NORTH GREENLAND, 1926

Some time after returning to New York I met George Putnam, the publisher, and was subsequently invited to visit him at his home at Rye, New York. I accepted and enjoyed my weekend very much. We were strolling in the woods one day, and I was telling him about the Morrissey and her fishing trips. He appeared to be interested, but still I was not prepared for what followed. He turned to me and said he wanted to make a trip to the northwest coast of Greenland. He wanted to take Maurice Kellerman along to make moving pictures.

Well, I told him what I knew of the north, and of my experiences there, including those with Peary, and I outlined my ideas of what a boat would have to have if she were to have any success up there. These ideas included power and at least two powerboats. And the long and short of it was that George decided he would make the trip in the Morrissey. The question then was how soon could she be prepared. She was at Brigus, of course, and would have to be brought to New York in the spring. We couldn’t get her there before that time, as I had agreed to go seal hunting with Father. He said that was all right, so off I went.

Things broke badly for me, as we had a hard spring. Father’s steamer had a lot of engine trouble, and in addition encountered very bad ice that delayed us. In April I received a radio message from George that everything was all right. He was wrong. Everything may have been all right at his end of the line, but I was a long way from Brigus, and as a matter of fact I did not get there until May 3, at which time I should have been in New York for the installation of the engine.

Immediately I was in Brigus I had carpenters get to work, and they did a quick job of fitting cabins, and sheathing the hull with greenheart, a very hard wood that comes from Central America, and is much used by vessels that work in the ice for additional protection. When this work was done the Morrissey was put into the water, and on May 10 I signed on a crew at the customhouse, leaving port the following day.

The wind was light, and we towed out to open water, setting all four lowers and sliding off to a slow beat to windward. We ran into fog, no novelty for these waters, but we also found a heavy swell, and the bowsprit began to work in the knightheads. This forced us to lower the mainsail and the headsails and lie to under the foresail while we uncovered the gear forward. After working for several hours we drove wedges into the collar of the bowsprit iron and made fast the heel, after which we jammed on sail again and resumed progress toward our destination.

We didn’t raise Cape Race until Friday, May 14, and at 7:30 a.m. we had it abeam. It had taken us four days to cover 60 miles, which is what will happen sometimes when you have no engine and are at the mercy of the winds. But then the breeze came in strongly, and we logged along in great shape until it blew so hard we had to reduce canvas. This was too good to last and it went into the west, lightening almost to nothing. More fog came down on us, and we slatted around for hours. We just barely had steerage way, but there was nothing to do about it but hope and whistle for a breeze.

When it struck in it was a very light southwesterly, a headwind for us, and as the swells continued, we kept on slatting around. Our sails and gear were showing the effects of this mauling, for the way the main and foresail booms and gaffs swung around that sea was bad news. As a matter of fact we had to douse the mainsail once for a couple of hours so that we could mend the tears in it. It was maddening to want so badly to be making up time already lost and instead to lose more. We didn’t get to Nantucket lightship until May 25, when a southeasterly gale arrived and sent us along in fine fashion.

This was a fair wind and we made the best of it. By and by we passed a big four-masted schooner lying at anchor. It didn’t really take the presence of two Coast Guard patrol boats to tell us that she was a rum boat waiting for runners to put out from the shore to get loaded. She was outside the territorial limit, and the Coast Guard craft couldn’t touch her. They could, however, pick off the rum-runners after they were loaded, if they could catch them, and that was what they were waiting for. I hailed the skipper of one of the patrol boats and asked him to radio a message to George, for I knew he was having 59 different kinds of fits over our delayed arrival. But the Coast Guard skipper looked us over, saw we were from Newfoundland, and probably thought we were carrying rum ourselves, for he told us we could deliver our own message, that he couldn’t be bothered. And that was that. The newspapers of that day were full of stories about yachts getting shot up by the Coast Guard, and I suppose we should have been glad he didn’t blow us out of the water, even though I knew that if he’d searched us, he wouldn’t have found enough liquor aboard to disturb canary bird – or the Anti-Saloon League, either. Right then my opinion of the Coast Guard was as low as our garboards, but I later found out that I was wrong, that they are a great crowd, helpful, efficient, and willing.

However, this one didn’t feel like helping us, and we kept plugging along, making the Ambrose Lightship the same night. We anchored for daylight and a pilot, and when we had both we got underway, just making quarantine before the wind dropped and the tide turned. It’s nice to have a fair wind there, and a fair tide is a necessity if you have no power. Once arrived, I went through the immigration and customhouse forms, and rushed ashore to telephone George and the McWilliams shipyard at West New Brighton, Staten Island. A tug was soon alongside, and we reached the yard without incident.

As we tied up, I saw George and a friend walking along the dock. I greeted him, informally, and George at once broke into a roar of laughter. I asked him what the joke was, and he explained that he had made a bet with his friend as to what my first words would be when I was within hailing distance. George won, too, called the exact words I used. I’d like to repeat them here, to show how well George knew how I reacted to things like slow passages at sea, but they sounded a lot better than they would look on paper.

It developed that our lateness in making port had alarmed George, and that we had been reported as missing in the press. On our way to Rye for the weekend he showed me my obituary printed in some newspaper, it being the first time I had ever seen that sort of a write-up about myself. I also received letters from several of my friends telling me they were glad to learn that I was still alive. Why, hell’s bells, we didn’t make a half-bad passage, considering the conditions. You can’t run a sailing vessel on a schedule the way you can an ocean liner. And we got there all right.

But there was no time to think about what was past with so many things to be done to the Morrissey. After a delightful Sunday at Rye I came to New York – it was Decoration Day – and we began working on the ballast, getting 35 tons out by nightfall. I got together with Tommy Miles, foreman of the yard, on what was to be done to the Morrissey, including the installation of the small diesel engine, which was already in the McWilliams’ shop, and numerous changes around the deck, not to mention putting the fuel tanks into her.

The Morrissey went onto drydock on June 1, and we worked in a terrific rush, something that I have been paying for ever since. You can’t hurry these things if you want a really good job, and the result of our haste was that things were not as shipshape or as well-organized as they might have been. The platform bed for the engine, the installation of which is a job requiring great care and time, was very well-done considering how hurriedly it was made, but from any other point of view it left something to be desired. The fuel tanks should have been made to fit the contour of the hull, instead of being square and taking up far too much room. And the propeller shaft should have been lined up correctly, as would have been the case with a proper engine bed. But it was a rush job, and day and night work continued until June 4, when we went overboard again and began to paint, overhaul the rigging, fix the crew’s quarters, and do all the other things that crop up in fitting a vessel for sea.

On June 16, we began putting aboard stores. Apart from our own stuff, we were to bring supplies for Doctor Knud Rasmussen to his station at Thule, Northwest Greenland, and it was quite a job getting all that truck aboard. At first it looked impossible, but we did it. I stayed on the job myself, seeing to it that every hole and corner was filled up. Some of the stores were in big boxes, which had to be opened and their contents removed. In a vessel like ours big boxes are a damned nuisance and should never be used, particularly in the north, where you are likely to have to get at things in a hurry. If you are caught in the ice and are being crushed, there is mighty little time to get away, and supplies should be in small, handy boxes. But we got everything stowed, with some space left. This was necessary, for we were to take with us Professor Hobbs and the University of Michigan Expedition, and they would need room for their gear.

With this job done, we tried out our diesel engine at the dock, and were gratified when it ran smoothly. Robert Peary, son of the admiral, was my chief engineer, and he was right on the job, with a thorough knowledge of mechanics that later proved very useful. And at noon we were off. I wasn’t taking any chances on our engine going dead in the lower bay, and had a tug standing by, but it wasn’t needed. We threaded our way among the ferryboats, car floats, tugs, liners, and all the traffic that makes a watery 5th Avenue and 42nd Street out of that locality, and headed up the East River. We had timed the tide perfectly, and slipped through Hell Gate at slack water, with the ebb under us after that to help us along to City Island from there to Rye.

We anchored off the American Yacht Club that night, looking very trim and smart, with sleek black hull, black rigging, and scraped and varnished yellow spars contrasting with the white paint of our upper works. On deck she wasn’t so attractive, I’ll allow, for there wasn’t much room to walk about. Gasoline and diesel oil barrels lashed here and there, with our two whaleboats forward, saw to that. Below deck it was the same story. But just the same, the Morrissey was the centre of interest among the impressive fleet of yachts anchored off the club, and we were visited by scores of yachtsmen and yachtswomen before we departed at 4:00 p.m. the following day.

When we steamed out of the harbour we had an escort of two power yachts, and they stayed with us as far as Stamford. From then on we were on our own, running before a brisk breeze. We made good time and by the next night had left Pollock Rip astern and were squared away for Cape Sable and the coast of Nova Scotia. There is a great kick in being at sea again after a time on shore, to feel the wheel in your hands again, and the lunge of the vessel as she smashes along with a bone in her teeth, to know that every halyard, sheet, and stay is good and true. By God, sir, there’s nothing like it, and that’s something you can tie to.

On the 26th of June we dropped anchor in the roads off North Sydney, Cape Breton, and filled our water and fuel-oil tanks. This was the last place on the way where we could get oil and gasoline at reasonable prices. Up north, in the great majority of cases, the people and the government stations keep fuel for emergency use, and they don’t like to part with it. I respect this feeling, and I took aboard sufficient oil to bring the Morrissey back again.

We also picked up the University of Michigan Expedition here. I well remember the impression Professor Hobbs made when he came over the side. He was tall, lean, and wiry, with long flowing whiskers, and he had prodigious energy. That was the amazing thing about him. He boiled with it. Every move he made showed that tremendous supply of strength. Dennis, who runs the boarding boat for Fen Kelly, ship chandler of North Sydney, was particularly impressed, for he had met the party at the railroad station, and he had see the professor in action.

“What a man!” he exclaimed to me afterward. “What a man! He looks old, doesn’t he? But he’s got a hell of a lot of pep, skipper, and believe me, I’d hate to be following that old man with a 70-pound pack on my back up in Greenland, where the mosquitoes are so thick they slow you down when you walk. No, sir, skipper, you can have it if you want it. He’d walk you bow-legged, until you’d have to trice yourself up to a snatch block if you wanted to keep on your feet.”

With the Hobbs party aboard, and the last of our supplies loaded, we got underway again, looking like a sailor’s nightmare, with bundles of hay, canoes, tin boats, collapsible boats, rubber boats, and God alone knows what else the entire length and breath of her. In addition to a big cargo, we had a full passenger list, and then some. Every bunk below was filled, and seven or eight cots were rigged up in the saloon. I think we had about 34 souls aboard, 10 more than we were fitted to carry.

Among them was an honest to goodness cowboy from the sweetgrass region of Montana, Carl Dunrud. He’d never been aboard a vessel before he stepped on the Morrissey’s deck, and he’d never smelled salt water before arriving in New York for this trip. But I size a man up pretty quickly. When I’ve talked to him a little while I know what’s in him, and it didn’t take me long to realize that there was no mistake in bringing him aboard as one of us. George Putnam’s son, David Binney Putnam, was aboard, but he was no stranger to the sea, having visited the Galapagos with Doctor William Beebe.

Dan Streeter, I suppose, deserves a paragraph to himself, for he later wrote an entire book about the cruise, in which he panned us and the trip to a fare-thee-well. Dan was a man of importance on the Morrissey, for he slept on top of a crate of oranges, and had sole charge of what happened to them. Sometimes the air in the schooner got pretty high, due to the reek of the diesel oil, but the smell of the oranges put up a good battle, and made our mouths water. Well, he wasn’t a bit stingy about it. He’d let us look at the oranges anytime, and every once in awhile he would relent and let us have a taste. But I want to say you couldn’t have a better shipmate than Dan. No matter what you asked him to do, or when you asked him, he did it cheerfully. From the day he went aboard until the day he left, there was never a frown on his face, which is a lot more than could be said for mine, considering all the things we went through before we tied the Morrissey up in New York harbour again.

Others in our complement were Art Young, the bow and arrow man, who had killed lions in Africa, and grizzly bear, moose, and kadiak bears in America with his chosen weapons; Maurice Kellerman, official cameraman, and Ed Manley, an amateur radio operator. All in all, it was a fine crowd, which was just as well, for we were to be in pretty intimate touch with each other for some time. If the gang on a schooner the size of the Morrissey isn’t congenial for the greater part of the cruise, and by greater part I mean that following the time when the men are strangers and on their good behaviour, it means a lot of unpleasantness. We were lucky.

Soon after we got away we began something that has been done at frequent intervals since on my trips into northern waters. We dropped overboard a sealed bottle for the Hydrographic Office of the Navy Department. In the bottle was a slip of paper bearing the name of the schooner, the captain, the latitude, longitude, and the date. It was hermetically sealed, and allowed to drift wherever the currents took it. If the finder was sufficiently interested to take the trouble of forwarding it to the Hydrographic Office in Washington, with data as to where it was picked up, a good idea of its drift could be determined. This was valuable information in the study of ocean currents and in the making of charts.

Why, my dear man, some of those bottles were found, years afterward, on the English, European, and African coasts. Imagine that! The first bottle went overboard when we were 25 miles northwest of Cape Gregory on the Newfoundland coast, and we followed it with others whenever we couldn’t think of anything else to do, and some of them travelled all those thousands of miles before being found. I know that the more expert yachtsmen on Long Island Sound go out with sealed bottles and drop them over near some buoy that they habitually use as a turning mark, in order to find how the tide and currents run at various times, and this work of ours was really the same thing on a large scale.

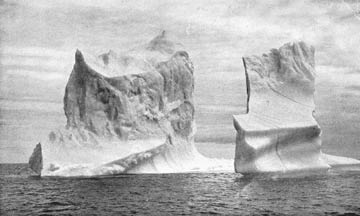

In the midst of our bottle heaving we entered the Strait of Belle Isle, where they invented fog, and here many of our crowd saw icebergs and growlers for the first time. To those of us for whom ice was no treat, it seemed strange to hear these people go into raptures over the beauty of it all. I guess the more you see of ice the less you think about its beauty, and the more you wonder about what it is meditating to make things unpleasant for you. I noticed that the novelty of the sight soon wore off, and our neophytes – they were not, with very few exceptions, landlubbers – quickly became as blasé as any of us. As we got through the strait and ran along the coast of Labrador the bergs grew larger and more frequent, as did the growlers. During the afternoon of June 30 we ran into field ice.

I had in mind to go to the southward around it, but it didn’t appear to be very thick, so we doused sail, and proceeded on our course under power. In that latitude darkness only lasted an hour or two, and when it shut down we lay to until daylight, and then proceeded. The floes were fairly closely packed, and at times very heavy, but we had no trouble, pushing our way through in great shape. And finally we noticed that the swell was hitting us, which was a sign of clear water ahead, for heavy field ice flattens out a swell in short order. We got more indications as we went along in the form of gulls, phalropes, and other birds that fly near the outside edge. As night began to close in, we ran into clear water, after working through 90 miles of ice.

The lookout picked up land on the evening of July 5, making the Sukkertoopen, Greenland, on the starboard bow. We worked far closer inshore than I had ever sailed before, and this was new territory to me, for Admiral Peary, when he was working in the north, never stopped at any of the harbours of South Greenland. At least, that is my recollection. After leaving Labrador, his first stop would be Cape York, across Melville Bay, paying no attention to intermediate points. We couldn’t do this, even if we wanted to, for we had to stop at Holstenborg to land the Hobbs party.

I knew we were somewhere near there, and we kept a sharp lookout for a pilot. We found one, cruising in a kayak, and he was delighted to come on board, indicating that he wanted to take the wheel. My Eskimo lingo wasn’t as fluent as it used to be, but we managed to understand each other, and he took us in as though handling a schooner was his life work. Once at anchor, we saw the governor and his assistant come out in their clinker-built whaleboat, with the Danish flag flying in the stern sheets. They boarded us, inspected our papers, found them to be all right, and gave us the freedom of the place. We took advantage of this to fill up with fresh water and to overhaul our engine.

I suspected that being aboard the Morrissey would be a novelty for the governor and his assistant, because life is pretty much of a monotonous affair in Greenland, and I invited them to accompany us up the Ikertok Fjord to drop the Michigan party. Dan Streeter says that this group of scientists believed that bad weather originated in Greenland and were intent on finding the breeding place. It might be so. I don’t know. But we put the scientists ashore and returned to Holstenborg, stopping there long enough to drop our guests.

Then we were off to Disko, encountering strong headwinds that forced us to anchor inside King-Ek Island. Here was a chance for our own geologists and archaeologists to get ashore, stretch their legs, and do some research work. The less technically minded members of our gang also went ashore, and inspected the bird rookeries and the Eskimo settlements around the island. Before the spectacle palled on them, the wind shifted, and we ran on to Disko.

I had last been there when I came in with the Neptune to pick up some of the members of the Crockerland Expedition. I had been up as far as Etah, where I found MacMillan and brought him south, and we had had plenty of trouble. It was a year of the worst ice conditions I can remember, and the run from Sanderson’s Hope was a constant struggle. The return voyage was just as bad, with continual pounding through heavy ice. By the time we reached Disko we were making so much water that the pumps could just about take care of it. The only way we kept going was by driving wooden plugs into vacated bolt holes, and by wrapping canvas around the stem below the waterline. The governor of that day had wondered when we left in the Neptune whether we would make our destination or not, and he was still here, so when I arrived in the Morrissey I told him that we had made it all right. He, with Doctor Porsild, one of the experts on Greenland, entertained us on shore, and we enjoyed ourselves thoroughly.

We didn’t get much of it, though, for we had much sailing to do, and after refilling our water tanks, and transferring diesel oil from barrels on deck to the tanks below, we were on our way. I had thought of going through the Waigat, a thing I had always wanted to do, and had never got to. But I was blocked again, as the wind was strong and blowing right out of the fjord. Aside from that it was a worthwhile day, particularly from the point of view of scenic beauty. Crossing the mouths of the fjords on the west side of Disko Island, the land, with its cascades of running fresh water, and its birds in the loomeries, and the sea, with its bergs and floes and sun-flecked spots furnished a background that fitted well with the weather we drew.

It was so warm in the bright sunlight that we sat on deck in light clothes, and this despite the presence of great, towering icebergs in all directions. What impressive sights those tremendous chunks of ice were! They were shaped in every conceivable formation. If you looked long enough and carefully enough you could find the counterpart in shining ice of the Woolworth Building, the Chrysler Building, the Empire State, Radio City, a castle, an abbey, or anything at all. And every bit of it was washed with that wonderful warm sunlight. It was beautiful while it lasted, but after we had left Disko Island astern the fog rolled in.

That made all the difference in the temperature, for warmth in the north does not linger, vanishing almost with the disappearance of the sun from which it comes. The thermometer dropped to below freezing, and the condensed fog began forming icicles in the rigging. Even under the most favourable conditions navigation is very difficult in these waters, and in the heavy fog it was exceedingly tricky. It almost cleared up at one time, and we managed to get into a small place named Proven, sending the whaleboats ashore to do some bartering. It shut down again, and kept us there longer than I had intended staying, and the minute visibility improved, we put out again and laid off our course for Upernivik. But we got fooled. It was another false alarm, and the fog came down again, thick as mud.

Conditions were very unfavourable, and there was no visibility at all. You could have had the Leviathan 50 feet away from you and never have seen her. Coupled with this in making life difficult were many unchartered shoals, some of them so steep that the lead was of no use whatever in trying to find them. The first thing you knew about the existence of one of these was when you smacked into it. Sometimes it is possible to find where danger lies by noting stranded bergs and growlers, and I proceeded by this method of navigating until I thought the Morrissey had run off the distance to Upernivik. Then I turned squarely inshore.

Our landfall was pretty good, but while I could tell that we were near our destination, it was difficult to distinguish one island from another in the fog. I didn’t want to lose the advantage we had, and yet I dared go no farther ahead, and so I made use of a plan that has many times helped a skipper out in the north. I saw two bergs stranded about a quarter of a mile apart. They were close enough together so that we could see them almost all the time, and I maintained our position by cruising back and forth between them until the wind hauled around to the eastward, and we could see the headlands around Upernivik as the fog thinned out. I put the Morrissey on the course, and by good luck and a sharp lookout we managed to get in without hitting any of the dangerous pinnacle rocks that bar the way. At the harbour entrance we picked up an Eskimo in a kayak, and he took us right in. By the time the anchor was on the bottom old Otto, the governor, was alongside, bidding us welcome. He came of a noble Danish family, and every time I looked at him I was reminded of Otis Skinner, the actor. Otto had lived in Greenland for many years, and he was delighted to see us. Strangers are always a treat up in the north, and he offered us every hospitality. Those of us who were not engaged in research work availed ourselves of it, especially Dan.

Dan found a kindred spirit in Otto, and the times they had were a classic of high life in the Arctic. I had some nice talks with the old governor myself, and he told me that the harp, or Greenland hair seals, were becoming scarcer, a point on which he was in agreement with Doctor Porsild. Both men, who should know, qualified their opinion to the extent of admitting that the Eskimos might not be as skilful in hunting as in the earlier days, when they had been forced to depend upon the seal for their very lives, and they added that the animal might be getting smarter and more wary. I had an argument here, too, with the Eskimos, who told me they had never seen codfish north of Uminak. I had an idea that both cod and halibut could be found if sought, although not in great quantity, as far north as Whale Sound, Northwest Greenland.

All this was very interesting for me, for the natural resources of the north are among my hobbies, but we could not stay here indefinitely, watching Dan and Otto sample wines. We hove up anchor on the afternoon of July 17, having clear weather long enough to take us to open water. Then our friend the fog came in as thick as pea soup, but as we were clear of the land and the icebergs, we pushed on to the Duck Islands, and from there to Cape York, where we built the Peary Memorial in 1932, crossing Melville Bay in 29 hours, which was a good run. We spent a wonderful afternoon at Parker Snow Bay, where are the beautiful bird loomeries, but our destination was Thule, and we went on to that place, where we anchored.

Hantz Jensen, Rasmussen’s agent, came aboard, and was greatly disappointed to find that Rasmussen was not with us. I explained that we had planned to pick him up at Disko, missed him there, and tried again at Upernivik, with no better luck. It developed that his time of departure from Copenhagen had been delayed. We did meet up with him later on our trip, and when we did we were very glad to see him, for we were in trouble and needed the help that the crew of the craft on which he was a passenger could give us. As I say, Jensen was disappointed, but his grief was assuaged when he found we had a box of apples aboard. A year had elapsed since he had tasted an apple, and he must have polished off half a dozen before he had had enough.

When Jensen left us, we sailed along to Sander’s Island, and devoted ourselves to getting into trouble, with complete success. We had stores for Rasmussen’s station, but did not take the time to unload them, as we were anxious to get to Sander’s as quickly as possible. I had been there twice before, once when I was mate on the Windward in 1898, and again in 1910 on the Beothic, with Paul Rainey and Harry Whitney. On both these occasions we visited the loomeries and got some eggs and saw a lot of ducks, but managed to keep out of trouble. This time there was a scarcity of ducks and eggs, but – well, we were damned lucky to get away with our schooner, and that’s no lie.

Dan Streeter was responsible for our first jam, with all the innocence in the world at his side. He had brought along a high-powered rifle, and on this particular day he broke it out and lugged it up on deck. Few of us were aboard, but among them was Robert Peary, which proved to be a good thing, for Robert knew the north and he acted promptly, anticipating my orders. He stood beside me as Dan opened fire on a pinnacle of ice on one of the bergs. I watched him fire a few shots and then told Robert he had better stand by his engine. He dropped below, and Dan kept on firing.

The berg was just a few yards away from us, and I didn’t much care for the possibilities. They became probabilities when I saw pieces of ice begin to come sliding down the side of the berg. In two seconds I was at the wheel, yelling below to Robert to get the engine started. He had had the same hunch as I had, and the motor was already going. The berg by this time had begun to sally, and several of my men slipped the anchor chain. I liked that anchor, and wanted to keep it, but I preferred to have the schooner, and it looked like a choice of one or the other. As I slipped in the engine clutch the berg was rolling heavily. Have you ever seen an iceberg roll? Well sir, it is an impressive and fearsome sight. I knew what was coming, coming just as sure as fate, and when the engine missed once, I think my heart missed a beat too. It wasn’t just a case of injuring, or even losing the Morrissey this time. It was a matter of all our lives, and it was a matter of split seconds.

The diesel continued to run, and we picked up way, with the berg’s sides rolling over our heads. It was no fun, looking up at those smooth ice walls and thinking what would happen if they came down on us. And we had barely covered a boat’s length when the berg capsized, smashing into the water we had just been floating on with a crash that left no doubt as to what would have been our fate had not Robert had the engine running. As it was, it was so close that I thought it would get the end of the main boom. That was plenty near enough for me.

The thing about these bergs is that their centre of gravity – their metacentric height, if you want to call it that – is constantly changing, as the water melts the under part of the ice. This means that the stability of a berg grows constantly less, and the result is an ever-increasing tendency to roll. When it gets on the borderline, or close to it, not much is needed to disturb its balance, and once it starts to roll the chances are all in favour of its capsizing. The sound waves set up by a gun or a whistle can do it to a delicately balanced berg, and shooting at one with a rifle is just asking for trouble. Dan found that out, but thanks to our engine we had escaped.

You would think this would have satisfied us, but it didn’t. A little while later we were in another mess, a worse one. I don’t believe I’ll ever come closer to losing the Morrissey without actually seeing her go than I did that time. But we’ll come to that presently, in its proper place.

Out of our troubles with the ice we decided to go back to Thule and land Rasmussen’s supplies. He had enough stuff to make four boatloads, and it cost us considerable time and effort. When it was done we celebrated by taking off for Inglefield Gulf with a fair breeze and all sails set. The wind was perfect, not too strong, and not too light, and the sun burned down in glorious fashion, making every wavetop sparkle like jewellery, and turning the water from sullen grey to a delightful dancing blue. The Arctic can be beautiful when it is in the mood, no doubt about that. It can be warm, and pleasant, and attractive. But this isn’t often the case, and I don’t suppose anyone goes into the north to have a pleasant time. It is an adventure pure and simple, a struggle against cold, ice, inability to get fuel or supplies. And that is what you find most of the time.

But here was an exception, just the kind of day a sailorman loves. We took advantage of it to visit the Eskimo village at Netchelumi, and tried to get in to Itiblu, but the ice kept us out. We sailed across the north end of Herbert Island, only to be blocked again by unbroken sheets of ice. Consequently we worked in between the ice and the mainland. It opened up the next day, and we went on into Murchison Sound to Karanak, named because the cliffs there look very much like those at Karanak, Egypt. We could get within three miles of the cliffs, but no nearer, as bergs were holding the field ice in and it cut us off. But there was clear water between Northumberland and Herbert Islands, and we went there, keeping our rendezvous with trouble.

I had in mind to go to the little Eskimo village of Keeta, a place I had visited many years before. The land around here all looks alike, and I was afraid of missing the place if I were too far offshore, so we kept pretty close in, with a keen eye for igloos, until we came to a place where a large raised rock known to geologists as a dyke ran out for about half a mile into the water. I took a look at it, and told the helmsman “Hard a-starboard,” for I recognized the dyke and knew the village was in the next cove. I felt pretty smart about remembering the place, and was just turning to answer Harry Raven, who had come out of the forecastle to tell me they were having a mug-up, when the Morrissey, cutting too close, smacked the ledge.

She hit it at full speed ahead, and at dead high water. I didn’t like the feel of things a little bit, for I didn’t know but what we might be there a long time. Maybe forever. At least, the Morrissey might. We could leave whenever we pleased. But I had small taste for leaving my beloved schooner on a bed as cold and forlorn as the one she had picked. And incidentally, I’d rather sail home in her than in a whaleboat. This being the case, it was up to us to get her off, or try to, so we hopped to it without delay.