THE SOUTH

The first siege of Charleston, 1776

The British government had instructed its forces in America to occupy the southern colonies of Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia so as to bolster the loyal portions of their population against their rebel neighbors. On June 1, 1776, a British fleet including 11 warships with 3,000 troops aboard was in sight off Charleston, South Carolina, with the purpose of occupying the South’s most important city and harbor. This expeditionary force was under the command of Admiral Sir Peter Parker, whose flagship was the 50-gun HMS Bristol; General Clinton commanded the troops. Charleston was, however, a strongly patriot city and since March, anticipating a British intervention, its authorities had bolstered the city’s defenses by building various entrenchments mounted with about 100 cannons. Most efforts went into building a large square fort with bastioned corners on Sullivan’s Island to block ships going into Charleston’s harbor.

Detail from “A Plan of the attack on Fort Sullivan, near Charles Town in South Carolina by a squadron of His Majesty’s ships” on June 28, 1776 – a print after Thomas James. At top is a plan of the face of the fort with its “Retired Battery” extensions on each side. At bottom is an area map showing the fort and the attacking ships. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington)

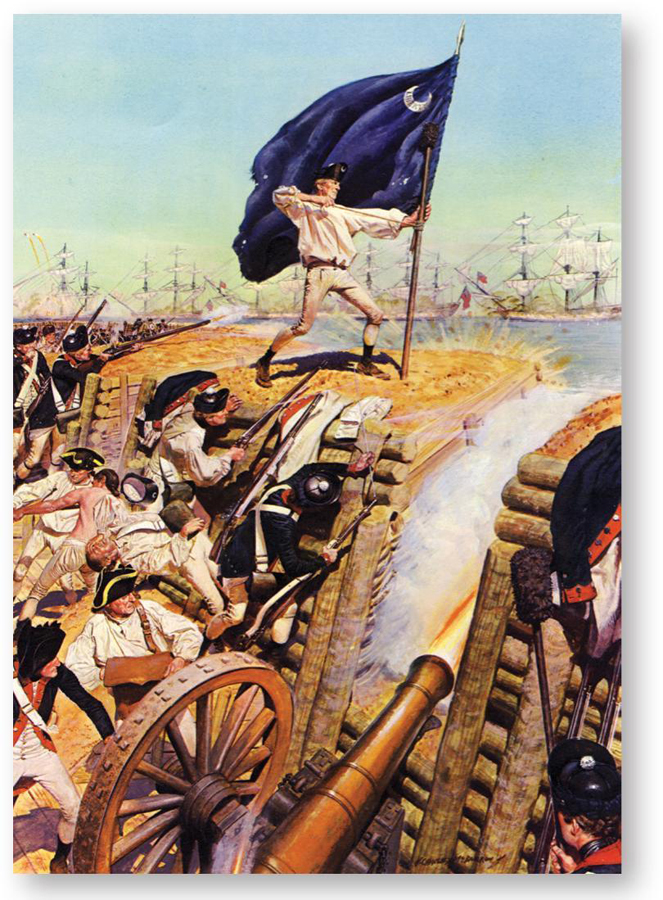

Once anchored off Sullivan’s Island, the British commanders spent nearly three weeks debating how to attack the fort. At length, the British troops under Clinton landed on marshy ground on Long Island. They were expected to cross a shallow sandbank at low tide onto the north end of Sullivan’s Island, overrun a small redoubt with two guns, and take the fort at bayonet point. Meanwhile the fleet would quickly shatter the walls of the fort. On June 28, the ships moved towards the fort. The American gunners held their fire until the warships were at point blank range, then opened very effective fire. The Royal Navy return bombardment was also very intensive, but both sides realized that this fort was robust and remained hardly damaged. It was built of “palmetto logs and filled in with earth, our merlons were 16 feet thick, and high enough to cover the men from the fire of the tops,” recalled Colonel William Moultrie, its commander. He further added that its “gate-way, (our gate not being finished) was barricaded with pieces of timber 8 or 10 inches square, which required 3 or 4 men to remove each piece.” The softwood logs of local palmetto trees were placed in parallel lines, as in the classic construction of earth and timber walls, and they filled the 15¾ft space between with sand. As it turned out, the resilience of palmetto wood made it much better than hardwood for resisting artillery fire, the energy of the cannonballs being absorbed by its spongy nature. Another positive factor for the Americans was the tenacity and coolness of the 1,200 defenders and the highly professional artillery service they performed due to previous intensive training by two master gunners. On the British side, when the troops came to cross at low tide from the marshes, they were already much harassed by mosquitoes and now found that some of the passage was up to 7ft underwater; their assault was thus cancelled. The battle became solely an artillery duel and the ships were mercilessly raked, Admiral Parker’s flagship being severely damaged. After a duel lasting nine hours and forty minutes, the British ships withdrew. The frigate HMS Actaeon ran into a sandbank and was burned by its crew to avoid capture. The overall American commander, Major-General Charles Lee, had meanwhile mobilized thousands of patriot militiamen and pressed all hands to build field fortifications around the city which now contained about 5,000 defenders. Even if Fort Sullivan (also called Moultrie) had fallen, it was unlikely the British could have taken Charleston. In the event, the attacking force suffered 205 men killed and wounded while the Americans had 37 men killed and wounded. It was another American triumph, in good part due to the rebels’ remarkable talent for building good field fortifications and defending them courageously.

Inside the American fortifications on Sullivan’s Island, Charleston, June 28, 1776 – a print after H. Charles McBarron. During the British fleet’s bombardment, Sergeant William Jasper recovered the South Carolina flag that had been shot down and planted it on the parapet under intense artillery fire. His heroism greatly encouraged the American defenders in the partially completed palmetto log and sand fort on Sullivan’s Island. (Courtesy US Army Center of Military History, Washington)

Savannah

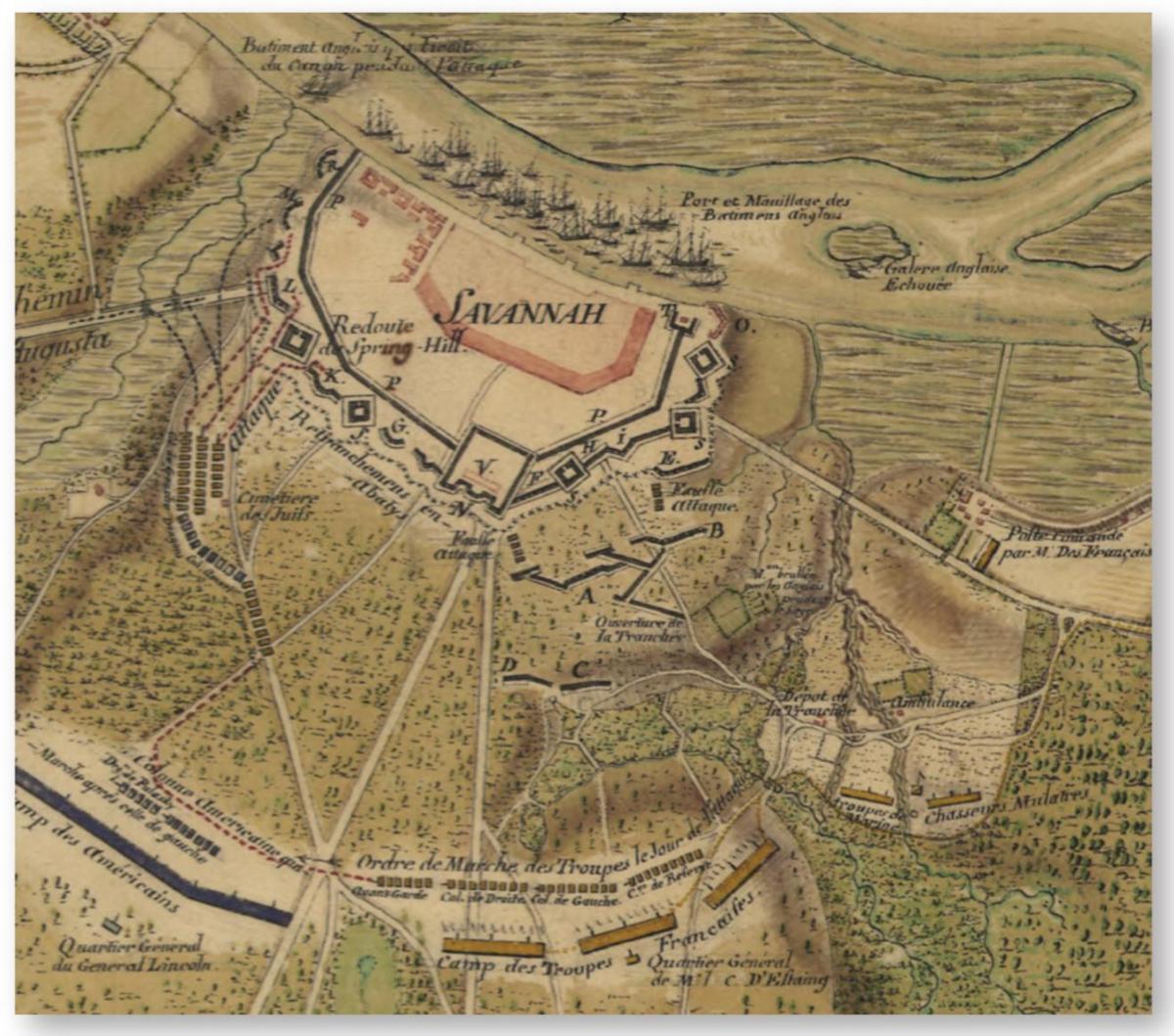

Following France’s entry into the war in mid-1778, Great Britain discovered that the newly reorganized and expanded French Navy was a transformed and efficient force that had little in common with the moribund fleet seen 20 years earlier. It now challenged, often successfully, the Royal Navy’s command of the sea in the West Indies, where British islands were falling to French sea and land forces. The Americans had not benefited much from the alliance, apart from seeing the occasional French squadron off their coast, such as Admiral Charles Hector, comte d’Estaing’s fleet’s short appearance off Newport (Rhode Island) in August 1778. Meanwhile, the southern states were becoming the main theater of the war. Savannah had fallen to the British at the end of 1778 and the American forces under General Benjamin Lincoln were hard-pressed. The following year, he asked for French assistance; the British fleet was on the defensive and d’Estaing’s fleet of 37 ships bearing 4,000 soldiers appeared off Savannah. It landed the troops on September 12, 1779; they were joined by Lincoln’s 2,500 men on September 16. General Augustine Prévost, who commanded Savannah’s 2,400-strong British garrison, spurned d’Estaing’s summons to surrender five days later, and siege operations began. The French built trenches and batteries to the southeast.

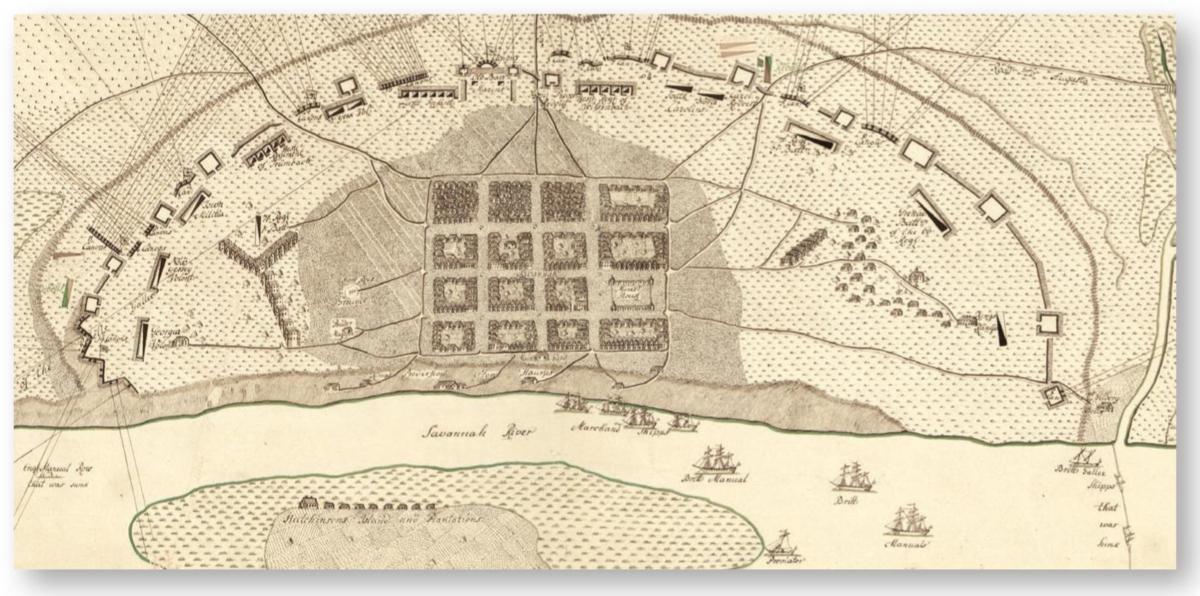

The fortifications around Savannah, August–September 1779, a detail from a larger pen and ink British map. The British Army built 15 redoubts and 13 batteries as well as many field fortifications along a crescent-shaped line that enclosed the city. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington)

Once the British determined to hold Savannah, its fortifications were greatly augmented in record time under the direction of engineer Captain James Moncrieff; a line of entrenchments with intervening redoubts was completed that now mounted about a hundred pieces of ordnance thanks to the unremitting labor of the troops as well as part of the town’s residents. It is said that the French engineers building their own siege trenches were impressed by the speed in which the English engineers made “batteries spring like mushrooms,” according to Porter’s engineering history. There were 15 redoubts and 11 batteries, large and small, with earth entrenchments in between, laid out in a wide arc around the city, in front of which was an outer line of abatis overlooking swampy ground. The French and American troops found the marshy ground difficult for building siege works. Parallel trenches were only completed on September 23 and Prévost caused much havoc when some of his troops made a sortie the following day. Work pressed on, however, and by October 3 the siege batteries opened fire. The unforeseen length of the operations increasingly worried d’Estaing: even though the threat of the Royal Navy intervening was receding, the hurricane season was approaching. On October 9, a Franco-American assault against two redoubts was repulsed with heavy losses, d’Estaing being among some 600 wounded; over 200 were killed in the assault party. The siege was raised nine days later; the French fleet sailed away, while Lincoln went to Charleston. Prévost had conducted a brilliant defense, making maximum use of the fortifications so hastily built around Savannah. In 1780 a curtain wall with small bastions was built to enclose the city and a small citadel, named Fort Prévost, was erected at its eastern end.

The siege of Savannah, Georgia, August–September 1779 – a detail from a larger French map by Pierre Ozanne. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington)

The fortifications at Savannah, 1782 – a detail from a larger American map. (Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington)

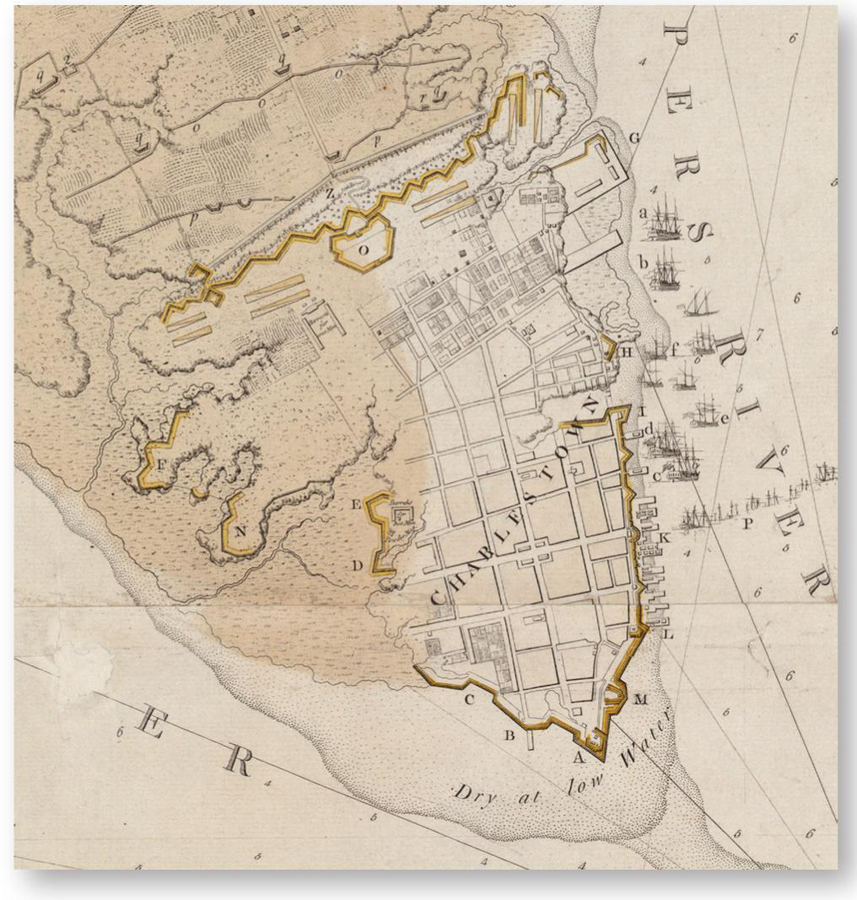

The second siege of Charleston, 1780

Emboldened by success, an 8,500-strong British force under Sir Henry Clinton arrived from New York to launch an overland attack on the city of Charleston, which was defended by General Lincoln’s 5,400 men. A further 5,000 British troops joined Clinton’s army. Siege operations began on March 29 and were carried out efficiently in the classic textbook manner. The British built small redoubts, establishing the first parallel from April 1; the second parallel was finished on the 19th and the third parallel completed on May 6. American defense works built across the northern portion of the Charleston peninsula consisted of a large masonry redoubt (or hornwork) made “to form a Citadel with strong Lines and Redoubts [on both of its sides], picketed and raised, covered by Trous de Loup, double Abbatis, a canal from Ashley to Cooper River, and Batteries mounting 66 Guns exclusive of Mortars,” according to the Sketch of the Operations at Charleston. Although these sounded formidable, the British drained the canal in early May by means of a sap and American senior officers knew that the works were, in fact, inadequate against such a strong force. The city surrendered on May 12. It was a serious blow to the Americans since the British now controlled the South’s main cities.

Charleston, South Carolina, 1780, in a detail from a contemporary map. This map shows the fortifications built to protect the city on its northern and eastern flanks. The older fortification lined the city’s shores on the Cooper and Ashley rivers. The defender’s citadel was a large redoubt built in the middle of the northern line (marked “O”) that was “picketed and raised, covered by Trous de Lous, double Abates, a canal from [the] Ashley to Cooper’s River, and Batteries mounting 66 guns exclusive of mortars.” (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Washington)

Ninety Six

Patriot resistance went on in rural areas with troops in constant movement in the interior of the Carolinas. The occasional field fortification was built and abandoned as troops moved on, but there were exceptions to this pattern. The most notable was the small village of Ninety Six occupying a strategic location in northwestern South Carolina. British Loyalist troops built fortifications there from December 1780, turning it into a stronghold. A stockade protected the village with a small redoubt at one end, but what made Ninety Six particularly strong was its unusual, eight-point star-shaped earthen redoubt erected by engineer Lieutenant Henry Haldane. Its walls were 14ft high and its ordnance consisted of three light 3pdr field pieces. The stockaded village and both redoubts were surrounded by an outer ditch and abatis. The star fort also had fraises protruding from its curtain walls.

By the spring of 1781, the Americans were winning in the South. After victories at Cowpens and Guilford Court House, General Greene with 1,000 men chose to attack Ninety Six, which had a garrison of 550 Loyalist troops led by Lieutenant-Colonel John Cruger. The star fort was its small citadel and it required a regular siege that began on May 22; under the direction of engineer Kosciuszko, trenches and parallels were dug and work also started on digging an underground mineshaft to blow up part of the curtain wall. A wooden tower about 30ft tall was also built for American marksmen to take out defenders on the walls. Cruger added sandbags on top raising the walls to 17ft that also gave good cover to Loyalist sharpshooters. Learning that a strong British relief force was approaching, Greene decided to storm both redoubts. At noon on June 18, a first assault group quickly overcame the smaller redoubt while a 50-man American “forlorn hope” rushed under fire into the ditch and started up the wall of the star fort. The latter were attacked by a sortie of 60 Loyalist soldiers, and retreated after desperate hand-to-hand fighting for the loss of 30 dead. The main attack had failed and the Americans also retreated from the small redoubt. Seeing this, Greene withdrew from Ninety Six before the British relief force arrived. The Americans had taken 150 casualties and the Loyalists nearly 100 during the siege. Ironically, Lord Rawdon, commander of the relief force, evacuated Ninety Six since its strategic value had become minimal due to operations elsewhere.

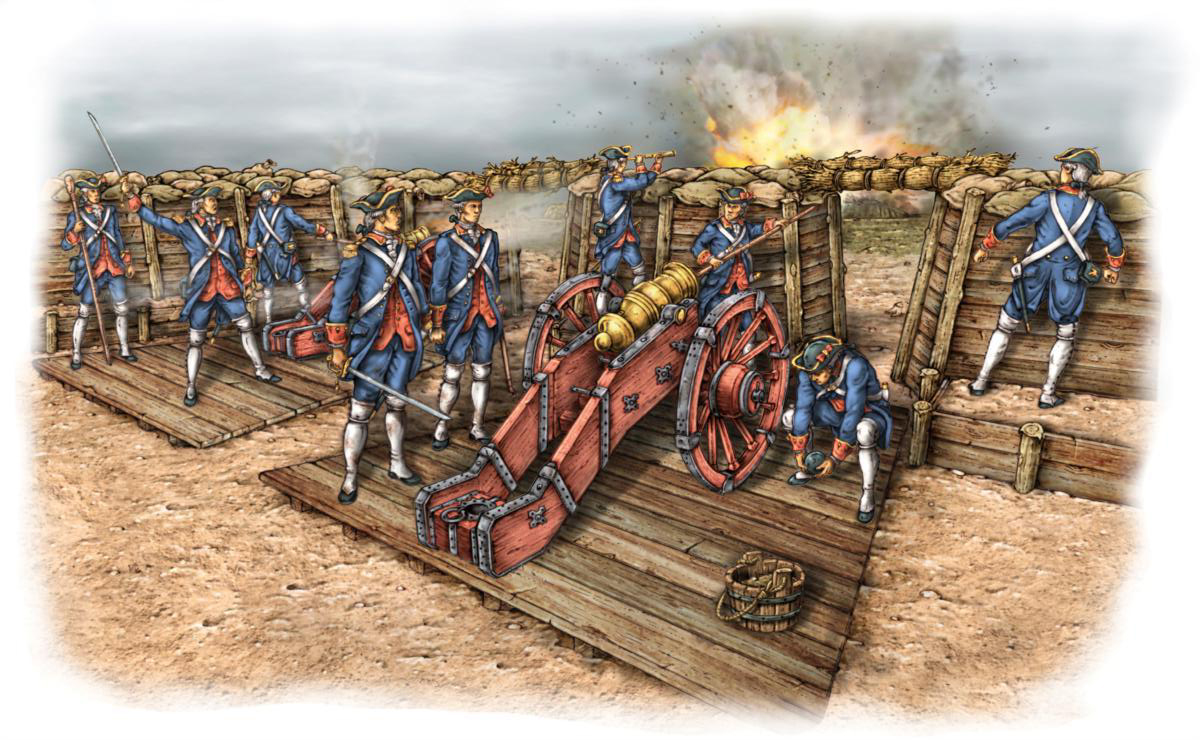

D SPANISH BATTERY, PENSACOLA, MAY 8, 1781

From March to May 1781, the Spanish forces besieging the British fortifications at Pensacola became more numerous as reinforcements arrived from the West Indies. By late April, the Spanish were applying standard siege procedures as they approached the powerful Queen’s Redoubt, which was the key to the British defenses. Although considerably outnumbered, the British put up a stubborn defense that included a successful raid on the Spanish advanced works. Nevertheless, by early May the Spanish were methodically moving closer and building trenches and a redoubt as well as batteries for 24pdr heavy guns to pound the British works.

On June 6, two howitzers were mounted in the redoubt; the cannonade between the opponents was intense for the next two days, but, by the afternoon of May 7, a Spanish forward battery was started and was nearly completed by five in the morning of the 8th. An hour later, the British opened fire, “to which we replied with two howitzers from the redoubts,” wrote General Gálvez, “with such success, that one of our grenades [howitzer shells] having fired the [British] powder magazine it blew up the crescent [the Queen’s Redoubt] with 105 men of the garrison.” Francisco de Miranda, then a young officer who would later become a liberator of Venezuela, recalled vividly that “we heard a great explosion … and we saw a great column of smoke rising towards the clouds.”

In terms of construction of siege works, Spanish engineers followed the same methods as their French allies and British opponents. The artillery they used was, however, of the older 1743 calibers and patterns since the Spanish version of the French Gribeauval system was brought into service after the war. Howitzer calibers were 7in. and 9in. At Pensacola, gun carriages would have been much as they had been since the 1740s. Their wood was often oil-stained although they could, at the time of the siege, also be painted red, grey, or black. The ironwork was black. Howitzers were of brass and featured a somewhat elongated breech. Spanish artillerymen were uniformed in dark blue with red collar and cuffs edged with yellow or gold lace, gold buttons, and gold-laced hats with red cockades.

West Florida

At the time of the American Revolution, Great Britain ruled over East Florida (with its powerful stone fort at St Augustine) and West Florida, which stretched from Pensacola to the eastern shore of the Mississippi River. Fort Condé, built with bricks and tabby (an oyster-shell concrete) by the French at Mobile, was the most extensive fort in West Florida; it was renamed Fort Charlotte in honor of Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the wife of King George III. Fort Charlotte was not considered an important post by the British and was in some disrepair (see Fortress 49: The Spanish Main 1492–1800 and Fortress 93: The Forts of New France). Other more remote places, such as Natchez, had relatively modest works consisting of simple stockaded enclosures or redoubts. For instance, the “field redoubt” near Baton Rouge named Fort New Richmond was described by the Spanish as “well fortified, with a ditch eighteen feet wide and nine deep; walls high and sloping, encompassed by a parapet adorned with chevaux-de-frise, crowned with 13 cannons of a large caliber” (Gazetta de Madrid, January 14, 1780). For its part, the enormous but largely unsettled part of French Louisiana west of the Mississippi River had been ceded to Spain during the 1760s along with its capital, New Orleans, which had modest earth fortifications around it.

Following Spain’s declaration of war against Great Britain on May 8, 1779, Bernardo de Gálvez, the aggressive governor of Spanish Louisiana, led some 1,400 men, most of whom were militiamen, against British posts and quickly took the stockaded Fort Bute at Bayou Manchac, the field redoubt at Baton Rouge, and occupied Natchez in September 1779, thus eliminating enemy presence in the lower Mississippi Valley. Obtaining some reinforcements from Cuba, Gálvez next appeared off Mobile at the end of February 1780 with about 1,300 men. Mobile at this time was garrisoned by about 300 British regulars and militiamen. By March 12, the Spanish had invested Fort Charlotte and their completed siege batteries opened fire; their heavy guns soon made several breaches in the old walls and Mobile capitulated two days later.

Much further north at St Louis, a mixed force of between 750 and 1,500 British and Canadian fur traders and First Nations warriors attacked the town on May 26, 1780. Its defences consisted of a single stone tower 30ft in diameter and about 35ft high, with trenches between the tower and the river to the north and south of St Louis. The defences proved sufficient for a 29-man detachment of the Spanish Luisiana Regiment with about 180 militiamen to repel the attack. A simultaneous assault on nearby Cahokia was also repulsed by American troops led by George Rogers Clark. On January 12, 1781, a mixed Spanish-led force of Illinois volunteers and First Nations warriors took stockaded Fort St Joseph (at Niles, Michigan) by surprise and looted it before returning to St Louis.

Pensacola

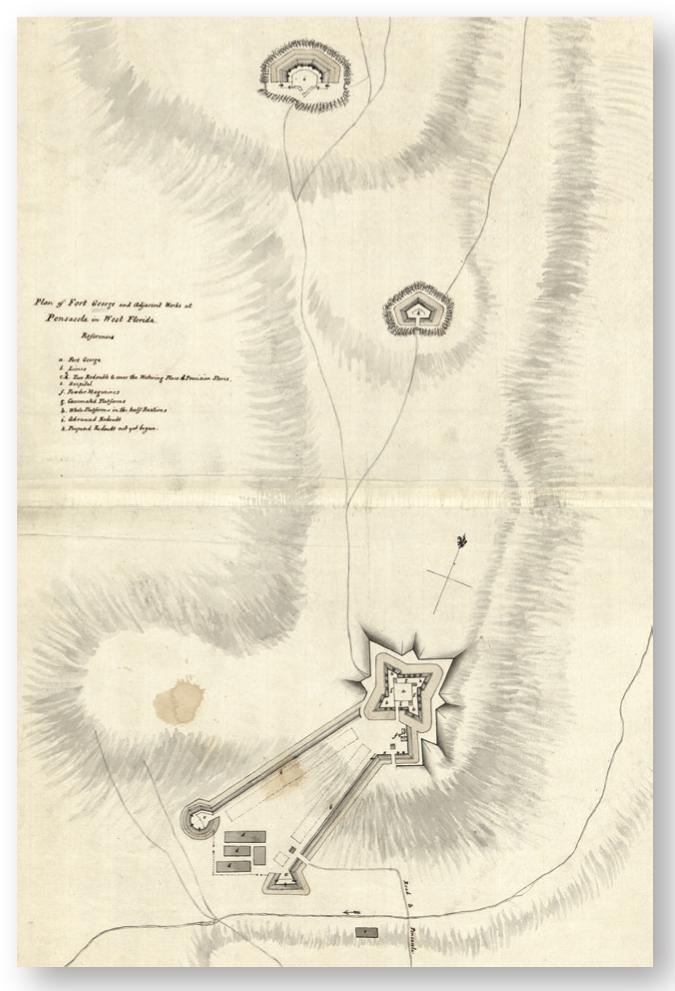

Pensacola, the capital of British West Florida, was the only major British post left on the Gulf Coast. Founded by the Spanish at the end of the 17th century, it had been occupied by the British from 1763. They first built a naval yard and replaced the crumbling Spanish fort with a “Garrison Area” that featured a large stockade with blockhouses, a redoubt nearby on the north side, and a ditch on the seaward side. The senior commanders in Pensacola knew the town’s few fortifications would be wholly inadequate against a powerful enemy force. A stronghold was needed and, during the 1770s Fort George – a large square redoubt with half-bastions and armed with 20 cannons – was built on the lower part of Gage Hill, about 1,200 yards north of the town. Fort George featured an elongated hornwork that extended some 600ft southwest, and it was sited so as to cover the town of Pensacola further south; a large work named the Queen’s Redoubt armed with 12 guns was erected on top of Gage Hill, so as to provide advance protection to Fort George from the north; another smaller fort, called the Prince of Wales Redoubt, was later constructed between Fort George and the Queen’s Redoubt to protect communications. The harbor’s entrance was guarded by Fort Barrancas Colorados (or Red Cliffs) armed with 11 guns. These works were made mainly of earth and brick since timber was scarce in Pensacola. Such as they were, these works provided Pensacola with a small citadel that might intimidate a modest hostile force, but was not likely to impress a numerous enemy army. Hopes for obtaining reinforcements from the British West Indies or from elsewhere in British North America were very slim and the Royal Navy was hard-pressed by the French and Spanish navies so that it no longer enjoyed naval supremacy in America.

The forts at Pensacola, West Florida, c.1780–81. At top is the Queen’s Redoubt, in the middle the Prince of Wales Redoubt, and below is Fort George, Pensacola’s command center for British West Florida. The latter featured an extended hornwork to the south. (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Washington)

On March 9, 1781, a Spanish fleet landed some 1,300 troops from Louisiana near Pensacola. Gálvez was again in command of the Spanish forces. There were some 1,300 British defenders under the command of Brigadier-General John Campbell in the three redoubts on the hill. Campbell knew this could only be the advance party of a much larger army and he resolved to put up as much resistance as possible. On March 18 and 19, the Fort Barrancas battery could not prevent Spanish ships led by Gálvez from entering the harbor, the indefensible town having been abandoned. During the following days and weeks, more regulars and militiamen arrived from Louisiana; everyone dug in, and opened siege operations in various parts of Gage Hill. They were joined on April 19 by a further 5,600 men from Havana and a detachment of over 700 French troops for a total of nearly 8,000 men. More scouting parties were sent out as the Spanish officers “had no exact plans, and the country was wooded,” wrote Gálvez. From April 22, more trenches were opened, one coming to within 600 yards of the British fortifications, and a sizable earthen redoubt named Fort San Bernardo was built as well as other smaller ones. Batteries with heavy guns, notably 24pdrs, and mortars were also built to pound the first target: the Queen’s Redoubt. By April 29, the Spanish had built long parallel trenches on each side of the British fortifications. There was constant artillery fire and frequent skirmishing. On May 4, at 12.30pm, the British “began a lively fire of mortars, cannons, and howitzers over the Queen’s Redoubt,” recalled Francisco de Miranda; meanwhile a party of about 200 soldiers made a sortie and took two Spanish advance redoubts, before destroying everything they could and withdrawing. As a result, the Spaniards reinforced their siege trenches and constructed a “wall of cotton bales and sand bags over the left wing of our [Spanish] parallel to cover the workers and to shelter the construction of the battery and cannons.” For instance, Gálvez mentioned some “700 laborers with 300 fascines, sustained by 800 grenadiers and light infantry” working through the night of April 26/27.

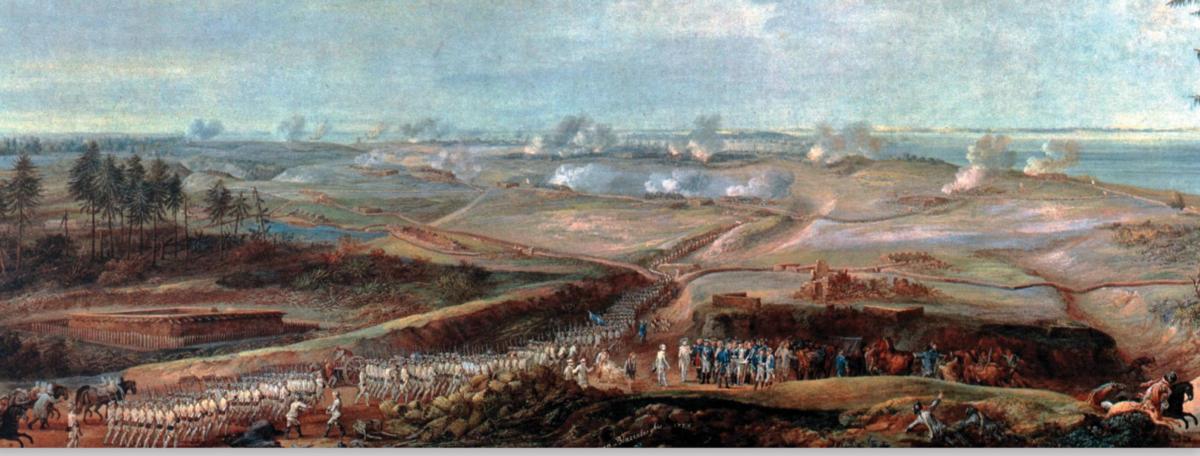

The capture of Pensacola, May 9, 1781. This print, after Lausan, was published in Paris after the war and seems to be based mainly on text descriptions. The works shown are liberal interpretations of written accounts, showing the explosion of the powder magazine. Troops wear French uniforms (with coat lapels, which the Spanish did not have) and General Gálvez (wearing a floppy hat) is certainly not taken from life, although his minor injury is shown by his left arm being in a sling. Although not dependable for detail, this work has artistic merit and appears to be the only near-contemporary illustration of the siege that has come to public attention. (Author’s collection)

French troops marching towards Yorktown in October 1781, in a work signed “van Blarenberghe 1784.” This is a composite view showing the abandoned British outworks in the foreground, the first and second parallel trench lines beyond, and the British works around Yorktown in the distance. (Courtesy Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library, Providence, USA)

Artillery duels also went on for days until May 8, when disaster overcame the British defenders. That morning, at 6.00am, the British opened fire from the Queen’s Redoubt. The Spanish replied with two howitzers and, at 9.00am, a howitzer shell penetrated the powder magazine causing it to explode “with a terrifying noise,” recalled Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis, killing 105 men. Spanish troops immediately rushed to occupy the badly damaged work and then turned its guns on Fort Prince of Wales; the latter’s guns were soon overcome and it “fell silent.” The garrison huddled in Fort George was now in a hopeless position and, on April 10, Campbell capitulated. The British lost 128 killed (including three officers) and 72 wounded. The Spanish suffered 94 killed (including ten officers) and 185 wounded. Although it had been a hard siege, and until the explosion occurred, the British had been well protected in their earth and timber redoubts while the Spanish attackers were in the classic siege situation of suffering higher casualties during the approach of their trenches. The casualties on both sides would likely have been much higher had there been an assault.

Although not immediately fully realized then, or later by some historians, the fall of Pensacola proved to be a tremendous blow to the British cause. Somewhat unexpectedly, Spain’s land and naval forces achieved total control over the Mississippi Valley and the Gulf Coast turning the northern Caribbean Sea into a Spanish lake. There was no point in attacking what British forces remained at the fortress of St Augustine, in British East Florida, since that territory now had a very limited strategic importance to colonial powers. Furthermore, the fall of Pensacola was to be of huge importance to the future role of the United States as a continental power. Within the following 40 years, all the territories in the Mississippi Valley and the Gulf Coast were ceded to the United States; this was the far-flung result initiated by the capitulation of Pensacola.

Yorktown

In July 1780, a 6,000-strong French Army corps under General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau arrived at Newport, Rhode Island, to act with the Continental Army under the supreme command of General Washington. This provided great encouragement to the Americans, and Washington was at first tempted to try to break the deadlock at New York; however, the idea came to nothing.

Meanwhile, the fighting in the Southern states took a turn for the better for the Americans from the beginning of 1781. Leaving Savannah and Charleston with British garrisons, General Cornwallis went to Yorktown, Virginia, arriving with his troops in late August. A new Franco-American plan emerged that called for a combined sea and land operation. Rochambeau’s army would come out of Newport and join Washington’s army outside of New York, and then the united force would march down to besiege Cornwallis in Yorktown; Admiral François de Grasse would come out of the West Indies with a powerful French fleet, land additional French troops to join the combined army, and keep Admiral Samuel Graves’ British squadron cruising off Virginia at bay. The plan worked and, in early September de Grasse, enjoying naval superiority, compelled Graves to withdraw to New York. The British forces in Yorktown could not be withdrawn by sea and were surrounded by a combined army of some 22,600 men, 8,600 of whom were French.

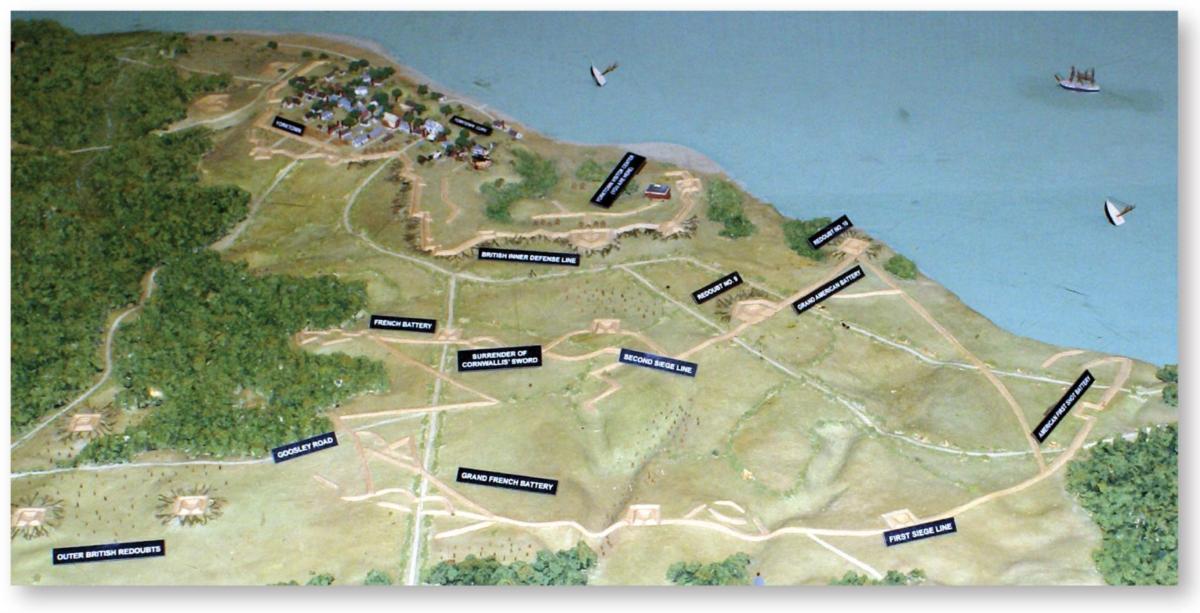

A model of Yorktown and the fortifications around it. In the foreground are the first parallel trenches with redoubts and batteries built from October 6, 1781, by the combined French and American Army. In the middle ground is the second parallel built from October 11–12 with, at right, numbers 9 and 10 redoubts incorporated in this line after their capture on October 14. At the center is the site of the surrender of General Cornwallis’ sword on October 19. Near the top is Yorktown surrounded by British works. Sunken British ships can be seen in the York River. (Colonial National Historic Park, Yorktown; author’s photograph)

Generals Rochambeau and Washington at the siege of Yorktown, October 1781, in a painting by Pierre Ganne after a work by Auguste Couder. As implied in this illustration, the technical aspects of the siege’s works were largely left – with Washington’s agreement – to the French Army, which had numerous and excellent staff and engineer officers, some of which are seen in this evocative canvas. General Lafayette is shown just behind Washington; a senior French engineer officer is at right pouring over a plan. (Colonial National Historic Park, Yorktown; author’s photograph)

Yorktown was situated on a point of land projecting from the southern shore of the York River, which created a narrow passage in conjunction with Gloucester Point on the north shore of the river. Both sides were occupied by British troops. Soon after they arrived, the British troops set about building a line of earthworks featuring ten redoubts around Yorktown’s landward side with an additional hornwork on the southwest flank that commanded the road to Hampton. Of the redoubts built, numbers 9 and 10 were outer works for additional strength built on slightly elevated ground south of the line of earthworks. Cornwallis was somewhat deficient of artillery and had to borrow guns from the few British warships in the river to arm the 14 batteries constructed along the line; they eventually mounted 65 cannons, but the highest calibre guns available were 18pdrs. A few outlying redoubts were built further away and a smaller line of earthworks with five redoubts also enclosed Gloucester Point.

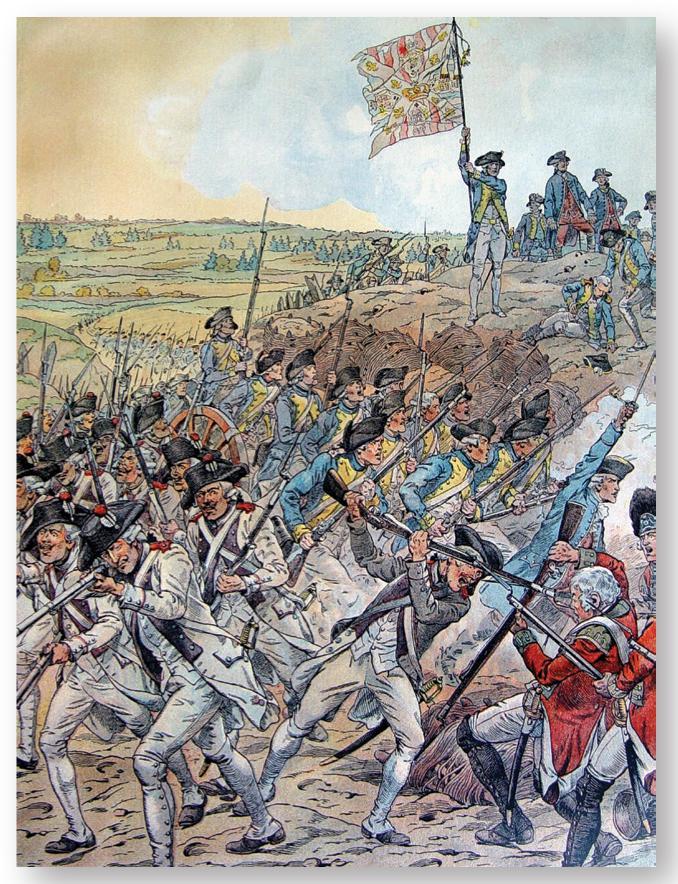

The French attack on the British Redoubt No. 9 at Yorktown, evening of October 14, 1781, in a print after Jacques Onfroy de Bréville in F. Trevor Hill’s Washington, The Man of Action (1914). At right is the Royal Deux-Ponts Regiment in sky-blue coats with an officer waving the regimental color; at left are the grenadiers of the Gatinois Regiment in white uniforms attacking with a cry of “Vive le Roi!” (“Long Live the King!”) Fighting was intense and the 400 attackers suffered 15 killed and 77 wounded; the Hessians and British counted 18 killed and about 40–50 wounded and prisoners. (Author’s collection)

In early October, the combined army arrived in the area. Gloucester Point was blockaded with field fortifications by Brigadier-General Claude de Choisy’s corps consisting of Lauzun’s Legion, half hussars and half infantry with 800 French marines and American troops. There was no intention of storming the point, but when Lieutenant-Colonel Banastre Tarleton with his British Legion cavalry did exit it on October 3, he was driven back in by the hussars led by Lauzun in person. The main army was meanwhile occupying the outer redoubts abandoned by the British, setting up camps, moving up the siege artillery, and surveying the area outside of Yorktown on the west side of the river. It was agreed that the terrain was suitable for a siege involving parallel trenches with earthen siege batteries. The siege artillery used by Rochambeau’s army consisted of 12 24pdrs and eight 16pdrs of the new artillery system introduced by Lieutenant-General Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval. It was the first deployment in battle of the Gribeauval system and proved to be very satisfactory. The four 8in. and eight 12in. French mortars were most likely of the older de Vallière design, still considered suitable for siege operations. The American artillery was more varied and numerous consisting of 27 18pdrs, three 24pdrs, ten 10in. mortars, two 8in. mortars and three 8in. howitzers for a total of 73 pieces of artillery for the allied army. On October 6, everything was ready and the building of the trenches by some 4,300 men for the first parallel started in the evening. By the morning of October 7, it was practically finished; this first line featured seven batteries and four redoubts, but it was only the preliminary work, which applied classic siege tactics as practiced in Europe on a scale rarely seen in America. By October 9 and 10, the French and American siege batteries started bombarding the British positions in Yorktown with heavy artillery including 24pdr guns and siege mortars, which poured a multitude of projectiles onto the town and also towards the few British ships in its harbor. British artillerymen did what they could, but they were outgunned and, from that date, their response became slower and more sporadic.

American troops storming and entering the No. 10 British Redoubt at Yorktown, October 14, 1781. This oil painting of the famous assault was made by renowned French artist Eugène-Louis Lami in 1840. It shows a remarkably good rendering of the redoubt’s profile with hand-to-hand combat all around. (Courtesy Virginia State Capitol, Richmond)

During the night of October 11/12, the trenches for the second parallel, which was only 360 yards from the British positions, were dug by thousands of men to a depth of 3½ft and a width of 7ft. To complete the line of this new parallel, the British redoubts numbers 9 and 10 had to be captured. On October 14 at about 8.00pm, as dusk was setting in, six howitzers fired in quick succession gave the assault signal. No. 9 Redoubt, which was the largest and had a bastion shape, was attacked by 400 grenadiers and chasseurs of the Royal Deux-Ponts and Gatinois regiments while No. 10 Redoubt, which was smaller and square, was assaulted by elite battalions of American light infantry. The British and Hessian soldiers put up a fierce resistance, but, after half an hour of epic fighting, both redoubts were taken. They were then incorporated into the attackers’ second parallel line, which was completed on October 17, bringing the British positions within point blank range of newly built French and American batteries. This put the defenders of Yorktown – which had already been under intense, round-the-clock bombardment for the past nine days – in a hopeless situation. Cornwallis and his officers knew it and asked for an armistice to discuss surrender terms. By then, the allies had fired some 15,437 rounds on the British positions, an average of a shot a minute round the clock since the start of the siege. On October 19, the British capitulated and a total of 8,091 surrendered. The allies had taken 389 casualties, the British and German troops perhaps as many as 904. It was the last major battle in North America, and from then on, it was obvious that Great Britain would lose the war.

E FRENCH MORTAR BATTERY, YORKTOWN, OCTOBER 1781

Mortars were arguably amongst the most dangerous pieces of ordnance to operate at that time. Bombardiers, the specialized gunners supervising mortar service, thus had higher pay and followed a precise procedure to minimize risks. Mortars were mostly used during sieges by both the defenders and the attackers. To load the mortar, in whose chamber a suitable powder charge had been inserted, it had to point straight up as shown here. A hollow, cast-iron spherical bomb filled with powder and debris with a fuse was then brought by two soldiers, hooked on a timber pole. The bomb was inserted into the mortar’s chamber on top of the powder charge. The bomb’s fuse was lit by a bombardier. The mortar was then aimed to its predetermined angle and fired by lighting its breech vent. If all went well, the bomb would fly in an arc trajectory and was timed to explode when falling close to its target.

At Yorktown, mortars were an important feature in the tactics of the allied army to subdue the town. A French plan shows that the second parallel, whose artillery fired at point blank range, included 16 mortars in two batteries. Probably all of Rochambeau’s 12 mortars (of 8in. and 12in. caliber) were mounted there. These were likely of the older Vallières pattern since the Gribeauval-pattern mortars were cast from 1785. The French mortars at Yorktown fired over 3,500 bombs during the siege. The allied army had great quantities of fascines, gabions, sandbags, and other items for erecting field fortifications as in Europe, as well as detailed building instruction for the troops.

The uniform of the Corps Royal de l’Artillerie (Royal Corps of Artillery) was then dark blue, including the coat’s collars, shoulder straps and lapels, with red cuffs, lining, and piping, and trimmed with brass buttons. Bombardiers were distinguished by two yellow chevrons worn on the coat’s lower left sleeve. The hat had black edging lace and the cockade was very likely the “alliance” type symbolizing white for France and black for the United States. For serving the guns, muskets and accoutrements were laid aside and some gunners might only have undress vests that were dark blue or white with red cuffs and forage caps. A “Roman” short sword was introduced for the men from 1775, but many probably still had the older model hanger with a “D” guard. Officers had the same uniform, but of better quality cloth and with gold buttons and epaulets.

F AMERICAN ASSAULT ON THE BRITISH REDOUBT NO. 10 AT YORKTOWN, EVENING OF OCTOBER 14, 1781

Earthen and wood redoubts, even as simple field fortifications, were very effective defense works that required great efforts to be overcome by the opposing force. Storming such a place could exact considerable sacrifice from an attacking force that, in spite of much heroism, might fail to take it. The classic assault force consisted of a forward party called the “forlorn hope” made up of elite soldiers, grenadiers, and light infantrymen with pioneers. The French Army called this party les enfants perdus (the lost children), which gives an idea of the survival rate expected. During the first years of the war, American troops were not trained in this type of action, but as time went by, they became more proficient in various aspects of European siege warfare as shown by the successful assaults of Stoney Point and Paulus Hook.

At Yorktown, 400 American light infantrymen under the command of Colonel Alexander Hamilton were tasked with assaulting Redoubt No. 10 held by 70 British soldiers while the French would assault Redoubt No. 9. On the evening of October 14, the assault parties attacked. The Americans silently surrounded their objective and moved up with unloaded muskets, so as to not alert the British, for a bayonet assault. This illustration shows what happened once they reached the ditch and struggled to climb up the parapet; pioneers hacked to cut away the row of pointed logs meant to hamper any attackers while those soldiers that got across the logs managed to fight their way into the redoubt. The British resisted fiercely with musketry fire and hand grenades, but the Americans quickly overcame them, losing only nine killed and 25 wounded – a remarkably low figure.