THE GREENLAND SEA, 1931

While I was still wondering what to do with the Morrissey in the summer of 1931, Jimmy Clark, director of taxidermy at the American Museum of Natural History, called me on the telephone and asked me to see him. When I got there he said, “I’ve got a fine fellow for you who wants to hunt muskoxen in northeast Greenland. He hasn’t much money, but he is anxious to go, and if you can do it fairly reasonably, he is your man.”

The young man proved to be a chap named Arthur D. Norcross, and when we met it didn’t take us long to arrange the Norcross-Bartlett Expedition to the Greenland Sea, and I started making plans. Mr. Ali, of the Standard Oil Company, said he could help us out, and we got a real break when I ran across Ben Smith, president of the Standard Motor Company, manufacturer of the Morrissey’s engine, and he told me that Mr. Di Giorgio, president of the Greenheart Company, would let me have enough of his product to sheath the Morrissey all over. I had been worried about the ice conditions, for we had been lucky on the 1930 trip, getting into the Greenland coast easily and very early, and I knew from past experience that no two years are alike in the north. Consequently I had a strong hunch about ice, and I believed we should sheath the Morrissey, an expensive job.

It seemed too good to be true, this news about the greenheart, but the wood arrived at Staten Island in due course, the planks were steamed to make them pliable, and fastened to the hull with five-inch galvanized iron spikes. We were all ready for the ice with that sheathing, and I hope it will last for 10 years. The added 20 tons of weight only increased her draught about two inches, and improved, rather than hurt, her sailing and steaming qualities. I also had new bow plates welded on the stem plates from the turn of the stem to the light load line. I drove lots of iron into her keel, too, as she gets some of her worst pounding there.

I have mentioned greenheart before, but I should like here to tell something about it. It is a member of the laurel family, and grows in South America and British Guiana. Years ago the Scotch, English, and Norwegian whalers discovered this wood, and used it to cover the outside skin of oak to keep it from being broomed by contact with the ice, which, especially in the comparative warmth of the summer, loses its soft snowy cushion and becomes hard as granite. Oak is splintered by contact with it, but greenheart has a smooth, hard surface, like marble, and the more the ice rubs it, the smoother it becomes. Ever since then vessels that have to work in ice have turned to this wood for protection.

While this was being installed, I was getting additional aid for the trip. The Smithsonian wanted more specimens of marine life. The Heye Foundation gave me $200 for some specimens they wanted. The American Museum of Natural History desired us to get a number of Arctic birds. All in all, we had a good many angles to cover, and had to make some changes in our crew. The Botanical Gardens wanted some live and pressed flowers, and I signed on a third engineer for this trip, Jack Angel. One of his jobs was to go ashore and collect the flowers. In addition, he could handle the engines when Junius Bird, who could live indefinitely away from the Morrissey with a tent and a bit of grub, was on shore. My old chief engineer, Jim Dove, signed articles for a matrimony cruise with a girl from New Jersey, and couldn’t go rambling anymore, as he had a job and had to keep it. His brother, Robert Dove, came with us as surgeon and ornithologist. He was a medical student at Dalhousie University at Halifax. Jim was replaced by Len Gushue from Brigus. Junius was second engineer, and altogether our set-up was a perfect one, working smoothly at all times.

We got away on May 31, and by June 7 had rounded Cape Race. We used constantly my new patent sounding lead with my Bliss Tanner and the many tubes I received from the Navy Department through Captain Helwigg, superintendent of the Naval Observatory. With these instruments I was able to feel my way through dense fog right into the cape. What wonderful assistance science has given navigators! Only today I was reading about Doctor Forbes’s survey in northern Labrador with his schooner Ramah. He negotiated all the intricate passages, many of them uncharted and unknown to him, without a pilot. He went the whole stretch of the Labrador coast without grounding once, using Professor E. P. Magoun’s submarine kite in two motorboats that preceded the schooner and marked the safe channel.

While we were at Brigus, where we remained for three days, I could see a big change for the worse in my father’s appearance, and when we sailed I was convinced that I was looking on his face for the last time. It is a hard thing to leave someone dear to you when you feel that way, but we had to go, and go we did, having an excellent passage to Reykjavik.

Once there we met a man named Snaabjorn Jonasson, official English translator in Reykjavik, and proprietor of a store there known as the English Bookshop. I could use many pages in telling of the fun we had there with him, but space does not permit, and I shall content myself by saying that we had an excellent time, saw many interesting things, and are much indebted to him. He spoke excellent English, when he told me that he had married a English girl, I said, “Oh. Now I know why you speak such excellent English.”

“No,” he replied casually. “I was at Oxford for five or six years.”

Jonsson introduced me to Doctor Bjarni Sarmundsson, in charge of the Museum of Natural History at Reykjavik, and one of the great authorities on birds, fishes, and mammals. He is the kind of a savant, so far as I could see, who does not take himself particularly seriously, reserving that feeling for his work. He showed us the old, fossilized forms of life, and explained them so simply that even my lay mind could grasp a little of what he was driving at. It was fascinating to hear him discourse on the these specimens from the Miocene period, and I enjoyed it thoroughly.

We also got a chance to inspect the Iceland cod fishing industry functioning. This island is a great place for cod these days. The shores and banks abound in cod and halibut, and there are natural drying beaches. The fish are caught by the smaller boats, cleaned and salted, dried and shipped to the countries bordering the Mediterranean, as well as the West Indies and South America. The Icelanders are very painstaking in their work, and this has given them first place in the fishing world. The great stretches of lava make an ideal drying place, as the wind passes underneath, helping the work, and keeping the fish from becoming sunburned. All the curing is done by women, and they are very careful to do a good job. In Newfoundland we have the best codfish in the world, the best bait, and the most favourable water temperature, but the curing has been neglected and we have lost the lead.

But again we had to move on, and on June 26 we hove up anchor and put to sea, to be tossed around the tide rips and the steep swell. Birds were plentiful, murre, puffins, and gannets abounding. Dolphins swam happily along beside the Morrissey, and we saw many bottleneck whales swimming along like mad and looking like nothing so much as a field of horses crowding neck and neck on a fast track. This whale, which is toothed and next in size to the sperm whale, the largest species known, owes its name to the fact that its forehead is domed in the shape of a big hump resembling the shoulder of a bottle, while its jaws project like a slender beak or bottleneck. When it swims on the surface, its forehead alone shows above water, and may easily be mistaken for the most forward part of the whale. In the female this head cavity is filled with transparent oil containing spermaceti, which is carefully preserved by whalers. The female may measure up to 25 feet in length, and will yield from a ton to a ton and half of this oil. The male is larger and the dome contains a solid lump of fat instead of oil.

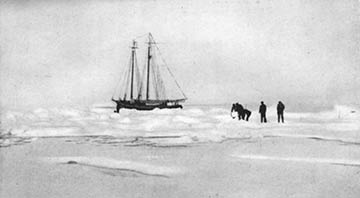

By midnight of June 29 we had struck the ice, along with heavy fog that forced us to use the thermometer. The ice extended a lot more to the eastward than our course, and I realized that my hunch about the greenheart had been a good one. The floes were well south and very wide, as evidenced by the short time required to pick it up after leaving Iceland. The fog lifted a little around noon the next day and on rounding the point of the ice we could make good northeast by east. Hopeful of seeing a bear, we followed the edge, and had it remained clear I think we might have found a break that would have carried us to the fast ice off Cape Hold With Hope. Instead, it came in thick as mud, and we couldn’t try it.

If we needed any reminder in addition to the ice, that we were back in the old stamping grounds, it was furnished when we saw large schools of harp seal, known to the Norwegians as saddlebacks, and to the Greenlanders as svartside, or blackside seals. I have seen this species all over Hudson Bay, Foxe Channel, Kane Basin, north of Cape Bismark, and in many other places. It was like old-home week to spot them now. The adult male is five or six feet long, greyish white in colour, with a black patch shaped like a harp on each side.

We were now 150 miles west of Jan Mayen Island, working through that pea-soup fog. Independence Day came along, and we celebrated with a royal spread that Charlie Pope, head of the commissary department, and Billy Pritchard, the ship’s cook, had been preparing for many days. The meal did justice to their efforts, and I give here the menu, so that you can see what can be done on a small schooner in the Arctic when the cook sets out to spread himself:

Hors D’Oeuvres.

Tomato Juice Cocktail.

Queen Olives.

Florida Preserves.

Mixed Pickles.

Roast Newfoundland Veal á la Pritchard.

Sweet Potatoes.

Tiny Beets.

Sweet Green Peas.

Blue Goose Orange Ice.

Chocolate Layer Cake.

Mixed Nuts.

Layer Figs.

Candy.

Petit Gruyere St. Bernard.

Toasterettes.

Coffee.

Cigars.

Champagne.

Cherry Brandy.

Mumm’s Cordon Rouge Tres Sec.

Marie Brizard et Roger.

This was handsome chow, and we stowed away quite a cargo before our hatches were full up, and when I got on deck again I calculated that we were as far north as I wanted to go. I knew from experience that there should be a break in the ice that would take us into the latitude of Bass Rock and Shannon Island, so I waited around for the fog to lift. We did some seal hunting to put in the time, and as we were hard at it a steamer broke through the fog. She was the Gustuv Holm, and she was hooked up, as her skipper had heard that a Norwegian vessel carrying some Americans had got into the land. The fog cleared the next morning, and there she was, stuck about two miles in from the edge of the ice.

At about the same time we spotted a polar bear, but before we could go after him the fog shut in again. The ice was heavy, so we tied onto a big pan, filling our water tanks from a freshwater pool on it, but we did not stay there long, as we saw a lake of open water making to the southwest. We followed it, found that it ended blindly, and returned to the pan. The Gustuv Holm had worked her way out of the ice, and our old friend Gothaab appeared to the northwest. We were shut off from our objective, and it was disheartening to be held there. However, we collected as many birds as we could for the Museum of Natural History, put seal stomachs in alcohol for the Smithsonian, and collected some interesting specimens in the pools on the old, dirty ice. The plankton net, too, was constantly busy in an effort to get a decent collection for Doctor Schmitt, curator of marine invertebrates at the . We were a long way from the muskox hunting grounds, but Norcross never complained, but rather kept eagerly at the work of collecting seals and birds and making pictures.

Lanes of water finally opened in the ice, and we went in, making good progress until the inevitable fog returned. Being in the latitude of Shannon Island, the prospects looked good. Late at night the fog again was blown off, and we could see land plainly from the deck. As we saw many schools of harp seals, I felt that we were on the right track, and that if I watched for leads there might be a chance to get into the land. Someone spotted a couple of bears as we steamed along, and we lay to while these were stalked, shot, and brought aboard. The ice continued to open, and we worked into a lake of clear water.

As we steamed along the auxiliary schooner Polarbjorn came alongside, carrying the Norwegian East Greenland expedition under Doctor Adolf Hoel, with a large staff of scientists who were very keen to reach the land as soon as the Gothaab and the Gustav Holm, which was carrying the Danish expedition under Doctor Lauge Koch. At this time the ownership of East Greenland was being settled in the World Court at The Hague, and there was great national rivalry between the two groups. The schooner broke her way through ice that the Morrissey couldn’t attempt, and continued looking for a way. They were giving her all she could stand, and I’m glad I didn’t have to foot the repair bill when they finished with her. The Polarbjorn was to come to our assistance later on, but right now I would have bet the other way.

It was here that we saw hood seals for the first time on the trip. They are next in size of the bearded or square flipper, seal, and the male measures about eight feet. This species somewhat resembles the sea elephant of the Pacific, and prettily marked, its back being covered with short, dark hair. Its name comes from the way it inflates its nose when angry. I remember the first year I went sealing with Father in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. We struck the herd between Anticosti and the Magdalen Islands, and loaded in a few days. Father wired the owners, telling of the number of seals we had, and they could not understand how we could be full up with only 8,000 hoods. But some of them weighed as much as 700 pounds, and that covered only the skin and fat. They’re big fellows, all right, and well worth taking.

After the Polarbjorn parted company with us, we were locked in the ice for several days, and I was afraid that the drift might carry us to the southwest, and cost us valuable time. Therefore when the ice opened a little we tried to work into a lake of open water about a mile away. It took us six hours to cover that mile, and God alone knows how much hard work. In addition to the Morrissey’s power, we used dynamite to blow out a channel, and prizes to get broken ice out of our way. Under the pounding those heavy bow plates broke away where they had been welded to the stem, and they were doubled back as though they were made of paper. In addition, many of the bolts were loosened, so that when the Morrissey finally made the lake, I set a gang to work with hacksaws, punches, and chisel bars to cut the bent edges and to tighten up the bolts. Then the bent edges were smoothed out, with an improvised battering ram. It was very difficult work, as most of it was done three feet below the surface, and the crowd was dog tired by the time it was completed.

In the meantime the Polarbjorn was in plain sight, steaming around like a dog with a can tied to its tail, but she wasn’t getting anywhere and was just burning up good oil to no purpose. I saved mine, for I felt that when the ice opened, the break would come about where we were, and if it came elsewhere, we could see where the Polarbjorn went and follow her. So we kept on with our collecting of specimens with the dredge and the plankton net until the last day of July, when the ice began to open. We cast off from the pan to which we had been moored, and steamed into a promising lead. We were going well, and everything looked fine when the fog shut in, and then we ran into many blind pockets. The ice was running at great speed in the tide and current, and was wheeling, which meant that I had to watch my step lest I get hung up on the corner of one of the big pans while other floes nipped us. That would have been the end of the Morrissey. And in the meantime, with the blinding fog, we had to take it easy. Time was passing, the autumn would soon be with us, with the young ice, short days, and north winds jamming the ice on the land.

We jockeyed around with not the faintest idea of where we were, our immediate problem being to keep in open water, until the fog thinned a little, and we felt our way along, being careful not to blunder into a cul-de-sac with too little room to turn and get out, to be smashed like a peanut in a strong man’s fingers. Our progress was necessarily slow, and the delays were exasperating, but you learn patience in the north, and we consoled ourselves with the thought that we were moving in the right direction. When the sun finally burned through, we found that the leads had widened, and we were able to make real progress. It was good to see the steel stem plate cutting the dark blue water, with the pans of ice sliding by, and August 4 we were inside the 100-fathom curve.

We continued on in through lakes of open water and loose ice, bringing up finally at the touching point of two big sheets of ice. Twenty plugs of DuPont seven per cent dynamite did nothing at all. More plugs were set down and touched off, shaking the ice where it was nipped, and in three hours we used three boxes of explosive. The ice was cracked, all right, but the pressure kept it so closely packed that we could not force our way through. And our work almost cost us the schooner, for the current changed where the two points were nipped, and if we had broken them so badly that they gave way, the sheets would have come together, with the Morrissey in between. She would in no time have been an object of considerable interest to the manufacturers of match sticks. For a day we waited nervously to see what would happen. The points held, fortunately for us, until the current changed, and the lead opened again.

On we went and finally a single big sheet barred our way into the open coastal water. Ten plugs of dynamite blew it to smithereens, and we were free at last, after 37 days at the mercy of the ice. That was a long time to be held, but we were still all right, and we anchored alongside the Gothaab and the Gustav Holm, to the blank amazement of their captains, for they had found ice conditions very bad, and did not believe we could work through as quickly as we had. Our anchorage was at Eskimonaes on Clavering Island, and the gang quickly went ashore, Norcross with Charlie Pope, Pyman Smith, George Richards, and Harold Batten after muskox, Robert Dove to get what small game he could, and Jack Angel seeking flowers.

I spent several hours with Doctor Koch, receiving permission for our men to do their hunting and collecting, and hearing his ideas for research. He planned to erect a large station, with wireless, for the scientists, one of several along Scoresby Sound and further north, and to return to Denmark with the supply ships as soon as things were settled. Doctor Koch was in charge of all the stations and the entire project, and he could best handle things from Copenhagen, spending the winter correlating the results of the summer’s work of all the posts. This seemed to me a highly intelligent approach to the task, and likely to produce successful results.

When Norcross came back he reported having a grand time, getting two muskoxen and seeing many more. Shooting them a long distance from the water entailed a lot of hard work getting them back to the whaleboat, but our fellows were hardened up to it, as they sometimes spent their winters in the lumber camps. Norcross also brought back with him a few barnacle geese and Arctic hare. Jack Angel made a fine collection of flowers, and Robert Dove turned up later with three Arctic hare, some rock ptarmigan, and a number of small birds. He had travelled along the shore to the hut where Junius Bird had summered the year before, and reported game scarce.

When everyone was aboard we hove up anchor and went to Cape Stosch, about two hours run away. Norcross and his gang taking ashore what gear they wanted and making for Loch Fine, where I thought they would be able to get some game without having to travel too far in search of it. I would have favoured some hiking to harden them up, but there were only a few days left, as we had to get out very soon, and we could waste no time

The hunters counted on being gone for two days, so Len and Jack did some work on the main engine, which showed the results of all that use in the ice. I went ashore, landing on the north side of Clavering Island, looking for live plants for the New York Botanical Gardens. We quickly filled our Wardham cases at Cape Stosch and returned to the schooner. I enjoyed that morning on shore, near where we had collected the Eskimo relics the year before. Many of the flowers had gone to seed, as we were about two weeks too late, but the bumble bees were still hanging around for the last drops of honey. The willow was beginning to take on a red and tan colour; and the other plants showed clearly that the end of the season was near at hand. The streams were now mere rivulets, where a few weeks before they were turgid rivers fed by melting snow and glaciers. Old Sol was losing his warmth.

The geese were walking along the shoreline teaching their young to fly and swim in preparation for the long trip to a new land, where they would still have summer and warm weather. It was quite a sight to see the mother goose pushing the goslings one by one into the water. The days of carefree existence would soon be over for the young ones, and those that did not play the game and go into training would fall by the wayside. The north ruthlessly weeds out the unfit. Life exists there under the hardest possible conditions, and no mercy is shown.

I took pains to get our plants up in good condition with as much of their native soil as possible clinging to the roots, and it was a nice-looking collection. Little did I think that as I got them to the threshold of their adopted land they would be mauled and wantonly destroyed by men who should have known better but didn’t give a damn as long as they drew their salaries. They didn’t care about flowers, and were nothing but government-bureau machines. I know that we must be careful lest we introduce some insect pest into the country that might run wild and play havoc on our crops, but I am sure we can protect ourselves better than by sending a crowd of inspectors of that hard-boiled type aboard vessels coming into port with specimens for scientific organizations.

Late in the afternoon a day or so later the Norcross party returned, having had good hunting, and bringing several muskox heads, numerous birds for the collection, and two downy young glaucous gulls caught by Pyrman Smith. Early the next morning we hove up and steamed out from shore, taking it easy, as I was towing the dredge. I was watching this pretty closely, as were the rest of those on deck, and none of us noticed the ledge of rocks that ran about half a mile offshore. I knew about this shoal, of course, and if I had been paying attention to the schooner, as I should have been, instead of the dredge, we’d have been all right. Instead we piled right on it, striking easily at the very top of the night flood tide.

It seemed more of an annoyance than anything else, and I rang up full speed astern. Nothing happened, and at the next high water she was still caught just under the engine bed. The wind was blowing out of the fjord, keeping the sea from piling in, and that didn’t help us any. I didn’t want to land my oil or ballast, as I was in a hurry, so we signalled the Polarbjorn, which came to our assistance. She tried to pull us off, using our five-inch hawser, and it broke repeatedly. Then we tried his wire cable, and snapped that twice. The third time the Polarbjorn went off at right angles to our stern, and when that cable took the strain what it did to our rail and some of our gear was a shame. Those stern chocks and the breather valve on the water tank must be going yet. And still the Morrissey stayed where she was.

We started in after supper and moved everything between decks to the bow, moved all the coal forward, put the deck cargo in the bow, filled the dory with water and hoisted it up to the bowsprit. At low water with all this weight forward, together with natural causes, she listed so heavily that we could hardly climb the deck. The Polarbjorn waited until high water and then gave us another line. I hoisted the jibs, started the engine, and had the whaleboat take a line off our port bow. With all these forces working for us, and with the wind hauling to southeast and piling water into the fjord, we floated.

We then anchored, picked up our lines and kedges, and began to clean up the mess on deck. And before the job was done, a strong Foehn wind came across the fjord and with the flood tide it kicked up an awful rumpus. We had to heave to, hoist the foresail and then work over under Jordan Hill. In taking up the kedge anchor, one of the buoy lines fouled the propeller, and that made more trouble. Going over the damage we sustained, I found my new hawser was ruined, my rail broken, the pin rail around the mainmast obliterated, and about 100 fathoms of old line gone. All this was climaxed, when I returned to New York, by the receipt of a bill for $250 from the owners of the Polarbjorn for towing and general salvage work. The Morrissey herself was all right. She did not leak a drop, her keel was unhurt, and the cement was not started in the garboard seams.

We sailed back to Eskimonæ and anchored near the Gothaab. Her crowd wanted to know why we hadn’t asked them for help, and they seemed almost hurt that we hadn’t called on them. I explained that the Polarbjorn had been nearer to us, and I also tried to tell them how much I appreciated their desire to be of use to us. That sort of thing does a man a lot of good, and we tried to show our appreciation by sending them all the meat we could spare, as they were too busy to do much hunting.

After clearing the line fouled on the propeller by using long-handled chisels, we hove up anchor, dipped our flag to the Gothaab, sounded our whistle, and steamed over to Shannon Island, making it without trouble, as the coastal waters were free from ice. We had really planned to go into the Hochstetter Foreland, but we saw a herd of muskox on Shannon Island, and as it looked like a good opportunity to make pictures, we stopped. Norcross, Pyman, and two sailors went ashore, finding the herd near at hand, asleep on a big patch of snow. Large boulders offered good cover, and the party got close enough to make beautiful pictures. Not a shot was fired, but the cameras did plenty of grinding.

Once they were aboard again, we headed offshore from Bass Rock, and struck the ice after about 25 miles. Our clutch had been giving us trouble, so we tied onto a big pan and made repairs, finding all the bolts more or less twisted and broken. By the time everything was fixed up the ice had begun to move apart, and we steamed into an open lead. For six hours we never stopped, nor did we encounter ice in our path, although the leads narrowed at times. Big unbroken floes, many of them miles in circumference, and with no pressure ridges, had filled up the leads we had used coming in.

Up in the crow’s nest, 94 feet above the deck, you don’t get a very good idea of the ruggedness of those floes, but when you come down and step off the sheer pole of the fore rigging and see the ice towering above you, the Morrissey’s small size is convincingly brought home. From aloft there was hardly a hole of open water to be seen except the one we were in, and we were lucky to strike the right way out. Even so, I had some uneasy moments during the forenoon. At times our way seemed barred, but a light breeze tended to counteract the trend of the current, and helped keep things open for us.

I was still toying with the idea of going on to Hochstetter Foreland, but the soft southern appearance of the sun somehow gave me a hunch that now was a fine time to get away. In this decision I was strongly influenced by radio weather reports from all over the Northern Hemisphere. I have noticed that always in these parts the forecasts are very reliable, and I govern myself accordingly. No one who has but been there can know what a comfort it is to get daily reports from Greenland, Franz Josef Land, Spitzbergen, and Jan Mayen Island. This enabled me to tell, 24 hours in advance, approximately what the weather conditions would be. With the ice spewing out of the Polar Basin this is reassuring, for 24 hours’ notice may enable one to avoid serious trouble.

As we steamed along I detected the water sky, and after a bit, lanes of water began opening out fanwise from the axis of our course. Then we began to spot the little auks and Fulmer gulls, a sign that the main water was near. The leads were such that we could go in almost any direction we chose and from 8:00 p.m. to midnight we were in loose ice, and we could feel the schooner rise and fall to the swell. Fog is never long absent in the north, and it shut in now, forcing us to lie to, the time being spent in policing on the deck. When it blew off, we resumed headway, and worked through heavy loose ice into a lake of open water. On August 17, a light string of ice to the eastward forced us to run south, paralleling it, and then we came to more loose ice, cutting through it.

This was exciting all right, for we were in a heavy swell and couldn’t turn back, as that would mean getting her athwart the points of the growlers. I was aloft, and I hadn’t had so much excitement since I took the Morrissey through that nest of growlers in the Arctic Ocean north of Alaska. It was touch and go, keeping her end on and dodging in and out through the lanes, which would sometimes be wide, and sometimes too close for comfort. The ordeal lasted for 20 minutes, with all hands, including the cook, on deck. The last of it was the worst. Open water lay ahead of us, and we were going between the points of two big growlers, when they suddenly began to close in, gyrating wildly in the swell. The fraction of a split second’s delay would have finished us, but I yelled for full speed ahead, our engineering force was right on the job, and we picked up way at once. I looked down, and could see the points coming nearer and nearer. Closer they came, lunging as though they really wanted to get us, and it was a pretty tough job calculating our chances. Then, like a giant pair of calipers, the two points brushed our quarters as we shot ahead. My dear man, I was feeling limp when we got out of that, and that’s no lie.

Once in the open sea, and safely out of the nutcracker, we ran on down the line before a light northerly, giving Len a chance to make additional repairs on the clutch, which had taken a bad beating in the last few hours. We were all feeling good that we had come through the ice so well, when we might so easily have lost our schooner, and we went our way, keeping an eye on the edge of the ice on the chance that we might spot a bear or a seal. There is nothing gained by worrying over the accidents that have happened, or didn’t quite happen, and we had the future to occupy us, along that weather edge.

Dreadful loss of life and vessels in the days of sail and no power was caused on the weather edge. It is a nightmare to take a vessel through that heaving, tossing mass of potential destruction, especially when using the wind for propulsion. Any kind of craft could take an awful pounding from the sharp corners of the growlers, which would soon stave in the hull if the crew did not work hard and bring chunks of ice on their backs and drop them down between the sides of the vessel and the growlers. This work would go on for hours, until enough ice was thrown into the grinding maw to make a bed of soft slush ice that had the effect of a cushion protecting the craft’s bottom and sides.

Wooden fabrics stand up better than steel in this sort of thing, for the wood is more yielding. That is why it cost so much to repair a steel hull after working in the ice, especially after a voyage in the late spring, when the floes are old, washed out, and hard as granite, with no soft cushion of snow such as the early ice has. I remember that in 1912, with Paul Rainey in the Beothic, we struck heavy ice in Kane Basin, and as she was built of steel, we took an awful pummelling. Our contract stated that she was to be returned as we had taken her over, and I took her to Billy Todd, of Robbins drydock for a estimate. He told me the figure he was going to quote for putting her into such a shape as the contract provided, and I just stared at him.

“Have you ever had her on your dock,” I finally asked, “or one like her?”

“No,” he replied. “I never have. Why?”

“Well, sir, “I said, “she will have to have all the damaged frames, plates, and scantlings removed and rerolled, a lot of riveting done, and all in a prescribed time, subject to the approval of Lloyd’s surveyors.”

He gasped, and promptly doubled the amount of his bid for the work, and I believe he lost money at that. Yes, sir, these steel ships are expensive babies if you use them hard in ice navigation.

And the weather edge means using them hard. I can remember the hair-raising stories of Uncle Isaac Bartlett, Natty Percy, and others seeking shelter in the ice in a gale of wind, with heavy sea, thick snow, and frost. Under such conditions the edge is almost as bad as a rock-bound shore, but they had to take the chance of winning through to comparatively calm water. Growlers tossed by the heavy seas would gore their sides and bottoms like angry bulls. The only salvation lay in using all the wood and rope fenders the crew could make, and fixing up an ice bed. Perhaps despite all this she would be stove in and sink before anything could be done. There are many stories of brigs, brigantines, and topsail schooners, with crews from 24 to 50 men, last seen running for the weather edge of the ice, to founder there with all hands. I got caught in my first command, Father’s schooner Osprey, 41 years ago, and I remember it as though it was yesterday. I had a crew who had been through it before, and we got home with nothing worse than a broken rudder and a very leaky hull. We felt lucky to get home at all.

Anyway, the Morrissey had come through again, and we were on our way home in fog that kept us from looking for interesting things on the edge of the ice. You can find all sorts of things. Wood thrown overboard from a vessel anywhere between the Aleutians and Asia might come north with the Japanese current running up through the Bering Strait in the Arctic Ocean. Observations of this sort led Admiral Melville and Doctor Henry G. Bryant, president of the American Geographical Society of Philadelphia to release especially contrasted oak casks with heavy brass hoops, and containing position and date, in the Arctic Sea north of Alaska. Seven years later one was picked up off the north coast of Iceland and another off the Lofoten Islands, Norway. It was data of this sort, too, coupled with the wreckage of the Jeanette, that fired the imagination of Nansen, and resulted in the building of the Fram, with her historic drift in polar regions. What invaluable scientific information could be gleaned today from a drift across the Polar Basin to the North Atlantic! There is something I’d like to do!

In my logbook, for August 19 I wrote the following: “Saw the stars for the first time since reaching the coast of Iceland. Since then we have been in the land of the midnight sun.” And the next evening I received a radiogram from Tom Foley of the Western Union Company telling me that my father had died. I knew when I left home that it was only a matter of a little time, and I had been right. When he watched the Morrissey sail out of Brigus, it was farewell for good. But despite this knowledge, the final ending of his life threw a depression over me that held me for a long time. He was a good man, a great sailor and seal hunter.

On August 23, at 5:20 p.m., I stopped the schooner and ran the flag to half-mast. The bos’n stationed at the ship’s bell, and tolled it every two minutes. My brother Will, with Robert Dove and Jack Angel, my nephews, retired with me to my cabin, where I read the Ninetieth Psalm, the fifteenth chapter of the First Epistle of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Corinthians, and the fourteenth chapter of the Gospel according to Saint John. The Morrissey remained motionless from 5:20 to 8:00 p.m. in order to conform with the time of the funeral services at Brigus. Billy Pritchard, Len Gushue, George Richards, Joe Cowley, and Jim Dooling had all been at Turnavik or off sealing with Father, and most of their fathers before them, and they all talked about him as they sat on deck.

We then got underway and resumed our progress home. The water had changed from a dirty green and brownish colour to an azure blue. The colour of water is very much determined by the plankton content, and as I think I mentioned earlier, so is the presence or absence of fish. This I learned late in life, and I wish I had found it out earlier. The fisherman of the future, I am sure, will not go out and put down a cod trap in what has been a good berth with a prayed that Divine Providence will send the fish that way again. No, he will sail to what is reputedly a good place for fish, put down his thermometer, and tow net, examine his finds under a microscope, refer to his journals, and if he does not find the proper conditions, he will go on until he locates them, and has a reasonable certainty that he will get fish.

The point is that fish don’t just happen to be in some places and not in others, and the plankton content of the water is the great determining factor. In my early days of fishing, when we went out to haul the cod traps and the water was cold and clear, the ropes and twine were covered with slime, and we could see many fathoms down to the bottom, we called the water dirty and knew without hauling the traps that they would be empty. It did not occur to us that the traps were slimy because they were covered with algae, and that something was causing a deficiency of planktons which ordinarily would have kept the algae in check, and the whole cycle was accordingly upset. It may have been temperature or salinity. I don’t know.

I think that all this scientific work on the small forms of life found in the sea, with accurate data as to location, water temperature, coupled with stomach content findings of the cod and its prey, the caplin, herring, and squid, will eventually eliminate a lot of the chance which now attaches to the fisheries.

Many times I have cursed the unending fog. Every skipper has, not realizing that it was an inevitable natural reaction in the production of the rich fishing grounds of, say, the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. For at this point the warm southern stream, meeting with the ice-laden Arctic current, produces the fog. But more important, the southern waters, laden with rich plankton, and the northern currents, with their characteristic flora and fauna, on meeting produce a temperature in which neither can live. They die, sinking in vast quantities, and producing a rich food for the swarming life that has adapted itself to this temperature. It is on this life, the caplin, herring, and squid, that the codfish feed, and they come here to get it. The fishermen come here to get them.

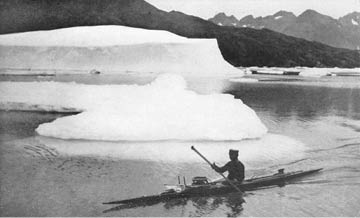

We were heading for Angmagssalik, in the fog as usual, when we broke into dazzling clear weather. The coastline, its great saw-toothed peaks standing out against a perfectly clear sky, and above that a narrow bank of golden cloud, which shaded into bars of deepening blue as it mounted into the heavens, were magnificent. There was a flat calm, and the play of colours on the water was breathtaking. The snow-capped peaks were lighted up by the blazing sun, and the glaciers running down to the sea like a great frothy streamers. I feel almost sacrilegious trying to describe it, but on all my years of travel I have never seen a sight that could even approximate its beauty. All hands were on deck, and for minutes at a time no one spoke, so impressive it was.

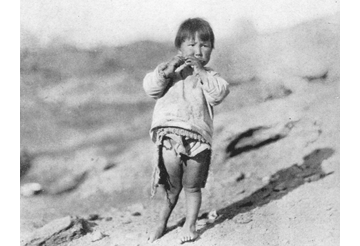

We made Angmagssalik all shipshape, and went to our anchorage of the year before. Our reception was warm, for we were old friends now, and we had a great time both ashore and afloat. Robert and Jack went into the fjords for birds and flowers, while I spent a pleasant afternoon getting flowers for our collection. I found bluebells such as are found in Scotland, patches of white cerastium and a number of Alpine flowers. Junius Bird arranged a dance here, everyone in the place took part, from the governor down to the smallest child. The governor started out dancing with his wife, to music furnished by the Morrissey’s gramophone, and then in turn with every girl present. He slighted none, and believe me, he was some dancer. The Eskimo women are born dancers and seem to have an inherent sense of rhythm. Some of our sailors showed them the quadrille, and after watching it once they went through it as though they had danced it all their lives. The Eskimos are musical, too. I have many times seen one of them get hold of an accordion, tinker with it a bit, and then make a good shot at reproducing the tune on a phonograph record they had heard.

As the party was winding up, we were treated to something that is fast dying out, a drum dance. I had not seen one for years, but it had lost one of its fascinations for me. An old man started it, slowly at first, but gradually warming up, bobbing up and down, chanting a wild and weird dirge, holding an improvised drum at arm’s length in front of him, and beating on it with ever increasing speed. The dance is a relic of pagan days, and the old man was carried right back into another time. He was no longer a Christian, but instead he was invoking the old gods. Perspiration ran off him in streams, his face was horribly contorted, and all of us were profoundly affected. No one said a word, and Pyrman Smith, ever on the job, made flare pictures of it that furnish a valuable record of a dying rite. Of course, in the old days the Angkok, or witch doctor, used to do the dance, and would go into a trance in which he would, in spirit, go all over the sky, and visit the stars. Pastor Rossing, who lives at Angmagssalik, probably doesn’t look with favour on things of this sort, but he knew we were interested, and didn’t stop it, for which we were grateful.

At the conclusion of the drum dance we boarded the Morrissey, and got underway the next day, Robert having returned with a very fine collection of flowers. We spent our time cleaning up the bird and flower collections, made the Smithsonian chests ready for shipment, and by dark had everything fixed up for the run to Brigus. We passed several bergs, big fellows, and these I reported to the Hydrographic Office at Washington, but apart from that there was little of interest or importance on the run home. We got to Brigus in fine shape, and tied up. It was a sad arrival for me, for it was the first time since I owned the Morrissey that Father hadn’t been at the dock to greet us.

We remained in Brigus for a day or so and then set out for New York, where we tied up on September 21, after an absence of four months and 22 days. On September 26, the gang went home and the Morrissey was laid up for another winter.