Blacks converged on Washington from all over the country for the opening of the Eightieth Congress, soon dubbed by Truman the “do-nothing” Congress. (Atlanta Daily World, January 5, 1947)

I began my job as chief of the Washington Bureau for the Associated Negro Press on the first day of January 1947. My first assignment was to cover the potential ouster of Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi from the U.S. Senate for misconduct.1 I was fairly familiar with legislative procedure and with the Capitol building, having often lobbied with a delegation from the Southern Conference for Human Welfare2 for passage of anti-poll-tax legislation and an antilynching law, two bills of major concern to that organization. But I knew nothing of press operations on Capitol Hill.

On the opening day of Congress, I secured from my Kentucky senator a pass admitting me to the visitors’ gallery. Upon arrival, I found a long line waiting for seats in the already overflowing gallery. For hours I stood in this line, which moved only when a few people left the gallery, making room for a few others. I became very disgusted and anxious to get inside so that I could get to work on my assignment. I was completely unaware that it was against Capitol rules for spectators to take notes in the visitors’ gallery. When I discovered this, I realized that the visitors’ gallery was not an appropriate place for reporters, anyway.

Blacks converged on Washington from all over the country for the opening of the Eightieth Congress, soon dubbed by Truman the “do-nothing” Congress. (Atlanta Daily World, January 5, 1947)

While standing in line, I noticed a number of newsmen entering and going up a back stairway that was securely roped off with the usual red velvet ropes so commonly seen in places of dignity around the nation’s capital. This stairway was guarded by Capitol police. The reporters would step up, show their passes, and be admitted. I saw no reason why I shouldn’t do that. So I stepped up to the stairway, only to be stopped by the guards and asked where I was going.

“I’m a newspaper reporter,” I explained, “and I’m going wherever those newsmen are going.”

“But this is reserved only for reporters of accredited newspapers,” one policeman replied.

“I’m a reporter for an accredited news bureau,” I argued, proudly producing my newly acquired ANP press pass for inspection.

“Even with that,” the other guard chimed in, “I don’t think you belong up there. But I’m going to let you through. If you have no business up there, they’ll send you back, anyway.” With this he unsnapped the rope and allowed me to pass.

At the top of the steps, I opened a door marked “Press Gallery” and walked in. To my surprise, I was in a large suite of rooms completely equipped with all types of apparatus needed by reporters. There were rows of typewriters and shelves filled with reference books, dictionaries, and congressional registers covering many years. A Western Union machine was ticking away in one corner of an adjoining room. One whole wall was lined with telephone booths. Through an open door, I could see another room full of radio and television equipment. Still another room was furnished with comfortable couches and easy chairs for relaxation.

Press releases were piled high on a little table, surrounded by stacks of copy paper, carbon paper, Western Union blanks, letterheads, and envelopes. The main door led into the gallery overlooking the Senate chamber. Rows of circular seats were provided for reporters to watch the Senate in action. This is indeed a reporter’s haven, I thought, as I gazed around in awe. Suddenly I was facing a gallery official who politely asked if there was anything he could do for me.

I explained that I was a reporter assigned to the Bilbo hearing and wanted only to see what was going on inside the Senate chamber.

“No one can observe from the gallery except accredited Capitol reporters,” the man explained.

“What does one have to do to become an accredited Capitol reporter?” I asked.

Without specifically answering my question, the official stated that they were not accrediting any more reporters because they already had more members than they could accommodate in that space.

“Are there any Negro reporters accredited?” I asked.

He gave a negative answer, explaining that there were certain qualifications. If a reporter met those qualifications, he could apply for membership. His application would be reviewed by the standing committee of the gallery, and if it met the requirements, his membership would be approved by the committee.

I asked for and received an application, which I later completed and submitted.

Weeks passed, and I received no word regarding my application. When I called about it, I was told that the standing committee had not yet acted on it. After more weeks passed, I called again and received the same answer. After a while, I began to make personal visits to the Capitol to inquire about the status of my application, probably making a nuisance of myself. Finally I was informed that I did not qualify for membership since applicants were required to represent daily papers.

To pacify me, I was given another application for membership in the Periodical Gallery. I submitted it and ultimately was notified that I did not qualify for membership there because that gallery, they said, was exclusively designed for magazine writers and I was representing weekly newspapers.

The Louisville Leader (July 5, 1947) was one of the half-dozen black Kentucky newspapers for which Dunnigan worked before moving to Washington and breaking through the first of many barriers to the black press as Washington bureau chief for ANP.

The fight for membership continued, with various organizations and the newspaper guild getting into the act. After a time, the Senate Rules Committee, chaired by Illinois Republican senator C. Wayland (Curley) Brooks, held hearings on the matter. The upshot was the committee ordering that the rules of the gallery be changed to admit representatives of news agencies.

A few weeks later, Louis Lautier, representing another news agency—the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA)—was notified that he had been accepted in the Capitol press corps, thus making him the first Negro member. Percival L. Prattis was admitted to the Periodical Gallery a few days earlier as a representative of Our World magazine.

I was disturbed about Lautier being admitted before me since I had vigorously carried the fight, but I never questioned it. Sometime later, however, I found out that action on my application had been delayed because ANP director Claude Barnett was a little slow in sending in a letter of recommendation.

The office of the Illinois senator sent this group picture of Senator Charles Wayland Brooks (second from right), chairman of the Senate Rules Committee; Griffing Bancroft, chairman of the Senate Press Gallery Standing Committee; Alice Dunnigan of ANP; and Louis Lautier of NNPA to Negro newspapers around the country, most of which gave the rules change a good play. (From Alice Allison Dunnigan, A Black Woman's Experience—from Schoolhouse to White House, [Philadelphia: Dorrance & Co., 1974])

When I had contacted Mr. Barnett regarding the need for such a letter, he was somewhat skeptical about recommending me because I was “daring to rush in where angels feared to tread.” “For years,” he wrote me, “we have been trying to get a man accredited to the Capitol Galleries and have not succeeded. What makes you think that you—a woman—can accomplish this feat?”

It was only after quite an exchange of correspondence and telephone conversations that Barnett reluctantly sent a letter of recommendation, and soon afterward, in June 1947, I became the first Negro woman to receive Capitol accreditation. My acceptance received widespread publicity, and the Republican-controlled Congress received credit for opening the Capitol Press Galleries to Negro reporters.

Lautier and I were the only Negroes holding accreditation to the regular galleries for a number of years, until Ethel Payne came to Washington in 1953 to represent the Chicago Defender and qualified for accreditation because of her affiliation with the new Chicago daily paper. (Roscoe Conkling Simmons, the first Negro writer on a daily newspaper in Washington, D.C., the Times-Herald, was accredited to the Capitol Press Galleries in January 1951 but died four months later.)

One of the people who took me under her wing and coached me on the do’s and don’ts of Capitol reporters was one of the nation’s best-known journalists and one of the nicest people I have ever met—May Craig, who represented several Maine newspapers. She gave me tips on how to win friends, introduced me to many of hers in the national press and Congress, and helped me immeasurably in winning acceptance and respect on the Hill. She was also instrumental in my becoming the first Negro member of the Women’s National Press Club. Although it took eight years to happen, she had initiated and supported my membership from the start.

After being credentialed at the Capitol, my next goal was accreditation to the White House to cover presidential press conferences. Lautier was already a White House correspondent—the only black one—having succeeded NNPA representative Harry McAlpin, who in February 1944 had become the first Negro in the White House press corps. I took on this fight alone, without assistance from my employer, by going to the White House to appeal for more Negro representation among the White House press. In a conversation with Charlie Ross, President Truman’s press secretary,3 I said, “The Republican Congress has lowered the barriers against Negro reporters in the Capitol Galleries. What is the Democratic administration going to do about admitting more Negroes to the White House press corps?” Ross’s advice was to send a letter to the White House requesting accreditation. I did, and I received the coveted White House press pass in short order and without any problems. Later, without further effort, I became a member of the White House Correspondents Association.4

Next I sought membership in the State Department Press Association, of which my predecessor, Ernest Johnson, had been a member as well as James (Jimmy) Hicks and Louis Lautier, both of NNPA. In August 1947, I became the first woman of my race to receive membership in this group.

I had no further trouble receiving accreditation until I applied for a metropolitan police pass and was called in for an interview by the accrediting officer, who was connected with the Associated Press (AP). He informed me that an objection had been registered against my receiving credentials. The complaint came from a reporter for the Washington Afro-American newspaper, who contended that I had no need for a local police pass since I represented a national news agency. He assured the accreditor that one Negro police reporter was sufficient to assimilate news of interest to Negro readers. When the accrediting officer learned that I held a Capitol press pass, he issued my police credentials without further ado, making me one of the few women at the time to hold a Washington police press permit.

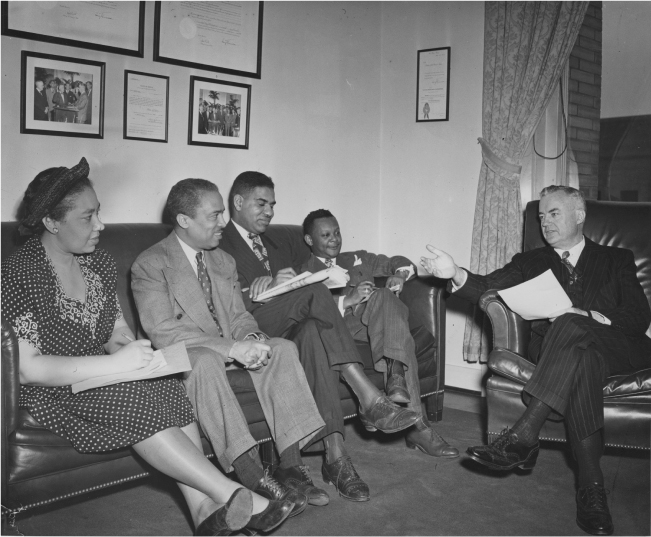

In the 1940s, it was not unusual for Dunnigan to be the only female reporter in an interview. Here, she is interviewing Illinois Republican Charles Wayland Brooks with Louis Lautier (NNPA), Al Sweeney (Washington Afro-American), and Chick Webb (Pittsburgh Courier) in 1948. (Dunnigan Papers, MARBL, Emory University)

Another necessary pass for newswomen in those days was one that admitted the holder to the First Lady’s press conferences, which were held in the East Wing of the White House. (The president’s press conferences were held in the West Wing.) I had no difficulty obtaining this pass.

It didn’t take me long to establish contacts in each of the executive departments whom I could depend on for news tips unavailable to the general press. This was especially true after top Negro executives (commonly known as the Black Cabinet) became confident that I would protect my sources. These few Negroes holding high-ranking government posts were serious about improving conditions for black people. When they were unsuccessful in their attempts to right a wrong in their respective departments through negotiations with superiors, they would discreetly leak the situation to the Negro press, even at the risk of losing their jobs if discovered doing so. I had many exclusives from these sources because I made it a practice to visit the agencies periodically, digging for information and usually getting it. The sources also realized that the story would get broad coverage in newspapers across the country, often leading to pressure on politicians from Negro communities to solve a problem to the satisfaction of black voters.

My work days had no hourly limit, and my work weeks had no end. Day and night, Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays, I was on the job if there was the possibility of a news story breaking anywhere, from the upper chambers of the government to Embassy Row, the slums or city streets, sports arenas, social circles, or halls of justice. These efforts produced a vast number of exclusive stories that appeared under my byline in newspapers throughout the country. Soon ANP was said to be doing a better job than ever before of dispersing firsthand, on-the-spot news to its clients. Previously, it had been sending out so many rewrites from big city dailies such as the Washington Post and the New York Times that some of its clients had begun to refer to it as the “Associated Clip Service.”

While some of ANP’S clients expressed delight to see the service come alive, the accolades brought me no additional compensation, and I was still making difficult choices regarding living expenses, the cost of cabs around the city, and trying to make a good showing. Contemporary fashion trends created a challenge in the latter regard when hemlines suddenly dropped and I had no cash for new clothes. One of my contacts in a well-known women’s organization told me later that I paid a price for that when some of its middle class, socialite members objected to my receiving an award from the organization on grounds that I wasn’t representative of black women because I went to the White House in “those old short dresses” and wearing neither a hat nor gloves. I was cut deeply by those remarks because I’d done many hours of volunteer work for the organization, and I wondered how its members could take such an attitude toward someone who had worked so hard to pull herself up by her own bootstraps.

I told my confidant to go back and tell those women that since a presidential news conference is not a reception, one does not go there attired as if attending a reception but rather to work, and I would look pretty silly going there in anything but simple office clothing. I never had further confirmation of my informer’s report, but neither did I ever receive any public recognition from this organization, although I was honored by other women’s organizations, among many other groups.