He was accused of being friendly to sodomites. The first we know of Donatello’s David is in Cosimo’s house. It is hard to think of a better advertisement for homosexuality than this life-size naked youth in polished bronze who slays a giant to place a dainty foot on the severed head and assume an erotic pose. Hermaphroditus, a book of poems dedicated to Cosimo, was publicly burned. It promoted sodomy, said celebrity preacher Bernardino di Siena. But Cosimo never used his power to abolish the Officers of the Night, the vice police who prowled the piazzas in search of serving girls with too many buttons, perverse men in platform shoes, gay lovers caught in the unnatural act.

He was accused of being friendly to Jews. In 1437, the Florentine government conceded explicit moneylending licenses to Jews, not to Christians. But there is no indication that Cosimo opposed the law obliging Jews to wear a yellow circle of cloth. A Jew was not part of Christendom and that was that.

He was accused of usury and tax evasion. You will go to hell for benefiting from his evil earnings, Rinaldo degli Albizzi had told the Medici sympathizers. After his return to Florence, Cosimo lifted restrictions on the so-called dry exchanges. It was one of the few transactions that all the theologians agreed was usury.

He was accused of hijacking church renovation for his own glorification, of kicking out other would-be patrons, of replacing the family chapels of enemies with those of friends, of trying to buy his way into heaven, of using excommunication as a weapon to recover personal debts, of being too friendly with priests who are “the scum of the earth.”

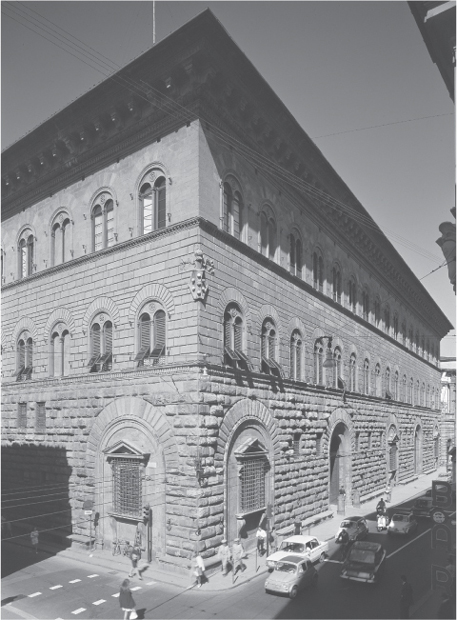

He was accused of spending fabulous sums on a huge new palazzo while others starved, and of appropriating cash from the public purse to do it. “Who would not build magnificently being able to spend money which is not his?” his detractors complained. Blood was smeared on the massive doors of the new house. Designed by Michelozzo and situated on the via Largo, just a few hundred yards north of the duomo, the Palazzo Medici had, and still has, the forbidding look of the fortress about it. There were no windows at ground-floor level, just solid stone.

He was accused of cruelty and tyranny. He exiled so many and never failed to have the standard ten-year sentence extended before expiry. Families were split and letters censored. Up and down the peninsula, paid informers monitored the whereabouts of old enemies. Ingenious codes were developed to bemuse the city officials.

He was accused of using torture. Girolamo Machiavelli, along with two like minds, was “tormented for days before being exiled.” Re-arrested for failing to stay in his assigned place of exile, Girolamo died in prison “from illness or torture.”

Palazzo Medici, the house that Cosimo built. Inside, there are two spacious courtyards; outside, the palazzo could be defended against all comers.

He was accused of directing Florentine foreign policy for his own personal gain. In 1450, he switched the city’s support from the old ally Venice to the old enemy Milan, revolutionizing the system of alliances throughout Italy. Francesco Sforza, erstwhile condottiere, now duke of Milan, was one of the largest clients of the Medici bank.

He was accused of subverting and manipulating the democratic process, of rule by intimidation, of crushing all opposition to his authority, of running a narrow oligarchy, of shamefully elevating “base new men” who would always do his bidding. One Medici wool-factory foreman eventually became gonfaloniere della giustizia, head of the government.

He was accused above all—and this accusation contained and explained all the others—of seeking to become a prince, of attempting to transform Florence from a republic to a hereditary monarchy. Why else would a man build a house “by comparison with which the Roman Coliseum will appear to disadvantage”? Aging now, with the sagging cheeks and baggy eyes we see in all the paintings, Cosimo did not trouble to defend himself. He knew he was widely loved, by many adored. The popular poet Anselmo Calderoni addressed him thus:

Oh light of all earthly folk

Bright mirror of every merchant,

True friend to all good works,

Honour of famous Florentines,

Succour of orphans and widows,

Strong shield of Tuscan borders!

Marco Parenti, son-in-law of the exiled Palla Strozzi, was implacably opposed to Cosimo and determined to bring his exiled in-laws back. On the banker’s death in 1464, however, he was obliged to remark on Cosimo’s modesty in deciding against a state funeral. He also acknowledged his enemy’s part in bringing peace and some prosperity to the city. People were grateful. “And nevertheless,” writes Parenti, “on his death everyone rejoiced; such is the love of and desire for liberty.”

Some time after the funeral, the government of the town chose to reward the dead Cosimo with the title of Pater Patriae, Father of His Country. Who is simultaneously loved and resented if not a father? However benevolently, the paternal figure holds us in check. Only the security he brings can reconcile us to waiting for his demise. Cosimo’s achievement was to make his Florentine family wait thirty years, and then some.

TO HAVE A proper understanding of Cosimo’s management of the Medici bank, one must study the 600 densely detailed pages of Raymond de Roover’s The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank. To gain a thorough grasp of the way Cosimo ran Florence while apparently retaining the role of an ordinary citizen, one must settle down for at least a week with the 450 pages and labyrinthine complications of Nicolai Rubinstein’s The Government of Florence Under the Medici. To have just some inkling of the ambiguity of Cosimo’s relationships with the Christian faith and humanism, the contradictory impulses driving his commissions of so many buildings and works of art, one must tackle Dale Kent’s exhaustive and quite exhausting Cosimo de’ Medici and the Florentine Renaissance.

These books rarely communicate with each other. Sometimes you might be reading about three different, equally remarkable careers. Yet whichever side of Cosimo you are looking at, you are always aware of this fatherly man’s special genius for holding things in check. What exactly? The destructive energies generated by the collision of irreconcilable forces: faction and community, Milan and Naples, commercial appetite and Christian morals, the love of liberty and the need for order. To hold the fort—the bank, the family, the state—in the midst of chaos, you must reconcile the irreconcilable. How? The language rebels. In the short term, is the answer, with the aid of considerable sums of money, a genius for ad hoc solutions, and the utmost discretion. Only a banker could have done it. When the money runs out, or is used without tact, your time is up.

In 1442, in his early fifties, Cosimo was the main supporter behind the formation of a new religious confraternity: the Good Men of San Martino. The idea was to help the “shamed” poor, those who had fallen on hard times but were too proud to ask for charity. The Good Men went around the town asking for donations, after which they brought relief and preserved anonymity. Fifty percent of monies collected were registered as coming from the Medici bank. The contribution is entered in the bank’s books under the heading: God’s Account.

The arrangement is emblematic of the way Cosimo works. A largesse with political implications is hidden behind a religious organization and the name of a commercial company. The amount of money felt to be coming from oneself is doubled by also having donations collected from others. The sense of guilt arising from sinful lending operations and constant tax evasion is attenuated. The danger of economic unrest in the town is reduced. By not asking for recognition or imposing yourself as benefactor, you actually attract even greater recognition. Most crucial of all to the scheme’s success, however, was a genuine charitable impulse. “The poor man is never able to do good works,” Cosimo wrote thoughtfully to his cousin Averardo. The poor get to heaven, wrote Archbishop Antonino, by bearing their tribulations with fortitude, the rich by giving generously to the poor. Such is the providence of social inequality. A Christmas or Easter handout of wine and meat distributed by the Good Men of San Martino cost Cosimo 500 florins, three bank managers’ annual salaries.

BUT SUCH SUMS were nothing compared to the cost of that greatest irreconcilable of them all: How could an international merchant bank function when most European trade was going only one way—from the Mediterranean northward—a situation exacerbated by the fact that Rome was drawing huge sums toward itself in Church tributes without even giving anything in return? Had the pope, the Curia, been based in Paris or Bruges or London, how easy everything would have been! Italy could have sent silk and spices north, then used at least part of the income in situ to pay its dues to the Church. Not too much cash need have been moved. But the opposite was the case. The Italian bank had to recover not only the payment for products sent north but also the papal dues that it was responsible for collecting. This in a world where to move money in coin was extremely dangerous. Much of the territorial expansion of the Medici bank was undertaken to deal with this chronic imbalance. The upheavals that led to the bank’s eventual collapse stemmed in large part from the growing desperation of the measures used.

In 1429 it was decided that the Rome branch would operate without capital. Deposits from clergy, together with what coin did arrive, would be sufficient. Other monies due to the Curia from abroad would provide the capital for other branches. This move freed up perhaps twenty or thirty thousand florins. Not a solution.

Inevitably, the debt of the bank’s northern operations toward its Rome branch grew. They couldn’t find ways to send the monies they owed. This was not too worrying when the operation in question was another Medici branch, but it was dangerous when the organization holding the money was an independent agent operating on the bank’s behalf. In the first decade of the century, the Medici had established relations with such agents in London and Bruges. These were other Italian banks that collected papal dues and sold luxury merchandise for the Medici bank. They were under instructions to seek out quality wool to send back to Italy (and the Medici factories) in order to balance the flow and make the return trip worthwhile for the galleys that had brought Italian products north. The banks thus aimed to create the trade that they had come into being to assist and exploit.

But there was a problem. The English now wanted to work all their wool themselves and imposed severe export restrictions and exorbitant duties. The flow did not balance and never would. In 1427, Ubertino de’ Bardi in London and Gualterotto de’ Bardi in Bruges owed the Medici bank the huge sum of 22,000 florins, most of it due to the Rome branch. Those Bardi! Did their slowness in paying really have to do with problems finding merchandise or letters of credit going south? After all, holding someone else’s cash interest-free is always convenient. Was there some connivance, perhaps, between Ubertino de’ Bardi, a free agent in London, and his brother Bartolomeo de’ Bardi, the Medici director in Rome? Not to mention the Medici’s general manager, Ilarione di Lippaccio de’ Bardi, in Florence. This couldn’t go on. At some point, the Medici bank would have to form its own branches in both Bruges and London, if only to invest the income that couldn’t easily find its way back to Italy.

ON RETURNING TO Florence from exile in 1434, Cosimo cut all the Bardi family out of his extensive operations. A clean sweep. What had they done in his absence? We don’t know. The richest Bardi, related by marriage to Palla Strozzi and working for Cosimo’s cousin Averardo’s bank, was exiled. The man was dangerous. Averardo himself had died in exile. Bringing families together in complex relationships might make for strength, but it could also create the conditions for conspiracy and betrayal. Here was another balance that would have to be struck and restruck, year in and year out. What Cosimo’s Bardi wife thought about it, we do not know.

The Portinari family now took the place of the Bardi. Running the Venice branch, Giovanni Portinari was one of the most important men in the organization. Still nervous about the political situation in Florence, Cosimo had shifted much of the home bank’s capital to Venice. In 1431, Giovanni’s brother, Folco, running the Florence branch, had died, leaving seven children. Cosimo took three boys into his own family: Pigello aged ten, Accerito aged four, and Tommaso aged three. All would eventually hold key positions in the Medici bank.

Was this what Cosimo, who only had two children of his own—two legitimate children—planned? That the Portinari boys, brought up in his home, would be more indebted to him, better servants of the bank than any Bardi could be? If so, it was an error. Nothing is less certain than the gratitude of those who have seen us in the role of father, those who have sensed, perhaps, that the real sons are being preferred. There was some question as to whether the Portinari boys had received all the money they should have when their real father died. Folco had had considerable investments in the Medici bank.

Meantime, it was another Portinari, Bernardo, son of Giovanni in Venice and older cousin of the boys in Cosimo’s care, who set out for Bruges and London in 1436 to look into the ever-present problem of the trade balance. Traveling through the Alps on horseback, Giovanni goes first to the Medici branch that Giovanni Benci has set up in Geneva. With Paris in chaos thanks to the interminable Anglo-French War, Geneva is a big success. Merchants come to its four annual trade fairs from all over Western Europe; the town is thus an important sorting house for much of Europe’s currency. Everybody needs credit; exchange deals abound. Merchandise from the north can be brought at least halfway to Italy, turned into cash, and then sent on by messenger. The city even coined a new currency for all international dealings at the fairs: the golden mark, first hint at the euro perhaps.

After Geneva, Bernardo rode on to Basle, where Cosimo had set up another branch—not to trade, but simply to service the cardinals and bishops meeting there in acrimonious general council since 1431. Papal authority was the matter in dispute. By 1436, the Church was once again on the brink of schism. Pope Eugenius, still living in Florence, had abandoned proceedings. The Holy Father’s banker needed to have a sense of who would gain the upper hand, though of course he would never shrink from taking deposits from both sides.

Traveling on to Bruges and London, Bernardo’s brief is to get the local agents to speed up their sale of goods sent by the bank and, even more important, the return of money to Italy. He has special powers of attorney to have particularly recalcitrant debtors taken to court and imprisoned. The sad truth is that your debtor priest in Basle is a safer bet than your merchant debtor in London. Threatened with excommunication through Cosimo’s papal connections, a bishop must pay up. His livelihood and identity are at stake. But there were merchants who took no more notice of a bull of excommunication than a condottiere would of this or that count’s title to some citadel or town. “If only he was a priest,” comments one Medici accountant, preparing to write off a bad debt, “there might be some chance.”

But the real reason for Bernardo Portinari’s trip north was to see if conditions were favorable for opening Medici branches in Bruges and London. Were the local merchants solvent? Were the judges fair to foreigners? What was the level of anti-Italian sentiment in the English wool trade? Considerable. Would the king waive the wool-export monopoly run by the English Merchants of the Staple if the Medici bank lent him ready cash? If lent cash, would the king pay it back? Was the Anglo-French War threatening trade between London and Bruges? How long was the king likely to be king anyway?

Bernardo Portinari’s father died while he was away. He returned to Italy, gave a positive report, then went back to England with a papal bull regarding the appointment of the bishop of Ely and the collection of 2,347 Flanders grossi (about 9,000 florins), much of which was dispatched to Geneva hidden in a bale of cloth. Risky stuff. But profitable. In 1439, a Bruges branch was opened with a secondary office in London. The initial capital was a mere 6,000 florins, all provided by the branch in Rome. In 1446, London became a branch in its own right, with capital of £2,500. At this point, the Medici bank has eight branches of its own and agents in at least eleven other banking centers.

FROM THE GREEN-CLOTH–COVERED table in via Porta Rossa, from the palatial rooms of his great house, now home to the Medici holding, from his private prayer cell in the Monastery of San Marco, Cosimo’s mind reaches out across Europe. He has no phone, no e-mail. The letters arrive regularly, bringing last week’s exchange rates, coded secrets, the latest politics and war news. Replies are dictated, copies made. The director in Rome is complaining about the director in London. I won’t accept second-rate cloth as payment! I want cash. The duke of Burgundy is again defying the French. The coin arriving from Geneva is no longer current and will have to be re-minted. Aren’t my managers spending too much time retrieving money from each other? That boy you sent us, Bruges objects, he can’t even read or write! Why won’t the women of Flanders buy Florentine silks? Our sales rep is so handsome, speaks French so well! You were told not to underwrite insurance on shipping, Cosimo reminds London. The ship was sunk before the premium was paid! Perhaps the theologians are right in complaining how exchange deals in Geneva always run from one fair to the next. It amounts to a loan with interest. But what can a banker do? What can I do to pay less tax? The balance sheet must show only half of the capital invested, Cosimo instructs the director of the Venice branch. And then there was Lubeck. Will the Hanseatic League never let us into Eastern Europe?

Cosimo has Giovanni Benci beside him now as general director of the Medici holding. They work together among the tapestries and sculptures of Cosimo’s house. Benci had made quite extraordinary profits in Geneva. He is astute and gifted and devout. Pondering the accounts together by the light of an open window, do the two men occasionally exchange a snigger over the slave girls, the days in Rome? Are they in agreement with the general Florentine complaint that it’s getting hard to distinguish an honest girl from a prostitute? Do they discuss their contributions to religious institutions, exchange the names of favorite artists—Donatello, Lippi—discuss the latest translations of Cicero, the seductive ideas of the humanists? Why aren’t the Florentine whores happy to wear bells on their heads? Why can’t the Western and Eastern churches agree about the nature of the Trinity? Does the preacher Bernardino di Siena really believe, as he has been claiming in his sermons, that Jews take delight in pissing in consecrated communion cups? Cosimo is now an important figure in the religious confraternity dedicated to the Magi. Contessina fusses over what cloaks he should wear when he rides down the city streets to reenact the three kings’ adoration of the Holy Child.

Together, Giovanni Benci and Cosimo open a Medici branch in Ancona in 1436. This Adriatic port was important for exporting cloth to the East and importing grain from Puglia, farther down the coast. But could that justify the huge capital investment of around 13,000 florins, far larger than the Medici investment in the more important commercial centers of Venice and Bruges? Florence was at war. Once again the Italian scenario was fantastically complicated: a succession dispute down in Naples between the Angevin and Aragon families; the two condottieri, Francesco Sforza and Niccolò Piccinino, at each other’s throats in the Papal States; the pope marooned in Florence, afraid of going back to Rome, worried about developments in Basle, casting about for allies; Duke Filippo Visconti in Milan, with Piccinino in his pay, seeking to capitalize on the turmoil in every area, sending expeditions to Genoa, Bologna, Naples. And now Rinaldo degli Albizzi has left his place of exile and is begging Visconti to attack Florence and restore his family’s faction to power. Undaunted, the incorrigible Florentines are once again launching an assault on Lucca and calling on the Venetians to help them out when it comes to the crunch with Milan. We would, if the Mantuans hadn’t switched sides, the Venetians reply. In the midst of this confusion, Cosimo made a long-term decision to back the great soldier Sforza. The money down in Ancona was not to finance trade at all. Or not exclusively. Ancona was in Sforza’s sphere of operation. It was the Medici bank’s first serious move into funding military operations that were not specifically to do with Florence. Why?

In Milan, the fat, mad, aging Visconti had no legitimate off-spring, just one bastard daughter, Bianca. Sforza wanted her for his wife, together with the Milanese dukedom. He wouldn’t fight against Visconti while that marriage was in the cards. Or not north of the Po, in Visconti’s sphere of influence (he later changed his mind). At the same time, the combination Sforza–Visconti, should the condottiere fight with the duke, was the one feasible alliance capable of inflicting decisive military defeat on Florence. The duke had tied Sforza’s hands with the tease of his daughter, constantly promising that the marriage was about to take place, then inventing reasons for delay. Cosimo responded by tying the condottiere with his cash. Sforza could hardly fight for Visconti and the Albizzi if his army was fed and clothed by the Medici.

The Ancona adventure, though short-lived, marked a turning point in the history of the bank. It fused its destiny with that of the Florentine state. Here was a branch that lent mainly for political purposes, without expecting to recover its capital. Not good news for the small investor. Matters of state go beyond the rationale of any commercial venture. Thirty years later, Sforza would owe the Medici bank something in the region of 190,000 florins, a sum far beyond repayment. This was how the Bardi and Peruzzi banks had gone under years ago. But in 1440, Piccinino, Milan, and the Albizzi faction were decisively beaten by the Florentines at Anghiari, to the south east of the city. Sforza, the most successful military adventurer of the fifteenth century, was up north fighting in the Veneto. He never attacked Florence, despite the fact that the Florentines were his future father-in-law’s bitterest enemies.

IT WAS THE period of the bank’s maximum expansion. In 1442, a branch was set up in the subject coastal town of Pisa, whence the Florentine galleys set out every spring for Bruges and London. State-built and with a monopoly on all sea trade in and out of Pisa and Florence, the galleys were rented to merchants who then sold space to others. The right to rent for each voyage was auctioned off in a contest that lasted an hour, or the time it took for a particular candle to burn out. The smarter merchants waited till the flame began to gutter before beginning to bid. So it was decided that the auction would end with the chiming of the clock on the tower of the Palazzo della Signoria—audible but not visible from the auction room. Without a wristwatch, this was nerve-wracking stuff. The palazzo’s clock-minder was put under armed guard for the duration, lest the hour should shrink or expand. In this etiquette-obsessed world, cheating is the rule. Alertness is all. Nobody is fooled, for example, when the auctioneer plants dummy bids to get things going.

To set up a branch of the bank meant finding a house with a suitable room for the obligatory green table, as well as storage space for goods in transit. The half-dozen employees would then live and eat there together. To oversee the new venture in Pisa, Cosimo went to the town himself. For a two-month stay away from home, he took with him a trunk of books and his best ceremonial armor. He collected the stuff: swords with red velvet sheaths, painted lances, a silver-decorated helmet with a crest in the form of a gilded eagle, a shield picturing a young girl. He also collected books, of course, and was friends with Florence’s leading humanists, who wrote or translated those books and often dedicated them to him. Common to the two areas of interest—books, arms—was the vision of a noble, superior man with an innate dignity that had nothing to do with Christian humility, the kind of dignity that painters and sculptors were learning to conjure up in the faces and postures of their figures.

“Only the little people and lower orders of a city are controlled by your laws …,” says a speaker in one of humanist Poggio Bracciolini’s philosophical dialogues. Cosimo had once taken time out with Poggio to explore Roman ruins in Ostia. “The more powerful civic leaders transgress their power.” That was an interesting idea, for a civic leader. It referred to the kind of man, surely, who, if he hadn’t suffered from crippling gout, might have worn a helmet with a gilded eagle.

Along with all the calculation of profit and loss, there is, then, in Cosimo’s mind, an ideal of fame and fine deeds that will survive the grave. “All famous and memorable deeds spring from injustice and unlawful violence,” says Poggio’s man in the dialogue. What a shame, Cosimo complained, that they had never captured Lucca! Perhaps one day, if sufficiently well paid, Francesco Sforza would help them do that. Then he, Cosimo, would be remembered as the city’s leading citizen when Lucca was taken, as the Albizzi family, though exiled, was still remembered for having taken this proud town of Pisa, where, as always when establishing a new branch, Cosimo now faced the problem of how to register the operation. If a branch was registered with the Medici name, it would have more prestige and attract more investment. But in that case, the Medici holding would have to assume unlimited liability. If it took the name of the resident local partner who actually ran the branch, then Medici liability was limited to the capital actually invested, but the branch’s prestige would suffer. Despite his ceremonial armor and incendiary reading, cautious Cosimo almost always opted for the latter solution, at least for the first few years. The Pisa branch opened under the names of Ugolino Martelli and Matteo Masi. In 1450, when serious losses forced the Medici holding to put a limit on its liability in the London and Bruges branches, which thus renounced the Medici name and emblem, the other Italian merchants took pleasure in the reversal and “cawed like so many crows.” Like profit and loss, renown and ridicule are never far apart.

One wished to be honored long after one was dead, like a Roman senator (Cosimo collected Roman coins as well), but by that time, surely, the superior man would have humbled himself before his Maker and flown to heavenly glory, where such earthly honor could hardly matter. There was even the danger that chasing earthly honor might cost you your place in heaven.

Here, then, was another set of irreconcilables, and if the conundrum this time lay in the mind, or in metaphysics, rather than in the balance of world trade, it was no less urgent for that. Florence had two ideal visions of itself: It was the true inheritor of ancient Rome, eternal renown, wise republicanism; and it was also the city of God. Why else would the government insist that prostitutes dress as described in the Book of Isaiah? Why would there be talk of a crusade to bring the Holy Sepulchre to Florence? Centuries later, England would entertain the same delirium of piety and empire, producing that curious hybrid, the Christian gentleman. Some Americans still think these thoughts today, trying not to see the contradictions between Christian Puritanism and world domination.

Enamored of both visions, Cosimo attended regular discussions with Bracciolini, Niccoli, and other avant-garde humanists, and likewise regular meetings of the religious confraternity dedicated to the Magi. That he did sense a contradiction between political ambition and religious belief is evident from his famous remark, upon being accused of cruelty in exiling so many enemies, that “you can’t run a state with paternosters.” Christian charity takes the back seat when you’re dealing with political necessity.

But contradictions, of course, were there to be overcome. That had always been Cosimo’s attitude. And when it came to the conflicting claims of Christian devotion and secular fame, the most effective way to resolve the problem, as Cosimo had learned from the commissioning of Giovanni XXIII’s tomb, was through art and architecture. “I know the Florentines,” Cosimo told his bookseller and later biographer, Vespasiano da Bisticci. “Before fifty years are up we’ll be expelled, but my buildings will remain.” Most of those buildings were religious. You lavished money on the sacred, to gain earthly fame. And a place in heaven. Apparently you could have your cake and eat it too. Or have your wife drunk and the wine keg full, as the Italians say.

Having “accumulated quite a bit on his conscience,” Vespasiano tells us, “as most men do who govern states and want to be ahead of the rest,” Cosimo consulted his bank’s client, Pope Eugenius, conveniently present in Florence (hence more or less under Cosimo’s protection) as to how God might “have mercy on him, and preserve him in the enjoyment of his temporal goods.” This was shortly after his return from exile.

Spend 10,000 florins restoring the Monastery of San Marco, Eugenius replied. It was the kind of capital required to set up a bank.

The monastery, however—a large, rambling, and crumbling structure within two minutes’ walk of both the duomo and Cosimo’s home—was presently run by a bunch of second-rate monks of the Silvestrine order reported as living “without poverty and without chastity.” Unforgivable. I’ll spend the money if you get rid of the Silvestrines and replace them with the Dominicans, Cosimo said. Those severe Dominicans! Only the prayers of men whose very identity was grounded in poverty and purity would be of use to a banker with an illegitimate child.

This was 1436, the year Pope Eugenius reconsecrated the duomo upon the completion, after more than fifteen years’ work, of Brunelleschi’s huge dome. With a diameter of 138 feet, the dome was the most considerable feat of architectural engineering for many hundreds of years. Its red tiles rose even higher than the white marble of Giotto’s slender ornamental tower beside the cathedral’s main entrance, and the two together completely dominated the skyline of the town in yet another ambiguous combination of local civic pride and devotion to faith. The Florentines, in fact, had for years been anxious that the dome would collapse, thereby inviting the ridicule rather than admiration of their neighbors.

On the occasion of the consecration, Cosimo bargained publicly with Eugenius to get an increase in the indulgence that the Church was handing out to all those who attended the ceremony. The pope gave way: ten years off purgatory instead of six. It cost no one anything and brought both banker and religious leader great popularity. On the matter of San Marco, the pope again proved flexible. The Silvestrines were evicted. The rigid Dominicans were moved in from Fiesole. Their leader at the time was Antonino, later Archbishop Antonino, a priest with a streak of fundamentalism about him. What would our Saint Dominic think, he wrote after the expensive renovation was complete, if he saw the houses and cells of his order “enlarged, vaulted, raised to the sky and most frivolously adorned with superfluous sculptures and paintings”?

But this fundamentalism was indeed only a streak—only a would-be severity, if you like—otherwise the priest could hardly have worked together with the banker for as long as he did. For the story of Cosimo’s relationship with Antonino, who oversaw the lavish San Marco renovation project and then became head of the Florentine church for most of Cosimo’s period of power, is the story of the Church’s uneasy accommodation with patronage of dubious origin. “True charity should be anonymous,” Giovanni Dominici, militant leader of the Dominican order, had insisted. “Take heed,” Jesus says, “that ye do not your alms before men, to be seen of them; otherwise ye have no reward of your Father which is in heaven.” The position is clear: no earthly honor through Christian patronage. But Antonino and Cosimo were both sufficiently intelligent to preserve those blind spots that allow for some useful exchange between metaphysics and money: in the ambiguous territory of art. In return for his cash, the banker would be allowed to display his piety and power. And superior aesthetic taste. The Church would pretend that all this beauty was exclusively for the glory of God, as it readily pretended that the building of the duomo’s cupola had nothing to do with Brunelleschi’s megalomania. Without such dishonesty, the world would be a duller place.

Michelozzo, more than ever Cosimo’s personal friend after sharing his period of exile, was the architect. The monks’ cells would be suitably austere. The library, with its rows of slim columns supporting clean white vaults, was a miracle of grace and light. Cosimo donated the books. Many were copied specifically for the purpose. Many were beautifully illuminated. The main artist in the project was Fra Angelico, otherwise known as Beato Angelico, a man who wept as he painted the crucifixions in all the novices’ cells. Quarrel with that if you will. Antonino insisted on crucifixions, especially for novices. The true purpose of art is to allow the Christian to contemplate Christ’s agony in every awful detail. But at the top of the stairs leading to those cold cells, Angelico’s Annunciation presents two sublimely feminine figures generously dressed as if by Florence’s best tailors. And in the church below, the monastery’s main altarpiece, The Coronation of the Virgin, shows just how far Cosimo has come since the tomb of Giovanni XXIII.

Holding her unexpected child, the Virgin sits crowned with banker’s gold in a strangely artificial space, as if her throne were on a stage, but open to trees behind. It was the kind of scene the city’s confraternities liked to set up for their celebrations, funded of course by benefactors such as the Medici. Aside from San Marco and San Domenico (patron saints of the monastery and of its newly incumbent order), the figures grouped around the Holy Mother are all Medici name-saints: San Lorenzo, for Cosimo’s brother, who had recently died; San Giovanni and San Pietro for Cosimo’s sons. Kneeling at the front of the picture, in the finest crimson gowns of the Florentine well-to-do, are San Cosma and San Damiano. Cosma on the left, wearing the same red cap that Cosimo prefers, turns the most doleful and supplicating face to the viewer, the Florentine congregation. Apparently he mediates between the people and the Divine, as Cosimo himself had done the day he got the pope to hand out ten years’ worth of indulgences instead of six. Damiano instead has his back to us and seems to hold the Virgin’s eyes.

In later years, other managers of the Medici bank—Francesco Sassetti, Tommaso Portinari, Giovanni Tornabuoni—would have themselves introduced directly into biblical scenes. Solemn in senatorial Roman robes as they gazed on the holy mysteries, they showed that at least in art there need be no contradiction between classical republic and city of God, between banker and beatitude. Cosimo had more tact. He appeared only by proxy, in his patron saint. Or saints. For he never forgot to include brother Damiano, perhaps half hidden by Cosma’s body, turned toward the Virgin, or the crucifixion, as if half of the living Cosimo were already beyond this earth, in heaven, with his dead twin brother. No doubt this generated a certain pathos. “Cosimo was always in a hurry to have his commissions finished,” said Vespasiano da Bisticci, “because with his gout he feared he would die young.” He was in a hurry to finish San Marco, in a hurry to finish the huge renovation of his local church, San Lorenzo, then the beautiful Badia di Fiesole, the Santissima Annunziata, and many others as the years and decades flew by, including the restoration of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Ever in a hurry, he grew old fearing he would die young. Perhaps it was this that made him such a master of the ad hoc.

Fra Angelico’s Coronation of the Virgin, one of the many paintings commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici when he undertook the restoration of the monastery of San Marco. Six of the eight saints in attendance are Medici name saints, with St. Cosma turning to face the congregation in the foreground to the left, balanced by San Damiano on the right. Around the edge of the luxurious carpet run red balls on a golden field, the motif of the Medici family. The sacred space thus becomes more comfortable, for the rich.

WHEN THE RESTORATION of San Marco was finally finished in 1443, Pope Eugenius, now with his bags packed ready to return to a pacified Rome, agreed that the church should be reconsecrated under the name San Marco, San Cosma, and San Damiano. So Cosimo reminded everyone of his part in the project, but unobtrusively, as with the Good Men of San Martino. Not for him the gesture of the banker Giovanni Rucellai, who advertised his personal patronage by having his name written in yard-high letters right across the façade of Santa Maria Novella. All the same, an attentive observer would have noticed, in that San Marco altar-piece, a line of red balls around the lovely carpet on which the family name-saints knelt before the gorgeous Virgin. Were they really the red balls of the Medici family emblem? There were no Last Judgments in Cosimo’s San Marco. Discreetly, head bowed and cap in hand, the profane invaded the sacred space and made it comfortable.

Cosimo practiced the banker’s art of unobtrusive proximity. It wasn’t enough that men dedicated to poverty had accepted his money and its role in their scheme of things, thus giving tacit approval to his business practices; they must also admit him right into their community, accept that he was one of them. So he had a cell built for himself beside the monks’ cells. Except that Cosimo’s cell had two rooms. It was larger and pleasanter. Over the door, engraved in stone, were the words of the papal bull that granted him absolution from all sins in return for his expenses. Few eyes would see this, but Cosimo wanted it written down, indelibly, like a bank contract that only the interested parties need consult. “Never shall I be able to give God enough to set him down in my books as a debtor,” he remarked humbly of his huge outlay for San Marco. Yet clearly that was the kind of relationship he would have preferred.

Opposite the door of the first room of Cosimo’s cell, on a wall that novices might glimpse as they walked along the corridor, was one of Fra Angelico’s crucifixions. How could the monks not approve? But in the larger, private cell behind, with more expensive paints and stronger colors, Cosimo had the younger, more cheerful artist, Benozzo Gozzoli, assist Angelico in painting a procession of the Magi. It was Cosimo’s favorite biblical theme. He would be responsible for at least half a dozen such pictures in his lifetime. All in bright colors. Fifteen years after San Marco, around three walls of the tiny chapel in the heart of his great palazzo, he and his son Piero had the same Gozzoli paint a lavish Magi procession in which, for the few who penetrated that sanctum, Cosimo himself at last appeared in person, riding on a mule behind the youngest of the three Magi. Common to many of the Florentine elite, the Magi obsession is easily explained. What other positive images of rich and powerful men did the New Testament offer?

Gozzoli’s Adoration of the Magi (detail). Only in this fresco, painted around three walls of the tiny chapel in the heart of his great palazzo, did Cosimo at last allow himself to be depicted in a biblical scene. Typically unobtrusive, he wears black and rides a mule, while to his left (our right), son Piero is rather more magnificent on a white horse.

Cosimo’s extension of his Church patronage beyond his own neighborhood and eventually all over town, the numerous depictions of Saints Cosma and Damiano, the raising of the Medici arms, the red balls on a golden field, in one sacred place after another—all this has been read, rightly no doubt, as the symbolism of political ambition. Certainly it caused resentment among those who felt their territory had been invaded, those exiles who lost their family chapels to members of the Medici clan.

The slow seeping of the sensual into sacred art, the more and more accurate depiction of the human form and the contemporary secular space, the growing physical beauty of the Madonna, the awareness of her breasts, her nipples even, the elegance of her long neck—all this has been understood as evidence of a new interest in everything earthly, a more positive humanist-inspired vision of our worldly lives. Rightly, no doubt. But there is more to it. There is magic.

What were the Magi if not magicians? They came to Jesus because that proximity was important to them. The gifts they brought had magical powers. Fourteen centuries later, the Florentines might be fascinated by money and material goods, but they hadn’t reached the dull point where matter is just matter, or where symbolism is merely an artistic convention whereby abstract qualities can be evoked through this or that image. No, for the people of Cosimo’s generation, a certain kind and color of dress, a particular hat, or a diamond ring still possessed powers that went beyond their being indicators of material wealth. Treated or processed in a certain way, material things could take on magical force. What was that rhinoceros horn doing in the Medici bank’s warehouse, if not waiting to be ground up in a magic potion? The bones of a dead saint were also alive with magic. Keep them close and they will work miracles. To show reverence, to encourage the miracle, you put them in an elaborate reliquary, a work of the finest craftsmanship, of Ghiberti, or Donatello. Art and magic call to each other.

But alas, saints’ bones are scarce. And rhinoceros horns even more so. When the great preacher, misogynist, and anti-Semite Bernardino di Siena died in 1444, the popular enthusiasm to possess some object that the charismatic man had touched left his poor donkey stripped of all those hairs that had rubbed the holy backside. Afterward, when the buying and selling began, how could you tell one donkey hair from another? How can you tell a real relic from a fake? The holy foreskin of our circumcised Lord is still held in one church in Italy. In 1352 the Florentine government had bought an arm of Santa Reparata from Naples, only to find it was made of wood and plaster.

But if you couldn’t find or afford the saint himself, the real thing, there was always his painted or sculpted likeness. The faithful kissed the saint’s stone feet, brushed his painted gown with theirs. They were close to him, through art. The banker Giovanni Rucellai had his tomb made in an exact likeness of the Holy Sepulchre. This mimicry could only make the passage to heaven easier. The copied image, that is, had a virtue that went beyond an aesthetic appreciation of the sensual world. It appropriated the qualities of its model. It served to create proximity to the sacred. The craftsmanship of the reliquary and the power of the relic were fused together in the fine fresco that showed, convincingly, the saints about their miracles.

Donatello’s reliquary bust of San Rossore (museum of S. Matteo, Pisa). Renaissance high art fuses with the miracle-working power of the saint’s remains.

Fortunately, Cosimo had an eye for the gifted artist, as he had a nose for the trusty bank manager. Donatello might be a sodomist, but who else could make you feel you were so close to the Divine in bas-relief? His reliquary bust of San Rossore was the man himself in bronze. Fra Filippo Lippi might be a fornicator, liar, and cheat, but how real your patron saints were when painted in pride of place either side of the pure Virgin in the Church of Santa Croce. Cosma, Cosimo. The proximity of those names had meaning (all branches of the Medici bank observed a holiday on September 27, St. Cosma’s Day). The cloak San Cosma wore in Lippi’s painting was the same crimson as Cosimo’s. He looked out at the devout viewer. The Virgin prayed for the saint, the saint for the viewer. Cosimo paid for prayers for the Florentines, prayers for his family, prayers for himself. Every day. The monks took the Medici bank’s money, lived with the paintings, and prayed. A magical community had been formed—real, virtual, metaphysical. Pay, pray. This was the early Renaissance. Pagare, pregare. Wealth, devotion, and technique reconciled in the sorcery of art. Money rehabilitated. Antonino and Cosimo could get on.

Or perhaps not. “I invoke God’s curse and mine on the introduction of possessions into this order.” The words appear on a scroll held by a saint in another of Fra Angelico’s depictions of the Virgin in San Marco, this time in a dormitory corridor where the only viewers would be the monks. Someone wasn’t happy. Cosimo had asked for the restriction on bequeathing money to the Dominican order to be lifted, but the monks were resisting. They hadn’t committed their lives to the severest of disciplines in order to grow rich. Was it right for a moneychanger to occupy such a position in their community? There was a sell-by date, it seemed, on much of what Cosimo did. Whether in the field of banking, or religious art, or politics, the magical balancing act, the expensive reconciliation of the irreconcilable, could last only so long.

IN 1438, HARD-PRESSED by the Turkish war machine, the leaders of the Eastern Church had come to Ferrara to see if they could resolve their doctrinal differences with the pope, accept his authority, and in return get help to raise the long siege of Constantinople. When Ferrara was hit by the plague, Cosimo took advantage to invite the Church leaders to Florence. Medici money brought the Orient to town, their strange clothes, their Greek manuscripts. Medici money paid for their lodgings, their food, their meeting places, as banking money today pays for so many well-meaning conferences.

Does the Holy Spirit proceed only from God the Father, as the Eastern Church maintained, or from both God the Father and God the Son, as Rome insisted? That was the issue under debate. It must have seemed child’s play to a man used to the stubborn complexities of international trade. Surely one just decided, this or that. And after months of bitter dispute, the priests did in fact agree that Rome was right. Christendom rejoiced. Cosimo had played his part in resolving the schism that was the shame of every believer. But back in Constantinople, the Greek holy men were told they had exceeded their mandate, they had conceded too much, they had merely accepted the authority of the pope. The pact broke down. Even at the expense of annihilation, the Greeks didn’t want to accept that they had got it wrong about the Holy Spirit. And if they persisted in such grave errors, Western Christendom could hardly be blamed if it left their eastern cousins alone against the mighty Turk. Even the most pious of bankers could do nothing about such determined integrity.

And there was very little Cosimo could do when the company of Giovanni Venturi and Riccardo Davanzati failed in Barcelona in 1447. Venturi & Davanzati, one of many Italian trading companies in Spain, had played a critical part in the process by which the Medici bank sought to keep money circulating among its various branches. The Barcelona company bought cloth from the Bruges branch of the Medici bank. The money it owed Bruges was then held in the Spanish city, to be drawn on by the Venice branch of the Medici bank to honor letters of credit issued to Venetian merchants who were importing saffron and Spanish wool. The merchant handed in his money to the Medici branch in Venice and Venturi & Davanzati paid it out to his suppliers in Barcelona. In this way, Bruges reduced its debt with Venice and with Italy in general.

But in the summer of 1447, the Spanish company was unable to honor 8,500 florins’ worth of letters of credit. The Venetian merchants demanded their money back from the Medici. Bruges was left without payment for vast quantities of cloth and above all without a way of returning money to Italy. With the elaborate system of triangular trading on which the Medici bank depended becoming ever more precarious, the only solution now seemed to be to encourage Henry VI of England to accept loans in return for which he would allow the Medici to increase the amount of wool they were buying and sending to Italy. The loans would be repaid by exempting the Medici from export duties on whatever they bought.

It was a dangerous and expensive way of bringing money back to Italy, since it involved the constant concession of large amounts of credit. Medici managers set off for Contisgualdo (the Cots-wolds) to watch the sheep shearing, then down to Antona (Southampton) to arrange for transport. With the monopoly of their own trade organization bypassed, the English wool merchants were furious. And many of the Florentine monks were likewise getting increasingly irritated about the number of bankers appearing in sacred paintings and demanding pride of place in their prayers. It seemed the more money you spent on those who wished to stay pure and poor, the greater the possibility of a fundamentalist backlash. Everywhere tension was building. In 1452 Girolamo Savonarola was born. Less than half a century hence, this fiery preacher would be running Florence and the Medici would have fled. Albeit briefly, the city of God would replace the Medici regime. In the political field as elsewhere, Cosimo’s solutions always had a precarious feel about them.

THERE WAS A question that from time to time would form on the lips of the Florentine ruling elite: Should we admit such and such a person—a foreigner, an ambassador, a vulgar self-made man—into “the secret things of our town”? But surely, you object, in an open republic with a written constitution, there are no secrets, aside from military matters. What was this about?

On return from exile in 1434, Cosimo held no institutional position. He was a private citizen whose sentence had been revoked. He was the head of a triumphant faction taking power from another. Factions were illegal. The government, as we have seen, was elected by lot: at the top the signoria, which is to say eight priors and the gonfaloniere della giustizia. They proposed all legislation and held the powers of chief magistrates. Then the advisory bodies of the Sixteen Standard Bearers and the Twelve Good Men; then the Council of the People and the Council of the Commune, whose one power, but considerable, was that of a veto on legislation proposed.

What did Cosimo have to do with all this? What more could he be than another name in the leather bags from which, at staggered intervals, the podestà—a sort of mayor with no political power, usually a man from out of town—would select the members of the various government institutions, at random? The names in the bags were determined by a “scrutiny” held once every five years that assessed the male population on such criteria as age, wealth, family, guild membership, criminal record. On ousting the Medici in 1433, the Albizzi had held an unscheduled scrutiny to have the right sort of names put in the bags. Their great mistake had been not to eliminate the names of the previous scrutiny but merely to add new ones. Thus, with bad luck, it had happened that a pro-Medici signoria had been picked.

Whenever the process of government was stalled, when the priors kept proposing as essential something the councils repeatedly vetoed as nefarious, then, as we recall, a parliament was called. The people flocked into the Piazza della Signoria and were bullied into conceding draconian powers. One says, “flocked,” but in this archive-obsessed state, no accurate record was kept of the numbers of people in the piazza for a parliament. Nor of the way the vote split. It didn’t split. This was an exercise of pure power, thinly dressed as democracy.

Why did the priors not call a parliament more often? Because the democratic rags were so very thin that not only did they fool no one, they didn’t even allow people to pretend that they had been fooled. It had become important for the Florentines, as it is important for us today, to imagine that they shared, as equals, in a process of collective self-government. Should this patently not be the case for any extended period of time, then rebellion became legitimate. But as with the question, When is an exchange deal a loan with interest? or again, When is church patronage an expression of secular power? appearances, perceptions, definitions, and above all words were of the utmost importance. A coup d’état, for example, is called a parliament.

“The secret things of our town.” The Florentines used the expression frequently, understood what it meant, and did not clarify. They did not clarify because they were referring to the embarrassing gap between the way things were supposed to be done and the way they were really done.

COSIMO RETURNS FROM exile. A parliament is held. It ratifies the formation of a balia, a large council that wields unlimited powers for a limited period. This is a wonderful equivocation. Unlimited power for a day can cast its shadow years hence. They could execute you. The balia confirms the sentences of those members of the Albizzi clan who have been exiled and announces more sentences. It invalidates the pro-Albizzi scrutiny of 1433 and orders the name tags it produced to be burned. It appoints a group of so-called accoppiatori to make a new scrutiny. Accoppiatore means “he who brings together”—he, that is, who couples the right names with the right bags, for some people will be suitable for serving on the Council of the Commune but not on the powerful otto di guardia, the commission of eight police chiefs. Some will be equipped for sitting on the city’s public debt commission, but not for being governor of Pisa or Volterra.

Question: How can the priors, the signoria, be elected while the complex procedure of reviewing the whole male population to make the new scrutiny is carried out? Answer: The accoppiatori—Cosimo’s inner circle—will stick just ten names, from Cosimo’s inner and outer circle, into each election bag and the podestà will draw the government from those. This procedure, the balia ruled, was to last just a few months; accoppiatore is a temporary appointment. But the deadline for completing the scrutiny was put back—first to April 1435, then June, then October, then November, then March 1436. All in all, it was proving much easier to deal with a handful of names than with thousands.

In June 1436, the scrutiny is finally ready but the Councils of the People and of the Commune are persuaded to pass, by a single vote, a law that allows the priors to extend, for a year at a time, the right of the accoppiatori to prepare electoral bags with just ten names. And they do. For one year. Then another. It seems these shady civil servants have a regular job. Accoppiatore was beginning to take on the meaning “fixer.” The priors extended their powers for a third year, at which point it was almost time for another scrutiny, though the names of the previous one have never really been used. But now there is a war on, and government finances are in desperate straits. This is not a time for the divisive business of scrutinizing the population and deciding who has a right to do what. Solidarity is at a premium. Month by month, election after fixed election, the podestà’s extractions of the priors’ names are recorded in the city archives exactly as they always were since the constitution was first written. It is important to understand that all this is perfectly legal.

With uncanny good luck, Cosimo is elected gonfaloniere della giustizia, head of government, first immediately after his return from exile, then precisely as the heads of the Eastern Church arrive in Florence for their famous council of 1439, then again at a particularly tense moment in 1445. In short, he knows how to have his name pulled from the bag when it matters. But for the most part, Cosimo is careful to keep in the background, never to make a display of his unconstitutional power. “He mixed power with grace,” Machiavelli tells us in his Florentine Histories. “He covered it over with decency.” “And whenever he wished to achieve anything,” says Vespasiano da Bisticci, “to avoid envy he gave the impression, as far as was possible, that it was they who had suggested the thing, not he.”

Of course what the majority of people are suggesting to Cosimo is what kind of state or bank appointment they or their sons and grandsons and nephews would like to have. Begging letters pour in for positions that are supposedly chosen by lot. Cosimo does his best. But you can’t please everyone. The Councils of the People and of the Commune are not happy. Is this Florentine republicanism? After the Battle of Anghiari in 1440, the defeat of Milanese troops and the consequent elimination of the Albizzi threat to the regime, the pressure of public opinion is such that the traditional system of truly random elections has to be restored.

But only for three years. In 1444 the ten-year sentence of exile on Cosimo’s enemies is coming to an end. To have seventy old enemies return at once would be dangerous. So the councils are bullied into accepting a balia, thus once again temporarily conceding unlimited powers. The sentences of exile are extended for a further ten years. The electoral “experiments” resume.

In 1447 Visconti dies. With wonderful caprice, the duke bequeaths his title to Milan and all its territories not to Francesco Sforza, now married to his bastard daughter Bianca, but to Alfonso of Aragon, who had become king of Naples on defeating the Angevin family in 1442. Since the idea that the king of Naples in the extreme south should also possess Milan five hundred miles away in the far north was unthinkable to everybody except the man himself, the only possible reason for Visconti’s doing this must have been to cause a maximum of confusion and resentment. And in fact, the people of Milan immediately reject the duke’s will, rebel, and form a republic. The city’s many subject towns take the opportunity of the ensuing power vacuum to declare independence. The Neapolitans march north into Tuscany with the intention of taking what is “legally” theirs. The Venetians march west toward Milan to capitalize on the chaos. Furious, Francesco Sforza, who feels cheated out of his inheritance, joins the new republic in the fight to recapture its subject territories (and revenues) but then starts to claim them for himself whenever he is victorious.

Lombardy fragments. Over the next two years, all the major players will change sides at least once. So it is easy for the Medici regime to go on insisting that this is no time for erratic, randomly chosen governments. “The power of the accoppiatori was instituted to preserve the independence of Florence,” Cosimo declares. Meantime, two questions obsess the endless consultative bodies (Cosimo’s allies) poring over the electoral issue. First: Is a return to the constitutional system of random election ultimately inevitable to placate public opinion and republican sentiment? Second: If it is inevitable, can the reggimento, the status quo, somehow be guaranteed? “The greatest attention must be paid to the technical aspects,” announces Cosimo to one meeting. Whenever, in a democracy, we see our rulers obsessed with “the technical aspects” of the electoral process, whenever we see them tinkering with the size of constituencies, or machinery for counting ballots, then we know we are getting close to “the secret things of our town,” the gap between respectable appearance and brutal reality. It would be rare for a banker not to be present.

THROUGHOUT THE 1440S and 1450s, draconian balias are instituted, made semi-permanent, then suddenly dissolved in the face of angry public reaction. New scrutinies are compiled with new rules. How many name tags are to be put in which electoral bags? How many members of the same family can serve on the same commission? Some people get only one tag in one bag and some get many tags in many bags. Some people are taxed out of business and some are hardly touched. “Whoever keeps in with the Medici does well for themselves,” writes Alessandro Strozzi bitterly to his exiled brother-in-law. Again and again, the Councils of the People and of the Commune are presented with the most ambiguous legislation. They reject it. The signoria reformulates it. The regime is determined to follow the letter of the law, if rarely its spirit. The process is exhausting. Some of Cosimo’s allies are calling loudly for a more drastic and definitive solution. They’re losing patience. Why can’t we have complete control and be done? But Cosimo has long since understood—and this is his modernity—that since power can no longer stem from a truly legitimate source, but is always at the end of the day “seized,” it will always be at best ad hoc, pro tem. Any drastic and definitive solution would thus be a fort waiting to be stormed by someone else equally drastic and determined. It is better to appear to be in constant negotiation, constantly ready to compromise. In the end, the key thing is to keep people, if not actually happy, then happy enough. To keep the lid on.

The figure of the so-called veduto was important. When the podestà pulled a name from an electoral bag—for prior perhaps, or for one of the Twelve Good Men—the electoral officials had to check whether the person chosen wasn’t in some way barred from holding office. Had he paid his taxes? Had he, or a member of his family, served in a similar office within the last two years? Was he presently resident in Florence? Was he, or any of his relatives, already sitting on another council or commission? In the old days, when the election really was an honest lottery, many names might be pulled from the bag before one was eligible. To be pulled from the bag was to be veduto: “seen.” Actually to take office was to be seduto: “seated.” Since the results of the scrutinies that decided which names were in which bags were kept secret, to be veduto for the position of prior—or, better still, gonfaloniere della giustizia—was a great honor. It meant you had passed the tough selection procedure, you were a respected citizen. When new consultative commissions were convened, being a veduto was often a criterion of eligibility.

With the new form of “elections”—just ten names in each bag, rather than hundreds—there had been no veduti, or very few. People were disappointed. Resuming control of the elections in 1443, after a brief return to the constitutional procedure, the accoppiatori began to arrange matters so that there would be plenty of veduti, as if the election had been carried out in properly random fashion. In short, they had names pulled out of the hat, names they knew were ineligible, not in order to take office but to be veduti. The trick was painfully obvious, but people were pleased all the same. They received an honor and were not burdened with responsibility. Such is the special humiliation of the fake democracy: the invitation to participate in farce. We have all sensed it. Cosimo, in fact, is creating a new kind of public figure: the person who declares his belief in the fairness of the system because it offers him a small sop, a public recognition. It treats him as though he were an equal. Among the eight priors, most of them Medici men who had served over and over again on all kinds of powerful commissions, there would often be one fellow who knew he was there for the only time in his life. A special favor. He would spend around a hundred florins, more than a year’s salary perhaps, to buy the prior’s expensive gown of saturated crimson; he would be feted and congratulated by all his relatives. But for the two months of his “power,” he knew to ask no questions, nor to seek to influence decisions. From now on, he would always support the Medici. “Many were called to office,” wrote one commentator, “but few were chosen to govern.”

However secret the mechanisms by which the regime kept its grip on power, the results were now clear to everybody. A group of initiates from Cosimo’s inner circle was fixing everything. And growing richer. Foreign ambassadors did their business at Cosimo’s palazzo, rather than at the Palazzo della Signoria. The Milanese ambassador actually lived in Cosimo’s house. Every decision required Medici consent. The man is a prince in everything but name, thought the other leaders in Italy. But there is a great deal in a name. Why else would princes worry so much about their coronations? Despite analogies, the Florentine citizen’s condition was not quite the same as that of a subject in, say, the Papal States, or Milan. Equally powerless, he was mocked, or flattered, by the rhetoric of republicanism. He could not bow before his monarch in dignified fashion, saying, This is God’s will, nor, alternatively, tell himself: This man is a usurper and I only bow down because brute force obliges me to. Why did he bow down, then? At the end of the day, the Councils of the Commune and of the People did still exist. They could veto legislation. Under the Medici, the Florentine mind was constantly fired by ideals of political freedom that were forever frustrated. A fizz of excited political thought frothed over the submerged reality of protracted dictatorship. If the war ever came to an end, a domestic showdown was inevitable.

IN THE PAY of the newly formed Republic of Milan, Francesco Sforza was fighting Venice. He also received money from the Medici bank. But the people of Milan soon realized that the condottiere was actually planning to take the city for himself. To defend themselves against him, they made peace with the Venetians behind Sforza’s back. It wasn’t enough. Sforza besieged the town, cut off its food supplies, and starved it into surrender. Quite simply, he was the most powerful military phenomenon in the area. Cosimo then shocked both Florence and the rest of Italy by being the first to give this bastard upstart official recognition as duke of Milan. Did he do it to secure the large amounts of money the bank had lent Sforza? Many members of Cosimo’s own inner circle were angry and suspicious. Or was it because he honestly believed that further Venetian inroads into a weak Milanese republic would be a serious threat to Florence? Or for both reasons?

In any event, the Medici bank had already pulled its money and merchandise out of Venice before this momentous switch of alliances became known. There was nothing for the frustrated Venetians to seize in revenge. Outwitted, they sent agents to Florence to foment anti-Medici feeling. There was plenty of it. But when Venice allied itself with Naples for a joint attack on Florence and Milan, the Florentine people swung around behind Cosimo. The key to unity in Italy is always the presence of a common enemy. “Never did a winning faction remain united, except when a hostile faction was active,” says Machiavelli of the Florentines.

Ultimately, it was an enemy common to all of Italy that ended this new war just as it had begun to go rather badly for Florence. In May 1453, the Ottoman sultan Mehmet II captured Constantinople. Eastern Christendom had gone. At once the powerful Turks started to raid the Adriatic coast. It was a wake-up call of September 11 proportions. Time to stop quarreling. In 1454, the Peace of Lodi was signed and in 1455, with shameless rhetoric, a “Most Holy League” was declared, uniting Rome, Milan, Venice, Florence, and Naples against the Infidel. It thus turned out to have been a stroke of luck for Cosimo that the Greeks had been so stubborn about the nature of the Holy Spirit and found themselves alone against the tidal wave of Islam.

WITH THIS SUDDEN, unexpected peace, the political showdown in Florence could no longer be avoided. Their economy exhausted by the conflict, by another bout of the plague in 1448, and by an earthquake in 1453, many Florentines were starving. The councils insisted on a return to the old election by lot without the interference of the regime’s accoppiatori. No sooner had they got what they wanted than a more neutral, less pro-Medici signoria introduced a property tax that seriously threatened the interests of the rich. Cosimo put on a brave face and said he approved of the tax. It was important for him to have support from the lower orders. His fellow travelers were not so pleased. Prominent men were having to sell property to pay the tax. Still unsatisfied, the councils now also wanted a new, free, and fair scrutiny, which would mean more anti-Medici names in the electoral bags. What would happen if the government were really chosen at random after an impartial assessment of those qualified to serve? Where would the Medici be then?

Nervous, the regime seized on the chance of a favorable signoria to ask the councils to grant unlimited powers again. They would not. Since members of the councils cast their votes (actually beans) secretly, it was hard to twist their arms. When the legislation was sent back for the nth time, the priors demanded that votes be cast openly. The signoria’s two-month term of office was running out. At this point, Archbishop Antonino got involved on the councils’ side and threatened the regime’s bullies with excommunication if they tried to alter the constitution in this way. Perhaps precisely because the Church had taken so much money from the Medici, it felt the need to declare its independence. Voting in secret, the Council of the Commune and the Council of the People again rejected the proposed legislation. They were determined to bring rhetoric and reality together. Florence must be governed as the constitution stipulated. They wanted freedom.

This was the summer of 1458. As a last resort, the pro-Medici priors of the signoria decided to call a parliament, the first since 1434. Cosimo’s consent was sought and given. But first they waited until the Milanese ambassador had convinced Sforza to dispatch troops to Florence. With soldiers from Milan in place at all entrances to the piazza, the parliament went as parliaments must. Old, tired, and chronically ill, Cosimo was careful not to attend. A new, hundred-strong council was formed with complete power over all “matters of security.” It was a permanent balia, but without the dangerous name. From that point on, the pretense of legality was pure formality: a limited group of men would go on electing each other to this or that body without fear of interference. You could join in, but only if you were willing to toe the Medici line. Any real opposition would have to be armed. No one had the stomach for it. If this was a success for the regime, it was certainly a defeat for Cosimo, who had much preferred the pleasant façade, the collusion of grateful clients, the satisfaction of having persuaded people to do something that he had never openly requested. But the tools of persuasion that make such things possible today—our modern media, mass production, and mass consumption—were not available to the Medici. Nor had anybody thought of the trick of allowing two apparently opposing but secretly complicitous factions to rotate in power at the whim of a complacently “enfranchised” population. The strategy of the two-party democracy lay far away in the future. Meantime, Cosimo was growing more and more preoccupied with the prospect of life after death, and friends were becoming rivals.

At the Medici bank’s head office, Giovanni Benci was dead. Cosimo’s younger and favorite son, Giovanni, proved a poor replacement. He preferred the high life to the calculation of profit and loss. Immoderately fat, he bought himself a nice slave girl while serving as ambassador to the Curia in Rome. It was becoming a family tradition. Disappointed, Cosimo brought home the Geneva director, Francesco Sassetti, one of the world’s all-time great flatterers, to work beside his son. It was a sign the old banker was losing his grip. Sassetti wasn’t up to it. Having achieved his position through servility, he was incapable of imposing discipline. A branch was opened in Milan, but like the venture in Ancona years ago, it was mainly there to serve Sforza. There was very little serious trade in and out of Milan and hence little chance of profits from exchange deals. While a bank benefited an economy doing business—an economy such as Venice, for example—there was nothing it could do in Milan but encourage a duke to spend more than he ought.

Still, at least Italy was mostly at peace, and Cosimo was taking a lot of the credit for it. His astuteness, if it was that, lay not so much in his having switched Florence’s alliance from Venice to Milan as in having reduced the number of major players in the political game to match the number of states available. Anchored in Milan, Sforza was no longer a loose cannon, a military power without a state. Hence he no longer needed to fight to have an income. Cosimo hadn’t quite foreseen the consequences of this. He had expected Sforza would help Florence conquer Lucca in exchange for all the Medici money that had been showered on him in his struggle to become duke. Perversely, Sforza hung up his sword and settled down with wife and nineteen children, legitimate and otherwise, to enjoy his earthly possessions.

FREQUENTLY BEDRIDDEN, Cosimo no longer accepted public office. His sons, themselves middle-aged, were sick too. They all suffered from gout. When not away at their country estates, all three had to be carried around the huge palazzo they had built in town, among their beautiful collections and possessions. Cosimo cried in pain when he was lifted. There was a problem with urine retention. Taking a keen interest in Plato’s ideas about eternal life, paying generously for a new translation of the complete works of the philosopher, he now did most of his business in the windowless, candlelit chapel at the heart of the Palazzo Medici. On the walls, Gozzoli’s wonderful Journey of the Three Kings glimmered all around, showing Cosimo and his family beside the Magi, their donkeys carrying heavy merchandise across distant landscapes, rather as if bank and Bible had got mixed up. There was a monkey, too, sitting on a horse, and a cheetah. The bank occasionally dealt in exotic animals. Archbishop Antonino, who had not in the end excommunicated anyone over the 1458 coup, made a point of condemning supposedly sacred pictures that distracted the viewer’s attention with frivolities. He explicitly mentioned monkeys and cheetahs. Such is an established church’s opposition to the regime it lives with.

Cosimo heard mass. Above the altar, there was Lippi’s lovely painting of the Virgin and Child, plus a reliquary with genuine fragments from Our Lord’s passion. Hard to come by. And to make the man feel even safer, there was a secret tunnel to escape through—to be carried through, that is—should anyone ever have the nerve to try the frontal assault. It was in this tiny chapel that Cosimo received the men of the regime, to discuss “the secret things of our town.” It was in the chapel that Francesco Sforza’s son, Galeazzo, found him in 1459. Likewise, the marquis of Mantua’s son in 1461. On the second occasion, both Cosimo and Piero were in too much pain from their gout to give the youngster a tour of the great house. Only Giovanni was mobile. Limping heavily, his arm hanging on a servant’s neck, the obese man insisted he would oblige, but gave up when it came to tackling the stairs. Money and magic were impotent here. Moving goods all over Europe, the Medici men rarely made it to the top floor.

Giovanni died in 1463. Depressed, Cosimo knew he was next. Burial arrangements were carefully negotiated. No doubt money changed hands. He would lie beneath the very center of the nave of the Church of San Lorenzo, in close proximity to the relics of the holy martyrs. Above the sarcophagus, a stone column would connect it to the tomb-marker on the church floor, a large white porphyry circle enclosing two crossed oblongs, a magical motif signifying, apparently, eternity. The effect, when one visits San Lorenzo today, is both unobtrusive and absolutely central: the banker’s vocation. Barely noticed, he is the ground beneath the communicant’s feet. A last generous endowment paid for a mass to be said for Cosimo’s soul 365 days a year in perpetuity, and quality funeral clothes for all the mourners, including four female slaves. It is the only news we have of them.