THE PEARY MEMORIAL, 1932

When Admiral Peary was taken with the illness that ultimately ended his life, he spent most of the summer lying in the sunshine on a muskox skin, spread on the lawn of his home on Eagle Island, Casco Bay, Maine. From there he could see a rough stone monument on Mark Island that was a range for the entrance to the ship channel. When a lad he had camped many times at the base of that monument, and I have no doubt that many of his happiest days were spent there. At any rate, it meant something real in his life, and he expressed the wish that a similar edifice be set upon his grave. When he died it was found that because of a law limiting the height of monuments in the National Cemetery at Arlington, this desire could not be fulfilled. But at Cape York, in the Arctic, a spot holding the deepest sentimental meaning for Mrs. Peary and her children, it might be done.

I saw Mrs. Edward Stafford, who was Marie Ahnighito Peary, daughter of the Admiral, and known as the Snow Baby because she was born not very far from the North Pole, when I returned from Greenland in 1931, and she told me that she and her mother had determined to carry out, as far as possible, the plans for a memorial. There is no one whom I hold in more reverence than Admiral Peary, and I promptly put the Morrissey at her disposal. She accepted the offer, and in January 1932, we began to raise subscriptions. This was necessary because of the Depression. Mrs. Peary had intended financing the whole project herself, but her income had been so curtailed that she was unable to do so. We thought that some of the explorer’s friends might help out, but they too had been severely pinched.

I lectured a few times, turning the proceeds over to the monument fund, and wrote many letters asking for assistance, but most of the letters went into waste baskets, and very few were answered. But there were those who did not fail us. Norcross had said that he wanted to take a run into Hudson Bay and Hudson Straits, with the possibility of an attempt to get through the Strait of Fury and Hecla, in the summer of 1932, but when I told him about what we wanted to do, he agreed to postpone his plans for a year and expressed a desire to go with us, doing some hunting while we were building the memorial. He helped us good and plenty financially, too, and that was a tremendous boost in ways reaching beyond what money could do.

Then the Standard Oil Company of New York gave us all the fuel oil, gasoline, coal oil, and lubricants we needed. Fred Strong, in Waukesha, Wisconsin, sent us vegetables of various sorts. The McWilliams shipyard trimmed down its bill, others gave us foodstuffs and clothing and a few contributed cheques. Their names are engraved on the tablet set in the monument. The lime, two tons of it, was given us, and it came well-packed and secured. That was more than could be said of the cement, which arrived in ordinary heavy paper bags that would leak if you looked crosswise at them. It was fortunate that the Morrissey was tight as a jar, so that no water could get at the cement, for it would have been bad news to get up north and find it spoiled.

With the material for the monument, and our other supplies, we had a big problem in stowing everything. We had to break open the cases and stow canned stuff in lockers and every available place. We were going to have many people aboard, including natives, and I wasn’t sure how much food to take. The regular ship’s company numbered 27, and they had their personal gear to take aboard. The materials for the monument, including lumber for the scaffolding, weighed 30 tons. And to top it all, we had a collection of animals. Before sailing from Staten Island, on June 15, we took aboard a registered Guernsey heifer, Dilwyn Beatrice, given us by Ruly and Mrs Carpenter, 40 white leghorn hens, given Mother by a friend in Chicago, several dozen goldfish for the Methodist minister in Brigus, two pigs that I got from a friend out in the Jersey meadows, and a cat, black as the Devil himself, given Junius Bird by Peggy McKelvey.

When the cat came aboard I heard Jim Dooling muttering to himself, and shooting hard glances at it. I asked him what the trouble was, and the gist of it was about as follows: “That God damned black cat . . . no luck this trip . . . cats and women . . . no luck . . . I wish I had my bag out of the Morrissey.” I laughed at him, and I kept right on laughing, for no one ever had better luck than we did on this cruise, proving the old superstitions wrong again.

As we backed out from the dock the Morrissey must have looked like Noah’s Ark, complete with cow, chickens, cat, pigs, fish, bundles of hay and straw. The mooing of Beatrice and the cackling of the hens didn’t seem to fit into an expedition off to the Arctic, but much we cared about that. Jim Dooling’s reference to women was to Mrs. Stafford, who with her two sons made the trip with us. Mrs. Peary and her brother, Mr. Diebitsch, saw us off, and as we steamed out into the bay I could almost hear him saying that it would be a fortunate thing if we ever saw Cape York. I’ll admit that the Morrissey was well down in the water, drawing 13 feet aft instead of the usual eleven and a half, and her decks were piled up with gear from the knightheads to the taffrail, but the schooner could stand it.

We made the run to Brigus in fine shape, and immediately proceeded to take aboard yet more gear. However, we put all the menagerie except the cat ashore. Beatrice had been off her feed at first, possibly due to the motion of the vessel, but we tried her on Quaker oats, and she went for them the way the advertisements say people do. Soon she had worked into eating her normal feed, which saved us money. However, she remained at Brigus, and that was one worry off our minds. Generally speaking, it has been my experience that life aboard the Morrissey, human and animal, doesn’t need much coaxing for chow.

While in Brigus, Mrs. Stafford met some of the Admiral’s old friends, including Lady Bowring, wife of Sir Edward Bowring. But the social side of our visit was of minor importance, for we had to remove our deckload and rearrange it. We took aboard 14,000 additional feet of lumber for the scaffolding, and on top of this we lashed the two whaleboats, 80 casks of diesel oil, 15 or 20 barrels of water, and the monument cap of Nirosta K2 metal, weighing 500 pounds. We also secured more iron and steel bars, hammers, sledges, and drills, while Fred W. Angel, a consulting engineer, told us not to go without a 10-horsepower gasoline engine for use in hauling building materials. We saw to it that one was put aboard. It crowned everything else, and completed our loading.

We put to sea on June 29, with the covering board amidships awash. The additional material had increased her draught to 13 feet 9 inches astern, and 8 feet 6 inches forward, which is about as far down as she could go unless we rerigged her as a submarine. But she would still foot. I had intended going up the Labrador coast, around the Iron Bound Islands, but fog shut down on us so we hauled offshore, passing the Domino and Batteau Land about 20 miles out. The wind freshened all the time, and we carried full sail despite our heavy deckload. The consequence was that the lee whaleboat had to be freed of water twice, while a lot of green seas smashed clean over us, forcing us to batten the hatches, skylights, and the forward scuttle. By noon of July 4, we had logged 840 miles in 120 hours, an average of about seven knots. One would have expected some water to come through the deck because of the heavy load, but not a drop got below, which spoke well for the workmanship that went into the Morrissey.

By the afternoon of July 6, we were close into the Sukkertoopen on the Greenland coast, having sighted a number of vessels, presumably French fishermen. The Frenchmen have been fishing here for the past few years. Formerly the sailing fleet left the coast of Brittany in March and went to the Newfoundland Banks. On July 8, we saw the sun for the first time since leaving the Funk Islands, and as there was no sea we had regular clean up day. We had such a crowd aboard that we were forced to rig cots in the saloon amidships, and the going had been unpleasant for a day or so, although there was no grumbling.

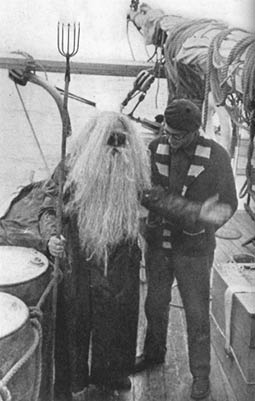

Jack Angel, second engineer and undergraduate in engineering at McGill University, got his gang started on the carpentry work, making sledges, water barrows, and rock barrows. This took some time, and occupied us while we were crossing Disko Fjord. An interlude was furnished when we crossed the Arctic Circle. It was late in the afternoon, foggy, and the damp dark clouds hung low overhead, when a deep bass voice was heard ordering us to stop. We did so, and Father Neptune, bearded with trident in hand, came over the bow, asking for the Stafford boys, Edward and Peary. But they had heard of his probable arrival, and had stowed away below, fearing he might take them away with him. I don’t know where they got that idea. Perhaps someone told them. At any rate, he ordered that they be brought before him, and they were soon rounded up. You can’t hide for long on a schooner the size of the Morrissey.

Blindfolded, they stood before Neptune, and he assured them that they would remain aboard, and then continued:

“About 50 years ago a young man came into the northern part of my domain for the first time on the whaler Eagle. I administered to him the same ritual that I shall presently give to you, his grandsons. And while you cannot, as he did, be the first to reach the northernmost tip of the world, the North Pole, you can be the same strong men, physically and mentally and morally, that he was. Life in my realm is often hard, but it is always just. The weak and poorly equipped fall, the strong and well-equipped have no fear. Your grandfather was of the latter group, and you, too, must be of it.”

Neptune then reached for a bucket full of some mixture, lathered the boys with it, and shaved them with a great blunt razor. This concluded the ceremonies and, removing their blindfolds, shaking hands with them, and wishing the Morrissey well, he disappeared over the bow.

Included in the Morrissey’s company were three members of the University of Michigan Expedition, headed by Professor Belknap, and we went to Upernivik to get permission to land them in the district. We arrived there on July 10, and Governor Otta, his wife and daughter, came aboard. Little did I realize, or did they, what the future held for them. It is usually a pretty good thing that we cannot see beyond the veil, and here was an instance of it, for dreadful tragedy hung over these three. Both Mrs. Otta and her daughter were counting the days before a boat arrived to take them to Copenhagen, where the girl was to be married to her betrothed. Everything looked promising, with great happiness ahead, but on my return to New York after completing our work at Cape York, I read the following dispatch in the newspapers:

“Copenhagen, October 22. Governor Lemboke-Otta of Upernivik, Greenland, and his wife and 18-year-old daughter are believed to have drowned in the sinking of the government schooner Saelen off the Greenland coast, the Greenland Board announced today. The Saelen left Upernivik, the northern colony in western Greenland, on September 26, and nothing has been heard from her since. The Saelen’s destination was Holstenborg, where she was to meet the regular steamer from Denmark.”

And the north had claimed more victims. Had the original plans prevailed and had the ship from Copenhagen visited Upernivik as arranged, the story would probably have had a different ending. But the planning was taken out of the Otta’s hands. Someone else threw the dice, and they were loaded. You can’t beat the game. If your number is up, it doesn’t matter how impossible it seems for circumstances to arrange themselves; it will happen. There’s no escape, whatever you do, or don’t do. Fatalism may be called the coward’s escape from reality, but it doesn’t seem that way to me.

But this tragedy lay in the future, and on the present occasion we had a delightful visit, with our guests obviously delighted to see new faces. The governor asked me if I would take two Greenlanders to the new station farther up the coast, at Kraulshavn, near the Devil’s Thumb, and this we were glad to do, and soon after they came over the side, and the governor and his family left us, we got underway. We worked our way up close to the Duck Islands, finding some loose ice, although not nearly as much as in other years. This scarcity of ice was a real break for us, and we made good time to Kraulshavn, where we put ashore the Greenlanders and Schmelling and Gardiner, of the Michigan party. Doctor Belknap remained with us to supervise the engineering work on the monument, and we laid our course direct for Cape York from the Devil’s Thumb, sailing over Melville Bay, and again encountering favourable ice conditions. We made the run in 42 hours, and but for fog we could have done it in 30. But we had no complaint, for had we run into bad ice, we might have equalled the record of the year before of being hung up for more than a month. We tied up to the glacier on the south side of the cape, and there we were, on location.

We went ashore as soon as we could get a boat away, to look over the ground and see what was what. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky, and the sun was so warm that water on the face of the glacier was waist-deep in places. We encountered a number of crevasses getting away from the edge, but no one fell in permanently. One or two members of the party slipped into them, but were yanked out again by the line binding us together. Once on land we untied, and some of the younger fellows went gaily ahead, determined to be at the top long before the old men. They laughed at the two Hiscock brothers, Gilbert and Reuben, as they trudged slowly along in their rubber boots. But the brothers had the last laugh. They were master stonecutters, had lived for years walking across Newfoundland in all seasons and conditions, and they knew what they were doing. Without ever hurrying or straining, they got to the top first, and as fresh as roses, while the youngsters’ tongues were hanging out. I don’t think most of us will forget that climb for a long time, for a month of being cooped up on the schooner had made us soft and tender. I’ll bet I lost five pounds of the fat Billy Pritchard put on us.

But we finally made the summit, and dropped anchor. The stone was suitable for our use, and there was plenty of water. But there was no sand for the cement, and we would have to go out and find some. We decided definitely on the site for the monument, and the next thing to do was to obtain dogs and Eskimos to help with the work. On returning to the schooner I learned from Junius Bird that there were only a few women and children and 35 dogs at the Eskimo village on the Cape, so I hove up anchor and steamed up to Thule to find out from Hans Neilson, the governor, where the Eskimos were and how many he was using, as this was the Polar year and the scientists were using the natives to build their stations. Fog closed down on us, and our three compasses each had a different idea as to where the north was, all of them wrong, due to the influence of the ore deposits in the Crimson Cliffs, but despite this we made Thule all shipshape, and through Hans Brunn explained to Neilson what we wanted after he had come out in the usual white clinker-built launch, with the flag of Denmark waving over him as he sat in the stern.

The governor and I were old friends – he and Netta, his wife, had come south with me on one of my previous trips – but he spoke no English and my Danish was no good, and Hans Brunn saved the situation. Through the interpreter I got the information I wanted, but we did not leave right away, as some work had to be done on the engine, and I told Len Gushue to go ahead with it, for we would be lying in an open roadstead while the monument was being built, and we might have to pull out at a moment’s notice if the glacier calved, or if the wind changed and brought the ice in. This gave us time to lunch with the governor and Netta. Their house was spotless, and the white linen, the fine old Danish crockery, and the beautiful service and arrangements would have done credit to the palace of the king at Copenhagen. Netta did herself proud, and I wish that Dan Streeter could have been there. Dan ever loved the good things of life, and he would have been in his element.

One Eskimo, Inughito, was at Thule, and him we took aboard, as head of the native group. He told me that Ootah, one of Peary’s own men, with several other families, was at Salvo Island, so I steamed as close to that point as the ice would permit. The Eskimos came out with their dog teams to greet us, and they were all there as we made a berth in the ice. A gale was blowing on shore, driving bergs down onto the weather edge of the ice, and we had to look alive. I recognized Ootah among the visitors, and after a look around to see that no bergs were within threatening distance, I ran to the rail to clasp his hand and welcome him to the Morrissey. When a man has risked his life with you, it means a lot to see him after a number of years, and I was very much moved by seeing this faithful follower of Peary again.

I don’t know how long it took him to tie up his dogs and come aboard. Perhaps about 10 minutes, and when he did come topside I walked across to the weather rail with him. I was so glad to see him that for a minute I didn’t look out to windward, but when I did I saw something that froze me to the deck. A big berg was sailing squarely into where we were, and chances were good that when it struck the ice it would crush the sheet and us along with it. I sang out to let go all lines, yelled for power, and ordered full speed astern. Too late . . . the berg was coming too fast, and escape was cut off. So we hooked her up ahead, trying to get as far into the ice as possible. Then the berg struck the sheet, and rolled, crushing the ice. Before we cold swing the main boom clear it was caught by the berg. It bent like a sapling in a hurricane, until the pressure was too great. Then it snapped six feet from the end. Our dory was hung in the stern davits, and I thought we were going to lose that too, so we let go the tackles and she went down all running, the Eskimos grabbing her as she hit the ice and hustling her clear.

In the meantime I ordered dynamite to blow off the lee corner of the ice, and also had all hands on the job with pokers and prizes to push the berg into open water. It looked hopeless, and yet the berg began to swing slowly away, as though it felt it had done enough. We backed the Morrissey until the broken end of the boom met the ice firmly, and helped the men. We worked up to full speed astern, and finally got that big mass of ice on the run, and then, when we could get out, worked clear ourselves. We were lucky, for that was too close for comfort, and believe me, sir, I wasn’t long in getting out of that berth into one less exposed.

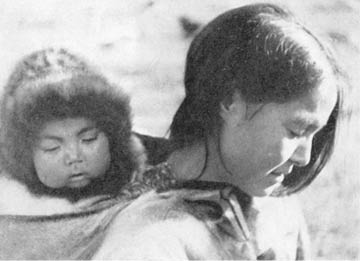

Then the Eskimos came aboard and I explained what we wanted. They were all for it, and they left in a hurry to get the rest of their crowd, their dogs, and belongings. It was all done very quickly. Two and half hours later after Ootah first came aboard we left with more than 100 dogs, 11 sledges, and 25 Eskimo men, women, and children, including a baby that was being born when we hove in sight. To make room for the dogs, we swung one of our boats out in the davits and built a pound where it had been. It was a very small pound, and the uproar was terrific, as all the dogs, as usual wanted to fight, and were telling the world all about how tough they were. Jim Dooling again came to the fore, and this time I heard him prayerfully remarking, “From dogs and guns, and women’s tongues, O Lord deliver me.”

With all this cargo aboard, we arrived back at the cape on Sunday afternoon, and anchored about 100 yards from the glacier, in about seven fathoms of water. We saw that several families of Eskimos from the Cape York village had set up their tupiks and were awaiting our arrival. The wind was blowing cold from the east, with sleet, and as we had strenuous times ahead of us, I ordered all hands to turn in and get some rest. The Eskimos were bedded down in the hold on top of the concrete. Consequently everyone was fresh and ready to go on the morning of July 18, a wonderfully clear day.

We got the two whaleboats over, lashing them together with scantling as a foundation, and sent the first load ashore. It consisted of the gear of Doctor Belknap, Wells, and Carswell, master masons, George Bartlett, carpenter, Paddy James, helper, and the Hiscock brothers, master stonecutters. The float made the shore all shipshape, and sledges were loaded and off on the five-mile climb to the top, where headquarters were to be established. The remainder of the day was spent in settling the crowd there as comfortably as possible. Clothing, sleeping bags and blankets, tents, cooking utensils, a stove, fuel, food were all taken up, and in addition Ed Weyer went up pulling a small sledge loaded with his cameras, so that he could make pictures of the whole thing from beginning.

Then we started in on the materials for the monument. The cement and lime came out of the hold in perfect condition, and by 9:00 p.m. were on shore. This ended our working day, and when Ootah came aboard with a note from Doctor Belknap that everything on shore was under control, I was mighty pleased, and gave the Eskimo women biscuits, coffee, tobacco, cigarettes, tea, sugar, and chocolates, and then, making the radio operator night watchman, ordered all hands to turn in. It came on to rain early the next day. I had told the crowd on the mountain to make themselves as comfortable as possible, but only the Hiscock brothers, their experience valuable to them, as experience always is, did a good job. When they set up their tents they put board floors under them, high enough to let the water pass under. The others regarded this as unnecessary, and as the result was uncomfortable for days thereafter. At an elevation of 1,500 feet one gets a lot of fog, mist, and rain, especially at Cape York, with so much water around and cold air from the ice cap aiding the precipitation.

But the sledges continued going up the mountain and I sent the whaleboats after sand. They found a good place, but every bit of it had to be screened, shovelled into bags, brought to the water’s edge, loaded into the boats, which were still lashed together, ferried three miles to the foot of the glacier, unloaded and carried to the edge of the ice, where it was put on the sledges and hauled up the mountain, to be dumped 50 yards from the site of the monument. This was done in a heavy rain that lasted all day, making things bad for the Eskimos, who had no oilskins or rubber boots, and it was pretty damp, too, for the crowd at the top under canvas. Belknap and Carswell came down in the evening to complain of leaky tents, so I sent up all the spare canvas I had, including the foresail. One big tent was rigged up, with walls of cement bags protected by boat covers and spare sails. Three oil stoves were brought ashore for the Eskimos, and two more were sent up the mountain, to dry things out a bit.

I could see that with the rain continually soaking the Eskimos’ gear, and with the steep start of 500 feet or so, the crowd would soon be played out, so I decided to use the engine intended for hoisting purposes at the foot of the monument, to get the sledges up the steep haul. It was accordingly taken ashore, and we were confronted with the problem of getting it up the mountain. Len and Junius thought it over, and concluded that the thing to do was to make the engine hoist itself. So they put it on a sledge, fastened a two-inch Colombian manila line to the nigger-head of the engine, ran it through a block fastened to rocks at the top of the sharp incline, and led it back to the engine. Then the drum was started turning, and it was wonderful to see that power plant pull itself up the grade. The leads would not come fair because there were two bends in the path and this necessitated the use of snatch blocks, which worked out successfully.

Once installed, the engine did its work beautifully, taking loads of nearly three-quarters of a ton up in fine shape. It was great to see how pleased the Eskimos were at not having to climb that steep grade anymore. They all had coughs, and undue exertion would bring on spells that were pitiful to behold. From this time on they were able to make three round trips a day with fairly good loads on the sledges. They could ride up and still keep the men busy at the top. This was useful when the sand was being taken up, for in all 1,140 bags were required.

The Morrissey was having troubles of her own at this time, as drift ice coming out of the fjord on the south side of Cape York kept filling up the bight in which we lay, and this was a big bother in getting sand to the landing. To make it worse the aftermath of the strong southerly wind was a tremendous swell that rolled in through the loose rubble of ice. The bottoms and sides of the whaleboats caught plenty of hell, for those chunks of ice were about as soft as paving blocks. But they were good boats, and they could take it, so work went on most of the time, except when the surf was too bad for them to land.

Norcross had been off hunting, and he came back aboard with a fine lot of birds and a seal or two for the mess. He brought sunshine with him, and we took full advantage of it. The constant rain and consequent crumbling of the side of the hill had destroyed the lower tip of the glacier, and we were forced to lug all materials 100 yards before they could be loaded on the sledges. So we moved everything possible to the first landing and made a pile of lumber, sand, lime, and cement there. It was an all-day job, but it meant a lot of future trouble avoided, and it was well worthwhile.

Early in the morning of July 25, Hans Neilson came alongside in his motorboat, with a badly cut thumb that needed attention. Our surgeon, Robert Dove, attended to this in quick time, and the governor then went ashore with me. I think he was surprised to see how well we had things organized. The set-up of the engine amused him, and he laughed heartily when he saw it pulling a sledge up the grade with nearly a ton of cement on it. I was glad, too, that he could see how we were handling the Eskimos, for it pleased him and he readily gave his permission to pick up a few more at Thule to help get walrus to replenish our meat supply.

Work on the monument was well enough in hand so that I could leave it, with Doctor Belknap and Inughito proving ideal heads, and I took the Morrissey to Thule again. We had thick fog all the way, but felt our way along to our destination, remaining just long enough to drop the governor and to pick up a few hunters. We kept the fog with us to the eastern end of Saunders Island, but once in clear weather we hooked her up and the next morning were steaming into Whale Sound. There wasn’t a ripple on the water, nor was any ice to be seen until we neared the end of Herbert Island. Then we began to see the bergs between it and Karnah shore.

We also sighted a small herd of walrus, and the kayaks were dropped overside. These Eskimos were keen, and in a short time the fellow nearest us harpooned one of the animals. We ran over, shot it, and took it aboard. By this time another was harpooned, a fine big bull, and we got him too. But this was too slow work, so we took the kayaks aboard and steamed over toward the Prudhue Land shore, coming across several herds on the ice. We stopped the schooner and waited for the sun to make them sleepy enough so that we could get within harpooning distance, and then put over the whaleboats, Norcross commanding one and I the other. In my boat were Mrs. Stafford and the two boys, the elder of whom had a 44.40 and did well with it. I had a .401 and did badly, shooting only three on the pan, when I should have had 10 before they all got off. Norcross with his heavy rifle killed 15 on one pan. In all we accounted for 31, and hoisted them aboard. I have never seen walrus so numerous and so quiet. They were badly sunburned, too, which is what happens to the old harp seals when they crawl out on the ice and cannot get back to the water again, due to the ice being rafted up in a gale of wind. In the Gulf of St. Lawrence I have heard seals actually yell when driven into the water, and I noticed that these walrus tried to climb out on the pans as soon as the salt water touched their hides.

With the walrus loaded we went back to Thule, where I landed our five hunters and seven walrus as payment for their work, and then we were off again for Cape York, arriving early on July 29. We had brought back 26 walrus, averaging about 1,600 pounds each, and every bit of meat could be used. As soon as our anchor struck bottom we started the work of landing this addition to our larder, and before the last one had gone over the side the mate had his men cleaning up the deck and paintwork. He hated to see a mess on board, and he wanted to have the Morrissey looking like a yacht all the time.

Belknap reported that they had had good weather all the time we were gone, and the monument was up eight feet. While we were away the glacier tongue had been almost totally destroyed, so it was lucky for us that we had moved everything up above the bad place. I had the Eskimos carry the fresh meat well back from the high water mark, as pieces of ice breaking off the glacier made small tidal waves and I had no desire to see our supplies washed out to sea. While work was going forward I spent most of my time on the beach, for here I was right in touch with everything, and I could handle things much better.

The Morrissey was getting tossed around pretty badly by the swell, which was rolled in by the stiff southeast breeze, but the wind died during the night. The swell remained, however, and the surf was too high for the whaleboats to land, and they were tied up astern. I did get all hands ashore, however, to help out with the work, some assisting the Eskimos in cutting up and moving the meat, and others screening and bagging sand. Junius went to the Cape to start his archaeological work on the oldest ruins there, doing this for the Heye Foundation.

I had only one real worry, and that was the calving of the glacier. This could be a serious matter if things broke wrong. I remember what happened on August 10. The Eskimo men with the sledges had gone up with the last load of the day. It was a clear, calm, bright afternoon, with the sun burning down on the face of the glacier. All the Eskimo women were busy drying out skins and sleeping robes. The air was full of millions of little auks winging back and forth, bringing food to their young, and above the whir of the wings you could hear the high, piping notes of the hungry ones, a noise ceasing only when the attentive parent shoved a nice juicy shrimp down the eager little throat. The sky was cloudless and the Morrissey lay like a black swan on the limpid water. I was on shore and the crew were lounging on the deck when we heard a sharp sound like a pistol shot from the direction of the glacier. It drew some of the Eskimo women out of their tupiks, but for five minutes nothing happened.

Then, as we watched, a small piece of ice fell from the glacier, to splash in the water, and as it hit, the entire face of the ice crashed down with a rush and a roar. When it came to the surface again that solid wall of ice was in a million pieces. A great wall of water was forced up, the surf receding from the shore. It broadened out as it approached, and it looked almost as though it was going to dry up where the Morrissey was anchored. The women were diving into their tupiks for things they valued as much as their lives, and then running up the hill toward me, bringing with them a sick Eskimo, who turned out all standing, minus his pants. The wave was on its way in now, and it was a dandy. It broke on the beach, rolling the meat over and over, uprooting the tents, and soaking everything.

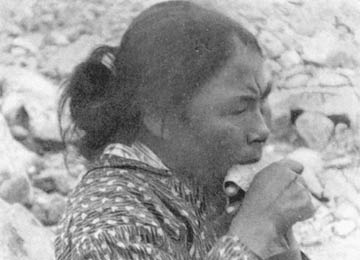

Not much was lost, as the boulders on the beach caught the stuff being swept out by the backwash, but the water put out all fires, overturned the cooking, flooded the tents, and in general made a terrible mess. When it was all over, and the water had receded, the young women just stood helpless, but the two old women in the party soon led the way down and were picking things up and getting fires started. These two were the old stand-bys who knew the ropes, and were always on the job when they were needed. Yes, sir, the strength and enthusiasm of young people are great things, but there are times when the steadiness and experience of older heads save the day.

Daily our troubles in landing sand and supplies at the beach were increasing. Sometimes we had to tie up the boats at the stern and wait for more favourable conditions. At other times we had to hold them just outside the surf line and throw the supplies overboard, to be pulled ashore. We lost a lot of stuff doing this. The ice from Melville Bay increased our difficulties, and we were also bothered greatly by snow, rain, and fog. I went up to the summit one day, and ran into the thickest fog I have ever seen. At the heaving off place you would never have guessed that there was a human being within 1,000 miles. Even sound was muffled. And yet, 150 feet away was the monument, with all the crowd working. It was cold, too, and everything was covered with frost. This included the men’s beards, and gave the youngest of them an appearance far beyond their ordinary life expectancy.

On August 15, Norcross, Robert Dove, and Joe Cowley came back from another hunting trip, and to judge from their stories, they had had a hot time. Their luck had been poor in hunting, collecting, and taking pictures. One of their aims was to get near enough to the bird loomeries to photograph them, but the surf was so high that they could not get within range. High winds with rain and snow had plagued them, too, but they were emphatic in saying that they wouldn’t trade their experience for anything. As I write this, word comes to me that Joe Cowley has slipped his cable. He was one of my best men, and I am going to miss him when I take the Morrissey north in the future. His place can be taken, but never filled.

The monument was now up 41 feet, and on August 16 we drew wonderful working conditions for a change. The last of the material had come up from the shore, and I watched the final steps toward the completion of the memorial. Words cannot express the depth of my feelings as I saw the two big marble P’s, one on the northeast and the other on the northwest face, transmuted from lines on a working drawing into actual fact. One corner of the monument pointed due north, to the Pole that Peary discovered, and the structure already looked impressive. It looked more so the next day, when it was finished, with the metal cap set in place and the scaffolding down. We were a happy crowd, for we had done our job for a man we loved, and we had done it in a month. The sledges brought down 1,200 feet of lumber while our crowd were busy getting their gear into the whaleboats and aboard the Morrissey.

This was finished up Thursday night, and Friday dawned clear and warm. But Mrs. Stafford did not think that Mrs. Peary would want the monument dedicated on a Friday, so we postponed that event until the next day, using the time cleaning things up on board and ashore. Norcross and Ed Weyer made pictures of the monument for those who had contributed, and without whose help we could never have put it over. In the late afternoon the whaleboats went off for fresh water, and took the two Eskimos who lived at the Danish station to their homes. Before they went I gave them food, blankets, and kerosene oil in payment for their work.

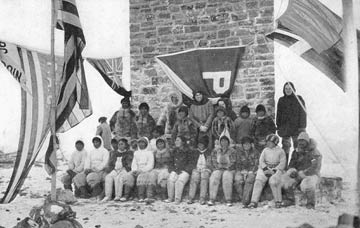

Saturday, selected for the dedication because of that old sea superstition that Friday is unlucky, a belief so strong that for many years no vessel would sail on that day, proved to be impossible, with snow and high wind, but Sunday was perfect for our purposes. Early in the morning I went ashore with Harold Batten and Ed Weyer, taking the flags for the ceremony along with all of Ed’s camera equipment. The rest of the crowd came at 10:30 a.m., and when they arrived everything was ready. The American flag was in the centre, flanked by the English and Danish ensigns, out of deference to the crew in the former case, and because we were on Danish soil in the latter. There were also the flags of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, the Explorers’ Club, Bowdoin, the Society of Women Geographers, Kean Masonic Lodge 254, and the Peary Arctic Club. The Admiral’s own private signal covered the tablet.

At the base of the monument were grouped Mrs. Stafford, her two boys, Doctor Belknap, Ootah, and myself. Mrs. Stafford spoke first, telling why the monument had been built here, in much the same words as I used at the beginning of this chapter. Then she thanked my men and the Eskimos for their work and achievement. I spoke next, and expressed my gratification at the part Newfoundlanders had played in the actual building of the memorial, because Peary had always gone to Newfoundland for his men. I told Ootah that we were handing the monument over to the care of his people, and appointed him to see to it that they knew the whole story of how and why the edifice was built, and to make sure that the tale was passed on from generation to generation.

When I had finished, Mrs. Stafford unveiled the tablet, and we made pictures of the construction gang and Eskimos at the base. The latter were all dressed up in their best furs, and the whole thing made a great tableau. Our work was ended, and we made our way back to the schooner. I thanked God that I had been able to help give the world a definite memorial to a man I had loved and served.

A heavy sea was running as we returned to the Morrissey, but the sole casualty was a crushed finger suffered by one of the Eskimo children. He never let out one whimper, then, or while it was being dressed. As soon as the boat in charge of Joe Cowley and the mate, which I had sent to Junius’ camp with supplies, returned, we hove up anchor and started off to hunt walrus and to visit several villages farther north. Mrs. Stafford had made several trips up there with her parents while a child, and wanted to see them again. Ootah, Inughito, Kesuk, Poodloona, and Nipsangwah were our hunters, and they were all good men.

On August 23, we hove up off Kangardlooksoah and sent the whaleboat ashore. It returned with all the natives who could pile in, and the rest came out in kayaks for coffee and biscuits. They were a fine crowd, and it was like old times to see the care they took of the children’s clothes, which were of fur, trimmed with white fox. The little caps had the fox ears left on, and gave the kids an impish appearance that was very amusing to see. Our next stop was Falcon Harbor in Bowdoin Bay, where Peary had built Anniversary Lodge in 1893, and where, on September 12 of that year, Marie Ahnighito Peary Stafford was born. It was a great thrill for her to return to her birthplace and show it to her sons. They went ashore and picked up some interesting souvenirs.

We then sailed past what Peary had called “the sculptured cliffs of Karnah.” “They are interrupted,” he wrote, “by a single glacier in a distance of eight miles, and are carved by the resistless Arctic elements into turrets, bastions, huge amphitheatres, and colossal statues of men and animals.” We anchored at Karnah, and Ootah’s mother came aboard with her grandson, a handsome Eskimo, taller than average, his new kamiks, clean new nanookees and his cloth parka testifying to his prowess as a hunter. Ootah proudly presented his son to me. He was the only one left out of five, the others having been killed in the hunt.

We also visited Peary’s quarters, Redcliffe House, on the point of McCormack Bay, where he wintered with Mrs. Peary in 1892. There was hardly a trace of the old place left 40 years later. Then we steamed over to Igoodiowny, but found the natives sick there, with five deaths already, and we did not land. When Mrs. Stafford was in the Arctic as a child her playmate was Kudlookto, and she had been looking forward to seeing him again, but he died the morning the Morrissey put in at Igoodiowny. She had heard he was there, and news of his death was a shock to her. Poor old Ootah felt it very keenly, too, as it meant that another link with the old Peary days was gone.

After this disappointment we cruised around a little more, but bad weather forced us to abandon the walrus hunt, and we bore up for Thule, where Hans Neilson entertained us again, and royally, too. Inughito left us here, and I was sorry to see him go, for he had been of tremendous assistance to me. Without his guiding hand over the Eskimos, I don’t know what we would have done. I gave him a lot of stuff for his work, and then we returned to Cape York, where Junius came off and we paid the Eskimos still on board. We didn’t worry about the price and there was no haggling. We just divided all our spare supplies up, and this is the sort of thing they received: lumber, tools, sledges, oil barrels, rifles, ammunition, foodstuffs, milk, sugar, corned beef, cocoa, tea, coffee, chocolate, biscuits, candy, cheese, cigarettes, tobacco, and blankets. All along we had given them presents, beads for their women, tools such as files and drills, and now we did not stint them anything they wanted. All of them had been wonderful in their work, and they made the monument possible.

With this all settled, we took the last of our Eskimos to Kerkotak, the ones who came aboard when our main boom got smashed up by that wandering berg. They had left their homes in a hurry, leaving the dogs to fetch for themselves, and what the animals had done to the skin summer tupiks was a shame. There was one amusing incident in connection with this, too. Eskimos keep their meat in caches of rocks build in a circle with a base diameter of about seven feet each, and piled conically to a height of seven or eight feet. This protects the food from the dogs. In some way a puppy had found his way into one of these examples of canine paradise. Perhaps he was thrown up there by an Eskimo to get a square meal, and had been forgotten in the excitement of leaving. Whatever the cause, there he was, and when the Eskimos returned he had eaten his way practically to the bottom of the cache. He was so fat he could not walk, and I can’t even guess how much meat he had consumed.

Anyway, we got a good laugh out of it before saying goodbye, and steaming across from Melville Bay, getting our last glimpse of the monument, with the late gleams of the sun reflected on its metal cap. Our first port of call was Kraulshavn, where we dropped Professor Belknap at the Michigan camp. Schmelling and Gardiner looked fit after their summer, although they reported that this was a terrible place for wind, which went as high as 76 miles an hour and usually blew about 40. We gave the party two loads of lumber and two full boxes of dynamite with detonators for sounding the inland ice, wished them luck, and steamed on. Soon they were lost to sight behind a bend in the fjord. Their plans were to make meteorological and geological observations, and they hoped to cross the Greenland ice cap the following spring.

Hans Brunn left us at Godhaven, where we visited Doctor Porsild, head of the Danish Arctic Station there. I said goodbye to Hans, and it was the last time I ever saw him. Since we had first met in the spring of 1930 I had come to like him more and more, and it was a great shock to read of his death after a short illness some time after returning home. Hans had inherited a great fortune, lost it, and dropped out of sight while still a young man. In that period he came into contact with Knud Rasmussen, and he was next heard from in the Arctic. After a number of years in Greenland he went back to Denmark and bought a small farm. He was demonstrating that he could work his way up again when he was taken fatally ill. But that too lay in the future.

Although I have made no mention of it in this chapter, we never gave up our habit of dropping drift bottles overboard and on the way back to Brigus we threw one in at latitude 48”35’ North, longitude 52”50’ West. It was recovered near Solvaer, Norway, on January 13, 1934, at latitude 6”35’ North, longitude 12”12’ East, after a drift of more than 2,800 miles. The Morrissey stopped briefly at Brigus, dropped off Mrs. Stafford, her two boys, and Louis Frizzel at Eagle Island, Maine, and came down to City Island, whence we steamed to the McWilliams yard. Our job was done, and so was the Peary Memorial Expedition of 1932.