‘The Ditchley Portrait’ of Elizabeth I by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, c. 1592. When Shakespeare was born her England was a small place, nothing compared with the great contemporary powerhouses of civilization: Moghul India, Safavi Iran, Ottoman Turkey and Ming China.

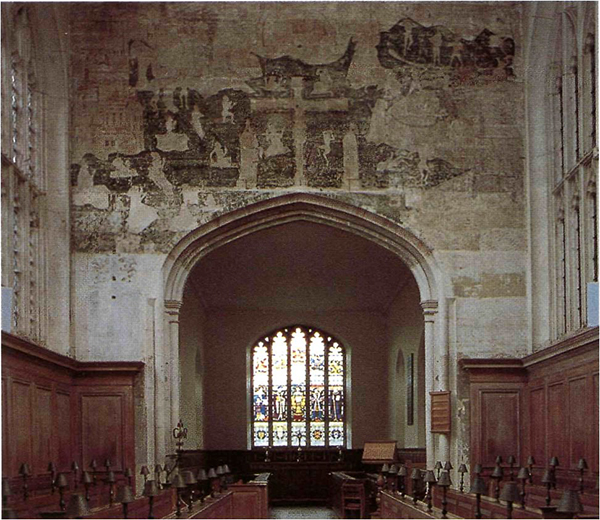

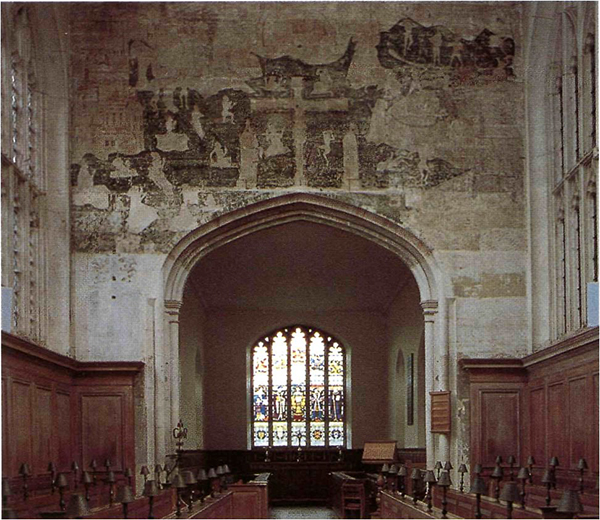

The guild chapel in Stratford today, showing the remains of the wall painting of Christ and the Last Judgement.

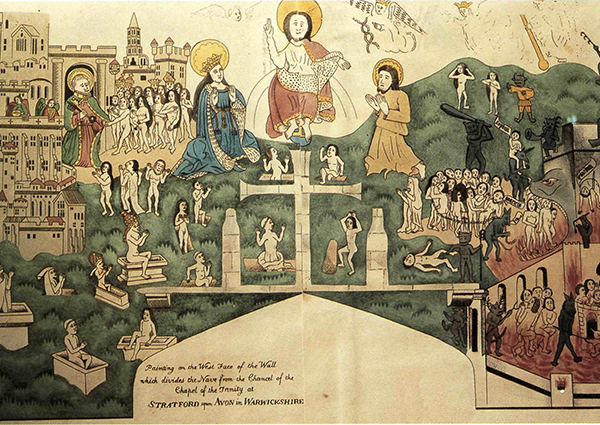

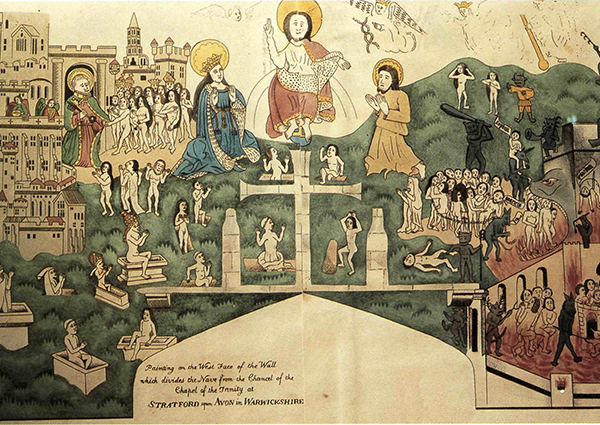

The mural, as uncovered in 1804. This was one of the images whitewashed by Shakespeare’s father in the winter of 1563.

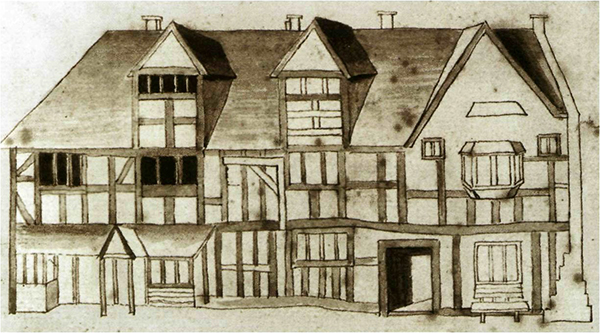

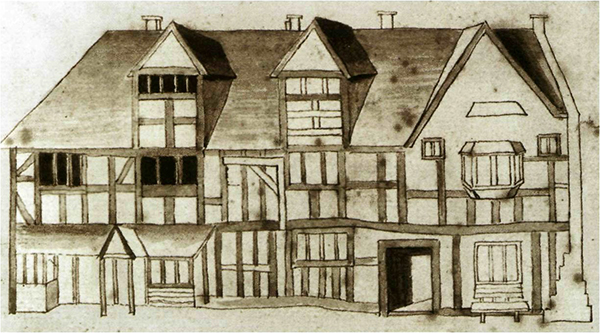

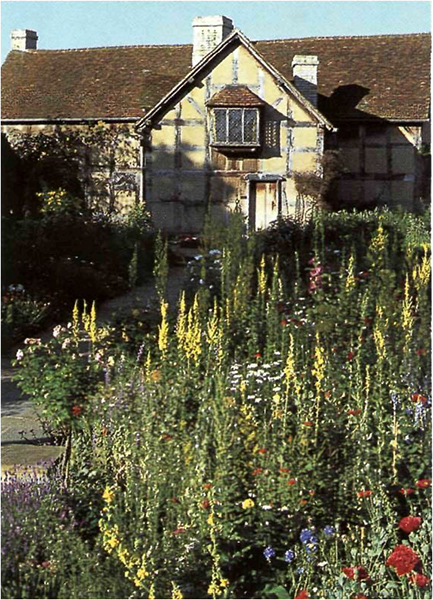

The Henley Street house as it was in 1769.

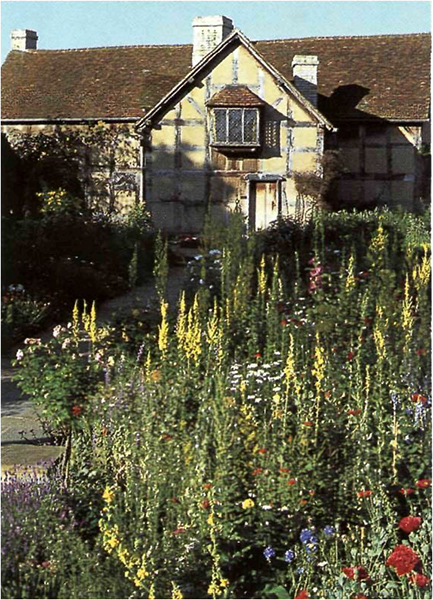

The house from the rear today. It is likely, but not certain, that Shakespeare was born here.

Anne Hathaway? A 1708 sketch from a Tudor portrait.

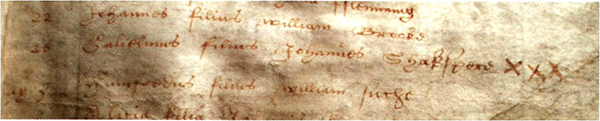

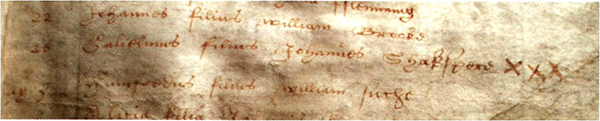

The original entry in Latin for William’s baptism, 26 April 1564.

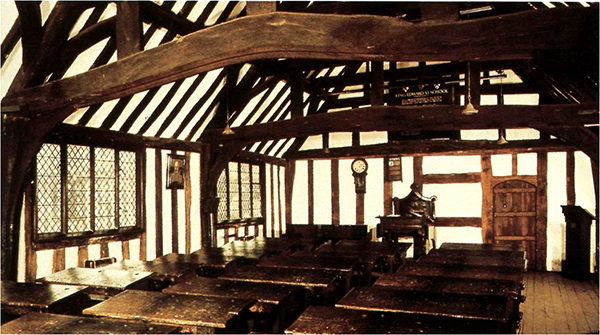

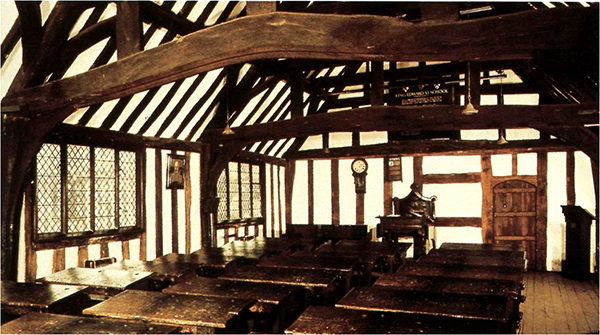

The first-floor schoolroom in Stratford’s Guildhall, where William studied from the age of seven.

A Flemish Protestant family of the middle class in the late sixteenth century. This was the kind of material life to which Shakespeare’s parents aspired.

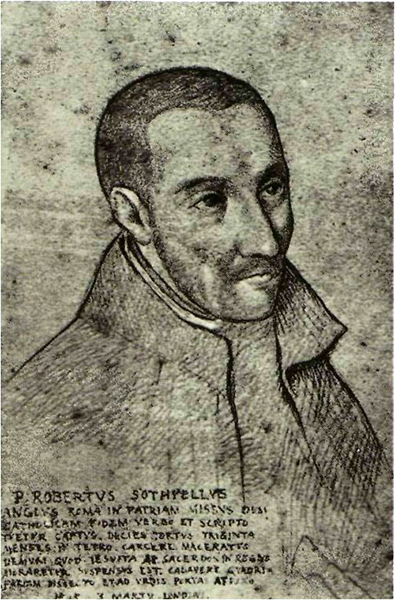

Edmund Campion, whose 1580 mission was a turning point in the ruin of the English Catholic community. It appears to have sucked in Shakespeare’s father.

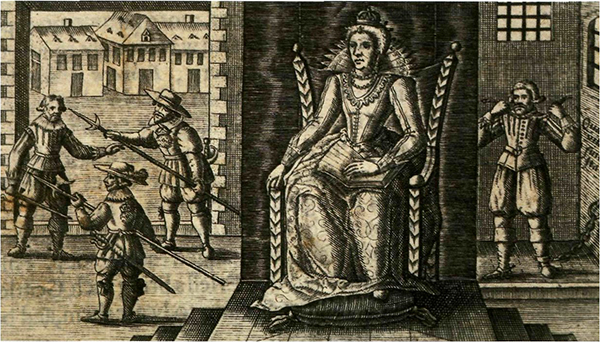

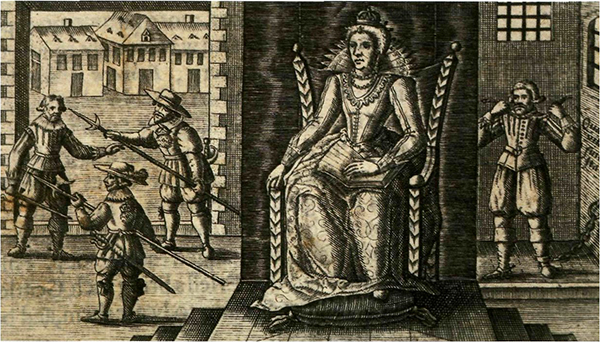

The Arden-Somerville Plot. Somerville is arrested (left) and strangles himself in prison (right). The plot touched Shakespeare’s family, but William retained his Arden links and was a friend of Somerville’s brother.

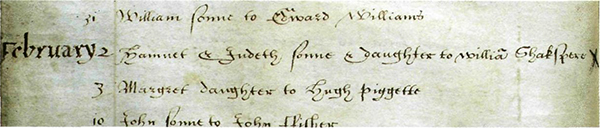

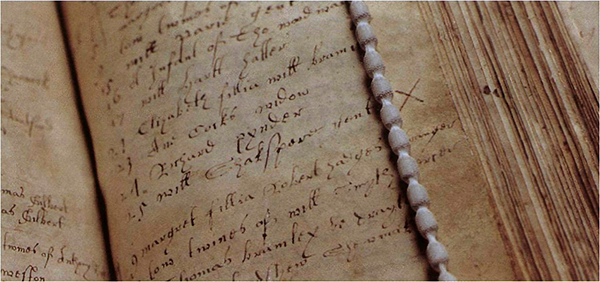

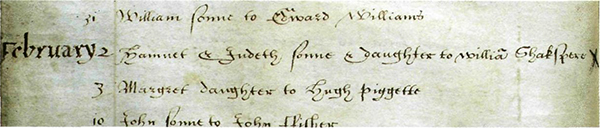

The baptism register of William’s twins, Hamnet and Judith, who were named after his Catholic neighbours, the Sadlers. In 1585 William had not abandoned the old social and religious loyalties of his family.

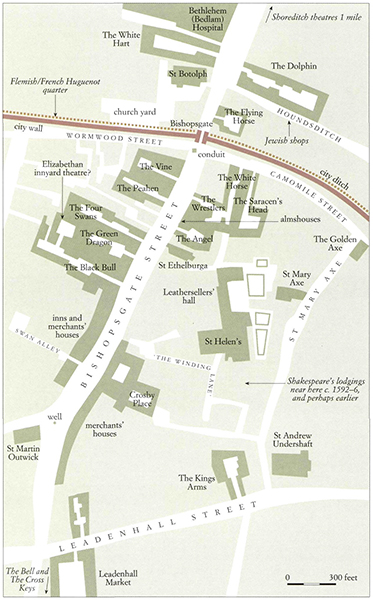

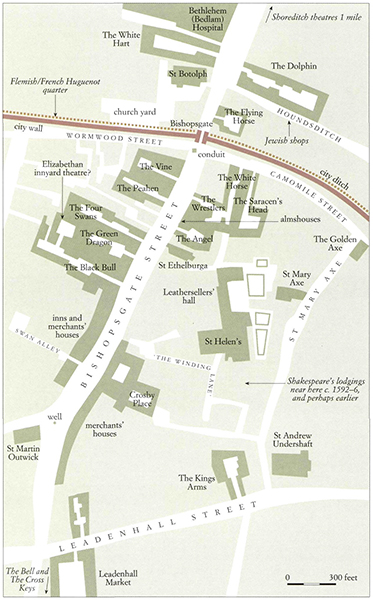

Bishopsgate and the theatre inns – Shakespeare’s first known address. He lived close to St Helen’s until 1596. Among his neighbours were the madrigalist Thomas Morley, the poet Tom Watson and the sinister spy Robert Poley.

Middle Temple Hall, where Shakespeare played Twelfth Night, is still used by lawyers for feasts and plays.

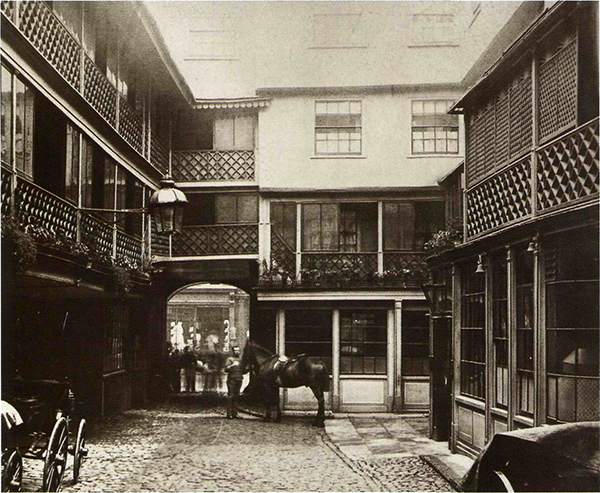

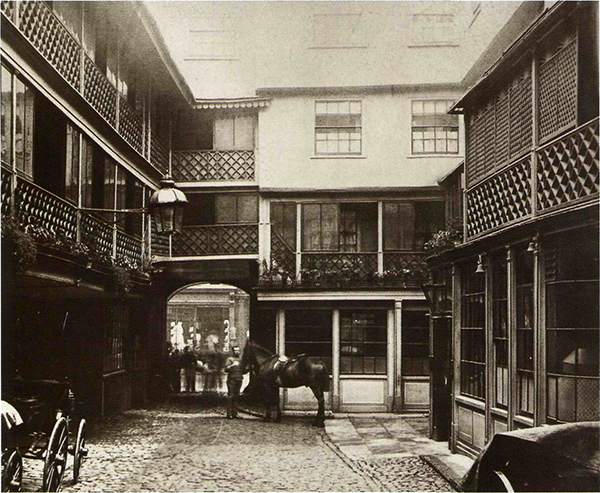

The Green Dragon inn, a base for Suffolk carriers. This photograph was taken c. 1880.

An unknown Elizabethan aged twenty-four in 1588, the same age as Shakespeare in the year he perhaps came to London. It closely resembles the Folio engraving, so could this be a portrait of the artist as a young man?

The comic Richard Tarlton, with tabor and pipe. ‘A wondrous plentiful pleasant extemporal wit’, Tarlton drew packed crowds in town halls up and down the land; the queen herself was a fan.

A detail of a presumed portrait of Marlowe at Cambridge in 1585, aged twenty-one. The superb padded doublet with its bossed gold buttons suggests a flashy undergraduate ‘ruffed out in his silks in the habit of a malcontent’.

The Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s patron, c. 1594. ‘The dear lover and cherisher as well of the lovers of poets as of the poets themselves,’ wrote the journalist Thomas Nashe.

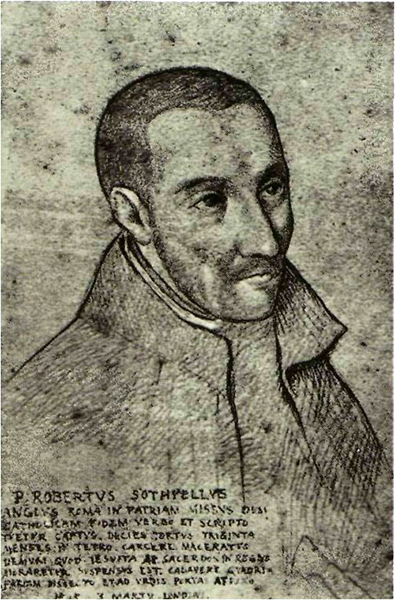

The only known image of Robert Southwell. The marks of privation are clearly visible in his face.

The coat of arms designed by the College of Arms for John Shakespeare in 1596 for his ‘posterity’ – ten weeks after the death of his only grandson.

The view from Southwark across to St Paul’s. Southwark was the centre of the Elizabethan entertainment industry – ‘a licensed stew’ as one Puritan preacher called it. The area contained 300 inns and brothels, some mentioned in the plays Shakespeare wrote when he lived here.

Sixteenth-century houses in Bermondsey Street, Southwark, which were still standing in 1893. In Shakespeare’s day the street was the haunt of ‘fences’ who disposed of stolen goods.

William Herbert. No youthful image survives of the beautiful boy, who attracted devotees of both sexes, including his ‘servant’, Shakespeare.

Mary Herbert, c. 1590. Patron, poet and editor, Mary was adored by poets for her generosity and her intellectual powers. Shakespeare used her manuscript play on Antony for his show on the same theme.

Ben Jonson, who sniped at Shakespeare’s ‘Tales, Tempests and other such Drolleries’ but ‘loved him this side idolatry, as much as any’.

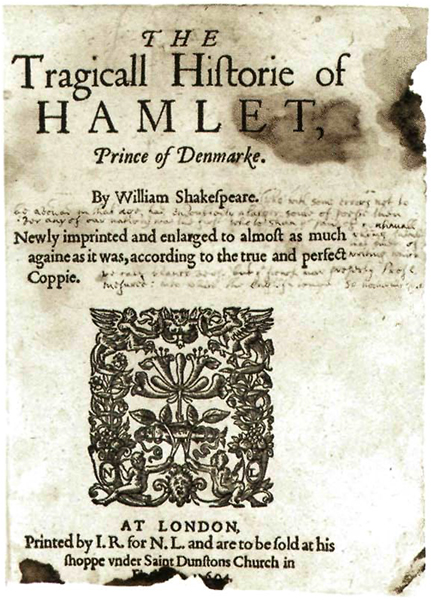

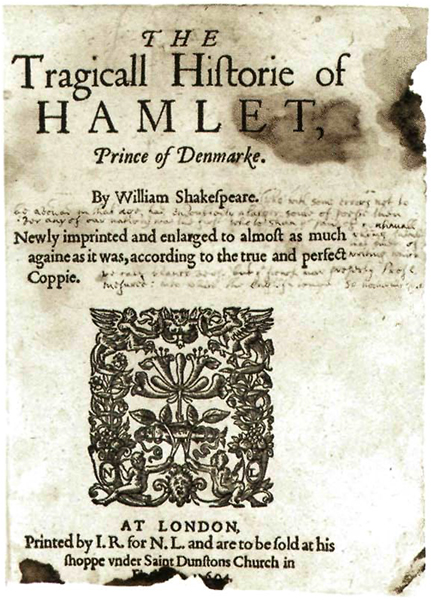

The 1605 printing of Hamlet advertised bonus scenes. ‘The younger sort takes much delight in Venus and Adonis,’ wrote one contemporary, ‘but Hamlet pleases the wiser sort.’

London c. 1605 with the Globe theatre in the foreground and the magnificent St Paul’s across the river.

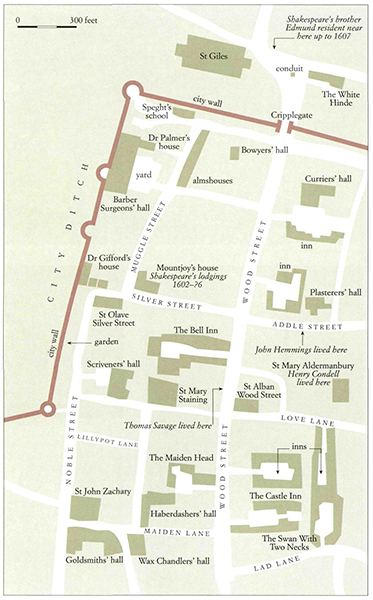

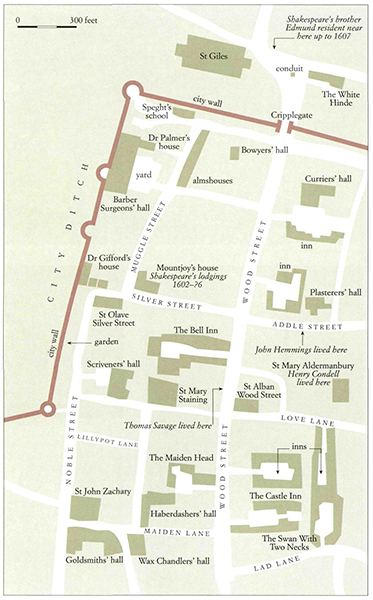

Shakespeare’s neighbourhood from 1602 to c. 1606. Silver Street was the home of gold- and silversmiths, and several of Shakespeare’s theatre colleagues lived close by, including John Hemmings.

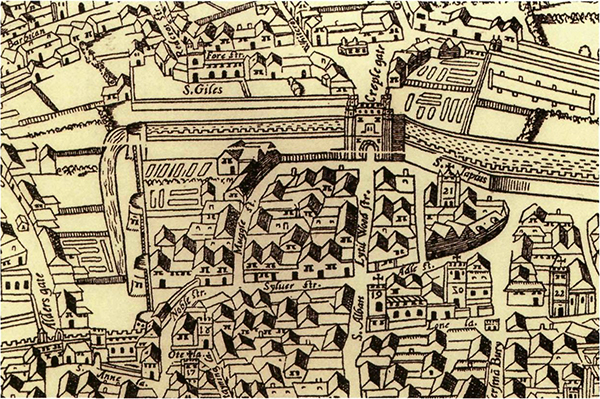

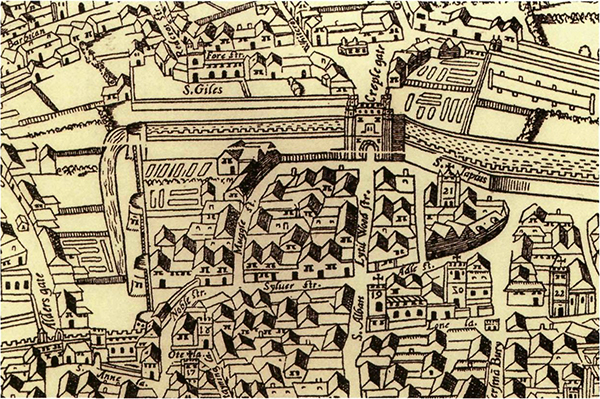

The Agas map (c. 1558) shows Shakespeare’s house with a double gable on the corner of ‘Muggle St’ and ‘Sylver St’.

Richard Burbage. Recent restoration of the portrait suggests he had a drinker’s nose.

A noble Moor. The Moroccan ambassador painted in England in the winter of 1600–1.

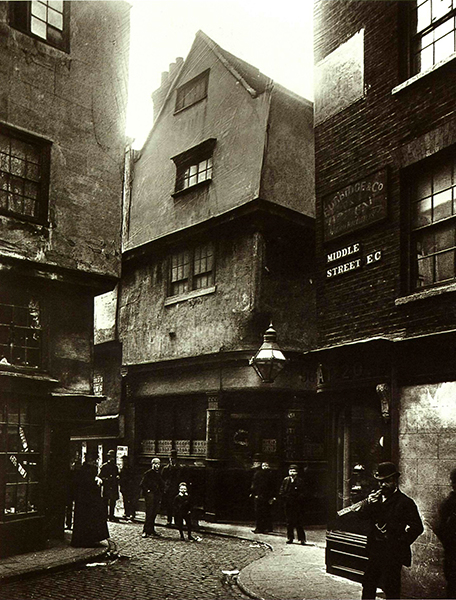

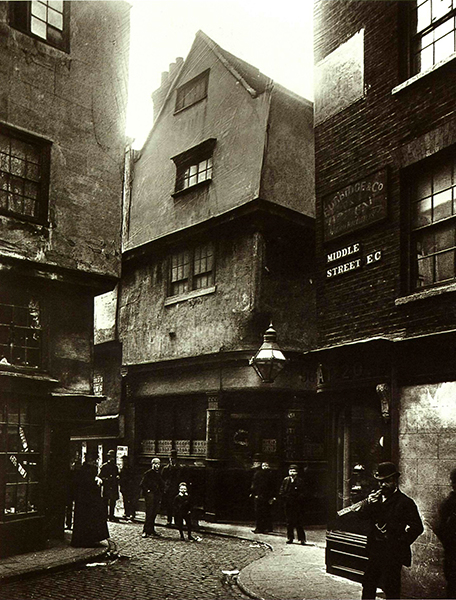

Sixteenth-century housing at Cloth Fair, Smithfield, demolished in 1900. This gives some idea of how the corner of Silver Street would have looked. The Mountjoys’ house was probably of three storeys with an attic.

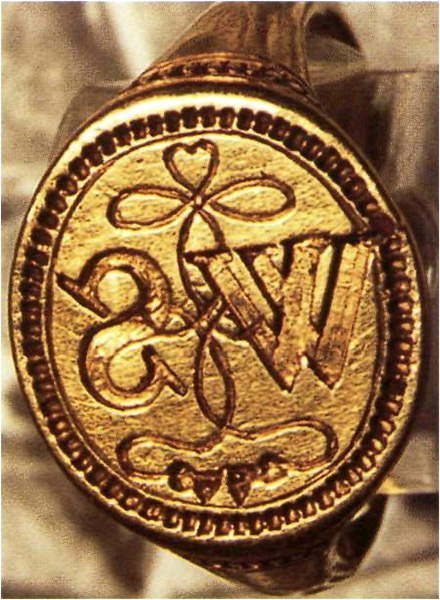

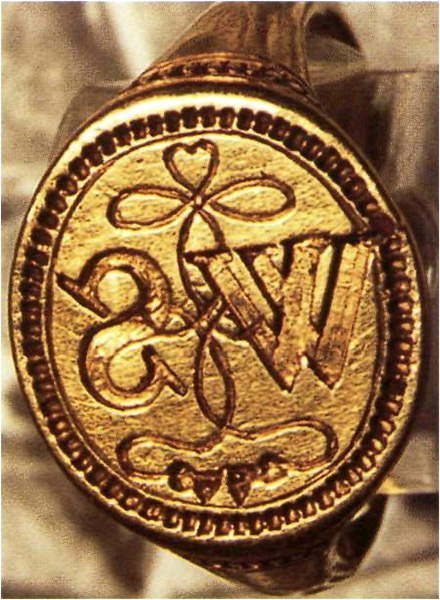

Shakespeare seems to have lost his seal ring early in 1616. It was found near Stratford church in 1810.

Shakespeare’s signature on his will, March 1616. The pronounced deterioration in his handwriting in the previous four years suggests a degenerative illness, perhaps alcoholism.

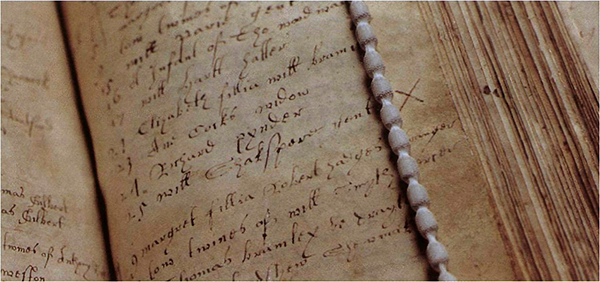

The burial register of William Shakespeare, ‘gentleman’, 25 April 1616. By then he was a pillar of the local community. Later the story surfaced that he had received the last rites as a Catholic. If true, it would be typical of the torn loyalties of so many of his generation.