Lena Pittman (Dunnigan Papers, MARBL, Emory University)

Frederick Douglass once said, “Do not judge me by the heights to which I have risen, but by the depths from which I have come.”

My father, as the story goes, was the grandson of Jack Allison, a plantation owner. Grandpa Jack (as we called him) was never married but sired a son named Alex by one of his slaves. It is not known what happened to Alex’s mother, who most likely either died or was sold down the river. Grandpa Jack took Alex to live with him in the big house, rearing him as if he were a legitimate child of his own race. In due time, Jack bought another attractive, half-Indian, half-Negro slave named Martha to serve as his housekeeper and concubine. Along with this purchase came Martha’s own little girl named Alice, who was fathered by her former master. Little Alice (for whom I was named) also lived in the big house, along with her mother, Martha, Massa Jack, and his mulatto son, Alex.

Jack was often charged with the offense of adultery and fornication by county law enforcement officers. He would always pay his five-dollar fine and continue to cohabit with his black paramour. These charges were made so frequently that Grandpa Jack adopted a policy of voluntarily riding into town on horseback the first of each month to post the five-dollar fine before the arrest was made, then go right on living with Grandma Martha.

As time went on, the union between Jack, the white plantation owner, and Martha, the colored slave, produced six children. In the meantime, the two older, mulatto children, Alex and Alice, who as stepbrother and sister shared the same house but were not actually blood relations, became infatuated with each other and were married. To this union were born seven children including my father, Willie. All of these children were permitted to attend elementary school until at least completing sixth grade. The Allison family stayed together and cultivated the farm—not as master and slaves but as one big family—until Grandma Martha passed away.

My mother came from quite a different background. Her story, as she related it to me many times, went something like this. She, with an older sister, Lou, and a younger sister, Annie, lived on a farm with their mother, Minerva, and their grandfather, Jake Pittman. The girls knew nothing about their fathers since their mother was never married. Because my grandmother had three children out of wedlock, she was considered a “softy” by men of her acquaintance and described by neighbors as being incapable of taking care of herself. In addition, she had a speech impediment that caused people to brand her as mentally retarded or, as they called it, feeble-minded. Even her father treated her in this manner, never discussing any business matters with her, never giving her any responsibility or ever allowing her a chance to develop her mental capabilities.

Grandpap Jake (as we called Grandma Minerva’s father), was a strong-willed, hardworking, shrewd businessman. Only a few years out of slavery, he had managed to acquire a sizable farm, with mules, cows, a wagon, and other farm tools such as plows, harrows, and the like. The entire family worked with him on the farm, helping to cultivate the two principal crops, tobacco and corn. The children were never allowed to go to school or any other place. Once a year, on circus day, my mother recalled, Grandpap would load the three grandchildren and their mother into the wagon and carry them to town to see the circus.

In the fall when the tobacco was sold, he would buy each of the grandchildren a pair of shoes, which they wore for the entire winter. If the shoes wore out or became too small before warm weather, the girls would have to wrap their feet in rags because there would be no more shoes until the next year. They all went barefoot during the entire summer.

One thing Mama remembered most vividly about her grandfather was that he was “saving.” You might call him sort of a pack rat, she said. He would pick up everything he saw on the road or in a field, be it an old crooked nail, a rusty screw, a tap, a bolt or nut, or even a twisted horseshoe. He piled all of this junk beneath a huge poplar tree in their yard with the warning that “these things might come in handy someday.” From this lesson my mother learned to be economical and never wasted anything. This was also a trait she passed on to my brother and me.

When Grandpap Jake died, he left his family completely helpless. None of them knew what to do or which way to turn. My mother was ten years old at the time, but she remembered white people coming in and taking everything they had. One white man would come in and take a mule, saying, “Uncle Jake owes me and I’m going to take this mule for the debt.” Another would come in with the same explanation and take a cow. Still another took the wagon, and so on until everything was gone, even the farm. None of them showed any papers or other evidence that “Uncle Jake” owed them anything. It was then that Mama realized that her mother didn’t know what to do and that each child had to look out for herself.

So, without any family consultation or knowledge of what her mother and sisters planned to do, she struck out on her own. Donning her one good dress, she started walking down the road toward town, stopping at every house she passed, asking if they wanted to hire a little girl to help with the housework. She had reached the edge of town before anyone showed an interest. This was the Wilson family who showed a willingness to hire her to take care of their baby, Cyrus. “How much do you want for your work?” Mrs. Wilson asked.

“Vittles and clothes” was the reply, and with this, she was hired.

First, she was taught to care for the baby. As time went on, she was given additional chores such as cleaning house, washing dishes, doing the laundry, and finally cooking. Mama recalled how pleased she was when Mrs. Wilson bought calico and made her some new dresses. As she grew older, she was also taught to sew and had to make her own clothes. She remembered how she used to cry if she sewed the seam wrong and was made to rip it out and do it over again until it was done right. She thought Mrs. Wilson was awfully mean but was later proud that she had been taught to do her work right.

Mama was an excellent worker but was never allowed to spend much time in school. Mrs. Wilson would let her go to school only now and then, she said, until she finally reached the third grade. Mama often said, “About all I learned was how to write my name. I’m an awful poor reader. I wish I could read good.”

My mother had reached her teens and was doing all kinds of housework before she received any wages. She was quite shy, but one day she asked Mrs. Wilson for a little spending money. “Don’t you think my work is worth something?” The “madam” agreed to allow her fifty cents a week. That amount was gradually increased until it reached two dollars per week, the amount she was receiving when she left the Wilson household as a grown young lady.

Lou and Annie, my mother’s sisters, each found jobs with white families, but she never knew how it was managed. They both died soon after at very early ages.

The (white) Albert Wilhelm family, who owned the farm adjoining my great-grandfather’s and who took over his land after his death, later deeded one acre back to my grandmother and built her a one-room cabin with a lean-to kitchen. They allowed her to do odd jobs around their house for food and a little spending money, an arrangement that lasted until her death. As she grew older, my mother realized that the Wilhelms must have taken her grandfather’s land unfairly or they never would have been so generous as to later give a plot of land to her mother and build her a house.

Growing into young womanhood, my mother became dissatisfied working for, and living with, the Wilsons. She wanted a social life, and the opportunity to be with young people of her own age and race. She was anxious to attend church and participate in other social activities. So she left the Wilsons and obtained a cooking job with another white family in town. She got a room with a colored family and helped the landlady with laundry work at night to pay for her lodging. She began to go out with fellows like other girls her age were. Unfortunately, she also became pregnant. When Richard was born, she arranged for her mother to keep him while she continued working.

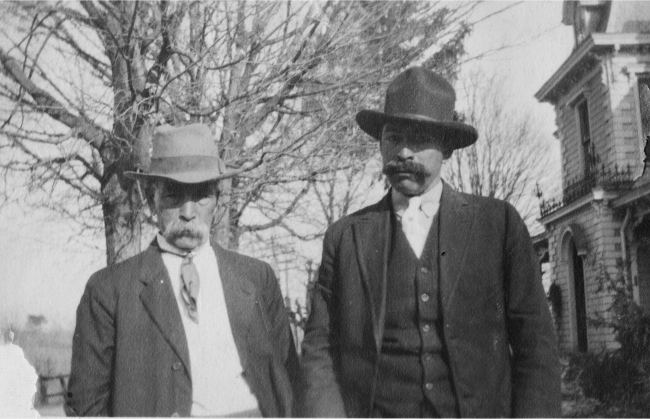

Willie Allison (right) with his father, Alex Allison (Dunnigan Papers, MARBL, Emory University)

Richard was four years old when my mother, Lena Pittman, met and married my father, Willie Allison. A tall, rather attractive, light brown woman with high, Indian-like cheekbones and short, reddish-brown hair, my mother had accepted my father in matrimony against the wishes of her mother. My father was a tall, medium-built, handsome man with fair skin, straight black hair, and a heavy mustache, who, despite his meek, kind, congenial personality, was rejected by his mother-in-law for no reason other than his color. My grandmother had the notion that “them yallow Allison niggers think they’re better than my Lena and I don’t want any part of them.” Nevertheless, the young couple added another room onto Grandma Minerva’s cabin and went to live with her. They were married three years before I came into the world. And it is from this point that my story really begins.