”The DNA study, combined with multiple strands of currently available documentary and statistical evidence, indicates a high probability that Thomas Jefferson fathered Eston Hemings, and that he most likely was the father of all six of Sally Hemings’s children appearing in Jefferson’s records. Those children are Harriet, who died in infancy; Beverly; an unnamed daughter who died in infancy; Harriet; Madison; and Eston. . . . The implications of the relationship between Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson should be explored and used to enrich the understanding and interpretation of Jefferson and the entire Monticello community.”

—Report of the Research Committee on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings,

Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, January 2000

”Barbara Chase-Riboud’s novel Sally Hemings … probably has been the single greatest influence shaping the public’s attitude about the Jefferson-Hemings story. . . . It was the book’s presentation of Hemings’s humanity, by telling the story from her point of view and giving her an inner monologue based on common emotions, that caused the biggest problem for Jefferson defenders. Hemings was portrayed as a person with actual thoughts and conflicts, giving her a depth of character seldom attributed to American slaves or to black people in general. She became real—and the possibility of the relationship became real—once she was taken seriously and presented as a full human being.”

—Annette Gordon-Reed, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings:

An American Controversy

THIRTY YEARS AGO, when my novel Sally Hemings was first published—this reissue is the anniversary edition—many things were very different from how they are today. My first book of poetry, From Memphis and Peking, had just been exquisitely and lovingly edited by Toni Morrison, my editor at Random House. Black studies was in its infancy in American universities, and the name “Sally Hemings” was totally unknown to the general public. Everyone involved with the novel, including the author, underestimated the emotion and controversy that would swirl around a story that gave flesh, blood, and sinew to the much-discussed contention that Thomas Jefferson had fathered a slave family by his mistress of 38 years, the half-sister of his dead wife. This belief had been long held, extending even to contemporaries such as John Adams, who received Sally Hemings and Jefferson’s daughter at the American embassy in London, and Gouverneur Morris, a New York congressman who was with Jefferson in Paris in 1789. And it had been long denied, by the Jefferson family, the president’s biographers (known as “the Jeffersonians”), and the entire historical establishment at large.

One cannot discuss the writing and original publication of Sally Hemings without also addressing this conspiracy of silence, which concealed the very existence of Jefferson’s mistress for over two hundred years, from 1788 to 1998. It was not only a matter of puritanism, patriotism, and establishment history; it was also a question of miscegenation—race mixing, which was prohibited by law as a felony in most U.S. states until the twentieth century. When my novel walked Sally Hemings through the front door of history, the country’s last miscegenation laws had been abolished only a dozen years before. Had Hemings been European, her history might have long since been written differently

I had wanted to illuminate our overweening and irrational obsession with race and color in this country. I would do it through the man who almost single-handedly invented our national identity, and through the woman who was the emblematic incarnation of the forbidden, the outcast—who was the rejection of that identity. And ultimately I would use the form of the nineteenth-century American gothic novel, whose very essence is embedded in the national psyche.

I do believe that if this story had not begun in France, where I have lived since the early 1960s, I would never have attempted to unravel the tangle of legend, symbolism, evasion, disinformation, hostility, and false perceptions of almost mythical dimensions that surround it. I don’t know that I myself would have believed the story of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings if it had begun in a field at Monticello, as many had chosen to assume, rather than in prerevolutionary Paris. And never knowingly would I have taken on the old-guard Jeffersonians, men with an agenda to protect the good name of Jefferson, by any means and at all cost, from their greatest fear—the accusation of race-mixing, or as it was misnamed around 1864, miscegenation, a term that originally had nothing to do with race but referred to the intermixing of heathen and Christian motifs.

It was the taboo of miscegenation—or as it was called by the Virginians, amalgamation—and the racist laws of the South that would have branded Jefferson an immoral pervert and a criminal. It was not the fact that Jefferson, a widower, had had a thirty-eight-year affair with a woman; it was that this woman was a quadroon slave and as such black in the eyes of the laws of Virginia. Persons who indulged in such crimes faced grand prejudice and ferocious punishment: fines, imprisonment, and possibly death. Many defied the rule, but Jefferson’s defenders could not imagine that he had been among the transgressors. The Jeffersonians protested that the charges were “defamatory,” “ridiculous,” a “lie” begun by a drunkard journalist in 1802 for political purposes.

As for Hemings, she was categorized as a “healthy prostitute” or jezebel, or a stereotypical slave a la Prissy from Gone with the Wind. I had therefore to find a way to elevate a member of the most despised caste in America to the level of the most exalted, in order to make believable Sally Hemings’s liaison with one of America’s most famous historical personages. Linguistically, I solved the problem by always referring to Sally Hemings by her full name. I felt that neither the author nor the reader had the right to call Hemings “Sally,” much as Hemings dares not call Jefferson “Thomas” until they are equal in love. This subtlety was sometimes lost on my copy editor, who wanted to know what difference it would make if a few “Sally’s” slipped in, but as far as I know, over thirty years (and counting), no one has commented on this styling and its effect—apparently, and gratifyingly, because the technique seems natural to readers. It simply lifts Sally Hemings well out of her role as a slave and helps make a minor historical figure the equal, as a genuine archetype, to Thomas Jefferson.

In writing Sally Hemings, I was determined to present a full-blown, complex, intelligent, highly conflicted woman—a tragic heroine who, trapped in the slave society that was the United States at its birth, clings to the only thing she can claim as her own: her love and allegiance to her “master,” her half-sister’s husband, and her father figure, Thomas Jefferson. I adhered scrupulously to the historical facts that offered any insight into the real Sally Hemings, including psychological studies of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Southern women, both black and white; their letters and diaries; the excruciatingly complex Hemings family tree; and the convoluted dynamics of Southern family relationships. And I anchored her story in the larger documented history of the period: the Declaration of Independence, the Jefferson-Gray letter, the “Notes of Virginia,” and the background of the French Revolution and Paris where it all began. I even made reference, in fictionalized form, to the real 1820 census taker who changed Hemings’s race from black to white.

I felt that this woman, with her passions, her loves, her dangers, her tragedy, her children, blood relations, servitude, and yearning for freedom, had lived a life so dramatic that very few fictitious inventions were necessary to portray her. Yet fiction was necessary to put “flesh on the bones” of a person who had literally been erased from history.

I also learned that fiction was the only form in which I could tell such a story, so vehemently did the Jeffersonians insist that I lacked the bona fides to touch Thomas Jefferson as a chronicler, being only a novelist (with a grudge). (As Toni Morrison wrote in “Romancing the Shadow,” “There is no romance free of what Herman Melville called ‘the power of blackness,’ especially not in a country in which there was a resident population, already black, upon which the imagination could play.”) As late as 1998, just two weeks before DNA tests by an unassuming retired Virginia pathologist named Dr. Eugene Foster proved the paternal genetic connection between Jefferson’s and Hemings’s heirs, the disparagement continued. The then-director of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, Gordon Wood, had already accused me of defamation and scandal mongering, and in an exchange of editorial letters in the New York Review of Books he now accused me of “shooting from the hip” and asserted that Sally Hemings had nothing to do with Jefferson. Two years earlier, Joseph Ellis wrote in his “Note on the Sally Hemings Scandal” that “within the community of Jefferson specialists, there seems to be a clear consensus that the story is almost certainly not true. . . . After five years of mulling over the huge cache of evidence … on the thought and character of the historical Jefferson, I have concluded the likelihood of a liaison with Sally Hemings is remote.”

I, too, had mulled over the same “cache of evidence”—which was anything but “huge,” but which was available to all, even me. I examined the facts, including Hemings descendants in three states, the 1801 electoral campaign and newspaper scandal, revelations of a Washington journalist in Jefferson’s employ (James Callender, who after exposing the story was found dead in three feet of water in Washington, D.C.’s Potomac River), and Jefferson’s own census of his “family.” I brought a new point of view to the analysis, taking into account the long and suppressed history of miscegenation in the United States, the oral history of blacks, the 1873 memoirs of Hemings’s son Madison, and eyewitness commentary from men like John Adams and Gouverneur Morris. I reflected on the families’ sejour in Paris, the fact that not only were Hemings and her brother legally free in France but also Jefferson himself was no longer constrained by the mores of a slave society. Above all, I considered the blood ties between the two families. Hemings was half-sister to Jefferson’s dead wife: Hemings’s mother had carried on a forty-year liaison with Jefferson’s father-in-law, John Wayles, and bore him six children, the youngest being Sally Hemings. I began the book with Elizabeth Hemings, putting her role as matriarch into the context of the American Revolution and slavery, and drew my conclusions about truth, love, race, and sex in America. I found that to Jefferson specialists, the idea of American history being influenced in any way by the relationship between the hallowed third president of the United States and his mixed-blood slave family was so repugnant that it trumped all obvious evidence to the contrary.

In 2000, when the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation published its white paper that confirmed the DNA findings and conceded that Thomas Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemings’s son Eston Hemings and probably, according to corroborating evidence, all of her children, I believed the famous argument settled and won. Yet since 2000, a new wave of Jefferson historians have continued to try to reduce Sally Hemings to an historical zero. Now that her place in history is confirmed, they trivialize its significance and whitewash their previous denial, claiming that they “knew all along” about the affair even as they dismiss Hemings herself as an “unknowable” figure.

This latest generation of Jefferson scholars is seeking a new virginity by denying the denial of those that challenged the conspiracy of silence—from Fawn Brodie’s seminal psychological study of Jefferson to my own “daring leap of imagination.” Whitewash? What whitewash? Where Sally Hemings was once dismissed as fiction, it is now co-opted into cant with footnotes. Thus my literature has become history by default, and as invisible as it was in the days when it was defamed to CBS as pornography and censored by Warner Bros. (see below).

The historical record, too, has been rendered inert. The research into Hemings and Jefferson has remained basically unchanged for the past thirty years, with no real breakthrough like recovering the only missing Jefferson letter register for the year 1788, spent in Paris; identifying the whereabouts of Harriet Hemings and her descendants; providing insight into the enigma of James Hemings’s suicide; or discovering any revealing letters by any of the female family members, such as Maria or Martha Jefferson or the Carr women. The only significant change is that the “family denial,” the accusation that Jefferson’s nephews the Carr brothers had fathered Sally Hemings’s children, has disappeared from the scholarship, thanks to the DNA evidence that disproved that possibility. The rehabilitation of Sally Hemings and her family is limited to the confines of parochial Monticello, instead of the larger warp and weave of American history.

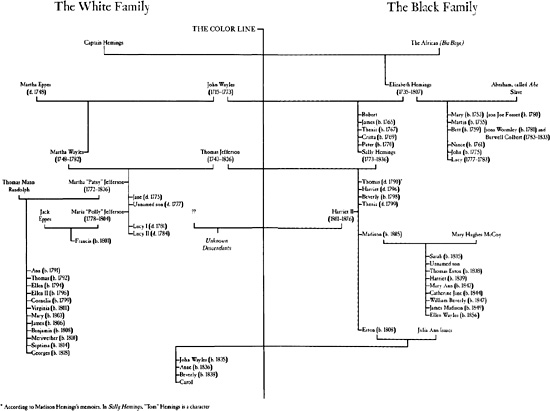

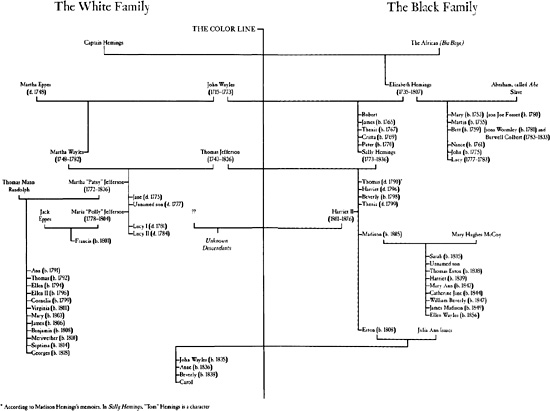

THE JEFFERSON-HEMINGS FAMILY TREE

Amazingly enough, there seems to be a particular reluctance to publish a unified family tree of the complete Jefferson-Randolph-Hemings family, as if the visual integration of the white and black families is just too much to bear. In her presentation, Annette Gordon-Reed reproduces only the Hemings family tree, and that only on the endpapers and nowhere else in the book. And in Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory and Civic Culture, which purported to be the results of a 1999 conference on the Hemings controversy, there is no family tree at all!

In the same book, Gordon Wood claims, ironically, that to rescue Hemings from obscurity one might need to look to fiction. He suggests that the works of the old Southern icon William Faulkner might hold the key to her mystery, even though Faulkner never wrote anything about Jefferson or Hemings—or, for that matter, anything about African-Americans before the Civil War that was not, as Ralph Ellison pointed out, “tinged by … patriarchy and paternalism.” “Faulkner,” Ellison also wrote, “really believes that he invented these characteristics which he ascribes to Negroes in his fiction and now he thinks he can end this great historical action [desegregation] just as he ends [Light in August] with Joe Christmas dead and his balls cut off … and everything, just as it was except for the brooding, slightly overblown rhetoric of Faulkner’s irony.” Here then was Wood, the stern scientific historian, suddenly yearning for interpretation from a novelist when he had railed for twenty years against Sally Hemings, the counter-narrative based on fact that had rescued Hemings from the trash bin of history.

When I first set out to tell the story of Sally Hemings, I envisioned it as an epic poem about a young slave girl in prerevolutionary France. I presented the concept to my Random House editor, Toni Morrison. She said she couldn’t get me any advance for the project as I had conceived it: “Random House wants a big historical novel.” I protested I was a poet—a sprinter and not a long-distance runner—and knew nothing of writing a full-length novel. I begged Toni to write it herself, but she was busy with her own projects. Then I asked every other writer I knew to take on Sally Hemings. Finally, my writer best friend said, “You have been going on about this woman for a year. Why don’t you just shut up and write the damned thing yourself! How long can it take? Three months of your life?” Instead, I dropped the entire project for over a year.

The book was saved by a chance meeting on a Greek island with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. During my family’s annual vacation on the Greek island of Speccia, a resort known for having no cars, no hotels, no tourists, and no public beaches, our hosts received their yearly invitation from Jacqueline, my friend’s old school chum, to come visit her on the Onassises’ private island of Skorpios, a five-minute helicopter ride away. For once, everyone accepted her invitation, and I found myself on what Jacqueline laughingly called “The Island of Dr. No,” explaining to the former First Lady the story of Sally Hemings, the former First Mistress. As a half-dozen speedboats with photographers behind telephoto lenses circled the island, we walked on the beach and talked about life in the glaring spotlight of power and fame, life in the back stairs of the White House, and those anonymous players who remain eternally in the background of history. Jacqueline was fascinated. “You must write this story,” she enjoined in her whispering, breathless voice. It was a turning point. I finally reopened my notes on Sally Hemings.

The project ended up taking me three years of research in the United States, London, and Paris. By the time I finished writing, Aristotle Onassis was dead and his widow had been hired as fledgling editor at Viking Press. She began by calling my agent every day until I turned in the manuscript. Sally Hemings was the first book she acquired as an editor for Viking, and it was never shown to any other publisher. For its part, Viking embarked on a series of perversities that threatened to derail the project. First, it assigned Jacqueline an editorial assistant who was an unreconstructed West Virginian: this woman claimed to “know how to handle these people,” referring to me, the only black writer in the house. (I remember distinctly that a large Confederate flag occupied the wall space in one of the editorial offices.) No sooner had I gotten rid of “the Virginian” (ironically, the title of the French edition of Sally Hemings), then Viking decided, over Jacqueline’s protest, to publish a thriller about a plot to assassinate a third Kennedy: Ted. When they went ahead with the project, Jacqueline quit, moving to Doubleday. She was not allowed to take Sally Hemings with her. Thus began a travail that seemed to have no end.

I remember huddling in a tiny room at the Algonquin Hotel in New York City with my writer best friend, rewriting. I insisted on paying my friend something for her professional services; I put a pile of greenbacks on the night table by the bed and said, “When these are gone, we’ve finished editing.” We spent a week incarcerated with room service and the manuscript of Sally Hemings.

Jefferson’s defenders got wind of the novel’s publication—and of the highly publicized sale of the movie rights to Warner Bros. Led by Dumas Malone, Jefferson’s major biographer, and Virginius Dabney, a Virginia journalist and Jefferson relative, they sprang into action, horrified not so much that the novel was garnering the kind of headlines, accolades, and editorials that rarely accompany a first novel, but that the Warner Bros. movie sale meant the general public would soon be privy to the Hemings secret, which the establishment could control in the academic world but not in the real one. They threatened Viking Press and proclaimed the story of Sally Hemings a lie, the invention of a deranged drunkard journalist named James Callender and a vengeful black woman with a grudge against Jefferson for what he did to her ancestors. They wrote letters of protest to the editorial page of the New York Times. They could not, however, find one error of fact in the entire book. Viking panicked nevertheless, cutting the publicity budget for Sally Hemings in half, reducing the full-page ad in the New York Times Book Review, and slashing the first print run of fifty thousand. The company’s publicity department issued a disclaimer that the novel was “a drama created by one black woman, not a historical treatise.” I was no longer Viking’s author or writer, I was merely black and a woman.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, the Jeffersonians also directed their “anti-defamation” campaign toward the president of CBS, Robert A. Daley, whose network had bought the movie rights from Warner Bros, and was already in production on a miniseries version of Sally Hemings. After the scholars dispatched intimidating letters and phone calls and threatened to enlist Virginia schoolchildren in a public letter-writing campaign, CBS chairman William Paley pulled the plug on the production historian Merrill Peterson had labeled “vulgar sensationalism masquerading as history.”

Even the staff at Monticello fought to keep Sally Hemings out of the public eye. They refused to allow a CBS News Sunday Morning crew onto the grounds to interview me, until CBS threatened to film in front of the gates and announce the obstruction on the air. But it was not until a later visit, in September 1979, that I discovered the true lengths to which they were willing to go to discredit the Sally Hemings story. I had returned to Monticello with a reporter and a photographer from People magazine. We decided to take the public tour and, to my great surprise, a tiny spiral staircase, which had been visible in Jefferson’s bedroom alcove ever since his house was opened to the public seventy years earlier, and which I had seen with my own eyes on a previous visit, was suddenly gone, and in its place was only a big gaping hole.

The strange tiny staircase had come to my attention during my research earlier in the decade, when I discovered it in a National Geographic photograph from the 1930s. In the photo, it was built into the alcove behind a narrow door at the foot of Jefferson’s bed, and an accompanying caption wondered if the “mysterious” staircase led to a bodyguard’s room overhead. Wanting to see for myself, I took the tour, waited until the guide had left the room, and ran up the narrow steps to discover a brick passageway that led nowhere and looked down on the room below. I decided to incorporate the staircase into Sally Hemings: in the novel, the staircase is hidden behind that narrow door, and the passageway with the three oval windows above is how Sally Hemings enters and leaves Jefferson’s bedroom without being seen by the plantation’s visitors and other servants. Readers began to come to Monticello to see the “Sally Hemings staircase.”

But now I found myself in Jefferson’s bedroom staring into the empty cavity of a torn-out staircase. In shock at such vandalism, I asked the guide, who had surely been there since the Flood, what had happened to it. To which she replied, “What staircase? I don’t know anything about a staircase,” trying to hide the unplastered hole with her thin body as the People magazine photographer clicked away. I stormed into the curator’s office, demanding to know why they had torn out the staircase. The reply was that I was being “paranoiac”; it had nothing to do with me. They had decided in February, they said, before the book was even published (but when it was already in circulation and review), to tear out the staircase because it was not “authentic.” What, I asked, had been there before? “Steps” was the answer.

Years later the screenwriter assigned to the Warner Bros. film project told me that he had been at Monticello on July 3, 1979, and the staircase had been intact. But when he returned July 5, the staircase had disappeared. It seems that on the night of July 3, a national monument had been defaced in a rage of destruction so that at the dawn of July 4, the anniversary of Jefferson’s death, there would be no trace of Sally Hemings to sully his memory.

Despite the Jeffersonians’ continued resistance, Sally Hemings went on to attract eleven more movie options, one that lasted only for a heated twenty-four hours.

The book was widely praised and reviewed to critical acclaim. The New York Times said it gave “new luster to the words ‘historical novel.’” It won the prestigious Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize for best novel by an American woman, which had previously been awarded to both Mary Gordon for Final Payments and Toni Morrison for Song of Solomon. It remained on the New York Times paperback bestseller list for six weeks, and sold over a million and a half copies nationally in paperback and hardcover. It was translated into nine languages and became a bestseller in France, Germany, and Italy; in France it remained on the bestseller list for sixteen weeks and sold over a million copies in eight different editions. In the United States it was a Literary Guild Book Club selection, which meant even more copies sold and more rave reviews.

Dumas Malone was so incensed by the Literary Guild Selection that he encouraged Virginius Dabney to publish a seething 250-page reply, The Jefferson Scandals: A Rebuttal (1981), attacking both me and Fawn Brodie, the Jefferson biographer who had first broached the Hemings affair, with everything they had including the kitchen sink. This despite the fact that Brodie had just died of cancer, harassed to death, I believed, by the infamous treatment she was subjected to as the historical community’s Benedict Arnold. The fact that she could no longer answer her detractors nor defend herself did not deter the gentlemen. The book was a convoluted and vicious tirade of disinformation. Whereas it left Brodie’s personal life alone, it defamed me in great biographical detail.

In 1987 I received a warning from a writer friend in Canada: a play was circulating in the United States that plagiarized Sally Hemings. I remember writing him that anyone could create a play about an historical figure (even one whom the official historical record had disavowed). But I got hold of the published play and was alarmed to discover twenty-four striking similarities to my fictional speculation.

In 1990, representing myself, I began an almost two-year federal court battle over Dusky Sally that led to a landmark copyright decision. In a twenty-six-page judgment, Judge Robert Kelly found that “the similarity between the two works is so obvious and so unapologetic that an ordinary observer can only conclude that Burgess felt he was justified in copying ‘Sally Hemings.’”

Just as I had hoped, the 1991 landmark ruling became an important part of copyright case law. It established that creative inventions and fictional elements incorporated into historical novels and plays are afforded the protection of copyright. As Judge Kelly put it in his decision, “It is one thing to inhibit creativity and another to use the idea-versus-expression distinction as something akin to an absolute defense—to maintain that the protection of copyright law is negated by any small amount of tinkering with another writer’s idea that results in a different expression.” At a time when “docudrama,” “faction,” or “fictory” has become a literary genre (thanks in part to Sally Hemings), my victory provides protection for many other writers in America.

In 1994, I returned to Hemings, Jefferson, and their children in The President’s Daughter, published by Crown/Random House. I dedicated it to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who had died earlier that year. Her words still resonate in my mind: “Even though people may be well known, they hold in their hearts the emotions of a simple person.” That was the guiding principle in my quest to solve the multiple enigmas of Jefferson and Hemings, and in The President’s Daughter I took the inquiry one step further, exploring identity, ethnic confusion, and the dilemma of passing for white. I also expanded on the original novel’s account of the lives of Eston and Madison Hemings, based on what had since been published about their lives after Monticello.

This was my Civil War novel, and in it I dared to address the “tragic mulatto” archetype from the historical point of view of Jefferson’s lost daughter Harriet. The title was an homage to William Wells Brown’s eighteenth-century abolitionist novel Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter, the first published novel by an African American, which dealt with Jefferson’s daughter as well, but not by name and with much greater melodrama. I invented a narrative life for Harriet closely correlated to the historic events of her life, which I projected into her old age, leading up to and including the Civil War. I put Harriet at Gettysburg with two great documents running in counterpoint in her head: her father’s Declaration of Independence and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. It is one of the most complex and best scenes I have ever written, and the book is my most cinematic novel.

Publisher’s Weekly said, “Like its prequel, this is lushly entertaining history-as-fiction, and just possibly fiction-as-history, that’s going to raise eyebrows—and probably hackles as well.” Which it did, once again. The President’s Daughter raised the same unanswerable questions and evoked the same inexplicable rancor as Sally Hemings, until an obscure Virginia scientist decided to challenge the limits of scientific historiography by testing the genes of Jefferson’s purported descendants both white and black to prove the truth or falsehood of the Sally Hemings story.

It was after the 1998 DNA study validated the historical claims behind Sally Hemings and The President’s Daughter that PBS aired a documentary on the controversy called Jefferson’s Blood, for which I was interviewed. As part of the documentary, the network also inaugurated a Web site on which they tested the DNA of famous people to determine their ancestors. There were many surprises. It was revealed that most free African American and biracial families descended not from a white master and a black female slave, as is commonly believed, but from a white woman and an African male. Historian Mario de Valdes traced Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s bloodlines back to the van Salees, a Muslim family of Afro-Dutch origin prominent in Manhattan in the early 1600s. And in the documentary, Professor Ira B. Berlin made a sweeping claim: “If any branch of one’s family has been in America since the seventeenth or eighteenth century, it is highly likely one will find an African or an American Indian ancestor.”

Genetics had not only vindicated Sally Hemings but also confirmed the broader truth behind it: that America’s racial history is more complex and hidden than most of us care to acknowledge. But in the wake of that vindication, the Jeffersonians began to deny their denial, and the new virginity of the erstwhile naysayers was forged. The accomplishments of Brodie and Chase-Riboud were purged in an effort to erase the embarrassing controversy of more than twenty years. I am the only one left standing to contest the establishment whitewash.

Even today, thirty years later, efforts continue to ignore and discredit Sally Hemings. I may be right, but never, ever right. When my Japanese translator visited Monticello for the fifth time in 2006 and asked to see the “Sally Hemings staircase” that I mentioned earlier, she was told not that it had been torn out twenty-seven years earlier because it was not “authentic”—but that it had never existed. She was taken up to the attic of the mansion and shown another mysterious staircase I had never seen nor imagined, and was told, “See, the staircase isn’t anywhere near Jefferson’s bedroom.” Astoundingly, a fake Chase-Riboud staircase had been implicated to replace the real Chase-Riboud staircase—which had been torn out because it was… “fake.” The translator dutifully transmitted this disinformation to the Japanese reading public in her notes, and what was gained? The dissemination of another lie casting doubts on the basic truth of Sally Hemings. Yet the tiny empty stairwell still exists at the foot of Jefferson’s bed. A corresponding staircase, I contend, should be restored as part of this national monument, and its ultimate meaning as a symbol.

Louisa Adams, who met Sally Hemings when she first arrived from Virginia, is quoted as having said in 1807, “Perhaps this is the first step towards the introduction of the incomparable Sally.” American history is full of these little pockets of invisible, usually unbelievable stories. They constitute a precious part of our heritage because they explain many of the myths, contradiction, and suppressions of orthodox history. The time has come and gone when mendacity was acceptable in the name of “the greater good”—so that the status quo could be maintained at all costs and the conventional historical record could prevail to the benefit of our “betters” or our “superiors” or “white purity.” Orthodoxy is no longer exempt from being closely questioned and defied when myth comes into conflict with inconvenient truths.

Sally Hemings stands there. She stands there as the ne plus ultra of our fear of invisibility, our dread of failure, our avoidance of guilt. She stands there like our anxiety and our shame. She cannot be excised like the bedroom staircase or the slavery clause in the Declaration of Independence. She will not disappear at the denial of the denial. She must be recognized as a poignant, tragic, and irreducible enigma at the very heart of the Jefferson myth. Reconciled to each other, they represent a small hidden core of American history, the heart of darkness in the American identity. If Thomas Jefferson offers himself up as a surrogate by which to meditate on the problem of human freedom, Sally Hemings is available for meditation on terror, darkness, and powerlessness. Even her whiteness is perceived as blackness.

Everyone knows that before history was proclaimed a so-called science, it was acknowledged as poetry. My “poetic” speculations took historical events and made them mean something, illuminating a literary heroine who is also history, a kind of real-life Natasha set against the war and peace of slavery. And now that this poetry has become “scientific,” I would like to think it to be a cause for celebration, or at least a kind of bemused respect. But only one newly “enlightened” scholar has made even a curt nod to the fact that Sally Hemings ended up on the right side of history. That the “incomparable Sally” escaped anonymity doesn’t mean she hasn’t left scores of others behind waiting for new truths.

My hope is that, with this new edition, my heroine’s final gesture will reverberate once more: She stood in her own embrace, triumphant; beyond love, beyond passion, beyond History. In my earlier drafts, Hemings died at the end of the novel, but Jacqueline protested, “There is no reason for her to die.” And so I allowed Sally Hemings to live beyond the novel—which she has truly done.

BARBARA CHASE-RIBOUD

For a PBS account of the Hemings debate visit “Jefferson’s Blood”:

www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/jefferson/