5

THE FRENCH

PROTECTORATE,

1863–1953

French colonialism arrived in Indochina in 1858, four centuries after the Iberian conquistadors set sail from Manila on a doomed mission to carve out an empire on the Southeast Asian mainland. This time, the Europeans would succeed. French marines landed from warships anchored off Saigon after a pogrom had broken out against Catholic missionaries and their Vietnamese converts. What was ostensibly a ‘protective mission’ became a permanent occupation force. The Vietnamese troops were no match for French marines armed with breech-loading rifles and naval guns. Blocked from expansion in India and kept out of the rest of Southeast Asia by the Dutch, the Spanish and the British, the French were eager to plant the tricolour in Indochina.

Once the French naval officers had established a beachhead at Saigon, they gradually wrested control of the surrounding districts from the Vietnamese authorities. In 1863, they set up a protectorate in neighbouring Cambodia. By 1893, after a bloody war of conquest, they would control all of the Vietnamese territories from the Chinese border in the north to the tip of the Cape of Camau in the south, along with Laos and Cambodia upstream on the Mekong. They partitioned Vietnam into the protectorates of Tonkin and Annam, along with the direct colony of Cochin-China in the south, and gradually tightened control over the protectorates of Laos and Cambodia. The word ‘protectorate’ was a euphemism. After the conquest of Tonkin, French governors-general administered Indochina as a federated colonial unit from Hanoi. Under these republican ‘viceroys’, power was deputised to the Résidents Supérieurs in the four protectorates and the governor at Saigon. The French would stay in Indochina until 1954, when a peace conference in Geneva brokered a settlement to the anti-colonial war that raged in the region after World War II. Cambodia secured its own independence the year earlier following King Sihanouk’s ‘royal crusade’, although this must be seen in the context of France’s reversals in Indochina as a whole, which culminated in catastrophe at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

The tricolour comes to Cambodia

The first administrators at Saigon were naval officers, brisk, efficient and patriotic men who were determined to carve out a place for the Fatherland in the tropical sun. Their behaviour suggests that they had entertained designs on Cambodia some years before the establishment of the protectorate. French missionaries had proselytised in the kingdom since the 17th century, and although they made few converts, they had won the trust of King Duang and several of his predecessors. There had also been a tremendous spurt of popular interest in the kingdom following the posthumous publication of the diaries of the French traveller Henri Mouhot. These contained a description of the ruins of Angkor, which the popular imagination saw as an Eldorado in the East. To acquire them would bring glory to la belle France.

There had been sporadic diplomatic contact with the Cambodian court since 1853, when Ang Duang had sought French protection on the advice of Catholic priests based at Udong. In 1855, the Montigny mission arrived to discuss the request, but Duang, under Siamese duress, declined to pursue the matter. Ang Duang died in 1860 and the following year a French gunboat steamed up the Mekong to the royal capital at Udong, ostensibly to protect Christians from persecution but more likely to ‘case the joint’ as American gangsters might say, with a view to annexation. Around the same time, the Viscount de Castelnau attempted unsuccessfully to reach an understanding with the Siamese about the future of their Cambodian vassal state, and the following year Admiral Bonard made a preliminary survey of the country and its resources. These were tempting prizes in themselves, but the French had two other compelling reasons for their interest. Their old rivals, the British, had an eye on Siam and a friendly Cambodia might act as a buffer against the uncomfortable proximity of ‘perfidious Albion’ (a traditional French appellation for Britain). Secondly, the Mekong was one of the world’s great rivers, running down from distant Yunnan, and the French were interested in its potential as a trading and military artery; what the Australian historian Milton Osborne has called a ‘river road to China’.

The treaty of 1863

When King Duang died in 1860, Cambodian fell into a familiar pattern of instability. Duang’s three older sons, Ang Vodey, Sisowath and Si Votha, jockeyed for the throne, and Cham insurgents marched on the capital. Ang Vodey, the Siamese nominee for the Cambodian throne, no longer had to fear Vietnamese designs on the kingdom, but the Siamese now had a freer hand to meddle and they were jealous lest France supplant them as ‘protector’ of the Khmers. Ang Vodey, who was to reign as King Norodom after his coronation in 1864, sought talks with France on the advice of French missionaries, and this time the response came quickly. On 11 August 1863, Norodom signed a ‘treaty of friendship, commerce and French protection’ with the Breton sailor Admiral Pierre de La Grandière, whose gunboat was moored on the river nearby.

Norodom signed under the muzzles of de La Grandière’s naval cannon, and although the threat was implicit rather than open, the French were determined to bring the country into their orbit. In the circumstances, Norodom probably thought he had made the best of the situation, for the terms of the treaty were apparently innocuous. France was to have the right to station warships and soldiers at the Quatre Bras. The Catholic Church was to receive special privileges and the French could trade freely throughout the kingdom. A French Résident would advise the king. On the other hand, the Cambodians could maintain a representative at Saigon and could trade freely with the French, and the special place of Buddhism as a state religion was ensured. After centuries as a tributary state of Vietnam and Siam, Norodom perhaps figured that he could have made a worse bargain.

Unsurprisingly, King Mongkut of Siam was furious at what he saw as his vassal’s ingratitude. Norodom tried to placate Mongkut by arguing that de La Grandière had bullied him into signing the treaty before he had time to read the Khmer text. In December 1863, Norodom signed a secret treaty with the Siamese king, which ran counter to his pledges to France. His behaviour seems erratic, but perhaps he was uncertain of France’s willingness and ability to defend him against the angry Siamese. The French were busy fighting Vietnamese insurgents at the time and, perhaps more importantly, Emperor Napoleon III had yet to ratify the treaty; indeed there is some evidence to show that the Saigon admirals had acted with considerable autonomy in the matter and in the context of factionalised politics at the imperial court. In fact, Napoleon did not ratify the treaty until April 1864.

It seems that Norodom’s demeanour at the time did not inspire the confidence of the Saigon admirals. Their misgivings intensified when, in March 1864, they caught him trying secretly to slip out of Udong for his coronation at Bangkok. A few salvos from a gunboat convinced Norodom that he should abandon the plan. Instead, he was crowned at Udong the following June in a ceremony presided over jointly by the French and Siamese. The story did not end there, however, for two months later the French learned (via a report in the Singapore newspaper the Straits Times) of his secret treaty with King Mongkut, the terms of which gave the Siamese the right to appoint ‘the kings or viceroys’ of Cambodia and gave further slices of Cambodian territory to Siam. Under French pressure (and on the advice of the British), the Siamese formally agreed that their treaty was null and void.

For the first six or seven years of the protectorate, the colonial hand lay relatively lightly on Norodom, whom the French shored up against a series of rebellions, the most celebrated of which was led by the pretender Pou Kombo. While they were privately dismayed by the misrule of the Khmer administration and by the king’s indifference to the welfare of his subjects, the French naval officers remained aloof so long as they could guide Cambodia’s foreign affairs and their missionary and trading activities were unimpaired. During this period, they were preoccupied with the pacification of the Vietnamese resistance to the piecemeal annexation their country. Besides, France was itself a monarchy at this stage and Napoleon III was no model of probity. This brief pragmatic hiatus ended when the Second Empire collapsed as a result of Napoleon III’s disastrous war against Prussia in 1870. With the new Third Republic came a reforming zeal that coincided with a more vigorous style of imperialism by the European powers. The inefficient and corrupt Khmer state would have to be replaced with government and administration based on European ideas of fiscal prudence, and legal–rational principles. Cambodia, which had been a drain on the French exchequer, would pay its way.

The French reform program

Implementing the mission civilisatrice would prove harder than the French realised. For the next thirty-odd years, the French Résidents would wage a constant battle against Norodom and his ministers and provincial officials. Too weak to actively oppose the French, Norodom’s preferred

Jean Moura, French Resident in the 1870s. He was also a naval officer,

a scholar and the author of a history of Cambodia.

(Courtesy of Cambodian National Archives, Phnom Penh)

method was passive resistance. To mounting French disbelief and irritation, he would agree with their proposals for reform and then passively sabotage them. The main planks of the reform program included: the creation of private property in land, the abolition of slavery, legal and administrative restructure, and cuts to royal spending and sinecures. Although they might not have realised it, the French were following in the footsteps of the earlier 19th century Vietnamese occupiers, who had also grown frustrated by their fruitless attempts to reform the Khmer bureaucracy (see Chapter 3).

Cambodia had no private landed property in the normally accepted sense of the word. All land was crown land, the property of the king, who was indistinguishable from the state. The French saw this as a barrier to material progress. They believed it encouraged sloth and passivity on the part of the peasants, who made up the overwhelming majority of the Cambodian population. There was no doubt that it prevented the establishment of a stable taxation base for state revenues. Under the Cambodian system, which was a form of usufruct, anyone could work the land with the king’s blessing. However, should the occupants leave the land fallow for three years, anyone else was free to take it over. In return for the right to use the land, the peasants had to hand over one-tenth of their income, in kind, to the state. They were also expected to perform corvée labour, in theory for a stipulated number of days per year but in practice often at the whim of local officials, who often put the peasants to work on private projects. The system entrenched subsistence agriculture and discouraged private enterprise. The tax-in-kind system also fostered corruption because tax collectors could understate the amount of taxable farm produce in any particular year. On the other hand, the peasants could understate their actual production to avoid tax. By privatising land, the French reasoned, they could introduce fixed land taxes, which would generate a stable source of state revenue and which would be less prone to pilferage by dishonest officials.

The second aim was to abolish slavery, on both moral and pragmatic grounds. France had itself only finally abolished slavery a few decades before, but the custom flew in the face of the (in theory) cherished Rights of Man and it was also economically inefficient (as Marx had noted in Volume I of Capital, for instance). According to one estimate, 150 000 people out of a total Cambodian population of 900 000 in the 1880s were slaves. Those in bondage fell into two broad categories, hereditary slaves and debt slaves, but there were also slaves at the royal court and even in the Buddhist temples. However repugnant to modern eyes, slavery had been part of life in Cambodia since pre-Angkorean times, and Khmers—including the slaves themselves—saw it as a natural part of life, and there was no indigenous emancipation movement. Its eradication therefore proved extremely difficult.

The third major aim of the French reform program was the over-haul of the Khmer legal and administrative apparatus—later described by French administrator Gustave Janneau as ‘worm-eaten debris’. Creaking, inefficient and corrupt, the French saw it as a system of licensed robbery in which the main purpose of officials seemed to be personal enrichment at public expense. The French believed that of a potential revenue base of five million francs, two million francs either disappeared into the pockets of shady officials, or were not collected. The country was divided into 57 provinces, each of which was administered by a member of the royal family or a high mandarin, and with considerable duplication of functions between the provinces and the central government. Worse still, there was little comprehension of any difference between private and public wealth, and this attitude became more pronounced the further one scaled the ladder of status and privilege. There were no public works schemes of any consequence, with Norodom himself once questioning the need for the construction of a road because he never went to the road’s proposed destination. There was no system of education apart from limited instruction given to boys by monks at the pagodas, and no institutions of social welfare or health (in contrast to what had existed at Angkor). The legal system was often irrational, cruel and unjust. The towns were ramshackle places, little more than extended villages; the most imposing edifices in Phnom Penh, apart from Buddhist wats, were a few jerry-built brick shop houses along the riverfront.

At the top of the ramshackle social pile sat the considerable figure of the king himself. He had proven himself to be an incompetent military commander during the Pou Kombo revolt of 1866 and the French viewed him as greedy and vain. He smoked prodigious quantities of opium, downed vast quantities of wines and spirits, and concerned himself little with administrative affairs. Then there was the matter of the royal harem, which Résident Étienne Aymonier claimed consumed the ‘greatest part of the country’s revenues’. The harem was a town within a town, inhabited by Norodom’s 400–500 wives and concubines, with a total population of up to 1500 women and children, plus the palace guards and other staff. A French report of 1894 estimated the cost of maintaining Norodom at some 800 000 piastres per annum. (The piastre, issued by the private Banque de l’Indochine at Hanoi, was worth five French metropolitan francs.) We should also consider the numerous members of the royal family, each of whom was an idle belly kept full at public expense. The French were intent on drastic cuts to the royal expenditure and the introduction of a civil list.

The cost of administering Cambodia was a steady drain on the French public purse. In 1881, a French official complained that the ‘situation in Cambodia is still the worst . . . The financial disorder surpasses all bounds and the King takes all revenues for his personal use’. The Colonial Minister at Paris ordered the French authorities to take over Cambodia’s financial affairs and ensure that the king regularly put back a proportion of taxes into the costs of running the country. Norodom played for time in his usual fashion, but French patience was at an end. In March 1884, they insisted on a thoroughgoing revision of the 1863 treaty. Three months later, after further procrastination by Norodom, Governor Charles Thomson’s gunboat churned up the Mekong from Saigon with a small army of French marines and Vietnamese riflemen aboard. Thomson hauled Norodom out of bed in the predawn darkness and forced him to sign the new treaty, the first article of which committed the king to accept ‘all the administrative, judicial, financial and commercial reforms that the government of France deems useful in future’. Thomson gave Norodom a clear choice: sign or abdicate and, under force majeure, he signed.

The Great Rebellion of 1885–86

An eerie calm fell over the country. Thomson was so flushed with success that he floated the idea of annexing Cambodia outright and French officials moved confidently to introduce the program of reforms. It was a profound miscalculation. Forty years earlier, a heavy-handed campaign by the Vietnamese to ‘civilise’ the Khmer ‘barbarians’ and force them to adopt Vietnamese styles of government and administration had triggered off a desperate insurrection. Thomson’s forced mission civil-isatrice was to do just the same.

In early January 1885, Khmer rebels attacked a number of isolated French military posts, heralding a general insurrection that was to embroil almost all of the country. The central figure in the revolt was Norodom’s half-brother Prince Si Votha, a seasoned guerrilla and royal pretender who had already spent many years in the forests. The revolt united the disparate factions of the Khmer aristocracy in the common cause of driving the French back down the Mekong and won the support of the common people, tacit or otherwise. Norodom himself stayed out of the fighting, but others of his immediate family actively supported the rebels. There is also evidence that elements of the Chinese and Vietnamese minorities joined the fight against France, despite ethnic animosities between them and the Khmers. As I have written elsewhere,

For the French, it was a costly lesson in the futility of waging war against guerrillas operating on their own terrain, with natural refuge provided by forest, marsh and mountain . . . Not even 4000 heavily-armed French troops, equipped with artillery, gunboats and quick-firing guns, could quell the rebellion.

Many French soldiers fell victim to disease, while others fell under the bullets of the rebels who eluded them in the forests and fields. Stung, the French responded as many others would do in colonial wars, burning villages and terrorising the peasants whom they suspected of secretly aiding the rebels or of taking up arms themselves. By the middle of 1886, it had become clear to the French Colonial Ministry that there would have to be a negotiated solution to the conflict and that this would involve backing away from the terms imposed upon Norodom in the 1884 treaty. Moreover, the French would have to solicit the king’s support to end the uprising.

In return for a promise from the French that they would not try to impose total control over the Khmer administration, Norodom agreed to issue a proclamation for peace and to travel the country to ask the rebels to lay down their arms. Within six weeks, he had achieved what had proved impossible for the French. Resistance tapered off dramatically, although Si Votha held out intransigently in the forests until his death in 1890.

The country was largely at peace, but it was the peace of an exhausted and devastated land. The French estimated that 10 000 people had died during the revolt, but other statistics show that the Cambodian population fell from 945 000 in 1879 to 750 000 in 1888: a net loss of 195 000 people. Many of these must have died, but tens of thousands of peasants had also fled to Battambang and Siam proper, or else sought refuge in the jungle. Once again, famine and disease broke out as farmland was abandoned or devastated. It was yet another immense tragedy for a land that had never recovered from the wars, famines, deportations and insurrections earlier in the century.

France’s strategic retreat

The French had been forced to back off from their reform program, but later developments make it clear that they regarded this as a strategic retreat and not a permanent defeat. Before the insurrection they had toyed with the idea of putting Norodom’s more pliable half-brother Sisowath on the throne. Sisowath had signed a secret agreement with the French, promising his full cooperation if he were to be crowned king. Norodom had, however, proved indispensable in ending the revolt. For most Khmers he was the legitimate sovereign and the French realised that to depose him would be to overplay their hand. In any case, they reasoned, his life of excess meant that he would not live long. They would bide their time, gradually tightening the screws on the Khmer administration, careful not to force the pace lest it trigger a repeat of 1885. They also rebuilt parts of the capital, and many of its handsome colonial buildings date from the 1890s.

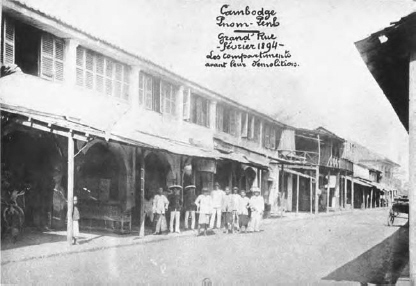

The main street in Phnom Penh, 1894, prior to the demolition of shop houses.

(Courtesy of Cambodian National Archives, Phnom Penh)

As it turned out, Norodom’s constitution was more robust than the French had hoped, and he resumed the old game of passive resistance to reform. He agreed a number of times, for instance, to abolish slavery yet the practice continued as before. By the 1890s, French anger was simmering afresh and the increasingly infirm Norodom lacked the stamina to resist. He was brow beaten by officials and one Résident Supérieur appears to have threatened him with death for recalcitrance. The French forced him to disown two of his favourite sons, one of them, Prince Yukanthor, for acting as a go-between in an ill-fated attempt to complain to the French government over his father’s treatment. The other son, Duong Chakr, had died in exile in a dusty Algerian town on the edge of the Sahara Desert. For some time before his death in 1904, Norodom was a shell of a man, kept a virtual prisoner in his palace at Phnom Penh, his health sapped by drink and opium. Perhaps he brooded on the wrongs he had done his sons and regretted his role in ending the Great Rebellion. Perhaps he even repented bringing the French to his kingdom in the first place.

Sisowath and the Franco–Khmer accord

Norodom’s successor’s loyalties were never in doubt. Succession to the Khmer throne has never been governed by strict primogeniture and for a long period before the arrival of the French, Cambodia’s kings had been chosen by Siam and/or Vietnam. The French had chosen the new king, the Obbareach, Prince Sisowath, many years previously when he had agreed to support their reform program. Shortly before his half-brother’s cremation, the 64-year-old Sisowath was crowned king (by Governor-General Paul Beau in the name of the French Republic) in a ceremony at Udong.

The French were eager to accelerate their reform program. Although stymied by what they saw as the laziness and incompetence of Khmer officialdom, the French were to achieve more in the first few years of Sisowath’s reign than they had managed in the 40 years under Norodom. Slavery was abolished, the Khmer legal code overhauled, and a system of competitive entry to the civil service introduced. The institution of private property in land, long a key plank of the reform plan, began with the introduction of a cadastral program and the distribution of title deeds. Steps were taken to root out corruption, particularly in the collection of taxes, and there was some expansion of public works schemes such as roads and bridges, government buildings and dredging of the port of Phnom Penh. A limited civil list was introduced to curb spending on minor royalty. The system of apanage, under which district administration was farmed out to members of the royal family and high mandarins, almost as individual fiefdoms, was abolished. Most importantly, a new three-tier system of local government bodies was set up under the supervision of French Résidents.

The extent of the reforms should not be overstated, however. In most respects, the French were content for Cambodia to remain an

A fine example of French colonial architecture, the former French Residence at

Battambang. (Author’s collection)

economic backwater, as they had done for most of the 40 years since the creation of the protectorate. So long as Cambodia paid its way, and public funds were used for public purposes instead of personal enrichment, they would be reasonably content. In the colonial banquet, Cambodia was a side dish compared with the Vietnamese main course.

Sisowath’s coronation in 1904, however, marked the beginning of a new stage in Franco–Khmer relations. Sisowath was a docile supporter of France, although he had proved himself a competent and physically courageous military commander during the Pou Kombo insurrection. His pliability reflected a pragmatic mix of self-interest, resignation to the facts of Realpolitik, a genuine respect for French culture, and faith in the ability of France to protect his kingdom. His reign, and that of his son Monivong (who succeeded Sisowath after his death in 1927) was one of Franco–Khmer accord, marked by social peace and stability—a break from the more turbulent Norodom years. The palace

Cambodia's shifting borders in the colonial era

intrigues of supporters of the Norodom wing of the royal family, who felt one of them should have inherited the throne, were ineffectual. Influential civil servants such as Thiounn were resolute Francophiles.

Sisowath’s loyalty to France was cemented early in his reign when in 1906 he undertook an extended tour of France, his first and last overseas journey apart from his youthful sojourn as a guest-hostage of the Siamese king at Bangkok. Sisowath was delighted by what he saw. Cheering crowds of ordinary French folk lined the roads to welcome him, there were dazzling displays of military power, and the President of the Republic received him in the Elysée Palace at Paris. Equally impressive were the civic and industrial wonders of the protector-nation. He committed a major diplomatic gaffe in France when he called publicly for the restoration of the lost provinces of Battambang and Angkor to Cambodia, but he was rewarded soon afterwards when in 1908, after delicate negotiations, Siam agreed to their return. Shortly afterwards—following an unsuccessful anti-French revolt by followers of the Apheuvongs family who had governed the provinces on behalf of Siam since 1795—a French archaeological team began the painstaking task of restoring the Angkor ruins. These had remained a symbol of Khmerité—‘Khmerness’—since their loss over a century before, and with their return Cambodia was almost whole again.

Sisowath’s gratitude showed in his wholehearted support for the French cause during the Great War of 1914–18. Some 2000 Cambodians served as tirailleurs (sharpshooters or light infantrymen) in French colonial regiments in Europe, while some hundreds of Khmers joined the hundreds of thousands of colonial workers in the munitions factories of France. Members of the Khmer Krom minority from Vietnam also served in other Indochinese regiments. A number of Khmers won medals for bravery in battles on the western front and in the Balkans. A number of members of the royal family served in the armed forces. These included Sisowath’s eldest son, Prince Monivong, who trained at the Saint-Maixent military academy and rose to brigadier’s rank. Another prince, Leng Sisowath, left his bones in a French military cemetery. However,

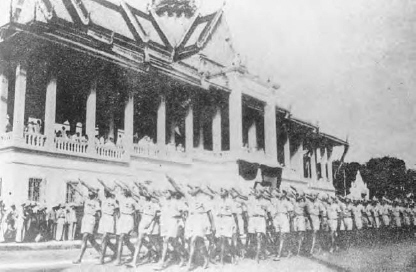

Young Khmers rally to the colours, Phnom Penh circa 1914. The statuary on the Wat

Phnom behind them commemorates the return of the lost provinces from Siam in 1907.

(Courtesy Archives d’Outre-Mer, Aix-en-Provence)

Monivong did not serve at the front because of the possibility that he might be needed to succeed his elderly father on the throne.

The 1916 Affair

The sacrifices of the Khmer tirailleurs should not blind us to the fact that the majority of the common people did not share Sisowath’s enthusiasm for France’s war. Recruitment fell short of targets and the authorities resorted to heavy-handed methods to meet quotas. The resulting resentment combined with long-brewing discontent over rising levels of taxation and abuse of the corvée regulations and sparked off an extraordinary movement of peasant protest that the French authorities dubbed the 1916 Affair. There is some evidence to suggest that dissident circles associated with the exiled Prince Yukanthor, the rebellious anti-French son of Norodom, had a hand in stirring up discontent, and the synchronicity of events and striking similarity of demands across the country suggests the existence of some kind of organisation or resistance network. Some 100 000 peasants flocked into the capital from the provinces, and although there were some instances of violence against Khmer bureaucrats and Chinese traders and one recorded assault on a French administrative office, in the main the demonstrations were peaceful.

What is striking about the Affair is that, on the whole, the tens of thousands of peasants involved ignored the French authorities and took their grievances directly to the king. The vast majority of them would never have seen Sisowath—he was as remote for them as the man in the moon—yet they trusted him because of their faith in the institution of kingship. The French were largely invisible, particularly in the countryside where most Khmers lived, and the peasants blamed the Khmer bureaucracy for the abuses they suffered, despite the efforts of more political elements to turn the protests into an anti-French crusade. The peasants saw the king as a devaraja with supernatural powers: a being quite disconnected from the state apparatchiks who collected the taxes, forced them to labour on the roads and often lined their own pockets in the process. In fact, the French administration had been increasing taxes for some years, but because Khmer officials collected these the peasants held them responsible.

The movement ebbed as swiftly as it had begun, after the king promised to investigate the peasants’ grievances and the French authorities agreed to tax relief and to end some of the more egregious abuses of corvée. The Affair ended with tragedy, however. The authoritarian Résident Supérieur François Baudoin—perhaps fearing a repeat of the 1885 rebellion—ordered a crackdown. ‘Agitators’ were hunted down and many received long prison terms. There were reports of soldiers machine-gunning crowds and tossing the corpses into the river, although these were printed in anti-regime papers and should be taken with caution. We cannot say with certainty how many died: the lowest estimates claim half a dozen slain and Baudoin himself admitted 21 deaths. It is likely that scores or even hundreds perished.

French power was stretched thin during World War I, with many troops and officials called to the colours in Europe. Yet despite the spectre of 1885, France’s grip was never seriously threatened during this period. A combination of repression and amelioration of the tax and corvée burden—which the peasants probably attributed to the king’s good influence—put the lid on further large-scale manifestations of popular discontent. Nor were worries that returning soldiers and workers might act as a conduit for radical ideas borne out, although some Khmer soldiers did become moderate nationalist politicians in later decades. The Allied victory in Europe probably enhanced France’s prestige among the general population, and further strengthened ties with the Khmer elite. The French built a huge commemorative monument in Phnom Penh (later demolished by the Pol Pot regime) and the war hero Marshal Joffe made a triumphal tour of the country, including to the Angkor ruins. It was the beginning of the zenith of French power in the kingdom, a period described by the Cambodian writer Huy Kanthoul as ‘a kind of belle époque’.

By the 1920s the economic austerity of the war years had lifted and there was something of an economic boom, marked by increased spending on public works, health and education, and by the development of large-scale rubber plantations on the left bank of the Mekong, upstream from Phnom Penh. The Angkor restoration project had continued throughout the period, and under the able direction of French scholar and linguist Suzanne Karpelès a Buddhist Institute was set up to study and preserve Cambodian religious culture. There was also something of a revival of traditional Cambodian arts and crafts, many of which had been threatened with extinction by cheap mass-produced imports.

The relative prosperity and progress of the 1920s, however, came to a sharp end with the onset of the Great Depression. The economy stagnated, public expenditure was slashed to balance budgets and there

This French-built commemorative monument to the Allied victory in

World War I was later demolished by the Pol Pot regime.

(Courtesy David Chandler)

was great destitution among the Khmers. On the eve of World War II, though, the economy was on the mend again and many colonial officials and settlers must have believed that the belle époque would continue for many years.

The Bokor and Bardez Affairs

But there was a dark downside to this period. The French Résidents gave the police a free hand to use brutal methods against the Asian populations, and ratcheted up taxation levels in the 1920s to cancel out the concessions granted as a result of the 1916 Affair. The French authorities also encouraged increased Vietnamese immigration to provide indentured labour for the plantations and construction projects. Living and working conditions on the plantations were often appalling, to judge by the French labour inspectors’ reports and by the strikes and mass desertions that were commonplace. Not surprisingly, the Khmers tended to shun plantation work. Two incidents underline the arrogance and contempt of French officialdom for the common folk during this period, the Bardez Affair and the construction of the Bokor hill station.

After World War I, Résident Supérieur François Baudoin decided to build a French pleasure palace at Bokor atop a mountain overlooking the Gulf of Siam behind Kampot. It would rival the British efforts at Poona. There was to be a grand hotel, a casino, tennis courts, gardens and paths along which colons and their wives could take the cool mountain air. At an altitude of over 1000 metres, European fruits and vegetables thrived, to the delight of French palates. Baudoin ordered construction of a special bungalow for himself within the complex. The project consumed an enormous slice of government revenues and led to protests by the radical press at Saigon and in France at the excesses of Baudoin, whom they dubbed the ‘tyrant of Cambodia’. The building of Bokor also claimed many lives, particularly on construction of the road, which snaked up through the jungle-clad mountainsides from Kampot. The authorities never published any figures of the death toll, but the French Saigon press claimed there were between 900 and 2000 dead and the novelist Marguerite Duras recalls her settler mother’s horror at the brutality meted out to workers.

The French built Bokor to benefit themselves, but the peasants paid for it in blood and sweat, and in taxes. Taxation levels crept upwards again in the early 1920s and caused widespread discontent. This led to tragedy in 1925, when Baudoin dispatched a peppery ‘trouble-shooter’ called Félix Louis Bardez to the Khmer village of Kraang Leav, in the Kompong Chhnang district, to investigate complaints of excessive taxation. Bardez, a decorated former non-commissioned officer and long-serving colonial official, was not renowned for his tact. He summoned the villagers and, via his interpreter, subjected them to an insulting harangue. Later, when the sun rose high in the sky and after the consumption of quantities of palm wine, the peasants battered Bardez, his interpreter and a Khmer militiaman to death. Although the administration claimed that the murders were in no way political, dissident European elements in Saigon were able to turn the subsequent murder trials into an indictment of the Baudoin administration. Be that as it may, the assassination of Résident Bardez was the first overtly political murder of a French official for many years, and it was to be the last until the twilight days of the Protectorate after World War II. Discontent was more likely to be channelled into endemic banditry or into ethnic strife between Khmers and Vietnamese or Chinese. Indeed, anti-Vietnamese feeling has coloured Cambodian nationalism from its beginnings in the 1930s until the present day.

Cambodian nationalism’s hesitant beginnings

By the 1920s, the political passions of their homelands had spread to the Chinese and Vietnamese minorities in Cambodia. These minorities were substantial, particularly in Phnom Penh where the population was fairly evenly divided between Khmers, Chinese and Vietnamese. After World War I, the tenor of the Chinese and Vietnamese political and quasi-political associations was distinctly anti-French and anti-colonial. Affiliates of the Chinese Nationalist Kuomintang took root in Phnom Penh after the war, and more militant, illegal Marxist-inspired tracts appeared among the city’s Vietnamese population.

From the late 1920s, revolutionary cells were set up and attracted much police attention. There were strikes among building workers in the capital and persistent agitation against bad conditions on the rubber plantations. In general, the Khmers stood aloof from these developments, seemingly immune to the clarion calls of socialism and nationalism. However, there was a gradual change in consciousness, and although this was not always overtly political it arguably laid the groundwork for Khmer nationalism.

Sirowath’s royal boat, Phnom Penh, in the 1920s was a showpiece for the revival

of traditional Cambodian arts and crafts.

(Author’s collection)

During the 1920s, a number of Khmer-language cultural magazines appeared. These were apolitical, but they did assist in the formation of a Cambodian cultural–ethnic–political identity. In 1936, a group of youngish Khmer intellectuals began publication of the Khmer-language magazine Nagaravatta (Angkor Wat in English) and a number of Cambodian novels and volumes of poetry appeared. This movement was ambivalent towards the French because, as Huy Kanthoul has pointed out, the Khmers had tended to look towards the French as protectors against their neighbours. The perceived enemy during this period was the Vietnamese, not the French, and what direct political comment we find in the pages of Nagaravatta and other publications is charged with the ‘politics of envy’ against the immigrants from down the Mekong.

While it would be drawing a long bow to claim that the French deliberately imported the Vietnamese in order to play a game of divide and rule, the presence of so large a minority led to ethnic friction, and the French made opportunistic use of it when it suited them (just as they played off the Khmer Krom minority against the Vietnamese in Cochin-China). Upon the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, Khmer nationalism was weak and unfocused, with most Khmers either indifferent to the French or well disposed towards them. Even today there are some very old Khmers who look back with nostalgia to the colonial era. However, war and French humiliation at Asian hands during the Japanese occupation were to change the political situation forever, and trigger a qualitative leap in consciousness that was to lead to independence within less than a decade after 1945.

War, Japanese occupation and French

humiliation

The fall of France came swiftly in June 1940. The victorious Germans partitioned the country into a nominally independent state with its capital at Vichy in the south and a directly occupied zone in the north. The authorities in some of France’s overseas colonies heeded the call of General de Gaulle to continue resistance, but many others, including those in Indochina, declared their loyalty to the quasi-fascist pro-Axis regime at Vichy, led by the geriatric war hero Philippe Pétain.

In the case of the French Indochina Governor-General at Hanoi, Admiral Jean Decoux, it was perhaps a matter of discretion being the better part of valour to support Vichy. Battle-hardened Japanese armies were on the northern borders of Tonkin after fighting their way south through China, and the military forces at Decoux’s disposal were at best mediocre in the case of his European troops, and downright untrustworthy in the case of his ‘native’ infantrymen. The Japanese, too, were

Members of the Yuvan youth organisation march in support of the Vichy government

in France. (Author’s collection)

Vichy’s nominal allies, however terrifying they appeared to Decoux’s ramshackle army. Decoux became a zealous Vichyite, enforcing Pétain’s version of the racist Nuremberg Laws, setting up concentration camps and enforcing other tawdry symbols of European fascism in his tropical fiefdom: the goose-step, the fascist salute and ritualised chanting of Pétain’s name. As if at a word of command, the French-language press in Indochina switched from pro-Allied propaganda to hate-filled invective against Jews and the English, and gloated over Allied reversals. This calls into question Decoux’s later claims to have merely gone through the motions to placate the Japanese.

The Japanese aim was to strike southwards into Southeast Asia in order to gain control of the oil, tin and tropical commodities they required for the Home Islands and to run their war machine. The French government readily agreed to their request to station troops throughout Indochina, and also to provide them with rubber, coal and other products. They were scarcely in any position to refuse. For their part, the Japanese were content to leave the day-to-day administration of Indochina to the despised whites, so that they could concentrate on their war aims. It was a marriage of convenience that was to last until the dying days of the war.

The French capitulation was a devastating blow to French morale in the colony, and it must have given the Francophile Khmer elite cause for grave concern. Worse was to come in early 1941, when the Japanese brokered a humiliating agreement between France and Siam—by now renamed Thailand—following a short-lived war. The war had broken out in late 1940, with the Thais taking advantage of France’s weakness to demand the handover of Cambodia’s western provinces, which they had ceded in 1908. While the land war was inconclusive, the French had inflicted a stinging defeat on the Thai navy at the Battle of Koh Chang in the Gulf of Siam, and might have expected a more favourable outcome than that imposed by Japan. However, despite its nominal alliance with Vichy, Japan’s underlying aim was to undermine western colonial power in Asia, regardless of its political complexion. They awarded Thailand almost all of the territories she had asked for, with the exception of the area around the Angkor ruins, which France argued bitterly to retain.

The Cambodians had tolerated the French and many, especially in the elite, had welcomed them, so long as they acted as protectors of srok khmer. Now, their protector’s sword and shield were broken, and the ancient predators were at the gates of the kingdom. Perception of France’s weakness led on one hand to profound disillusionment and depression, but on the other to the growth of nationalist sentiment and to a new confidence that Asians could defeat the almighty Europeans. The former effect was most pronounced in the case of King Monivong, who had succeeded his father to the throne in 1927. Monivong could pass as a ‘brown Frenchman’, for although he never lost his identity as a Khmer, he spoke fluent French and had adopted many western customs. He had risen to the rank of brigadier in the French army and although he was a figurehead who played relatively little part in government affairs, he was intensely loyal to France. When the news came through of the forced cession of Battambang and Siem Reap provinces, Monivong was plunged into deep gloom and retired to his estates at Bokor where he refused to meet with French officials and even ‘forgot’ their language. He died soon afterwards in the company of his favourite concubine, Saloth Roeung, the sister of a man called Saloth Sar who was later known to the world as Pol Pot.

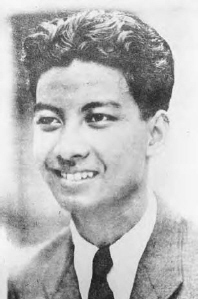

While Monivong died without hope, the French humiliation had electrified the young Cambodian intellectuals associated with the magazine Nagaravatta, and nationalist sentiment swept through some circles of the Buddhist sangha. Nagaravatta openly criticised the French authorities, who responded with heavy censorship before banning it outright in 1942. Monivong’s successor to the throne, a baby-faced 19-year-old prince from the Norodom wing of the family, made little impression on politics at the time. The young Norodom Sihanouk, whom Decoux had installed on the throne in the belief that he would be a docile puppet, initially surpassed their best expectations, preferring to chase girls and watch films than worry himself with affairs of state or nationalist politics. Decoux was not the first person to underestimate him, but Sihanouk’s nature had not formed and it is doubtful that he had a subversive thought in his head at the time, regardless of his later claims. Another young man called Son Ngoc Thanh, a Khmer Krom from the lower delta and a member of the Nagaravatta circle, came to symbolise Cambodian nationalism at this stage.

The Vichy regime in Indochina was viciously repressive. The police rounded up thousands of real and imagined opponents and interned them in prisons and concentration camps, including the Pich Nil camp in the coastal mountains south of Phnom Penh. It was also a period of mounting austerity with widespread shortages of food and clothing and, according to Cambodian nationalists, taxation grew steadily heavier. The Allied navies cut Indochina’s overseas trade routes and the Japanese occupation forces requisitioned much of the country’s food and

The young Norodom Sihanouk.

(Author’s collection)

plantation products for their own consumption and for export to the Home Islands. This built up a head of resentment against the French, whom the Khmers held responsible for the shortages.

The Vichy political regime was also contradictory. While the French authorities were repressive and insensitive, they were also conscious of their extreme weakness, vis-à-vis both the Japanese and their colonial subjects. The Japanese had ousted the British and Dutch colonial authorities in Malaya and the East Indies and their rhetoric was stridently anti-European. The French must have been fearful of the longer-term intentions of their nominal allies. They responded by attempting to mobilise the Khmers behind their regime. They encouraged Khmerité, and while this was in the main cultural and meant to bolster French rule, it was to have unforeseen consequences. Vichy’s quasi-fascist trappings were visible everywhere, at least in the towns, with huge portraits of Pétain on the façades of buildings and exhortations to uphold the imperatives of ‘Work, Family and Fatherland’. Khmer boys were encouraged to join the scouting movement and a kind of mass youth militia, the Yuvan, was set up to mobilise young Cambodians behind the regime. However, these organisations brought young Khmers out of their families and villages and gave them an inkling of potential collective strength that would be turned against the colonialists.

The Revolt of the Parasols

Despite their promotion of Khmerité the French were inconsistent. In 1941, the French authorities decided to replace the ancient Khmer script (based on Sanskrit) with a new romanised script known as quoc ngu khmer after the reformed Vietnamese script.3 The move caused widespread indignation, particularly in the Buddhist sangha and in the proto-nationalist circles around Son Ngoc Thanh and Nagaravatta. Son Ngoc Thanh secretly negotiated with the Japanese who, while they counselled prudence, did not discourage his nationalist ambitions. The quoc ngu khmer issue provided the Cambodian dissidents with a focus for popular discontent; on the one hand, the French encouraged Khmerité, yet on the other they threatened the age-old Khmer customs.

In July 1942, a nationalist monk called Hem Chieu delivered a vitriolic anti-French sermon to a group of Cambodian tirailleurs in a Phnom Penh wat. An informer tipped off the French police, who arrested Hem Chieu and a number of other monks and lay nationalists. In response, several thousand angry Khmers, including monks with their distinctive orange robes and parasols, marched on the Résidence Supérieure demanding the prisoners’ release. A riot ensued, in which a number of police and demonstrators were injured and more arrests made. Further bloodshed was probably deterred by the presence of Japanese military police, the Kempetei, who stood by but did not intervene. The event entered Khmer political folklore as the Revolt of the Parasols, after the monks’ sunshades. In another country, the incident might have been relatively unremarkable, but in hitherto docile Cambodia it was a significant milestone on the road to national independence. Afterwards, the colonial authorities launched a general crackdown, banned Nagaravatta and sentenced several of the perceived ringleaders to death. The French government commuted these terms to life imprisonment on the prison island of Poulo Condore in the South China Sea. There, tutored by Vietnamese nationalist prisoners, the Khmers gained an advanced anti-colonial political education. Son Ngoc Thanh, meanwhile, had sought sanctuary with the Japanese, who spirited him out of the country to Japan, where he was to remain until the last months of the war, remaining in postal contact with his supporters in Cambodia.

With hindsight, it is clear that the high tide of Japanese expansion in Southeast Asia and the Pacific came in the months immediately after the aerial attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and the fall of Singapore in early 1942. Thereafter, with her supply lines dangerously over-extended, Japan was to face the full might of American military and industrial power, and soon suffered big defeats at the Battles of Midway and the Coral Sea. The D-day landings by the Allies in France in the summer of 1944 led rapidly to the liberation of Paris and the fall of Vichy. Governor-General Decoux decided it was time to indicate that he was prepared to change his political spots and made a secret agreement to back the Allies when the time came. Meanwhile, he dropped the fascist paraphernalia and pro-Axis rhetoric and although he was anxious not to provoke the Japanese these changes raised their suspicions. With Vichy dead and a new anti-Axis government at Paris, Decoux’s usefulness to the Japanese was in question.

The Japanese coup and puppet independence

On 9 March 1945, the Japanese staged an Indochina-wide coup de force against the French, crushing feeble efforts at resistance with ease. The brutal military police of the Kempetei threw the French soldiers and civilians into concentration camps, treating them with neglect and great cruelty, and murdered some in the streets of Phnom Penh. The Japanese government also decided that the time had come for King Sihanouk to declare independence, as had already happened in Burma. They took this step both from political conviction and from the desire to focus their efforts on the military struggle, free of administrative distractions. Sihanouk recalls that he was greatly amazed when Kubota, the Japanese special advisor to Cambodia, directed him to declare his country’s independence from France. This he did, in an unusually restrained broadcast; he must have been under no illusions about the coming Allied victory and couched his statement in guarded terms rather than a ringing declaration.

Sihanouk’s new government trod warily, doing little beyond reversing the quoc ngu khmer decree and changing street names. He pointedly ignored the newly liberated Khmer prisoners when they arrived back from Poulo Condore, and offered them no posts in his government. Perhaps he saw them as a potential threat to his position, but it is also probable that he wished to distance himself from people whom the Allies would call traitors upon their inevitable return to Indochina. Later, seeking to cast himself as the sole architect of Cambodian independence, he attempted to write them out of history.

In May 1945, Son Ngoc Thanh returned from exile aboard a Japanese bomber and enormous crowds of supporters welcomed him at Pochentong airport. Such was Thanh’s prestige among Khmers and standing with the Japanese that Sihanouk stifled his jealousy and appointed his rival as Foreign Minister. Nationalist firebrand or not, Thanh did little to change the timid course of the government at this stage, although he appears to have been an enthusiastic collaborator with the Japanese. He was instrumental, however, in setting up a nationalist militia, the Greenshirts, as the core of a projected national army.

When the first atomic bomb fell on Japan on 6 August, Thanh’s supporters grew restless. Although the Japanese army in Indochina was intact, Germany had already capitulated. Two days later, the USSR entered the Pacific War. If the hard-line nationalists were to take control of government, they had to act soon before Japan’s collapse. On 9 August, the day the second atomic bomb fell on Nagasaki, a group of militiamen burst into the royal palace, demanding the removal of old retainers and bureaucrats from the government and their replacement with nationalists. It amounted to a putsch. Some of the old guard ministers retained their posts, but Son Ngoc Thanh took up the post of prime minister and other nationalists took key positions.

The whole affair had strong comic opera overtones. Son Ngoc Thanh insisted on the centrality of the alliance with Japan even as Tokyo was on the brink of unconditional surrender and news of the horror of Nagasaki and Hiroshima spread round the world. It was only a matter of time before the French returned and they would not tolerate what they would see as a government of Japanese puppets and traitors. In the meantime, Thanh took few initiatives apart from organising a referendum on the question of independence and the legitimacy of his government. The vote was Stalinist style, with 99.999 per cent voting for Thanh, but it probably did reflect a genuine desire for independence. It was also the first time that a government had allowed the Khmers to vote for anything.

The return of the French and the fall of Son

Ngoc Thanh

The end came inevitably for Thanh’s government. An advance guard of British troops flew into Pochentong airport in early October, soon followed by General Jacques Leclerc, the French commander in Indochina. Leclerc arrested Thanh at gunpoint and dragged him off to prison in Saigon, to the slightly guilty bemusement of the British commander, who had regarded Thanh as a ‘silly little man’. Sihanouk assured the Allies that ‘the Cambodian people had always loved France’. The French, for their part, did not publicly hold Sihanouk’s lapse against him. Most likely they were aware of the deep reverence with which the Khmers viewed the monarchy and were unwilling to stoke nationalist fires by moving against him.

The French government was aware that there had been a sea change in political consciousness in Southeast Asia. The hothouse of war and Japanese occupation had caused a flowering of nationalism across the region. The eternal colonial afternoon of the 1930s was over. The Cambodians had enjoyed a kind of independence and they saw no reason why colonialism should return. The British were already preparing to depart from Burma. The Roosevelt administration in the United States had been openly hostile to the reimposition of French colonial rule in Indochina and the Cold War had not yet undermined American sympathy for Asian peoples’ national aspirations. President Harry Truman was committed to honour the US promise to quit the Philippines by 1946. The Viet Minh controlled much of neighbouring Vietnam and their uneasy truce with France would not last long.

In this atmosphere, it was prudent for France to make a number of reforms. In the balance of things, it was better for them to work with Sihanouk and to contain nationalist feeling by granting some autonomy to Cambodia. In early January 1946, Sihanouk’s uncle Prince Monireth and Major-General Marcel Alessandri signed a provisional agreement that granted increased powers to the Cambodian government. The old colonial titles would be abolished and a high commissioner would be responsible for supervision of the Cambodian authorities. Plans were also made for an elected assembly as part of a constitutional monarchy. It was not real independence, though, as control over military affairs and foreign relations, finances, customs and excise, posts and telegraphs and railways remained in French hands, and French officials would supervise most aspects of the Khmer government, bureaucracy and the police.

The agreement meant that the future Cambodian government would have less power than the Japanese had allowed to Sihanouk and Son Ngoc Thanh, but it was an advance over what had existed until March 1945. The Khmers could look forward, perhaps, to the gradual extension of their government’s powers. Cambodia’s first ever elections were scheduled for April 1946 and a number of political parties emerged to contest them. Most of these parties represented the interests of factions, extended families, and cliques within the Khmer elite, and some of them existed for little more than the personal self-enrichment of their tiny memberships. Given that Cambodia had no experience of democracy, and that political parties had never existed before, this was not surprising. Such parties were fluid and transient and won few votes, despite financial backing from the French administration. In the lead-up to the 1946 elections, two major parties crystallised, the Liberals and the Democrats, and these became, roughly, the right and the left inside the national assembly and were to dominate parliamentary politics until Sihanouk amalgamated most of the parties after independence.

The Democrat ascendancy

Despite their name, the Liberals were conservatives, with strong ties to the monarchy, the Khmer elite and the French. Founded by Prince Norodom Norindeth, their most important supporter was King Sihanouk, who became a key political player during this period. However, despite their influential backers in the Khmer elite, the support of the king and the covert backing of the French administration, the Liberals and other rightist parties were perennial also-rans in all the elections in the period up to independence and were never a serious electoral threat to the Democrats. Eventually, frustrated by their inability to win government by democratic means, Sihanouk and his allies staged a coup to remove the Democrats from office—but this was some years in the future, and for the time being there was a flowering of relative democracy in the country. Before the war, the few publications that appeared were subject to approval by the French administration and could fall victim to the censor’s blue pencil for trifling reasons. In the postwar years, France’s new approach saw the appearance of numerous Khmer and French language newspapers.

The first leader of the Democrats, Prince Sisowath Yuthevong, was perhaps the ablest political figure during this period, with the possible exception of the wily Sihanouk. A genuine intellectual with postgraduate degrees in astronomy and mathematics from French universities, Yuthevong had a real commitment to the development of his country. Cursed with ill health, he died young, to the great misfortune of his country. Yuthevong’s fledgling party soon attracted support from former members of the Nagaravatta circle, educated civil servants and intellectuals such as Huy Kanthoul, and from the peasants and town-dwellers.

Whereas the Liberals stood for the status quo, with all of its attendant privileges for their supporters, the Democrats adhered to many of the policies of the French Socialist Party. They stood, broadly, for a modernised and democratic Cambodia as an independent state and constitutional monarchy within the French Union. Concretely, this meant universal suffrage, a bicameral parliament and the gradual transfer of power from the French administration. Unlike the anti-French Khmer Issarak guerrillas, who were already ambushing French patrols in the countryside, the Democrats believed it was possible to win independence by peaceful and constitutional means.

The ideological differences between the Liberals and the Democrats also translated into a different style of political organising. For the first time in Cambodian history, a political organisation reached out to the common people and sought to enrol them in its ranks. This gave the Democrats the edge over the rightist parties, who believed in authoritarian government and the divine right of kings, and saw politics as a vehicle for self-enrichment. In the Liberals’ elitist view, the people were a passive mass, not a power base. By contrast, right from their inception in early 1946, the Democrats began to build up a party organisation that stretched down to village level. Their message found ready listeners among the peasants and town poor who had been radicalised during the war and Japanese occupation.

The Democrats won a landslide victory in the April 1946 elections. With 50 seats, they dwarfed the 14 Liberals and the three independents in the National Assembly. Moreover, they had won despite a ‘dirty tricks’ campaign and shameless vote-buying by their opponents. This was to be the pattern up until Cambodia’s last relatively free election in 1951. Even before the newly elected members took their seats in this first Cambodian parliament, the king’s uncle, Prince Monireth, had written the draft of a constitution for the country. The first task of the newly elected national assembly was to ratify the draft, but if the Khmer elite and the French administration had expected it to be rubber stamped they were mistaken. Prince Monireth was an austere individual who had moved away from youthful liberalism to a more traditional view of authority, and this was reflected in his draft. After stormy debates, the Democrats made major revisions to the document and produced something more in keeping with their ideals. Sihanouk, who was in a somewhat democratic mood at the time, ratified the constitution in May 1947. The constitution enshrined the rule of law, guaranteed basic rights and liberties, and placed limits on the powers of the monarchy. It was not a revolutionary document, but it was nevertheless a significant departure from absolute monarchy and authoritarian colonial rule.

Unfortunately, Prince Yuthevong did not long survive the ratification. Sickly from childhood, he retired for a holiday at the resort town of Kep on the Gulf coast, only to contract malaria and to die in July 1947. As Huy Kanthoul later lamented, his death was ‘an almost irreparable loss’ to the Democratic Party. One could go further. In a political climate all too often marked by corruption and unprincipled intrigue, he stood out as an honest man—and one with great moral authority among Khmers. Had he lived he might have acted as a counterweight to Sihanouk’s increasingly authoritarian tendencies. Sadly, many Khmers today seem to have forgotten his name, not the least because of a concerted effort by Sihanouk to belittle him and erase his name from Cambodia’s history.

The return of the lost provinces of Battambang and Siem Reap later in the year must have lightened the gloom felt by Yuthevong’s fellow Democrats. The Japanese had awarded the provinces to Thailand in 1941 as part of a treaty they imposed to end the Franco–Thai War. Their return largely restored Cambodian territorial integrity, although Cambodian grievances over the loss of Khmer lands and people in the lower delta to Vietnam remained. The following years, however, were ones of tumult and change for Cambodia. Fighting between French soldiers and Issarak guerrillas intensified and the Viet Minh controlled much of the eastern part of the countryside. Parliamentary politics, too, was proving to be much more problematic than first expected, with horse-trading, bribery and corruption widespread.

The elections of December 1947 once again returned an absolute majority for the Democrats, who could look forward in theory to a four-year term in office. However, history has shown that huge and repeated government majorities often carry the seeds of corruption within them. Minority voices can be quelled and debate cut short by the parliamentary guillotine. Many MPs from across the party spectrum used their office to line their pockets at public expense. One of the most ambitious schemers was a Democrat called Yem Sambaur, who destroyed vital evidence in a scandal involving the illegal sale of rationed commodities. Other MPs and members of the royal family ran illegal casinos and enjoyed immunity from arrest due to the protection of the corrupt police chief Lon Nol, who was to cast a long shadow over Cambodian political and military affairs.

Parliamentary horse-trading and intrigue

The Democrats lost their parliamentary majority in 1949 when Yem Sambaur left the party and set up his own group. Sambaur afterwards led an unstable coalition government until the majority of MPs backed a censure motion against him. Sihanouk dissolved parliament, but to the disgust of the Democratic opposition he refused to call fresh elections and re-installed Sambaur in office. Sihanouk’s behaviour was an ominous portent of his willingness to bend and break the constitution to put his toadies in office and enhance his own power. Anger over his manoeuvres was perhaps forgotten, however, by the passage of a new Franco–Khmer treaty, signed in November 1949, which established Cambodia as an ‘independent state’ within the French Union, with more powers passing over to the Cambodian government. The French, however, remained the real masters of the country and many countries refused to recognise Cambodia as a fully sovereign state.

Meanwhile, political intrigues escalated into violence on the streets of Phnom Penh. In January 1950, someone lobbed a hand grenade into the Phnom Penh headquarters of the Democratic Party, killing a party leader called Ieu Koeus. The circumstances surrounding the murder were murky and many of the huge crowd that followed Koeus’ funeral cortège believed that Yem Sambaur government ministers were implicated. Others blamed the French, who for their part blamed the Issaraks. Meanwhile, the economy deteriorated and public services sank into disrepair. Further scandals followed and in May 1950, Yem Sambaur was so hated that he resigned his post. Even then, Sihanouk declined to call an election. He directed Prince Sisowath Monipong, one of the deceased King Monivong’s sons, to form a new cabinet. Monipong was competent but aware that he lacked a popular mandate. Sihanouk finally agreed to call fresh elections, but only after a bizarre charade in which he publicly and histrionically declared he was about to abdicate; a crude but effective Bonapartist ploy in which he invited the people, over the heads of constitutional authority, to ‘dissuade’ him.

The Huy Kanthoul government

The Democrats won a convincing victory in the elections of September 1951, despite Sihanouk’s public support for the rightist candidates. The French, too, had backed the Liberals with money and materials, but the people again rejected them. The Democrats won 54 of the 78 seats in the National Assembly. The Liberals limped in with 18 seats and smaller rightist parties made up the rest. The verdict on Yem Sambaur was crushing: his party won not a single seat.

The Democrat leader Huy Kanthoul formed a new government in October 1951. Had Sihanouk and the opposition parties respected the constitution, Huy Kanthoul could have expected to remain in power until October 1955. As it turned out, Huy Kanthoul’s government was to be the last freely elected Cambodian government for many decades. From its inception, intriguers such as Lon Nol and Yem Sambaur worked to undermine it. The policeman-cum-politician Lon Nol was an unsavoury individual—according to French police files, he had murdered a political opponent at the Pich Nil concentration camp back in 1945— and he had little respect for the democratic process. Even without the schemers, the new government faced a difficult time; the economy was stagnant and the war against the Issaraks in the countryside raged unabated. Huy Kanthoul’s problems were compounded by Son Ngoc Thanh’s return from his French exile in October 1951. Again, huge crowds flocked to meet Thanh at Pochentong and his reception must have bolstered his radical mood. He founded a nationalist newspaper and gave vitriolic anti-French diatribes that embarrassed the Kanthoul government. He did not stay long in Phnom Penh, however, and soon slipped away to join the Issarak guerrillas in the countryside.

Thereafter, the government’s critics stepped up their accusations that Huy Kanthoul was in league with the Issaraks. Lon Nol was one of the more vociferous of these critics and his behaviour crossed the line between dissent and subversion. In one instance he drove round the capital with a loudspeaker, openly calling for the overthrow of the government. For his pains, he spent a night in the police cells with a number of his allies. It was scarcely draconian punishment and his feigned outrage was ironic, given his penchant for robust policing. Sihanouk added his squeaky voice to the chorus, denouncing what he called the Democrats’ disloyalty and alluding to a secret republican agenda. The French joined in too, alleging that the government was unwilling to take the necessary stern measures against the Issaraks. The political right were clearly in the mood for a coup.

The coup came in June 1952. Although Sihanouk denied it, it is most likely that he plotted with the French high commissioner to remove Huy Kanthoul’s government. It is not credible that heavily armed French troops equipped with tanks just happened to be in Phnom Penh on the day of the coup, all the more so since they surrounded the National Assembly building while its sacking took place. This time, Sihanouk did not govern via an intermediary such as Yem Sambaur. He assumed power directly and dissolved parliament. Huy Kanthoul, the leader of the democratically elected government, went into exile in France and his political career was effectively over. Sihanouk’s unelected cabinet largely consisted of the old cronies, placemen and rightist intriguers who had destabilised the elected government in the first place. A wave of strikes and protests erupted, but Sihanouk was intransigent. Many of the protest ‘ringleaders’ were detained without trial and others arraigned on trumped up charges, a great irony given the claim that Huy Kanthoul was a dictator for locking up Lon Nol and his cronies overnight.

The brave democratic experiment was over. Sihanouk would govern either directly or through proxies for the next 18 years, until he was himself removed in a pro-US coup led by the perennial schemer Lon Nol. It was not surprising that the French were involved in the removal of Huy Kanthoul, given the oppressive nature of their rule. Sihanouk had learned too well the anti-democratic tunes of Cambodia’s colonial masters. However, it is to his credit that he soon afterwards embarked on a ‘royal crusade’ that would lead the country to independence.

The Royal Crusade for Independence

Sihanouk launched his ‘crusade’ in quixotic style in March 1953. Irritated by French refusals to grant the concessions of a new protocol on self-government agreed to in early May 1952, the king flew to Paris to argue his case with the French President, Vincent Auriol. The lack of progress was undermining Sihanouk’s nationalist credentials and giving ammunition to the Issarak and Viet Minh guerrillas, who denounced

Among the crowd waiting to welcome Sihanouk on his return from Paris was this

group of Buddhist monks. (Courtesy National Archives of Australia)

him as a colonialist stooge. Time was running out for the French in Indochina. French public opinion had swung against the war with the Viet Minh and although France’s catastrophic military defeat at Dien Bien Phu was yet to come, the Viet Minh were increasingly confident of victory. Such a victory would render Sihanouk’s position untenable and he could well look forward to a life in exile should the Issaraks come to power in Cambodia.

Shortly after his visit to Paris, Sihanouk spoke frankly to the press in New York. He called for immediate independence, warning astutely that if it were not granted his country could turn communist. He repeated his claims in Montreal and arrived back in mid-May to a tumultuous welcome in Phnom Penh. Three weeks later, the portly king was off again, travelling to Siem Reap under the protection of an ex-Issarak ruffian called Puth Chhay. It was as if a US president had suddenly sworn in Al Capone’s mobsters as bodyguards and gone on tour in Nebraska or Oregon. From Siem Reap, he crossed over the border to Bangkok, causing French officials to speculate that he had gone mad. He later crossed back to Cambodia and announced that he would stay in Battambang until the French agreed to grant full independence. In the meantime, his supporters staged huge demonstrations and Sihanouk spoke frequently on radio, his high-pitched voice full of indignation, exhorting his people to keep up the pressure. On 17 August, the French agreed to grant Cambodia full sovereignty and Sihanouk returned to a rapturous welcome in Phnom Penh. Finally, on 9 November 1953, the last French troops left Cambodia, marking the end of 90 years of colonial rule. Sihanouk, in a brilliant display of political theatre, had achieved independence months before the French capitulation at Dien Bien Phu and almost one year before the final declaration of the Geneva Peace Conference on 21 July 1954 brought independence to the whole of French Indochina. He was now the undisputed master of Cambodia.