FOXE CHANNEL SECTION, 1927

The mistake of starting too late the work of getting the Morrissey into shape for sea was not made this year. By the 1st of March I got my brother Will, Billy Pritchard, and Jim Dooling down from Newfoundland and we moved the schooner over to the yard of Tietjen & Lang, in Hoboken. For the damage done to the Morrissey’s hull while she roosted on the reef the year before the insurance company had given me $1,500, and I used this money in fitting out. It is amazing how many things have to be done to put a vessel into commission, and how they can run into time and money. New planks were needed for the wake of the forward part of the raised deck, where she had been strained quite a bit. There were a number of rotten spots in her deck, although not a drop of water had got through to impair any of the deck beams, knees, or stanchions in line with the waterway or underneath the deck.

One thing I felt we had to have was a new mechanical windlass to take the place of our old-fashioned barrel one, which was not at all suitable for our work in ice and in harbours where ice abounded, with the constant threat of having to move out in a hurry. We got it, and I bought and paid for it by writing an article called “My Troubles With Women.” I reckon everybody has had troubles with women, or else they don’t know any females, and so the title proved good enough to sell the piece. That meant our new windlass and the end of that infernal barrel contraption that was such a thundering nuisance to work, and that caused Dan Streeter so much pain. Pumping on that windlass and eating Billy’s boiled potatoes were the only things about the Morrissey Dan didn’t like. The new one, I might add, saved our lives in the course of the trip, and paid for itself right there.

I also acquired an extra whaleboat with a Palmer engine, and I installed a 10-horsepower Husky to hoist the sails. It’s all very well to talk about the days of iron men and wooden ships – so long as you just talk about it. It sounds romantic and all that, but let me tell you that life at sea is happier in the present day when you have machinery to do the work that men used to have to do themselves. And what’s wrong with it? I shipped aboard sailing vessels in the old days, and may I be keel-hauled if I’d trade back. It seems to me that anything old-fashioned gets surrounded by a wall of hokum.

And anybody that thinks that real sailormen died out with the age of sail is all wrong. There are still plenty of good men on the sea, and a lot of them wouldn’t know what a main t’gallants’l was if you gave them a lecture on the full-rigged ships. But they know their own game, and things happen all the time to prove it. How about these rescues at sea? It takes a real man and a real sailor to launch a lifeboat from an ocean liner. Take it from me, it’s a tougher job than it ever was to get a boat away from a sailing ship. Those high topsides in a seaway are a constant menace to a boat. And yet men like Harry Manning, who was raised in steam, will get a boat away in a whole gale, row it to a distressed vessel, work in close enough to rescue the crew, and bring them back again. As long as they can still do that, there’s no need to worry about sailormen softening up, and you may lay to that, for there’s no tougher job on the sea.

Well, we seem to be making a lot of tacks getting out of the harbour on this cruise, but we’ll fetch up where we want to go before we get through. So ready about, and let’s get back on our course. Along with the new windlass we put in new anchors and chain. Some planking on the outside of the hull was renewed. I also installed a new rudder, and a special ice propeller, a small, tough wheel something like a towboat’s. Then I felt that we were pretty well-prepared for the north, although I wasn’t yet, and never have been, satisfied with the installation of the diesel engine. It wasn’t the yard’s fault. It was just that we were hurried, and the propeller’s shaft had given us trouble to this day.

On board the Morrissey on this cruise we had David Binney Putnam, Larry Gould, assistant director in charge of geographical work at the University of Michigan; Don Cadzow, anthropologist of the Museum of the American Indian; Robert Peary, chief engineer; Doctor Peter Heinbecker, surgeon; Ed Manley, radio operator; the late Frederick Limekiller, taxidermist; John Pope, of Detroit; Monroe Barnard, son of George Gray Barnard, the sculptor; Junius Bird, of Rye. Junius was on his first trip with me. He hasn’t missed one since, and I hope he never will, for he is the sort of man who can do anything, a useful type to have aboard. Mrs. Putnam accompanied us as far as Brigus.

I might say that having Mrs. Putnam with us was a concession on my part. I don’t hold with most superstitions, but I do think it’s bad luck to have a woman aboard a sailing vessel, whether the craft is underway or not. I admit that I’ve got myself into trouble plenty of times when there wasn’t this excuse. Nonetheless, I believe in it, and lots of sailormen would tell you that any hard luck that came to us in the course of the trip was our own fault, that we had asked for it by having a woman aboard. On the other hand, they always have a woman christen a vessel, and that is supposed to bring good luck. So it’s hard to tell just where you are in this superstition matter. You think, by God, that you’re filled away, and the next thing you know you’re all aluff.

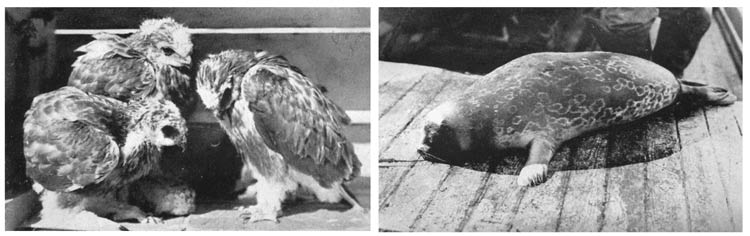

Anyway, we had Mrs. Putnam aboard from the American Yacht Club to Brigus, where we arrived on June 20, and when she took her dunnage ashore we missed her. She fitted in perfectly with the ship’s life aboard, and the best thing about her was that she minded her own business. She was no gossip – and a real gossip can make more trouble at sea than any 10 jinxes you can think of – and whatever she saw and heard remained her own property. Not that much got by her. It didn’t. She was like the wise old owl in the tree, who became more and more silent as he heard more and more that would make good telling. And for the logbook, let me add that we had the best of luck while she was aboard.

When we tied up at Brigus I couldn’t help contrasting the Morrissey then as she was when she was last there. At that time she was just an old fishing schooner, a well-found, sturdy vessel, with none of the conveniences of life afloat, as you might say. And now – why, my dear man, she was an auxiliary schooner with some pretensions to respectability. She had new sails, a new deck, a modern automatic windlass, electric lighting, a new galley stove, and many other things that don’t come to mind that weren’t there in the earlier days. I don’t know how old Skipper Morrissey would have liked her, but I know she was far better equipped for going into the north than she ever had been before.

We were in port for three days, and I had a fine time showing off the Morrissey to the homefolks. Among them was my mother, and I can never tell how wonderful it was to have her on board, looking over my schooner. She is now more than 80 years old, and is intensely interested in everything that is happening. I really believe she is more keen about what is going on in the world than she was half a century ago. But pleasant as this was, we couldn’t stay here very long, and soon we were on our way up the Labrador coast, encountering the ice on the southern part. But we were fortunate in having southwest winds that enabled us to sail up inside the sheet, and at length we reached the Moravian mission at Makkovik.

It was here that I was saddened by learning of the death of Tom Evans, our caretaker at Turnavik, and of Harriet, his wife. They were ever faithful to my father, and had served him well for more than 50 years. They had seen Turnavik grow from a wild place where there was not a house or a sign of any habitation to one of the greatest and most prosperous fishing stations that in the latter part of the last century dotted the length of the Labrador from Cape Charles to Cape Harrigan. They had also seen its decline, becoming again a place infrequently visited. I had a small heart for stopping at our station now that I knew Tom and Harriet were gone, but I did put in to say a prayer for them and to see that things were all right. Then we were off again.

We cruised from Turnavik to Sculpin Island. I had heard that there were traces of Norse settlers here, men who had come over from Iceland and Greenland in the days before Columbus was born. We wanted to have a look for any data we could find bearing on this subject, and dropped our hook there. I can’t help thinking that if the Norsemen actually did settle there, they were not very bright, for they could have chosen many nicer places to hang out their shingle. We found no proof at all that they had ever landed on the island, which was bare and bleak. But the legend of their presence there seems to be pretty strong, and I wonder what happened to them? It isn’t difficult to construct a likely theory.

What must have happened shows how hard life can be for settlers who settle in the north. The Norsemen made their homes on the island, probably built stone houses, but they were no more independent than a colony there would be today. They had to count upon vessels from Iceland and Greenland for supplies. The soil was not suitable for agriculture. They could raise little or nothing. There was not sufficient game on the island to give them meat. They could fish, and they undoubtedly did, but this did not alter the fact that without help during the summer they could not have enough supplies to tide them over the frozen-up period.

And in all probability they encountered a hard year when the ice never did go out. It may have lasted several years, and in that time no communication could be had with the source of supplies. The result was gradual starvation, the whole thing ending with a finish fight with the Eskimos. If any weren’t killed, they were assimilated by the latter group, but the fighting reputation of the Norsemen was such that I doubt if any surrendered. It was a battle to the death. And today all that remains on the island are some abandoned Eskimo houses. We were disappointed at not finding any evidence at all pointing to Norse occupation.

Our profitless exploration concluded, I took the Morrissey out of the ice, and we celebrated the Fourth of July off Cape Chidley, at the extreme northern end of the Labrador. I was taking a chance in going out there, for it is a poor place to be caught by the ice. There were plenty of fine shelters in the bays and fjords along the coast where we could have passed the time pleasantly, and to some advantage, but I gambled that we wouldn’t be trapped by ice running on the terrific tides they have up this way. We lost, and the Morrissey was caught for fair between two sheets. It was a bad situation, with those great masses of floe ice grinding against the hull. Our propeller and shaft carried away almost at the start of it, and we were nipped too tight to get any benefit from our sails. We were helpless and at the mercy of the drift ice, tide, and wind, driving over unchartered shoals and between countless small islands.

All hands were called to quarters, ready to do all they could to get the Morrissey out of her difficulties if possible, and to abandon her if this could not be done. Our objective was to work in toward shore as much as possible whenever the ice opened up enough to let us move. When this happened we used our motorboats to tow us through the leads, and occasionally we were able to make sail. This was very dangerous, though, because of the chance that the schooner would pick up too much way on a puff, and tear her bottom out on a sharp spur of ice. At times we had all hands out on the ice, trekking her along with lines. And there was the constant fear that the floes might close in and crush the Morrissey the way a man folds up an accordion.

For days we could see no end to the ice. It took patience and continual hard work to make any progress toward open water, and while we were doing it the field ice carried us southward about 100 miles. This was infuriating, but it was my own fault, and I knew it. Finally we could see the edge of the ice, and we went to work with renewed vigour. But our luck continued bad. Twice I thought we were clear of it, and each time the current brought us back, surrounded us with the white, low-lying mass. We were beginning to wonder whether we would ever get out, when it breezed up, with intermittent squalls. We escaped all right then, but our course took us into dangerous shoals. They were unchartered and we never knew when we would feel her check her way, and we would hear the sea rushing in through a gaping hole in the hull. I was morally certain we would lose the Morrissey before we were through, and yet, by the luck of Neptune, we never struck at all. We got another lucky break, too, when we found Kamaktorvik Bay, a place where we could beach the Morrissey and make repairs.

The operation was not an unqualified success. We had to do the job on one tide, and that gave us too few hours for work. Everything possible was all ready when we put her on, but even so the job had to be hurried too much. The ice had split the sleeve of the propeller shaft, and this gave us a perpetual leak. The shaft was out of line more than it was before, and caused its share of trouble. Well, we had elected to throw dice with the gods of the north, and the odds were against us. I knew all the time I should have played it safe, and next time I did. I’m realizing more and more that you have to take enough chances up here, whether you want to or not without looking for trouble. If I’d realized this a quarter of a century ago, my life would have been far more simple than it actually turned out. Yes, and my hair wouldn’t be as grey as it is, either.

While we were making repairs, those who could be spared made trips to the bottoms of the various fjords in the vicinity, examining the rivers that ran through them, visiting the lakes, which are numerous and picturesque, and the mountains and plateaux, where they made many interesting pictures and sketch maps. They named one lake after Commodore Ford, and another for William F. Kenny of New York. They had all the trout fishing they could use, taking them with flies and rod, and when that got monotonous, harpooning them in a pool upstream. I don’t suppose that better scenery, wilder, grander, and more inspiring than that section of the Torngat country, with the winds and the snow and the fog and the brilliant sunshine and moonlight, can be found anywhere in the world.

But our time here was limited to the time necessary for making repairs, and when the job was done, all hands were called aboard. I watched for a good chance and when it came worked the Morrissey out through Hudson Strait. As far as Big Island we had a good run, but there we ran into a gale that forced us to proceed under sail alone. This did not last long, though, and we had a fine passage to Amadjuak, or at least to a point fairly near it. The going in that mess of islands is too tricky even for a schooner the size of the Morrissey, with shoals all over the place, and as we had a powerboat that would beat her best speed by three knots there was no sense in trying to work her through. Playing it safe for once, I sent the whaleboat in, and it made the trip all shipshape, coming back with David Wark, factor of the Hudson Bay Company at Amadjuak, and his assistant, a chap named Campbell. When I tell you that it had been nearly a year since they had last greeted anyone from the outside world, you can believe that they were glad to see us. Being all alone that way makes you appreciate visitors more than anything else I know. They mean something, then. They do more than bring news of the outside world – the radio can do that. They bring a personal contact with that outside world. There is a big difference.

And so Wark and Campbell made much of the Morrissey. We had the permission of the Canadian Government to use Eskimos on our trip, and they helped us to find one at Amadjuak. His name was Avalisha, and he was a good man, proving it by taking us through some pretty bad fog to Cape Dorset, where we again played it safe and used the whaleboat. I was getting so plump cautious I wouldn’t recognize myself. This time we had other visitors, also of the Hudson Bay Company, these being a Mr. and Mrs. Ewing. When word was first received by them that a vessel was near they had thought we were the supply ship Nascopie, but on the very afternoon the Morrissey arrived there we heard over the radio that the new steamer Bay Rupert had been lost on a rock off Cape Harrigan, and that the Nascopie had been ordered to transfer her supplies at Chesterfield and return immediately to Montreal for more. This caused a great deal of worry among the agents, apart from the loss of a fine ship, even though they had enough supplies to tide them over if no steamer arrived with replenishments. When I hear of things like the loss of the Bay Rupert I can’t help thinking how lucky I was to have brought the Morrissey through her various scrapes. There isn’t any water anywhere that is foolproof, but the northern seas are less so than the average. It is much easier to get into trouble than it is to get out of it. We had managed to get out. The Bay Rupert didn’t.

The National Research Council, the Museum of Natural History, and the Museum of the American Indian were interested in tracing a Mongolian strain in the Eskimos, and this seemed like a good place to make tests. I therefore left Doctor Heinbecker, Fred Limekiller, and Don Cadzow with the Ewings, to make blood counts. We left them there, hove up anchor, and steamed on to the Foxe Channel, heading for the Trinity Islands. We learned things about ice on this run. The most intensive lesson in this subject came at Mill Island. The tide there runs at about seven knots, and it whirled those ice floes and growlers around as though they were in a mill race. It fairly made me gasp at times to see that tumbling ocean of white blocks all around us. We had to run under power because of the danger of picking up too much way at a dangerous time under sail, and by dodging and retreating and advancing, steering a course that would make an eel dizzy, we managed to keep afloat, and to work into a harbour. We were so glad to find it that we named it after the Morrissey.

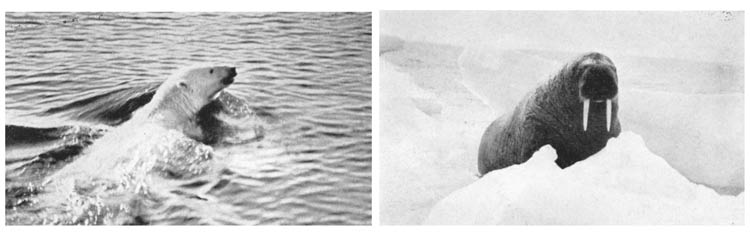

While here, George Putnam, Robert Peary, Johnny Pope, Maurice Kellerman, and Kavaco, an Eskimo, went ashore to take moving pictures of ice running in a tide rip through a narrow channel. They probably would have made an excellent picture had not a polar bear come meandering along. That was more to the point than movies, and Pope and Peary were after it as though they were shot out of a gun. Robert, especially, reminded me of the young Newfoundlanders who grow up to be seal and fish killers, and who spent their youth running and jumping from one ice cake to another, enjoying it the more as it became tricky and dangerous. Those boys used to catch the Devil from their families when they miscalculated and fell in, but that was how they trained their bodies and eyes to get around on the frozen pans and across open leads. Without that experience they could never hope to come through the dangers of seal killing.

Robert, like his father before him, had been brought up around boats, and had a natural gift for working on ice. He could jump from one pan to another, using the seal bats, short, gaff-like hooks, as though he’d been born a Newfoundlander. Johnny didn’t have Robert’s training, or his ability, either, but he was smart and athletic, and he caught on very fast. Between them they got near enough to the bear to use their rifles, and that was the end of the chase.

We got another bear after we worked out into Foxe Channel again. Or maybe he got us. It’s a matter of opinion. We lassoed him, the idea being to get him home alive, and hoisted him on deck. It wasn’t until his paws touched the wood that we realized a mistake had been made. There was no check line for keeping him in one spot. He realized this about as soon as we did, perhaps a second sooner, and in two more seconds he had the deck all to himself. He hadn’t taken kindly to being brought aboard in such an undignified manner, and he wanted to do something about it. The result was that the rigging was pretty well crowded with parties eager to rise in the world – and the higher they rose above that snarling devil on deck, the better they liked it. He had us fairly treed, and I don’t know what would have happened if the mate had not found the after companionway nearer at hand than the rigging, and had gone below. He picked up the 45.70 Winchester rifle, stole up on deck, and polished off our visitor with one shot. That bear, baffled in his efforts to get us, had taken it out on the rail, and the marks left by his teeth are on the Morrissey to this day. Whenever I look at them I think that the worst bucko mate that ever lived would have had no fault to find with the way our crew went aloft that day.

Foxe Channel, where all this happened, was named for Captain Luke Foxe, who discovered it in September of the year 1831, more than a century ago. He reported that he had been 55 or 60 miles north of Cape Queen, but this was later found to be wrong. However, he had made Foxe Channel, and I don’t know, nor does anybody else, how he ever managed to do it at that time of year with the kind of vessel he had. He had no power but his sails, of course. His navigating instruments were crude and uncertain. There were no charts. He and his crew had no comforts – inadequate supplies. Why, my dear man, explorers today live a life of luxury compared to those old-timers. And their success is one of the mysteries of the sea.

But then, if I’ve learned anything in half a century on the ocean, is that anything, no matter how improbable, can happen on salt water. Think how unlikely it is that a man washed off his vessel’s bow by one wave will be washed aboard again in the stern by another. And yet it has happened, and happened many times. I have known things to come about that made the case I have just cited look like a good bet. And Luke Foxe’s trip was one of them. You’ve got to hand it to those old sea dogs. They played a harder game than we do, so they had to dare more. They must have had as many lives as a cat.

I guess the Morrissey has, too, for she has had her troubles. A new set of difficulties lay ahead, and we speedily caught up with them. We were in waters about which little or nothing is known, up around Cape Dorchester, and George Putnam asked me what I wanted to do. I thought awhile, and finally brought up the idea of the Spicer Islands. A number of years ago Captain Spicer reported a group of islands, giving their position near the Strait of Fury and Hecla, and it was my idea that he was all wrong. Subsequent expeditions had found no trace of them, and I wanted to go to that position and see what I could find. George agreed that this was a good idea, but he wanted to stay where he was, to make some pictures, and do some hunting and exploring. The upshot of this was that I left his party with the whaleboat, and made sail northward.

But as we sailed, something made me uneasy about the whaleboat, so we retraced our course. At least, we tried to cover it, and might have fetched port all shipshape if it hadn’t been for the fog. Fog, did I say? It was super fog, so thick you could bite chunks out of it. We missed the entrance to our anchorage and found ourselves just about in the middle of nowhere. We were lost, all right, and I knew it was a hopeless job to find the harbour until it cleared. What I wanted to do was to keep out of trouble, and I couldn’t even do that. I ordered the leadsman out, and he got four fathoms. That wasn’t as much as I’d liked, but it got worse and worse, and I wore ship. It didn’t help any. We kept sailing around trying to find water deep enough to take us out of there, but it was no use. Every way we turned the result was the same.

Then our keel bumped a couple of times. That was enough for me. I anchored right away and sent up a prayer to all the gods I could think of that it was low water. The rise and fall of the tide up here was 40 feet, and if it was quarter tide, the Morrissey was going to go aground. It turned out to be about half tide, and we were on for fair. You could have walked around the Morrissey and not wet your feet. We were on rocky bottom, and once more I went through that bad moment when I figured I was going to be out a schooner. If she went, the chances were we would go with her, too.

Well, sir, the only thing to do was to lay out the heaviest kedge I had, with about 60 fathoms of new five-inch Manila hemp, astern. I knew that when the flood tide came, and the Morrissey floated, she would be swept all over the place at the end of her anchor line unless we could hold her with the kedge. I had small desire to have her bottom scrape over those rock ledges. If the kedge held, we were all right. If it didn’t – hell, as a sea captain friend of mine once said, “You’ve only got to get your neck washed once.” The only thing we could do was wait. We couldn’t see a blasted thing, and that made it worse than ever.

But after what seemed like 10 years I could hear a roaring sound out in the fog beyond the bow. Nearer it came, and nearer. I knew it was the tide, and it sounded bad. We strained our eyes at that grey-black pall, trying to see what it hid. As a matter of fact, we never saw anything until it hit us, and that didn’t take long. It was a solid wall of water, dead black beneath the foam and spray. Six feet high it was, if it was an inch, and it might have been more than that. I remember I jumped to the wheel, never thinking about the anchor or kedges. It’s funny how you react in cases like that. The Morrissey began to straighten up at once, and in no time at all we were almost clear of the bottom.

The force of that tide snapped the five-inch kedge line as though it were a thread. We weren’t kept in suspense on that, at any rate. The stern went around in one wild swerve, and the Morrissey never took a worse beating than she got right then. The water rolled her keel over rocks in a way that jarred her from keelson to trucks. I could hear the groaning of timbers, the splitting sound of wood strained beyond its strength. When we hit, she trembled the way a steamer does when the bridge rings up full speed astern. And that damned fog shut us in so we couldn’t see a thing. Not to be able to see was the worst thing of all, for we couldn’t direct our energy intelligently when we had no idea what our position was. Even if we had been free and clear we wouldn’t have known where to go. In fact, the last thing we wanted was to be free and clear.

After taking an awful pummelling, the Morrissey brought up to the anchor with a jerk that put the martingale clean under water. And it stayed under, too. None of us knew what was going to happen next. The kedge had let go, and apparently the Morrissey wasn’t going to founder, although she was leaking badly, and I had the pumps manned. But if the anchor chain parted we would be swept into water shallow even at the flood, and onto reefs that would tear the bottom clean out of her. My God, how that tide ran. We dropped the log over the stern, and it registered seven knots. That is good speed for a vessel like the Morrissey under sail in a smart breeze.

All this time there had been nothing to do but pray. Now we got into action. As soon as we decided that the anchor would hold, we found that the tide had another trick up its sleeve. It brought the ice in with it, growlers and floes. And, my dear man, ice floes the size of a city block moving at a speed of seven knots are dangerous playthings. If one hit us squarely, it would mean that we had gained little by escaping from earlier difficulties, for if it didn’t break us into pieces then and there, it would sweep us away onto the reefs.

I was at the wheel, never having left it, and I had things to do. I stood there, peering forward, and not a damned thing could I see beyond the foremast. If Davy Jones’s locker is half as dark as that place, I don’t want to go there, and you may lay to that. The lookout on the bow would sing out that a big floe was standing in, and to get over to the port quick. I’d spin the wheel hard over, and the Morrissey would sail herself as far to port as the anchor chain would permit. The water stream on the rudder from the tide was the same as though we were underway, and the schooner handled beautifully. We had to risk breaking out the anchor. It was another case of taking a long chance in preference to waiting for sure destruction.

I was at the wheel for several hours, listening for the hails from the lookout on the bow. I couldn’t see him. He’d yell to swing her to starboard, or to port, and I’d do it. Staring out in the murk, I’d see a low, dull mass of tumbled ice sweep by us, only a few feet away. Stray growlers bounced off the hull, shaking us up badly. The water was as black as ink, and under that fog the ice didn’t look white. It was a dirty grey, and as ominous as the derelicts it resembled. And all the time no roar of wind, no noise but the crunching of ice and the slapping of waves against the hull. Wind never yet bothered the Morrissey. I don’t believe the storm ever blew that could get her down.

But this was worse than any storm I ever saw, and it was the most terrible night I ever spent. We were wet and tired and cold, and we never knew when we wouldn’t be able to clear some big floe. I thought we were gone once, when the tide brought one right down on us. I put the wheel hard over, but it didn’t look as though we could escape. And the outer edge of it got us, forcing us aground until we were at right angles to the tide. We heeled over against it for a minute, hearts in our mouths. And then it slid by, and was gone in the fog. Believe me, things moving at seven knots are going at quite a clip, and that wallop almost finished us.

But finally the tide lost some of its force. The current slackened, and things slowed down to a walk. The ice was still working in, but slowly, and I breathed easier. Maybe we were going to get through all right. At the top of the flood the lead showed 36 feet of water where we had walked at the ebb. Now was our chance to get out, and I sent the whaleboat away at daylight, with a rifle to answer our foghorn, and it returned in half an hour to report that it had found the way out. We found that the engine would still work, and that our propeller was still there, so we steamed out. The fog had begun to thin a little, and then 10 minutes after we left our anchorage it cleared. After that it was easy to find where we had gone wrong, and to get to our own little harbour.

The whaleboat went back and recovered the kedge line, and that was the end of our adventure. We found later that nine beds of timbers and several of the planks had been stove in by the buffetting we took, but I thought we had come out of it pretty damned well, all things considered. To tell the truth, I’m free to admit I wouldn’t have given a torn spinnaker for our chances of coming through when those Arctic subway expresses were roaring down on us out of the black fog.

George’s whaleboat, the cause of all the trouble, was not at the anchorage, so I waited awhile and then, leaving a note telling what had happened, hove up and shoved off again for a look at the Strait of Fury and Hecla. The Morrissey wasn’t in too bad shape to continue her cruise, and it was better to be doing something than just sitting there and twiddling our thumbs. I figured that George would know the engine was pretty much on the bum, and would retreat to Cape Dorset without waiting for us. In any case he could make Lake Harbour, where he was sure to get a vessel, and perhaps meet me coming in. My own idea, everything considered, was pretty ambitious. I planned to go through the strait and if possible to go around Baffinland, picking him up at Dorset.

Our course took us up the Foxe Basin, and we had tough going. However, we weren’t bothered by ice, for the ice bridge at the western end of the strait doesn’t break up until late in the season, if it ever does. Anyway, the ice in Prince Regent Inlet doesn’t work out to the southward, but goes north, which must make it a most difficult piece of water in which to navigate. We didn’t get that far, for the water was shallow, and we used the lead constantly, having a lot of fog as an added handicap. I am certain that we went into waters that had never before been creased by the keel of a vessel, but we found early that there was no hope of attaining our objective.

In the course of our cruise we reached the location given for the islands by Captain Spicer, and found nothing but a waste of water, enough water to float the navies of the world. I believe that he mistook the flats of the east side of Foxe Basin for an archipelago. If he actually discovered any islands they later sank beneath the surface of the water, for they aren’t there now.

Having checked up on this, we worked up into the beginning of the strait, only to be checked by a northwest gale. We anchored offshore in 12 fathoms of water, but it became too rough for comfort with the tide running against the wind, and holding us broadside to. So we hove up and steamed into the lee of the land, anchoring a quarter of a mile offshore in seven fathoms. The bottom was tough mud, and we rode without difficulty to one anchor with 60 fathoms of chain. And yet it blew so hard that sand and small pebbles were carried onto our deck.

The gale blew itself out the next day, and we sailed back to our rendezvous with the whaleboat. It was there waiting for us, and pausing only to take it aboard we set sail for Cape Dorset, entering the harbour the next afternoon. Doctor Heinbecker, Fred Limekiller, and Don Cadzow were there, and they were very anxious about us. Their faces were a study in relief as we hove in sight. Our company was complete again, and I determined to beach the Morrissey. The sleeve of the propeller shaft was leaking badly, the propeller itself was in bad shape, and the oakum needed to be pounded into her seams aft. I found a likely spot, and put her on at high water, or a little below it, to give us sufficient margin for getting off again.

Everything was ready for a quick and a good job. The crew had rehearsed what was to be done, the handling of tools, tackles, the shaft, the propeller, and the caulking hammers. The result of this was that the whole operation went like clockwork. It was as neat a job as was ever done on the Morrissey by what you might call the amateurs, but I knew that we were in for a repair bill when we reached home. The Morrissey floated in fine shape, and we headed south, stopping only at Port Manvers and Turnavik, with a good passage to the Strait of Belle Isle. There we met up with a southwest gale that put us in at Red Bay, where Doctor Grenfell has a mission. We concluded our cruise at Sydney, shipping our specimens and material to New York via a freight car. I had about decided to take the Morrissey off seal hunting, and wanted to stay at Sydney to get conditioned for such a venture. This came to $3,600. We had trouble getting a good ice propeller, but finally succeeded, and in addition fitted a new steel shaft. I put more sheathing on her, renewed the sternpost, using Douglas fir instead of oak, which was expensive and hard to get, and replaced the planking stove in when she was on the rocks. The engine was overhauled and the reversing gear and clutch renewed.

I didn’t see how I could make enough hunting seal to pay for these repairs, and so when Harold MacCracken telegraphed me that he was going to the northern Pacific, visiting the Aleutian and Seal Islands, Cape North, the Siberian coast, Wrangell, Herald Islands, and Point Barrow, and asked if I would care to make the cruise in the Morrissey, I wired back that I would. We were to leave New York in February, and the prospect looked good to me. Major Brown, head of the Nomad Lecture Bureau, which had mapped out a tour for me, managed to get cancellations without loss of money, and everything was all set. The Morrissey had something to do, and some place to go, for another year.