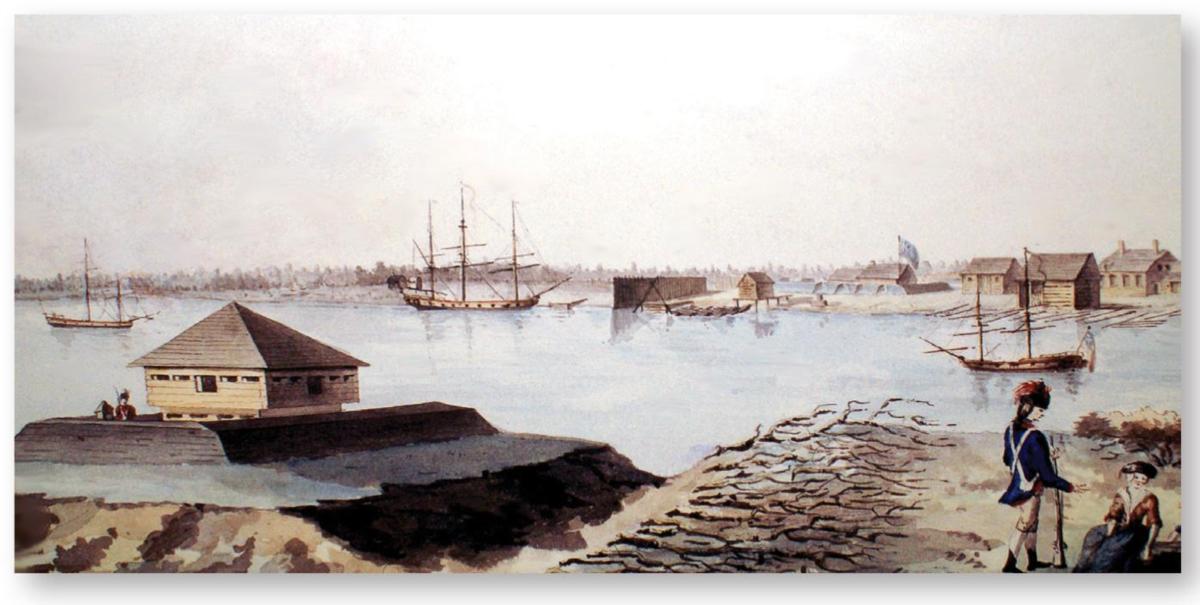

The siege of Fort St John, September 1775. Three American batteries bombard the two redoubts that form the fort. (Courtesy Library and Archives Canada)

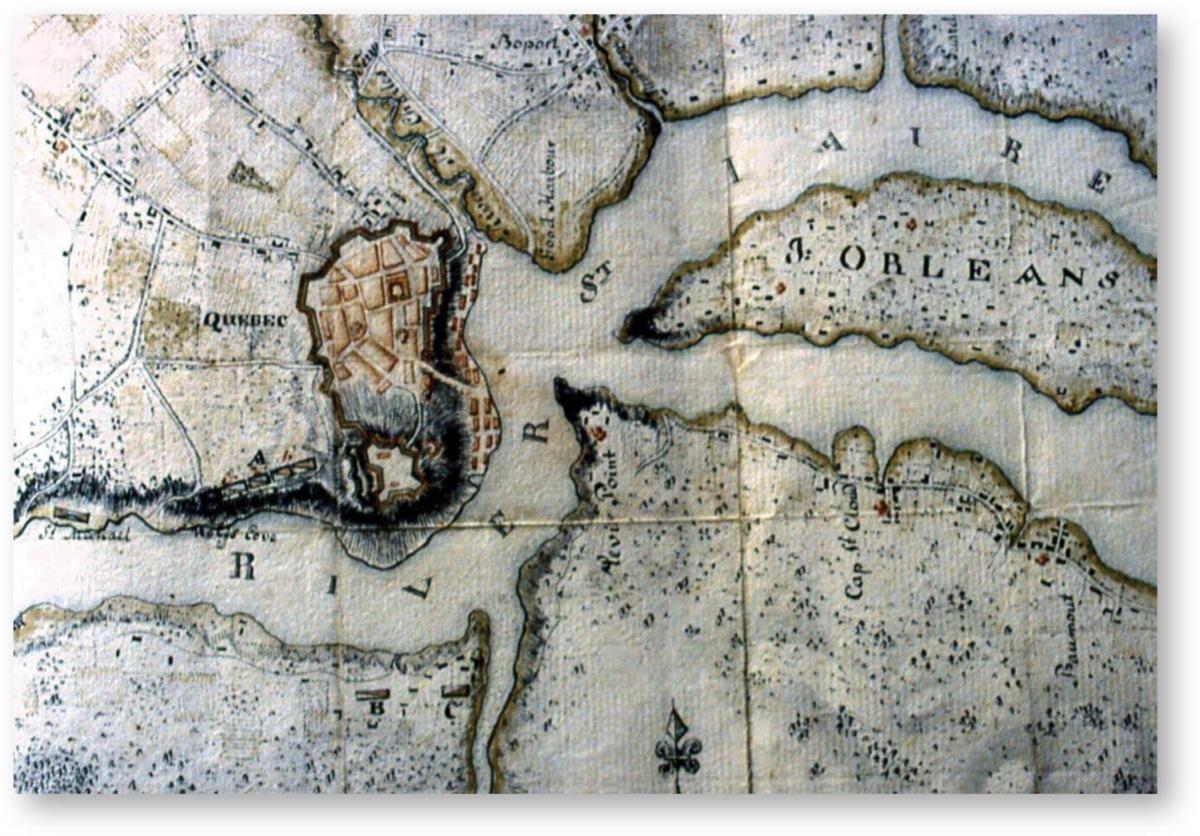

In September 1775, while the siege of Boston was in progress, General Washington detached 1,000 infantrymen with three companies of riflemen under General Benedict Arnold from his army to advance to Quebec through the forests of Maine. There, they would join General Richard Montgomery’s army of about 2,000 men that was invading Canada by Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River; the plan was for Montgomery’s troops to take Montreal and then march on Quebec. As it turned out, the daring plan to conquer Canada ran into difficulties caused by fortifications. Montgomery’s army had no opposition until September 6 when it came to Saint-Jean, or St John, on the west bank of the Richelieu River. Since 1665, this place had been the site of several successive French forts that were in ruins by 1775.

Anticipating a possible American foray, Sir Guy Carleton, governor of Canada, had tasked Major Charles Preston of the 26th Foot to have fortifications built at Saint-Jean. Preston, who knew this had to be done quickly, chose to erect two strong redoubts connected by a 700ft-long “trench of communication.” These works were built by 300 men from July to September and armed with some 30 guns. While the Americans landed south of the fort, a party of First Nations warriors (indigenous Canadians not part of the Inuit and Métis) allied to the British ambushed them, killing several before withdrawing. The Americans persisted during the following days and invested the fort. The siege started on September 18; some 567 men, mostly from the 7th and the 26th regiments with some Canadian militiamen, garrisoned the redoubts. There were also about 700 women and children seeking refuge, so that some 1,300 people were huddled in those two small redoubts. These were strong enough to discourage the Continental Army from attempting an assault and the Americans strived instead to secure the immediate area, notably by occupying nearby Fort Chambly on October 18, where they found ample ammunition and supplies. Initially, the artillery in the redoubts was far superior to the few guns the Americans had and the British and Canadians could fire ten shots to every American round.

The siege of Fort St John, September 1775. Three American batteries bombard the two redoubts that form the fort. (Courtesy Library and Archives Canada)

Although Major Preston and his troops were relatively secure in these earth and wood redoubts, they were totally isolated with little hope of relief since there were few regular soldiers left in Montreal or Quebec. The Americans realized that the only way to take Saint-Jean without risking high casualties in an assault was to pound it with relentless artillery bombardments. This would take precious time, but it was the only sensible course of action. Consequently, some of the heavy guns at Fort Ticonderoga were brought up to Saint-Jean and three batteries were built, for a total of eight mortars and ten cannons. The effect to those in the redoubts was soon apparent. Canadian militiaman Foucher mentioned that, on November 1, the Americans fired about a thousand rounds on the fort, many of them mortar bombs. The weather was rainy and the damaged earthen redoubts were very muddy. By then, there was hardly any ammunition left and rations to feed the 1,300 besieged would only last a few days more. Major Preston now felt he had resisted all he could. On November 3, Fort Saint-Jean surrendered after a valiant defense. Its resistance was remarkable considering it consisted of only two redoubts, and it delayed Montgomery’s plans to conquer Canada in the fall. Now, the weather was becoming colder and the severe rigors of a Canadian winter were rapidly approaching. Ten days later, the Continental Army entered Montreal; the few defending troops left had retreated with Governor Carleton to the fortress of Quebec.

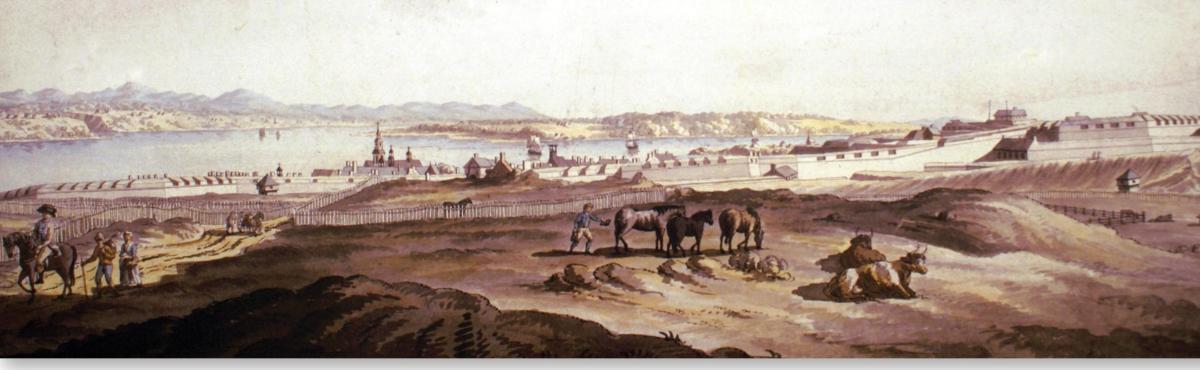

A model of Fort St John in 1775, at the Musée du Fort Saint-Jean, Saint-Jean (Quebec). The fort consisted of two redoubts linked by a trench or covered way. (Author’s collection)

Detail from A South West View of St John’s, August 1779 – a watercolor by James Hunter. The two redoubts are on the west side of the Richelieu River, with the northern redoubt clearly shown and the southern one only faintly. After the British reoccupied the area in 1776, the eastern bank was also secured, as witnessed by the blockhouse in a redoubt in the left foreground. (Courtesy Library and Archives Canada, C1507)

Meanwhile, General Arnold and about 700 men arrived in front of the fortress city on November 15 after a grueling trek through the wilderness and, on December 3, Montgomery and his troops joined them. The American army then stood at about 2,000 men and it set up its camp on the Plains of Abraham, on the west side of the fortress. In the city were 1,120 defenders of which some 800 were militiamen, the rest being sailors, artificers, recruits, and a company of regulars of the 7th Royal Fusiliers.

For generals Montgomery and Arnold, the crucial problem facing them was how to attack Quebec city. There was no crumbling and inadequate curtain wall surrounding the city, as there had been at Montreal – Quebec was one of the mightiest fortresses in the Americas thanks chiefly to its location on Cape Diamond. Its constructed fortifications were not especially formidable or extensive and it did not even have a powerful masonry citadel featuring all the latest refinements. The modest walls surrounding the 17th-century Château Saint-Louis, residence of the governor general of Canada, would not make much of a redoubt despite being called a “citadel” (the scenic Château Frontenac Hotel now occupies the site). Moreover, the initial attempts to build a larger timber and earth citadel on Cape Diamond at the southwestern end of the walls had barely begun in 1775. On the other hand, the masonry curtain walls built by the French were maintained by the British and improved to some extent, notably by finishing the ditches outside the western side. There were various small batteries spread all around the city too. However, what really made Quebec such a mighty fortress was its location on the cape. It was a natural fortress that, like the Rock of Gibraltar, merely needed a modest amount of fortifications to make it almost impregnable.

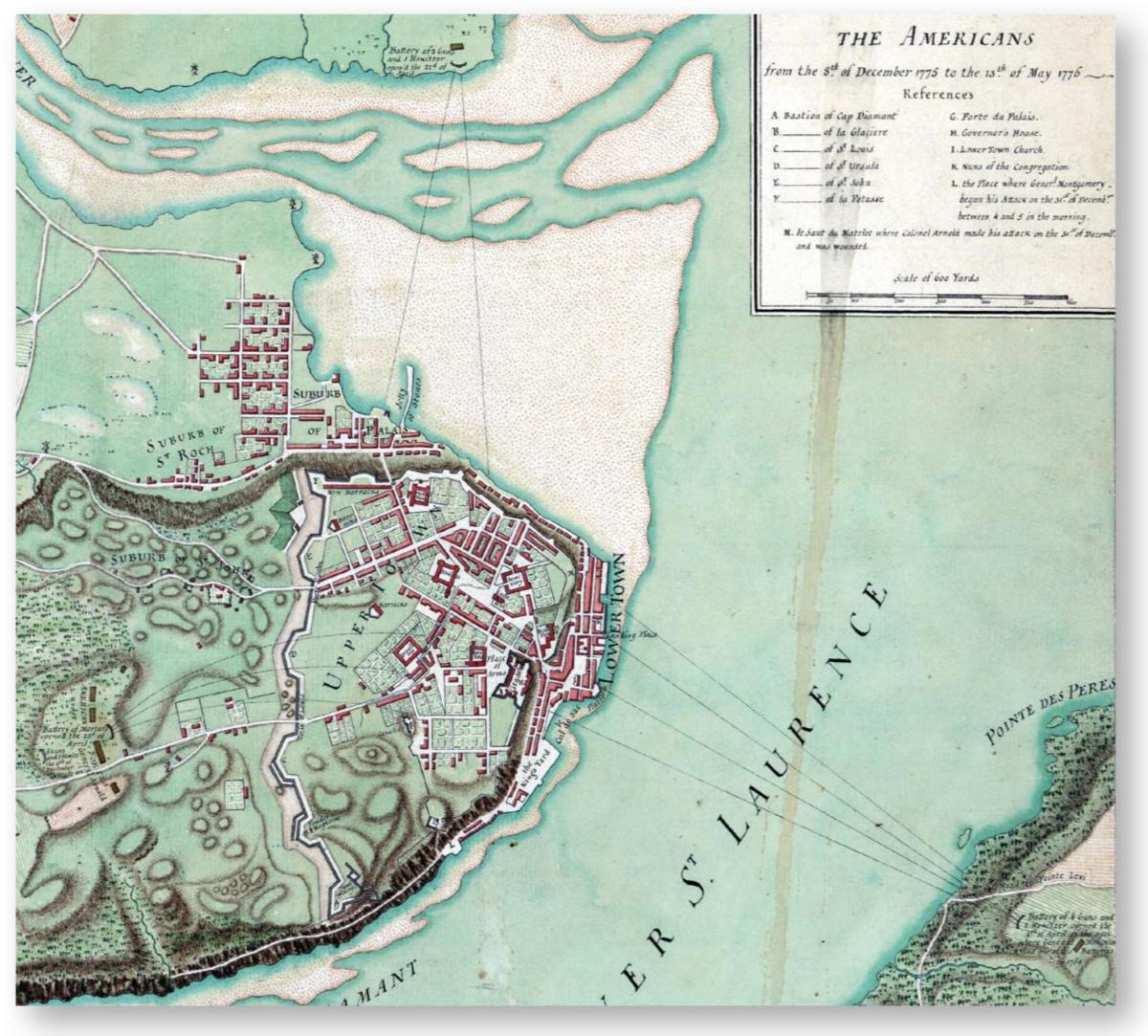

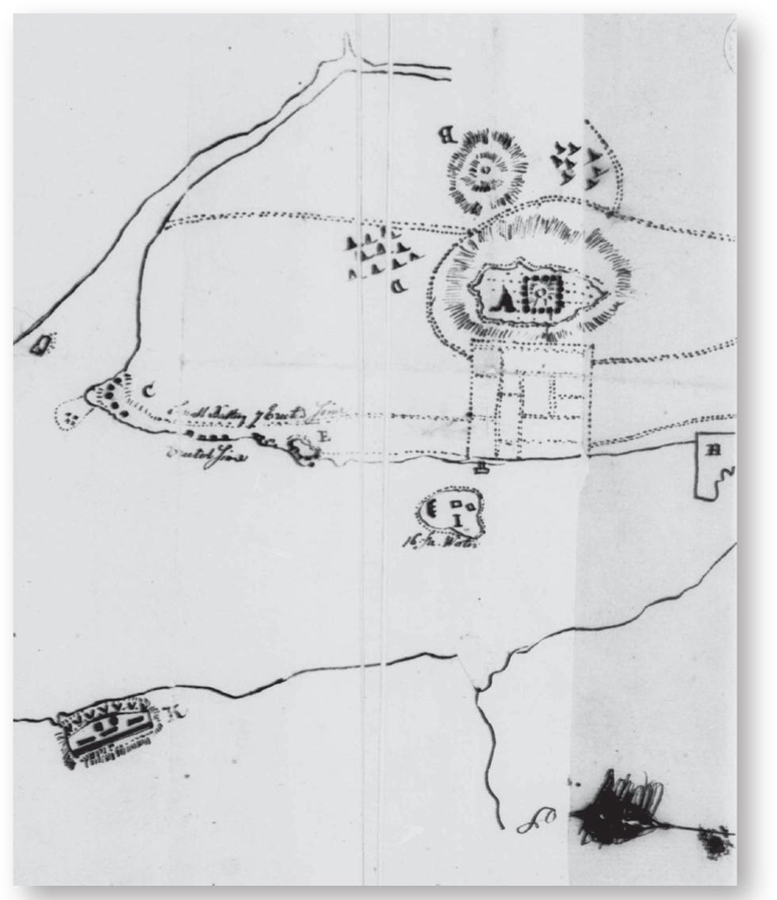

Plan of the siege and blockade of Quebec, from December 8, 1775 to May 13, 1776. From April 1776, the Americans had three modest batteries (visible at left, top and right) to bombard the city. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington)

Quebec has a narrow Lower Town built on a narrow strip of land going from the shore of the St Lawrence River to the foot of the cliff that ascends to the citadel. Many merchants had their residences and warehouses in this lower area, whose hub was the Place Royale and its Notre-Dame-des-Victoires or Lower Town church. There were three shore batteries facing south, of which the bastion-shaped redoubt or Batterie Royale was the most important; in 1775, however, the Americans had arrived by land and so it served little defensive purpose. To get from the Lower Town to the Upper Town built on top of the high and steep cliff, one needed to walk up the Côte du Palais or the Sous le Fort streets, both of which had strongly fortified gates. An important detail was that the private housing in Quebec City was generally made of stone and masonry and therefore sturdier than the brick and wood residences found in most other North American cities. As noted above, the west side had a masonry and bastioned rampart with a ditch in front and clear fields with no buildings; the St Louis and Saint-Jean (or St John) fortified gates controlled access. Montgomery’s and Arnold’s men were encamped further west of this wall and it was obvious to the Americans that an assault, even on that somewhat weaker side, was near suicidal.

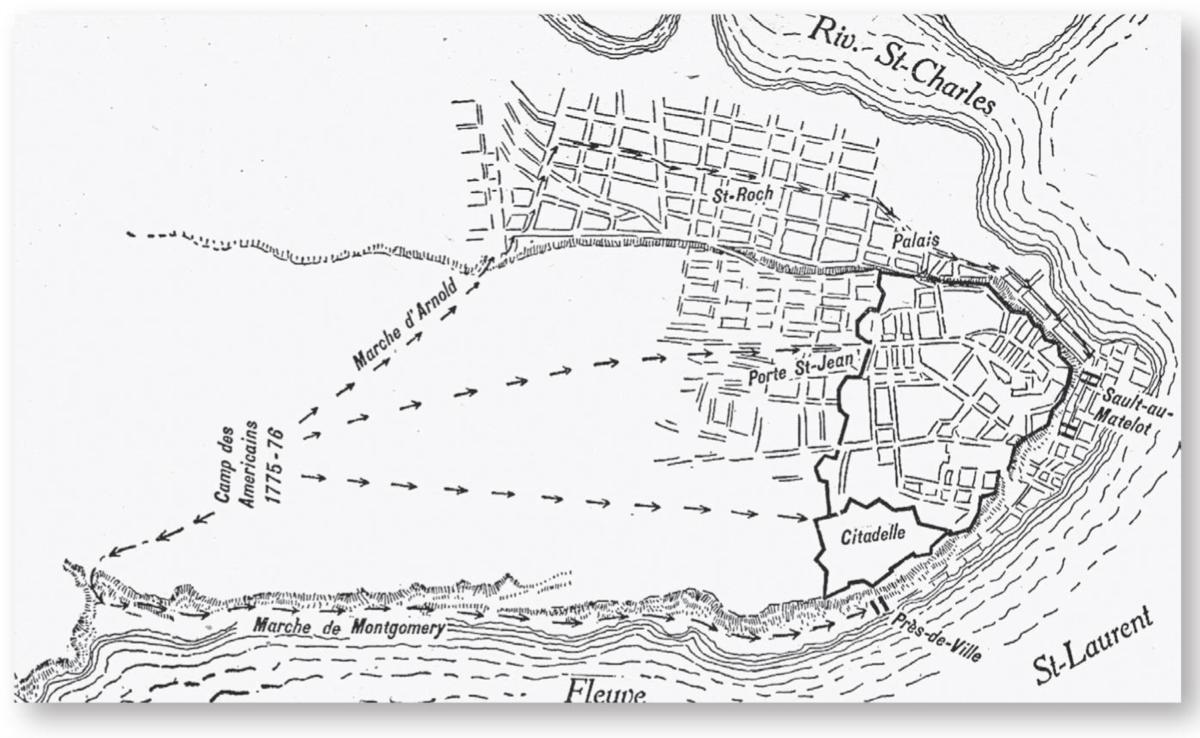

The American commanders carefully considered what to do against such a strong position and came up with a novel and daring plan. An assault would be made at night, in the darkness. Two feints would be made against the western walls of the Upper Town: one to the south of the St Louis Gate and the other against the St John Gate. Simultaneously, two strong columns comprising most of the American troops would make their way along Cape Diamond near the shores of the St Lawrence, secure the Lower Town, and storm the gate leading into the Upper Town at the Bishop’s Palace. The first and strongest column under General Arnold would come from the north by Sault-au-Matelot street. The second column would come from the west, pass under the heights of Cape Diamond, secure the Près de Ville and the King’s Shipyard position, then ascend with Arnold’s men into the Upper Town. If successful, this plan could indeed deliver hundreds of American troops into the city and subdue the mighty fortress.

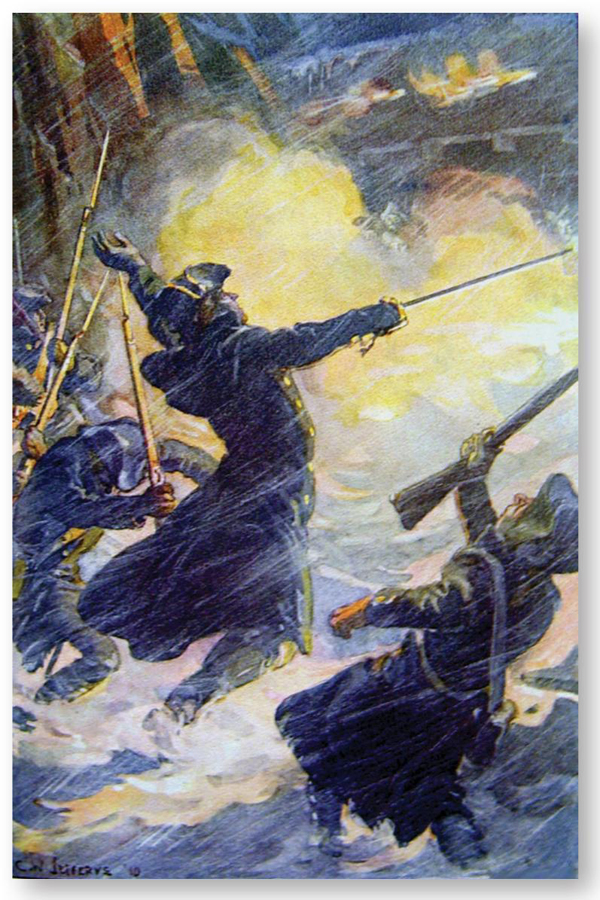

The death of General Richard Montgomery at the Près de Ville access to Quebec City’s Lower Town on the night of December 31, 1775, in a print after C. W. Jeffrey. Canadian militiamen poured musket and cannon fire onto the Americans huddled in the stone buildings. (Author’s collection)

Carleton, however, had planned for the possibility of such an attack via the Lower Town. Various obstacles and two barriers had been erected on Sault-au-Matelot street with another, containing some artillery, at Près de Ville. Several American deserters spoke of a Lower Town attack, so the garrison was on high alert. Indeed, in the early hours of December 31, the Americans formed their column and moved in for the attack. It was a dark night and it snowed, which reduced visibility and muffled sound. At about 4.00am, some of Quebec’s sentries thought they saw lights in the sky through the storm. Captain Malcolm Fraser saw them too and, although no one knew what they meant, he took no chances and sounded the alarm. Drums started beating and the city’s church bells rang. Hearing this, the Americans fired two rockets over Cape Diamond while opening cannon and musket fire on the city’s west side; the two feints there were meant to draw attention. Meanwhile, Montgomery and his party were advancing, with some difficulty due to banks of snow below Cape Diamond, on the then fairly narrow path between the river and the cliff, reaching after some delay the strong picket fence erected at Près de Ville. No defenders were seen and pioneers sawed an opening through it. The Americans went on until they reached a second picket fence, through which another opening was made. Montgomery and his officers emerged through this in the dark not far from a barely visible house nearby. “Push on brave boys, Quebec is ours!” shouted Montgomery, charging in with his officers and a Canadian guide. Seconds later, tremendous cannon and musket fire swept nearly every American near the house; only Aaron Burr – a future American vice president – was left standing, unhurt but dazed. Around him, Montgomery, many officers and the guide lay dead or dying in the bloodstained snow. The barely visible stone and masonry house had been turned into a redoubt defended by Captain Chabot with about 30 French-Canadian militiamen and a few sailors. The Americans retreated in confusion; the surprise attack had been thwarted by a surprise ambush, and the commanding general had been lost.

A plan of the American assaults on Quebec City during the night of December 31, 1775, from Histoire du Canada (1915). Four columns exit the American camp (Camp des Américains) west of the city; two are feints on St John’s Gate (Porte Saint-Jean) and near the citadel (Citadelle) further south, while the other two are the true assault columns led by Arnold to the north and Montgomery to the south. However, both of the latter were to encounter obstacles at Sault-au-Matelot and Près de Ville. (Author’s collection)

The American attack in Quebec City’s Lower Town runs into the second barricade held by Canadian militiamen and British troops on the snowstorm-filled night of December 31, 1775, as depicted in a diorama in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa. Note the sturdy timber barricade blocking Sault-au-Matelot street between two stone buildings. The defenders repulsed the Americans, who launched further attacks from the rear of their column. (Author’s collection)

This disaster was unknown to General Arnold’s main column of about 700 men moving down in the dark from the north towards the center, hampered by snow drifts. When the vanguard of the Americans reached Côte du Palais street, they were spotted by the city’s sentries up on the wall, who gave the alarm and fired on them. Arnold, believing that Montgomery was moving in his direction, pressed his men to move on until they reached some cover provided by warehouses. However, a barricade blocked Sault-au-Matelot street, defended by a militia detachment with two small guns that put up a vigorous defense. General Arnold was wounded in the knee before his men withdrew. With Arnold now taken away to the American hospital, Colonel Daniel Morgan led the assault force down the street until he came to a second barricade erected between sturdy stone buildings. While this barricade was stubbornly held by a detachment of the 7th Royal Fusiliers with about 200 Canadian militiamen, Governor Carleton seized the initiative and ordered a counter-attack by a column that charged down from the Côte du Palais, erupting on the flank and rear of Morgan’s American troops; they were doomed, and after some sharp fighting in which about 150 were killed or wounded, some 389 surrendered. The British and Canadians suffered at most nine killed and wounded, which gives an idea of how secure they were in the great fortress.

A map of Quebec City and its immediate area, 1780, drawn by Bernard Weiderhold, a German officer in British service. The outline of the wood and earth citadel is clearly visible. (Portuguese Army Library, Lisbon; author’s photograph)

View of the Quebec City walls facing west, a watercolor by James Peachy. The top of St John’s Gate (Porte Saint-Jean) and its bastion is seen at center and left. As with the great majority of Quebec’s fortifications, the curtain walls, bastions, and gates had been built by French engineers in the 1740s and maintained by the British after 1759. (Courtesy Library and Archives Canada, C1515)

Despite the failed assault, the siege by the remaining American force of about 1,000 men, huddled in their camp during the rigors of a Canadian winter, continued. It was a much-weakened force that could, at best, only block access into Quebec. It had few artillery pieces and building batteries was out of the question in winter. For Carleton and his officers, there was no inclination to risk a sortie or attempt skirmishes by raiding parties; the men of the garrison were overwhelmingly city dwellers rather than woodsmen, so it was wiser to hold the fortress until relief came from Britain in the late spring, once the St Lawrence was clear of ice. In the meantime, work continued in the city to strengthen existing defenses. To avoid further surprise attacks from the Americans, the west curtain walls were kept well lit with fires burning from sunset to sunrise; additionally, lanterns tied to poles were extended over the ditches. There was plenty of serviceable ordnance in stores and much of the winter was spent arming the walls. By May 1, 1776, some 148 cannons were mounted and in position. The existing defenses denying access to the Lower Town were also strengthened: at Près de Ville, the nearby iced-in ships moored for the winter were armed with guns thus becoming outer batteries. A wide trench was also cut in the ice from the shore to the open water at the center of the river so that Americans could not outflank the shore defenses by going over the ice. In the Sault-au-Matelot sector, the barricades were strengthened, guns were mounted, and, to secure clear fields of fire, houses lining the street were destroyed.

In the meantime, General Arnold was recovering from his wounds and hardly in a mood to attempt another assault; an unlucky horse fall injured him further and he was relieved by General Wooster on March 31. The Americans kept up the semblance of a siege and, as the milder weather of the early spring appeared in late March and early April, they built three small batteries to harass the city. The battery of four guns and a howitzer at Pointe-Lévis opened up on April 4, with the one on the north shore of the St Charles River comprising only two guns and a howitzer starting on April 22, and a mortar battery on the Plains of Abraham firing its first bombs the following day. However, throughout the siege the artillery mounted on the walls of the city was far superior. According to Sanguinet’s account, from December 1775 to May 6, 1776, the Americans fired 784 cannonballs and 180 mainly small mortar bombs into the city wounding only two sailors, with the sole fatality being an unfortunate eight-year-old boy killed by a cannonball. During the same period of time, the city’s artillery fired 10,466 cannonballs and 996 mortar bombs towards the Americans. On May 3, the Americans attempted and failed to float a fire ship into the Lower Town harbor. Three days later, the frigate HMS Surprise was sighted to the east followed by two more ships; they were the vanguard of a fleet bearing troops and supplies from Britain. The British ships moored in Lower Town, and soldiers poured out. Governor Carleton joined them with most of the garrison, which then made a sortie towards the American camp on the Plains. Seeing all this, the Americans panicked and fled, leaving their artillery and even their suppers, which were consumed by British and Canadian troops.

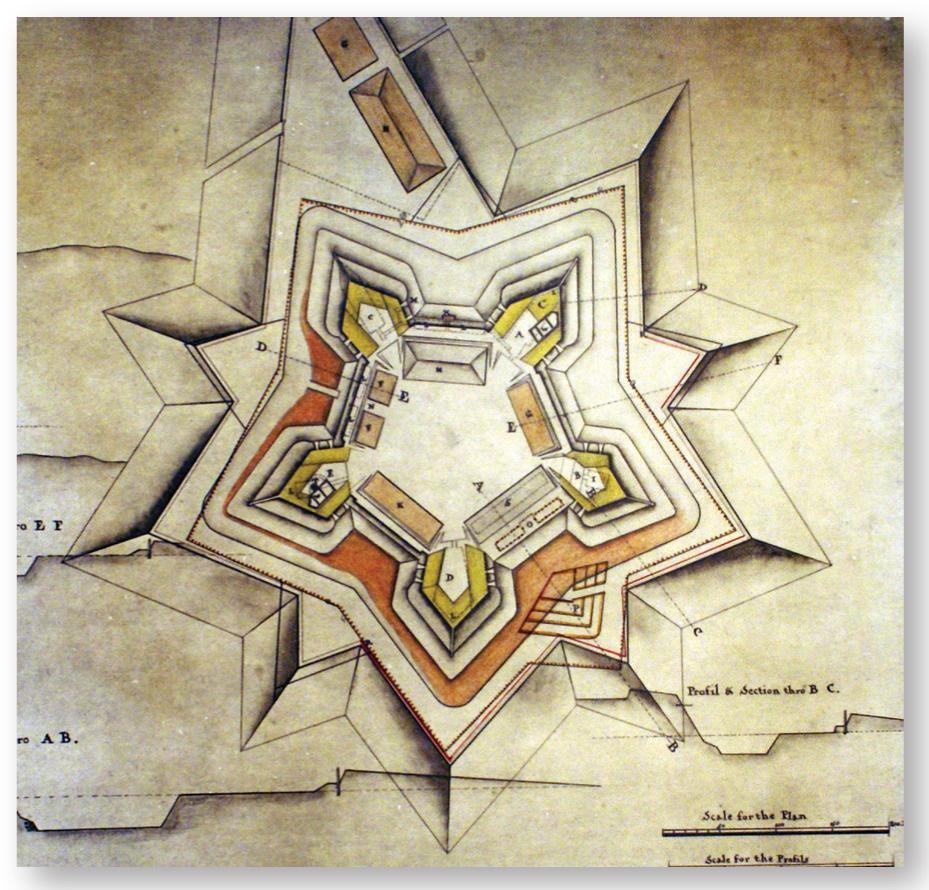

Plan of Fort Cumberland, c.1757. This was the former French Fort Beauséjour until captured by the British in 1755 and renamed Cumberland. Its British garrison was withdrawn in 1768 and it was then reoccupied by Loyalist troops in 1776. It essentially remained the star fort as built by the French, although the British had made a few changes prior to 1768 such as the elimination of the ravelin (P at lower right) and built new barracks outside (H at top). (Fort Beauséjour National Historic Site, Parks Canada; author’s photograph)

Outside of Quebec City, the overwhelming majority of the population was of French origin and, while small numbers sided with either the Americans or the British, the population remained generally neutral in what appeared to be a fight between their former British and American enemies. Furthermore, American rule in Montreal had not been especially popular; now the British relief force was marching towards Montreal from the east. Meanwhile, British posts on the Great Lakes such as forts Frontenac, Niagara, Detroit, and Mackinac, which had small garrisons, had not been invaded. In May 1776, a mixed party under Captain George Foster of 41 British regulars from the western forts, 210 First Nations allies, and 41 Canadian militiamen was approaching Montreal from the west. On May 18, when this force came to Les Cèdres (or Cedars) on the north shore of the St Lawrence, about 45 miles west of Montreal, it found a small stockade fort recently built there and garrisoned by about 400 American soldiers with two 4lb cannons under the command of Colonel Isaac Butterfield, sent there by General Arnold to guard the western flank of the Continental Army. After some light skirmishing, the Americans – who seem to have especially feared the First Nations warriors – stayed in the fort, which also had a line of trenches outside, while Foster had a breastwork made of fence posts built around the fort. The next day, although they lacked any form of artillery, Foster’s men maintained brisk musket fire on the American position, and Butterfield capitulated with 390 men and the cannons. Other skirmishes followed; the Americans retreated south and General Carleton’s troops reoccupied Montreal, Chambly, and Saint-Jean.

C TIMBER BLOCKHOUSE

Blockhouses, whose north European origins are obscure, were seen as early as 1622 in Plymouth Pilgrim Colony and spread to other English colonies. They were ideal self-contained, small strongholds that could be rapidly put up with logs, or squared timbers if there was more time to build. Both the Americans and the British used them extensively during the American War of Independence. They were usually built on a square or rectangular plan, two stories high, the second story overhanging with a sloped roof, and containing loopholes for muskets, windows that became portholes for ordnance, and machicolation in the overhang to permit defenders to direct a downward fire. Since they were living quarters, they had a chimney with fireplaces, sleeping bunks, and other implements for the soldiers within. A ladder gave access to the upper story although stars were also seen in large blockhouses. As can be seen in some of the illustrations in this book as well as in many other images, the variations were innumerable including some being made of stone to minimize the risk of being set on fire by a foe. Their outer defenses could be just a stockade or much more elaborate earthworks making them the strongest part of a redoubt. Blockhouses could also form the integral part of the walls of a frontier fort acting as turrets or be outside the curtain walls of a large work. The many purposes these buildings served explains their great popularity in North American warfare.

A lesser-known invasion attempt was aimed at Nova Scotia. In the fall of 1776, Jonathan Eddy led a party of about 200 American volunteers seeking to invade Nova Scotia in the hope that a substantial part of its population would join the Americans. This would take place by crossing the Isthmus of Chignecto that unites the mainland of Nova Scotia with what was then the northern boundary of Massachusetts. However, Fort Cumberland guarded the isthmus. The five-point earth and stone star fort, which had been built by the French as Fort Beauséjour, was captured and renamed Cumberland by the British in 1755; by 1776, it was run down, having been previously vacant for eight years. The fort was reoccupied in June that year by a detachment of the Royal Fencible Americans, a Loyalist unit led by Colonel Joseph Goreham, and repairs to the fortifications and barracks were carried out. From November 10, 1776, the Americans surrounded Fort Cumberland, but its loyal garrison would not surrender and it was besieged until November 29. That day, a British relief force landed nearby while Goreham and his men made a sortie from the fort; the Americans hastily retreated and Nova Scotia was secure for the rest of the war.

Most fortifications in Nova Scotia were located in the main settlement of Halifax, which was one of the Royal Navy’s most important bases in North America due to its strategic location. During the war, the existing fortifications built since 1749 were strengthened. The earth and timber citadel on the hill dominating the town was enlarged to an irregular, elongated polygon plan measuring about 1,300ft long by 430ft wide. It was armed with up to 100 guns, and its highest part was crowned with a square redoubt enclosing an octagonal blockhouse. It was further surrounded by a ditch and pointed stakes. There were also several large batteries that covered the harbor’s entrance.

Halifax harbor fortifications, 1780. The citadel with its square redoubt is at the upper center; batteries are on the south side (left and center) and the town is enclosed in a square palisade. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington)

An unusual raid took place on Hudson’s Bay, northern Canada, in 1782. The first target was Fort Prince of Wales, a masonry bastioned work built since 1731 by the fur-trading monopoly Hudson’s Bay Company, mounted with 42 cannons. During the 1690s, the French had raided and taken many trade forts, and this fort, located at the mouth of the Churchill River, was meant to be their protective citadel. On May 31, 1782, Le Sceptre, a 74-gun ship of the line, with two 36-gun frigates under the command of Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse, who was destined to become one of the great explorers of the South Pacific, sailed from Haiti. On board were 250 infantrymen and 40 gunners. On August 8, the squadron reached Fort Prince of Wales. The French troops landed and the bemused fur traders surrendered the fort (without a regular garrison) at the first summons. Lapérouse then sailed for forts York Factory and Severn, which also surrendered without a fight. All the forts were blown up and the French returned to Haiti. The economic damage was such that the company could not pay dividends for two years thereafter.

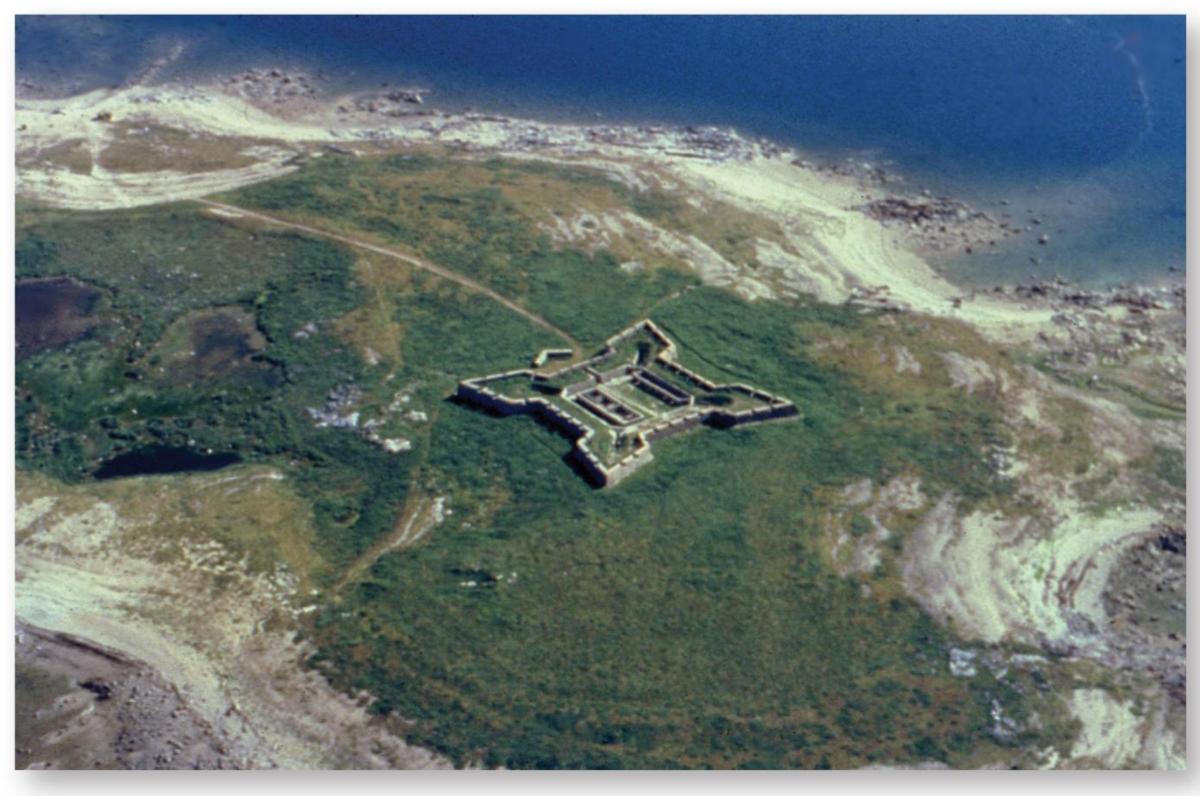

Fort Prince of Wales, Hudson’s Bay, Canada. This masonry fort is truly extraordinary due to its location at Churchill (Manitoba) on the shores of Hudson’s Bay facing the Arctic Ocean. Built laboriously from 1731 by the Hudson’s Bay Company, it surrendered to Captain Lapérouse’s French naval squadron in 1782. (Courtesy National Historic Sites, Parks Canada)