THE NORTHEAST

Boston

On April 19, 1775, a force of 800 British infantrymen marched out of Boston to search and seize arms and ammunition at Concord 20 miles distant which had been gathered there by the “Minutemen” of the Massachusetts Militia. When they arrived at Lexington, Captain John Parker’s company of Minutemen blocked the way. No one is sure who fired “the shot heard around the world” on Lexington Green, but the British regulars soon scattered the American militiamen and arrived in Concord only to learn that the arms and ammunition had been hidden away. They also now became increasingly concerned by the presence of thousands of angry American militiamen gathering, who from the cover of trees, bluffs, and fences, began firing at them. The British troops turned back and by the time they reached Boston, 73 soldiers had been killed and 174 wounded. The Americans had lost 49 killed and 41 wounded. The decade-long political crisis between the 13 colonies and the mother country had evolved into war, one that would last for eight years.

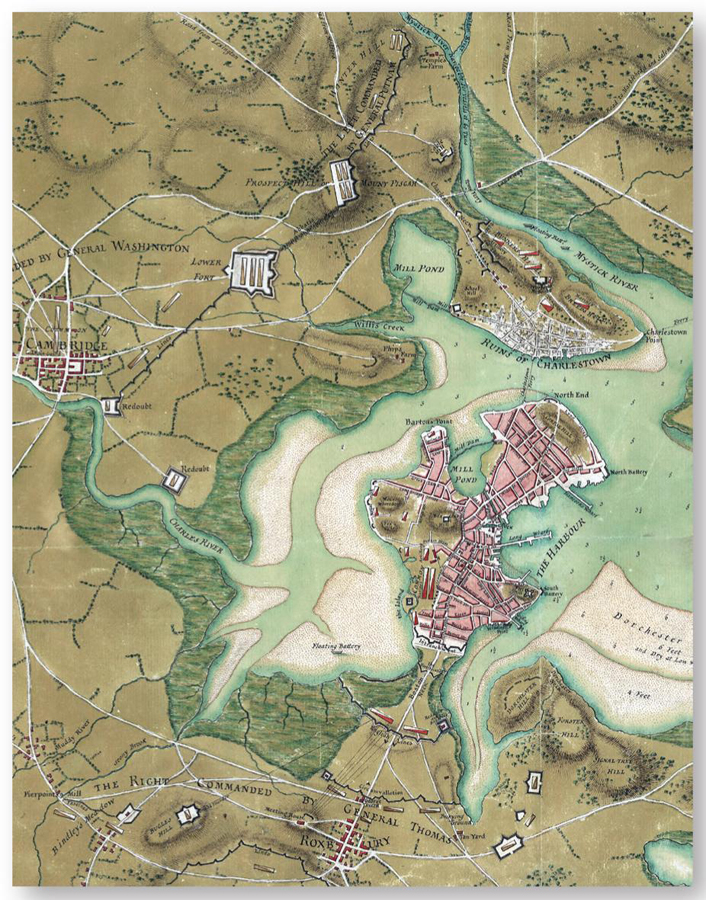

American and British fortifications and camps in and around Boston, 1775–76. The Americans built redoubts and defense lines mainly along the northwest and outside Roxbury near Boston Neck (at the bottom of this plan). The city (then occupied by the British) was sited on a peninsula accessible by Boston Neck that was protected by three lines of fortifications with a redoubt and batteries. Other redoubts were built on the western side, where most of the British troops were encamped. The older Fort Hill and the North Battery on the east side were meant to cover the harbor. This detail is from A Plan of the Town of Boston and its Environs… by Thomas Hyde Page, Royal Engineers. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington)

The American militiamen from the countryside surrounding Boston took up arms, mobilized for active service, and started digging trenches and building redoubts on the outskirts of the town so as to contain the British troops in the city. The Americans had few artillery pieces and were, in any event, reluctant to fire upon Boston and risk killing their own civilians. Up to that time, Boston had no fortifications save those to repel an attack from a seaborne enemy. The most important was Castle Williams on an island at the harbor’s entrance. The British secured Boston Neck, the sole overland access to the city, with three lines of entrenchments that faced the American “circumvallation” trenches just beyond Roxbury. The main British work in the city was a large earthen redoubt built on the summit of Beacon Hill. British reinforcements under generals Henry Clinton, John Burgoyne, and William Howe arrived in May bolstering the commander-in-chief General Thomas Gage’s forces to about 10,000 regulars in the city.

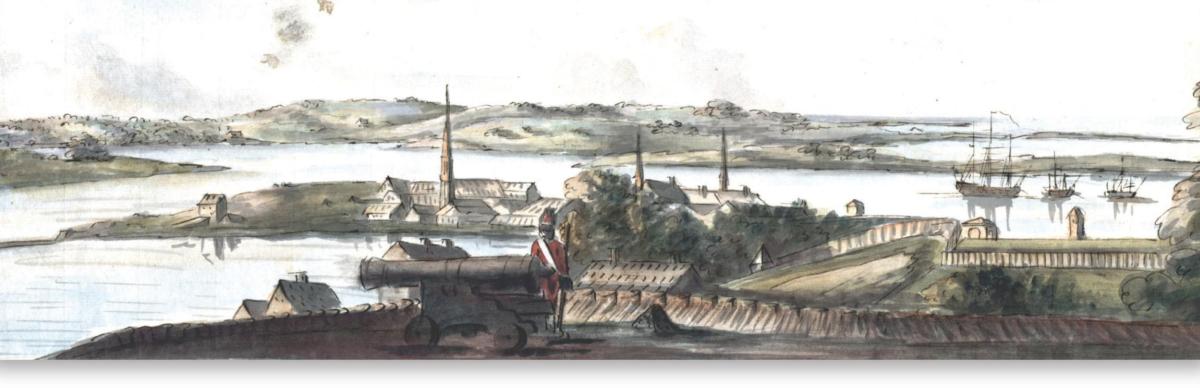

Interior of the British redoubt on Beacon Hill, Boston, 1775. This watercolor by Lieutenant Richard Williams, 23rd Fusiliers, shows a view to the north of the interior of the redoubt on Beacon Hill, one of the temporary fortifications built in Boston by the British Army in 1775. The parapet is made up of what seems to be barrels rather than gabions, testimony that trading had come to a standstill in Boston while besieged and blockaded by the American forces. The outer stockade and a sentry box are seen outside, the Mill Pond with its dam (at left) and the buildings on Prince and Snow streets. The surrounding hills occupied by the American forces are in the distance. (Courtesy Richard H. Brown Revolutionary War Map Collection; Boston Public Library)

By June, some 16,000 American patriot militiamen under Major-General Artemas Ward, the elderly commander of the Massachusetts Militia, were assembled outside Boston and were busy constructing field fortifications and redoubts at various spots to form a perimeter that would block any further British attempts to leave the city. An observer later reported:

lines of both [Roxbury and Cambridge] are impregnable; with forts (many of which are bombproof) and redoubts, supposing them to be all in a direction, are about twenty miles; the breastworks are of a proper height, and in many places seventeen feet in thickness; the trenches wide and deep in proportion, before which lay forked impediments; and many of the forts, in every respect, are perfectly ready for battle. The whole, in a word, the admiration of every spectator; for verily their fortifications appear to be the works of seven years, instead of about as many months.

For General Gage, it was important to secure the neighboring hills, especially those of Charlestown to the north and of Dorchester to the southeast. Dorchester was somewhat isolated and would require either traversing the American lines and redoubts at Roxbury, then turning east, or crossing by boat; both ways were likely to be difficult, with the added risk of being outflanked by numerous American reinforcements. By contrast, Charlestown was easily accessible by boat from Boston and, up to the evening of June 16, its heights were not occupied by the Americans. On the morning of June 17, General Gage and his officers observed considerable construction activity on Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill, just behind Charlestown, which was situated on a peninsula accessible by the narrow Charlestown Neck between Mill Pound and the Mystic River. It was decided to clear the “Rebels” out of that peninsula and secure Bunker Hill and especially Breed’s Hill, where a substantial redoubt was being built.

The American army outside Boston did not have specialized corps such as military engineers, but it did have experienced and knowledgable individuals in elements of artillery, which encompassed many aspects of engineering. The most famous example was the Boston bookseller John Knox, acknowledged ordnance expert on account of his wide reading in the subject, who became the chief gunner in the Continental Army. Some of the older Massachusetts Militia officers had also seen active service during the Seven Years War; the art of digging trenches and erecting redoubts was therefore familiar to them. The above factors explain why the field fortifications built on the outskirts of Boston clearly assumed professional designs such as those found in military manuals. The Americans also knew the main weakness of their force: it could only fight behind cover in a fortified position, given that it was a gathering of militiamen, not of a professional army drilled for months in the intricacies of battalion movements to march in perfect lines under enemy fire as practiced by European armies. It was thus important for the Americans to be familiar with the basics of fortification, and they were.

To secure the Charlestown peninsula area, Gage gathered a force of 3,000 men. Everyone in the British contingent was highly optimistic and it was practically taken for granted that the mob of “rebel peasants” would soon be scattered by infantry and naval bombardments. It was a case of gross overconfidence, however. North-American farmers were different to their European counterparts in that most owned their farms and, in line with colonial militia laws, were required to own muskets that many of them used for hunting – some being quite skilled at target shooting. Unlike the European “peasantry,” a substantial proportion of American men were armed and familiar with the basics of military organization as enrolled militiamen. In spite of the previous retreat from Lexington and the fact that hordes of armed Americans blockaded the city and built many field fortifications, the British officers do not seem to have taken the above factors fully into account.

Breed’s Hill and Bunker Hill

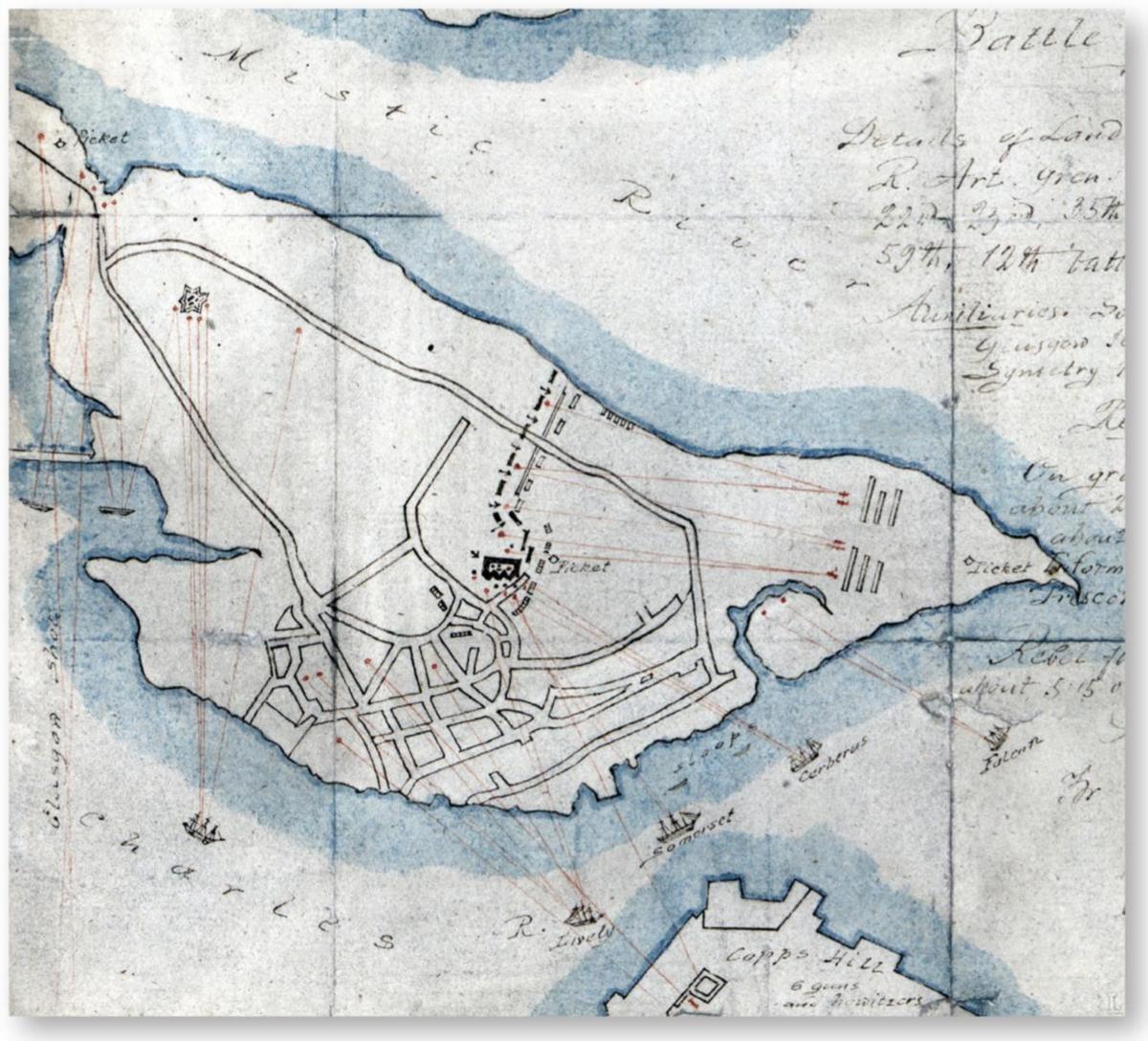

General Gage could have easily cut off the 2,000 men laboring on the hills of the peninsula by seizing Charlestown Neck. The Americans were intent on building a large redoubt on Bunker Hill to the north, near the Neck, so as to provide some protection to this access route, but that instruction was misunderstood and most efforts went into fortifying Breed’s Hill instead. The earth redoubt was about 40 yards square with 6ft-high parapets mounted with wooden gun platforms; “In the only side on which it could be attacked were two pieces of cannon. In the two salient angles were two trees, with their branches projecting off the parapet, to prevent an entry being made on the angles” (Gentlemen’s Magazine). Also constructed was a defensive line of earth and stone with a two-rail wooden fence on top complimented by three flèches, running between the Breed’s Hill Redoubt and the Mystic River, to cover their left flank. By early afternoon of June 17, the British infantry had landed on the southern end of the peninsula and were forming battle lines. Gage had made the decision simply to attack the American positions at Breed’s Hill and along the rail-fence line. In all likelihood, according to Gage, the Americans would break and run away at the sight of the approaching troops; Lexington would be avenged and the rebellion crushed in a matter of hours.

“Plan of the Battle of Bunker Hill,” which occurred on June 17, 1775. This plan is especially interesting since it was signed by Major-General Henry Clinton and dated October 4, 1775 as an addition to his earlier report of June 18 on the battle. It is thus probably one of the most accurate showing the event. It shows the large American redoubt on Breed’s Hill and the trench line from this to the Mystic River bombarded and attacked by British troops. Also shown at left is the starshaped American redoubt on Bunker Hill being bombarded by British ships. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington)

The British line advanced in perfect order simultaneously against the redoubt and the rail-fence. Instead of fleeing, the Americans kept their cool and waited until the British were about 50 yards away. Then they fired a tremendous volley; the whole front rank of British soldiers was hit and went down. Their comrades returned an ineffective fire against the entrenched Americans and, after a few minutes of further casualties, they broke ranks and ran down the hill. The astounded British commanders paused and rallied their men while the exultant Americans cheered. At this time, fire broke out in Charlestown following the bombardment of British ships, and rapidly spread; some 400 buildings were destroyed. The reason for Charlestown’s destruction may have been to create a smoke screen for a separate attack, but it did not succeed since a light breeze drove the smoke away from the American entrenchments. At length, a second assault was attempted. Again, the battalions marched up the hill, again the American volleys decimated their ranks; after a short struggle, the British troops retreated once more in disorder, leaving the slopes covered with dead and wounded red-coated soldiers. British casualties were high, while those of the well-protected Americans were, thus far, minimal.

The British assault on Breed’s Hill, June 17, 1775. This 1786 painting is one of Trumbull’s early versions. Some of the men shown were actual likenesses. The fatally wounded American Dr Joseph Warren, lying on the ground, is saved by Major Small from being bayoneted by a grenadier while stepping over the fallen Colonel James Abercrombie. The wounded Major John Pitcairn of the Marines, behind Small, is being taken away. American General Israel Putnam is at the far right. British generals William Howe (wearing a hat) and Henry Clinton are brandishing swords in the background near their flag. (Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery, New London, CT)

However, the defenders of Breed’s Hill and the rail-fence were running out of ammunition. Furthermore, all was confusion in Major-General Ward’s American command further away; the lack of experience in staff work meant that reinforcements and a resupply of ammunition were not forthcoming. At about 5.00pm, the British troops began marching up the hill for a third assault. The Americans fired again and the advancing British columns were shaken, but the defenders’ shooting now became more sporadic as they ran out of powder. Seeing this, the British soldiers charged and at last managed to enter the Breed’s Hill Redoubt and overcome the fence-rail. Their bayonets slaughtered many Americans, but the latter managed an orderly retreat across Charlestown Neck while the British occupied the other redoubt on Bunker Hill and did not dare go further than the peninsula. It had been a bloody fight by any standard: the British had 1,054 killed and wounded (one soldier in every three deployed, and one in every two engaged), while the Americans had suffered 449 casualties, mostly during the last assault (around a quarter of their force). The British held the ground, but it can be seen as more of an American victory. The “rebels” proved to be brave and resilient fighters when sheltered by good field fortifications which were erected with remarkable speed. Such works could be built quickly and almost anywhere, and the battle of Bunker Hill, as this engagement became known, showed that the American troops could defend their fortified positions with an efficiency that their opponents never suspected.

A THE BRITISH ASSAULT ON BREED’S HILL, JUNE 17, 1775

As explained in the main text, the “Battle of Bunker Hill” was fought at Breed’s Hill. Due to some confusion, the redoubt built by the Americans during the night of June 16/17 was actually erected on Breed’s Hill, a lower eminence of Bunker Hill, and its artillery emplacements were protected by 6ft-high works. Later reports spoke of Bunker Hill and the battle is remembered and commemorated by that name. It has been suggested that gabions were used in these works, but artist John Trumbull watched the battle from the opposite side of the harbor and, in the many paintings of the battle that he made over the next four decades, simply showed mostly earthen works that would have been reinforced with timber although not always visible. Gabions might have been used in limited quantity, but one has to wonder if any would have been made by American patriot militiamen, who were then basically still armed civilians, as early as June 1775. On the night of June 16/17, just getting earth walls up before dawn was the priority and there was certainly no time for the Americans to revet the works with grass or boards. Thus, the earth and pebble appearance given by Trumbull is surely what he saw from afar. At Breed’s Hill, the redoubt could give enough cover for the patriots lining the walls to offer good protection while shooting on the advancing ranks of British soldiers. This is the moment shown. It was only when the Americans ran out of ammunition that the British troops at last succeeded in taking the American works. British casualties were very high, proof that Americans could stubbornly hold a simple and hastily built field fortification and wreak havoc.

Ticonderoga’s guns

On the night of May 10, 1775, the small garrison of Fort Ticonderoga was fast asleep when the sentry was startled by knocking at its gate; a messenger had just arrived with an important note for Captain William Delaplace who, once awake, had the gate opened. In an instant, some 160 armed American patriots rushed in and overcame the two officers and 48 soldiers of the British 26th Regiment of Foot. Originally built by the French from 1755, the fort (which had been partly destroyed, and then repaired by the British) contained a large quantity of ordnance, including heavy guns. Several days later, the nine soldiers detached at Crown Point on the southern end of Lake Champlain also surrendered. The capture by the patriots of these weakly garrisoned forts, especially Ticonderoga, was to have major strategic consequences.

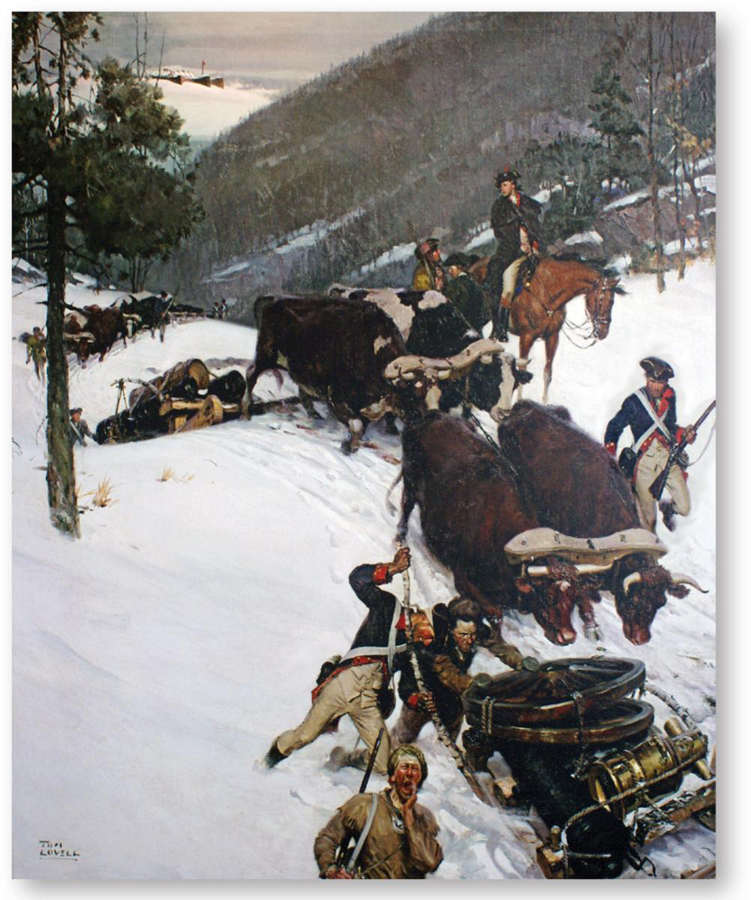

In June, George Washington, a Virginia officer who had distinguished himself during the campaigns of the Seven Years War, was appointed by Congress to the role of commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, which he joined at Boston in early July. Many of the men in his army now wished to return home to attend to their farms and businesses upon the expiry of their short-term enlistments, but enough remained to maintain an effective blockade around Boston. After Bunker Hill, the British were not keen to attack American lines and redoubts; months of sporadic skirmishing passed while Washington sought to break the deadlock. His army had little artillery and ammunition, but the recent capture of Fort Ticonderoga, replete with ordnance, could change that. Henry Knox was sent to the fort and, from December 1775 to early March 1776, about 60 heavy cannons and mortars with ammunition were hauled and dragged across rivers and snow-covered mountains for some 300 miles until they finally reached the American lines outside Boston.

General Washington and his officers wanted to end the siege’s deadlock by occupying Dorchester Heights and building batteries of heavy artillery there; this position commanded the harbor and city of Boston even more effectively than the Charlestown Peninsula. On the night of March 4, some 1,200 American troops suddenly moved in and started work on substantial fortifications in the darkness, their noise being covered by an all-night cannonade initiated by the Americans to fool the British. Since the ground was still frozen, it could not be dug. Occasional engineer Rufus Putman came up with a solution seen in a borrowed copy of Muller’s Field Engineer: making “chandeliers” whose timber frames were laid over the ground and filled with earth and other material such as “a vast number of large bundles of screwed hay” brought by some 360 oxcarts. These works were strengthened, notably with “a great number of barrels, filled with stones and sand, arranged in front of our works; which are to be put in motion and made to roll down the hill, to break the ranks and legs of the assailants as they advance,” recalled James Tatcher. By early morning, the dismayed British in Boston could clearly see artillery positions on Dorchester Heights that had been, when last seen the evening before, grass-covered pasture.

The “Noble Train of Artillery,” December 1775 – a painting by Tom Lovell. The American surprise capture of Fort Ticonderoga on May 10, 1775, included its numerous pieces of heavy artillery. From December 1775 to the end of January 1776, American artillery commander Henry Knox managed to have some 60 tons of ordnance hauled in an epic journey to General George Washington’s army blockading the British troops in Boston. By early March, American batteries around Boston had the heavy guns. As a result, the British evacuated the city on March 17. (Joseph Dixon Crucible Company, Jersey City, NJ/Fort Ticonderoga Museum, Ticonderoga, NY; author’s photograph)

Bombardment would soon make Boston untenable and General Gage ordered Lord Percy to attack Dorchester Heights with 3,000 men at once. However, nature also intervened in the form of a heavy storm that made crossing the army by boat impossible. By March 5, it was clear that the Americans had made the earth and timber fortifications almost impregnable. Howe cancelled the order to attack and concluded that the only way to save his army was to evacuate Boston. He advised the Americans not to intervene or he would destroy the city; Washington’s gamble with Ticonderoga’s guns, which had not even fired a round, and making Dorchester Heights’ earth and timber fortifications formidable paid off handsomely and an armistice was agreed. On March 17, some 12,000 soldiers, Loyalists and their dependents sailed out of Boston after dismantling old Castle William, which guarded the harbor’s access.

The fortifications of New York and Manhattan, 1776–83

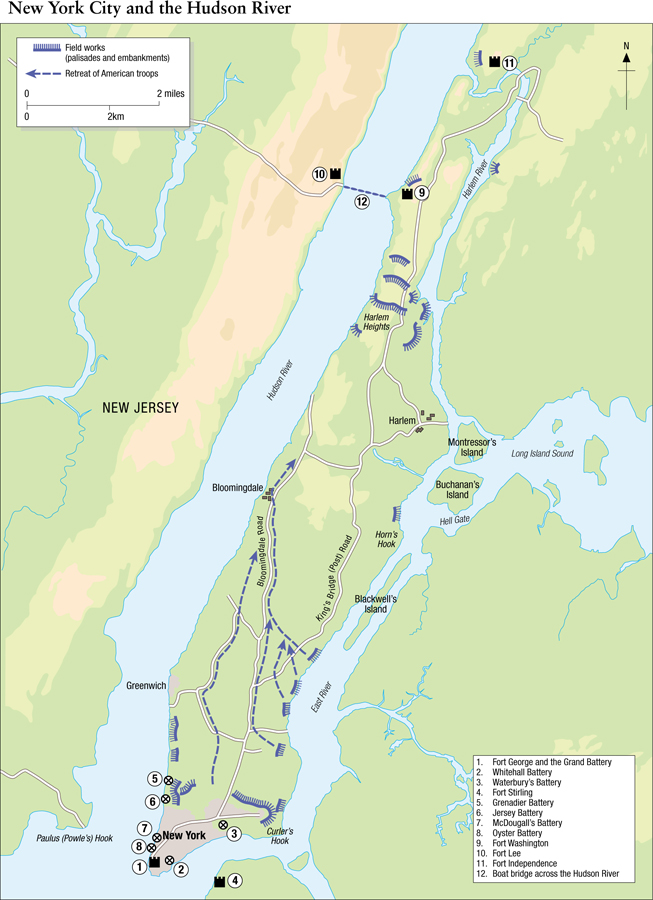

The British fleet that evacuated Boston in late March 1776 went to Halifax. By that time, the British government had made arrangements to send more troops and ships to North America while it reaffirmed its policy of subduing the rebellion. New regiments were raised, Loyalists were armed, and German mercenary troops hired. In July, a large British fleet with about 32,000 troops led by General Sir William Howe on board anchored in lower New York Bay. The British objective was to occupy New York City and control the Hudson River Valley. Howe’s troops were landed on Long Island and, on August 26, defeated the weaker Continental Army under General Washington, who averted annihilation by withdrawing north to forts Lee and Washington in the Harlem Heights area. In mid-September, the Americans evacuated New York City – its old Fort George, with a few shore and island batteries, being easily vulnerable to a force such as General Howe’s. Because of its excellent strategic position, New York City became the headquarters of the British forces in North America; henceforth, a substantial number of army troops and Royal Navy ships would always be stationed on Manhattan Island and in its immediate area. Furthermore, many field fortifications were built by the British and German troops, especially just around the Harlem Heights area.

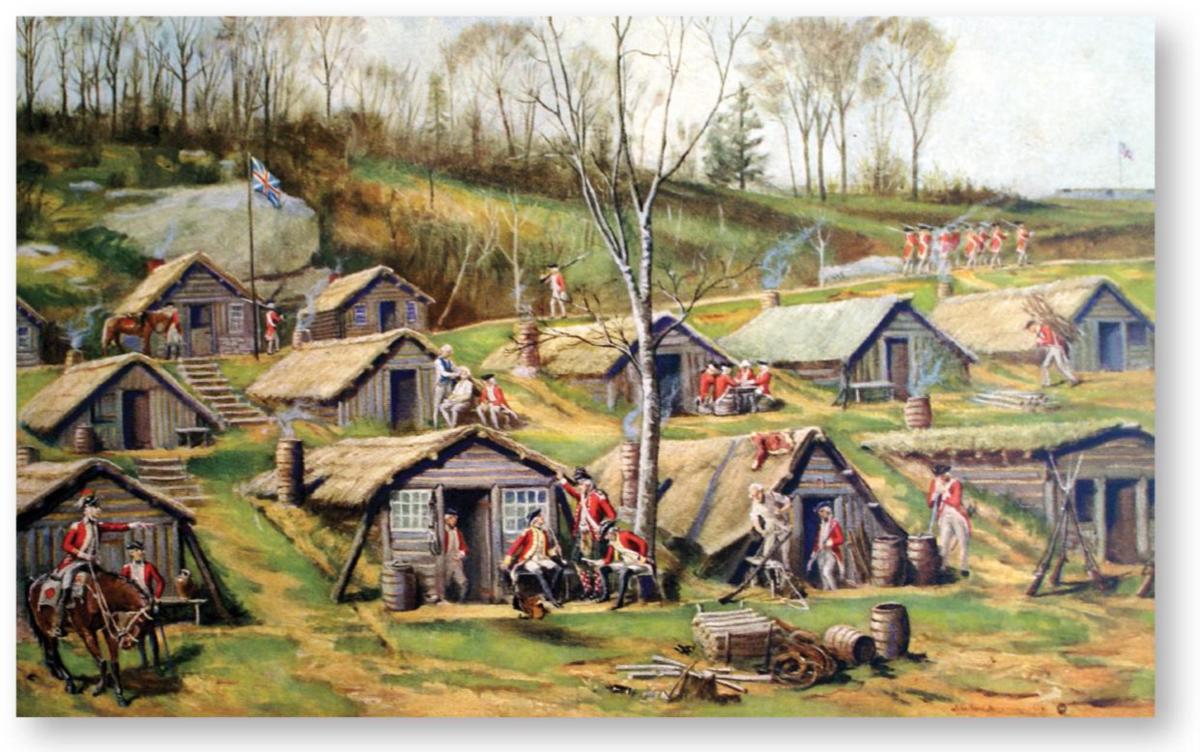

A British hut camp on the outskirts of New York City, c.1776–83, in a print after J. W. Dunsmore in R. P. Bolton’s Relics of the Revolution … on Manhattan Island (1916). The camp shown here was at Dunmore Farm in northern Manhattan. (Author’s collection)

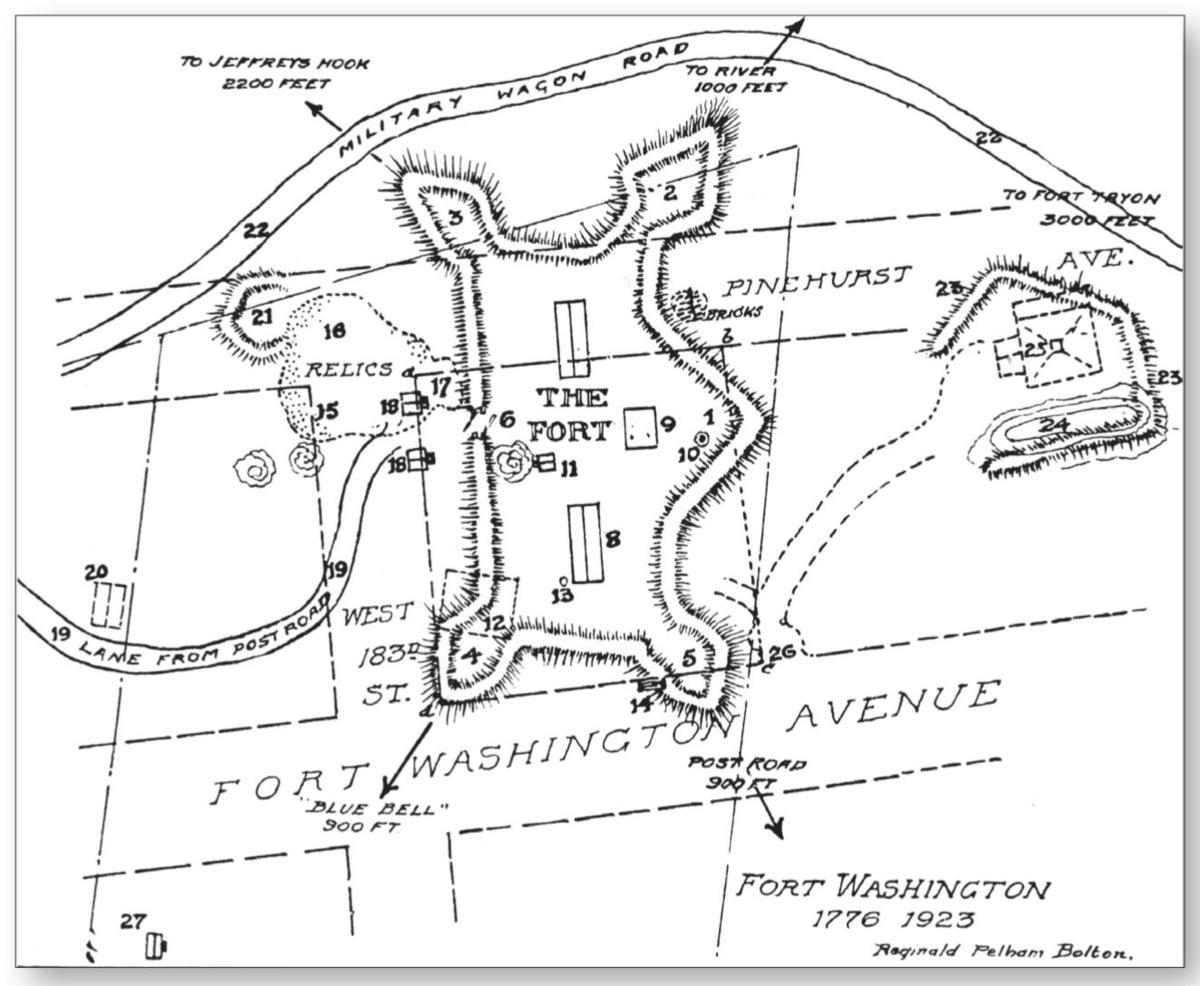

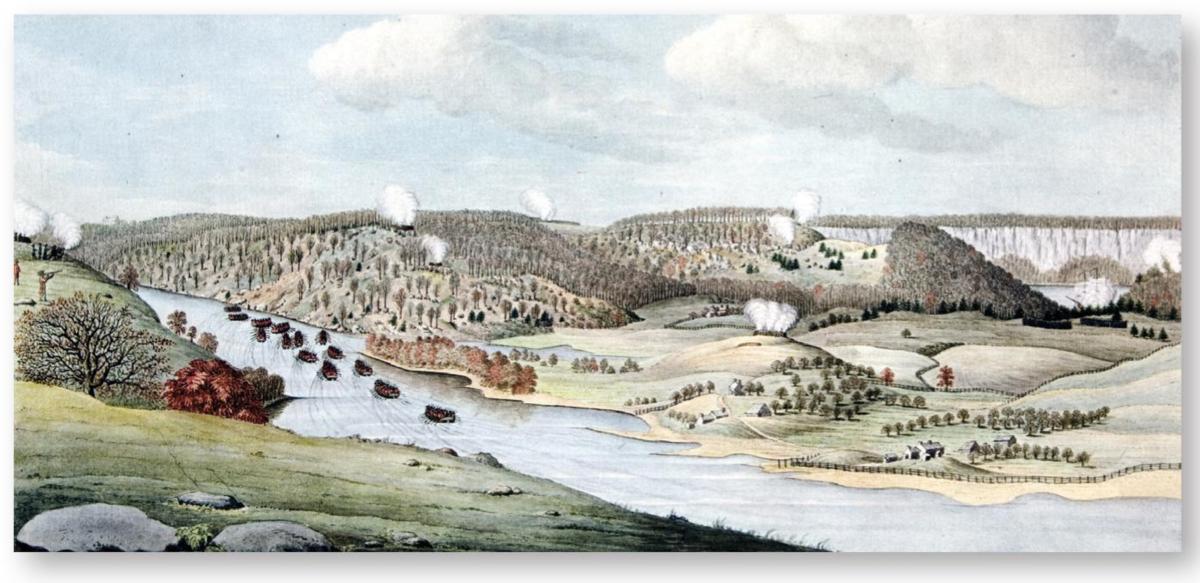

The Americans dug in too. They were determined not to allow the British to gain control of the Hudson River Valley. Fort Washington, to the north of Harlem Heights, was a large, bastioned earth and wood structure built on a rectangular plan on an eminence overlooking the Hudson River. Just across the Hudson River on the New Jersey shore was Fort Lee; both forts were connected by a boat bridge that also served to block the passage of shipping north on the river. On October 9, two British frigates broke through the boat bridge, proving the Americans could not bar the passage. Three days later, General Howe bypassed the northern end of Manhattan, eventually chasing Washington’s troops as far as White Plains (also known as Chatterton’s Hill) where he lost about 230 British soldiers before taking American entrenchments. Howe then turned south, detached part of his troops on the New Jersey shore, and moved on to forts Washington and Lee. Fort Washington was the main American work and about 3,000 men were posted there. It remained, however, unfinished, having no outer defenses (other than isolated redoubts), deep ditches, or ravelins; it was thus actually a weak citadel armed with 34 cannons and two howitzers. Several redoubts were located in the area around the fort, notably to the south, the most vulnerable side for an infantry assault. Sensing it could not resist, General Washington had asked for the fort to be evacuated, but General Nathanael Greene delayed and, by November 15, it was too late. Howe’s superior army assisted by Royal Navy warships invested the place and, the following day, British and German troops mounted a general assault under the command of General Wilhelm von Knyphausen. At length, the latter succeeded in overcoming the stubborn resistance of the garrison. Once again, Americans protected by field works inflicted some 500 casualties on the attackers, compared to their own losses of about 150; however, over 3,000 Americans were made prisoner. Regrettably, some enraged German soldiers slaughtered a few prisoners before they could be stopped; it is said that General Washington was watching from the opposite shore and wept when he saw the slaughter. As a result of the fall of Fort Washington, Fort Lee across the river was evacuated. The Americans thus suffered a major setback and the British now controlled the lower Hudson River Valley.

An outline of Fort Washington, 1776–83, from W. L. Carver and R. P. Bolton’s History Written with Pick and Shovel (1950). Built by the Americans at the northern end of Manhattan Island, it was captured by British and Hessian troops and renamed Fort Knyphausen. This map was based on archaeological surveys made in the early 20th century. (Author’s collection)

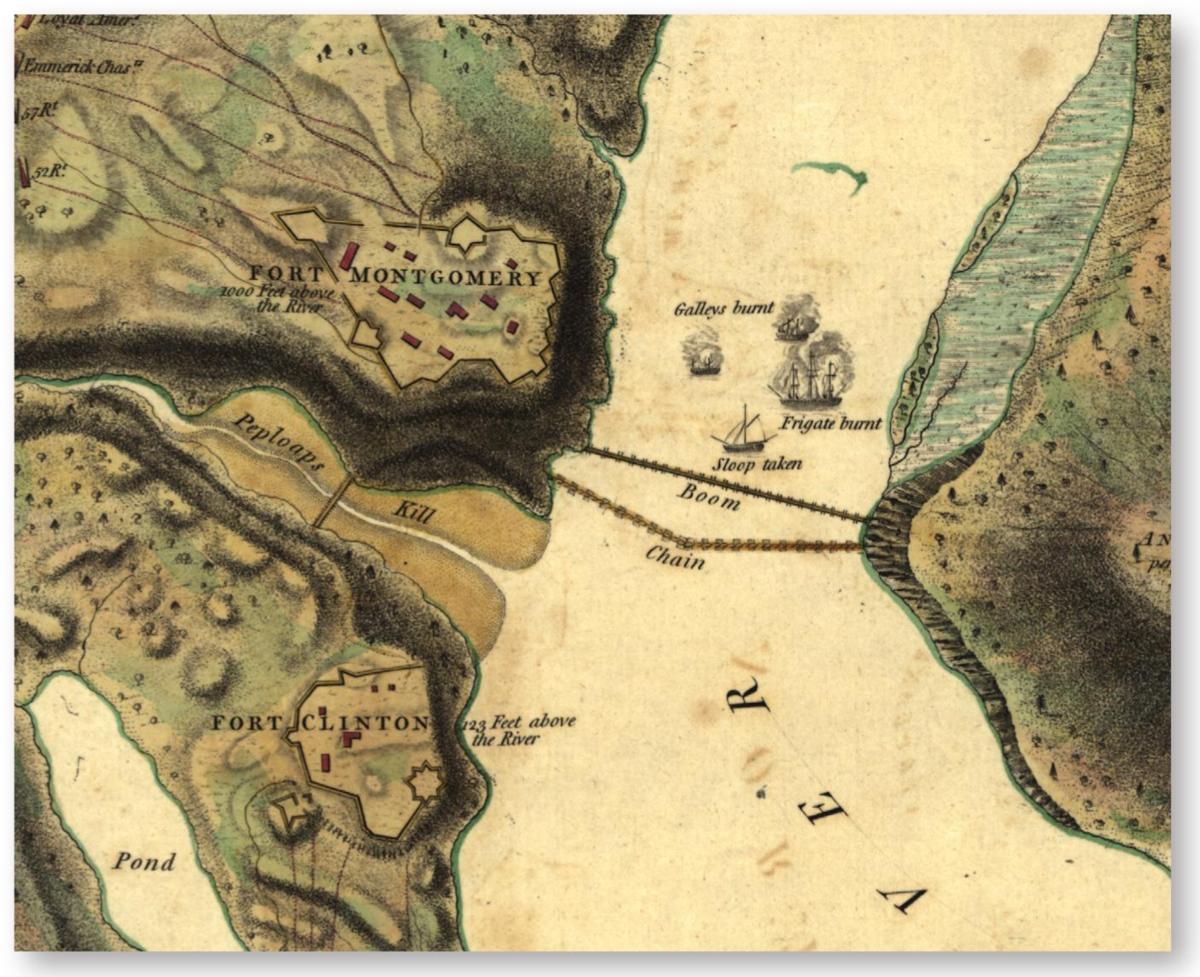

The American forces retreated further north and built forts Clinton and Montgomery on high ground bordering the west bank of the Hudson about 40 miles from New York City. They also laid a chain across the river. Of these earthen forts reinforced with timber and stone, Fort Montgomery, built on a triangular plan, was both the most extensive and impressive, being situated on a 1,000ft-high cliff. The forts were still under construction when, on October 3, 1777, Sir Henry Clinton leading 3,000 British and German troops headed north. He secured Stoney Point early on October 6 and proceeded to attack and take both American forts from the landward side. The forts were then destroyed. Sir Henry’s troops went as far as Kingston along the Hudson, ravaging towns along the way, but then turned back seeing that many more American troops were mobilizing to surround his force. Thus vanished the last British hope of putting pressure on the southern flank of General Gates’ American army that was closing in on General John Burgoyne’s British and German army trapped at Saratoga (see later).

A View of the Attack against Fort Washington and Rebel Redoubts near New York on the 16 of November 1776 by the British and Hessian Brigades, a watercolor after Thomas Davies. Fort Washington is the long narrow rectangle on top of the hill at the center of the picture. The outlying redoubts are also shown with smoke arising from them. (Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery, New London, CT)

The Americans regrouped and, in January 1778, established their Hudson Highlands stronghold at West Point, a natural fortress with an imposing cliff overlooking the western shore of the Hudson River 55 miles north of New York City. Here they built a new fort (initially called Arnold and later changed to Clinton) whose landward southern and western earthen curtain walls were 9ft high and 20ft thick with bases revetted with stone. There were also three redoubts and batteries to the south named forts Meigs, Wyllys, and Webb along with Fort Putman and Rocky Hill, a strong outer redoubt. The Shelburne redoubt was west of Fort Clinton. Across the river were three batteries to the north and, further inland to the southeast, the North and the South redoubts. A floating boat bridge linked both shores. An important feature was a chain laid across the river, and further obstacles were placed in the water to prevent uncontrolled navigation. West Point was also home to the Continental Army’s engineering school, as well as warehouses, making it a major supply center for the American army. These works were designed by Louis de la Radière and completed by Tadeusz Kosciuszko, both of whom had studied engineering in France before being commissioned in the Continental Army.

The “eagle’s nest” location of Fort Putnam, one of the southern defenses of West Point, is clearly shown in this detail of an 1825 painting by Thomas Cole of the fort’s substantial ruins. (Philadelphia Museum of Fine Art; author’s photograph)

In late May 1779, Sir Henry Clinton again exited New York City with about 6,000 men hoping to secure the Hudson Highlands. In early June, his force occupied Stoney Point, whose 40-man American garrison set fire to their blockhouse before fleeing north. The British built an earth fortification with outer abatis on a rocky height only vulnerable from the west and armed it with 15 pieces of ordnance. Failing to goad General Washington into a general engagement, the British returned to New York leaving about 650 men to garrison Stoney Point. Washington then ordered General Anthony Wayne to capture it. On July 15, he marched down from West Point towards his objective with 1,300 men. The work built on a rocky height was protected by the Hudson River to the east, north, and south, and by swamps to the west. It was taken by a well-executed, surprise bayonet assault after midnight on July 16. Lieutenant-Colonel François Fleury, an occasional engineer and also battalion commander, was the first man to enter the enemy works, sword in hand, and he boldly pulled down the British flag. Its capture provided great encouragement to American morale and was widely reported upon, although it was abandoned two days later because Washington did not have enough troops. It was reoccupied and strengthened by the British, but its importance was diminished.

“View of the British Fortress at Stoney-Point [New York], stormed and carried by a party of the Light Corps of the American Army, under the command of Gen. WAYNE, on the Morning of 16th of July last [1779].” This crude print, published in 1779, is one of the rare American renderings showing an assault on a fortified position. The marker A denotes “The British fortress.” The reserve is shown at bottom left, while the “detached Party who stormed the Works” can be seen above them. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington)

The British, too, were short of men in New York. An American raid took place before dawn on August 19 on the British redoubts at Paulus (Powle’s) Hook (now Jersey City) just across from New York City. Major Henry Lee made a surprise bayonet attack over the abatis and ditch, took its two redoubts – each of which had a blockhouse – without a shot, and immediately withdrew with 158 prisoners. In the fall of 1779, the positions they had taken from the Americans at the northern end of Manhattan and the heights bordering the eastern shore of the East River were evacuated by the British, who demolished all fortifications above a new defensive “line of circumvallation” built across the island. Thereafter, the tactical situation in the New York area remained at a standstill since the main focus of the war had moved from the northern to the middle and southern states.

American General Benedict Arnold boards the Royal Navy sloop HMS Vulture on September 24, 1780, fleeing from the consequences of his failed attempt to deliver the United States’ fortress at West Point to the British forces. When the plot was discovered, Arnold escaped to the Hudson River, and took refuge on the British ship. He later served as a general against his compatriots, earning for himself universal and ongoing scorn as a traitor to all Americans. A print after Howard Pyle. (Author’s collection)

Although the British could not take formidable West Point by the sword, they tried to do so by treachery. In July 1780, the leading American general Benedict Arnold, embittered by a perceived lack of recognition, proposed to betray his command, West Point, and his substantial garrison to the British. However, on September 23, the plot was discovered when a civilian, revealed to be British Major John André, was stopped by American militiamen and found to be in possession of compromising documents. Arnold managed to escape, André was hung as a spy, and the “American Gibraltar” was saved.

Plans of forts Montgomery and Clinton, 1777 – a detail from a map by John Hill. These American forts were taken by the British on October 6. Both consisted of earth and timber walls built on irregular plans, and featured an inside redoubt. Fort Montgomery was built on a cliff 1,000ft above the Hudson River; Fort Clinton was much lower at 123ft elevation. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington)

The result was that some 10,000 British regular troops remained isolated in the area of New York City and its immediate outer areas. Protecting the most strategically important British military base in North America remained crucial. A strong garrison was necessary since New York was permanently surrounded by at least a dozen Continental Army regiments assisted by cavalry, artillery, and, at times, militia regiments. There was also an internal security worry since it was suspected that a substantial part of the population was sympathetic to the American case.

The Mohawk Valley and Saratoga

In 1777, General Sir John Burgoyne was to carry out a grand plan to crush the rebellion in New York and adjacent states accompanied by the utter defeat and ruin of the Continental Army. He would personally lead an 8,000-man army south from Canada; a secondary force of 2,000 men would approach from the west and secure the Mohawk River Valley; General Sir William Howe would come up the Hudson from New York. The meeting point was Albany. The details of the utter failure of the plan and its disastrous consequences for the British cause regarding American independence, which had been proclaimed since July 4, 1776, are well known. Here we shall focus on the role of fortification in what amounted to three separate campaigns.

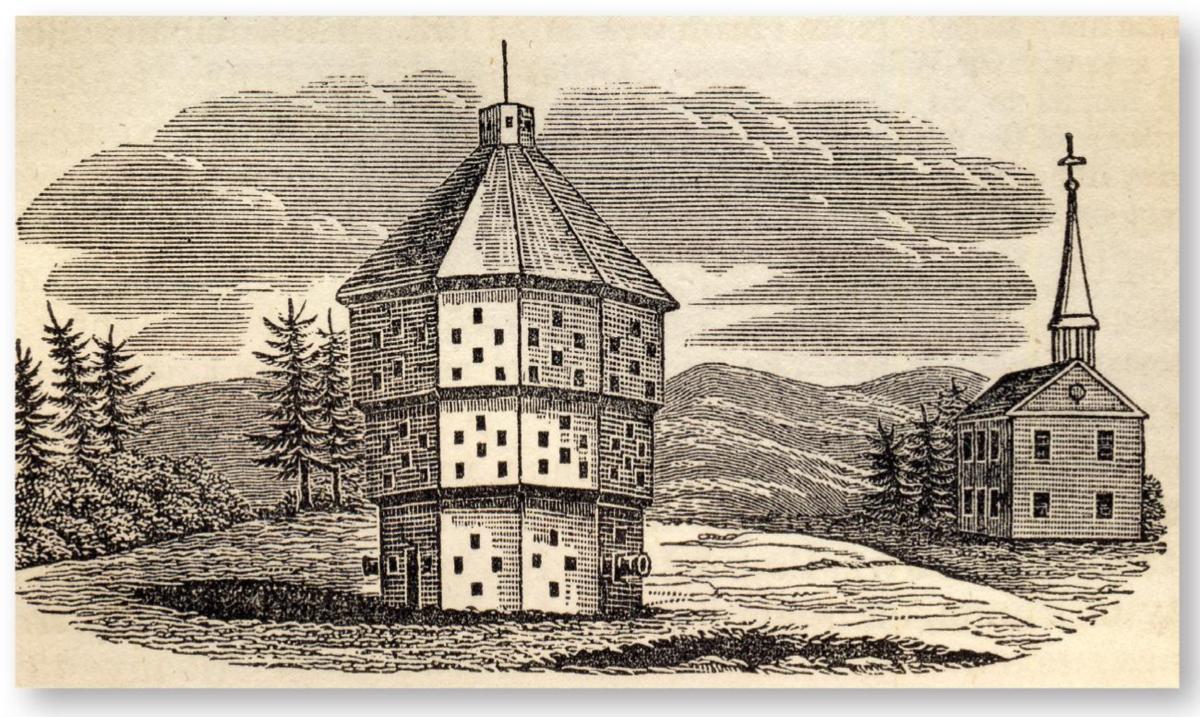

Blockhouse at Fort Plain, NY, c.1776. Built in 1776 to protect the village of Fort Plain on the northern shore of the Mohawk River against Indian and Loyalist attacks. According to J. W. Barber and H. Howe’s Historical Collections… (1845), its “form was an octagon, having portholes for heavy ordnance and muskets on every side. It contained three stories or apartments. The first story was thirty feet in diameter; the second, forty feet; the third, fifty feet; the last two stories projecting five feet … It was constructed throughout of hew timber about fifteen inches square; and besides the port-holes aforesaid, the second and third stories had perpendicular port-holes.” (Author’s collection)

Howe, seemingly through a lack of effective communication, headed south from New York City with 15,000 troops in late July 1777 to attack Philadelphia instead of going north. When, in early October, General Sir Henry Clinton moved north from New York City, it was too little and too late.

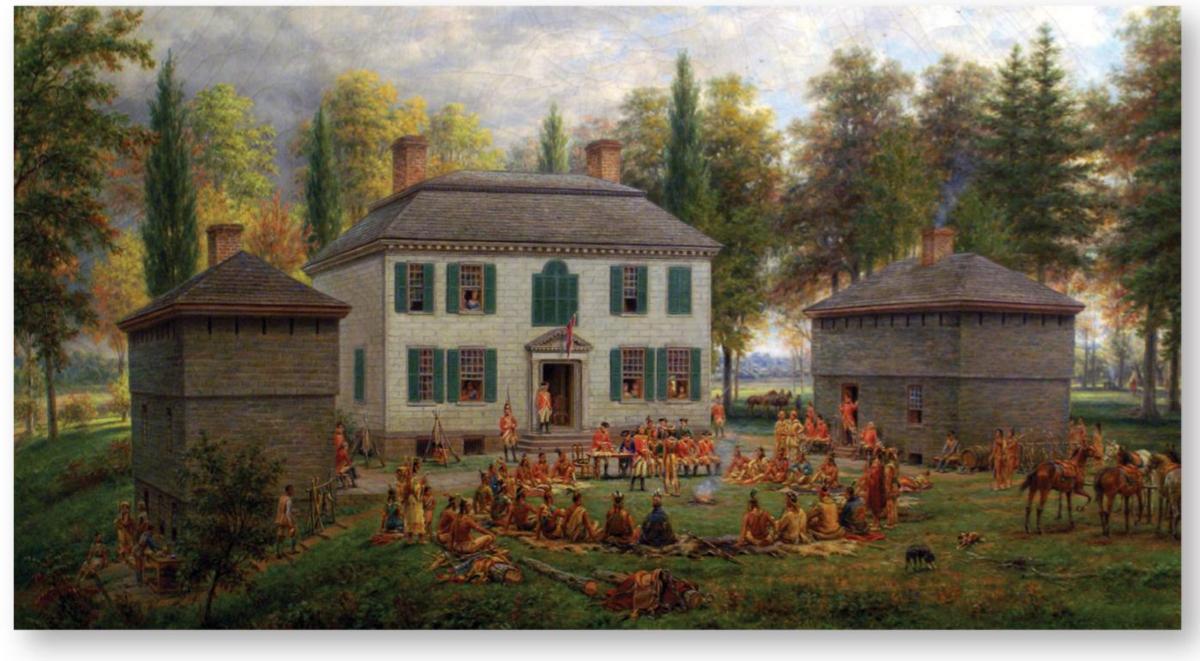

At Oswego, Lieutenant-Colonel Barry St Leger commanded a force of some 1,700 mostly Loyalist troops that included several hundred Mohawk warriors led by Chief Joseph Brant, all of which reached Fort Stanwix (that had been renamed Fort Schuyler, now Rome, NY) on the north shore of the Mohawk River on August 3. This was a large earth and timber fort built since 1758 on a square plan with bastions. It had a garrison of 750 American troops under the command of Colonel Peter Gansevoort. The British simply had to take this imposing work in order to proceed east towards Albany. As it was, communities along the Mohawk River were solidly loyal to the American cause and had already often suffered from raiding parties of British Loyalists and Mohawk Indians, the latter largely at the behest of Sir John Johnson, whose still-standing mansion guarded by two masonry blockhouses at Johnstown had previously been seized by the “rebels.” Fort Stanwix was blockaded since St Leger did not have siege artillery to pound it into submission. Meanwhile, elderly militia General Nicholas Herkimer sounded the alarm and soon rallied some 800 Tryon County militiamen, who marched to the relief of the fort. On August 6, both sides clashed during a thunderstorm at Oriskany, about 8 miles from the fort, which proved to be one of the hardest-fought hand-to-hand battles of the war. At dusk the patriot militiamen eventually retreated having lost a quarter of their men; the winners had suffered 150 casualties and were too weak to pursue. Hearing the musketry fire, Gansevoort led a sortie from the fort, captured St Leger’s nearby camp, and brought back into the fort all the supplies he could. At sunset, the new American standard, the Stars and Stripes, which had just been made in the fort from an old jacket and a petticoat, was hoisted in defiance for the first time over a battlefield. Eventually, General Arnold with 1,200 Americans was sent to raise the siege; as a result, on August 22, St Leger headed back to Canada.

Johnson Hall in the 1760s/1770s, in a painting by Edward L. Henry (1903). The residence of first Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, then his son Sir John Johnson, was flanked by two masonry blockhouses. (Albany Institute of History and Art, Albany, NY; author’s photograph)

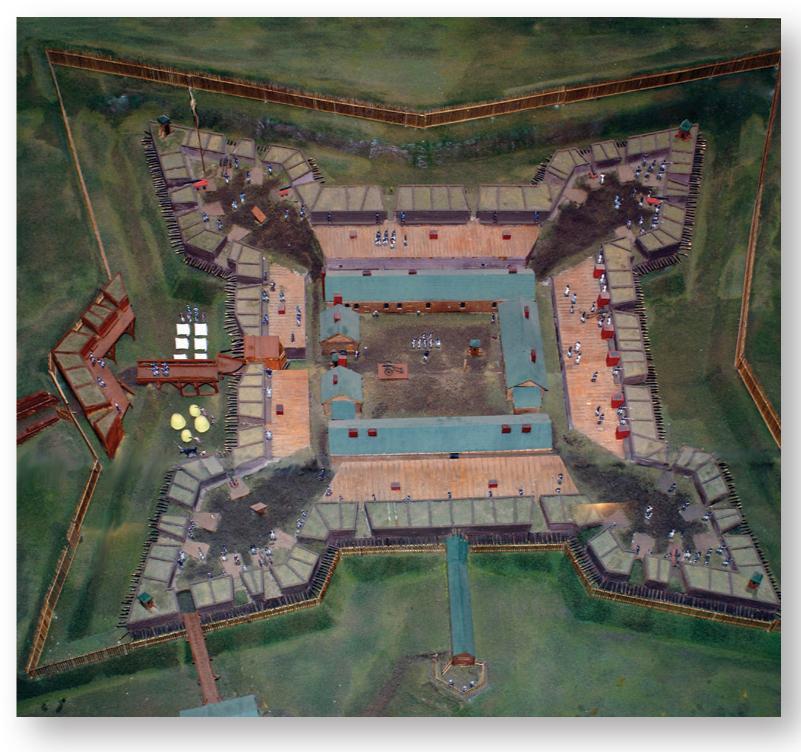

A model of Fort Stanwix at the time of its siege in July and August 1777. All the textbook refinements of a substantial earth and wood fort are shown. Only heavy cannons and large mortars could subdue such a work if well defended, but trains of siege artillery were rarely seen in the wilderness. (Fort Stanwix National Monument, Rome, NY; author’s photograph)

The main army under General Burgoyne left Canada in June. It had 8,000 British and German regulars (nearly all of the latter from the state of Brunswick) accompanied by several hundred Loyalists, Canadian embodied militiamen, and Indians. Nothing stood in its way until it reached the vicinity of Fort Ticonderoga. Burgoyne worried he would be delayed by a formal siege of the old Vauban-style stone fort, but its defenses were crumbling. Nevertheless, the partly sick and poorly supplied 3,000-strong American garrison had built fortifications on Mount Independence overlooking the fort, but not on Sugar Hill, esteemed to be outside artillery range. When Burgoyne’s army reached Ticonderoga on June 30, its engineers correctly concluded that it was within range of heavy artillery and, during the next days, batteries of 24pdr cannons and 8in. howitzers were emplaced on top of Sugar Hill. The American troops withdrew on July 6.

Until then, Burgoyne’s army had travelled by boat, but now had to go through wilderness paths, when there were any, to reach still distant Albany. American opposition was now increasingly present with many skirmishes occurring as the army marched, reaching abandoned Fort Edward on July 30. Thousands of American militiamen and troops in this increasingly populated area were mobilizing to oppose Burgoyne’s army. A first major engagement cast a very dark shadow on its fate. Burgoyne sent a 600-man detachment of German troops led by Colonel Baum to seize stores at the village of Bennington, 30 miles southeast of Fort Edward, but, 6 miles from there, the column was surrounded by thousands of Americans under General John Stark on August 16. The Brunswickers dug trenches around their camp and sent out requests for reinforcements. The Americans, many of whom were excellent shots with rifles and hunting muskets, poured a tremendous fire from covered positions, to which the German soldiers replied; the Americans’ accurate shooting decided the issue and the Germans surrendered after two hours. Sometime later, a relief force of about 550 Brunswick troops led by Colonel Heinrich von Breymann appeared; Stark’s men fell back, but General Seth Warner’s numerous American reinforcements now arrived on the scene. Breymann’s troops fled and isolated riflemen shot at them all the way back to Fort Edward. This showed that European professional soldiers, even protected by field fortifications in a wilderness setting, could be vanquished by accurate small-arms fire. Burgoyne now went to Duer, a secured position between Fort Edward and Saratoga, to regroup his army and gather supplies. Meanwhile, American troops kept arriving in the area, somewhat loosely under the command of elderly General Horatio Gates, whose army eventually numbered as many as 16,000 men. One of his staff officers was engineer Tadeusz Kosciuszko. He had already delayed the advance of Burgoyne’s army by felling trees across the roads and by having all bridges destroyed. Now he identified the area of Bemis Heights, south of Saratoga, on the west bank of the upper Hudson River, as a site on which to build large-scale field fortifications that could stop Burgoyne’s advance on Albany. These fortifications combined extensive earthen and wood lines laid out in a zigzag pattern with outer abatis and numerous outer redoubts. Their eastern side ended on a bluff that commanded the road to Albany and the Hudson River.

Raising the flag of the United States during the siege of Fort Stanwix on August 6, 1777. The American Congress adopted the “Stars and Stripes” national flag in June 1777. It was reportedly made from an old blue jacket and a soldier’s wife’s petticoat, and first raised at Fort Stanwix following Colonel Willett’s victorious sortie against British, Loyalist, and Mohawk Indian besiegers. The scene has been recreated in this 1927 painting. The fort is recreated according to the information then available, but the wilderness shown gives an excellent idea of where North American forts were located. (Fort Stanwix National Monument, Rome, NY; author’s photograph)

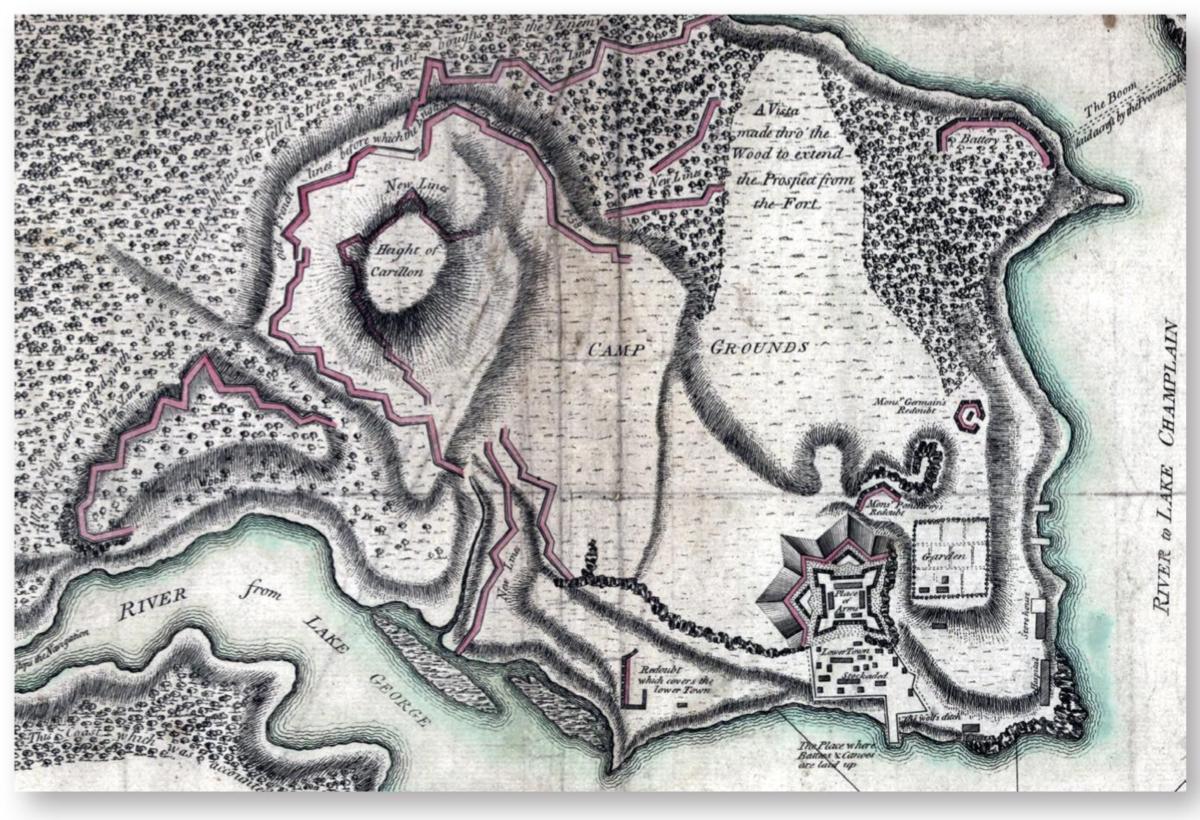

Fort Ticonderoga in 1777, a detail from a contemporary map. The fort was reoccupied by General John Burgoyne’s British Army on July 6, 1777, its American garrison having evacuated the site the previous day. Burgoyne’s army added “New Lines” on the west side next to the older works built by the French during the 1750s. It then moved on, leaving a garrison which was blockaded by American troops. Following Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga on October 17, the garrison of Ticonderoga largely destroyed the fort and its works before retreating to Canada in November. (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Washington)

Meanwhile, General Burgoyne’s army crossed to the west bank of the Hudson River on September 13 and a few days later arrived in the area of the American position some 4 miles to the north. The land between the two armies was a mixture of woodland and cleared fields, one of which was called Freeman’s Farm. On September 19, Burgoyne’s columns advanced, seemingly expecting to carry the American positions fairly easily. However, the Americans put up great resistance in the fields and nearly outflanked the British troops, who finally managed to repulse them. They built field fortifications for protection against possible American raids. In the following weeks, General Burgoyne remained somewhat uncertain as to which course to follow, while General Gates was even more cautious. Then, on October 7, a British reconnaissance force in the woods was met by American troops; the skirmish developed into a full-scale action on the western flank of the British works. The Americans failed to take the Balcarres Redoubt, which had a peculiar elongated shape, but they also attacked the most westerly position held by Colonel Breymann and his Brunswick grenadiers. The Breymann “redoubt” was actually simply a line of logs laid vertically on a height to the north of Freeman’s Farm. General Arnold leading the Americans managed to outflank the defenders and storm the position; during the fighting Colonel Breymann was killed. Its fall was critical in that Americans would now be closing in around Burgoyne’s army. The talented and popular British General Simon Fraser was also mortally wounded by an American rifleman that day. Thereafter, things looked increasingly grim for the British Army, but Burgoyne did not move; his army was surrounded as of October 13. The British Army could hold out in the relative safety of its field fortifications, but it was now completely cut off and, with no hope of relief, Burgoyne surrendered on October 17. It was one of the greatest victories in American history: a whole army made up of professional British and German troops, which had never been able to even approach, let alone attack, the American field fortifications on Bemis Heights, now laid down arms. Not only did Saratoga greatly encourage the Americans, but it convinced France to enter the war on the side of the United States.

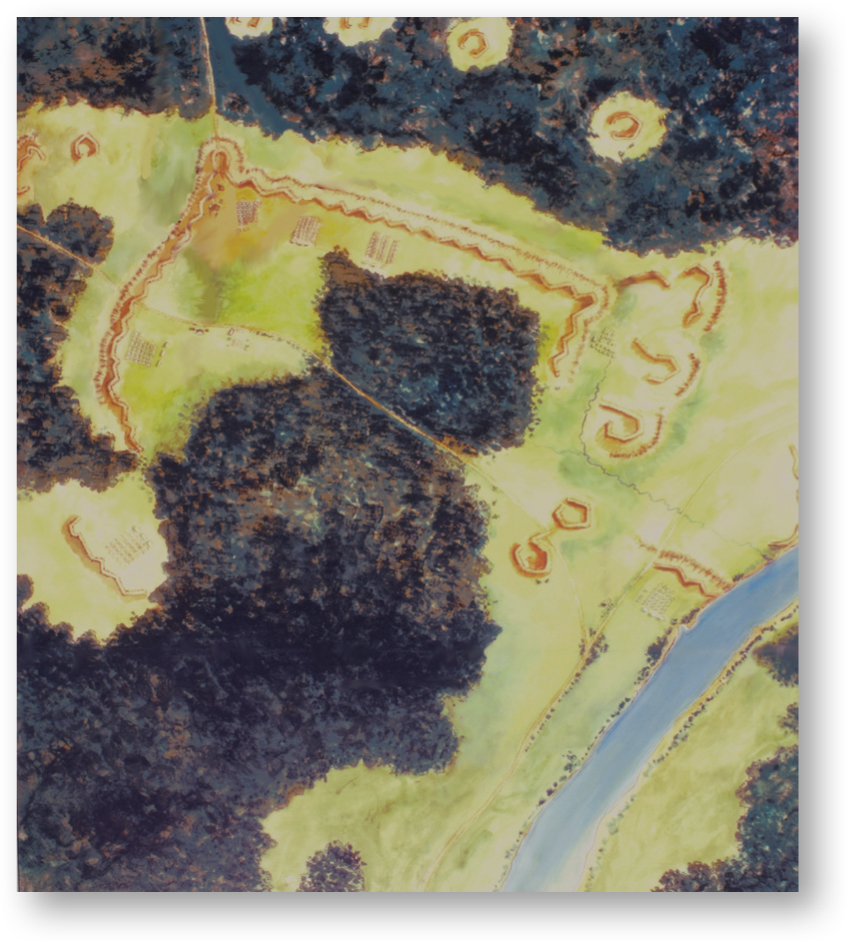

A plan view of the American fortifications on Bemis Heights, late September 1777. General Gates’ headquarters is at lower left; the Bemis Tavern is at the upper right near the Hudson River (shown in light blue). This reconstruction was mainly made from archaeological finds and surviving terrain features. (Saratoga National Historic Site, National Park Service, Saratoga, NY; author’s photograph)

A model of the field of Saratoga in October 1777. This view is seen from the north. The British camp, defense lines, batteries, and redoubts are in the foreground, with those of the Americans further away. (Saratoga National Historic Site, National Park Service, Saratoga, NY; author’s photograph)

Breymann’s Redoubt attacked by American troops at Saratoga, October 7, 1777. Having first failed to take the Balcarres Redoubt, the Americans attacked the defensive position now known as Breymann’s Redoubt, named after the commander of the Brunswick grenadiers that defended what was really no more than a crude barrier of logs laid horizontally. The determined American frontal assaults were supported by a successful flank attack led by General Arnold, who was wounded and lost a leg in the action. This diorama is at Saratoga National Historic Site, National Park Service, Saratoga, NY. (Author’s photograph)

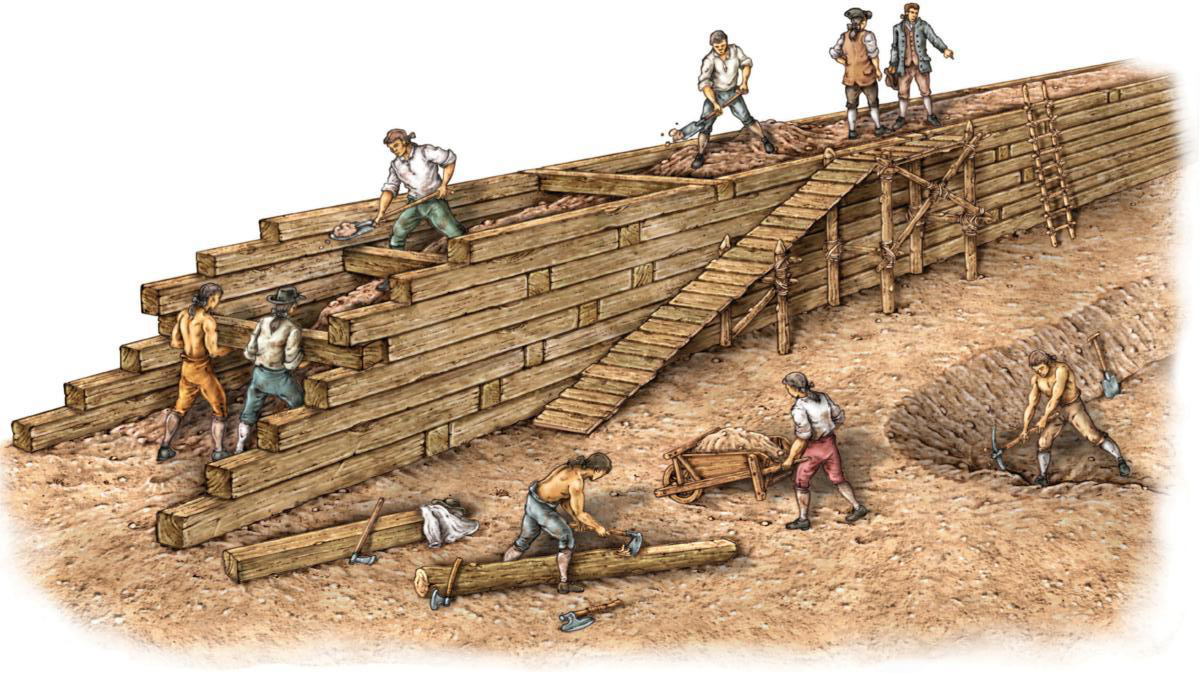

B CONSTRUCTION OF AN EARTH AND TIMBER FORTIFICATION

Fortifications made of timber and earth were very common and almost the only type constructed in North America during the War of Independence. They certainly would not last a long time, but could be erected in a relatively short time if there were enough men to do the work.

The most basic type was the horizontal timber wall, which called for squared logs laid one above the other in two parallel rows with timbers making a “basket work” connecting them for solidity. The empty space between was filled with earth (or other earthy material such as sand and small rocks depending on what was locally available) resulting in a substantial curtain wall that was effective against enemy artillery fire. The construction details could vary greatly depending on circumstances, sites, materials available, and time allowed to build. For instance, the squared logs could be laid on one side, earth stacked up and ending in an abrupt slope whose perpendicular angle would then be revetted on the outside by stacking rectangles of sod (measuring about 3in. × 12in. × 18in.) held in place by small wooden pickets driven through and with the grassy side laid under and not above. Such walls would also have banquettes and artillery platforms with ordnance firing through embrasures made of the same materials.

There could be many other variations. For instance, in warmer climates, bricks could also be used instead of timber. This type of fortification may seem crude compared to fine masonry fortresses, but it provided good protection even under intense cannon fire. With outside ditches and glacis, such forts, be they closed field redoubts or bastioned works, were effective strongholds that required considerable effort to overcome and could render horrendous casualties to assault troops in the process.

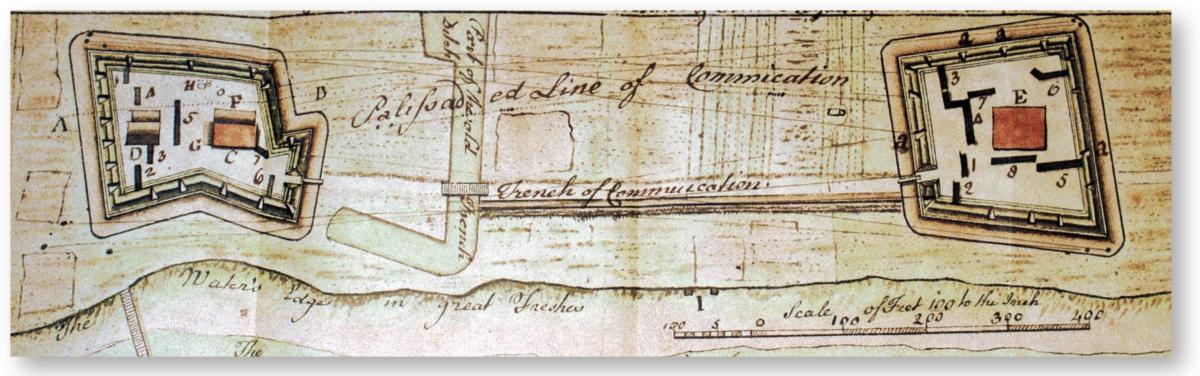

Philadelphia

Meanwhile, General Washington’s and General Howe’s armies fought several battles, chiefly in Pennsylvania, but without being able to destroy each other’s force. These were largely field engagements involving minimal use of fortifications. One of the British objectives was the largely unfortified city of Philadelphia, then the capital of the United States. On September 26, 1777, General Charles Cornwallis, second-in-command to Howe, entered the city with part of the British Army to the acclamation, it should be added, of several thousand Loyalist inhabitants. However, the Continental Army was not destroyed and was lurking outside the city, so a line of defensive earthworks with ten redoubts stretching from the Schuylkill River to the Delaware River was built by the British north of the city. The Americans also held forts Mifflin and Mercer that commanded naval access to Philadelphia by the Delaware River south of the city. Fort Mifflin, situated on Mud Island, had been built in 1771 under the direction of British engineer John Montresor. It was an especially strong work with an innovative design having its southeast curtain wall echeloned in succeeding bastions to provide increased firepower on river traffic that could also crossfire with the smaller pentagonal Fort Mercer on the opposite, eastern shore. These American-held forts, with their supporting smaller works, simply had to be taken by the British to secure their naval communications to Philadelphia. On November 22, a force of 1,200 German troops from Hesse-Cassel under Colonel Carl von Donop moved toward Fort Mercer with its garrison of 400 Rhode Island troops under Colonel Christopher Greene. It had just been reinforced with earthworks 10ft high faced with planks with a deep ditch and abatis designed by Thomas-Antoine, chevalier de Mauduit du Plessis, a young French officer who had joined the American cause. Greene felt there was no point sacrificing his garrison at the outworks, and so had them dismantled, deciding to make a stand at Fort Mercer instead. The Hessians’ assault was heroic due to the enormous difficulties they encountered trying to cross du Plessis’ fortifications, but was doomed when American armed galleys in the river poured enfilading artillery fire on their columns. Von Donop was mortally wounded and about 400 of his men were killed, wounded, or missing, while the Americans suffered about 40 casualties.

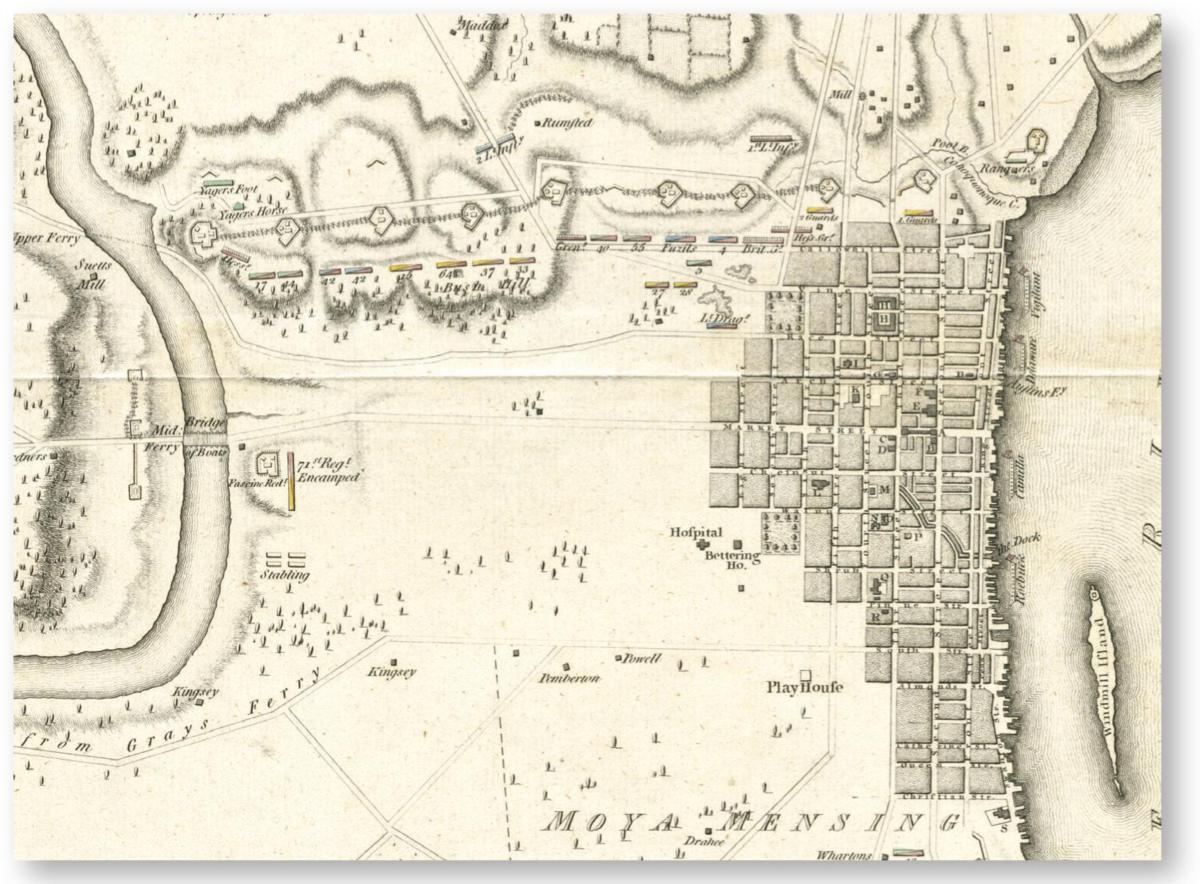

Philadelphia in 1778, taken from a map published in London on January 1, 1779. Philadelphia had no fortifications, so the British Army built a line of field fortifications featuring ten redoubts north of the city between the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers, where most of the troops were encamped. (Courtesy Richard H. Brown Revolutionary War Map Collection, Boston Public Library)

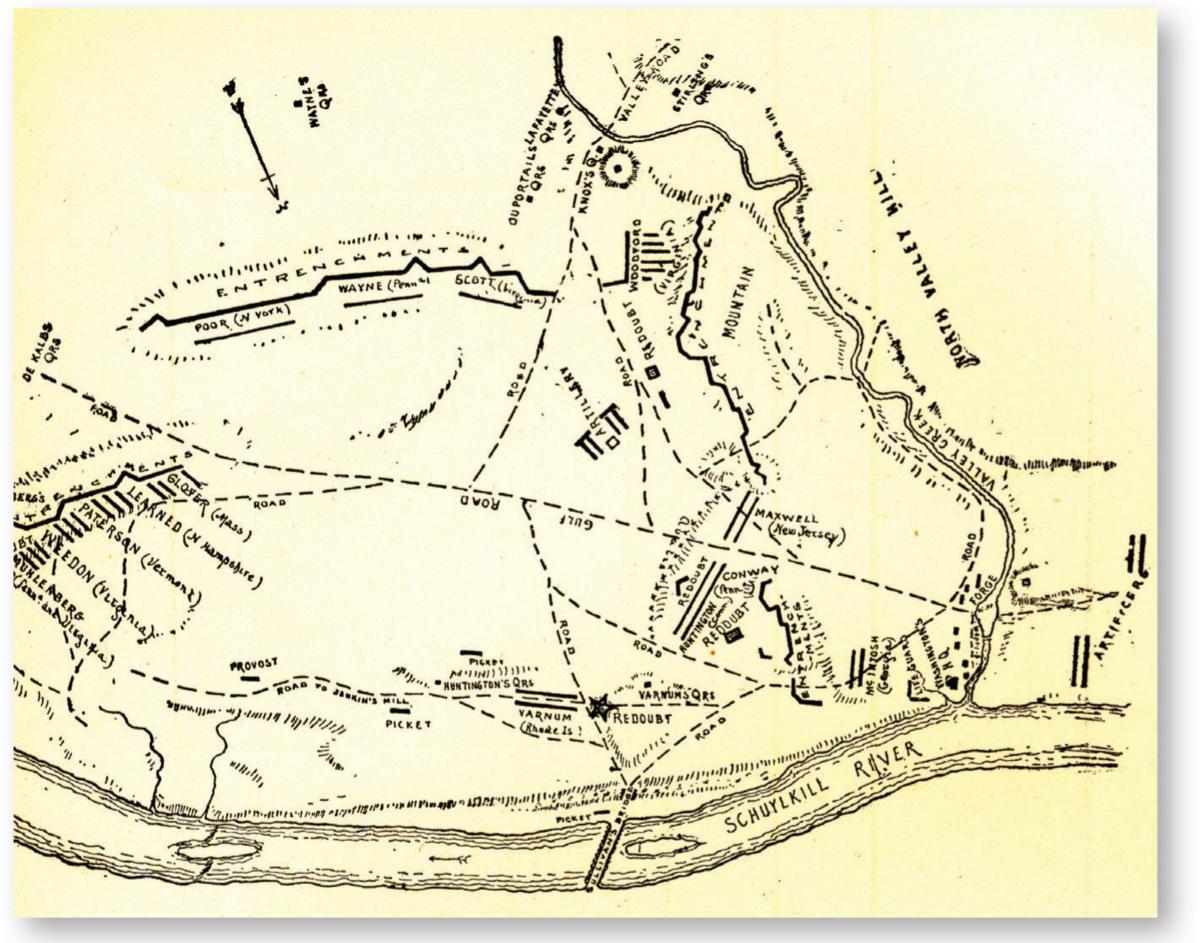

The camp of the Continental Army at Valley Forge, 1777–78. The southern side of the camp was protected by outer entrenchment lines manned by troops from the various states as indicated. More entrenchments and redoubts were in the vicinity of Washington’s headquarters (at lower right). (Private collection; author’s photograph)

The British command then decided to take Fort Mifflin, the key to all the American positions on the river. They moved into nearby Carpenter’s and Providence islands and set up batteries to the west of the fort. Joined by six Royal Navy warships, an intense bombardment rained projectiles on Fort Mifflin from November 10 to 15. By the evening of the 15th, its 400-strong garrison had suffered some 250 casualties and the fort’s works “were entirely beat down; every piece of cannon entirely dismounted,” as General Washington later wrote; he added that its “defense will always reflect the highest honor upon the officers and men of the garrison,” which were led by Major Samuel Thayer. The American flag remained flying over the fort while the garrison evacuated that night. General Howe then sent Cornwallis, at the head of some 5,500 troops, to secure the eastern shore of the Delaware River, including Fort Mercer, which was also evacuated. The British now had naval access to the former American capital, whose modest fortifications had nevertheless provided numerous obstacles for the attackers. Once again, the Americans had shown they could be a formidable opponent in defensive positions.

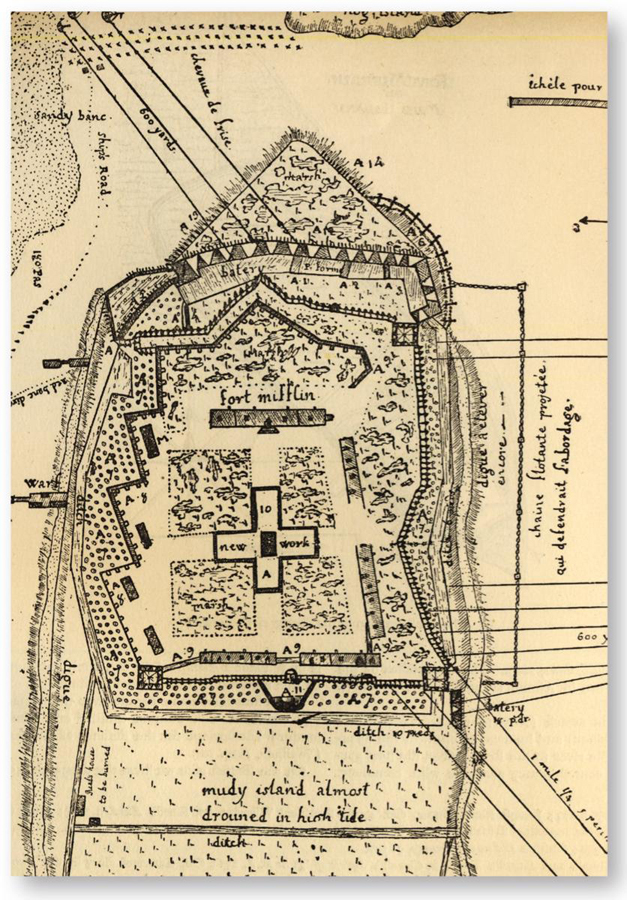

Fort Mifflin, November 9, 1777, in a drawing made by Major Louis Fleury, a French officer with the American garrison, a day before the start of the British bombardment. The south is at top. The plan shows the fort’s substantial gun positions on its walls and at the outer battery facing the Delaware River, since it was originally designed to protect Philadelphia from a hostile naval force. Its weaker side, as shown by the many lines (at right) coming from the west, was exposed to British shore batteries. Fleury was later present at Yorktown as a major in the Saintonge French infantry regiment. (Private collection; author’s photograph)

Washington’s Continental Army was, at that point, the only viable field force that could oppose the British and German troops, and it retired to the hills at Valley Forge, northwest of Philadelphia, for the winter of 1777/78. Like a Roman general, Washington always fortified any place that his army occupied and, being a former surveyor in his younger years, helped lay out various field works that made Valley Forge next to impregnable. The victory at Saratoga had been great news, but food, medication, uniforms, and warm clothes were in short supply for the soldiers huddled in crude wooden huts in the snow that winter at Valley Forge. By early February 1778, nearly 4,000 men were sick while others, famished, had deserted or were so discouraged they were near to mutiny. However, through it all the will to fight rarely wavered; the remarkable work of another professional officer, Baron Friedrich von Steuben, former staff officer to King Frederick the Great of Prussia, relentlessly drilling and training the Continental soldiers during the winter brought the Americans to a hitherto unseen level of discipline, efficiency, and capacity to maneuver on the field on par with contemporary European armies whilst preserving the effective American light-infantry fighting methods.

Furthermore, France’s recognition of the United States in February 1778 brought much encouragement to the colonies, for it promised substantial material, monetary, and manpower assistance would eventually be forthcoming. However, recalling the events of the Seven Years War, many Americans must have fervently hoped that the French Navy and Army would perform better when hostilities began between France and Britain, which they did in July 1778. By then, Valley Forge, which had never been approached by British troops, had been abandoned. Contrary to expectations, the entry of France into the conflict necessitated the evacuation of Philadelphia, the British Army leaving the city on June 18, 1778, to regroup at New York: the British command needed to reinforce and concentrate its forces in case a squadron from the new and powerful French fleet intervened in America. Indeed, the French went on the offensive in the West Indies, gaining several victories against the British, who were forced to send reinforcements from New York to the islands; to compound matters, sudden fear of a French invasion gripped Great Britain itself. Seeing General Clinton abandon Philadelphia, General Washington attacked the British rearguard at Monmouth, New Jersey. Clinton ordered a counterattack and American General Charles Lee, lacking confidence that his troops could stand against British regulars, ordered a retreat of some 15 miles. Lee’s withdrawal ended when a furious Washington ordered Lee off the battlefield, and formed a line that, assisted by a battery on a hill, stopped and then forced the British to withdraw to New York City the same night. The fighting at Monmouth showed that the Continental Army trained by von Steuben could hold its own in an open field as well as behind earthworks.

A plan of Fort St John (or Saint-Jean), 1775. In September, both redoubts were completed and armed with about 30 pieces of artillery, amongst which were two 8in. howitzers, eight Royal or Coehorn mortars, two 24pdr brass cannons and six 9pdr iron cannons; other weapons were of small caliber. (Courtesy Library and Archives Canada)