3

THE ANCIENT

ANGKOREAN

CIVILISATION

The world loves a good mystery, especially if it is an ancient one. Ancient Egypt provided the ‘riddle of the Sphinx’. Religious zealots have claimed the antique cities of the Americas were the work of extraterrestrials. The temples of Ancient Angkor—the largest ruins in the world and the only archaeological site visible from outer space—have presented their own share of riddles and these have prompted fanciful explanations for generations of visitors and readers.1 The novelist Pierre Loti wrote in the first decade of the 20th century of Angkor as a remote place steeped in impenetrable mystery: nothing could be known about the purposes of the ruins, a brooding, unfathomable Other. Even the age of the city was exaggerated in many accounts.

The French naturalist Henri Mouhot is supposed to have ‘discovered’ Angkor by accident, allegedly whilst chasing butterflies in the jungle—a claim he himself never made as he was guided there by a French priest, Father Sylvestre. Another French missionary, Father Bouillevaux, had left an account of an earlier visit and Mouhot was aware of this. When questioned about Angkor’s origins, Khmer peasants said giants built it. Europeans commonly believed that the builders belonged to a ‘vanished race’. Others claimed that the city was of Indian, Roman, or even Italian origin, alleging common features with Mediterranean architecture. Victorian etchings depict intrepid Frenchmen in tropical whites and sola topees treading resolutely amidst broken masonry festooned with the roots of giant trees. So potent was the image that people reacted with horror when archaeologists of the École Française d’Extrême-Orient began to clear the forest and restore the temples. Even today, the root-bound ruins of Ta Prohm pander to this taste for the ‘exotic’.

The truth about Angkor is rather more prosaic and yet, on another plane, more fascinating, because it is a story not of giants or extraterrestrials, but of people just like us. The ancestors of today’s Khmers built Angkor and the temple complex of the Heritage Area as the centre of a powerful empire and of a dispersed city with between 700 000 and one million inhabitants; it was the most populous city of antiquity, sprawling over an area of 1000 square kilometres or more. Today, in the elegant words of George Coedès, we see only ‘the religious skeleton of the city’, for the humble peasant dwellings and the richly decorated pavilions of the kings have long since rotted into the earth. The city was abandoned rather later than the romantics would have us believe and there is firm epigraphic and bibliographic evidence that it was still inhabited in the 16th century when Iberian monks first visited Cambodia. Although there is lively debate about a number of features of Angkorean civilisation, recent technological advances have enabled archaeologists to provide plausible answers to the puzzle of why the city was deserted. Although it is likely that a number of interlinked causes contributed to the collapse of this great civilisation, perhaps the most important was ecological degradation of the forests, water and soil. The fate of Angkor is a warning to the modern world that we are part of nature and must live within natural laws or face our ecological nemesis. If I have mentioned crocodiles more than once in this book, it is because I am aware of the ecological changes that have greatly reduced the numbers of this awesome, yet vulnerable, creature in Cambodia.

Sources of information

Thanks to the painstaking work of generations of archaeologists, philologists and other scholars, we now know a great deal about the society that built Angkor and the other architectural marvels of Cambodia. The ruins themselves are the most obvious record of Khmer material culture, and the bas-reliefs of the Bayon and Angkor Wat provide an extensive pictorial record of Khmer society. These illustrate the everyday lives of the people and the deeds of the rulers. They show how the inhabitants made war, fished, farmed, sold their merchandise, played games and erected the great monuments.

One problem has been that, unlike other ancient civilisations, the Khmers have left us no books. When H.G. Wells’ fictional time traveller ventured far into the future, he found the ragged remnants of the books of a long-dead civilisation within the solid walls of an ancient library. The ancient Khmers had libraries, but the books have vanished. The Chinese chronicles provide a record of the world’s longest civilisation and the ghosts of the Romans, Greeks and Indians speak to us through the pages of their books. The Irish have the splendidly illustrated Book of Kells, which dates almost exactly from the time at which Jayavarman II founded Angkor. The Dead Sea scrolls are even older, dating from the first century AD, a time when thousands of miles away on the other side of Asia, the Funanese had begun construction of their towns and libraries and canals. The soft Irish climate and the dry desert air have been kinder to paper and papyrus than the tropical heat, humidity and voracious insects have been to the palm leaf books of the ancient Khmers.

There is only one written eyewitness record of Angkor, The Customs of Cambodia, written during the late 13th century by the Chinese traveller Zhou Daguan (Chou Ta-Kwan), who spent a year in the capital shortly after the death of King Jayavarman VIII, the last great builder of Angkor. The country appears to have been completely unknown to Europeans. The great Venetian traveller Marco Polo visited neighbouring Champa in 1288, and the peripatetic Italian friar Odoric of Pordenone wandered through Indochina in the 14th century, but neither mentioned Cambodia in their accounts of their travels. When Iberian travellers arrived in Cambodia roughly two centuries after Odoric’s visit to Champa, Angkor’s glory days were past, and the city was menaced by its powerful neighbours, Siam and Vietnam.

The Khmers of course did leave a written record, but it was carved in stone rather than written on paper. There are around 1200 stone inscriptions in the Angkor region, written in either Sanskrit, Khmer or, from the 13th century, in Pali, the sacred language of the Theravada Buddhists. Most of the Sanskrit inscriptions are prayers to the gods or to Buddha, or tell us the genealogies of the kings, ruling families and Brahman priests, together with praise of their putative good works and military and civic virtues.

While the Sanskrit inscriptions are an invaluable record of the religious life of Angkor, the Khmer epigraphy tells us much more about the everyday lives, customs and occupations of the people. The epigraphs tell us a great deal about the earthly city, the empire and the complex and hierarchical system of administration. They show that Angkor was a highly literate society, at least among the elites, and that those who wrote the inscriptions had a lively sense of style, with a love of puns and figures of speech and an appreciation of tragedy and comedy.

However, much of the literary treasures of Angkor perished when the frail materials on which they were written rotted to dust after the city was abandoned. Between them, the sources allow us to understand much about a society that was once held to be impossibly mysterious. Yet the sharp edges are blurred, the voices are muted, and we see this civilisation through a glass darkly. There are murky lacunae in our knowledge and perhaps our explanations of Khmer society might still come under challenge in the future as fresh evidence emerges with the new archaeological tools of aerial and satellite photography, radar imaging and radiometric dating. There are some heated debates about Angkor, particularly around the archaeologist Bernard-Philippe Groslier’s ‘hydraulic city’ hypothesis, yet as another French archaeologist Christophe Pottier has cautioned, we should ‘put aside theoretical dogmatism’ until more facts are in.

Why was the capital moved?

The founder of Angkor, King Jayavarman II, is a shadowy figure and we still have no entirely satisfactory explanation as to why he moved his capital from the Mekong Valley to the drier region at the north-west tip of the Great Lake. He left no inscriptions that we know of. We know that he established his court in the region in 802 AD and that he reigned for almost 50 years before his death at Roluos, south-east of the main complex at Angkor.

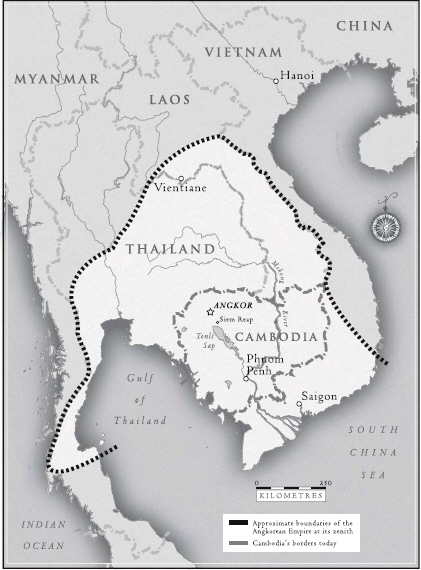

The Angkor region was not virgin land when Jayavarman II arrived. Archaeological evidence shows that the land between the Great Lake and the sandstone hills to the north was inhabited at least as far back as 1200 BC, with Iron Age remains at Phnom Bakheng. Probably, there were small farming settlements in the region ruled over by petty kinglets. Jayavarman II’s arrival was to transform the region. From his base at Angkor the king was able to unify the petty Khmer principalities into the single polity that was to become the centre of one of the most powerful, wealthy and populous civilisations in ancient history. At its zenith, Angkor was to control an empire that stretched from the South China Sea to the Isthmus of Kra and the Andaman Sea, and northwards into what is today Laos. As historians Ian Mabbett and David Chandler have pointed out, many of the subjects of this vast empire lived at remote distances to the capital city; even if they had obtained permission to travel, an elephant journey of only 50 miles from Battambang to Angkor would have taken five days, as it still did in the 19th century. This was no nation-state, but a multi-ethnic empire in which one ethnic group, the Khmers, was dominant. The core of the kingdom was the dispersed metropolis of Angkor—larger than Rome or any of the ancient Chinese cities, if we are to believe the most recent archaeological evidence—and Angkor was a Khmer city.

King Jayavarman II’s restlessness did not end when he moved his court to the Great Lake region. During his reign he would build three capitals, abandoning each before he made his final choice at Roluos. Regarding his move to Angkor, Michael Vickery has suggested that it resulted from military and political pressure from the hostile kingdom of Champa. Angkor was also remote from the coast of the South China Sea—and seaborne enemies such as the Javanese—with access hindered by the numerous sandbars and treacherous currents of the Mekong delta. At that time, too, the Siamese threat to the west did not exist. Other writers have suggested that the lake region was the ‘natural centre’ of the Cambodian state, at the junction of roads linking the valleys of the Mekong and Menam, at the highest point of navigation upstream from the Mekong delta, with ample supplies of sandstone for building, rich in natural resources such as timber and fish, and with fertile soil to grow rice to feed a growing population.

Yet although Cham, and perhaps Javanese, hostility might well have contributed to Jayavarman’s decision to move his capital to a more defensible site, the other explanations noted above are not very convincing.2 The English writer Christopher Pym argues in his excellent book on Angkor that the current capital, Phnom Penh, lies at a more commanding site, the Quatre Bras. Moreover, it is likely that the land routes were only developed after the foundation of Angkor, and the most direct route between the Mekong and Menam valleys follows the path of the French-built railway through Battambang, to the south-west of the Great Lake. Nor is sandstone as close by as some writers claim. The Phnom Kulen quarries lie some 40 kilometres to the north of the centre of Angkor and the soils are not as naturally fertile as those in the Mekong Valley, although they are probably more fertile and less sodic and saline than those in many other parts of Cambodia. It is true that the Great Lake is an almost boundless source of the fish that, along with rice, is the staple of the Khmer diet, but fish are just as plentiful elsewhere in the lake and especially around the entrance to the Tonlé Sap River that drains it via the Plain of Mud into the Mekong at the eastern end. It is also true that there was ample timber close to Angkor for domestic buildings, scaffolding for construction of the temples and for fuel but, then again, much of Cambodia is equally well endowed with forest.

The relative paucity of inscriptions from the reigns of Jayavarman II and his son of the same name do not help us explain the move. Perhaps, as Pym sensibly argues, the move was sparked by Jayavarman’s desire to get out of the ‘centre of things’ in Southeast Asia by relocating to a remote site. However, one intriguing suggestion is that climate change might have contributed to the move. James Goodman, an engineer with an interest in archaeology, argued at a recent convention of Angkorean scholars in Japan that the move ‘coincided with a series of remarkable changes in global climate patterns’ associated with the Southern Oscillation Index (ENSO). The late eighth century saw the onset of the ‘medieval warm period’, with a ‘wet anomaly’ in Cambodia and ‘dry anomalies’ elsewhere on the Pacific Rim, including Java. The wet anomaly might have caused increased flooding in the lower Mekong Valley and delta, but would also have meant more humid, favourable conditions for agriculture in the seasonally drier regions to the north of the Great Lake. Angkor also lies on higher ground, normally beyond the reach of flooding. Goodman also speculated that the relative decline of the power of Java, Cambodia’s former suzerain, might have been due to the onset of the dry anomaly, which would have unfavourably affected Javanese riziculture, as it did other civilisations around the Pacific Rim. That such climate change did occur is attested to by analysis of the pollen record, but more research needs to be done to ascertain its contribution to Jayavarman II’s move.

The move did not mean emigration to a land of milk and honey. Settlement near the tip of the lake required strenuous labour before the virgin lands could become productive. Marshes needed to be drained, embankments built to stop floods and—as Bernard-Philippe Groslier argues—an intricate system of canals built for irrigation purposes, for if the climate were anything like that of the Siem Reap area today, it would have been one of six months’ rain and six months’ drought. The hydraulic system, however, was not started until after Jayavarman II’s death, when in 877 AD King Indravarman I ordered construction of the Indratataka, the ‘sacred pool of Indra’, a large baray or reservoir measuring 3.6 kilometres by 800 metres.

As we shall see, the question of whether Angkor depended on highly developed irrigation is a moot point. It seems likely, therefore, that the shift to the Great Lake region would have been due at least in part to religious imperatives; Cambodia was, and still is, an intensely religious society. As the Japanese scholar Yoshiaki Ishizawa has argued, the choice of site has religious symbolism for the Khmers, who took their cosmology from the Indians who believed that at the centre of the world was Mount Meru, surrounded by oceans and seas and walled off by the Himalayas. Khmers tend to build their temples on hills to reflect this belief; Angkor stood on higher ground and just as India has the sacred Ganges and the sacred mountains, so Cambodia had the Siem Reap River and the Great Lake, with Phnom Kulen and the Dangreks to the north. The decision to shift the Khmer capital to Angkor was probably caused by a variety of overlapping political, economic, religious and perhaps ecological factors. Short of raising Jayavarman II from the grave, we will probably never know for sure.

The kings, their temples and monuments

A passion for grand monuments marks the greater part of the six or seven centuries of Angkorean civilisation and this only abated with the

Angkor Wat showing the five towers. (Author’s collection)

spread of Theravada Buddhism, which spurned vanity and megalomania. Slaves, serfs and artisans expended the sweat of centuries on the sandstone mausoleums-cum-temples of the kamrateng jagat, the ‘lords of the universe’, who ruled over them. Scholars disputed the purpose of the temples for many years until in 1933 Jean Przyluski formulated his thesis, daring for the time, that Angkor Wat was both a temple and the tomb of Suryavarman II, and thus both a sepulchre and the centre of a funerary cult. The grand buildings of Angkor are at one and the same time funerary temples, mausoleums and tombs, the ‘distinctive glory of the Khmer Empire’ in the words of the celebrated French epigrapher George Coedès. Although those who ordered their construction have long since rotted into the soil, their monuments still bid us to ‘look upon my works, ye mighty, and tremble’, for the kings assigned to themselves the title of gods—devarajas—though they were ‘creatures of clay’ like the meanest of their subjects.

Marvellous though they are as architecture and works of art, the temples of Angkor are the reflection of the overweening egotism and peculiar religiosity of the hereditary rulers, for whom no sacrifice was great enough provided it was made by their slaves and willing subjects, whose warm blood and sweat could not outlive the cold stone they placed block on block in the exquisite confections of Angkor. Perhaps, when we gaze on these stupendous monuments, we should muse over their human cost. That said we should be wary of extrapolating modern attitudes and ideologies into the remote Cambodian past. For many free men—serfs at least—it was probably an honour to toil on the monuments for the glory of the god-kings; for many slaves, their condition was one legitimised by age-old custom, as natural as the setting of the sun. They had no words for freedom and liberty.

The purpose of these immense buildings had nothing in common with the great cathedrals of Europe or the grand mosques of the Muslim world. Nor were they like the modern pagodas of the Theravada Buddhists of Cambodia and neighbouring countries. Angkor Wat is, on the face of it, a temple dedicated to Vishnu, but the deity worshipped here is not the same as the ancient god of the Hindu triumvirate. Rather it is King Suryavarman II, the temple’s inspirer, who was seen in life as the incarnation of Vishnu. Hence, as eminent French scholar Paul Mus wrote, these buildings are not so much shelters for the dead ‘as a kind of new architectural body—a house of the dead but only in the same way that his body lived in it while still alive’. Even the numerous statues of Vishnu and Siva are dissimilar to most of their kind in India, for they have the features of the kings who were the earthly incarnations of the gods. The temples are the houses of the god-kings, the lords of the universe, immortalised in solid rock. They were not like pagodas, churches or mosques where the common people might come to pray. If they were ever admitted, it would only be to grovel at the feet of the mighty devarajas.

The monument building obsession began some years after the death of Jayavarman II’s son and successor, Jayavarman III; although these first two kings did leave some hilltop shrines and smaller monuments, they were dwarfed by later developments. A new king, Indravarman I, ordered the previously mentioned baray and also the Preah Ko and Bakong temples. Indravarman was succeeded in 889 AD by Yasovarman I, who built a new reservoir, the Yasodharatataka, with the Lolei temple on an artificial island in the lake. Yasovarman also ordered construction of the temple mountain of Phnom Bakheng, excavating the slopes of a hill to form a pyramidal structure surmounted by five central towers and 104 smaller ones. The 13th century Chinese chronicler Zhou Daguan says that a Khmer king is buried at Phnom Bakheng, and if this is the case it was both a temple and a mausoleum, as Przyluski speculated. During Yasovarman’s reign, engineers appear to have diverted the course of the Siem Reap River and built the large Eastern Baray, the latter fact attested to in an inscription in its northeast corner.

Subsequent kings continued the program of temple building and waterworks. In the tenth century, King Rajendravarman ordered the construction of a series of monuments, including the Pre Rup temple. The temple of Takeo dates from the reign of Jayavarman V in the final years of the tenth century. Suryavarman I, who reigned from 1002 until 1049, was responsible for the construction of the huge West Baray and a number of temples including Preah Vihar in the Dangrek Mountains. Suryavarman II, who reigned in the early part of the 12th century, ordered the construction of what is arguably the most famous of the Angkorean temples, Angkor Wat, the name of which is often confused with the city of Angkor itself because of its imposing beauty and scale. Suryavarman II’s successor, Yasovarman II, had the temple of Bakong built. Jayavarman VII, a Buddhist king who reigned during the last decades of the 12th century and the first two of the 13th, ordered construction of the temple of Ta Prohm and the first stages of the Terrace of the Elephants, along with the impressive Angkor Thom, dedicated to Buddha (not Siva or Vishnu as is commonly supposed) and extensive waterworks including the Jayatataka baray.

These public works—if such is the name for private edification at public expense—were augmented by more utilitarian infrastructure, footways, bridges, rest houses, hospitals, canals, reservoirs and embankments. The empire was administered and policed via a network of well-maintained roads, which also served for trade purposes. These roads often ran on stone causeways or earthen embankments, high above the floodplains of lakes and rivers, and well-engineered bridges spanned the rivers. Although the network fell into disrepair after the decline of the empire, some of it was re-opened by the French and is still in use today. One particularly imposing bridge, the Spean Praptos, crosses the ravine of the Stung Chikreng and is still open to traffic. Guesthouses were built at regular intervals along the major roads—22 between Angkor and Kompong Thom alone—for shelter and security against bandits who preyed on travellers. The wealthy rode in palanquins (hammocks slung between Y-shaped poles and carried by muscular servants), or astride horses or aboard tented structures on the backs of elephants. But the poor travelled in buffalo carts, much the same as they do today, or else they walked. During the six-month rainy season, boats were used for some journeys, as they were all year round on the Great Lake which lay to the south of Angkor, and along which Zhou Daguan travelled on his way up from the far-away delta of the Mekong.

The climax of empire

Jayavarman VII’s reign, between the late 12th and early 13th centuries, is regarded as the climax of the empire. Angkor stood at the centre of a vast realm that extended from the Andaman Sea in modern Myanmar to the South China Sea in today’s Vietnam, and far northwards into what is now Laos. Although it might have been ultimately constrained by what modern historians call ‘imperial overstretch’, Angkor’s expansion was checked by natural, rather than human barriers—seas, mountain ranges and impassable jungles. However, as George Coedès has written, the huge effort needed to carry out Jayavarman VII’s building program was an ultimately unsustainable drain on the resources of the empire. The empire also sustained vast numbers of unproductive people, including aristocrats and Brahman priests,

The Angkorean Empire

members of the religious orders and the royal family itself. An inscription translated by George Coedès recorded that the devaraja cult necessitated 306 372 ‘servitors’, who lived in 13 500 villages and ate 38 000 tons of rice every year. This does not take into account the immense amount of riches in the form of silver, gold, bronze and stone appropriated by the cult.

This empire was maintained by force of arms, often clashing with neighbouring peoples such as the Chams and later the Thais, both of whom were formidable opponents. In contradiction to the modern European stereotype of Cambodia as ‘the gentle land’, the Angkor bas-reliefs depict a warlike society. Men march in formation, armed with a variety of weapons including swords, lances, bows and arrows and clubs. Catapults are mounted on carts or the backs of elephants. Commanders canter on horseback while their men march past resolutely in grim processions. Elephants were also employed for cavalry purposes, their foreheads anointed with human gall which, as Zhou tells us, was drained from the bodies of hapless passers-by by men armed with special knives. Other scenes show naval battles, with unfortunates falling overboard into the jaws of the lurking crocodiles. On the other hand, an inscription at Ta Prohm extols Jayavarman VII as a ‘provident and compassionate ruler’ and perhaps not without cause. Although he was determined to bend the population to his will to make his mark on posterity in the form of huge temples and monuments, he also built 102 hospitals during his reign.

The last great spurt of building activity occurred during the reign of Jayavarman VII (1181–1219). These works included the construction of Ta Prohm, Banteay Kdei, Preah Khan, Banteay Chhmar and the magnificent Bayon. However, during the 16th century, when the first Europeans visited Cambodia, King Satha I carried out extensive renovations to monuments and the hydraulic system.

Building the temples

Visitors to the ruins often wonder how they were built and where the immense blocks of stone used in their construction came from. The Khmers certainly were ingenious engineers, but the construction program relied on the muscle power of tens of thousands of labourers. The temples are built of an assortment of materials—laterite, three different types of sandstone, and brick, some of which was rendered with stucco. The laterite was obtainable locally, but the sandstone was brought considerable distances from the Phnom Kulen quarries, where men cut it from the living rock with crowbars, chisels and fire. Many of the blocks weigh up to five tonnes, and the very largest include one of eight tonnes at Angkor Wat and another of almost ten tonnes at Preah Vihar.

In the past, observers have speculated that the blocks were dragged by elephants, loaded on ox carts, floated down the Siem Reap River from Phnom Kulen, or sometimes taken on rafts down other tributaries then across the lake and up the Siem Reap River to Angkor. While these methods are possibilities for the smaller pieces of stone, it seems unlikely they were used for the bigger blocks. Ox carts could not support the weight and elephants probably lacked the stamina needed to transport the blocks from the Kulen Hills, which stand approximately 40 kilometres from the temple sites. In 1999, an attempt was made to float stone down the river from the ancient quarries. It was concluded that this was an unlikely method; to move a five-tonne block would require an enormous raft built of 1000 pieces of ten-centimetre diameter bamboo. It is more likely that human muscle power was employed, with the largest blocks requiring the strength of up to 160 men, their task only made slightly less onerous by the use of wooden rollers, crowbars and rattan ropes. (Even today, heavy machinery is sometimes rolled into position using similar techniques, but for a fraction of the distance.) There is some evidence to suggest this on the Bayon bas-reliefs (upper gallery, east side), which appear to depict men hauling stone blocks with the assistance of rollers, although there is some damage to the bottom of the frieze, which leaves this interpretation open to question. This gruelling work in the tropical heat and humidity was more than likely allocated to the lowest grades of slaves. There was probably a more complex division of labour at the actual construction sites: general labourers to supply raw muscle power; skilled masons and bricklayers, carpenters, scaffolders and riggers, perhaps; metalworkers, who gilded many of the domes; and finally, the most skilled artisans of all, those who carved the statues and the exquisite and complicated bas-reliefs in the corridors of Angkor Wat and the Bayon.

When the blocks were on site, the construction workers would take over and the exhausted transport crews would perhaps be allowed to rest a while before returning to Phnom Kulen for more stone. The blocks were dressed on site and a close fit was achieved by grinding the blocks against each other; joints are rarely at right angles and there are rarely perfectly flat planes. After this, the blocks would be rolled to the base of the worksite, ready to be lifted into position to where the masons toiled high above on wooden or bamboo scaffolding probably very similar to that which is still widely used in Asia today, as is shown on the Bayon friezes.

The builders probably used a variety of lifting gear to assist in their work. There is some evidence of the use of metal lifting dogs and clamps and it is highly likely that blocks were also lifted on rope slings, which were attached to wooden pegs inserted into holes drilled in the stone. Afterwards, the pegs were removed and the holes filled with mortar, as we can see on many of the monuments today. We also know from the Bayon bas-reliefs that Khmer sailors used windlasses and pulleys, so it is probable that similar lifting gear was used at Angkor, logically in conjunction with gin poles, sheerlegs, gallows frames, whip hoists and rudimentary cranes. Perhaps other stones were winched up temporary inclines of compacted earth. One can imagine the scene high above the ground atop the scaffolding—workers spreading mortar compounded of powdered limestone, vegetable juice and palm sugar, in the shadow of a huge block of stone swinging above, the labourers inching it down into position, their muscles aching from the effort. Construction work is dangerous even today with vastly superior technology, so the death toll must have been colossal with such enormous pieces of stone, dizzying heights and rattan ropes. We will never know how many workers plunged to their doom or were crushed to death by falling masonry.

One of the most curious facts about Khmer building techniques is that they never discovered the secret of the true arch, which employs a keystone to prevent it from falling down. Instead, the Khmer builders used the more rudimentary method of corbelling—gradually bringing in two facing edges of wall until they touch—giving an almost gothic appearance to the edifices. This technique can only be used with massive stone or brick walls, not for lighter domestic architecture. It can be seen on many of the ancient temples, and even on those Angkorean bridges that are still in use today. Another curiosity is that the columns of the temples are almost always square or rectangular in cross-section, probably because the Khmers were afraid that the natural round shape of trees was the abode of spirits. Where columns are round in section, this is because the Khmers wished to bring spirits into the building.

What kind of civilisation built the monuments?

Today, natural decay and the ravages of vandals and thieves (including the French novelist André Malraux, it might be said) have left their mark, but no one who visits Angkor can fail to be stirred by its grandeur. Yet, although the spectacular stone and brick ruins the kings left behind are the most visible reminders of Angkor’s past glories, they tell us only part of the story and this chapter does not purport to be a guide to the ancient remains. What is perhaps even more intriguing is the question of what kind of civilisation was able to devote so much labour and so many resources to such gigantic projects. We actually know a surprising amount about the lives of the common people of Angkor. It is now clear that the temple complex was the centre of an enormous dispersed city, home to up to one million inhabitants, making it the largest city of antiquity. The empire itself comprised some 90 provinces at the time of Zhou Daguan’s visit.

Zhou Daguan, who visited Angkor the year after Jayavarman VIII’s death in 1295, has left us fascinating details of what the city was like during its period of human occupation, and although the decline had already set in by then, Angkor was still an impressive place. Zhou tells of a ‘walled city’ with five gates and lines of statues ‘brilliant with gold’. Many of the buildings were gilded; Zhou describes a ‘square tower of gold’ (Neak Pean) at the centre of a lake, the ‘Golden Tower’ of the Bayon, and another of bronze. North of the Golden Tower was the royal palace, an opulent wooden structure with long colonnades and floors of yellow pottery and lead tiles. The immense lintels and columns of the palace were richly carved and there was a frieze of elephants in the chamber of state, lit by a golden window. In this setting, the king (Srindravarman at that time) moved around in sumptuous garments bedecked with pearls and precious stones. Although he had five official wives, he also kept a huge harem, with ‘three to five thousand’ concubines and ‘palace girls’ who seldom set foot outside the palace. The parents of noble families thought it an honour for their daughters to be accepted. Anyone wishing an audience with the king had to abase themselves, crawling across the floor, forbidden to actually look at this exalted personage or, more strictly, god-king.

The king never left the palace except as part of a grand procession of soldiers, palace girls, royal ministers and princes, many of them in palanquins and chariots or astride elephants with ‘flags, banners and music’ and hundreds of golden parasols held aloft. The king himself stood ‘erect on an elephant and holding in his hand the sacred sword’. The royal elephant’s tusks were ‘sheathed in gold’ and around the royal beast were the massed ranks of the king’s bodyguard. Any passers-by who caught sight of the king ‘were expected to kneel and touch the earth with their brows’. Marshals seized anyone who failed to comply, and placed him or her under arrest.

The Angkorean social system

In total, 28 kings ruled over this vast and powerful empire for over 600 years. Although in theory kingship was hereditary and monarchs were devarajas, or god-kings, in practice usurpers were common enough, the qualification being that they had to prove they were blood descendents of Jayavarman II, the founder of Angkor. It was for this reason that dignitaries and military leaders were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the reigning king, on pain of horrible punishments. One such oath is recorded in an inscription translated by Coedès, and promises eternal punishment in hell if it is broken. As the writers Mabbett and Chandler remarked, although Angkorean society was hierarchical, the fact of usurpation indicates that the rulers were not ‘worshipped as gods and given unquestioning obedience by all their subjects’. The extraordinary security measures described by Zhou Daguan above attest to this.

Nevertheless, although they feared usurpation, these kings were absolute rulers in every sense of the term. As devarajas, their power surpassed even that of the European monarchs who claimed to rule by divine right. The inscriptions indicate that they were seen as incapable of breaking religious laws, and they were the source of all legal power in the empire. The law itself was administered via a hierarchy of courts and legal officials. The lower courts dealt with routine matters, but the royal court itself could deal with even the pettiest of matters. Zhou Daguan records that every day the king held two audiences, for which no agenda was provided and which could be attended by both ‘functionaries and ordinary people’ for the adjudication of disputes. The inscriptions show that commoners could bring lawsuits against one another and a common method of ascertaining who was in the wrong was to place the plaintiff and the accused in stone towers for a period of three to four days. It was held that the person in the wrong would always develop an illness, such as catarrh, fever or ulcers. The penalties for convicted malefactors were often draconian. For the gravest crimes the punishment was death, possibly by decapitation with a sharp sword, as in the 19th century, but it was possible for felons to be buried alive.

Five of the worst crimes are mentioned in the inscriptions: murder of a priest, theft, drunkenness, and adultery, or complicity in any of these. (The tradition persisted: during the reign of King Norodom under the French Protectorate, a young Vietnamese servant girl was put to death for knowledge of the adultery of her mistress, a wife in the king’s harem.) It is also very likely that the Cambodian kings sponsored human sacrifice and that the custom predated Angkor and persisted into the 19th century. A Chinese account of a visit in 616 AD claims that the victims were dispatched during the night at a ceremony attended by the king at a hilltop temple called ‘Ling-kia-po-pho’. David Chandler believes that human sacrifice in post-Angkorean Cambodia was reserved for those found guilty of serious crimes. The unfortunates were decapitated as part of the loen nak ta ceremony during rice planting as an offering to the consort of Siva.

The inscriptions also record a range of cruel punishments for lesser crimes, including punches to the face, flogging, amputation of the hands and lips, and squeezing of the feet or head in a vice. An inscription from the 11th century records that one wretch had both his hands and feet amputated. The methods of ascertaining guilt were no less cruel and included, as in China and Europe, trial by ordeal. Zhou relates that the accused might have his hand thrust into boiling water and would be deemed innocent if the skin did not flake into ribbons.

Angkor, in common with most state societies throughout recorded history, was never a democracy and although social stratification in Cambodia has never been as rigid as the caste system of India, there was little social mobility. The ruling elites owed their position to birthright and the lower orders by and large accepted their status as natural, particularly as it was closely bound up with the religious idea of one’s station in this life being a reward or punishment for deeds in past lives. Liberty was an alien condition beyond the social imagination, without words to express it, although some ‘plebeian’ revolts do appear to have broken out before being brutally suppressed. The doctrine of reincarnation at least held out the promise of better luck next time, if one had lived an honest, obedient and virtuous life. As we shall see, life for the common people and slaves was onerous indeed and legends such as the Churning of the Sea of Milk gave hope to the downtrodden. This legend, depicted on the bas-reliefs of Angkor Wat, shows lines of people pulling a rope backwards and forwards, looped around a pole which is resting on the back of Kurma the tortoise. The aim of the exercise was to recover lost objects from the sea, foremost of which was ambrosia, the gift of immortality. Ambrosia also meant prosperous times, ample food, and well-deserved rest after the rigours of labour in the fields or construction sites.

The strict stratification of Khmer society was reflected in the division of the common people themselves into different categories; the knum who were bound to the monasteries, temples and religious orders; the peasants or the soldier-builder-farmer class; and slaves. The Angkorean civilisation supported a number of large religious foundations and monasteries, which had great influence in Khmer society and whose activities are recorded in some detail in the inscriptions. These orders controlled vast tracts of land and employed large numbers of workers. There is surprisingly little in the inscriptions about the monks and abbots of these orders, but a great deal about those who did the work, the knum, who appear to have been bound to the land in a condition akin to serfdom or perhaps slavery, although perhaps this condition was mitigated by the belief that they carried out the ‘work of the gods’. Some of the knum appear to have been slaves in the strict sense of the word; they could be bought and sold and were often prisoners of war or captured hill tribesmen from beyond the settled lands. Others seem to have been villagers from the vicinity of the monasteries and foundations. The inscriptions are explicit on the division of labour, with field hands, herdsmen who looked after the herds of sacred cows, fruit pickers, guards and other outdoor workers. There were also weavers and clothing workers, secretaries, kitchen hands and cooks, even parfumiers and ‘guards of the holy perfume’. Still others were employed as singers, dancers and musicians within the temples.

The most numerous class were the peasants, who also served as labourers on the temple construction sites, and who were liable to be mobilised into the army in time of war. These appear to have been a different category to the knum, for they were able to keep slaves themselves; Zhou Daguan records that only the very poorest peasants did not keep at least one slave. In many respects, the lives of this peasant class appear to have been similar to those of the modern Khmer peasants, who were until recently liable to serve as corvée labourers on the roads and other public works, or work free of charge for the benefit of rural notables. The men dressed in loincloths, the women wore a longer garment much like the sampot of today and both went naked to the waist. These garments were of simple design for, as Zhou tells us, the poor were forbidden to mimic the sumptuous garments of their ‘betters’, even if they could have afforded to do so.

Clothing reflected rank in this rigidly stratified society and only the king was allowed to wear clothing with an overall design. Whereas the common folk dressed in material of coarse fustian weave, the nobles were clad in silk, which most likely came from abroad (as did wool). Rank was also reflected in physical complexion, particularly for women. The women of the upper class prided themselves, as they do today, in their light complexions. They did not work outdoors and took parasols when they ventured outside. The skin of the women of the poorer classes was burned dark by the sun.

The soldier-builder-farmer class also included those who made their living by petty trade. The Bayon bas-reliefs depict market scenes, in which many of the traders were women, selling farm produce and other goods—or rather bartering them, for the Khmers had no currency. In addition, there were better-off Chinese merchants and a long history of Chinese settlement and intermarriage in Cambodia. Zhou records that Khmer wives were keenly sought after by Chinese settlers, who valued their business acumen.

Perhaps different from the knum were the slaves-proper, who must have been very numerous in Angkor. We do not know what proportion of the population were slaves, but if the evidence supplied by European observers in the 19th century is anything to go by their numbers must have been considerable—perhaps hundreds of thousands across the empire. The evidence from inscriptions, such as that at Preah Khan, suggests that slaves included debtors, hill tribesmen and prisoners of war. Slavery was hereditary, although they could in exceptional circumstances be emancipated by the king.

We do not know how much of the work was carried out by slaves, but it is likely that the Angkorean economy and public works schemes relied upon them to a large degree, although according to inscriptions they did not form the majority of the labour force. Most likely, they were put to the hardest physical labour, including tasks such as canal building and maintenance, and quarrying and transporting the enormous blocks of stone for the construction of the temples. However, other slaves did higher or less onerous grades of work, employed for example as clerks or scribes, domestic servants and musicians. Some were known by titles such as ku—or ‘born for loving’—suggesting compulsory employment as prostitutes. Probably the worst treatment was meted out to hill tribespeople who, even up until the abolition of slavery by the French in the 19th century, were viewed with contempt. This is reflected in their names, one of which was recorded as ‘Stinking’.

The price of slaves varied depending on individual age, strength and skill. Inscriptions from religious orders indicate that female slaves might be bought for twenty measures of unhusked rice. Another inscription records that a particular slave was exchanged for a metal spittoon. Yet another slave was bartered for a buffalo which itself was valued at five ounces of silver. Runaways were savagely punished; the milder retributions included slicing off the ears.

The religion of Angkor

Life for all except the Brahmans and the aristocracy must have been hard in Angkor, yet suffering was mitigated by the consolations of religion. Angkor, like modern Cambodia, was an intensely religious society, with all aspects of life inextricably bound up with faith. The religion of Angkor, as with Funan and the other Khmer principalities earlier, was imported from India, but was modified by local tradition. There was a caste of hereditary priests (a remnant of the broader Indian caste system, perhaps) who purported to trace their ancestry back to those who had served Jayavarman II. For most of the 600 years of Angkor, Hinduism cohabited fairly comfortably with Mahayana (Greater Vehicle) Buddhism, albeit mixed with Khmer folk beliefs and superstitions. At times the pattern was broken by periods of religious iconoclasm, during which partisans of the different sides damaged religious statues in sectarian frenzies much as the early Christians defaced the works of pagans in the Roman Empire. A number of Buddhist statues in the Bayon, for instance, were damaged—perhaps by Brahmans, as statues of Siva and Vishnu were not damaged.

The Cambodian variety of Hinduism differed in some ways from that in India. In India, Brahma was the chief god of the Hindu trinity; in Cambodia, Siva and Vishnu shared first place. During the 13th century, however, a new religion, or perhaps a variant of an older one, appeared. This was Theravada Buddhism, or the Lesser Vehicle. Although it shared many of the beliefs of the older Buddhist sect, Theravada Buddhism taught that one would arrive at nirvana via a saintly and ascetic life, during which one should be resigned to suffering. Quite simply, good karma was determined by doing good works. The Greater Vehicle held, in contrast, that one could achieve nirvana via appeals to incarnations of Buddha, or bodhisattvas. The two older religions had also merged with the devaraja cult, whereas Theravadism tended to undermine it. Some writers, George Coedès notable among them, have pointed to the possible role of this gentle religion in the decline

Apsara, celestial nymphs and dancers, were represented at the beautiful Banteay Srei.

(Author’s collection)

of the empire. Yet it brought solace for the common people, on whom the demands of their rulers for labour on the temple construction sites had become an intolerable burden.

The idea of reincarnation was prominent in all of these religions, yet the very wicked and disobedient could suffer eternal damnation. The hell scenes on the Angkor Wat friezes show that blasphemers and those who destroyed religious artefacts, along with those who bore false witness and gluttons, adulterers, arsonists, liars, poisoners and thieves could expect to go to hell. Interestingly, given that hell in the western tradition is a place of perpetual fire, the Khmer version is one of eternal, bone-chilling cold. One frieze shows another Khmer vision of hell, with sinners climbing thorn trees as punishment for their wicked ways. Life and religion were inseparable; indeed, life without religion would have been unthinkable. And although the Khmer religion, particularly in its Theravada form, is in line with Marx’s characterisation of religion as ‘the sigh of an oppressed creature in a heartless world’, the Hindu and Mahayana priests were an integral part of the ruling class and the caste system.

Everyday life in Angkor

Zhou has left an account of the houses of the common people, which were remarkably similar to those of the peasants today; built of wood or bamboo and standing on stilts, and thatched with woven sugar palm fronds, for they dared not imitate their social superiors who were allowed to put tiles on their roofs and live in larger dwellings of more intricate design, built of more durable woods such as koki. (Pieces of this tropical hardwood, richly decorated, have survived at Angkor Wat.) The interiors of the houses of the poor were much as found today in rural Cambodia: simple places, spread with palm mats and without tables or chairs. The common people had few possessions apart from some ceramic pots and other basic kitchen utensils.

Although they do not seem to have been a particularly sybaritic people, sexual morality was somewhat more liberal than in many other societies. Khmer mores allowed a wife or husband to have another sexual partner if a partner was absent for more than ten nights, although this could be dangerous as a husband could have a man who cuckolded him put in the stocks. Khmers married in their teenage years and once a couple were betrothed, premarital intercourse was accepted. A major rite of passage for girls was the custom Zhou Daguan has recorded as the chen-t’en, which tends to shock modern readers. Following lavish celebrations, a priest would deflower the girl with his hand, for which he would be rewarded with gifts of alcohol, rice, cloth, silver, betel and silk. In wealthier families, the ceremony happened when the girl was aged between seven and nine years old, in poorer, when she was 11. Some slave women appear to have been made to work as prostitutes, and male prostitution and homosexuality existed.

Although some Khmer customs, such as women urinating while standing up, struck Zhou as ‘absurd’, the Khmers for their part were equally shocked or amused by the behaviour of the Chinese, particularly by the latters’ habit of cleaning themselves with paper instead of water after defecation. The Chinese custom of using human manure to fertilise the fields also shocked the Khmers, who abhorred it as bodily pollution, a belief probably inherited from India. These attitudes have continued to the present. More puzzling is the matter of how the ancient Khmers disposed of their dead. Zhou Daguan claims that corpses were either left outside the city for wild animals to dispose of, or were buried or cremated. (Earlier, in Funan, cadavers were cast into the rivers.) Zhou’s belief that cremation of the dead was a new practice when he visited in the 13th century is contradicted by another Chinese account, which records that the custom was already established in the early seventh century. Although the Khmers believed in reincarnation, death was nevertheless an occasion for grief, and the mourners would shave their heads as a mark of respect and loss.

The staples of their diet were rice and fish, which was plentiful in the artificial and natural watercourses of Angkor, and which was cooked fresh or added to other dishes in the form of the pungent fermented paste, prahoc, as it is today. These staples were supplemented with fruit, particularly oranges and bananas, of which there were numerous kinds, but also tamarind, edible flowers (from the dipterocarp hardwoods, for example), coconut milk and flesh, mangoes and mulberries. A number of varieties of beans, along with sorghum millet and sesame, were also cultivated. Fermented alcoholic beverages were made from sugar cane and perhaps rice and honey. We know from the inscriptions that the Khmers ate venison and pork, but these meats were perhaps beyond the reach of the poorer members of society. They drank milk, but this, along with meat, was largely proscribed when Theravada Buddhism arrived. Although the fiery chillies with which Southeast Asians love to flavour their food were imported into the region by the Portuguese after the demise of Angkor, the ancient Khmers spiced up their food with a variety of condiments including cardamom, turmeric and black pepper (all of which are still grown in Cambodia today) and salt, which was brought by boat from the Kampot district adjacent to the Gulf of Siam.

There is a wealth of detail about the customs and amusements in Angkor. From these we know that the Khmers had a variety of musical instruments, including percussion (drums, cymbals, tambourines and bells) and stringed instruments resembling harps and guitars, or perhaps mandolins. Rockets and firecrackers were set off during major festivals, as Zhou observed. The bas-reliefs also depict: elephant, pig and cock fights; snake charmers, raconteurs and strolling minstrels; pugilistic games and archery contests; and team games, one of which resembled polo and which is depicted at the Terrace of the Elephants at Angkor Thom.

The hydraulic city debate

It is something of an understatement to say that water was important to the ancient Khmers. Angkor is situated in a region that is subjected to six months of drought and six months of rain every year, unlike the delta, where Funan was, which has high, year-round rainfall and a surfeit of river water. The early archaeologists quickly became aware that the ancient Khmers had built three enormous barays, or artificial lakes, the largest of which, the West Baray, measures some 8 kilometres by 3 kilometres. More recently, satellite imagery has revealed that there was a fourth baray, long since drained. The West Baray, started between c.975 and 1020 and completed in 1050, was formed by throwing up 10-metre high earthen ramparts, which extended for over 20 kilometres: a project that took colossal amounts of man-hours and human sweat to build. The first baray, the Indratataka, had been built earlier, in 877 AD, during the reign of Indravarman. Yasovarman I, who succeeded him to the throne, built a new reservoir, the Yasodharatataka, in 889 AD.

In 1961, the archaeologist Jacques Dumarçay found a length of copper pipe on the artificial island in the centre of the lake and this, together with other evidence, led him to surmise that the king would regularly visit and use the pipe to measure water levels to ascertain whether rice planting could begin. Dumarçay, like others before him, assumed that the purpose of the barays was at least partly to do with irrigation. This idea found its fullest expression in the work of the celebrated French archaeologist Bernard-Philippe Groslier, who developed his controversial ‘hydraulic city’ hypothesis in two articles published in 1974 and 1979. According to Groslier, a vast irrigation system of canals, tanks and larger reservoirs, of which the barays were part, had allowed the Khmers to plant two, and even three rice crops per year instead of one (Zhou Daguan claimed three or four crops annually). This highly efficient agricultural system had enabled the Khmers to provide for a huge city population of perhaps close to two million. The social surplus product also enabled the leisure time needed for the creation of sophisticated high culture, including the ‘plastic arts’ and literature. It also provided stockpiles of food to feed the enormous numbers of labourers and artisans necessary for the construction of the monumental temples of Angkor.

Although it is likely that Groslier’s original population estimate was too high, Angkor was probably the largest pre-industrial city in the world. The most recent archaeological work indicates that one million is a reasonable estimate of the city’s size. Groslier’s hypothesis was important because it represented a shift in focus away from the monuments themselves to an investigation of the society that had produced them. This does not mean that scholars such as George Coedès had ignored the social dimensions of Angkor, but the emphasis did begin to swing to a more anthropological approach.

The hydraulic city debate soon came under fierce attack and the debate still rages, often with more heat than light. In 1980 and 1982, the distinguished writer W.J. van Lière published two articles in which he wrote that ‘not a drop of water from . . . the temple ponds was used for agriculture’. Van Lière claimed that there was no evidence of the existence of a network of irrigation canals, or of intake or outfall structures at the barays. The ancient Khmer rice crop, he insisted, had depended on bunded fields and flood retreat agriculture, much as today. (The former refers to the practice of erecting low dikes around paddy fields to trap rainwater, the latter to a system of embankments to trap retreating floodwaters to irrigate crops.)

More recently, the American geographer Robert Acker has disputed Groslier’s estimates of the size of Angkor’s population, at the same time accepting van Lière’s claims that there is no evidence to suggest the existence of irrigation works. James Goodman argues that the key to understanding the extraordinary productivity of Angkorean riziculture lies in the salient natural feature of the region—the Great Lake. Every year, during the monsoon and after the spring thaw in distant Yunnan, the volume of water in the Mekong is so great that it cannot drain away quickly enough through the delta to the sea. Immense quantities of water build up on the flat lands at Phnom Penh and, with nowhere else to go, flood upstream into the Tonlé Sap River, reversing the normal direction of flow and pouring into the Great Lake. As a result, the level of the lake rises by between 7 and 9 metres and floods an area of over 13 000 square kilometres. This, argues Goodman, made food production ‘virtually climate proof’. Goodman also argues that the main settlement pattern of the Angkorean civilisation followed the flood line on the fertile lacustrine plain, with dense settlements between Angkor and Banteay Chhmar, rather than in the immediate environs of the temple complex adjacent to the modern town of Siem Reap. Goodman also points out that the soil in the vicinity of the monuments is poor and that it would have required heavy manuring to maintain any fertility. Although human manure has been used as fertiliser for many centuries in Vietnam and China, the practice, as noted previously, is abhorrent to the Khmers. Goodman asks why, if irrigation were the preferred method in ancient Angkor, it accounts for less than one per cent of rice produced in the Siem Reap region today. Finally, in the view of these critics of Groslier’s original thesis, the barays and smaller artificial lakes had a purely religious purpose.

It is unfortunate that the debate has become so polarised, with supporters of the hydraulic city thesis dismissed as dogmatic Wittfogelians (see Glossary). Groslier never doubted that the barays and canals had a ‘dual function’, both for utilitarian and religious purposes, and argued that the Khmers would have made no distinction between the two. The Japanese scholar Yoshiaki Ishizawa maintains that ‘in reality, it is impossible to separate the everyday lives of the Cambodian people from ponds and water’. The utilitarian purposes of the waterways (for example bathing, fishing, irrigation, flood control and drainage) were inseparable from the Khmers’ religious faith. Many ponds are associated with temples and often the barays and smaller lakes have a religious shrine in the centre. It is very likely that the moats were originally dug to provide landfill for the temple mounds and that they served thereafter for drainage purposes. It is also clear from the inscriptions that the waterways served for purposes of religious purification and that the temple mounds and moats and barays were a symbolic representation of Khmer cosmology. The temple represents Mount Meru, at the centre of the world; the city walls represent the sacred Himalayas; the moats and barays represent the oceans and seas. The Siem Reap River, too, was the Khmer version of the sacred Ganges. So too were the drops of water with which the Khmers bathed their bodies or watered their crops seen as part of the sacred order of the world.

W.J. van Lière’s assertion that not a drop of water from the barays and canals was used for irrigation has been repeated by Groslier’s opponents without them checking the known facts. The evidence— much of it new—suggests strongly that the waterways did have a dual function. Many inscriptions refer directly to the waterways and although the majority of these do refer to their religious functions, some explicitly mention irrigation. One inscription in particular refers to canhvar, which means a waterway used for irrigation purposes. It should also be remembered that a number of Iberian travellers who visited Cambodia during the 16th century, when Angkor was still inhabited, remarked that the prosperity of the kingdom relied on irrigation.

This does not mean that the Khmers did not employ other methods for growing crops. It is altogether likely that they practised dry rice farming in remote areas and that they built dikes around other paddy fields to capture rainwater in other areas distant from the canals. They probably also carried out flood retreat farming in the fertile areas subject to inundation along the Great Lake. Indeed, if the estimates of the population of the ancient city are correct and over one million people lived there, it is altogether likely that they had to employ multiple methods of farming. However, the latest archaeological evidence indicates that a vast system of irrigation canals and reservoirs was at the centre of the Angkorean economy. W.J. van Lière claimed that as he had not seen any intake or outlet structures at the barays, or any distribution systems, these did not exist. The latest evidence from aerial photography and radar imaging indicates that Groslier’s critics were quite wrong to assert that there were no canals at Angkor.

The Australian archaeologist Roland Fletcher insists that Angkor was a ‘gigantic, low density, dispersed urban complex’ sprawling over at least 1000 square kilometres between the Great Lake and the Kulen Hills to the north, and that the irrigation system was vital to the city’s survival. Some of the larger canals still exist, for instance at Beng Melea, east of Angkor, where they took water from the temple moat to the rice fields. Remote sensing also shows the existence of a network of distributor channels, and larger canals of up to 40 metres in width are visible from the air with the naked eye, leading from the East and West barays and the Angkor Wat moat. Although W.J. van Lière categorically ruled out the possibility of the ancient Khmers creating temporary breaches in the baray embankments to drain off water for irrigation purposes during the dry season, this still remains a distinct possibility. In 1935, M. Trouvé of the Hydraulic Service of Indochina conducted an experiment at the West Baray. A breach was made in the embankment, a pipe inserted and the earth replaced around it. Shortly afterwards the dike broke, but was repaired more carefully and remained intact thereafter. It is possible that the ancient Khmers inserted laterite pipes through the embankments and remote sensing shows possible breaches. It is also now known that the barays had permanent outlet/inlets in their eastern walls.

Even more importantly, the latest evidence shows the existence of a large feeder canal, perhaps 20 metres in width, which ran northwards for some 40 kilometres from Angkor Thom to the hills. This trunk canal fed a fine network of distributors and embankments, which covered a large area to the north of the central city. This area, which naturally was rather dry for six months of the year, was converted by the Khmers into what Roland Fletcher describes as ‘a highly structured anthropogenic wetland’, criss-crossed with canals and embankmentcum-roads and capable of supporting the largest concentration of people in the pre-industrial world. These people lived in a dispersed pattern, strung out along the canals and embankments, ringing the paddy fields, or clustered around the numerous smaller reservoirs. The slope of the land is gentle, so erosion would not have been a major problem except in the foothills of Phnom Kulen.

Fletcher also suggests that the barays could have functioned as ‘complementary opposites’—both as reservoirs and as settling ponds for silt brought through the canal system to the north from the hills. It is probable that the city was able to function in a state of ‘dynamic equilibrium’ for many centuries before increased population pressure caused the people to seek additional land to settle on and cultivate. It was then, argues Fletcher, that the fine ecological balance of the city began to break down and the city and its empire went into decline.

The decline of Angkor

That empires rise and fall is a cliché of history and Victorian melodrama. What are more difficult to establish are the specific reasons for their decline. The puzzle of the Angkorean decline has taken a long time to unravel and we still don’t have all the answers. It is likely that the city’s decline resulted from a combination of political, social, religious and ecological factors. The conventional explanation held that collapse came suddenly, around 1431, when the Siamese King Paramaraja II sacked the city. Christopher Pym believed that the cause was ‘the empire’s dismemberment from without and a loss of religious equilibrium within’. The Siamese (or Thais), who had moved into the Menam basin from Yunnan, were originally under Khmer suzerainty, but after the death of Jayavarman VII they established their own sovereignty and began to challenge Khmer hegemony. Zhou Daguan records that there were devastating wars between the Siamese and the Khmers in the mid-13th century, with great loss of life and destruction of property in the outlying areas of the empire. Even before they sacked Angkor in 1431, the Siamese had occupied large parts of the empire, carrying off Khmers as slaves and possibly sabotaging the irrigation system according to some writers.

While the incessant Siamese incursions undoubtedly weakened Angkor politically, it is unlikely that they caused the empire’s collapse. Although the Khmers shifted their capital to the Quatre Bras region after the Thais sacked Angkor in 1431, the city was not completely abandoned. When the Iberian missionaries Diego do Couto and Gabriel Quiroga de San Antonio visited the city in 1550 and 1570 respectively, it was still a going concern, the latter noting that the kingdom was still densely populated. (Do Couto’s account of Angkor was lost for centuries until re-discovered by the celebrated English historian C.R. Boxer in Lisbon in 1954.) King Satha I carried out extensive rebuilding work on the temples and the irrigation system during the same period and an inscription from 1587 records restoration work on Angkor Wat. Angkor Thom seems only to have been abandoned in 1629, but other parts of the city were refurbished during the reign of King Ponhea Sor in 1747. Tragically, a description of the city written by a European traveller in the 1780s has been lost. When the French came in the 19th century, there were still Buddhist monks at Angkor. The city, however, was in ruins, with much of it lost to the rapacious advance of the jungle. Something had happened, but at a later date than the Siamese attacks, which suggests that although these might well have weakened the empire, they are not the sole explanation for its decline.

George Coedès believed that the mania for temple building placed an immense burden on the people, and was a huge drain on the resources of the empire. (If the excesses of Louis XIV, the Sun King, absorbed no less than 50 per cent of the wealth of 17th-century France, one wonders at the exorbitant cost of the much larger building programs and other demands of the Angkorean kings.) The excessive demands wore the people down, drained their vitality and perhaps even led to rebellions, although there is no real, hard evidence of this, just tantalising hints in inscriptions. After the frenzy of temple building during the reign of King Jayavarman VIII in the 13th century, during which monuments were thrown up at feverish speed, the program ran out of steam. British historian Arnold Toynbee might be guilty of hyperbole when he writes, ‘The Khmer civilization, like so many civilizations before and after it, wrecked itself by indulging in these mad crimes’, but there is an element of truth here. This great coda of temple building also coincided with the arrival of the new religion, Theravada Buddhism, via a Burmese monk called Shin Tamalinda, whose standing was no doubt enhanced by his claim to be the son of a Khmer king.

The common people took to the new religious doctrines with great enthusiasm. By the mid-14th century the country had converted to the new creed and Sivaism and Mahayana Buddhism were displaced. (Elements of Hinduism persist to this day in Cambodia, however, and include aspects of royal court ritual, art and literature, and the recognition of Indian gods.) Khmers even travelled to Laos to proselytise for Theravadism. The new religion was ‘democratic’ in that there were no hereditary priests, such as the Brahmans—anyone might don the saffron robes and become a monk, and even a king who converted might beg for alms in the street. The new religion made a huge impact on those exhausted by the worldly demands of their sybaritic rulers. The material world was one full of vanity and one’s best chance of a better reincarnation and eventual ascendance to nirvana lay not with the accumulation of power and wealth, but in renouncing it and dedicating one’s life to good works. And what were the temples but monuments to the monstrous vanity of men who presumed to be gods when, according to the Theravadins, not even Buddha himself was a god?

One can only speculate what effects the new religion might have had on the economy. Pym says that because of Theravada Buddhism’s spurning of the material world, the irrigation system fell into disrepair. Again, there might be an element of truth in this. Although the modern Khmer peasants are often scorned as being lazy, particularly in comparison with their industrious Vietnamese neighbours and by the yardstick of the European Protestant ethic, this really is a misunderstanding. For the Khmer peasants, like their Irish counterparts, ‘contentment is wealth’. The purpose of life is not the accumulation of material goods, but to live a good life, which includes the renunciation of earthly desires in order to accrue merit. As the historians Chandler and Mabbett have observed, the ‘indolence’ of the Cambodian peasants is ‘a form of wisdom’. It is quite possible that the new religion did, as Coedès argues, sap at the foundations of a society that was predicated on the existence of strong, centralised state power. Marx’s theory of the Asiatic Mode of Production (AMP) has fallen somewhat into disrepute, not the least because it is often confounded with Karl Wittfogel’s dogmatic generalisations about ‘oriental despotism’. However, while the theory of AMP does not fit with many of the diverse societies of Asia, it does measure up remarkably well to Angkorean civilisation, a hierarchical society based on a strong state, without landed property and with a heavy emphasis on government public works schemes. If Groslier’s hydraulic city thesis is established it is very possible that Theravada Buddhism might have acted as a subtle yet powerful agent subversive of Angkorean state power. This might also help explain why irrigation is not widely used in modern Cambodia.

The new religion also forbade the taking of life, and although this has not prevented subsequent generations of Cambodians from warlike behaviour, it might have dampened the imperial ambitions of the kings. It is not unknown for Khmer peasants to spurn other Khmers who have taken human life. Anthropologist May Ebihara has recorded that some villagers disdained those who had taken human life during the Khmer Issarak insurrection of the 1940s and 1950s against France.

The legend of the kingfishers

The eccentric English writer Osbert Sitwell recorded a charming Khmer tale which held that Angkor fell into decline because the supply of kingfisher feathers, which were exported to China, ran out. On one level the tale is absurd, yet read as a parable it perhaps contains the key to the decline of a great empire. Bernard-Philippe Groslier drew attention to the possibility of ecological damage as a factor in the decline of Angkor, and the thesis has been fleshed out by the more recent work of Roland Fletcher. Groslier believed that there was probably extensive environmental damage in Angkor, with deforestation of the slopes north of the city leading to leaching, soil compaction, sheet and gully erosion and the silting of watercourses on the flatter lands. It is likely too that deforestation caused a decline in the amount of water available from convectional rainfall. The conventional wisdom that silt is immediately fertile is in fact untrue. Soil is a complex biosystem and to become fertile it needs the addition of humus from plant material along with the actions of worms, insects and microscopic organisms. While the barays might well have functioned as a dialectical balance between storing water and as sediment traps, deforestation of the watersheds could have drowned the canals in silt faster than it could be cleared. It is also possible that rotting waterweeds depleted the amount of oxygen in the canals and moats, a process known as eutrophication. This most certainly is a problem in modern Cambodia, with a plentiful supply of water-borne nutrients providing ideal conditions for the rapid growth of plants such as hyacinth and lotus. Rapid growth and decay seriously depletes the amount of oxygen in the water and reduces its value for irrigation and smothers fish life.

Groslier also speculates that the large quantities of slow-moving water would have provided a breeding ground for malarial mosquitoes. In fact, there is evidence that irrigation systems in British India did increase malarial infection rates, and it is well known that Mussolini’s actions in draining the Pontine marshes near Rome led to a decrease in infection rates. Within a decade of the opening of the Sarda Canal in India in 1928, the irrigated areas suffered problems of evaporation and seepage, but also ‘waterlogging, salinity and malaria’. Earlier British attempts to use the waters of the Cauvery and Coloroon for irrigation purposes largely failed because of silting. Salting might have been a problem in Angkor too: many Cambodian soils have problems with salt and sodicity; for instance, 50 per cent of the soils of modern Kompong Speu province are sodic at a depth of 30 centimetres.

In the language of systems-theory, the Angkorean irrigation system was a delicate balance of human and natural inputs and outputs—a dynamic equilibrium—which was capable of sustaining a population that was huge by the standards of antiquity. The system was thrown out of ecological balance by the cutting of large areas of forest, particularly on the watersheds in the Kulen Hills. Roland Fletcher believes that the trees were cut down to provide more farmland for an expanding population and that there was ‘a vast consumption of timber . . . for the scaffolding of the temples [and] for building the palaces and houses . . .’. Timber would also have been used for cooking and ‘industrial’ purposes, both in the peasants’ houses and on the monastic estates. Put in this context, the legend of the kingfishers is not so far-fetched after all. Damage to the ecosystem of Angkor might well have first manifested itself in the disappearance of the birds. With no scientific explanation for this, the Khmers might well have regarded the disappearance of the birds as a harbinger of doom.

If Fletcher is right, the fate of Angkor is a lesson for modern Cambodia and the rest of the world. There is mounting evidence that Cambodia is suffering an accelerating environmental crisis that could mimic the calamities of the ancient Khmers. Logging—much of it illegal—is widespread on the hills and ridges. As a consequence, sheet and ravine erosion is increasing, with silting of land and watercourses downstream. The results of such recklessness are compounded with the effects of the current Chinese dam-building program in Yunnan, which has led to record low water levels in Mekong and the Great Lake in Cambodia. The loss of habitat, which has seen a marked decline in the numbers of wild animals including tigers and crocodiles, might well be a re-run of the habitat loss that ended the trade in kingfisher feathers with China and heralded the decline of Angkor. As Jean Lacoursière, the former head of the Mekong River Commission’s environmental unit, put it: ‘Today we have the technology to repeat, on a larger scale, what happened at Angkor . . . The principles are the same: reduction of habitat, and changes in the overall ecology of Tonlé Sap.’