have not. I wish you would

I

Unfold your collected thoughts of past recollections,

Disclose you hidden feelings of old remembrances;

Broaden my understanding of the imperial way,

Expand my knowledge of the Han metropolis.

The guest said, “Very well.” The Capital of the Western Han

Is located in [the ancient province of] Yongzhou;

It is called Chang’an.

To the east it relies on the barriers of Han Valley and the Two Yao,

With the peaks Taihua and Zhongnan as its landmarks.

To the west it is bordered by the defiles of Baoye and Longshou,

And is girdled by the rivers He, Jing, and Wei.

With its pubescent growth of flowers and fruit,

It has the highest fertility of the Nine Provinces.

With its barriers of defense and resistance,

It is the safest refuge of the empire.

Therefore, its bounty filled the six directions,

And thrice it became the Imperial Domain.

From here the Zhou rose like a dragon,

And Qin leered like a tiger.

When it came time for the great Han to receive the mandate and establish their capital:

Above, they perceived the Eastern Well’s spiritual essence;

Below, they found the site in harmony with the River Diagram’s numinous signs.

Lord Fengchun established the plan;

The Marquis of Liu [Liu Bang or Han Gaozu (r. 206–195 BCE), the founder of the Western Han] carried it to completion.

Heaven and Man acted in concordant resonance,

Thereby sharpening imperial discernment.

Then, looking around, our founder gazed westward,

And this, verily, he made the capital!

In this place

One could look out on Qin Mound,

Catch a glimpse of the Feng and Ba [Rivers],

And recline on the Longshou Hills.

They planned a foundation for one million years;

Ah! An immense scale and a grand construction!

Beginning with Emperor Gao [Liu Bang] and ending with Ping

Each generation added ornament, exalted beauty,

Through a long succession of twelve reigns.

Thus, did they carry extravagance to its limit, lavishness to its extreme.

II

They erected a metal fortress a myriad spans long,

Dredged the surrounding moat to form a gaping chasm,

Cleared broad avenues, three lanes wide,

Placed twelve gates for passage in and out.

Within, the city was pierced by roads and streets,

With ward gates and portals nearly a thousand.

In the nine markets they set up bazaars,

Their wares separated by type, their shop rows distinctly divided.

There was no room for people to turn their heads,

Or for chariots to wheel about.

People crammed into the city, spilled into the suburbs,

Everywhere streaming into the hundreds of shops.

Red dust gathered in all directions;

Smoke blended with the clouds.

Thus, the people being numerous and rich,

There was gaiety and pleasure without end.

The men and women of the capital

Were the most distinctive of the five regions.

Men of pleasure compared with dukes and marquises;

Shopgirls were dressed more lavishly than ladies Ji or Jiang.

The stalwarts from the villages,

The leaders of the knights-errant,

Whose sense of honor emulated Lord Pingyuan and Mengchang,

Whose fame equaled that of Lord Chunshen and Xinling,

Joined in bands, gathered in groups,

Raced and galloped within their midst.

One gazes upon the surrounding suburbs,

Travels to the nearby prefectures,

Then to the south he may gaze on Du [Emperor Xuan’s mausoleum] and Ba [Emperor Wen’s mausoleum]

To the north he may espy the Five Mausoleums,

Where famous cities [the mausoleum towns] face Chang’an’s outskirts,

And village residences connect one to another.

It is the region of the prime and superior talents,

Where official sashes and hats flourish,

Where caps and canopies are thick as clouds.

Seven chancellors, five ministers,

Along with the powerful clans of the provinces and commanderies,

And the plutocrats of the Five Capitals [the empire’s five foremost cities],

Those selected from the three categories, transferred to seven locations [The three categories of people selected to be transferred to the mausoleum towns were high officials, wealthy individuals, and powerful magnates],

Were assigned to make offerings at the mausoleum towns,

This was to strengthen the trunk and weaken the branches,

To exalt the Supreme Capital and show it off to the myriad states.

Source: Ban Gu, “Two Capitals Rhapsody,” in Wen Xuan or Selections of Refined Literature, vol. 1. edited by Xiao Tong, translated by David R. Knechtges, 99–109 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982).

Nubian Geography, by Abu Zayd Hasanibn Yazid Sirafi and al-Tajir Sulayman

Seven centuries after Ban Gu’s fu an Arab work known as the Nubian Geography, written by Abu Zayd Hasanibn Yazid Sirafi and al-Tajir Sulayman (tenth century), relayed the testimony of two Arab travelers who had visited Tang China. Each man went to China separately—one in 851 and the other in 867. This account shows the impressive layout of Tang Chang’an as well as how clearly segregated nobles were from commoners. Those who come to the Western Market are not the nobles or officials themselves but rather their servants and underlings.

This text was translated into French by Eusebius Renaudot (1646–1720) and then translated into English in 1733. Capitalizations of the eighteenth-century translation have been retained. Eighteenth-century spellings have been modernized, replacing “f” for “s” in necessary instances.

•What was the layout of Tang Chang’an?

•How were social strata reflected in the divisions of the city?

We asked Ebn Wahab many Questions concerning the City of Cumdan [Chang’an], where the Emperor keeps his Court. He told us that the City was very large, and extremely populous; that it was divided into two great Parts, by a very long and very broad Street; that the Emperor, his chief Ministers, the Soldiery, the supreme Judge, the Eunuchs, and all belonging to the imperial Household, lived in that Part of the City which is on the right hand Eastwards: that the People had no manner of Communication with them; and that they were not admitted into Places watered by Canals, from different Rivers, whose Borders were planted with Trees, and adorned with magnificent Dwellings. The Part on the left hand Westward, is inhabited by the People and the Merchants, where are also great Squares, and Markets for all the Necessaries of Life. At the break of Day you see the Officers of the King’s Household, with the inferior Servants, the Purveyors, and the Domestics of the Grandees of the Court, who come, some on foot others on Horseback, into that Division of the City, where are the public Markets, and Habitations of the Merchants; where they buy whatever they want, and return not again to the same Place till the next morning.

This same Traveller related that this City has a very pleasant Situation, in the midst of a most fertile Soil, watered by several Rivers. Scarce any Thing is wanted, except Palm-Trees, which grow not here.

Source: Abu Zayd HasanibnYazid Sirafi and al-Tajir Sulayman, Nubian Geography, in Ancient Accounts of India and China: By Two Mohammedan Travellers Who Went to Those Parts in the 9th Century, translated by Eusebius Renaudot, first printed in London in 1733 (New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 1995), 58–59.

The last source, Miss Ren, is an excerpt from a fictional story about a virtuous fox fairy, from a genre of Chinese literature called chuanqi (“transmitting the unusual”), in which people in ordinary circumstances happen upon the extraordinary. The author, Shen Jiji (late eighth century), was an official in the history office of the Tang Dynasty. These stories are important to the historian because their authors strived to make the narratives’ events sound as if they were plausible. They tell us not only much about medieval views of the supernatural but also the patterns of daily life. The passage below is valuable because it illustrates life in Chang’an’s residential wards, the freedom of women, social class, entertainment, and the city’s cosmopolitan flavor. Note that the Xin-an mentioned in the story is not Xian.

•How should Tang women behave?

•How does Miss Ren behave?

•What does this tell us about relations between men and women during the Tang?

•What is the social position of Cheng Sixth?

Miss Ren was a fox spirit. There was the Prefect Wei Yin, who was, on his mother’s side, grandson of the Prince of Xin-an, ranking ninth among his cousins, and who, in his youth, was wild and fond of drinking. One of Yin’s female cousins married Cheng Sixth, whose personal name I have forgotten; though accomplished in the military arts and fond of wine and women, Cheng was so poor that he had no home of his own and lived with his wife’s relations. Yin and Cheng were best of friends and quite inseparable.

In the sixth month of the ninth year (750) of the Tianbao reign, Yin and Cheng were in a street in the capital of Ch’ang-an, going together to a feast in Xinchang Ward. On reaching the southern end of Xuanping Ward, Cheng excused himself, saying that he would join Yin later, and while Yin turned eastwards on his white horse, Cheng went south on his donkey, entering the north gate of Shengping Ward. Three women happened to be walking in the street, one of whom, dressed in white, was unusually beautiful, Cheng was much attracted and contrived now to precede and now to follow them, timidity only restraining him from addressing them. But the woman in white would often look at him, as if susceptible to his attentions, whereupon Cheng said in jest, “So fine a lady should not be pacing the streets of Ch’ang-an.” The woman said laughing, “If some people who are mounted would not lend us their beast, what may we do?” Cheng then said, “A donkey is hardly fit to carry a lady, but have mine for the present. I shall be content to follow on foot.” And Cheng and the women looked at each other and burst out laughing; her companions presently joining in the exchanges, all were soon on familiar terms. Cheng followed them eastwards to the Pleasure Gardens, by which time it was dusk, and they stopped outside a gate in a mud wall, behind which rose an imposing residence. The woman in white said to Cheng, “Pray stay a moment” and went in, and one of her companions, a servant girl left behind by the gate, asked Cheng his name and rank in the family. Cheng gave his reply and proceeded to ask about her mistress, and the girl said, “She is Miss Ren, and twentieth among her cousins.” Soon afterward, Cheng was invited in. Having tied his donkey by the gate and placed his hat on the saddle, he was greeted by a woman over thirty, who turned out to be Miss Ren’s sister. Candles were lit and food spread out; the wine flowing freely, they were joined by Miss Ren, who had changed her clothes, and all three passed a merry evening, drinking to their hearts’ content. It being then late, Cheng retired with Miss Ren, whose peerless beauty, aided by her melodious voice, pealing laughter and graceful movements, made her seem divine, not of this world.

Before dawn, Miss Ren said to Cheng, “You must go! My brother, who is in the employ of the Bureau of Entertainment, is on duty in the Southern Hall of the Palace, and will come out at dawn. Do not tarry!” Having made her promise they would meet again, Cheng left. The gate of the Ward still being locked, a Tartar pastry-seller in his shop by the gate had just lit his lamp to start a fire in the stove, and while waiting for the drum to sound, Cheng took shelter under the pastry-seller’s curtain and chatted to the man. Pointing in the direction of the place where he had spent the night, Cheng said, “If you turn east from here, you will see a gate; whose house does it open into?” The pastry-seller replied, “It is all waste land behind a wall; there is no house.” Exclaiming, “But I just passed a house! Why do you say there is none?” Cheng began to argue heatedly with the man, who suddenly nodded to himself and said, “Oh, I know what it is! There is a fox here who lures men to her lair in the waste ground. I have seen it happen three times. I suppose you, too, have been enticed by her.” Ashamed, Cheng denied this, and when it was broad daylight, went back to the spot and found the gate and mud wall, though which he glimpsed only a neglected market garden overgrown with weeds.

Source: H. C. Chang, Chinese Literature 3: Tales of the Supernatural (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), 45–47.

Di Cosmo, Nicola. Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Kiang, Heng Chye. Cities of Aristocrats and Bureaucrats: The Development of Medieval Chinese Cityscapes. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1999.

So, Jenny F., and Emma C. Bunker. Traders and Raiders on China’s Northern Frontier. Seattle and London: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery & University of Washington Press, 1995.

Whitefield, Susan. Life along the Silk Road. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999.

Wu Hung. Monumentality in Early Chinese Art and Architecture. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995.

Xiong, Victor Cunrui. Sui-Tang Chang’an: A Study of Urban History in Medieval China. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 2001.

Xue Pingshuan. “The Merchants of Chang’an in the Sui and Tang Dynasties.” Frontiers of History in China 2 (2006): 254–275.

Zou Zongxu. The Land within the Passes: A History of Xian. Translated by Susan Whitfield. New York: Viking Press, 1991.

A Digital Reconstruction of Tang Chang’an, www.sde.nus.edu.sg/changan/#.

A Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, http://depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/.