Dunnigan had the lead article in many ANP newspapers when concert star Paul Robeson was denounced as a Communist. (Kansas City Plaindealer, July 22, 1949)

Monday, March 1, 1954, started out as a quiet—indeed dull—day on Capitol Hill. I was just one of the reporters and columnists roving the Capitol corridors in search of any tidbit of choice news around which to build some copy.

Then all of a sudden—“Boom! Boom!”—the fireworks started. Blazes burst forth from the southeast corner of the visitors’ gallery, where a woman stood waving a Puerto Rican flag in one hand and shooting a gun with the other as she shouted something that sounded like “Vive Puerto Rico!” She was flanked by two men who were also firing pistols, sending bullets flying wildly through the chamber. Some hit the ceiling, while others found a target among the congressmen who at that moment were taking a standing vote on a resolution to permit debate on a bill authorizing continuation of a program admitting Mexican farm laborers to enter this country for temporary employment.

When the shooting ended, five congressmen lay wounded, one seriously, in pools of blood on the House floor. Reporters rushed from the press gallery down to the floor for a closer view. All were permitted except me. I was stopped by Capitol police until I fumbled in my purse and found my press pass. Later, my colleagues laughed that because of my complexion, “they thought you were one of the Puerto Ricans!” With that, I acquired from the gallery the nickname “Miss Puerto Rico.”

Despite being delayed, I rushed to the telephone immediately following the shooting and called my home office in Chicago to report the incident. In his usual slow, unperturbed manner, Mr. Barnett calmly asked if either Dawson or Powell (the only two Negro congressmen at that time) had been shot. When I said no, he asked, “Then why are you calling here? You’ve got no story.”

His attitude deflated my ego beyond imagination. I thought I did have a story—the story that both Negro congressmen escaped injury when the Puerto Ricans shot up the Congress. There was also another story, one regarding William Belcher, the Negro doorman at the House Gallery who actually captured one of the gunmen and was injured in the scuffle. After collapsing with a heart attack, he was rushed to the hospital for treatment.

A few months later, I covered the nine-day trial. The woman and her three male companions were found guilty of assault with intent to kill, although they denied any attempt to murder. They claimed that their only purpose was to stage a demonstration that would obligate the United States to end the colonial system existing in Puerto Rico and grant the island independence. All were sentenced to long—effectively life—terms.1

President Truman understood perhaps better than anyone the importance of the question of Puerto Rican independence. Two Puerto Rican Nationalists planning to assassinate him had tried to shoot their way into Blair House, where the president was staying during White House renovations, on November 1, 1950. A police officer was killed in the attack, as was one of the Nationalists. The other was sentenced to prison.2

Listening to the testimony of the defendants, I recalled the Panama Canal Zone history of color discrimination imposed by Americans on territories outside of the continental United States. Puerto Rico’s Nationalist Party had grown out of discrimination that penetrated the island during World War I, when the U.S. Army assigned fair-skinned Puerto Ricans to all-white units while their darker-skinned brothers were relegated to all-black units.

As the story was told, a mulatto, a Harvard Law School graduate who was the son of a white father and colored mother, became so embittered at this arrangement that he formed the Nationalist Part early in the 1920s for the purpose of liberating Puerto Rico from U.S. domination.

The Capitol shooting, followed by the lengthy trial, was probably the most exciting as well as tragic incident I covered during my entire journalism career.

By the mid-1950s, the movement of civil rights cases through the federal circuits and up to the Supreme Court necessitated the expansion of my news beat and additional credentials. Once again, the ANP director took a dim view of my application for accreditation to the highest court. Mr. Barnett took the position that I would do well to cultivate a closer relationship with court messengers and persuade them to sneak out to me advance copies of the decisions. This, he felt, would be more advantageous than spending hours in the official press box listening to extended arguments on specific cases.

I was enraged at this suggestion since Negro reporters had fought so hard and long for the same opportunities offered white reporters on these most important news beats. I devoted an entire column to blasting some Negro newspaper executives for insisting on holding onto that “old-fashioned, back-door” method of reporting to which we had for so long been relegated. I didn’t think the papers would publish this scathing column—but they did.

Despite ANP’s lack of enthusiasm for the idea, I had no problem obtaining a Supreme Court press pass and again took my place alongside some of the leading reporters in the country. But I did find it to be the most difficult assignment in my entire press career. Decisions were sent down to the press office every Monday. Sometimes they would be several pages long and others just a single sentence. In order to report on these decisions, one had to know the background of the case. For this, a reporter had to find the appropriate briefs on the library shelves of the pressroom and learn to quickly locate the specific paragraph that outlined concisely the facts of the case. Then the reporter had to translate any legalese into language understandable to the average reader. Since I had no legal training, that job never became a simple routine for as long as I covered the Supreme Court. The experience, however, came with the privilege of being on the spot when some of the most famous lawyers of that day argued some of the most significant cases of our times before some of the nation’s most distinguished jurists.

It was the era of such giants of civil rights litigation as Thurgood Marshall, who eventually became an associate justice (appointed by President Johnson in 1967); James Nabrit, later president of Howard University; renowned constitutional lawyer Charles Houston; and Robert Carter of the NAACP. It was also the decade of landmark school desegregation decisions that, along with the courage of thousands of black men, women, and even children, such as the Little Rock Nine, who put their bodies on the line, led to an enormous change in race relations in this country.

I covered every case involving Negroes that reached the Supreme Court as well as others in the district court, Washington’s federal trial court. It was there that I saw the tears stream from the eyes of Dr. W. E. B. DuBois’s wife, Shirley, as her husband was escorted from a courthouse elevator in handcuffs. It was 1951, and the celebrated eighty-three-year-old socialist, historian, and civil rights activist had been charged with being an agent of a foreign power. Tears welled in the eyes of sympathetic reporters as well, as Shirley described how this grand old gentleman had been fingerprinted and searched for concealed weapons as if a common criminal.

Dr. DuBois was being prosecuted because he spoke out against the use of nuclear weapons and criticized the U.S. government for backing colonial powers at the San Francisco Conference, which established the charter of the United Nations. He had appeared before the House Committee on Foreign Relations in 1949 to urge Congress to vote down the payment of a billion and a half dollars for military assistance to the North Atlantic Treaty Alliance countries, arguing, “This country claims not to have enough money to spend fighting ignorance, disease, waste, or for old age security for its workers, but it is asking for a huge sum to be spent to murder, blind, and cripple men, women, and children abroad and destroy their property by fire and flood.”

After that, the government tried without success to silence Dr. DuBois. In 1951, the government withdrew his passport, denying him the right to travel abroad. Still he continued to lead a group of citizens who claimed to be seeking peace in the world at the time when Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anticommunist campaign was at its peak. This was what almost placed him behind bars. However, widespread publicity, primarily through the press, aroused citizens of the United States and around the world to protest against the prosecution of Dr. DuBois, and finally it was dropped.3

Dunnigan had the lead article in many ANP newspapers when concert star Paul Robeson was denounced as a Communist. (Kansas City Plaindealer, July 22, 1949)

For years, I also followed the trials of another prominent American whose passport was revoked because of his political activities and statements. I wrote a running account of theatrical and concert artist Paul Robeson’s conflict with the government from the very beginning (1948) when he was threatened with a jail sentence for refusing to tell a Senate committee whether he was a card-carrying Communist. Robeson sued in district court in 1950 for validation of his passport, but the court upheld the State Department’s action, and the following year the court of appeals refused to review the case on the grounds that since the passport had expired, the case was moot.

After four subsequent applications for a passport to enable him to fulfill concert engagements abroad were denied, another lawsuit in 1955 brought results, and two years later his passport was reinstated. In the meantime, however, Robeson’s income had suffered and his health had drastically declined. While some of the press coverage of Robeson’s plight had ranged from hostile to at best ambivalent, his wife of forty-four years, Eslanda (“Essie”), an anthropologist, author, and journalist, took some solace in my stories, writing me, “It is such a pleasure to read a dignified story about the Robesons these days. We are sick and tired and angry about the malicious, wholly untrue, deliberately misleading stuff which the press keeps printing about us. I was delighted that it was the Negro press that saw fit to print the truth.”

President Truman’s Executive Order No. 9981, issued on July 26, 1948, calling for equality of treatment and opportunity in the armed forces, also ordered desegregation of schools for children of personnel stationed on military bases. This latter provision, however, had met with resistance from some southern state officials as well as some high-ranking officials in the federal government. I brought this to the attention of President Eisenhower at a press conference on March 19, 1953, shortly after he took office, asking what he proposed to do about segregated schools on military bases. In reply, he made this famous statement:

I have said it again and again: wherever federal funds are expended, I do not see how any American can justify—legally, logically, or morally—discrimination in the expenditure of those funds as among our citizens. All are taxed to provide those funds. If there is any benefit to be derived from them, I think they all must share, regardless of such inconsequential factors as race and religion.4

The president promised to look into this situation and give me a definite reply later. Months passed and nothing more was heard about this matter. Later that year, at the president’s September 30, 1953, press conference, I again reminded him of this situation, pointing out that the Department of Defense had issued a statement that the integration of schools on military posts might be delayed until 1955, and asked for his comment on the proposal. Eisenhower denied any knowledge of this development and again said he’d have his press secretary, James Hagerty, look into it and let me know.

Soon afterward, the president announced that the Department of Defense had set September 1955 as the target date for ending segregation in all schools on military bases. However, all major posts except Fort Benning, Georgia, were reported to have integrated their schools peacefully and successfully long before the two-year deadline, after months of work by the NAACP, Senator Hubert H. Humphrey, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., and parents on the bases who objected to sending their children to segregated schools.

Halfway through the twentieth century, the nation’s capital was still a very segregated city. Some of the many places from which Negroes continued to be barred in the late 1940s were downtown theaters. The National Theatre, the city’s only legitimate playhouse, was closed to both black entertainers and black patrons of the arts. Washington residents rejected the policy and staged picket lines around the theater for months, and in 1947 the Actors Equity Association, the union representing stage actors and managers, stopped its members from appearing at the National Theatre unless it changed its policy. Rather than change, the management in 1948 converted the theater into a movie house. The Department of State found the lack of a legitimate theater in the nation’s capital a source of some embarrassment when noted by foreign visitors. But that was about to change.

In 1950 when the Rock Creek Park amphitheater that became known as Carter Barron Theatre opened to the public, it was on a nonsegregated basis, and President and Mrs. Truman and their daughter Margaret were guests of honor on opening night. The president pushed the button that signaled the start of a beautiful pageant entitled “Faith of Our Fathers,” starring an integrated cast of performers.

During this decade, segregation—at least overt, sanctioned segregation—in public places, including places of entertainment, was finally prohibited in the nation’s capital after a three-year court battle. This Supreme Court decision grew out of a lawsuit brought against Thompson’s Cafeteria in 1950 by three Negroes—Mary Church Terrell, the Reverend W. H. Jernagin, and Geneva Brown—and one white man, David Scull.

Central to the case was the validity of two old antisegregation laws passed in the District of Columbia in 1872 and 1873, respectively. The National Lawyers Guild claimed that these so-called lost laws were still valid, although they had not been enforced since the legislative assembly in D.C. was abolished in 1874. I followed the case from the Office of the Corporation Counsel (the city’s attorney), which concluded that the seventy-seven-year-old laws had never been repealed, through the municipal court, which dismissed the case on the grounds that the laws had been “repealed by implication.” The suit then went to the court of appeals, which reversed the lower court decision. Finally, the case reached the Supreme Court, which in June 1953 upheld the ruling of the court of appeals declaring the “lost laws” still valid.

The decision called for the immediate abolition of segregation in restaurants, hotels, bathing houses, soda fountains, theaters, and other places of amusement. Not more than two hours after the Supreme Court announced its ruling, I was privileged to accompany the plaintiffs to the same Thompson’s Cafeteria for lunch, where we were all served with no problem.

I had been following Mrs. Terrell’s actions since she accepted chairmanship of the Coordinating Committee for the Enforcement of the D.C. Anti-Discrimination Laws in 1949. I saw her in her ripe old age lead the fight to break down discrimination against Negro membership in the American Association of University Women. I watched her march in countless picket lines and make innumerable speeches against discriminatory hiring practices in downtown businesses until her efforts bore fruit and Negroes were finally employed as salespeople in department, shoe, drug, and variety stores.

One store in particular showed its commitment to racial equality by training and employing young Negro women as models for its fashion shows in downtown hotels and other venues. In 1968, I was pleased to see the Hecht Company receive an award for this service, upon my recommendation, from the President’s Committee on Youth Opportunities.5

Mrs. Terrell, who deserves considerable credit for the progress made in D.C. during this era, was born in 1863, the year President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and died in 1954, after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown. In an interview after that historic ruling, she said, “Thank God! I can now die in peace. I have seen the last vestige of segregation wiped from our great nation—in transportation, hotels, and restaurants, in employment and recreation, and now in education.” This grand old lady died a few months later without knowing the struggle, the pain, and the bloodshed that still loomed ahead before black Americans would finally enjoy the harvest of these seminal decisions of the high court. Her life and beautiful work, however, continued to inspire many others who followed in her footsteps. I thought of her as an idol and pledged to help continue the fight she had begun to advance the cause for a better America in the only way I knew how—with the pen, realizing full well the truth of the saying that it is mightier than the sword.

Dunnigan was inspired by the great civil rights leader Mary Church Terrell. (From Dunnigan, Black Woman’s Experience)

I met many firsts on the road to freedom as I used that power to report on both progress and problems along the way. I saw the first Negro employed as an elevator operator in the Capitol complex, the first black man appointed to the Capitol police force, the first African American chef assigned to the Capitol kitchen, the first black man appointed doorman to the Senate chambers (and later another to the House Gallery).6 I interviewed the first black pageboy on Capitol Hill,7 and I covered the commencement ceremony at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1949 when Wesley A. Brown earned the honor of being the academy’s first Negro graduate. Some people today might scoff at my calling these breakthroughs or milestones, but they provided the shoulders on which future giants would stand to wage the battle for true equality.

One of the most distressing situations I ever covered unfolded at the end of the decade in Fayette County, Tennessee, when a small group of blacks, spurred by the voting rights provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, attempted to vote in the 1959 primaries for state and local officials. When news of their effort spread, the whites in the county initiated an economic “squeeze” against those Negroes who dared challenge an eighty-year-old tradition by demanding to vote in what had been commonly known as a “white primary” since Reconstruction.8

The situation worsened after Negroes filed and won a suit against the Democratic Committee in the county, charging that blacks had been illegally barred from exercising their franchise. After this victory, blacks flocked from the farms to the courthouse in Somerville to register.

Irate white landlords became so embittered that they began ordering the sharecroppers off their farms. Merchants refused to sell them food or other goods. Banks declined loans to farmers for seed or fertilizer. Filling stations also denied them gasoline to operate their tractors. Wholesalers and distributors withheld produce from Negro merchants, practically forcing them out of business. Oil companies snatched their gasoline tanks from Negro owners of filling stations. A number of leaders of the voter registration drive or members of their families were fired from their jobs, ranging from cafeteria workers to schoolteachers.

White landowners who refused to join the economic squeeze against Negro voters were subjected to economic reprisal and ostracism by members of their own race. White journalists trying to get the facts about the situation were questioned and harassed by law officers.

Shepherd Towles, one of the few Negro farmers who owned his own land, permitted tents to be placed on his land to house the homeless sharecroppers. The site became known throughout the nation as Tent City, or as some writers dubbed it, Freedom Village.

News of these events and pleas from many organizations, spearheaded by the NAACP, brought shipments of food and clothing from around the country and abroad for the homeless, evicted blacks.

This was another story where I waded in without ANP support, since Mr. Barnett did not agree with my venturing beyond Washington for news. Nevertheless, I gave our clients a series of articles on the entire situation at no cost to the news service, which never asked how the trip was financed. Now I can tell. The tab was picked up by a prominent public relations firm that had as a client one of the nation’s leading oil companies, which was sympathetic to the black farmers’ cause in Fayette County and wanted to come to their rescue but was fearful of reprisals from the other boycotting companies. After getting a firsthand look, the company quietly began to supply gasoline to a Negro filling station owner with the understanding that he would tell no one how, when, or where he was obtaining it.

When the retailer’s tank was filled with gasoline, it greatly relieved the black farmers who owned tractors and trucks. The white landowners were puzzled as to how and from where the gasoline was coming. My mission was to “case” the situation and especially to explore whether the whites had any inkling as to who was supplying the gasoline and whether the black retailer was keeping his pledge to secrecy. As it turned out, the retailer was mum. When I asked him how he got the gas, he replied, “It is delivered on dark, country roads, late at night, in unmarked trucks.” When I attempted to catch him off guard by asking what kind of gas he sold, he quickly replied, “I sell ‘independent’ gasoline. But my friends say I should call it ‘Tennessee squeeze’ gas.”

Shortly afterward, at President John F. Kennedy’s first press conference (also the first presidential news conference telecast live) on January 25, 1961, I asked the new president whether his administration planned to take steps to solve the problem of the people in Tennessee who had been evicted from their homes because they dared to vote in the last election and were now forced to live in tents.

The president replied, referring to the Civil Rights Act of 1960, “Congress, of course, enacted legislation which placed very clear responsibility on the executive branch to protect the right of voting. I supported that legislation.” He continued, “I am extremely interested in making sure that every American is given the right to cast his vote without prejudice to his rights as a citizen, and therefore I can state that this administration will pursue the problem of providing that protection with all vigor.”9

While Department of Justice actions in Tennessee in the ensuing months brought some relief to black voters, it wasn’t until passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that the voting rights of blacks in Fayette and neighboring Haywood County were enforced.

By the 1950s, black athletes were being accepted in all professional sports—including baseball, basketball, and football. They were employed so rapidly after the field was opened that their induction into formerly all-white teams was no longer of special news value to the minority press. ANP’S clients were particularly interested in boxing, which had many nationally known personalities. Although the fame of the mighty Joe Louis was beginning to decline, Joe Wolcott was in his heyday. I had the opportunity to see these great heavyweights in action as well as to interview them on various occasions.

I ran into a wall, however, when I attempted to crash what had previously been considered by sportswriters to be an exclusively male domain. I was barred from the front row seats reserved for reporters. The D.C. Boxing Commission informed me that it was against the rules for women to sit at ringside. With that, I began waging a battle for equal rights for women sportswriters that lasted several months.

After breaking through the sports world’s gender barriers one by one, Dunnigan had no trouble interviewing such superstars as Boxing Hall of Famer Jack Dempsey, World Heavyweight Champion from 1919 to 1926. (From Dunnigan, Black Woman's Experience)

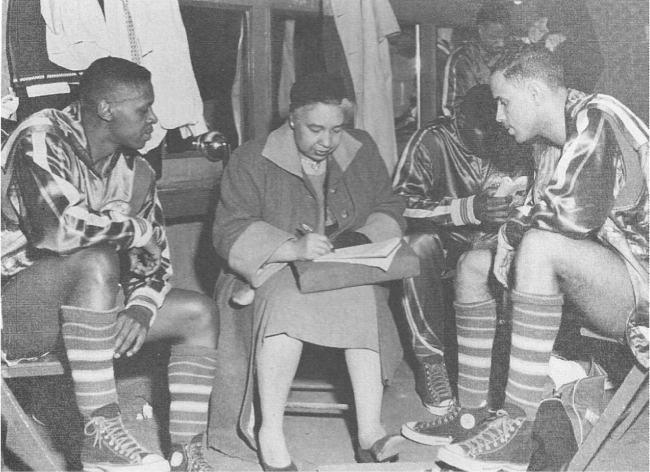

With Harlem Globetrotters (From Dunnigan, Black Woman’s Experience)

I had several Negro sportswriters in my corner. Foremost among them were Fred Leigh and Art Carter of the Afro-American and Chick Webb and Ric Roberts of the Pittsburgh Courier. Leading the fight on my behalf was Michael (Casey) Jones, a prominent boxing promoter. Jones thought of a scheme that he thought would do the trick. He formed an organization known as the Negro Boxing Writers Association and became its first president. Roberts was named executive vice president and Webb correspondence secretary. Carter was elected chairman of the executive committee, and Leigh was appointed historian. Other officers included Sam Lacey, treasurer; Van Nixon, secretary; and me, librarian.

The organization sent a delegation to the Boxing Commission demanding that I, a sportswriter and an officer of the Negro Boxing Writers Association, be allowed to cover fights from ringside like all other sportswriters. The scheme worked, and I became Washington’s first and only woman sportswriter.10

As a representative of the Negro Boxing Writers Association, Casey Jones was invited to appear before the District Boxing Commission in 1949 to verify a statement he had earlier made before a congressional hearing regarding the appointment of a Negro to the Boxing Commission. Pointing out that the majority of fighters were Negroes and 85 percent of the fans were Negroes, Jones said his association would lead a boycott against the fights unless his request was given some consideration.

“Negro newspapers represent the articulate voice of the Negro people,” declared Jones. “And they are advocating the infiltration of Negroes all down the line from Commissioners to referees and inspectors. Unless they get some favorable action, Negro fans will boycott the fights.”

Through continuing conferences and negotiations with boxing officials, Jones and his association finally succeeded in having Dr. Joe Trigg, medical advisor for the commission, elevated to boxing commissioner. Continuing his fight for more Negro participation, Jones finally succeeded in getting Sam Barnes, instructor of athletics at Howard University, and Fred Leigh, former Afro-American sportswriter, appointed judges.

When I moved into football coverage, I was welcomed by local sportswriters who had become accustomed to seeing me around and had learned to respect my work.

Fellow Kentuckian “Happy” Chandler, a former senator and the state’s forty-fourth and forty-ninth governor, was commissioner of baseball from 1945 to 1951. His approval of Jackie Robinson’s contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers opened the major league to black players. (Dunnigan Papers, MARBL, Emory University)

Baseball was my next venture, although there was no client interest in Washington’s American League team since, like all the others in the league, it had no Negro players. Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier in the National League when he was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, and although I never got to see him play, I covered him on many visits to Washington, including several for civil rights causes.

One time, I attempted to cover a Major League Baseball game from the press box at Washington’s Griffith Stadium but was denied entrance.11 I was very upset because I thought I was being barred because of race. I let a male reporter use my press pass just to see what would happen. Although the pass bore my name, the reporter was admitted to the press box without question. Then I realized that the discrimination was not based on race but sex.

I still attempted to cover games in the Negro league, even if I had to do it from the bleachers. Once I tried to get an interview with Satchel Paige when he played in Washington with the Philadelphia Stars against the Homestead Grays. Not being able to talk with him either in the press box or the locker room, I sauntered down to the dugout before the game. The superstitious players were furious, contending that a woman in the dugout would bring bad luck. The irate pitcher tried to control his anger and answer my questions with civility if not courtesy. He closed the interview with the curt remark, “I know we’re going to lose this game. A woman sashaying around the dugout will surely put the jinx on us.”

“The famous Satchel Paige will never lose a game,” I replied cheerfully.

Paige was the starting pitcher but was relieved after three innings. And sure enough, to my regret, his team did lose the game. The manager of the Philadelphia Stars sadly lamented that this was the first game they had lost since Satchel had been on the team.