21

EISENHOWER’S PIQUE

During my regular news coverage, I seldom missed a press conference held by top government officials, and I never missed an opportunity to raise questions regarding problems within their respective agencies of concern to black people. Inevitably, I became sort of a “flea in the collar” of many of these officials.

My routine questions regarding segregation in swimming pools and on playgrounds in Washington, D.C., were welcomed by Truman’s interior secretary, Oscar Chapman, who favored the abolition of discrimination, but the problem continued many years before it was finally resolved.

There were marches on the D.C. Recreation Department, sidewalk polls, countless letters of protest, and unpublicized negotiations and conferences before the Washington Recreation Board in 1949 announced a policy for gradual desegregation. The Interior Department, however, declared that all of its land should be operated on an integrated basis and opened its swimming pools under the oversight of park police specially trained to see that the integration order was carried out quickly and with the least possible trouble. The D.C. Recreation Board finally abandoned its plan to desegregate playgrounds one by one over an unspecified period of time when the Supreme Court announced its school desegregation decision in 1954.

Another issue constantly raised by the black press was the need for clarification of government policy on the operation of federally supported health centers. When Surgeon General Thomas Parran Jr. told a press conference in 1947 that more young women were needed in the nursing profession, I asked about opportunities for Negro nurses. He quickly replied that this was left up to local authorities. He explained that while federal law required each state receiving federal funds for hospitals to make all facilities available to all people of the state, this dealt only with physical facilities, and the federal government had no jurisdiction over the employment of personnel.

The policy of allowing the states to decide how federally supported hospitals were operated with regard to racial segregation was reiterated in 1948 by Parran’s successor as surgeon general, Dr. Leonard Scheele, who demurred in response to my question on the issue that he was not familiar enough with the text of a hospital construction bill pending before Congress “to express an opinion on the segregation policy to be practiced at prospective medical facilities” but that he assumed it would be left to the states. The black press, as before, blasted this position because African Americans were consistently denied a fair share of jobs and other federal benefits in most instances where funds were administered by state or local officials.

Finally, in July 1948, reporters heard a different response from Federal Security Administrator Oscar R. Ewing, who replied immediately and unequivocally that a proposed thirteen-story clinical research center in Bethesda, Maryland (the future National Institutes of Health) would hire the two thousand employees—professional and general—needed to staff the center on an interracial basis and would admit patients without regard to race. A few months later, Ewing recommended to President Truman that the government adopt a definite policy guaranteeing the availability of adequate medical services for all, regardless of race, stating, “We can no longer tolerate in our society a system of medical care under which Negro physicians and Negro patients are discriminated against.”

Because federal law made no stipulation concerning discriminatory practices that barred members of minority groups from serving on the staff of hospitals, the FSA recommended that “all maintenance subsidies to hospitals be assured only on condition that professional personnel should be accepted as staff members, or as other workers, in the underwritten hospitals without discrimination as to race, religion, or sex.”

In October 1948, one month after Ewing’s recommendations to the president, Gallinger Hospital opened its doors to interns and medical training students of Howard University.1 Prior to this time, Freedmen’s Hospital2 was the only place in Washington for training of interns from Howard’s Medical School. Under the new arrangement, Howard was allotted a yearly quota of one-fourth of the total number of interns admitted, while the city’s two white medical schools—Georgetown and George Washington—each was allotted a quarter of the slots, with the balance reserved for interns recommended by the District Health Department. Even then, however, the policy of segregation of physicians and nurses on the hospital staff remained status quo. I raised the issue in an early press conference of Oveta Culp Hobby soon after she took office as secretary of health, education, and welfare (HEW). She appeared a bit stunned by the question and passed it on to one of her associates, who gave a long, rambling but indefinite answer. Nevertheless the exchange served as the basis for a good news story and set wheels in motion that eventually brought results, although complete integration in medical institutions was not accomplished until passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which (in Title VI) barred discrimination in programs supported by federal funds.

The integration of public schools, barely in its early stages during Eisenhower’s first administration, was having the ironic effect of eliminating jobs for Negro teachers as they were replaced with whites. Therefore, when U.S. Commissioner of Education Samuel M. Brownell told a news conference that there were not enough teachers available to fill existing job vacancies, I called to his attention the fact that there was a surplus of Negro teachers in the country, many of whom were then unemployed.

“If the school systems throughout the country would employ teachers on the basis of qualifications rather than race, this problem could easily be solved, could it not?” I asked.

His face flushed and he gave no answer except to say something like, “I suppose so.”

Commissioner Brownell was put on the grill again in early 1955, when he appeared before the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, along with HEW Secretary Hobby. Mrs. Hobby was appearing on behalf of President Eisenhower’s aid to education bill aimed at relieving classroom shortages. The bill seemed to represent an apparent shift in previous administration reluctance to aid education. During the five- or six-hour grilling, Commissioner Brownell offered that by authorizing the purchase of bonds issued by state school building agencies, matched by federal grants, the bill would give the states “self-determination” rather than federal interference in how they operated. Throughout the hearing, the question of supplying federal funds to aid segregated school districts kept coming up with no clear answers, although Mrs. Hobby did deny the charge that this plan was devised as a way of avoiding the Supreme Court’s desegregation order. My reports as well as those in the black press in general described the legislation as an attempt to circumvent the Supreme Court ruling by placing policy-making power in the hands of the states. At the close of the first day of Senate hearings, George Meany, president of the American Federation of Labor, put his union on record as supporting an amendment to the school aid legislation to deny federal aid to states that abolished their public school system in an attempt to nullify the Supreme Court decision.

It was common knowledge around Washington that Jane Spaulding, one of Eisenhower’s top black appointees as HEW assistant secretary, lost her job after less than a year because she opposed Secretary Hobby’s position on school desegregation. She took her case to the NAACP, and after much adverse publicity in the Negro press and a threatened investigation by the civil rights organization, the administration gave her an office at the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, which she retained until public sentiment died down.

The greatest advantage of black reporters being accredited to the White House was the opportunity to raise questions of interest to the black population in order to get a face-to-face reply on important issues and the president’s personal opinion on various subjects, as well as a promise as to what he intended to do about existing problems. This theory worked very well under the Truman administration. Whenever a question was raised with him, the reporter would either get a direct, concise answer or a curt “no comment.” Either way, the reporter would have a story. But this theory didn’t work so well with President Eisenhower.

It appeared that Mr. Eisenhower was not familiar with many questions raised on civil rights issues. Either he was not concerned enough to alert himself on these controversial matters or his advisors didn’t bother to brief him sufficiently on this all-important subject. In any case, he would become very annoyed whenever such questions were raised.

The president was not in favor of any legislation aimed at wiping segregation from American society. As this question continued to arise at press conferences, the president once replied to the effect that it was his prerogative not to talk about segregation or discrimination. He said it was his job to support any federal court order that had been properly issued under the Constitution and to intervene where compliance was prevented by unlawful action. He had to do that, he said, but it was an entirely different matter for him to instigate new methods or new laws relating to this problem, which he contended could not be solved except by understanding and reason.

In spite of his acknowledged opposition to new legislation prohibiting segregation and discrimination, the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) in 1954 presented President Eisenhower with the coveted Russwurm Award, the highest honor offered by the nation’s Negro publishers. The annual award is presented in honor of John B. Russwurm, founder of the Negro press in America, for outstanding contributions to human relations and racial understanding. According to the publishers, they gave the award in recognition of the president’s order to eliminate separate schools on army posts, for strengthening the (Truman) policy of integration in the armed forces, and for the abolition of segregation in public facilities of the District of Columbia (as required by the Supreme Court) during his administration.3

Ethel Payne came to Washington in late 1953 as a reporter for the daily and weekly Chicago Defender, and because she represented one of the two Negro daily newspapers in the country (the other being the Atlanta Daily World), she qualified for immediate membership in the Capitol Press Galleries and the White House press corps. As I did, she raised direct and pointed questions at presidential press conferences.4 On one occasion, she asked the president a question regarding discrimination in housing. Mr. Eisenhower became furious, either because he did not know the answer or did not wish to commit himself on the subject.

A few weeks later at his April 29, 1954, conference, I posed a question on discrimination in the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. This was a question that had been on the minds of many people for a long time. I had continuously followed this fight led by the federal workers’ union and was concerned about the climax. In order to bring the president up to date on the problem, I explained that the bureau had been charged with defying the recommendation of the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) by refusing to employ Negroes as apprentice plate printers. The FEPC had agreed six months earlier that the applicants for the apprentice plate printers jobs at the bureau were victims of racial discrimination. These findings reportedly had been made known to the U.S. Civil Service Commission but had never been released publicly. With this explanation, I asked Mr. Eisenhower if he planned to take any steps to have the FEPC’S recommendations and decisions made public and to force the Bureau of Engraving to fulfill its obligations under the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act.

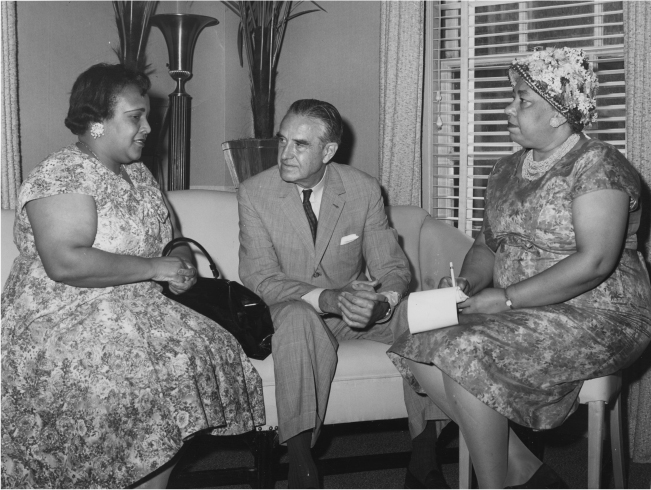

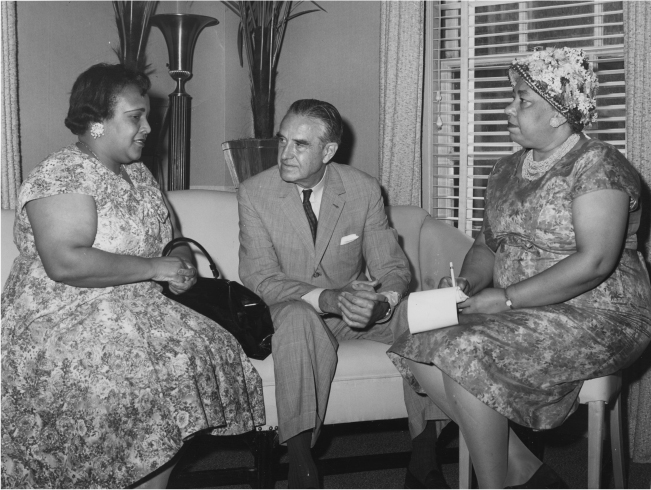

Ethel Payne, who began reporting from Washington, D.C., for the Chicago Defender in 1954, often covered stories with Dunnigan, her friend and mentor. They jointly interviewed W. Averell Harriman, who held many high posts in Democratic administrations, including ambassador, peace negotiator, and cabinet secretary, and who was governor of New York from 1954 to 1958. (Photo by Sorrell; Dunnigan Papers, MARBL, Emory University)

President Eisenhower was infuriated. He asked why I had not gone to the proper departments of government to ask this question and specifically whether I had raised the matter with the Bureau of Engraving or the Civil Service Commission. He added that he liked to come to these press conferences completely prepared to answer as well as he could any questions that came up. But he couldn’t be expected to know details on how a particular thing could be handled. Then, a bit calmer, he added that he didn’t know too much about this but he would have Mr. Hagerty (his press secretary) look up this particular question and give an answer in time.5

Another time, Ethel asked the president if the administration was lending its support to proposed legislation to bar segregation in interstate travel. In clipped words, the president replied that he did not know by what right the reporter should say that legislation would have to have administration support. He added that the administration was not trying to support any particular or special group of any kind but was trying to do what it believed to be decent and just.6

On one bright morning in midsummer of 1959, the president cheerfully faced the regular press corps with perhaps no thought of being badgered with a race question, since no burning civil rights issues were in the news at that moment. That is probably why he seemed so startled when a reporter hit him right between the eyes with a direct question as to whether he felt that “racial segregation is morally wrong.”7

“Myself?” asked the president, appearing a bit stunned.

“Yes, sir,” replied the reporter.

After some hesitation, Mr. Eisenhower managed to say that there are several phases of segregation but he assumed the reporter meant that phase which deprived citizens of their economic and political rights. He thought that phase was “morally wrong.” The reporter pursued the question no further and the president, probably thinking he had handled it well, went on with the conference, recognizing another reporter with a different line of questioning. He was probably surprised (if he saw it) when the reporter wrote, “President Eisenhower admitted that political and economic segregation is wrong, but he tactfully avoided any comment on social or educational equality.”

In an obvious attempt to intimidate Ethel and me, Louis Lautier, a staunch Republican, ardent conservative, and absolute male chauvinist, took a crack at us in his syndicated column. (Although we had no proof of his motive, we felt confident that it was instigated by the White House.) He wrote a critical analysis of the questions we raised, saying, among other things, “The two gal reporters are hell bent on competing with each other to see which one can ask President Eisenhower the longest questions.”

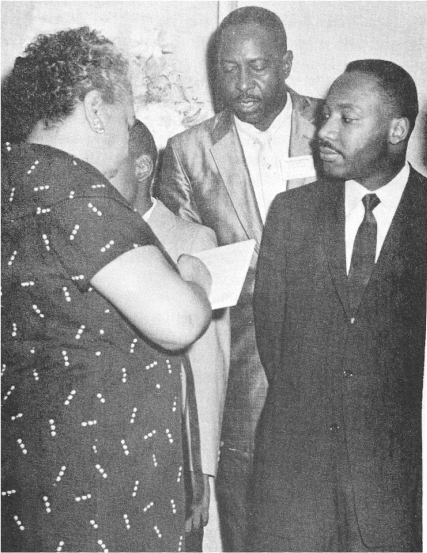

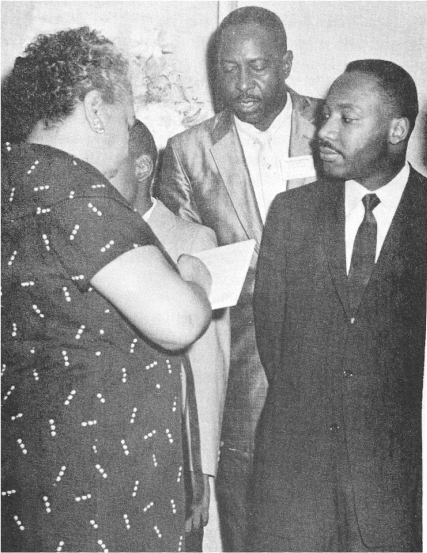

Dunnigan interviewed National Bar Association president (and future D.C. superior court judge) William S. “Turk” Thompson and keynote speaker Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. at the NBA’s 1959 convention. King had repeatedly asked President Eisenhower to call segregation “morally wrong,” and the president finally did a few days after the civil rights leader called his failure to do so “tragic.” (Photo by Stitt; from Dunnigan, Black Woman's Experience)

Lautier’s criticism brought immediate protest from Clarence Mitchell Jr., then chief of the NAACP Washington Bureau. In a letter to the editor of the Afro-American dated May 25, 1954, Mitchell expressed great concern about this attack.

“The NAACP has had deep interest in both of the questions raised by these reporters,” Mitchell wrote. “We were delighted when the queries were put to the President at his press conferences.” He noted that Ethel’s question regarded top officials at the Housing Agency having done nothing to implement a promise made by Eisenhower four months earlier that certain corrective steps would be taken in the field of government-assisted housing programs. Since the president had made the promise, Mitchell opined, he should be asked to explain the delay.

Regarding my question about discrimination in the Bureau of Printing and Engraving, Mitchell described the situation as “a conflict between top officials which the President must settle.” In closing, he expressed the hope that we would continue asking questions because, “after all, that is what a press conference is for.”

Using Lautier’s phraseology, I might say the White House seemed “hell-bent” on gagging me, as far as questions on civil rights were concerned. This became evident at an embassy party, where I was approached by Max Rabb, the president’s special advisor on minority affairs. Over cocktails, in a very pleasant manner, he made a proposition that went something like this:

“Alice, you’re always asking the boss questions on some subject with which he is not familiar. This is very embarrassing to him. Why don’t you check out your questions with me before going to the conferences? Then I will brief him on the situation and he will have a ready answer. All you want is an answer anyway, isn’t it? This way you’ll be sure to get your answer.”

This sounded all right at the moment, and I agreed, but when I gave it more thought, I was enraged because out of the five hundred or more reporters, I was the only one, to my knowledge, who was asked to check her questions with the White House beforehand. But since I had already agreed, I felt I had to go along with it.

Before the next press conference, I called Rabb to tell him I intended to ask the president a question about the FEPC bill pending before Congress.

“Oh, no, no!” he exclaimed. “Don’t ask that question.” Then he went on to explain something about “the boss” working on this measure, and if it were brought to public attention, the southerners on the Hill would take reverse action and throw a roadblock in the president’s plans.

This was exactly what I was afraid would happen. I was hurt as well as mad. I sat through the conference “all stuffed up,” watching the white reporters jumping up all around me and asking questions of interest to their readers, none of which provided anything of interest to our publications. It seemed to me that it would have been a breach of journalistic ethics to ask my question despite Rabb’s advising against it. So I left the press conference with nothing of special interest to our readers. I might as well not have been there.

I vowed to myself that I would never do it again—never check my questions in advance with anybody on the White House staff—but instead get up like everybody else and ask whatever I pleased.

But it didn’t happen that way. Mr. Eisenhower had a different idea. He apparently had made up his mind never to recognize me again—and he didn’t! I would go to every press conference and jump to my feet between every question, shouting for attention like all the other reporters, “Mr. President! Mr. President!” But Mr. President ignored me. He would recognize people all around me, in front of me, in back of me, on either side, but he always left me standing like the invisible man. The white reporters began to notice the snub, and one day one of them asked, “Do you realize how many times you were on your feet today asking for recognition?” When I replied that I hadn’t counted, he replied, “Fifteen times.”

Another white reporter wrote a story for a chain of newspapers in his state on the Eisenhower snub of a Negro reporter, and Drew Pearson, the nationally syndicated columnist, made note of it in his column. The Afro-American also picked up the story, and a New York radio station called me for a telephone interview. The New York Post called it an attempt by the president to dodge an issue as well as to pigeonhole two women reporters. Labor’s Daily, May 21, 1957, ran a long article on the controversy, stating that I had not been recognized by the president in more than a year and a half, while Ethel Payne had been ignored as well.8

In a column in the Daily Worker headed “The Presidential Gag on Civil Rights,” Abner W. Berry called the president’s snub “censorship” and “an insult to the representatives of the Negro press,” noting that it came “as these [reporters] became more persistent in seeking the President’s thoughts on the role of the Executive in enforcing” civil rights decisions. Until the snub, Abner added, “newspaper readers at least got the fumblingly illiterate Eisenhower reactions to the issue of civil rights.”9

The popular black weekly Jet magazine’s “Ticker Tape” column observed, “Alice, the most regular attendant [at the press conferences] of the D.C. Sepia correspondents, hasn’t gotten a word in edgewise in over a year and is trying to make a racial issue of the matter.”10

Actually, I was not trying to imply that this issue was based on either race or sex discrimination, as it seemed more likely a move on the part of the president and his advisors to dodge controversial questions on which he was either unable or unwilling to take a definite stand.

When the 112 ANP newspapers picked up the story, it became widespread around the nation. But the story did not meet the approval of ANP Director Claude Barnett. He chided me for all the adverse publicity the president had been receiving regarding my questions and instructed me in a letter that I shouldn’t “lean too hard on the president.” I had no assurance, he wrote, that Eisenhower’s motive was racial, and it could be personal. Barnett’s letter concluded that the president might have been informed that I leaned toward the Democratic Party, and his action might be due to my partisanship, which the ANP did not condone.11

President Kennedy recognized the importance of the black press when he called on Alice Dunnigan at the first live, televised presidential press conference on January 25, 1961, departing from Eisenhower’s practice of ducking civil rights issues. The White House also assigned a regular seat at the news conferences to a reporter for black publications, Jet and Ebony magazines’ Simeon Booker (second row, second from left, in bowtie). (Abbie Rowe, White House/John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

One White House staffer suggested that the controversy had something to do with professional jealousy on the part of male columnists and called it an “unprecedented professional battle-of-the-sexes.”

There was so much notoriety around the situation that presidential assistant Rabb took to the air to deny that he had requested of certain reporters that questions to be raised at the press conference be submitted in advance for White House approval. In an interview with Tomlinson D. Todd, director of the Americans-All radio program on Washington’s WOOK, Rabb maintained that all questions raised at these conferences were spontaneous and that the president never knew in advance what he was going to be asked.12

After all this publicity on the Eisenhower controversy, when I was recognized by President John F. Kennedy at his first press conference in 1961, the newspapers did stories to the effect that after several years of operating under a gag rule, Alice Dunnigan’s silence at last has been broken.

A Jet headline read, “Kennedy In, Negro Reporter Gets First Answer in Two Years.” The article led with the observation that at “his first nationally televised press conference in Washington, President John F. Kennedy quietly scrapped a long standing White House policy,” which was “to ignore veteran correspondent Alice Dunnigan at press conferences.”

For two years, grandmother Dunnigan bobbed up and down at press conferences to get the eye of ex-President Eisenhower. She was skipped, passed over, and ignored. Even reporters noticed the snubbing and jokingly told her “to save her strength.” She was regarded as an agitator by conservative newsmen.

… The ex-teacher and native of Russellville, Ky., got in Ike’s hair twice on civil rights matters—revitalizing the Contract Compliance Committee and ending segregation at schools on military bases. Following Mrs. Dunnigan’s pinpointing of the conditions, the administration took action—in each case. Recalled Mrs. Dunnigan: “Colleagues told me that I got more action than anyone. Just ask the question.”13

After this news conference, letters and telegrams came from people around the country who had seen it on television. Some complimented me for being the first black reporter to ask President Kennedy a question. Members of the Women’s National Press Club lauded me for being the first female reporter to do so.

Thus, the controversy with presidents had ended for me, and I continued my normal routine of covering the White House press conferences.