Be warned once again that salt, not smoke, is the curative agent in cold-smoked fish. In addition to inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria, the salt draws out moisture—and moisture is necessary for bacteria to thrive. How much salt and for how long depends on the size of the fish and other factors, and how long the fish is to be preserved. As a rule, the more salt, the drier the fish and the longer its shelf life. In modern times, the trend has been toward less and less salt combined with refrigerated storage, and this chapter tends to reflect this change. (If you want completely cured smoked fish, begin with a hard salt cure as described in chapter 2, Cured Fish, page 267, and cold-smoke the fish in the smokehouse for a week or longer.) The trouble with a light cure/light smoke approach is that the practitioner has no hard and fast rules to follow. In any case, I can only hope that I can shed enough light on the subject to keep the novice from proceeding in the dark.

Dressing and Hanging the Fish

It’s best to start with very fresh fish. If you catch your own, gut and ice them as soon as possible. Better, gut them and put them into a slush of ice and brine; this will start the salting process right away. Before gutting and cleaning the fish, however, consider how they will be handled for salting, drying, and smoking.

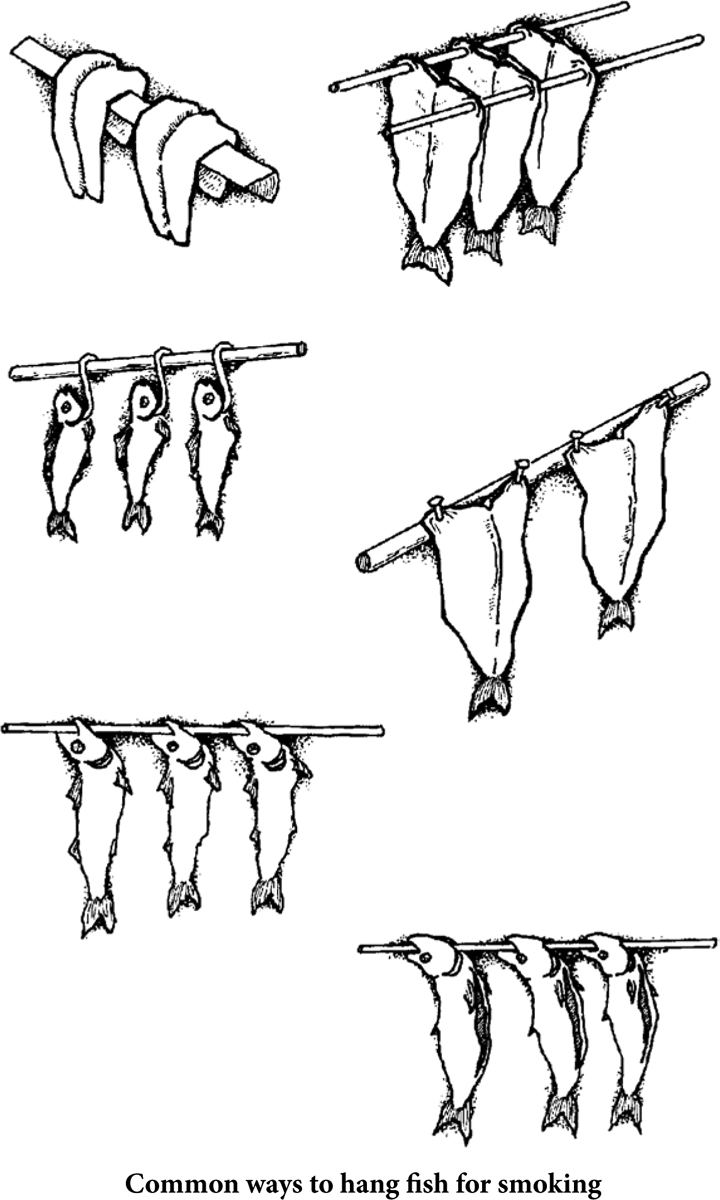

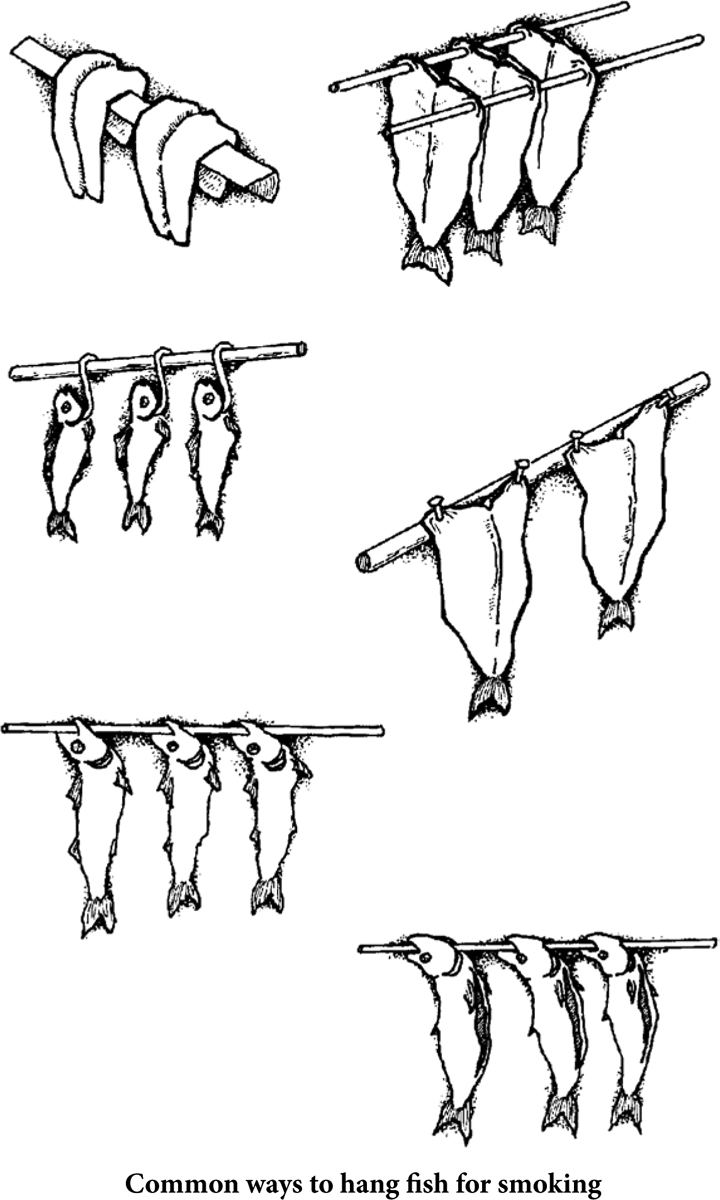

Fish to be smoked can be suspended vertically in several ways. They can also be placed horizontally on a rack. How they are to be hung depends partly on practical considerations, such as your facilities and the size of the fish. Here are some basic techniques to consider.

Gibbing

This is a method of dressing small fish without slitting the belly open. Instead, a small cut is made across the bottom of the fish, close to and behind the gills. The gills and innards are pulled out and the body cavity is washed thoroughly with cold water. (A hose with an adjustable, pistol-grip nozzle helps do a good job.) After gibbing, the fish can be hung on a rod, running it through the mouth and out the gill, or vice versa. They can also be hung by pushing the rod through the eye sockets. In either method, it’s best to leave a little space between the fish.

Gutting

Small whole fish are usually dressed by cutting a slit in the belly and removing the innards. I prefer this method to gibbing. Gutting may or may not take a little longer, depending on how thoroughly you want to wash out the cavity. The fish can be hung by the methods described under gibbing.

Butterflying

This method of dressing a fish leaves the two halves hinged at the belly. First, the fish is beheaded. During beheading, the collarbone is left in if the fish is to be hung; it can be removed if the fish is to be placed on a rack. After beheading, the fish is cut from the head to the tail from the top. Cut as close as possible to the backbone and through the rib cage. (With large fish, you may prefer to work the knife around the rib cage, leaving the ribs attached to the backbone.) It is important that the knife not cut all the way through the belly flesh. Turn the fish and cut it in a similar manner on the other side. Next, the backbone and tail can be lifted out, along with the innards. Finally the fish is opened like a butterfly. It can be hung or placed on racks.

Filleting

Large fish should be filleted for both curing and smoking. In most cases, a slab of fish is cut off either side of the backbone. Of course, the process should waste as little meat as possible. In my opinion, it’s best to start the cut from the tail, then cut through the ribs as you approach the head; this will leave the rib bones intact. For completely boneless fillets, you can cut out the rib section or remove the bones one at the time. There are other methods of filleting, and some people may prefer to work the knife in at the head and toward the tail. In either case, leaving the skin on the fillet will help hold it together during curing, smoking, and handling.

For smoking, fillets are usually placed skin side down on suitable racks. They can also be draped across a rod, skin down.

Tailing

Small whole fish, such as smelts, can be gibbed or gutted and tied at the tail in pairs. These can be hung over rods for smoking. One pair should not be allowed to touch another.

The Salt Cure

As a rule, it’s best to dry-cure fish with a low fat content, such as cod, and brine-cure fish with a high fat content, such as mackerel. But the methods are usually interchangeable, especially if you are after a rather light cure to be followed by refrigeration or freezing. Unfortunately, there are infinite variations on the basic methods of salt-curing fish in preparation for smoking; instead of rhyme and reason, we have purely personal and regional variations, which are often staunchly defended. I’ll try to keep it simple.

Although many ingredients are sometimes used in the cure to flavor or preserve the fish, most of these are not necessary and may be counterproductive. I do, however, insist on either brown sugar in a dry cure or molasses in a brine cure. The sugar or molasses helps the color as well as the flavor of smoked fish. The measures can be increased or decreased proportionally. Note that these proportions yield a relatively weak brine, as fresh water will dissolve well over 2 pounds of salt per gallon. Note also that water is a major ingredient in the brine cure and should have a good, clean, fresh taste. Distilled water isn’t usually necessary, but some water tastes of natural elements, such as sulfur, and sometimes of added chemicals, such as chlorine. If in doubt, use distilled water or perhaps bottled mineral water. Water from a good spring is hard to beat.

1 pound salt

1 gallon good water

1 cup dark molasses

Dress the fish and place them in a nonmetallic container, then cover with the brine, following the proportions above. Place a plank or plate over the fish and weight it with a bowl, stone, or some such nonmetallic object. The idea is to completely submerge the fish. Leave the fish in the brine for 12 hours or longer. (For a hard cure, more time is recommended, as was discussed in chapter 2, Cured Fish, page 267.) Remove the fish from the brine, but do not wash. Dry the fish and smoke them, as described later in the chapter.

The dry cure should be started by first soaking the dressed fish in a light brine made with 1 cup salt dissolved in 1 gallon water for a period of about 1 hour. (You can actually start this initial brining as you dress the fish, timing the process after dropping in the last one; if I have a choice, I dress the larger fish first simply because they should have more time in the brine.) After soaking the fish, drain them but do not fully dry them. Have a dry cure ready, using the following 8-to-1 formula:

8 pounds salt

1 pound dark brown sugar

Mix the salt and sugar. Place part of this cure (about ½ inch) into the bottom of a curing box, then put the rest into a handy container. Place each fish in the cure, coating both sides, and pick it up with as much cure as will adhere to it. Place the fish on top of the layer of cure in the box. Layer the fish if necessary, sprinkling extra cure between each layer. Leave the fish in the curing box for about 12 hours, or longer for whole fish that weigh more than 1 pound.

Wash the salt cure off of the fish, and then dry the fish as described next.

Forming a Pellicle

After the fish are treated with either a brine or a salt cure, they should be washed and dried before putting them into the smoker. The drying helps in a number of ways, but basically it forms a pellicle, or glazed film, on the surface. This film helps give the fish a better and a more uniform color, and it may also aid in preservation.

After washing the salt from each fish, pat each one dry with paper towels and place it on a rack (or hang it) in a cool, breezy place. If you don’t have a natural breeze, a fan will help. Usually the pellicle will form within 3 hours or less, depending on the size of the fish. After the pellicle forms, proceed with the cold-smoking operation.

Cold-Smoking

The first requirement for cold-smoking is to keep the temperature in the smokehouse or smoke chamber cool. Usually, this requires having the fish a good distance from the fire or source of heat, as discussed in chapter 5, Smokehouses and Rigs (page 318) and chapter 6, Woods and Fuels for Smoking (page 332). It’s best to keep the temperature below 90°F, and certainly below 100°F. I consider 70°F to 80°F ideal.

If the salt cure was sufficient to be on the safe side, you can cold-smoke the fish for a few hours, a few days, or a few weeks. As a general rule, the longer the fish is smoked, the more smoky the flavor; but at some point, the law of diminishing returns sets in and the smoking, if done in a dry atmosphere, becomes more of a drying period than a flavor-enhancing period.

For the modern practitioner, I recommend that the fish be smoked until the surface of the flesh is a good mahogany color and the texture is firm but still pliable to the touch. Drying out the fish is unnecessary if you are going to cook them right away. They can be refrigerated for a week or so, or wrapped and frozen for several months. If you do dry the fish, remember that they should be freshened overnight in cool water before they are cooked.

It is best (but not necessary) to start cold-smoking fish with a light or moderate smoke, then increase the density. It’s also best to keep the smoke coming continuously, but all is not lost if your fire goes out for an hour or so or the fuel gets low in a chip pan over electric heat. Merely resume smoking as soon as you can.

How long should the fish be smoked? A day or two with whole fish of about 1 pound will be about right, but this statement has to be qualified with a bunch of “ifs,” “ands,” and “buts.” The real concern in my conscience is that the fish not be salt-cured properly and then be exposed to a temperature high enough to promote rapid growth of harmful bacteria (higher than 80°F)—but not high enough to cook or retard the bacteria (140°F). Again, beware the gray zone.

How long? If the fish is to be cooked right away, they should be smoked at least long enough to give them flavor—at least several hours, preferably 12 hours or longer for whole fish of 1 pound or more. If the fish are to be preserved for 2 weeks, they should be properly salt-cured and smoked for at least 24 hours; 4 weeks, 48 hours. If the fish are to be preserved indefinitely, they should receive a heavy salt cure and be smoked for several weeks.

In short, if you first salt-cure your fish, cold-smoking is easy if you have a suitable smoke-house. It may be hard to duplicate a particularly good batch exactly (unless you measure all the variables scientifically and keep meticulous notes), but this isn’t an overriding concern unless you are smoking fish commercially.

My best advice is to salt-cure your fish, then cold-smoke more or less at your convenience, give or take an hour or two either way, until the fish have a good color and texture. Then either cook the fish right away, refrigerate them for several days, or freeze them for several weeks. Simple enough? If not, you may want to follow the more specific recipes below, some of which reflect the philosophy of smoking mainly to add flavor instead of preservation.

Modern Cold-Smoking Methods

Although thoroughly cured fish are normally smoked for a long period of time, partly to dry the flesh, you can cut back on the time if the product is to be cooked right away. The shelf life of partially smoked fish can be extended by refrigeration or by freezing. Here are some suggestions for cutting back on the salt or on the smoke, or both.

This salmon method calls for a relatively short cure and short smoking time. After smoking, the fish should be cooked by some method of your choice, or used in the recipes set forth later in this chapter.

1 very fresh salmon, about 10 pounds

2 cups Morton Tender Quick cure mix

1 cup light brown sugar

1 gallon good water

Fillet the salmon and rinse it. Mix the Tender Quick and brown sugar into the water. Put the salmon fillets into a nonmetallic container and cover them with the curing mixture. Place a plate on top so that the salmon fillets are completely submerged, then place the container in the refrigerator for about 24 hours. Remove the salmon fillets and air-dry them. Then arrange the fillets on your smoker racks, skin side down, or drape them over a cross beam, skin side down. (Do not attempt to hang the fillets by the end. If you use the rack in a small smoker, you may have to cut the fillets in half.) Cold-smoke for 24 hours or so.

Then cook the salmon as described below, or use a recipe such as kedgeree (page 350). I like to freeze one fillet for later use, and steam the other fillet for 15 to 20 minutes, or until it flakes easily when tested with a fork. To steam the fillet, cut it in half and place it on a plate, skin side down. Put the plate in a steamer for 15 minutes, or until it flakes easily when tested with a fork. Serve the steamed salmon, skin side down, with rice and vegetables of your choice.

To bake the smoked salmon fillets, simply put them skin side down on a suitable flat cookie pan and bake in a preheated 300°F oven for 25 minutes, or until they flake easily when tested with a fork. Baste once or twice with butter or bacon drippings while baking. Do not overcook.

Cold-Smoked Shrimp

Here’s a method for cold-smoking precooked shrimp. It will add flavor, but the shrimp should be refrigerated after smoking and should be eaten within a week. For best results, you’ll need a large pot that won’t crowd the shrimp during boiling. Add some salt—about 1 cup per gallon. Remove the heads of the shrimp and devein them, but leave the tails on. Bring the water to a boil, add the shrimp, bring back to a boil, and cook for 3 minutes for medium shrimp. (Large shrimp require another minute; smaller shrimp, less time. The shrimp are ready when they turn pink.) Drain the shrimp and arrange them on racks. Cold-smoke for 30 to 60 minutes, depending on size. Eat the smoked shrimp cold, or put them into shrimp salad or other dishes. I like a few chopped shrimp scrambled with chicken eggs and a spring onion or two chopped with half the green tops.

Note: Many people add all manner of Cajun spices and court bouillon vegetables to a shrimp boil. I think that plain salt or sea salt is better, but suit yourself.

Smoked Oysters

Freshly shucked oysters can be smoked successfully, but I really can’t recommend the preshucked “bucket oysters” for sale in supermarkets. Most of these have been washed, or otherwise lack the flavor of their natural juices. An oyster should never be washed, George Leonard Herter notwithstanding, even if it is to be cooked in a stew.

For smoking oysters, you’ll need fine-meshed racks so that they won’t fall through. Grease the racks and build up a head of smoke. Shuck the oysters and place them on the racks without touching them. (Any oyster that is not alive should be thrown out. Also throw out any oyster that has opened, and any oyster that seems a little dry as compared to the others.) Smoke the oysters for 1 hour, or until they have taken on a nice golden color. Place the smoked oysters in a container and coat them with olive oil. Refrigerate and eat within a few days.

If you are squeamish about eating raw oysters, try steaming them on a grill over a hot fire until they pop open. Then shuck them and smoke for 30 or 40 minutes.

Early in the morning, catch some good fish of about 2 pounds each. Fillet the fish. Soak the fillets for a couple of hours in a brine made of 2 cups salt per gallon of water. Dry the fish in a breezy place for 2 to 3 hours, or until a nice pellicle forms. Cold-smoke the fish for about 6 hours.

Fry some smoked bacon in a large skillet. Remove the bacon and save it to eat with the fish. Reduce the heat to the lowest setting and sauté the smoked fillets in the bacon grease, turning them from time to time. If your skillet is large enough, also sauté some sliced portobello mushrooms. If necessary, use a separate skillet for the mushrooms. For a complete meal, serve with white rice and steamed vegetables.

Of course, this technique also provides a recipe for cooking the fish after smoking. Here are some other recipes to try using smoked fish.

This dish is one of my favorite ways of using a small amount of smoked fish. It’s also one of my very favorite breakfast dishes. Be sure to try it with either cold- or hot-smoked fish. I use scallions. For this recipe, I use about half the green tops along with the small bulbs. First, I cut off the root ends and the tips of the green parts. Then I peel off a layer and chop what’s left. I also use wild onions with green tops, but be warned that some of these are quite strong.

1 cup flaked smoked fish

6 large chicken eggs

1 tablespoon milk

2 or 3 scallions, finely chopped

2 tablespoons butter or margarine

salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

Break the fish into small pieces, or chop it with a chef’s knife. Beat the eggs with a little milk, then mix in the fish flakes and chopped green onions. Heat the butter in a skillet, add the egg mixture, and scramble until the eggs are set. Sprinkle with salt and pepper.

This makes a wonderful breakfast, especially when served with slices of luscious red homegrown tomatoes and fresh toast.

Here’s a recipe that I adapted from Kira Petrovskaya’s Russian Cookbook. Although billed as a salad, it makes a nice lunch for two people on a hot day. The olives can be either green or black, or a mixture. Black ones, however, make a more attractive salad.

1 tablespoon minced onion

1 tablespoon minced green onion, with some tops

1 tablespoon drained capers

½ cup sliced pitted olives

4 or 5 boiled small new potatoes, diced

½ pound smoked salmon

1 tablespoon wine vinegar

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 teaspoon prepared mustard

salt and pepper

Mix the onion, green onion, capers, olives, and potatoes in a bowl. Cut the salmon into fingers and mix very carefully into the potato mixture. Chill.

Prepare a dressing by combining the vinegar, oil, and mustard; season with a little salt and pepper to taste. When you are ready to serve, pour the dressing over the salmon, but do not stir it in. Eat immediately with crackers or toast.

Here’s a dish that I like to cook on a cast-iron griddle. The fish patties can be eaten as part of a meal or used in a sandwich. For the latter, all you’ll need in addition to the patties is some mayonnaise generously spread onto each slice of bread.

2 cups flaked smoked fish

1 cup fine cracker crumbs

3 green onions, minced with about half the tops

½ red bell pepper, seeded and minced

1 clove garlic, minced

2 medium chicken eggs, whisked

salt and pepper to taste

flour

butter

Mix the fish, cracker crumbs, green onions, red pepper, garlic, eggs, salt, and pepper in a bowl. Shape the mixture into patties, then dredge each patty lightly in flour. Heat a little butter on your griddle or in a skillet. Over medium heat, sauté the patties for a few minutes or until nicely browned on the bottom, then turn carefully with a spatula and brown the other sides. If the patties tend to tear apart, use two spatulas, one on top and one on bottom, for turning.

This makes 4 large patties. I need 2 for a full meal, but can get by with 1 for lunch or in a sandwich. I like to sprinkle the patties with Asian fish sauce (nam pla or nuoc mam), which can be put on the table as a condiment. Oyster sauce is also good.

According to my old edition of Larousse Gastronomique, the Irish once had a simple but unusual method of preparing smoked herring. The fish were beheaded and split in half lengthwise, spread flat in a suitable container, covered with whiskey, and flamed. When all the whiskey had burned away, the herring were ready to eat. I recently ran across the same technique in a book on British country cooking, in which the author used the term Rob Roy for cold-smoked fish prepared by this method.

One day I intend to try the method with real Irish whiskey and smoked herring, but to date, I have not had the opportunity. I did, however, prepare some at a smoked mullet fest in the north of Florida, where the tradition is to butterfly the mullet before smoking it. I selected some smaller smoked mullet and poured some sour-mash bourbon over them and burned it off. The fish were delicious. The idea got some attention in the area, and the northern Florida good ol’ boys may have picked it up.

The best avocados I have ever eaten were grown on a large tree near Tampa Bay, an area also noted for its smoked mullet. The two ingredients fit nicely together in a recipe from Ghana, which I have adapted here. Any good smoked fish will do, but those that have been cold-smoked should first be steamed or poached for about 15 minutes, or until they flake easily when tested with a fork.

4 chicken eggs, hard-boiled

¼ cup milk

½ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon sugar

2 limes

¼ cup peanut oil

¼ cup olive oil

1 heaping cup flaked, cooked, smoked fish

2 large avocados, quite ripe

Peel the whites from the hard-boiled eggs. In a bowl, mash the yolks with the milk until you have a paste. Add salt, sugar, and the juice of 1 lime. Stir in the peanut oil a little at a time, then stir in the olive oil. Chop the egg whites and add them to the bowl. Stir in the fish. (This stuffing can be refrigerated for later use, or served at room temperature.)

When you are ready to eat, cut the avocados in half, remove the pits, and fill the cavities with the stuffing. Squeeze on a little lime juice and enjoy.

In Ghana, the dish is served with strips of red bell pepper or pimiento as a garnish. This is a nice touch. I also like it sprinkled with paprika and served on lettuce, along with wedges of lime so that each person can squeeze some juice onto his serving.

Note: This stuffing is a good spread for crackers, especially when made with garlic oil (olive oil in which garlic cloves have steeped for several months; I preserve garlic in this way, then use the oil for cooking purposes).

Here’s a dish that I like to cook in a large cast-iron skillet. A large electric skillet will also work.

2 tablespoons butter

2 pounds smoked fish

salt and freshly ground black pepper

½ cup half-and-half or light cream

chopped fresh parsley or green onion tops

Melt the butter in a skillet and sauté the fish for 1 minute on each side. Sprinkle on a little salt and black pepper, then pour in the cream. Simmer (do not boil) for 5 minutes. Turn the fish and simmer for another 5 minutes. Place the fish on a serving platter and pour the pan liquid over it. Garnish with parsley or green onion tops. Serve with boiled new potatoes, steamed vegetables, and hot bread.

This dish from Britain takes its name from the Indian khichri, but one English writer suggests that the only thing Indian about it these days is the curry powder. In America, even that ingredient is sometimes omitted, thank god.

2 cups water

1 cup long-grain rice

½ pound smoked fish, cooked and flaked

½ cup butter or margarine

2 large onions, chopped

1 teaspoon curry powder (optional)

salt (if needed) and black pepper to taste

1 hard-boiled chicken egg, sliced

½ lemon

4 tablespoons light cream or half-and-half

Bring 2 cups of water to a hard boil, add the rice, return to a boil, reduce the heat, cover tightly, and simmer for 20 minutes without peeking.

If the smoked fish has not been cooked, steam or poach it until it flakes easily, about 10 minutes. Heat half the butter in a large skillet and sauté the onions for 5 minutes. Add the fish, stirring about, and mix in the curry powder, salt, if the latter is needed (depending on the salt content of the fish), and pepper. Add the sliced egg.

Melt the rest of the butter and mix it into the rice, which should be fully cooked by now. Stir the rice into the fish mixture. Squeeze the juice of half a lemon over the kedgeree, then spoon the cream over all. Serve hot. Feeds 3 or 4.

I’ve never cooked a chowder that wasn’t good (at least to me), but I’ll have to admit that I am partial to one made with smoked fish. Here’s an old recipe from Maine. Any good smoked fish can be used, hard- or light-cured, but fish with large scales should be scaled before being boiled.

1 whole smoked fish, about 1–1½ pounds

¼ pound salt pork, diced

1 cup diced onion

3 or 4 medium to large potatoes, diced

black pepper to taste

2–3 cups whole milk

Put the fish in a pot, cover it with water, bring to a boil, reduce the heat, and simmer until the fish is tender. (The time will depend on how hard it was cured and how long it was smoked.)

While simmering the fish, sauté the salt pork in a skillet until the pieces begin to brown. (Some cooks may want to put the salt pork in with the fish instead of browning it; suit yourself.) Drain the salt pork and sauté the onion in the skillet for 5 minutes.

When the fish is tender, remove it from the pot, and flake the meat, discarding the bones. Add the potatoes, salt pork, and pepper to the pot. Cover and simmer for 10 minutes. Then add the onion and simmer for another 10 minutes or so, or until the potatoes are done. Stir in the fish flakes. Slowly add from 2 to 3 cups of milk, stirring and tasting as you go. Ladle the chowder into bowls and serve with plenty of hot bread. A loaf of chewy-crusted French or Italian bread suits me better, but hot biscuits or even bannock will do. I like to grind some more black pepper onto my serving. Feeds 4.