At the end of 1954, the golden year when the Lucas family first acquired a television, Disney aired four one-hour films about the life of a Tennessee congressman who lost his life in the Alamo. The company was caught off guard by the show’s popularity, which led to an incredible $300 million merchandising bonanza in the space of a year. Kids went wild for the show’s hero, pestering parents to buy his toy guns, sheets, watches, lunch boxes, underwear, mugs, towels, rugs, and pajamas. Most especially, they bought his headgear, a coonskin cap, which reportedly sold at a rate of five thousand caps per day in 1955 alone. The price of raccoon fur jumped from 25 cents to $8 a pound.

Most of the windfall went to independent sellers; at the time, licensing as we know it today simply didn’t exist. But the young Lucas saw the results all around him, stored the example away in his memory, and would draw on it some twenty-one years later as he labored over his third film.

In 1976, talking to Lippincott after shooting Star Wars, Lucas cast his mind back to this 1950s craze. He was trying to explain how his movie might just be the first feature film to have an impact in merchandising, and this Disney TV miniseries was the biggest merchandising hit in his memory.

“Star Wars,” Lucas mused, “could be a type of Davy Crockett phenomenon.”

That, of course, turned out to be the understatement of the century.

To understand the degree to which Lucas’s creation outstripped Davy Crockett, to see the true scope of four decades of Star Wars’ physical presence—both its merchandise and fan-created gear—you need to visit a chicken ranch in Petaluma, Northern California.

Appointments are required to enter through the ranch’s wrought-iron gate, which is adorned with a portrait of Alec Guinness. You park by flagpoles flying the banners of the rebellion and the Empire, and walk past the private home that says “Casa Kenobi.” There used to be twenty thousand chickens on this property; now there are fewer than six in a single coop, near the corner of Yoda Trail and Jedi Way. The others have been replaced, in a long former chicken barn, by what the Guinness Book of Records recognized in 2013 as the world’s largest Star Wars collection. Welcome to Rancho Obi-Wan.

Up a narrow stairway Steve Sansweet greets you near an alcove with a talking head of Obi-Wan. The bust looks like Guinness, Obi-Wan number 1, but it has the prerecorded voice of James Arnold Taylor, Obi-Wan number three, from the Clone Wars cartoon. “Your visit may provoke feelings of intense jealousy,” the voice warns. “But do not give into hate. That leads to the Dark Side. If you’re lucky, you won’t also give in to a spending spree. So get ready for a galactic, physical and spiritual reawakening . . . from a certain point of view.”

Sansweet is snarky and avuncular, bursting with knowledge—he cowrote the official Star Wars Encyclopedia, the Ultimate Guide to Star Wars Action Figures, and many more besides. He’s somewhere between a vaudeville comedian and a gossip, always ready with a quip and another collector’s item to show you. With bushy black eyebrows framed by a silver beard, he looks like a mischievous Santa Claus. You might think him a retired TV host, which in fact he is: he helped QVC sell Star Wars gear during sixty hours of shows during the 1990s. “And I always bought one of whatever I was selling,” he says. He’s not kidding.

Sansweet was raised in Philadelphia, went to journalism school, and reported on the JFK assassination for the college paper. As a Wall Street Journal reporter in Los Angeles in 1976, he started collecting toy robots after writing a front-page story about a collector; the robots reignited a long-held passion for science fiction. Then one day at the office, he noticed another reporter toss an invitation in the trash. It was to the media preview of a new movie called Star Wars. Sansweet fished it out, and a few days later his life changed forever. That invite, and the movie program, are the first items in his collection. “I was already in my 30s,” he wrote, “but realized this was what I had been waiting my whole life for.”

Sansweet had to wait another twenty years until he could parlay his love of Star Wars into a job at Lucasfilm, as head of fan relations. By then his house in LA had gained an extra two floors and five storage lockers, all to hold his collection. And that was before the prequel movies, which saw by far the largest explosion in Star Wars merchandise in the franchise’s history. Sansweet is a collecting machine: a scavenger of sets, a friend to every licensee and fan artist. He swoops on eBay offerings and divorce sales. He has a black belt in price negotiation. There’s a poster in his office, signed by George Lucas, which confers on Sansweet the title of “ultimate fan.”

At first, Sansweet was determined to keep his collection private. His Petaluma chicken farm, the only place his real estate agent could find near Skywalker Ranch that was large enough to hold his stuff, was too remote to seriously consider turning it into a museum. But after leaving Lucasfilm in 2011 (he’s still a part-time adviser), Sansweet was convinced by friends that there was enough interest to convert the place into a nonprofit. It would offer regular tours for anyone who takes out a membership. With just two employees, Rancho Obi-Wan already has one thousand members, paying $40 a year each.

Sansweet provides a quick tour of the library—which contains books from thirty-seven countries in thirty-four languages—and the art and poster room, where all the unopened boxes live. His assistant, Anne Neumann, is usually to be found here, still struggling to catalog everything in the collection; her official estimate, after seven years and ninety-five thousand items catalogued, is that there are at least another three hundred thousand items and counting. To put that in perspective, the British Museum has fifty thousand items on display at any one time.

We travel down a cramped corridor of movie posters, and you can’t help but wonder where the real goods are. Then Sansweet knocks at a door. “Mr. Williams,” he says, “are you ready for us?” Then in a stage whisper, he adds: “Very temperamental.”

As the door swings open and John Williams’s Star Wars theme begins, you gaze down the stairs at what a twenty-first-century type of Davy Crockett phenomenon looks like.

It’s the large items you notice first: the life-size Darth Vader with red lightsaber drawn (codpiece and helmet from the original costume), the original mold of Han Solo in carbonite, the larger-than-life Boba Fett, the head of Jar Jar Binks, the stuffed Wampa, an animatronic version of the Modal Nodes band from the Mos Eisley cantina, the iconic bicycle from Skywalker Ranch with lightsabers for handlebars and a Vader-shaped bell (known as the Empire Strikes Bike).

Seconds later, as your eyes adjust, you take in the rows upon rows of stuff. It’s packed tightly into shelves as if it were a department store where space is at a premium—except the space seems to go on forever, with at least two sets of shelves on every wall, vanishing into the distance, where stands a life-size Lego Boba Fett and a Star Wars marquee from 1977. There are rooms beyond that, just out of sight: a corridor constructed to look like one on the Tantive IV leads to the artwork, the arcade games, the pinball machines.

This is the point at which grown men and women have been known to weep. It is also the point at which one of two things tends to dawn on their partners: “I get it now,” and “Okay, maybe that collection at home isn’t so bad after all.”

Star Wars has generated more collectable paraphernalia than any other franchise on the planet—but it had surprisingly little help from its creator. At some point in 1975, working on the interminable second draft and sipping coffee, George Lucas thought of dog breed mugs. They were all the rage in the 1970s. Wouldn’t it be fun to have a mug that looked like a Wookiee? That, and the fact that R2-D2 looked like a cookie jar, were the only specific pieces of merchandise that Lucas has admitted envisioning while writing the film.

But Lucas knew the movie was ripe with possibilities for spin-off products. Having grown up the son of a stationery and toy store owner, having constructed his own toys, he remained fascinated by their potential and wasn’t the least bit ashamed of his interest. When the director George Cukor told Lucas at a film conference in the early 1970s that he hated the term “filmmaker” because it sounded like “toymaker,” Lucas shot back that he would rather be a toymaker than a director, which sounded too businesslike. Movie sets were play sets; actors were action figures. “Basically I like to make things move,” he said in 1977. “Just give me the tools and I’ll make the toys.” Toys “followed from the general idea” of Star Wars, he told a French reporter later that year.

Before Star Wars, no one had ever made a dime out of toy merchandising associated with a movie. The previous attempt had accompanied Doctor Dolittle in 1967, when Mattel produced three hundred Dolittle-related items, including a line of talking dolls in the likeness of Rex Harrison and his menagerie. The producers licensed multiple soundtrack albums, cereals, detergents, and a line of pet food. They placed toys inside puddings and waited for the revenue to roll in.

Even though Doctor Dolittle was a hit, an estimated $200 million of its merchandise went unsold. And this problem with movie merchandise was not limited to the pre–Star Wars era. The Doolittle tale was to repeat itself with ET in 1982. ET was wildly successful—it overtook Star Wars in the all-time box office stakes (at least until the Special Editions were released at the end of the next decade)—but ET computer games and toys in the shape of the movie’s alien protagonist had been overproduced and gathered dust on store shelves. Atari produced so many unsold ET game cartridges that it decided to bury them in a giant pit in the New Mexico desert. The movie was a charming story; it was not, as industry parlance had it, a particularly “toyetic” story. The protagonist did not look especially cute in the cold light of Toys “R” Us.

In retrospect, of course, it seems obvious that Star Wars was the very definition of toyetic. The characters and vehicles were profoundly unusual, the uniforms (plastic spacemen!) bright and arresting, the blasters and lightsabers mesmerizing. Had it been a TV show, merchandising deals would have been no problem. Just look at the Star Trek toys, the dolls, the Starfleet napkins, the Dr. Pepper tumblers featuring Kirk and Spock that you could pick up at any Burger King in 1976. But Star Wars was a movie, not a TV show, and every toy executive in the mid-1970s knew that movies were here today and gone tomorrow. By the time manufacturers got their toys made in Taiwan, Star Wars would most likely be out of theaters and forgotten.

Still, as the release date approached, Lippincott persisted. He tried to sell toy companies on the then-bizarre idea of Star Wars action figures. His top target was the Mego Corporation, which produced Action Jackson and a line of World’s Greatest Superheroes. But the movie wasn’t finished until the last minute, and with only still photographs from the film available for pitching potential merchandising partners, Lippincott struck out. Mego was importing a line of action figures from Japan called Micronauts. They were the best-selling toys in America. Who needed Star Wars? At the February 1977 toy fair in New York, Lippincott was asked to leave the Mego Booth.

Finally, Lippincott got a bite from a Cincinnati-based company called Kenner, which had invented the Easy Bake oven in 1963 and had just found success again with twelve-inch Six Million Dollar Man dolls. Kenner was owned by cereal company General Mills. The toy company’s CEO, Bernie Loomis, had been persuaded by the Star Wars deal simply because Fox dangled the possibility that Star Wars might be made into a TV show. Loomis and Lippincott signed a contract that committed Kenner to producing four action figures and a “family game.”

The terms of that deal, signed a mere month before the release of the movie, have never been revealed. Mark Boudreaux, a designer who started working at Kenner in January 1977 and was thrust straight into making vehicles for the Star Wars line, remembers the deal being described around the office as “$50 and a handshake.” Certainly, Lucas—who had been too busy finishing the film to micromanage Lippincott—was furious when he found out what he’d been locked into once the movie came out. “He thought he should have had more of the money,” Lippincott says. “But we made it at a time when nobody wanted a toy deal. The Monday morning quarterbacks say we should have waited. I don’t think anybody could have.”

In the lead-up to the film’s release, Lippincott gave Kenner the trailer for the movie. The toy designers went wild for it, and set about making three-and-three-quarter-inch action figures. One story has it that the figures were that size because Loomis asked his vice president of design to measure the distance between his thumb and his forefinger. In fact, the figures were simply the same size as Micronauts. Star Wars dolls couldn’t be the standard eight or twelve inches tall; they had to fit in vehicles. If Han Solo was twelve inches tall, the Millennium Falcon would have to be five feet wide. Toys “R” Us would have had to take over the entire mall. Instead, Star Wars toys would have to be content with taking over entire walls of stores.

For that first holiday season, Kenner couldn’t swing into action fast enough. Scrambling in early June when it was clear the movie was a monster hit, the company would have needed to start shipping the action figures in August to make it in time for Christmas, an impossible deadline at the time. A very junior designer at the company, Ed Schifman, came up with an infamous solution: a $10 piece of cardboard that promised you the first four action figures as soon as they were ready. It was called the “Early Bird Special.” Some fans mock it, some remember it fondly, but there’s no denying it did the trick. “Okay, we sold a piece of cardboard,” says Boudreaux. “We still kept Star Wars toys top of mind at Christmas 1977.” (Like just about every action figure in Star Wars history, the Early Bird Special was too famous to produce just once: in 2005, Walmart sold a replica version.)

Once it was clear Star Wars was a hit, Lucas sat down with Kenner and made sure there would be other toys beyond the action figures. Top of his mind: blasters. Loomis had banned guns from the Kenner line after Vietnam; the generation that protested the Vietnam war were now parents and were horrified by the prospect of their kids playing with weaponry. Loomis tried to tell Lucas this. Loomis was planning on making inflatable lightsabers, so at least the kids could do battle with something. Lucas took this all in, then repeated his question: “Where are the guns?” Loomis relented; Kenner started selling blasters.

In 1978, the company sold more than forty-two million Star Wars items; the majority, twenty-six million, were action figures. By 1985, there were more Star Wars figures on the planet than US citizens. Then came a lull of a decade, before a new licensee, Hasbro, came along with the “Power of the Force” line; though the figures were derided (by Sansweet, among others) as being ridiculously muscular, they still sold like hot cakes. Hasbro hasn’t left off since.

After 1977, Lucas started to develop some hard-and-fast rules about the Star Wars brand. The hardest and fastest was that the Star Wars name was not be slapped on any old piece of crap. The movies were made with incredible care and precision; the merch should be too. Sansweet can show you a prime example made by Kenner’s Canadian division in 1977, which hadn’t got the memo: a Batman-style utility belt and a dart gun, with Darth Vader’s image on the box. Lucas was enraged when he saw it. His licensing division, then called Black Falcon, was supposed to ensure that sort of thing never went on sale again. It nixed the Weingeroff jewelry deal. Star Wars was also never to be associated with drugs or alcohol. (There were exceptions to all these rules in the chaotic beginning; Sansweet gleefully shows off a piece of sheet music from 1977, the cantina band theme, that shows Chewbacca with a martini glass.) Until Lucas relented in 1991, there would not be Star Wars–themed vitamins for fear that children might get a taste for pill popping (the maker of THX 1138 still resented drugs).

Lucas professed to take a hands-off approach to merchandising, but in practice he retained a tremendous amount of control over it. “If you do something I don’t like, I’ll let you know,” he told Maggie Young, Lucasfilm’s vice president of merchandise and licensing from 1978 to 1986. As a management technique, that did the trick: Young was too terrified to make anything but the most conservative choices. There do seem to be a few strange blind spots in the history of licensing: Lucas, a diabetic, held out against sugary breakfast cereals for years (until Kellogg pitched low-sugar 3POs in 1984), even though some of Star Wars’ most long-term partners included sugar water makers Coca-Cola and Pepsi.

Inconsistency aside, it worked. More than $20 billion of merchandising has been sold over the lifetime of the franchise. That’s half the lifetime sales of the Barbie franchise—quite a feat, considering that the anatomically unrealistic blonde doll had a twenty-year head start. And Barbie is struggling to remain relevant in the modern world; the doll’s sales declined by 40 percent in 2012. Star Wars, meanwhile, is only getting stronger; now that Disney, a publicly traded company, has bought the formerly private Lucasfilm, we know that it generated about $215 million in licensing revenue in 2012 alone.*

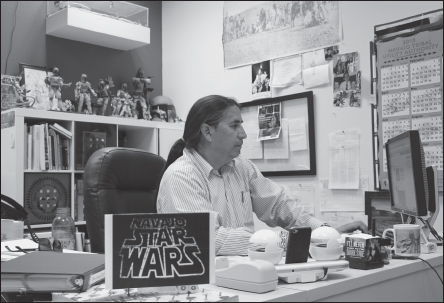

Manuelito Wheeler, Director of the Navajo Nation Museum, with a scale model of the truck-mounted screen he used to show the first movie in the Navajo language: a little something called Star Wars, to which his office is a shrine. CHRIS TAYLOR

Fascination with the space frontier mixes with nostalgia for an age of chivalry in this publicity still for Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe. In the cockpit of their rocket ship, dressed for the region of Arboria, from left: Dr. Zarkov (Frank Shannon), Flash Gordon (Buster Crabbe), Dale Arden (Carol Hughes), and Prince Barin (Roland Drew). UNIVERSAL PICTURES

In 2013, George Lucas made his one and only public homecoming to Modesto for the fortieth anniversary of American Graffiti, down the streets he used to cruise—and here, past his father’s old stationery and toy store. Asked if Modesto was the home of Star Wars, he responded: “not really. Most of these things come from your imagination.” CHRIS TAYLOR

Albin Johnson, founder of the 501st Legion, is a shy, retiring, behind-the-scenes kind of guy—not that you’d know it from this rare shot of Albin with a couple of what he calls “Trooper Groupies.” ALBIN JOHNSON

Mark Fordham, then-CO of the 501st and its premiere Darth Vader, shows the power of the Legion at the Tournament of Roses Parade in 2007, with Grand Marshall George Lucas. Both men had ambitions to turn their organizations into franchises. MARK FORDHAM

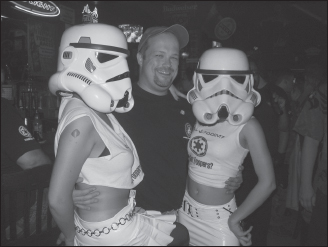

The day that changed everything and eventually birthed Star Wars: June 12, 1962. The crash quelled George Lucas’s driving desires, committed him to education, and led to a love of anthropology, sociology, and the visual arts. THE MODESTO BEE

A rare portrait by photography student Lucas, never before published, shows his love of dramatic lighting. The rock guitarist subject is Don Glut, fellow member of the Clean Cut Cinema Club at USC and future author of the Empire Strikes Back novelization. COLLECTION OF DON GLUT

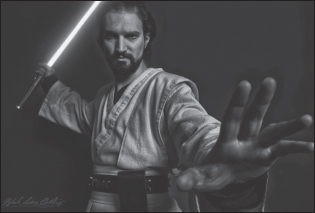

Alain Bloch, co-founder of the Golden Gate Knights, teaches a weekly three-hour lightsaber class—a cross between fencing and yoga, with a few moments to meditate on the Jedi Code. Jedi organizations tend to be action-oriented more than spiritual. CRISTINA MOLCILLO AND ROS’IKA VENN

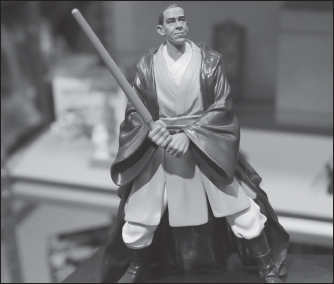

A fan-made model of Barack Obama as a Jedi, seen at Rancho Obi-Wan. Obama is the first president to have been a teenager when Star Wars hit theaters. He crossed lightsabers with the US Olympic fencing team, responded to a petition requesting a Death Star, and was dubbed a Jedi Knight by George Lucas—then confused a Jedi mind trick with a Vulcan mind meld. CHRIS TAYLOR

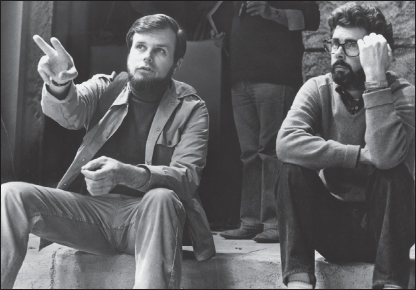

Gary Kurtz, here with Lucas on the throne room set from Star Wars, was four years Lucas’s senior and had the Vietnam experience he was looking for in a producer for Apocalypse Now. But he was also a Flash Gordon fan, and ended up producing a remarkable string of hits for Lucas instead: American Graffiti, Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back. His level of influence over the early franchise, before his sudden departure from it, is still debated. KURTZ/JOINER ARCHIVE

Phil Tippett and Jon Berg were recruited to help reshoot the aliens in the Cantina. When George Lucas found out they were also stop-motion artists, he asked them at the very last minute to animate the chess set on the Millennium Falcon. Previously, Lucas had planned to use actors in leotards for the chess pieces. TIPPETT STUDIOS

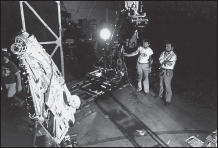

The Millennium Falcon, the Dykstraflex, Richard Edlund, and Gary Kurtz at ILM in 1976. The homemade computer-controlled camera was the hidden hero of Star Wars, creating the illusion of multidirectional spaceship motion for the first time—and turning the moribund special effects industry on its head. KURTZ/JOINER ARCHIVE

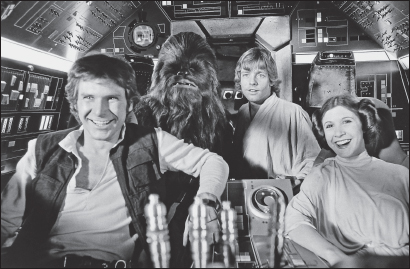

The bright, compelling cast that, according to Carrie Fisher, used to jokingly call itself “trick-talking meat”: Harrison Ford (Han Solo), Peter Mayhew (Chewbacca), Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker), and Fisher (Princess Leia). KURTZ/JOINER ARCHIVE

The wait outside the 1,350-seater Coronet in San Francisco on the weekend after opening, May 28, 1977. It took three days after the movie opened for newspapers to start photographing the lines outside theaters across America. CORBIS / SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE

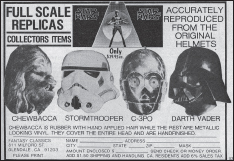

The first Star Wars merchandise ad ever to grace the pages of the science fiction magazine Starlog, in the issue that hit stands July 14, 1977. These vinyl masks (and Chewbacca’s “hand applied hair”) were some of the first products licensed by Twentieth Century Fox, which at this stage had just as much right to sell Star Wars tchotchkes as Lucasfilm did. STARLOG/INTERNET ARCHIVE

Mann’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood, where Threepio, Artoo, and Darth Vader placed their feet in wet concrete in August 1977. The ceremony celebrated the return of Star Wars after a mercifully brief engagement with what was supposed to be the hit of the summer, William Friedkin’s Sorcerer. A few hundred attendees were expected; five thousand showed up. KURTZ/JOINER ARCHIVE

Lucasfilm veteran and ultimate fan Steve Sansweet now holds the Guinness World Record for the largest Star Wars collection ever. His nonprofit museum Rancho Obi-Wan boasts 300,000 items, such as this 8mm one-scene viewfinder, the closest audiences in the 1970s could get to taking the movie home with them. CHRIS TAYLOR

The author dressed in a Boba Fett costume, hand-crafted by the 501st Legion, wandering the halls of the Salt Lake Comic Con in 2013. CHRIS TAYLOR

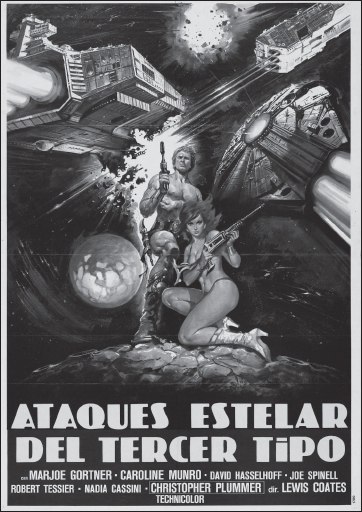

Of all the Star Wars rip-offs, by far the most blatant was Italian cult classic Star Crash, seen here in a Spanish-language version. The movie featured a lightsaber battle and a planet destroying super weapon; the poster boasted what appeared to be a Star Destroyer and the Millennium Falcon. The title translated to “Star Clashes of the Third Kind.” NEW WORLD PICTURES

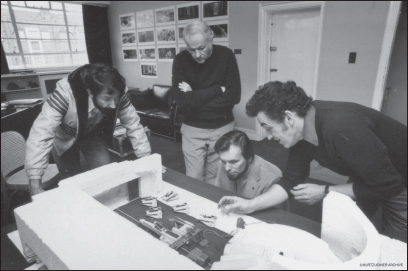

Cinematographer Peter Suschintzky, artist Ralph McQuarrie, Gary Kurtz, and production designer Norman Reynolds discuss an early scene in The Empire Strikes Back over a maquette of the Rebel Base hangar on Hoth. KURTZ/JOINER ARCHIVE

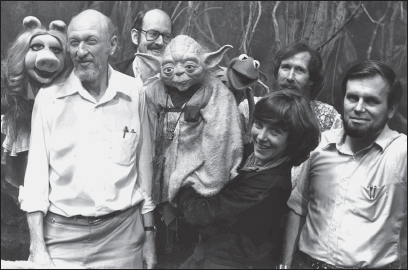

The Dagobah set at Elstree hosted a few special visitors from their Borehamwood neighbors, the Muppets—and you can see just how little love was lost between The Empire Strikes Back director and his little green star. From left: Miss Piggy, Irvin Kershner, Frank Oz, Yoda, Kermit the Frog, Kathy Mullen, Jim Henson, and Gary Kurtz. George Lucas consciously based Yoda on Kermit; this was their first meeting. Both characters are now owned by Disney. KURTZ/JOINER ARCHIVE

Jeremy Bulloch, aka the original Boba Fett, poses with two astromech droids at Celebration Europe II. CHRIS TAYLOR

The main room at Rancho Obi-Wan in Petaluma, California. CHRIS TAYLOR

Cast members from Return of the Jedi reunite on stage, months before it is announced that four of them would be returning for Star Wars: Episode VII in 2015. At this point prior to his operation, one of the returning cast, Peter Mayhew (Chewbacca), is unable to walk without the use of a lightsaber cane. CHRIS TAYLOR

The only photograph taken of the historic one-time meeting between Gene Roddenberry, creator of Star Trek, and George Lucas, creator of Star Wars. At “Starlog Salutes Star Wars,” the tenth anniversary celebration at the Stouffer Concourse Hotel in Los Angeles, May 1987. DAN MADSEN

The fans who became buddies for life after they camped outside the Coronet theater in San Francisco for what was then a record thirty-three days before the release of Episode I: The Phantom Menace. Most would not look this excited after seeing the film. CHRIS GIUNTA

Artoo builder Chris James and an army of astromechs. The entirely fan-built droids range from the original-style R2 Unit to the black-domed R4-K5—a dark side droid said to work with Darth Vader in one Star Wars novel. CHRIS JAMES

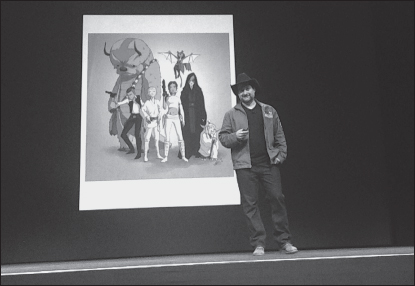

Star Wars: the Clone Wars director Dave Filoni shows a picture he drew while an animator on Avatar: The Last Airbender, of that show’s characters in Star Wars garb. A hardcore fan of the franchise from age 3, Filoni almost didn’t get the Star Wars directing job—because when Lucasfilm called, he thought it was a prank committed by friends at Spongebob Squarepants. CHRIS TAYLOR

Eight years after narrowly escaping arrest for wearing a Darth Vader costume when the character was completely unknown, Turkish 501st Legion founder Ates Cetin finds himself leading a protest towards Taksim Square in 2013 while protesters hum the Imperial March. GIZEM AYSU OZKAL

The museum that never was: the original rejected plan for the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum or LCAM, permanent home for much Star Wars artwork, on the waterfront of San Francisco’s Presidio. LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM

Sansweet is quick to correct anyone who might have worried that the sale of Lucasfilm to Disney would lead to a sudden slew of Star Wars Disney products. “People got all upset online and complained they were going to make Darth Goofy,” he says. “Well, guess what—they made it seven years ago, and it was great.” He points to his shelves of Jedi Mickeys, Stormtrooper Donald Ducks, and yes, Darth Goofy—fruits of a twenty-five-year partnership between Lucasfilm and Disney.

Sansweet’s tour seems unending, and he likes to keep it unpredictable. You never know when he’s going to pick up a plush puppet of Princess Leia in her slave bikini, say, and start talking in a falsetto voice, or threaten you with a felted wool blaster. Often he affects bafflement about the items in his collection, as if he just woke up to find all this stuff here. He will mock unusual objects no matter where they came from, and he’s delighted to show off some of the worst official products ever to emerge from Lucasfilm licensing: a C-3PO tape dispenser where the tape emerges suggestively from between the golden droid’s legs; a Williams Sonoma oven mitt in the shape of the space slug from Empire Strikes Back; Jar Jar Binks candy where you have to open the Gungan’s mouth and suck on his cherry-flavored tongue. Sansweet shakes his head sadly, suppresses a smile. What were they thinking?

But the officially licensed Star Wars products are incomparable—both in terms of numbers and strangeness—to the paraphernalia that fans and bootleggers have produced. Sansweet can show you some of the earliest bootlegged figures, replicas of which—replicas of bootlegs!—now go for hundreds of dollars. A good chunk of Rancho is given over to fan-made ephemera from around the world. We’re talking a beautiful Bantha piñata and Leia and Han as Day of the Dead skeletons from Mexico; tins of Cream of Jawa soup and potted Ewok; a Stormtrooper painted on a ten-thousand-year-old mastodon bone. There are dozens of tricked-out Stormtrooper and Vader helmets, each one painted by a different artist for the Make-a-Wish foundation. Australian fans studiously ignored Lucasfilm’s alcohol ban and sent Sansweet a bottle of Mos Eisley Space port.

“The fan-made stuff turns me on more than anything,” says Sansweet. “It shows their passion, their skills, and what sets Star Wars apart from any other major fandom of the last fifty years. I love Harry Potter, but you don’t see people building miniature Hogwarts castles. You don’t see a lot of kit Quidditch teams. People love those movies. They don’t have the same passion for them.”

Being around Steve Sansweet—here at the Ranch, at a book signing, laughing and backslapping with fans at Celebration—is like living in a Star Wars–themed version of The Orchid Thief. Except that Sansweet’s obsession is more stable, more legal, and more constantly fed than John Laroche’s pursuit of rare flowers. It’s hard not to be jealous of Rancho Obi-Wan—not necessarily of the collection itself, though I have met many people who would kill to own it, but rather of the kind of certainty and focus it reflects. To be immersed in an unrivaled global network of fandom, with merchandising as your MacGuffin. To be the ultimate fan—yet to still retain a finely tuned sense of the ridiculous. To shake your head at the folly and still love every second of it. This is a big part of the idea of Star Wars.

I have never been a collector of anything—I generally align myself with the view expressed by Dr. Jennifer Porter, the Jedi academic and religion expert, who described the kind of gear she saw at Disney’s Star Wars weekend as akin to “tacky pilgrim mementos from Lourdes” that people have a disturbing tendency to “cherish as contact with the sacred.” Still, Star Wars is about the closest I ever got. I started buying the action figures and receiving them as gifts in 1980, just in time for The Empire Strikes Back. In those days before video rentals, before Star Wars had even been shown on network TV, the figures were a way of taking little pieces of the movie home—even when the figure in the plastic blister pack looked significantly more generic than the actor on the cardboard back of the packaging.

Just as importantly, the figures were a way of feeding my imagination in the absence of new Star Wars movies. The three-year wait between the Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi seemed interminable. There were innumerable ways the cliff-hanger ending of Empire could have worked out. My figures, and millions of others around the world, played out the possibilities. Countless Millennium Falcons chased after Slave-1, the ship owned by Boba Fett, which came with a free Han Solo frozen in carbonite. Who knows how many times Luke Skywalker—the Cloud City version—repeated his showdown with Darth Vader’s figure, demanding to know if what he said about being his father was true?

One thing that would never have crossed my mind as a kid was keeping the figures pristine in unopened blister packs. That was what I feared seeing at Rancho Obi-Wan: an unhealthy obsession with mint-condition collecting and trading, the joyless commodification of playthings. So I was glad to learn from Hasbro, which bought Kenner in 1991, that the majority of Star Wars consumers don’t take that approach. “About 75 percent of our fans do liberate their figures,” says Derryl DePriest, Hasbro’s vice president of global brand management and chief evangelist for the Star Wars line, who conducts surveys on these sorts of things.

DePriest has been liberating his Star Wars figures since the age of twelve. When I first met him at San Diego Comic-Con, he pulled out his smartphone and showed me how he stores his collection at home. They were arranged on dozens of shelves, each shelf representing a major ensemble scene from a Star Wars movie. You could reenact the original trilogy in three and three-quarter inches, right there. (It was the first time I’d seen something Rancho Obi-Wan actually didn’t have.)

As DePriest thumbed through his photos, I pointed out a shelf full of Stormtroopers surrounding the Millennium Falcon, and recalled that one of the most puzzling things I had done with my collection as a child was to trade a Snowtrooper from the Hoth base in The Empire Strikes Back for a friend’s regular Stormtrooper figure, one that was more beaten up than the regular Stormtrooper figure I already had. It’s hard for an adult to remember what kind of logic was at work there: Aren’t collectors supposed to crave the dissimilarity of collector’s items? But DePriest was able to absolve me and reminded me why I did it: everyone needs a whole bunch of Stormtroopers. “Part of the fun is having the good guys outnumbered by the bad guys,” he said. “The rebels always have to be fighting against an overwhelming force. So we make sure we have those figures in abundance.” Call it the spirit of the 501st in miniature. No trooper should troop alone.

Despite this inherent advantage, the Stormtrooper is only the second-best selling action figure in Hasbro’s line. Consistently on top, year after year, is Darth Vader. We’re drawn to the iconic villain, it seems; no wonder Lucas evolved him from a second-tier role in the original Star Wars, with little more than ten minutes of screen time, to the centerpiece of the first six movies.

As the technology of model making improves, Hasbro is able to sell more and more varieties of Star Wars action figures—and Vader is the primary beneficiary of this shift. This is quite a shock for a casual fan from the 1970s and 1980s, when there was only one model of Vader sold (because why would you make more when the guy never changes his costume?). From 1995 through 2012, there were fifty-seven new versions of Vader, and that’s not even counting the dozens of Anakin Skywalkers produced during that time. Those on the light side of the Force will be glad to know that Luke has his dad beat in sheer numbers, with a grand total of eighty-nine figures in every conceivable costume and pose. Sadly, Princess Leia has a mere forty-four figures in her name. In total, there are now more than two thousand kinds of Star Wars figures—a far cry from the three hundred sold by Kenner.

I put the latest Hasbro figures next to my old Kenner models; it was like looking at a Rembrandt next to a medieval fresco. The old figures, so vibrant in my youth, now seemed like blobs of plastic with eyes and a mouth drawn on. Their twenty-first-century counterparts were exquisitely crafted miniature humans. DePriest explained that Kenner’s factories in China used to crank out millions of figures from the same plastic mold. As the molds degraded, the figures looked less and less screen-accurate. The factories were rushing to feed a phenomenon that could have collapsed at any moment. These days, with Star Wars on a stable footing, the molds are precision-made and can be changed every few hundred figures.

Star Wars has proved to be a strong prop for Hasbro. In 2013, the company scored a hit by collaborating with videogame company Rovio on Star Wars Angry Birds. In one month, the company sold a million Star Wars ‘telepods’—physical toys that interact with the app. Not only does the company have a range of figures in the works for Episode VII, it still has figures left over from the first six movies that have never been made. You may think every single character in every single scene has been made into an action figure by this point, but DePriest says there are still plenty of aliens from the cantina and Jabba the Hutt’s Palace that have never seen the inside of a plastic mold.

Still, the real money is in the more popular characters and in making ever more precise, screen-accurate versions of them you can sell to collectors. There are whole teams at Hasbro dedicated to doing just that. At Comic-Con, DePriest showed off a forthcoming figure, a $20 version of Princess Leia in her eye-opening slave bikini from Return of the Jedi. The blueprints were covered in notes to the design team: “Eyes should be more sultry. More petite overall. Smaller breasts. Outer parts of nostrils not so tall. Please sculpt some underpants!” I couldn’t help but think of Carrie Fisher’s acerbic attack on a Leia model she once received that seemed a little too revealing. “I told George, ‘You have the rights to my face,’” she said. “You do not have the rights to my lagoon of mystery!’”

But the audience of collectors, men and women, were thrilled. Then DePriest asked how many of them actually take their figures out of the packaging when they buy them. Only a smattering of hands went up.

“Play with your toys, people,” DePriest sternly told the crowd. “Play with your toys.”

________

* Barbie can’t even count on strict gender divisions in toys any more—certainly not since Wear Star Wars, Share Star Wars Day was started by blogger Carrie Goldman in 2010. Goldman was incensed when her daughter was bullied for bringing a Star Wars water bottle to school, and she struck back with an annual event promoted far and wide online, designed to draw attention to the fact that girls love Star Wars too.