6

SIHANOUK,

STAR OF THE

CAMBODIAN

STAGE,

1953–70

Ronald Reagan, the Hollywood actor-turned-politician, sometimes appeared to confuse real life with the silver screen, in one instance talking at Omaha Beach in Normandy as if he had actually taken part in the D-day landings. Norodom Sihanouk, too, was also both a political actor and a film star. He wrote, directed and starred in his own productions and conscripted Nhiek Tioulong and other members of the Cambodian political elite as actors, sometimes to play roles similar to those in their real lives. Arguably, Sihanouk ‘wrote’ his kingdom as a vast political screenplay in which he strutted in the starring role among supporting players and hordes of extras before the vast audience of the people. In 1970, the other major players would tire of the screenplay, remove the star and rewrite the script, but for over a decade, from the triumph of the Royal Crusade for Independence until the mid to late 1960s, when his grip on power began to falter, his courtiers performed to order.

Sihanouk was only 30 years old when he led his country to independence. Yet his quick intelligence and driving ambition compensated for his comparative youth, and he was able to shape a political system in which he held almost absolute power. This power derived in part from the respect afforded traditional Cambodian kingship and the monarchy as a whole, but Sihanouk added elements from modernity, and moulded the whole by force of his charismatic personality. Although often lampooned in the US media as a saxophone-playing dilettante and buffoon, Sihanouk was a complex and astute man, capable of extraordinary bursts of hard work. He could be cruel and unforgiving, and he was often arbitrary, but he nevertheless had some real achievements to his name: in Milton Osborne’s words, he was both ‘Prince of Light and Prince of Darkness’.

Sihanouk’s least attractive trait was his craving for power; even before his Royal Crusade, he had acquired the taste for it. The shy and startled youngster who had reluctantly accepted the crown after Monivong’s death in 1941 had metamorphosed into a confident and forceful adult. The 1951 coup against Huy Kanthoul’s government had thrown his Democratic rivals into disarray, and he had neutralised the Issarak guerrilla chieftains by force or guile. He tolerated no rivals, recognised no equals and branded political opponents as traitors. Democracy and pluralism had no place in his script and although some who lived through ‘Sihanoukism’ look back upon it wistfully as a time of comparative prosperity and peace, others remember it as a time of dark shadows presaging future disaster. In truth, it was both. Sihanouk’s greatest achievement was his commitment to neutrality, which kept his country out of the Second Indochina War until 1970. In the end, however, this achievement was undermined by his domestic policies and the country plunged into the abyss of the Second Indochina War and Pol Pot’s bloody revolution.

An ant under the feet of fighting elephants

Sihanouk was confronted with two challenges after the success of his Royal Crusade for Independence. Firstly, as a would-be absolute ruler, he had to consolidate his grip on domestic power, and secondly, he had to maintain Cambodia’s sovereignty in the uncertain world of the Cold War. The two challenges were interlinked and would remain so. Should he falter in the latter task, his domestic enemies would pounce; should he stumble in the former, he would give the cold warriors the opportunity to intervene internally. The best guarantee of peace and territorial integrity, he reasoned, was the adoption of strict neutrality. It would also strengthen his grip on power at home, by siphoning off support from the centre-left Democrats and the pro-communist Pracheachon (People’s Group), both of which preached neutrality to a responsive electorate.

At the time, world politics was dominated by the two postwar superpowers, the United States and the USSR, both of whom controlled informal global ‘empires’ or blocs of allies and satellites. Although many of the emerging post-colonial states of Africa and Asia stood outside of these two blocs, the pressure on them to join one or the other was enormous. In a number of locations around the world, the superpowers or their proxies eyeballed one another across heavily fortified frontiers. Indochina was one of these flashpoints. What had begun as an anti-colonial war of liberation led by the Viet Minh had been transmogrified into a confrontation between communism and the ‘Free World’, with the French colonial army largely bankrolled by the US and the Viet Minh aided by ‘Red China’ and the USSR. In 1953, large tracts of the Cambodian countryside were still controlled by the Khmer People’s Liberation Army (KPLA) and their Viet Minh allies. Cambodia was a small country with insignificant military forces, lying close to the ideological and military fault lines that divided the world. Sihanouk summed up the situation by likening Cambodia to an ant unfortunate enough to be under the feet of two fighting elephants.

Sihanouk’s first task, as he saw it, was to persuade the elephants to do their fighting elsewhere, while trying to remain friends with both. He feared the Viet Minh, but was careful to insist that ‘Although we are not communists we have no quarrel with communism as long as it does not seek to impose itself on us by force . . .’. Likewise, he was fearful of the anti-communist zeal of the United States, and with good reason: this was the time when US Vice-President Richard Nixon was openly canvassing the idea of using tactical atomic weapons to prevent a Viet Minh victory over the French in Indochina. Although the Viet Minh would soon win a stunning victory at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu and hasten French withdrawal, this was still some months off and Sihanouk had every reason to fear that his country would become embroiled in the war.

Sihanouk’s foreign policy was never ideological in the Cold War sense. His imperatives were always pragmatic and he would seek friends where he found them, regardless of their ideological complexion. Initially, he had sought an alliance with the French, but their deviousness in the lead-up to Cambodia’s independence and their revealed military weakness in the face of the Viet Minh made him reconsider. Lining up with a declining colonial power would put him offside with the Viet Minh and their allies, and the newly independent states in Africa and Asia. The United States was another potential ally and had been supplying Cambodia with military and some economic aid since 1951. Sihanouk, however, was mistrustful of the ideological bellicosity of Truman and Eisenhower and their determination to use small countries as pawns in the global battle against communism. These two US leaders saw Southeast Asia, and Indochina in particular, as a cockpit in this battle, and whereas President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had wanted the French out of Indochina, his successors saw them as a bulwark against the spread of the ‘Red Peril’. Sihanouk was fearful, too, of the emerging anti-communist regime in Saigon, seeing it as the descendent of the Vietnamese invaders who had almost absorbed his country during the Cambodian Dark Ages. As the foreign relations expert Roger Smith has noted, Sihanouk’s imperatives were to prevent any return to colonial or quasi-colonial status and to preserve the integrity of his borders. If he sided with either of the two Cold War antagonists or their proxies, he could end up losing some or all of his territory. Siding with either side would guarantee the hostility of the other bloc. Maintaining his distance from both might even lead them to compete for his favour.

It was both a bold and a cautious strategy, for in early 1954 the eventual outcome of the war in Vietnam was unclear. The French armies were demoralised and public opinion at home had swung sharply in favour of withdrawal, but it looked as if the United States might step in to replace France. President Dwight Eisenhower was determined to cobble together a ‘coalition of the willing’ against the Viet Minh, or even to launch unilateral military action to destroy them. In the event, Eisenhower was unable to get support for his plans from the American public (which was war-weary as a result of the gruelling conflict in Korea) or from Congress, and his close allies were reluctant to get involved, so he opted for the negotiating table at Geneva.

Geneva and Cambodian sovereignty

The Geneva Conference opened on 8 May 1954 with delegations from the United States, France, Britain, the USSR, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Cambodia, Laos, the (communist) Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), and its anti-communist rival from the South, the Republic of Vietnam (RVN). The main item of business was to negotiate settlements of the Vietnamese and Korean conflicts. Cambodia was a tangential issue in a conference dominated by the superpowers and their big power allies, but the Cambodian delegates Nong Kimny, Sam Sary and Tep Phan, instructed by Sihanouk, left their modest mark on history. Very quickly, they were on their feet objecting to a proposal from the DRV’s Pham Van Dong (backed by the PRC and the USSR) to seat representatives of the communist-dominated ‘resistance movements’ from Laos and Cambodia (including the Khmer People’s Liberation Army). When it became clear that the issue was a sticking point for Sihanouk’s delegates, the PRC’s Zhou Enlai and the USSR’s Molotov persuaded Pham Van Dong to drop the demand—an early victory for the Khmer delegates.

By mid-July, the delegates had come to an agreement on most issues relating to Indochina.4 However, Sihanouk was unhappy with the final proposals, for although they guaranteed his country’s neutrality they fell short of ensuring the complete withdrawal of the Viet Minh and disarming the KPLA, and also forbade Cambodia from entering into military alliances with other countries. After weary late-night debates, the Russian and Chinese delegates pressured the Vietnamese communists to bow to Cambodia’s terms and Cambodia signed the final agreement on 21 July 1954. It was a significant triumph for Sihanouk’s delegates, who had fought stubbornly for their country’s sovereign rights.

Cambodia’s neutrality was reinforced shortly afterwards when Sihanouk came to an understanding with the PRC and the DRV, both of which guaranteed to respect Khmer sovereignty in return for Sihanouk’s promise that no US military bases would be set up on Cambodian soil. The agreement displeased the US, which initially threatened to withhold all aid from Sihanouk’s regime. Sihanouk did not back down and after 1955 Washington changed tack and promised large amounts of military assistance and also pledged its support for Cambodian neutrality and sovereignty. In the same year, Sihanouk attended the Bandung Conference of non-aligned nations, where he met with such luminaries as Jawaharlal Nehru, Ahmed Sukarno and Josip Tito, and was lionised as a leader of the anti-colonial struggle of Third World people. The communist bloc countries also began to provide Cambodia with economic aid on more favourable terms than those of the Americans and other capitalist countries (although US aid was consistently larger than that of all of the other donors combined).

Sihanouk consolidates power

Sihanouk had come to sovereign power in 1953 with a fund of political goodwill. His achievements on the international stage enhanced his prestige among his subjects and undercut the Democrats and the procommunist Pracheachon. He had steered his country to independence and tacked skilfully to ensure that it would be maintained on course in the face of gale force international winds. He was also a Khmer king and could expect fealty from his loyal subjects; for him, they were children and he was the father who knew what was best for them, and this was the script he would follow on the Cambodian stage. In the immediate postwar years, Sihanouk had initially flirted with the ideas of constitutional monarchy, but in 1951, when he used French tanks and infantry to close down the Huy Kanthoul government, he set off down an authoritarian path. He was not to deviate from this until his removal from power in the coup of March 1970.

Nevertheless, Sihanouk still faced considerable domestic opposition in the first years of the independent kingdom. The Democrats still enjoyed strong residual support and Sihanouk was fearful that his archrival Son Ngoc Thanh might attempt a comeback into the political mainstream. Son Ngoc Thanh remained a symbol of nationalism for the many Cambodians who could remember his role during World War II, and if anyone could challenge Sihanouk, it was this bespectacled ascetic from the lower Mekong delta. Whenever Son Ngoc Thanh had returned to Cambodia from exile, enormous crowds had flocked to welcome him back. Although he was now in the jungles with the remaining Issaraks, he was negotiating for an amnesty. Sihanouk had to move quickly.

Abdication and the Sangkum

Accordingly, in a typically audacious, but astute move in early March 1955, Sihanouk suddenly abdicated in favour of his father, Prince Suramarit. Sihanouk reasoned that Suramarit would not use his regal powers to undermine his favourite son in the political arena. This would give Sihanouk a free hand in politics. The move also preserved the monarchy, which Sihanouk believed to be the social cement of the nation. Sihanouk’s second (and linked) move was to create his own political movement. He did so in part because he was disgusted with the horse-trading and graft of the existing parties and was determined to create a grand alliance that would put the interests of the country, as he saw them, before self-interest and petty bickering. The Ministry of Information estimated that around a dozen parties existed in Cambodia in 1955 and noted that many of them were ‘without defined programmes’ and served as vehicles for the personal ambitions of their leaders. While this was largely true, Sihanouk’s underlying motive was to entrench his own power. He instinctively distrusted the party system as a mechanism for diluting that power, and worried that it might elevate his rival Son Ngoc Thanh to high office.

Sihanouk also had to contend with pressure from the party politicians for fresh elections. Sihanouk, realising that elections conferred legitimacy on those who won them, was not opposed to ballots, but he wanted to make sure that his power would be enhanced, not challenged by them. He prepared the ground by bringing the motley collection of parties under his direct control. Characteristically, he did this via a referendum, in which 99.8 per cent of the voters approved the merger of parties into a grand ‘movement of national union’, which he dubbed the Sangkum Reastr Niyum, or Popular Socialist Community. This corporatist movement was to be the political umbrella for the whole nation and Cambodia became a de facto one-party state in which civil servants were expected to join the Sangkum. When the elections were held in September 1955, only two opposition parties remained outside of the Sangkum fold: the Left-leaning Democrats, whose existence dated from 1945, and the Pracheachon, the party which the communists had founded in 1951 as part of their two-track ‘ballot box and bayonet’ strategy. Another independent party, the Liberals, had collapsed in disarray when Sihanouk offered its leader, Prince Norindeth, a diplomatic post at UNESCO in Paris, with the proviso that he join the Sangkum.

Meanwhile, Sihanouk’s diplomatic triumphs ensured him of continuing high levels of support. In late April he had returned from the non-aligned conference at Bandung, with the endorsement of the world’s anti-colonial leaders. The following month, he signed an agreement providing for continuing US military aid, a move that soothed fears about his country’s ability to defend itself, particularly among right-wingers who feared North Vietnam and China.

The 1955 elections

The elections for the National Assembly were held on 11 September 1955. Observers had expected a large vote for the Democrats and a smaller, but still respectable tally for the Pracheachon (with the outside possibility of these parties governing in coalition). The result, however, was a landslide for the Sangkum, which secured 82 per cent of the National Assembly seats, as opposed to the Democrats’ 12 and the Pracheachon’s 4 per cent. Sihanouk had loaded the dice: although the odds were that the Sangkum would have won anyway, he left nothing to chance. Voters were required to throw away the voting slips of the candidates they did not favour. This automatically favoured the Sangkum, as Sihanouk’s face appeared on their ballot slips and it was a punishable offence to show disrespect by discarding anything carrying his image.

The flavour of these elections can be gauged by the fact that Sihanouk had appointed the brutally unsavoury Dap Chhuon—the governor of the north-western provinces—as ‘director of national security’ to oversee the process. On polling day, voters were harassed by Sangkum thugs and police. Moreover, in the weeks leading up to the elections, a number of opposition newspapers had been closed down and their editors detained without trial—a tactic that Sihanouk had earlier employed against dissidents during the 1951 coup. Opposition campaigners had to be physically brave. The Democrat leader Keng Vannsak, a prominent left-leaning intellectual at the time, was bashed and his chauffeur killed, while a prominent Buddhist monk, the Achar Chung, died in jail after publicly reciting poems deemed disrespectful to Sihanouk.

The election was to set the country’s political tone for the next decade and a half. Sihanouk was determined to run the country as he saw fit, relying only on an inner circle of courtiers, including Prince Monireth and his nephew Sirik Matak, along with elite commoners such as Penn Nouth, Son Sann, Sim Var, Yem Sambaur, Nhiek Tioulong, Sam Sary and Lon Nol. These men sprang from a narrow ruling class tightly bound together by ties of kinship and shared interests. Although Sihanouk was not averse to making demagogic verbal attacks on this elite, and claimed his Sangkum movement was socialist, these were populist ploys to disguise his support for the status quo.

In its more honest moments, the Sangkum media justified structural inequality as the workings of karma: the poor were poor because of the bad things they had done in previous lives, while the rich and powerful enjoyed the fruits of their virtue. As David Chandler has observed, independence meant that for the overwhelming majority of Khmers life went on as before with a new set of rulers and they ‘continued to pay taxes to finance an indifferent government in Phnom Penh (or Udong or Angkor) . . .’. Cambodia had undergone a political revolution, but Sihanouk suppressed any chance of social change while cultivating the people with demagogic verbal assaults on the rich. This royal populist also made a great show of going to the people, sometimes stripping to the waist to make one or two desultory blows with shovel or mattock on a new public works project. It was cheap theatre, but it worked.

‘Totalitarian democracy’

The new political system took some fine-tuning. The Sangkum was an unwieldy instrument because the amalgamation of the old parties did not end the old personal rivalries or intrigues of the corrupt cabals. In addition, many of its candidates were poor human material, dullards, grafters and time-servers unlikely to incline towards independent political thought or action. The 1955 election triumph was followed by a series of cabinet crises and resignations. But even this was grist to Sihanouk’s mill, enabling him to pick and choose his men and play off rivals against one another. And if he chose, he could always have recourse to what became a favourite ploy: threatening to resign only to be ‘persuaded’ by stage-managed demonstrations to change his mind.

The 1955 election victory was followed by an even more dizzy success in 1958, when Sihanouk’s personally handpicked Sangkum candidates won 99 per cent of the votes cast. The vast size of this majority casts doubt on its legitimacy and mirrored the state-orchestrated electoral charades of the Stalinist countries, with their party slates, police surveillance and licensed ‘oppositions’. To adapt Henry Ford’s words about the one choice of colour for his eponymous T-model car: in the 1958 elections you could vote for whomever you wanted, as long as they were part of the Sangkum. Opposition candidates were terrorised into withdrawing from the lists and a single courageous candidate from the Pracheachon scored less than 500 votes. It should be pointed out, however, that over 55 per cent of eligible voters in Phnom Penh failed to vote, whether from fear, disgust, apathy or a combination of motives. The deposed former prime minister, Huy Kanthoul, greatly overstates his case when he claims that by 1955 Sihanouk was ‘thoroughly hated, particularly by young people’, but there is no doubt that Sihanouk was slowly squandering his fund of goodwill, especially among town-dwellers and those with some education. Meanwhile, Cambodia had drifted close to what Jacob Talmon has elsewhere described as ‘totalitarian democracy’—that is, dictatorship under the façade of mass participation in the political system.

Pressure from the United States and its proxies

The main potential for destabilisation of this system came from without. The 1954 Geneva Conference had resulted in a truce between the combatants in Vietnam and had guaranteed Cambodia’s sovereignty, at least in the short term. But it was not to prove the lasting settlement that its more optimistic participants had hoped for. The five years after Geneva illustrate Thomas Hobbes’ melancholy dictum that peace is only ‘recuperation from one war and preparation for the next’, with both sides arming for a resumption of the fray. In 1955–56, after France’s ignominious exit from Indochina, over 60 per cent of all US foreign aid flowed to Southeast Asia, the overwhelming bulk of it military. Sihanouk had persuaded the ‘elephants’ not to fight near his nest and had, moreover, succeeded in extracting considerable amounts of help from them, playing one off against the other to extract the most favourable terms.

But the US was unhappy with Cambodian neutrality, which it believed was a weak point in a cordon sanitaire against the communist ‘virus’. For the next 15 years US policy was to cajole, bluff, bribe or bully Cambodia into the Free World as a front-line state in the war against communism. Generally, the US brought pressure to bear indirectly on Cambodia via its Southeast Asian satellites and SEATO partners, the Philippines, the Republic of Vietnam and Thailand in particular. Thus, when Sihanouk made an official visit to the Philippines in early 1956, the Manila press speculated that Cambodia was about to drop its non-aligned status and seek rapprochement with the Free World. Apparently unfazed, Sihanouk reiterated his country’s neutrality and cheekily announced that he had accepted an official invitation to visit Beijing.

Thereafter, Cambodia’s relations with its anti-communist neighbours—and traditional enemies—in Bangkok and Saigon deteriorated. Cambodia complained of continual border incursions from Thailand by right-wing, pro-US Khmer Serei (Free Khmer) guerrillas linked to Son Ngoc Thanh and there were reports of similar harassment over the frontier from southern Vietnam. These neighbouring countries also imposed an economic blockade on Cambodia and in November 1958 Sihanouk broke off diplomatic relations with Thailand, restoring them after US mediation in February of the following year, only to break them again in 1961. Another running sore was the issue of Preah Vihar, an Angkorean temple on the border that was claimed by both Thailand and Cambodia (and eventually awarded to Cambodia by the World Court at The Hague in 1962). While the hardline anti-communist rulers in Bangkok and Saigon scarcely needed encouragement, Sihanouk suspected with good reason that the United States was egging them on and said that if Washington chose it could call them off. He stated publicly that US policy was unjust and ‘dangerous for peace in Southeast Asia’ and moved further towards diplomatic rapprochement with the communist countries. In July 1958, some 13 years before the UN and the United States took a similar step, Sihanouk gave de jure recognition to the PRC and two years later signed a treaty of friendship with Beijing. Anti-communist zealots in Washington, Saigon and Bangkok seethed with rage.

Pro-US plots against Sihanouk and neutrality

The overseas anti-communist chorus also struck chords in the hearts of some of Sihanouk’s conservative courtiers. In 1958, Sam Sary, a longtime Sihanoukist minister and diplomat, suddenly informed Sihanouk that he wanted to set up an opposition political party, and published an independent right-wing newspaper, the Democratic People, which attacked Cambodia’s ties with China. Sam Sary had recently been sacked from his position as ambassador in London following a scandal involving his mistress, and it seems likely that he had come under the influence of US intelligence. Observers noted that his political schemes had ‘no visible means of support’. After Sihanouk denounced Sam’s party as a plot cooked up by the Americans to undermine neutrality, the former diplomat fled to join Son Ngoc Thanh in Bangkok. The two exiles were not close and Sam Sary vanished a few years later, perhaps murdered, as David Chandler suggests, by one of his foreign backers.

The pro-US intrigues continued into 1959. In February, Sihanouk accused General Dap Chhuon, the governor of the north-west provinces of Cambodia, of plotting to overthrow him. Sihanouk alleged that the general had been bribed to support the installation in Phnom Penh of a pro-American government led by Son Ngoc Thanh. The evidence shows that the conspiracy was hatched by the Diem regime in Saigon, with support from Thailand and a CIA agent called Victor Matsui. The hapless Dap Chhuon was ‘shot while attempting to escape’ on the orders of Sihanouk’s police chief, Colonel Lon Nol, a sinister character who had begun a career of murdering political opponents as far back as 1945. Six months later, a bomb exploded at the royal palace in Phnom Penh, killing the palace chief of protocol, Prince Vakrivan, along with King Suramarit’s personal valet and injuring a number of other personnel. Sihanouk blamed Sam Sary and Son Ngoc Thanh and claimed that the bomb had been sent from a US military base in South Vietnam, wrapped as a gift.

While the Dap Chhuon and Sam Sary affairs did not present a real threat to Sihanouk’s power, they heralded a much wider political disgruntlement that was to lead to his downfall in 1970 at the hands of other pro-US rightists. In the meantime, however, Sihanouk put the neutrality issue to a referendum and 99 per cent of voters endorsed his policy. While there were irregularities in the ballot, there can be little doubt that the pro-US stance of the plotters was deeply unpopular and that neutrality was accepted across the spectrum of political opinion. After the resumption of hostilities in southern Vietnam in 1959, few could doubt its wisdom.

The constitutional crisis of 1960

The system was plunged into sudden crisis, however, by the unexpected death of Sihanouk’s father, King Suramarit, in early April 1960. Although grief-stricken, Sihanouk had to act decisively to keep the system together. His dilemma was to ensure that he kept all power in his own hands, while simultaneously maintaining the monarchy, which he believed to be the social glue that bound together the nation and the political regime he had constructed. His father had been a loyal supporting actor, never wishing to challenge his son’s hold on power yet playing an essential role in the political script. There were any number of potential candidates for the throne, but Sihanouk was fearful of successors who might wish to wield real power. Sihanouk could not risk crowning a prince who might wish to be more than a figurehead. Nor did a republic appeal: Sihanouk was afraid that abolishing the monarchy would allow his archrival Son Ngoc Thanh to challenge him on new political terrain. Moreover, a republic would destabilise Cambodian society.

The logical choice for Suramarit’s successor was Prince Raniriddh, Sihanouk’s oldest son, but he was not yet of age and Sihanouk—perhaps forgetting his own frivolous youth—dismissed him as a lightweight more interested in fast cars and being rude to the police than in serious matters of state. Theoretically, there were around 100 other princes from whom to choose, but many of them were hopelessly corrupt, incompetent or debauched. Others craved power and the royal family was still driven by personal and dynastic intrigues, including the squabble between the Sisowath and Norodom wings. Although he did not say it publicly, neither did Sihanouk want his mother, the strong-minded Queen Kossamak, or his uncle, the stern disciplinarian Prince Sisowath Monireth, to ascend the throne as both might seek to meddle in affairs of state. Sihanouk’s solution to the constitutional crisis was typically bold: he would become head of state (but not king) and Monireth would become chairman of a regency council (but not regent). Sihanouk would retain all power and monarchy would continue as the social and political glue of the kingdom.

Two months after the crisis had begun, Sihanouk let himself be ‘persuaded’ by demonstrators to become head of state, with Monireth as chairman of the ambiguous council. A day earlier, the National Assembly had voted to revise the country’s constitution to allow for a regency of indefinite duration. Again, Sihanouk had written the script and he played the starring role beautifully for the opportunists and the unsophisticated who made up the bulk of his supporters. He had turned the crisis to his advantage and could now present himself as the indispensable father of the nation. The regency council simply faded from view.

Circuses in the style of Vichy

The modified regency had been Sihanouk’s private decision, but significantly he had first broached it publicly at a mass assembly on Men Ground, adjacent to the royal palace in Phnom Penh. Going directly to the people over the heads of his courtiers was a staple of the Sihanoukist system. It was a technique he had honed in the year before the 1958 election (although he was originally influenced by the mass pageantry of the Vichy period when he had proudly reviewed the fascist-saluting ranks of adoring Yuvan). Such spectacles made for exciting political drama, indulged his ego and appealed to his instinctive belief that politics could be reduced to an aesthetic experience.

Now he adapted the style of Vichy to his own state. In September 1957, Sihanouk summoned five prominent leaders of the Democratic Party to a stage-managed ‘debate’ on Men Ground before a huge and murmurous crowd. The victims sat silent and dejected as Sihanouk harangued and insulted them in a marathon diatribe in his high-pitched voice. They recanted their ‘heretical’ views and as they slunk from the arena soldiers and members of the crowd physically assaulted them. It was coarse theatre, with overtones of a Maoist struggle session against ‘revisionists’.

Such bullying highlighted Sihanouk’s increasing narcissism, which went hand in hand with a deep streak of cruelty in his nature: for the Prince and crowd alike, it was a blood sport. Yet it served its purpose: the immediate outcome was the final dissolution of the Democrats, and Sihanouk was so delighted that from then on the assemblies on Men Ground were held twice a year and given a place in the country’s constitution. With a cast of tens of thousands, these assemblies gave the ‘extras’ a sense of belonging and the illusion of popular power, and served as a safety valve for pent-up passions, while entrenching real authority firmly in the hands of the excitable little star. The Pracheachon suffered the same fate in the lead-up to the 1962 elections, with party leader Non Suon humiliated before an irate crowd, although he was spared a beating.

The large royal socialist youth movement, which boasted over half a million members by the early 1960s, also had its model in the Yuvan of the Vichy period. Again, it brought young people out of their families and villages, gave them a new sense of identity and bound them closely to the Sihanoukist state. Its members worked on public works projects, paraded the streets and participated in scouting activities that instilled them with a spirit of patriotism and loyalty to Sihanouk. The unashamedly paramilitary style of the organisation was antipathetic to democratic notions. Decisions were made at the top and orders were to be obeyed—a paradigm for Sihanoukist society as a whole. Yet the mass appeal of this movement and the other populist spectacles masked long term structural weaknesses within the system.

The flaws of Sihanoukism

All dictatorships eventually crumble, and Cambodia was no different. Sihanouk probably imagined that his system was the best in ‘the best of all possible worlds’ and could last indefinitely. Yet it was fraught with contradictions that would eventually lead to his political downfall. The Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen argues that the needs of a developing country are best served by a democratic system with a healthy civil society. If the Right to speak out and organise for alternative platforms are denied, he contends, there is little chance of the errors of the rulers being corrected. Cambodia was a case in point. Sihanouk’s ‘ruling style’, as David Chandler has observed, was ‘totalitarian and absurd’ and had the effect of ‘closing off any possibility of pluralism, political maturity, sound planning, or rational debate’.

Authoritarian regimes lack accountability and checks and balances, and encourage corruption, incompetence and plain wrong-headed policies. The civil service should be free to give objective advice to governments, but the Sihanoukist system encouraged obsequiousness, incompetence, corruption and opportunism. Sycophants were rewarded for telling their master what they believed he wished to hear, whereas honest officials and ministers were punished for speaking the truth. One suspects it was the honesty and independence of mind of the leftist ministers Hou Yuon, Hu Nim and Khieu Samphan as much as their ideology that caused Sihanouk to turn angrily against them in 1962. It was also farcical to suggest that Sihanouk had cleaned up corruption, for the Sihanoukist state was riddled with graft. This was exposed in the Labat Affair of 1960, which contributed to the resignation of the government of the day. M. Labat was an old French colonial civil servant who had stayed on after independence. When he died in early 1960 it was revealed that he had looted the equivalent of US$2 million from the public purse and that his peculations were not an isolated aberration.

Sihanouk’s positive achievements

Sihanouk did have some real achievements to his name. He was not ‘Snookie’, the authoritarian buffoon that Time and Life sneered at during the 1960s, but he was a deeply flawed and fallible man, blinded to reality by his huge ego and sense of destiny. Some of his domestic programs were creditable. Compared to the cheeseparing French colonial administration, Sihanouk’s Cambodia spent heavily on education and health. Education typically absorbed around 20 per cent of the budget throughout this period, compared with a mere six per cent in 1930, a fairly typical year under the French. Sihanouk expanded Cambodia’s primary and secondary education system, and set up the country’s tertiary system almost from scratch. He was quite correct in his belief that education was the key to modernisation. The trouble for the regime was that employment opportunities failed to keep pace with the stream of secondary and tertiary graduates, and this created disaffection among educated urban youth, which was to have important political repercussions. Charles Meyer, the Frenchman who served as Sihanouk’s aide during this period, is also rightly critical of the exaggerated claims that an educational revolution had occurred under Sihanouk. Much of it was ‘smoke and mirrors’ designed to boost Sihanouk’s power and glory, yet it was still an improvement on what the French had managed throughout their 90 years in the country.

The French also had scarcely developed any industry in Cambodia, and although the country’s main exports by the mid-1960s were still from the primary sector (including rice, fish and fish products, livestock, rubber, maize, pepper, cardamom, sugar, soy beans, tobacco, cotton and coffee) the country had built up a number of secondary industries since independence. These included a major cement plant, jute, textile and cotton mills, sawmills and paper and plywood factories and, towards the end of the Sihanouk period, an oil refinery at Kompong Som. According to the French economist Rémy Prud’homme, the number of industrial enterprises grew from just over 1100 in 1956 to just under 2700 in 1965. The government had also sought to develop the country via a series of national plans, including a two-year plan in 1957–58 and a five-year plan between 1960 and 1965, and had opened a blue-water port at Kompong Som (Sihanoukville) on the Gulf of Thailand in 1960. The new port was linked to the capital by an American-built all-weather road and later by a railway line, thus easing the country’s dependence on shipping up the Mekong via the hostile Republic of Vietnam. Although still an overwhelmingly rural society, Cambodia’s towns and cities expanded rapidly; Phnom Penh’s population doubled in the ten years after 1956 to around 600 000. The 1968 Shell Guide to Cambodia described Cambodia as ‘a modern, forward-looking state with fast-developing industries, excellent communications, and first-rate hotel and touring facilities’ with ‘up-to-date modern buildings . . . wide boulevards, and [a] modern way of life in the cities . . .’. This is exaggerated, and was co-written by Sihanouk’s Ministry of Information, but it is nevertheless true that the prince had done more to modernise his country than the French protectorate had ever done.

The system begins to unravel

Beneath the propaganda, however, all was not well in the kingdom. Although Dap Chhuon was a chronic turncoat, the defection of the insider Sam Sary to the Khmer Serei in 1958 was symptomatic of a more serious malaise within the Cambodian political system. In the following years, dissatisfaction mounted on both Left and Right with the way Sihanouk ran the country. The suppression of the party system had not ended corruption; in fact, as the Labat Affair demonstrated, it had grown worse. Even the expansion of the education system had an important downside for the regime. It had produced the largest numbers of secondary and tertiary educated Khmers in the country’s history, and many of them considered themselves intellectuals. Unfortunately, there were few jobs for this growing pool of comparatively well-educated youth, at least not in the type of employment to which they felt entitled. These volatile young people were to turn against the regime they felt had failed them, some siding with the extreme right and others with the extreme left. Many of those educated overseas returned with ‘subversive ideas’: Sihanouk claimed that 35 per cent of returning graduates from French universities were ‘infected’ with communist beliefs. Sihanoukism relied on the gullibility of the people, whereas education allowed them to think critically and formulate alternatives.

The first inkling of the depth of opposition to the government among young people came in February 1963, when students rioted in Siem Reap to protest against local incidents of police brutality and corruption. Significantly, the students also smashed portraits of Sihanouk and denounced the Sangkum, showing that they viewed the local problems as symptoms of a systemic malaise. Following student solidarity demonstrations in Phnom Penh and Battambang, the government of the day resigned. Sihanouk and his courtiers blamed both the extreme right and left for the disturbances: a convenient method to cover up the deeper causes of discontent.

Terror against the Left

These destabilising pressures were boosted after 1959, when the Vietnamese communists launched armed struggle against the Saigon regime. The war was soon lapping at Cambodia’s borders, and in January 1962 the first US bombs fell on the east of Cambodia, the precursor to what would become one of the heaviest aerial bombardments in history. Sihanouk was suspicious of the loyalties of the Cambodian communists: were they with their insurgent Vietnamese comrades, or with Cambodia, which he identified with himself? Were they neutral or would they attempt to extend the conflict into a wider ‘war of national liberation’ involving Cambodia? Many of the older generation of communists from the Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party (KPRP) had retreated to Hanoi after the 1954 Geneva Accords and Sihanouk feared that they would return to act as a pro-Vietnamese fifth column inside Cambodia. In addition, a new generation of leaders was rising through the party’s ranks, and disaffected young people were attracted to an organisation that promised honesty and justice and which, never having enjoyed power, had clean hands. A secret conference in September 1960 at the Phnom Penh railway station signified a new militancy among Cambodian communists. The new party leaders included a comparatively young man called Saloth Sar, a former student in Paris who earned his living as a teacher in Phnom Penh. He would later become known to the world under his nom de guerre of Pol Pot.

In 1962, Sihanouk decided that the time had come to crush these insolent Khmers Rouges (Red Khmers), as he dubbed them. Party general secretary Tou Samouth, a veteran of the Issarak struggle against the French, disappeared and although the Australian historian Ben Kiernan speculated that he had been murdered on Pol Pot’s orders as part of a factional struggle within the party, newer evidence suggests he was assassinated by Sihanouk’s police and thrown into the Mekong. The government staged a purge against the legal, pro-communist Pracheachon, rounding up thousands of real and alleged members and sympathisers on trumped up charges of treason. Many were sentenced to death by kangaroo courts, although the sentences were all commuted to long terms of imprisonment. By this stage, the Vietnamese communists had established bases in the mountainous jungles along the border with Cambodia, and as the dragnet intensified many Cambodian communists quietly slipped away to join them, convinced that their lives were in danger. Some leftists such as Khieu Samphan, Hu Nim and Hou Yuon, who had been co-opted into the Sangkum, were stripped of their offices and titles, but stayed on in the capital, where they enjoyed a certain popularity as honest men in a den of thieves. In the 1966 elections, these three leftists won increased majorities against the ‘official’ candidates.

Sihanouk’s left turn

Paradoxically, while he attacked the Cambodian communists, Sihanouk steered his domestic and foreign policies sharply to the Left. In January 1963, the government nationalised Cambodia’s banking and foreign trade and embarked on a program of setting up state-owned industries: policies that had been originally proposed by Hou Yuon and the other leftists sacked from ministerial positions the previous year. On 1 May 1963, an auspicious date in the communist calendar, the Chinese President Liu Shaoqi arrived in Cambodia and shortly afterwards the two countries signed a treaty of friendship. Three months later, Sihanouk broke off diplomatic relations with the Saigon regime in protest at border violations and mistreatment of the Khmer Krom minority in the lower Mekong delta, and in November of the same year he abruptly cut off all US military and economic aid.

Although China increased its economic assistance package shortly afterwards, this could not compensate for the loss of US aid. Since Cambodia’s independence, the United States had contributed almost US$404 million to the Cambodian state, more than double the quantity given by all other donors combined and amounting to a 15 per cent annual subsidy of the Cambodian treasury. The move away from US support might have been good for Sihanouk’s pride, but the sudden drying up of funds was a major trauma for the Cambodian economy and alienated many army officers. Sihanouk’s tactics in repressing the Left while adopting aspects of their economic program might have neutralised the communist ‘peril’ to some degree, but it also had the opposite effect of estranging the more conservative of his supporters. The Sangkum had voted unanimously to endorse the rejection of US aid, but the anticommunist technocrat Son Sann resigned in protest and subsequent events indicate that many conservatives shared his misgivings. Many of Sihanouk’s courtiers would have privately half-agreed with the opinion of the U.S. News and World Report in April 1967, that Cambodia was ‘a country that’s “neutral” in favor of Communists’.

Brewing economic crisis

Nor was the government’s quasi-socialist experiment as successful as Sihanouk had hoped, for incompetent and corrupt management and a shortage of expertise at other levels hamstrung the nationalised industries, and the state monopoly of foreign trade led to a flourishing black market. Whereas the profit motive provided incentives for efficiency on the part of the managers of private firms, nationalisation Sihanoukstyle gave dishonest civil servants new openings to divert state revenues into their own pockets. By the mid-1960s, the country was suffering from the effects of spiralling inflation and decreasing government revenues. One cause of this was the trade in rice and other commodities with the Vietnamese communists in their bases along the Cambodia–South Vietnam border. David Chandler estimates that by 1967, one quarter of total Cambodian rice production was being sold to the Vietnamese communists. While this might have made individual Cambodian entrepreneurs rich, it led to a huge loss of state revenues from export taxes.

By the mid-1960s, Sihanouk’s grasp on power was slipping. The country was suffering an economic crisis, and he had managed to alienate both the Left and Right. The conservatives detested his ‘royal socialism’ and believed his foreign policy was too closely aligned with the communist countries. They were also fearful and angry over Sihanouk’s tolerance of the Vietnamese communist military bases in the east of the country, which they saw as an infringement of Cambodia’s sovereignty and more fancifully as a threat to the Cambodian state itself. In the far north-east provinces of Mondulkiri and Rattanakiri, the communist guerrillas fostered a rebellion of hill peoples against the Phnom Penh government. Increasingly, Cambodian rightists must have wondered if Son Ngoc Thanh and the Khmer Serei were not correct in their calls for an anti-communist alliance with the United States and the Republic of Vietnam. After the United States decided to commit large-scale military forces to Vietnam in 1965, neutrality appeared an even less attractive option. Surely, Cambodian rightists might have reasoned, the Vietnamese communists could not stand up to the awesome firepower unleashed against them by President Johnson.

However, Sihanouk’s foreign policy tilted still harder to the left. Relations with the United States and South Vietnam deteriorated throughout 1964, with mobs stoning the US embassy in Phnom Penh on several occasions, Cambodian border villages attacked by South Vietnamese troops, and US military aircraft shot down by Cambodian anti-aircraft fire. By the end of the year, Sihanouk appeared to have made up his mind to tilt even more strongly against the United States. He accepted MIG fighters and heavy artillery from China and the USSR, and in March 1965, almost simultaneously with the arrival of the first US marine forces in Vietnam, he hosted an Indochina People’s Conference, which condemned US policy in Southeast Asia. The process reached its logical end after US aircraft bombed the Parrot’s Beak salient on his eastern border, giving Sihanouk the pretext to break off diplomatic relations with Washington on 3 May 1965.

The US was unmoved, although it did make some conciliatory overtures via third parties, including the Australian embassy at Phnom Penh. As an internal US government memo to President Johnson pointed out, ‘Cambodia has provided a variety of facilities for the Viet Cong over a long period of time and is therefore in a poor position to criticize a single Air Force error, however tragic it is for those who were hit.’ Six months later, Sihanouk further reinforced his ties with the communist countries with visits to China and North Korea. The United States, for its part, authorised its forces to undertake ‘hot pursuit’ of fleeing Vietnamese communist forces into Cambodia and there were a number of incursions by Khmer Serei guerrillas from both Vietnam and Thailand. In 1967, the US military stepped up its armed incursions into Cambodia with the clandestine Operation Daniel Boone search-and-destroy missions. However, a US intelligence report conceded that Sihanouk had little control over ‘Viet Cong’ operations along the 965-kilometre border with South Vietnam. In other words, by 1967 Cambodia was in precisely the situation that Sihanouk had striven so hard to avoid in 1953–54: it was an ant under the feet of fighting elephants.

Sihanouk was also facing increasing disaffection from the political right inside Cambodia itself. Although the leftists Khieu Samphan, Hu Nim and Hou Yuon kept their seats with increased majorities in the 1966 national assembly elections, the conservatives swept the board and in October, the arch rightist Lon Nol (now promoted to General) was installed as Prime Minister. Sihanouk offered cabinet positions to Khieu Samphan, Hu Nim and Hou Yuon, perhaps hoping that they would act as a counterweight to the growing power and independence of the rightist deputies, but they declined, not wishing to be associated with Lon Nol, the instrument of white terror against the Left.

The peasant uprising at Samlaut

By and large, the peasants had been quiescent during the years since independence and many had retained a deep reverence for Sihanouk. Their role in Sihanouk’s screenplay was as extras to keep the country’s rice bowls full and to supply local colour to government pamphlets

Top:

The King’s palace, Phnom Penh, soon after its construction in the 1870s. (Courtesy Cambodian National Archives, Phnom Penh)

Bottom:

The coronation of King Monivong, 1928. (Courtesy Cambodian National Archives, Phnom Penh)

Top:

At an altitude of over 3000 feet, the Grand Hotel in Bokor was a pleasant hill station for the French. It is now lies in ruin. (Courtesy Cambodian National Archives, Phnom Penh)

Bottom:

The design of Cambodian buffalo carts has not changed since the time of the Angkorean Empire. (Author’s collection)

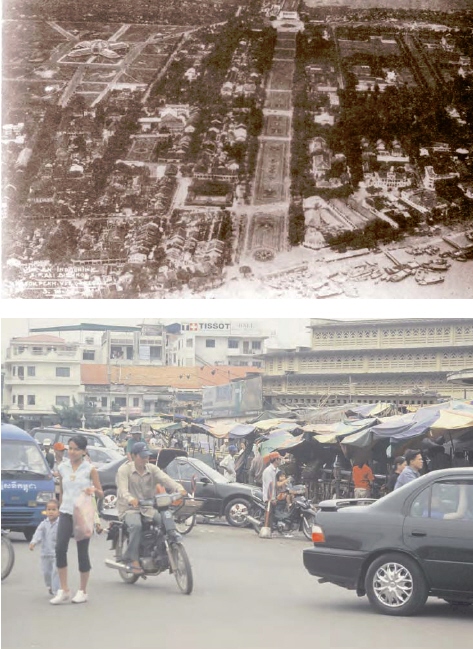

Top:

An aerial view of Phnom Penh in the 1930s. The cruciform building at top left is the art deco central market, the railway station is top centre at the end of a wide boulevard and Tonlé Sap is in the foreground. (Courtesy Monash University)

Bottom:

The art deco design of Phnom Penh’s central market can still be glimpsed above the chaos of this bulging city. (Courtesy Ian Thackeray)

Top:

Built by Jayavarman V (968 to 1001), the architectural detail and carvings at Banteay Srei (Temple of the Women) are some of the finest in Khmer art. (Courtesy Ian Thackeray)

Bottom:

With few industries or natural resources, Cambodia has firmly placed its economic future in the hands of the tourist industry. (Courtesy Ian Thackeray)

and his own films. Their lives were hard, but their religion taught them the virtue of resignation and they seemed passive and docile. However, as King Norodom had warned back in the 19th century, they were like buffaloes—long suffering, yet terrible in their anger when their patience was exhausted. In April 1967, a peasant revolt flared when angry villagers killed police and soldiers and burned down government offices at Samlaut, in the north-west province of Battambang. The soldiers had been sent to requisition rice at low prices set by the government, depriving the peasants of the higher prices paid on the black market, which was controlled by private entrepreneurs who sold the rice to the Vietnamese communists. It is also likely that regionalist feeling was another factor in an area with a history of armed opposition to central governments in Phnom Penh. Sihanouk ordered a cruel repression that dwarfed anything carried out during the French colonial period. General Lon Nol crushed the rebels with bloody zeal, eager to prove his loyalty, as Sihanouk had recently humiliated him for allegedly allowing the Cambodian communists to get out of control. According to Sihanouk’s own offhand estimate, as many as 10 000 peasants were killed and he has never apologised for the overkill. Disaffection spread, with scattered revolts elsewhere in the countryside and students staging demonstrations against the regime’s brutality.

The government sought scapegoats for the Samlaut affair and the most obvious targets, given that most communists had gone to ground or had fled to the jungles of the north-east, were the trio of leftist former ministers who had remained in Phnom Penh and retained their seats in the National Assembly. Shortly after the end of the revolt, and fearing another anti-communist pogrom, Hou Yuon and Khieu Samphan quietly slipped away to join Pol Pot in the jungles, followed later in the year by Hu Nim. The rumour spread that they had been murdered on Sihanouk’s orders and although this was not true, it further undermined the moral standing of the regime. Moreover, with the departure of the men who became known as the Three Ghosts, all hope of the incorporation of a section of the Left in the existing political system disappeared. The following January, the Khmers Rouges, as yet a small guerrilla force, launched an armed offensive against the government from the shelter of the eastern forests. By 1970, they either controlled or made unsafe up to 20 per cent of the countryside.

Sihanouk loses control

Sihanouk, once so self-confident and assured, was losing his grip on domestic politics and his foreign policy was increasingly becoming erratic. In 1968, both the NLF and the DRV opened embassies in Phnom Penh, but later in the year Sihanouk put out feelers via the French Embassy, assuring the United States of his heartfelt desire for reconciliation. As evidence of his newfound goodwill towards the country he had so often vilified, he released a number of US military personnel who had been captured inside Cambodian territory. Sihanouk was well known for dramatic changes of political course and quixotic gestures, but these flip-flops pointed towards his growing powerlessness. He also left an increasing share of the day-to-day running of the country to Prime Minister Lon Nol and his deputy, Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak. Matak, a strongly anti-communist career civil servant, was becoming increasingly alienated by the incompetence and aimlessness of his cousin’s system. Sihanouk had wanted all power, but now he shirked the responsibilities it brought with it and spent much of his time making films.

Sometime during this period, Sirik Matak began to think seriously of deposing Sihanouk and began to stand up against him publicly. In August 1969, he persuaded Lon Nol to refuse to form a new cabinet unless he could choose his own ministers, who would be answerable to him and not Sihanouk. Sihanouk was forced to agree, something that would once have been unthinkable. The little rebellion struck a chord. Many prominent Cambodians were disgusted by Sihanouk’s self-indulgence, highlighted in 1969 when he awarded himself a statuette cast from gold ingots taken from the country’s treasury for winning first prize in a stage-managed film festival. Widespread dislike for Sihanouk’s wife, Monique Izzi, also contributed to the growing disillusion and disrespect for the once all-powerful prince. In late 1969, Sirik Matak and Lon Nol humiliated Sihanouk at a conference of the Sangkum by forcing the closure of the state-run Phnom Penh casino in defiance of his wishes. By this stage, the possibility for compromise had disappeared.

Meanwhile, the war had escalated in the eastern border zones. In March 1969, the United States launched its secret bombing of communist positions in the east of Cambodia. B-52s pounded large areas of the countryside, with widespread loss of civilian lives and destruction of property, farmland and forests in a sustained bombing campaign. Cambodia was being sucked into the maelstrom and Sihanouk was powerless to prevent it. In January 1970, he went to his villa on the French Riviera to rest and regain his strength, and no doubt to ponder his political options. While members of the country’s elite believed that he should have remained at his post to handle his country’s mounting problems, it is possible that Sihanouk went overseas to plead with the leaders of the PRC and the USSR to lean on their Vietnamese allies to close or at least scale down their bases in Cambodia. He could then return home as a conquering hero, regain the initiative from his disgruntled courtiers and replace them with more pliable men.

Meanwhile, back in Phnom Penh, Sirik Matak struggled vainly to try to bring some semblance of order to the disintegrating system. He tried to negotiate with the North Vietnamese and NLF for a withdrawal of troops, but learned that Sihanouk in fact had secretly agreed to their presence. (It should be said, however, that Sihanouk was scarcely in any position to do otherwise, short of entering into a military alliance with the United States and South Vietnam, which would have meant the end of his country’s cherished neutrality and would not have guaranteed military success.) Mobs in Phnom Penh sacked the DRV and NLF embassies with Lon Nol’s covert support, demanding the withdrawal of troops from Cambodian territory. It is also likely that Sihanouk approved the demonstrations and planned to use them as a bargaining chip in his discussions with Russian and Chinese leaders so that they would bring pressure on Hanoi to close the bases. In the event, they turned into full-scale riots, with a heavy rent-a-crowd of hardline Khmer Krom soldiers flown in from South Vietnam by Lon Nol for the occasion. Sihanouk had wanted something milder, and was forced to denounce the rioters. If he had planned to storm back into Phnom Penh and retake the initiative, with a signed agreement with the world communist leaders regarding the bases under his belt, he was sorely mistaken. Sirik Matak and Lon Nol had taken over writing the script and the following day they ordered the evacuation of the Vietnamese bases and cancelled agreements that allowed them to funnel supplies via the so-called Sihanouk Trail from Kompong Som. When the DRV and NLF ignored the demand to withdraw, Lon Nol’s soldiers attacked the communist positions, with support from South Vietnamese artillery fire from over the border.

There is something precipitate, even hysterical about the Cambodian government’s actions at this stage, for it was unrealistic to think that the Vietnamese communists could suddenly close down their bases and withdraw their troops in the middle of an all-out war. Moreover, although the bases did infringe on Cambodian sovereignty and provoke the United States into military incursions, Hanoi and the NLF could point to their deal with Sihanouk as a legitimising factor. On 16 March 1970, last-ditch talks between the Vietnamese communists and the Lon Nol government failed to resolve the problem. Sihanouk’s delicate balancing act to maintain neutrality was over and from this point on the spread of full-scale war to Cambodia appeared inevitable. By March 1970, Matak had had enough. Sihanouk was still overseas while the country was sliding towards disaster.

There are times when the decisiveness or otherwise of a single individual decides the course of history. Although the Sihanouk loyalist Oum Mannorine attempted unsuccessfully to arrest Lon Nol on the night of 16 March, the General dithered. Fifty-six years of age, cautious and conservative, he had been Sihanouk’s creature since he was a young man. Sirik Matak, however, was resolute and more than an intellectual and moral match for the equivocating Prime Minister. He had lost all respect for Sihanouk sometime earlier, and he was determined that the time had come to remove Sihanouk from power. During the night of 17 March, Sirik Matak and several supporters burst into Lon Nol’s house, pulled him from his bed and demanded his support for a parliamentary coup against Sihanouk—at gunpoint, according to some reports. Reluctantly, Lon Nol agreed, signing a paper that called upon the National Assembly to depose Sihanouk as head of state. He is said to have wept when he signed the document, and later, when the country descended into chaos, to have expressed remorse at turning against his master.

The session of the National Assembly that followed was electric, as speakers stood to denounce Sihanouk for corruption and abuse of power, giving vent to howls of pent-up rage against the man who had often personally humiliated them. It was a revolt of men exasperated to the limit with a master who had forfeited their loyalty and respect. The assemblymen were not revolutionaries by conviction or nature. They were, by and large, the same conservatives who had supported Sihanouk since his overthrow of the Huy Kanthoul government in 1951, or men very much like them. They agreed with the plotters, voting by a margin of 86 to 3 to remove Sihanouk as head of state (later altered to be unanimous). It was the symbolic parricide of the father of the nation. Sihanoukism was dead, and some months later the mutineers voted to transform Cambodia into a republic. Cambodia, however, was rushing headlong towards catastrophe.