As pointed out in the previous chapter, salt fish has been very important to the world’s expanding population. During the Middle Ages and later, a great commerce developed. The nations of Europe rose and fell by their control of the herring fishery of the North Sea. Later, salt cod from Newfoundland and New England became very important.

In addition to preservation, another reason for salting fish was to reduce its weight. Fresh fish are mostly water, and the salting process draws out a good part of it. In fact, salting and drying reduces the overall weight of fish by as much as 80 percent. The volume is also reduced. This fact was important to anyone transporting fish by mule train, sailboat, or dogsled.

Even today, salting the catch will often help with storage and transport problems, since the salt cure requires no refrigeration or ice. But culinary considerations are perhaps more important for modern man. As the recipes in this chapter show, properly prepared salt fish have a unique flavor and have become part of the regional cuisine of some areas. Even the texture of a familiar fish can be altered by a salt cure. Soft fish such as crappie or spot, for example, can be made much firmer. Also, bony fish such as suckers, pickerel, and shad can be salted to advantage; the salt softens the bones, making these fish easier to eat.

There are some rather fierce regional salt-fish favorites, such as salt mullet along the Gulf of Mexico, salt cod along the northeastern seaboard, and salt herring in the North Sea countries, but the techniques for salting the various kinds of fish are pretty much the same from one area to another. There are, of course, a number of recipes for salting fish at home or in camp, and champions of this or that exacting technique will no doubt stand firm, regardless of what I say. But the plain truth is that if you leave the fish in contact with enough salt for a long enough period of time, it’s hard to go wrong from a curing viewpoint.

How much salt? Lots of it. It’s best to buy inexpensive salt by the bag—25-, 50-, or even 100-pound sizes. Almost any salt will do, even that used to de-ice roads and sidewalks.

Salting Techniques

Anyone who has a burning culinary or historical interest in salt fish should read Fish Saving: A History of Fish Processing from Ancient to Modern Times, by C. L. Cutting. In this tome are many salting techniques, mostly of commercial application. Since the advent of mechanical refrigeration and more speedy transportation, the commercial trend has been toward a lighter cure. Also, the cure is often combined with light smoking in modern times.

In spite of a wealth of historical and regional formulas, I feel that the modern practitioner, and certainly the novice, can get by nicely with the simple methods below.

A Basic Salt Cure

Catch lots of good fish, preferably in the 1- to 2-pound range. Low-fat, white-fleshed fish like large crappie, walleye, and black bass are good when salted, and so are the fatty fish like mullet and mackerel. Dressing the fish for salting is easy. Without scaling or skinning, merely cut a slab of fish off each side of the backbone, lengthwise, as when making a fillet cut. Of course, you will cut close to the bone, getting all the meat you can. That’s it. No gutting or beheading. Leave the skin and scales on. Wash the fish in a solution of 1 cup of salt to a gallon of water. Then drain the fish.

Find a wooden, plastic, or other non-metallic container of suitable size and shape. Wooden chests are traditional, but large plastic or Styrofoam ice chests are easy to use at home, in camp, or even in a boat. Put a layer of salt in the bottom. Also place some salt in a separate container such as a plastic dish or tray. Lay each fish on the salt in the tray, turn it, and pick it up by the tail, bringing out as much salt as sticks to it. (Also put some salt into the body cavity if the fish has been dressed in the round.) Place a layer of salted fish, skin side down, atop the salt on the bottom of the chest. Then add another layer of salt, a layer of fish, and so on. Place the last layer of fish skin side up, and cover it well with salt. Lots of salt. Cover the container, and put it in a cool place for a week. (A basement is ideal. I have also put them under the house.) A brine will develop as the salt draws the water out of the flesh. In short, the fish will shrink in size and become firmer.

After a week, remove the fish and discard the brine. Make a new brine by boiling some water and adding salt to it until the solution will float a raw egg. While the new brine is still hot, add a few peppercorns if you want. Cool the brine. Put the fish back into the container and pour the cooled brine over them. A weight of some sort, such as a glass platter or a block of wood, should be put on top so that the fish will not float and be exposed to the air. Never use a metallic weight. Cover the container with a cloth and leave it in a cool, dark place for 2 weeks. The fish can be stored for longer periods in the brine, or they can be removed, washed, packaged, labeled, and frozen until you are ready to use them.

Here’s an interesting cure that provides a method of taking the fish out of the water and putting them into the brine without having to waste time gutting or cleaning them, which makes it a good technique for curing fish that are taken in large numbers. The method is quoted in full from Mary Randolph’s The Virginia Housewife, first published in 1860. The words “brine left of your winter stock for beef” refer, of course, to the brine left over from salt-curing beef; if this sounds just too frugal, remember that salt was harder to come by in those days. Of course, the modern practitioner might prefer to use fresh brine. (If not, see the brine cure on page 342.)

The best method for preserving herrings, and which may be followed with ease, for a small family, is to take the brine left of your winter stock for beef, to the fishing place, and when the seine is hauled, to pick out the largest herrings, and throw them alive into the brine; let them remain twenty-four hours, take them out and lay them on sloping planks, that the brine may drain off; have a tight barrel, put some coarse alum salt at the bottom, then put in a layer of herrings—take care not to bruise them; sprinkle over it alum salt and some saltpeter, then fish, salt, and saltpeter, till the barrel is full; keep a board over it. They should not make brine enough to cover them in a few weeks, you must add some, for they will be rusty if not kept under brine. The proper time to salt them is when they are quite fat: the scales will adhere closely to a lean herring, but will be loose on a fat one—the former is not fit to be eaten. Do not be sparing of salt when you put them up. When they are to be used, take a few out of brine, soak them an hour or two, scale them nicely, pull off the gills, and the only entrail they have will come with them; wash them clean and hang them up to dry. When to be broiled, take half a sheet of white paper, rub it over with butter, put the herring in, double the edges securely, and broil without burning it. The brine the herrings drink before they die has a wonderful effect in preserving their juices: when one or two years old, they are equal to anchovies.

I once salted down a batch of small fish—6- and 7-inch golden shiners—on a wooden plank. The fish were scaled, beheaded, washed, and drained. A layer of salt was sprinkled onto the plank. The fish were dredged in salt, then put down in a single layer without touching. Salt was piled on top, and the board was tilted a little in the deep sink in our laundry room so that the moisture could run off.

After a few days, some of these were freshened and fried. I found them to be quite tasty, and, as I hoped, they could be eaten bones and all. For the sake of gastronomic research, I washed the salt from the remaining shiners, put them back on the board, and placed them under an air-conditioning vent for drying. These were kept for several months without signs of rotting, but finally my wife claimed that they were starting to smell and she wanted them out of her laundry room. Since they were bone-dry by now (and really didn’t smell), I put them into a plastic container and hid them under the counter in the kitchen. She ran across them one day about a year later and said, in gist, that she wanted them out of her house. The fact that the fish were still edible seemed to make no difference to her. Some women are just hard to live with. In any case, dried fish are covered later in this chapter.

After experimenting with the shiners, I used the same wooden-plank method to salt down some mullet fillets and again to salt a few sucker fillets. The method worked nicely, and I recommend it for salting a few small fish or fillets.

Recipes for Salt Fish

Ironically, some of the best recipes for salt fish were developed in West Africa, the West Indies, and eastern South America—far from the codfish banks of Newfoundland and the North Sea. Why? During the world’s colonial period, salt fish was shipped by the ton to these parts from Europe, Newfoundland, and New England. The people developed recipes for cooking the hard salt fish, often with the aid of native ingredients, and developed a taste for them. Even today, in an age of mechanical refrigeration, salt fish are quite popular in many parts of the world. I like them, too, and I remember that my father was fond of eating fried salt fish for breakfast.

Before cooking, most of the salt is removed by soaking the fish overnight in several changes of cool water. This is called freshening. Still, anyone who objects to the salty taste should avoid the fried fish recipes and try those that contain other ingredients—especially potatoes, which absorb some of the salt. In any case, the recipes that follow should contain something for everybody. When serving, remember that salt fish is firm and rich and quite filling, so large portions aren’t required.

One of my favorite salt-fish recipes comes from halfway around the world. In the Indian Ocean, 500 miles east of Madagascar, sits the small island of Mauritius. Over the years, its people developed a superb blend of flavors with salt fish and other ingredients.

1 pound salt fish

¼ cup peanut oil

1 medium onion, chopped

2 cloves garlic, minced

1 tablespoon chopped fresh parsley

6 green onions with tops, chopped

2 cups fresh cherry tomatoes, halved

1 teaspoon finely grated fresh ginger

cooked rice

Wash the salt fish, remove the skin, and flake the meat from the bones in large chunks. Put the fish pieces into a glass or nonmetallic container, cover with water, and soak overnight in the refrigerator. Change the water a time or two if it is convenient to do so.

When you are ready to cook, drain the fish and pat dry. Heat the peanut oil in a large frying pan and sauté the fish chunks for 5 to 6 minutes. Then add the onion, garlic, parsley, chopped green onions, and halved cherry tomatoes to the frying pan with the fish. Heat and stir until the onion is soft. Add the ginger and stir. Cover and simmer for 15 to 20 minutes. Spoon the fish over fluffy rice. This dish is quite rich and will serve 4 people of ordinary appetite.

This technique works for most bony fish, but suckers are my favorite in spite of the bad press they have received over the years. These are salted by the method given in the first part of this chapter. Before salting, however, the suckers are filleted. Each fillet is “gashed” with a sharp knife on a diagonal, placing the cuts about ½ inch apart. Do not cut all the way through the fish, but do cut through the layer of Y-bones. With a little practice, you can feel the bones as you cut.

salt suckers or other bony fish

buttermilk

pepper

fine stone-ground white cornmeal

peanut oil

Soak the salt fish in cool water all day or overnight, changing several times. Scale the fish and soak them in buttermilk for 4 hours. Drain the fish, sprinkle each piece lightly with pepper, and shake them in a bag with cornmeal. Heat at least ½ inch of peanut oil in a frying pan. (Or rig for deep-frying if you prefer.) The oil should be very hot, but not smoking. Fry the fish for a few minutes, until they are nicely brown on each side. Drain each piece well on brown grocery bags or other absorbent paper. Eat while hot.

Here’s a recipe from the Nova Scotia Department of Fisheries. The official version calls for salt cod, but any good salt fish will do.

1 pound salt cod

2 cups mashed potatoes

¼ cup finely chopped onion

¼ cup finely chopped fresh parsley

¼ cup grated cheddar cheese

1 teaspoon black pepper

dry bread crumbs

cooking oil

Freshen the fish by soaking it overnight in cold water. Change the water once or twice if convenient. Simmer the fish in a little water for 10 to 15 minutes, until it flakes easily when tested with a fork. Drain the fish and flake the flesh off the bones. Mix the fish flakes, mashed potatoes, chopped onion, parsley, cheese, and pepper. Form the mixture into patties. Roll each patty in bread crumbs. Heat about ¼ inch of oil in a skillet and fry the cakes for 2 to 3 minutes on each side, or until golden brown. There’s enough here to serve 3 or 4 people.

Variation: For fish balls, add an egg to the mixture and shape it into small balls instead of patties. Deep-fry in very hot oil. Drain well on absorbent paper before serving.

The Scandinavians developed a way of preparing salt fish with sour cream, and several other peoples, especially in the Middle East, cooked salt fish in cream or milk. Here’s my version.

1 pound salt fish, boned and skinless

1 tablespoon butter

¼ cup sour cream

¼ cup chopped onion

1 tablespoon chopped fresh parsley

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

⅛ teaspoon white pepper

Soak the salt fish in fresh water overnight or longer, changing the water several times. Flake or chop the fish and drain it well. Melt the butter in a frying pan and sauté the fish flakes for 6 to 7 minutes over high heat. Drain on brown paper. In a serving bowl, mix fish, sour cream, onion, parsley, lemon juice, and pepper. Serve cold on crackers. Feeds 3 or 4.

Here’s an old recipe that calls for salt herring. Other salt fish can also be used.

2 salt herring

2 large onions, sliced

2 or more cups hot vinegar

2 tablespoons brown sugar

½ teaspoon black pepper

Wash the salt herring. If they are whole, fillet and discard the backbone. Cut the meat into chunks and soak overnight in cool water, changing it a time or two. Drain and rinse the pieces. Layer the fish in a deep bowl, alternating with a layer of onions. Cover with water, then pour the water into a measuring bowl and note the amount. Discard the water and place an equal amount of vinegar into a saucepan, then stir in the brown sugar and black pepper. Bring the vinegar to a light boil, then pour it over the fish. Cover the container, then cool it in the refrigerator for several hours. Serve cold.

In The Country Kitchen, a British cookbook, author Jocasta Innes says that this dish was a favorite in medieval times, when salt cod was a way of life. She says the sweet parsnips balance the salty fish. I agree. The measures in this recipe make up a good batch, and you may want to reduce everything by half.

THE COD

2 pounds salt cod

¾ cup milk

¾ cup water

2 pounds parsnips, peeled and cut into strips

⅓ cup butter

pepper to taste

1 teaspoon ground coriander

Freshen the salt fish in several changes of cold water. Then put the fish into a large pan or stove-top dutch oven and cover with cold water. Bring to a boil, then drain off the water and discard it. Next, cover the fish with a mixture of the milk and ¾ cup water. Add the parsnips. Bring to a boil, reduce the heat to low, cover, and simmer for 45 minutes. Remove the fish carefully and place it in a slow oven to dry. Strain out the parsnips, being sure to retain the stock. Mash the parsnips with a potato masher, adding the butter, pepper, and coriander as you go. Stir in a little of the reserved stock until the parsnips are creamy. Serve the fish and mashed parsnips separately, along with the following egg sauce.

THE SAUCE

¼ cup butter

1 tablespoon flour

3 chicken egg yolks, well beaten

2 cups reserved fish stock

Melt the butter in a saucepan. Stir in the flour and then the egg yolks. Slowly add fish stock. Stir until the sauce is thick, then turn off the heat and let the sauce rest for a while. Serve the sauce hot over the fish.

My father was fond of eating salt fish for breakfast, and I, too, like them after nine o’clock, along with fresh sliced tomatoes. In rural Florida, it is traditional to serve this with grits. Exact measures aren’t specified, but I like to have about half egg and half fish by volume.

salt fish, flaked

chicken eggs

green onions, finely chopped

butter

black pepper

toast

vine-ripened tomatoes

Soak the fish in water overnight, changing the water a time or two. When you’re ready to cook, drain the fish, bone the meat, chop it, and mix it with the eggs in a bowl. Stir in a little green onion, including part of the tops. Melt some butter in a frying pan. Scramble the egg-andfish mixture until done. Add pepper to taste. Serve hot with toast and slices of homegrown tomatoes.

International Salt-Fish Specialties

A surprising number of specialty dishes, from Swedish gravlax to Indian Bombay duck, are made with salt fish. Some of these—mostly appetizers—are eaten without being cooked. On first thought, this fact may turn you off from these delicacies, but remember that caviar is not cooked either. I enjoy most of these dishes very much, but I want to make my own, starting with very fresh fish.

In Iceland and Sweden, Atlantic salmon are salted and eaten with a mustard dill sauce. I highly recommend the method for coho or any fresh salmon that you have caught yourself, or that you are certain are very fresh. (This recipe calls for a light salt treatment, which in my opinion should be used only with very fresh fish.) Some books recommend that you use salmon steaks, but boneless fillets work much better. Note also that the name for this delicacy is sometimes spelled gravad lax.

boneless fillets from a 5- to 6-pound salmon

3 tablespoons coarse sea salt

2 tablespoons sugar

2 teaspoons freshly ground black pepper

2 teaspoons crushed dried juniper berries

fresh dill

Pat the salmon fillets dry with a paper towel and place them, skin side down, on an unpainted board about 6 inches wide and long enough for the fish. (Cut two such boards and save one for the top.) Mix the salt, sugar, pepper, and juniper berries; sprinkle the mixture over the salmon fillets evenly from one end to the other. Place a few sprigs of dill over half of the fillets, then put the other fillets on top with the skin side up. (In other words, put the salmon halves back together, sandwiching the salt and dill sprigs.) Wrap and overlap the fillets first with wide plastic wrap and then with wide freezer paper. You’ll need to seal the fish, remembering that it will be turned over a few times while curing.

Put a plank over the fish and press down on it a little, more or less seating the boards. Then weight the top board with several cans of vegetables (or some other suitable weight of about 5 pounds). Put the whole works in the refrigerator for at least 2 days, turning the planks and fish every 12 hours or so. Do not unwrap the fish; the idea is to contain the liquid in the package. The salmon should be eaten within 4 days.

To serve the gravlax, remove it from the wrap, drain it, and pat it dry. Put it skin side down and, with a thin, sharp knife, slice it crosswise into thin slices—no more than ⅛ inch thick. Cut down to the skin, then cut the slice away from the skin. This is easy once you get the hang of it. Keeping the salmon cold will make it easier to slice. Serve the salmon slices on a plate with the mustard dill sauce and fresh pumpernickel. Here’s what you’ll need for the sauce:

¼ cup Dijon or German prepared mustard

1 tablespoon sugar

½ teaspoon ground white pepper

3 tablespoons olive oil

2 tablespoons white wine vinegar

salt to taste

¼ cup minced fresh dill

Thoroughly mix the mustard, sugar, and pepper in a bowl with a whisk. Continue to whisk while adding a little oil in a thin stream. Stop. Whisk in 1 teaspoon of wine vinegar. Whisk, add more oil, whisk, and so on until the oil and vinegar have been used up. Stir in the salt to taste, then stir in the dill. Transfer the sauce to a serving bowl and refrigerate it until you are ready to eat. The sauce will keep for a few days, but it will need to be fluffed up with a whisk before serving. The same sauce can be used with the following recipe.

This Norwegian dish usually is made these days with farmed rainbow trout. Traditionally, the trout are processed in a wooden container that will hold about 4 gallons, but I have found a Styrofoam ice chest to be satisfactory.

Catch some trout of about 1 pound each and fillet them. In the bottom of the container, put a layer of coarse salt at least 2 inches deep. (You may want to use rock salt for this purpose because sea salt is so expensive these days.) Add a layer of trout, skin side up. Do not overlap the trout. Add a thin layer of salt, covering all the fish but not piling it on. Add another layer of trout, and so on, until you fill the box or run out of fish. Top with salt.

This dish is usually made in the fall, when the weather is cool, and the Norwegians merely sit the box outside in the sun for 3 to 4 weeks. If you live in a hot climate, turn the air conditioner down to 70°F and set the box in a picture window that catches the morning sun. Be warned that this stuff smells almost as loudly as batarekh (page 279), so keep the lid on tightly if your spouse is hard to live with.

Serve the trout (without cooking it) with thin bread and a little hot prepared mustard. If you have prepared a whole box of these trout only to find that you don’t like them, or they are too strong or too salty for your taste, soak them in milk overnight to soften and sweeten them. Then dust them with flour and fry ’em in butter. Or flake off the meat and use it to make salt codfish balls, using any good New England recipe. In Boston, according to my copy of the Old-Time New England Cookbook, salt codfish balls, Boston brown bread, and Boston baked beans are traditionally served up for breakfast on Sunday morning. (Really good Boston baked beans, I might add, are always cooked in a cast-iron pot with a slab of salt pork.)

If we may believe the critics (and I have no reason to disagree), the best caviar is made from the roe of various sturgeons. Usually, expensive caviar is made from roe with large berries. Part of the gustatory sensation occurs when these berries pop, releasing a burst of flavor. Although caviar can be made from good roe from most fish, such as salmon and carp, I suggest that roe with small berries (or grains) be made into another delicacy, as described in this recipe, or be used for pressed caviar instead. Like wine making, the processing of caviar can be as complicated and as highly technical as you choose to make it. For openers, try the simple recipe below.

2 cups very fresh roe with large berries

4 cups very good water

1 cup sea salt

Keep the roe on ice until you are ready to proceed—preferably very soon after catching the fish. Find some nylon netting with the mesh a tad larger than the berries. (Netcraft and some mail-order houses carry netting.) Boil the netting to sterilize it, then stretch it over a clean nonmetallic bowl. Break the roe sacs and dump the berries onto the netting, carefully helping them along, and gently rub them about so that the berries drop through the netting. The idea is to separate the eggs from the membrane without breaking the eggs open.

When you have separated the eggs, mix the water and salt, then pour the brine into the bowl over the eggs. Stir gently with a clean wooden spoon, and with your free hand remove any membrane that rises to the top. After 20 minutes, scoop out the berries and place them in a strainer (preferably made of plastic) over another bowl. Put the strainer and its bowl into the refrigerator to drain for an hour or so.

Have ready a sterilized 2-cup jar (or several jars if you have landed a sturgeon). Using a sterilized wooden spoon, put the berries into the jar. The jar should be as full as possible to minimize the amount of air, but the berries should not be broken by packing too tightly. Cap the jar with an airtight lid, then store the caviar in the refrigerator. Note that caviar made by this method is not really cured and should be eaten within 3 to 4 weeks.

I like caviar on thin crackers with a little cheese, but more sophisticated folks have other ideas. In any case, this caviar can also be used in most recipes that call for caviar.

Old salts in Florida and along the Atlantic Coast will be surprised to learn that salt-dried mullet roe was enjoyed by the ancient Egyptians. Ready-made batarekh is still marketed in Egypt, and possibly in some Paris outlets, where it is called boutargue or (I think) bottarga. European or Egyptian gourmets might argue for the roe of the gray mullet seined from the Mediterranean or perhaps caught with a hook baited with cooked macaroni, but the weathered folks along the Outer Banks of North Carolina will tell you that the roe of their coastal mullet is the best in the world—far surpassing the golden berries of even the rare sterlet sturgeon. Old crackers on Florida’s Gulf Coast will champion their own mullet, some of which are a little different from those that run the Atlantic Coast. Once, I could buy fresh mullet roe and milt from my local fish markets, but in recent years, Japan and Taiwan have hogged the market for the sushi trade. They buy the roe by the ton, salt it, dry it, change the name to karasumi, and sell it back to us at $70 an ounce, or thereabouts. They also make a similar product, tarako, from salt-cured Pacific pollack.

In any case, the roe of cod is also excellent and can be used in this recipe. Menhaden, American shad, hickory shad, mooneye, and other good herring also yield excellent roe. My favorite batarekh, however, is made from the roe of bluegills, which is readily available to most Americans. Most of the farm ponds in this country are overstocked with bluegills, and these are fat with roe in summer. Catch some and try batarekh. True, it’s an acquired taste, but before long you’ll crave more—especially if you have been on a no-salt diet.

Start by carefully removing the roe from the fish, being careful not to puncture or divide the two sacs. Wash the sacs and dry them with a paper towel or soft cloth. Place them on a brown grocery bag and sprinkle them heavily with sea salt. (Ordinary table salt can be used, but sea salt has more minerals and more flavor.) Put the bag in a cool place. After about 2 hours, the salt will have drawn some of the moisture out of the roe and the brown bags will be wet in spots. Put the roe sacs on a new brown bag and sprinkle them again with salt. Change the bag after about 3 hours and resalt the roe. Then wait 4 to 5 hours. Repeat until the roe is dry and leaves no moisture on the bag, at which time it will be ready to eat. This will take about 3 days, but after the first 8 hours or so the bag won’t have to be changed very often. Small roe won’t take 3 days, however, to dry sufficiently. Be warned that batarekh smells up the house, so it is best to make it on the screened porch or in a well-ventilated place. After it is cured sufficiently, it can be stored for a while in the refrigerator, but it’s best to wrap each roe sac separately in plastic wrap. For longer storage, dip each roe sac in melted paraffin.

Beginners should eat batarekh in thin slices with a drop of lemon juice and a thin little cracker or buttered toast. After the first 2 or 3 slices, omit the lemon and cut the slices a little thicker. Being salty, batarekh goes down nicely with cold beer. Don’t throw out your batch of batarekh if it doesn’t hit the spot, or if you’ve got squeamish guests scheduled for dinner or cocktails. (As I’ve often pointed out, one of my sons won’t touch batarekh, pharaohs notwithstanding, because, he says, it looks like little mummies.) I like to use grated batarekh as a seasoning and topping for pastas and salads—and it really kicks up an ordinary supermarket pizza. Just grate some on the pizza atop the regular toppings. (I prefer pizza supreme with a little of everything.) Sprinkle shredded cheese over the batarekh and broil until the cheese begins to brown around the edges and the pizza is heated through. Have plenty of good red wine at hand if you are feeding bibulous guests.

This pizza is one of my favorite quick foods. The grated batarekh can, of course, also be used to advantage in pizza made from scratch if you are a purist.

Also, I find that grated batarekh can really pick up a piece of cheese toast for a quick snack. Here are some other ways to use batarekh—gourmet fare without the mummy image.

This dish, popular in both Greece and Turkey, is often made these days with smoked cod roe. The original, however, calls for salt-dried roe of the mullet. It’s made from tarama, which is similar to batarekh (page 279) except that the roe is pressed. (The Russians also eat bricks of highly salted and pressed caviar that could be used in this recipe.) Most people won’t know the difference.

3 ounces batarekh

4 slices white bread

1 cup milk

1 clove garlic, crushed

juice of 1 lemon

¼ cup olive oil

Greek black olives

Crush the batarekh in a mortar and pestle until it has a smooth texture. Remove the crust from the bread and soak the bread in milk. Squeeze out the milk, then mix the bread into the batarekh, along with the garlic. Grind this mixture with the mortar and pestle until the mixture is smooth. Slowly stir in the lemon juice and then the olive oil, tasting as you go. Add more lemon or more garlic if needed to suit your taste. Serve with thin toast or crackers, along with the black olives. I like a little white feta cheese on the side.

According to Claudia Roden’s A Book of Middle Eastern Food, fessih is a fish that has been salted and buried in the hot sand to ripen. When ready, it will be soft and salty. Ms. Roden allows that people in the West may want to use anchovy fillets in lieu of fessih. (Use canned anchovies, or make your own “anchovies”; see below.) Also, the recipe requires some tahini, a paste made of sesame seeds.

½ cup tahini

½ cup fresh lemon juice

1 large mild onion, sliced

2 cloves garlic, crushed

salt to taste

½ teaspoon ground cumin

2 (2-ounce) cans anchovy fillets

1 large, ripe tomato, thinly sliced

pita bread

chopped fresh parsley

Put the tahini, lemon juice, onion, garlic, salt, and cumin in a blender or food processor. Zap it until you have a smooth paste, adding a little water if needed. Purists will want to adjust the amount of lemon juice, salt, and cumin until they have an exact flavor and texture. Mince the anchovies and stir them into the tahini cream. Serve in a bowl with large, thin slices of tomato and pita bread. Garnish with parsley.

If you’ve got real anchovies, you’re in business. Also, finger fish such as smelts, shiners, and sand lances will do. If the fish are 4 inches or less, behead and gut them. If they are larger, fillet them. Even small bluegills can be used if they are filleted and perhaps cut into strips to resemble canned anchovies.

Clean and wash the fish according to size. Pat the fish dry. Sterilize some jars with canning lids. Cover the bottom of each jar with a little salt. Add a layer of fish, sprinkling the body cavity of each one with salt as you go. Add a layer of salt, a layer of fish, and so on, packing lightly as you go and ending with a layer of salt. A top space of about ½ inch should be left in each jar. Weight the anchovies with a slightly smaller jar (or other suitable nonmetallic container) that has been filled with water. Put the packed jar (with the weighted jar in place) in a cool place for a week or so. When ready, remove the weighted jar or container. By now, a brine will completely cover the fish. (Fatty fish such as echelon may develop a layer of oil on the surface. Skim this off if you choose.) Seal the jars and store them in the refrigerator. They will keep for a year or longer.

Before serving these in Greek salads and other raw dishes that call for canned anchovies, I like to remove the fish from the brine, rinse them, pat them dry, and dip them in olive oil. Note that the salt will have softened the small bones in the fillets. Whole fish should be boned, which is easily accomplished by spreading the body cavity, pulling off one side, and lifting out the backbone.

According to George Leonard Herter, the late Clarence Birdseye, the father of frozen supermarket foods, came up with the following recipe for salmon and other fatty fish such as bullheads. Further (Herter says), the same dish was once called salmon fuma in New York City.

1 gallon water

2½ cups salt

1⁄6 ounce sodium nitrate

1⁄32 ounce sodium nitrite

5 teaspoons liquid smoke

3 pounds skinless fresh salmon fillets

Pour the gallon of water into a crock or other large nonmetallic container. Dissolve the salt in the water, along with the sodium nitrate and sodium nitrite. See whether a chicken egg will float in the solution. If not, add more salt until the egg rises. Then stir in the liquid smoke. Put the fillets into the solution and weight with a plate or some nonmetallic object of suitable size; the idea is to keep the fish fillets completely submerged at all times. Leave the fish in the solution for 4 days. (If you feel compelled to stir the fish a time or two, use a wooden spoon.)

Drain the fish. Before serving, slice the fillets into very thin slices. Partially freezing the fillets and slicing with a sharp, thin knife will help. Serve atop crackers.

Air-Dried Fish

Although air-dried fish—one of man’s first preserved foods—is very important from a historical viewpoint, the method has not been popular in America in recent history and has not been widely practiced except by some native peoples in Alaska and Canada. Fish has often been dried for use as food for sled dogs, partly because drying reduces the weight by about 80 percent. In parts of Africa and no doubt other places, fish were dried with the aid of smoke. The smoke helped keep the blowflies away from the fresh fish, and was sometimes discontinued after a day or two.

Stockfish

In the recent past, very large quantities of dried fish were produced commercially in Scandinavia and Iceland, where the dry air and cool breeze made the process feasible on a large scale. Air-dried cod—called stockfish, from the Norwegian stokkfisk or Swedish torrfisk —provided the people of the Middle Ages with food and was later shipped in large quantities to parts of Africa, where dried fish were preferred to salt fish (and still are in some places). Although refrigeration has hurt the stockfish trade, tons of cod are still air-dried commercially in Scandinavia each fall; Norway alone exports 50 million to 55 million pounds of stockfish to Africa in a year, according to The Encyclopedia of Fish Cookery, by A. J. McClane.

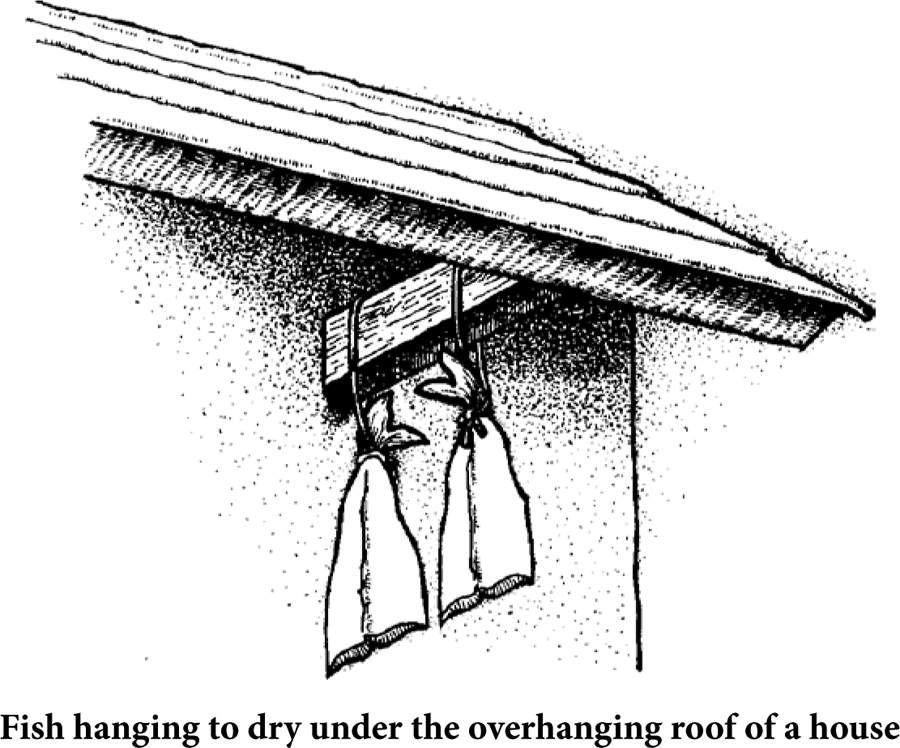

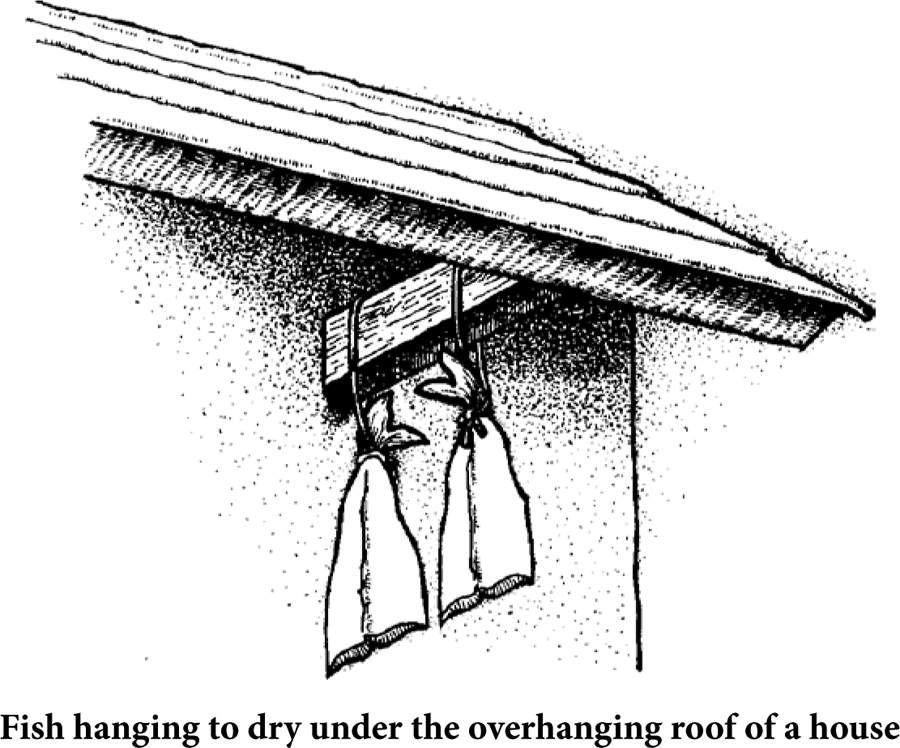

Typically, those cod destined to be stockfish are merely gutted and hung out to dry on huge wooden racks. Of course, a few fish can be dried for home consumption without large racks; often, the gutted fish are hung under the eaves of the house. The drying will take from 2 to 6 weeks, or even longer, depending on the weather and the size of the fish.

The dried fish become very hard, and they require lengthy soaking in fresh water before they become suitable for human consumption. A medieval recipe calls for boiling dried fish in ale, then shredding them and mixing in chopped dates, pears, and almonds. The mixture is reduced to a paste in a mortar and pestle, then shaped into patties, dusted with flour, dipped in a batter, and fried in hot oil.

Modern practitioners may prefer the following recipe.

Several weeks before Christmas, the dried fish are put into a solution of 1 gallon of water and 1 tablespoon of lye; then they are soaked for 2 weeks. For the next week, the fish are soaked in fresh water, changed daily, to leach out the lye. Then the fish are poached gently until the meat flakes easily. The flaked meat is put into a white cream sauce seasoned only with freshly ground black pepper, and served with boiled potatoes.

Racking

Racking is used to dry rather large fish with a low fat content, such as cod, hake, or even flounder. The fish are cut in half, then the backbone, rib bones, and head are removed, leaving the collarbone intact. The sides of the fish are cut into long strips about 1 inch wide; these are left joined together at the collarbone. After being washed, the fish are soaked for an hour in a saturated salt brine (that is, a brine with enough salt to float an egg). They are then hung by the collarbone in a dry place, out of direct sunlight. Drying takes from 1 to 2 weeks, after which the fish can be stored for future use.

The dried fish are soaked in fresh water to freshen the flesh, then creamed or flaked and used in recipes for chowders, fish loafs, or fish cakes. At one time, the dried strips were eaten without cooking, like jerky.

According to A. J. McClane’s The Encyclopedia of Fish Cookery, a major shark fishery exists in Mexico’s Sea of Cortés. In fact, the industry is centered on Isla Tiburón, or Shark Island. The sharks include the mako, brown, blacktip, hammerhead, tiger, bull, leopard, nurse, thresher, and horn. After processing, most of the meat, McClane says, is sold in Mexican markets as salt cod. The fins are dried and sold for Chinese shark-fin soup. The back meat is cut into fillets and soaked for 20 hours in a weak brine of 4 pounds of salt to 10 gallons of water. This soaking leaches out the uremic acid, which is present in most sharks and which gives the meat a strong smell of ammonia.

After brining, the shark fillets are dried in the sun. McClane says that careful drying is critical in preservation, and that the fillets must be evenly exposed to the sun on both sides and protected from damp night air.

For this method of drying shrimp, I am indebted to Frank G. Ashbrook, author of Butchering, Processing and Preservation of Meat. Although shrimp of any size can be dried, the smaller ones work best and are less desirable for the market or other methods of home use. People who have tried to peel enough tiny shrimp to stay ahead of their appetite will see the advantage!

For best results, start with very fresh shrimp. Wash these and bring to a quick boil in salted water, using 1 cup per ½ gallon of water. (Do not try to boil too many shrimp at the same time because they will lower the temperature of the water.) Boil the shrimp for 5 to 10 minutes, depending on size. Drain the shrimp and spread them in the sun to dry. If bugs are a problem, rig a way to cover the shrimp with a fine-meshed screen. The shrimp can be rather crowded but should not form a layer more than 1 inch deep.

For the first day, the shrimp should be turned every half hour. At night or during a rain, remove them to a dry, well-ventilated place; do not merely cover the shrimp with a tarpaulin or other direct covering. If you are really into drying, it’s best to build movable trays with wire or slat bottoms; then the whole tray can be taken inside at night or during a rain. In most areas, you’ll also need a screen cover to keep the flies off the shrimp, or perhaps to keep the seagulls away.

Drying small shrimp will require 3 days in sunny weather, longer if the days are short of sun and wind. When the shrimp are dry and hard, place them in a cloth sack. Beat the sack with a board; this will break the shells. Then winnow the shrimp in a sifting box, made with a wooden frame and ¼-inch mesh. The bits of shell will fall through, leaving the dry shrimp meat on top. This will be much smaller and lighter than the original. In fact, 100 pounds of shrimp will shrink down to 12 pounds of meat. The dried shrimp can be put into jars and stored in a dry place.

The dried shrimp can be used in soups and stews that will be cooked for some time, or they can be freshened by soaking in water for several hours. Freshened shrimp can be dusted with flour and fried or sautéed in butter, or they can be eaten raw as appetizers.

Asian and regional Mexican cuisines make good use of dried shrimp, which can be purchased in some ethnic markets. Usually, the shrimp are dried with the aid of salt. In addition to shrimp, the Chinese also dry and market oysters, squid, sea cucumbers, and even jellyfish. Scallops are sometimes air-dried.

Here’s a technique that I like to use for quick-drying 2 to 3 pounds of shrimp. Peel and devein the shrimp, place them in a shallow tray, and cover them with a cure made with 1 pound salt, 2 cups brown sugar, 1 tablespoon onion powder, and 1 teaspoon ground allspice. Place the tray in the refrigerator for 6 to 8 hours.

Wash the salt cure off the shrimp and pat them dry with paper towels. Place the shrimp on cookie sheets and dry in the oven for about 12 hours on low heat; use the lowest setting on your oven, and leave the door ajar. After drying the shrimp, pack them into airtight containers and refrigerate them for up to 3 months, or freeze them for longer storage. Use the shrimp in soups and stews, or in any Asian recipe that calls for dried shrimp.

One purpose of adding lots of salt to fish is that it draws out the moisture, thereby speeding up the drying and curing processes. Usually, small fish to be salt-dried are gutted and beheaded; larger ones are filleted, leaving the collarbone intact to help hold the fish together while hanging.

After dressing, the fish are usually washed in salted water, made by adding 1 cup of salt to each gallon of water. The fish are drained, then dredged in a box of salt. Another box is lined on the bottom with salt, and the dredged fish are put down in a layer. Salt is scattered over the layer, then another layer of fish is put down, and so on. As a rule, the total amount of salt used in this process is 1 pound per 4 pounds of fish. Using too much salt will “burn,” or discolor, the fish.

The fish are left in the salt for at least a day, or up to a week, depending on the size of the fish and the weather. Then the fish are rinsed and scrubbed to remove the brine. Next, they are drained for a few minutes and hung on racks or placed on drying trays. They are usually kept in a shady place with a good breeze.