THE STRAIT OF FURY AND HECLA, 1933

In the early part of the nineteenth century – (I quote from an article written by Arthur D. Norcross for the New York Times) – England sent many expeditions into Arctic America to search for the Northwest Passage, then thought to be the key to Far Eastern trade. These expeditions carried with them such famous explorers as Ross, Franklin, and Parry. After Parry’s first voyage, 1819-20, in which he penetrated nearly 30 degrees of longitude, beyond the point reached by any navigator, discovering many new lands, islands and bays, no hesitation was felt about sending out another expedition.

“Parry commanded this new expedition and sailed aboard the Fury. ‘At daylight of the 8th of May, 1821,’ reads the journal of Captain Lyon, second in command aboard the Hecla, ‘His Majesty’s ships Fury and Hecla, accompanied by the Nautilus, transport, carrying stores, weighed and stood out from the Little Nore.’ The expedition selected the most treacherous region for the effort to discover the Northwest Passage. The course led through Hudson Strait, Frozen Strait, and Foxe Basin. These areas presented tremendous ice hazards, and still do today, being practically closed to navigation 11 months out of 12.

“Only by studying the task of the Fury and Hecla can one estimate justly the obstacles encountered and the difficulties overcome by their successful passage through the Frozen Strait to Repulse Bay and back again into Foxe Basin. The navigation of Parry and Lyon was superb. Their skill and courage took them by sail alone even further than vessels equipped with steam engines or diesel motors can go today. Moreover, they made accurate charts of their discoveries, and the important question of food was worked out in such a practical manner that they were able to prevent an outbreak of scurvy – always a menace to polar explorers.

“The Foxe Basin region is not very far north. In fact, Frozen Strait is slightly below the Arctic Circle. Nevertheless, because of tremendous tides and heavy pack ice which is never carried away by wind or current, this area is more difficult than the Lancaster Sound route, further north, where Parry had previously nearly completed the Northwest Passage. In its first summer the Fury and Hecla expedition withstood many hardships. Morale was exceedingly high. The men wintered at Winter Island on the southeast coast of Melville Peninsula directly under the shadow of the Arctic Circle.

“On one of Captain Lyon’s winter land journeys James Pringle, a seaman of the Hecla, fell desperately ill in the snow and was sledged back to the ship. Having apparently overcome his sickness he went aloft the next day to work in the rigging, and fell to his death. He was buried on Winter Island and in the spring a slab of limestone was placed on his grave.

“Before leaving their winter quarters for further exploration the men painted the names of the Fury and Hecla on the cliffs at South East Hill, now called Cape Fisher. Sailing northward, still under extremely difficult ice conditions, the expedition discovered Barrow River and soon afterward came to a narrow strait leading westward. There the entire summer was spent in an endeavour to pass through. Every effort met with failure, and the expedition wintered this time at Igloolik, at the entrance. The vessels returned to England the following summer.

“The narrow strait is now called Fury and Hecla Strait, and it still remains to be navigated; no one has ever passed through it with a vessel. Its name is an everlasting tribute to the courage and ability of the English explorers.”

As I have said, it was my intention in 1932 to take the Morrissey into the waters in which Parry and Lyon had sailed with their staunch vessels. Norcross had wanted to go before, and now he co-operated generously to make the trip possible. In 1927 I had taken the Morrissey to the southern and eastern parts of Foxe Basin and almost to the strait, but had done no collecting in the northern part. The National Museum wanted some specimens, and in addition we were to do work for the American Museum of Natural History, the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, the American Geographical Society, and the Navy Department at Washington.

It has been my privilege for 10 years past to work in co-operation with the Smithsonian Institute in furthering scientific studies of the forms of animal and plant life in Arctic lands and waters, and their zoogeographic distribution. Rich collections have been made of marine life, largely invertebrate, comprising decapod crustaceans, amphipods, isopods, barnacles, copepods, alcyonarians, worms, foraminifera, other bottom organisms and deposits, molluscs; also fish, birds, and small mammals. Algae and terrestrial groups have been collected, and also insects. I hope to continue this work for a long time, for it means much to me.

Before we left, Doctor Waldo L. Schmitt, curator of marine invertebrates of the United States National Museum saw to it that the collecting equipment was in proper shape. He has for years been my inspiration in this work, and under his guidance and his enthusiasm I am becoming more and more interested and enlightened in the work and care of the collection. No one knows but myself the great thrill I get when the dredge comes up, and its contents are spread on deck, or on the floe ice. Who can tell what valuable additions may be found in it, what priceless specimens? That is the fascination of it, and it grips you.

When we left New York, early in June, we hadn’t made up our minds whether we would go to northwest Greenland and then cross the north water to Ellesmere Land and coast down to Lancaster Sound and run through Prince Regent Sound, tackling the Strait of Fury and Hecla from the north, or follow the same road the Fury and Hecla themselves took. But anyway, we were off for Brigus, carrying a lovely little Jersey cow given me by Mrs. Sarre, genial hostess of Yama Farms, new spars from Seattle shipped east by Captain Roger Williams and, thanks to Mr. Davis, president of the road, put in place by the crane in the Lackawanna yards at Hoboken, a disc harrow from Tommy Robert’s Connecticut farm, some chickens I had bought, and two more pigs from my friend of the Jersey meadows.

After a fine trip we tied up at Brigus, and I found that someone in London had discovered, after all these years, that the Morrissey, of Newfoundland registry, was owned by an American. Prior to this time neither the customs officials in New York nor the British consulate had bothered me, but now it had to be seen to. The schooner had originally been American, so I went to the American consul at St. John’s and he telegraphed to Washington to see what could be done. I had a definite feeling that trouble lay ahead, but much to my surprise word came through in a few hours that everything was all right, and that the registry could be changed. It was a lot of work to have her resurveyed, but this was done, too. I was a little superstitious about the change from Brigus to New York as home port, but this proved to be groundless. We needed plenty of luck to bring the Morrissey back from that 1933 cruise.

Norcross and friend named Dillon joined us at Brigus, and we got underway just after midnight on July 4, about two feet lighter in the water than we had been the year before when we hove up anchor. We had fog in the Strait of Belle Isle, fog as dense and black as the smudge of a prairie fire. But this burned off, and we got wind squalls in its place. One put us down almost on our beam ends, and the jib sheet let go. We put her before the wind and doused the sail, which was badly torn up. And when this was all straightened out a leak developed in the new sleeve of the propeller shaft. It gave us great concern at first, but as the voyage went on we saw that it didn’t get any worse. At least, it didn’t until near the end of the cruise.

We kept on working north, and met the ice and fog as we hauled in for Indian Harbour. Our first narrow escape of the trip came here. I had anchored in Split Knife, but fearing the wind might veer to the northeast I hove up and steamed through the Cockade Tickle. The wind was freshening fast, so I kept going north until I could see that the bight of open water in which we were sailing was closing up. It was up to us to crack on full speed and try to get out of there before we were locked in, and we snored along to the eastward with everything we had. It was a close thing, and we had just cleared when the ice struck the land between Bears and the Cutthroat shore.

Once in the loose ice we steamed squarely off the land, finally reached the outer edge and stood on a compass course of north by east, with Bulldog Island abeam six miles off. We had fog, ice, a big swell, and little clear weather all the way to Hopedale, where I took Tom Winter aboard. He is one of the old stand-bys, and while I know the runs fairly well, I always feel more comfortable when old Tom is aboard as pilot. Knowing the inside passage enables one to manoeuvre a vessel through the narrow lanes and thoroughfares with ease, safety, and comfort. It is the same road that Doctor Grenfell travels in his mercy ship Stratchona.

I have mentioned it before, but I want to repeat here, as it cannot be too often repeated, that Labrador can never hope to repay the debt it owes this great man. The work he has done there will endure long after he is gone, and debt owed him will grow with compound interest as the years pass.

We were at Hopedale long enough to spend a pleasant hour or so with my friend Doctor Perrett, the Moravian missionary there, and his wife, and then we were off to the Farmyard Islands and Saddle Island, off Mugford. I was surprised to see very few birds and seals. The ice, however, was waiting for us, and we met it between the Saddle Islands and the Nanuktuks. Near the White Handkerchief we encountered walrus, and photographed them to our hearts’ content. They were without exception the quietest walrus I have ever seen, more so than those of 1932.

And by July 26, we had managed to get the Morrissey into another dangerous position. Strong currents hurled the ice in all directions, and the weird noises of the moving blocks made the night hideous. There was more to it than the noise, for our little schooner was in a bad spot. We worked all night to keep her from being stove in; all night, during which she was rolled around like a ball on a billiard table. Sharp corners of the floes tore at our rudder post and propeller. Others crashed against the sheathing of our hull, and again I thanked God for that staunch greenheart. At 3:00 a.m. we ran into an open lead, and thought we were all right, but it quickly closed up, and we were caught again. Then, when we were beginning to doubt whether the Morrissey could stand the gaff, it opened up. And all the time we had wind and dense fog, and our compass was behaving badly. What saved us was the fact that the fog lifted on July 27 so that we could see the old, heavy, dirty ice from Foxe Basin, and we ran over to Southampton Island to avoid it. This move proved sound, and we had no more trouble running to Coral Harbour.

The Hudson Bay Company’s launch came off and Sam Ford, the local agent, Robert Renny, his assistant, and Father Massie, the Catholic priest there, breakfasted with us. Junius Bird, Bob Moe, and Jack Angel, with several natives, left for Bear Island to do some archaeological work and some surveying, while Norcross went hunting. While they were gone I sent the dory ashore to fill the water barrels and after several trips our tanks were filled. We also filled our fuel tanks, transferring from the deck supply. Junius and his crowd were away for more than six hours, and Norcross didn’t come back until early the next day. The birds he was after proved to be far away, and scarce at that.

On Sunday we pulled into Bear Island, seeing the natives there in their best clothes, singing hymns. We did not stop long, but proceeded to Neakuktoktuyok, the Place of Skulls. Harry Gibbons, one of the Hudson Bay Company employees, told us the story of this place. There was a village there, inhabited by members of two tribes, the Iuvuliks and the Baffin Islanders. One day a bear appeared near the village, and all the hunters went after it. After it was killed a quarrel arose as to the ownership of the carcass. They fought it out to the death, and when it seemed as though all would be killed outright or fatally wounded, one of them sent his young boy to the village to warn his mother to flee. The youth obeyed, and when he had gotten her safely away told the other women what had happened. They took up the fight and everyone of them was killed, leaving the mother and her son as the only survivors. None of the Eskimo can remember how long ago this happened, and they always shun the place, but eight human skulls on the ground testify to the story’s truth.

Junius did some digging here, while the Norcross party made pictures, I did some dredging from the whaleboat, while Robert Dove remained aboard to skin some of the birds collected earlier in the day. We hove up anchor early the next day and steamed toward Cape Kendall. Our plankton net was kept busy and it brought up many interesting specimens before we landed again at Manico Point. This time Norcross and his party had good luck, although they reported difficult working conditions, walking through sticky mud and surrounded by billions of hungry mosquitoes. Photographs of members of the party showed them to be covered with the pests so that they looked like Negroes.

Consequently they were not sorry to leave, and using the lead constantly, we worked across the mouth of Roe’s Welcome, continuing on past Wager Inlet to Cape Frigid. Weather conditions were ideal, with clear skies and warm, bright sunshine, and I made an attempt to get through Frozen Strait. But the ice was too bad, and drove us back to White Island. We caught rain and wind here, but they only lasted for a day, and we put to sea again, only to be forced again by the ice to retreat back through the strait and north toward Repulse Bay. After various encounters with the ice we finally reached a good anchorage in Duckett’s Cove.

The Norcross party went ashore to see if they could locate a gyrfalcon’s nest and collect birds, while Jack Angel and Junius also went along, the former for topographical work and the latter to see if he could locate any Eskimo ruins. He reported no signs of recent occupation, but found many tent rings and a grave or two. I added greatly to the marine invertebrate collection with the dredge and plankton net. The ice damaged one of my whaleboats while all this was going on, but Junius and Jack did a splendid repair job, putting on a new keel and skeg to protect the propeller. The cove packed full of ice that night, and the Norcross party were forced to drag their boat over it to the schooner, which was quite a job.

When we got underway again I took another look at Frozen Strait, but it was still far from encouraging, so I resolved to try to work through Hurd Channel and get through Lyon Inlet to Winter Island and on over the Fury and Hecla route. There were times when I had a good mind to retreat back through the Welcome and go north after reaching the east side of Foxe Channel to Cape Dorchester and from there west to Melville Peninsula around Cape Penhryn. I had done that in 1927, but I recalled that Parry and Lyon had never given up in their efforts to go through, and with such a noble example to inspire us, there was nothing for it but to do as they did.

We had favourable weather, and toward the end of August, when we thought we could not get farther north, the ice began to move, and we were able to squeeze along. There were times when our keel was too near bottom for comfort, and the dynamite given us by Ruly Carpenter, who was a vice-president of the Du Pont Company, was used to great advantage in blowing up the ice ahead of us. Once we worked into a sort of cul-de-sac on the high spring tides. August seems a funny time to have spring tides, but that is when you get them in these regions. The only way of escape was to go over a bar, the heavy ice from Frozen Strait having blocked the entrance we had used. If we missed this tide we would have to wait an entire year to get the Morrissey out, and that wouldn’t have been so good. The ice kept coming in, and we had to blow our way even to reach the bar. It was a two-day job, and we used a lot of dynamite. By God, sir, you can believe me when I say that it was a grand relief when we finally slid into deep water. Once cleared, we worked into Winter Harbour, where the Fury and Hecla wintered in 1821-22. What we did there is really Norcross’s yarn, and it is better to let him tell it in his own words. I quote once more from his Times article:

“Because the ice at this point was pressing close on shore we were able to remain but a short time. But we organized a small shore party, landing in spite of rafted ice. Here we spent a day in search of traces of the winter quarters of the Fury and Hecla.

“Every foot of ground was studied carefully. No trace could be seen of the ships’ names that had been painted on the cliffs. However, late in the afternoon, when it seemed as if our task would be fruitless, we stumbled upon something strange – a large hole surrounded by a wall of rocks. Investigation among this accumulation of broken rocks revealed the tombstone of James Pringle.

“The stone and its inscription were in perfect condition, despite many storms and years. We were deeply stirred as we surveyed in silence the wreckage of this grave. It was difficult to understand why this hero of the north could not have been permitted to rest in peace where his comrades laid him in 1822. Such vandalism amid vast stretches of snow and ice seemed unbelievable. The Eskimos could not have been responsible, for although treasures are buried with their own dead, their respect for a grave is stronger than greed or curiosity. There is a possibility that unprincipled whalers, straying this far north, may have been the violators.

“At the risk of adverse ice conditions – for delay meant that the ice was fast closing in on us and there was danger of being marooned all winter – we determined to rebuild the grave of James Pringle. With the help of half a dozen men from the Morrissey we fashioned a monument 18 feet long, 12 feet wide, and seven feet high. This monument faces the sea and the original tombstone is placed in the front, set back and sheltered by a rock to prevent weathering.

“By midnight our task had been completed. We could go now, leaving behind a permanent memorial to James Pringle. Standing by for one memorable moment, we paid tribute where a century before another group of explorers had paid homage to a lost shipmate.”

When Norcross and his crowd finished this job, we got underway again, and on August 15 spotted a polar bear. We lassoed him, and a great struggle ensued. We kept him on the line for an hour, but he finally got away, and it is hard to say whether we or the bear felt more relieved by it. The Morrissey’s rail still bears the toothmarks of the last bear we had brought aboard alive. The episode reminded me of the time, 23 years before, to the day, when with Paul Rainey on the Beothic in the mouth of Jone’s Sound, I lassoed and captured Silver King, who was in the Bronx Zoo for 20 years.

Silver King was first seen on an ice floe. Using the bow of the Beothic, we cut off the point of the floe on which he was, and pushed it seaward. We got a one-inch manila line around his shoulders, but when it sagged he reached it and bit it in two. We tried again, and this time held the strain so that he could not get at the hemp, hoisting him aboard and lowering him into the empty forward hold. Later we made a cage for him, and he ultimately ended up in the zoo. Doctor Ditmars came to City Island to get him, and as I remember gave him about eight pounds of chloroform before he was ready and willing to travel.

Lyon Inlet filled up with ice while we were building the Pringle monument, cutting off our retreat to Murray Harbour. I might say here that going up the eastern shore of the Melville Peninsula at this time is unusually difficult because the ice in the southward movement through Foxe Basin and Channel constantly impinges on that shore. It looked pretty dubious to me, as I sat in the crow’s nest, and I knew we were in a jam. Will Bartlett, my brother, who knows more about ice than any man living, and who handles the Morrissey more tenderly and skillfully than I do, echoed my thought when he sang out, “Gosh, Skipper, I wonder how we are going to get out of this place.”

And just about as he said it, the current began to run, and things began happening so thick and fast that we never had a chance to wonder what was going to happen. The ice arrived promptly, and it reminded me of a traffic jam when you want to catch a train out of Pennsylvania Station, and offer the driver an extra dollar to get you there in time. We handled the Morrissey about the same way that a chauffeur would handle his cab, except that we had no lights to help us. Ice was all around us, buffeted us, pushed us around, rolled us. We worked our way as best we could, taking such leads as offered, avoiding as many wallops as we could, easing others. It was a wild ride, all right, and I can still mystify myself by speculating as to how we ever won through to open water. It was much too breathtaking for any consideration, or planning ahead. We did what seemed best at one minute, and let the next take care of itself, and by keeping this up for a whole lot of minutes we did make the grade, and resumed progress toward the Strait of Fury and Hecla, hoping that the wind would keep the ice away from us and not put us on the beach.

Parry describes the falls of the Barrow River, a place where his men found rocky dells and flower-strewn banks after months of snow, ice, storms, gales, and all that. We put in there, but arrived late in the season, and the flowers were all gone, while the river was pretty well dried up. The falls are 90 feet high and 146 feet wide, and our pictures showed quite a respectable volume of water rushing over them, although it was nothing like what it must have been in the spring.

The ice followed us here, too, coming in quickly, and we had to cut and run, despite the fact that our whaleboat was on shore. I had broken out the recall signal, but night was coming on and I was worried. The lane of water between the incoming wall of ice and the land narrowed as we steamed along, and we couldn’t even slow down to use the lead. We just had to chance it, full speed ahead. If we hit anything, it would be just too bad, but if we didn’t open her up wide, we’d last about as long as a cigarette. So we took the bad odds against the certainty of disaster, and we got away with it, working into a hole of open water.

I put up starshells for the whaleboat. I know that if the crowd remained in the Eskimo village on shore they would be all right, but if they tried to follow us, they might get into trouble. There wasn’t much danger of losing their lives, but they might easily lose the boat, and such craft are indispensable for work from a small schooner in the Arctic. In addition, they are a form of life insurance. For instance, should we lose our propeller, or break a shaft, the two powerboats could tow us in moderate weather. Or if we lost the schooner, could take to them. My men are sealers and fishermen and know how to handle small boats in ice and all kinds of weather, and we could probably get home safely in them. And so I did a lot of worrying about what would happen, only to see a signal flash half an hour later, and in a few more minutes the motorboat arrived alongside, in good condition.

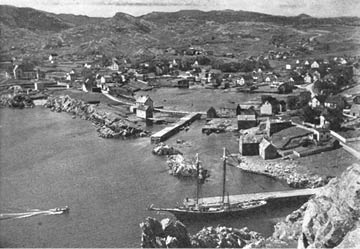

After this close shave, we kept on working past Cape Penhryn, and at length won through to the island of Igloolik, where the Fury and Hecla wintered in 1822-23. We found no one in the harbour or on the island, although we discovered the ruins of 25 or 30 old Eskimo winter houses. Of the Fury and Hecla there was but one trace, an old clay pipe that must have been smoked by one of her men. And now we were at the entrance to the strait, and we steamed on in. We had made good progress by sunset, which was a magnificent spectacle, with marvellous colouring. The kah-kah-kah of the red-throated loon and the splash of an occasional piece of disintegrating ice were the only sounds. The ice was coming out with the ebb tide, and the strings were wide and closely packed. I could see beyond it to the unbroken fields of ice ahead of us, just as Parry and Lyon had a century before, and I knew right then that we weren’t going to get through. We might as well try to take the Morrissey overland, and I figured that we could do more valuable work by returning to Igloolik for further collecting.

I put all our men ashore with Junius when we were back there, and they made a good showing in a place where I think archaeological research has seldom if ever been made. Later, when the material we found was passed over to the Museum of the American Indian, the director, George G. Heye, told me he was pleased beyond words with the specimens brought back. We also made many hauls there with the dredge, and the findings have gone to Doctor Schmitt, and are being classified.

We found some Eskimos here. They were having an excellent hunting year, with plenty of walrus, seal, and some narwhal, and at this time they were catching salmon and trout in the big river near the village. Like ourselves, the Eskimos do not require the same amount of meat in the summer as in the winter, and they live largely upon fish because it is easier to get. Later, when autumn comes, they stock up with walrus meat and blubber for food, light, and heat. Caribou is plentiful, and the fat is used for food, while the sinew affords them sewing materials for clothes and shoes, which are made from the skins of fawns and yearlings.

The Eskimos living in this section were much better off than any others I have found. They are free of all tubercular trouble, and are healthy and strong. The children look well, and have plenty to eat and to wear. For one thing, these Eskimos have no desire for white men’s weapons to get their game, and this keeps up their initiative and makes them able to handle any emergency. All in all, it is the happiest recollection of the natives I have had since the days of my youth.

But it was now high time for us to be getting out of here, and we started off in a light easterly. The current carried us into shallow water, and when the wind made up, with snow flurries, the sea kicked up quickly, being very steep, like the Great Lakes in bad weather. We were making eight or nine knots under sail, and snoring along. We could not yet trust our compass, and we steered by the direction of the wind and by our thermometers. When the mercury went down we knew we were getting near the ice, and sheared off. Thanks to our experience in 1927 I knew pretty well how to work things, to keep veering off to the eastward, using the thermometers to give us a good offing from the weather edge of the ice.

When visibility improved the first land we saw was Cape Queen, high over the water. And at about this time we rounded the point of the ice and ran south, paralleling the coast six or seven miles off. We worked along past the Trinity Isles in as beautiful a night as I have ever seen. A few clouds were mixed up with the thousands of stars, and once in awhile the northern lights would flood the sky. The moon was almost full, too, and it was very light. The east wind, blowing off the Dorset Land shore, was as balmy as though it were coming over the Sound from Long Island.

The next day the wind was strong, and I had to give up my plan of going between Salisbury and Mill Islands. We tacked instead, and anchored in an unnamed cove on the Dorset shore, calling it McKelvey Bight in honour of Junius Bird’s Peggy McKelvey. The crew had a good chance to stretch their legs here, and after that we came down to Turnavik without adventure. I found the people there very well, left some supplies, and made a nice run to the Indian Tickle. We were caught there by a northeast gale, and rode it out under Rover’s Island.

From this point to the Domino is about 24 miles, and it is a part of the coast with which I am not familiar. The small scale chart I had was not so good, either, but two of my men had fished there for 11 years, and I figured that they ought to know the water. This proved to be wrong. At the entrance to Domino Run coming from the north is a small island, and ships must pass to the eastward of it. We were pretty close inshore, and I was up forward with one of my sailor pilots when the Morrissey struck. She hit again as I was turning, and I rushed aft, yelling to the helmsman to port his helm. He did without trying to stop the engine, and thanks to this we were clear in a few seconds. Fortunately we had been just on the edge of the shoal, and our luck was driven home when the ledge broke clean out of the water in the swell just after we got away. If a comber had dumped us onto those rocks, I would have been collecting my insurance on the schooner a little while later – if I outlived her.

The great difficulty now was to work off the lee shore. I had not a rag on her, and the engine wasn’t powerful enough to buck the wind, tide, and current in the run. I sang out to give her the linen, and believe me, sir, there was no lack of willing hands to help with the canvas. In a brace of shakes we had the foresail, jumbo, and trysail on her and these, with the engine, took us offshore into deep water, and through the run. Once safely in the Atlantic Ocean we had a rough ride, but a fast one, and the only trouble was that the pounding on the ledge had given that leak in the propeller sleeve a whole lot of encouragement. Otherwise she didn’t leak a drop.

From here to Brigus we had a splendid run, and tied up at our pier just as we had many times before. Norcross, Robert Dove, and Jack Angel left us, and I spent a few days with mother before taking the Morrissey to the McWilliams yard, where we laid her up for the winter. Another cruise was done, and with it a lot of excitement and a lot of wonderful times – mixed with some bad ones.