Introduction to Qigong:

Harnessing the Energy of Life

Defining Qigong

The word “Qigong” is made from two syllables that are discrete words. Qi means vital life energy or life force, often translated just as “energy.” Gong means cultivation, practice, or work. Implicit in the word “Gong” are the concepts of effort, time, and purpose. So, while the simplest translation is “energy work” or “energy cultivation,” a fuller definition is “effort over time put into the cultivation of life force, for the purpose of being able to sense it, increase it, and direct its use.” Those uses can vary considerably, depending on each individual’s goals.

If we look at the five philosophical bases of Qigong, we can get a general understanding of possible purposes or uses.

1. Daoist Qigongs are most concerned with aligning with the natural world, primarily for better health and longer life.

2. Buddhist Qigongs are most concerned with spiritual cultivation according to Buddhist principles.

3. Medical Qigongs are most concerned with healing illness and preserving health.

4. Martial Qigongs are most concerned with facilitating martial ability and healing related injuries.

5. Confucian Qigongs are most concerned with intellectual development, primarily in service to the culture, community, and government.

There is substantial overlap among these philosophies and their consequent practices. Although all the Qigongs taught here are medical, some have their roots in Daoist and Buddhist practices as well. There is no religious content or overtones to be found here. These are entirely secular medical practices.

The Three Regulations

In order for any practice to truly be a Qigong, it must adhere to the principle of the Three Regulations: the regulation of the body, whether in a moving or stationary practice; the regulation of the breath; and the regulation of the mind, which includes thinking and understanding but is more about the most subtle ways of perceiving Qi and related aspects of one’s being. When all three are combined, you have the most effective means of regulating the Qi.

Other types of exercise may have two of the three, but Qigong must have all three. Energy moves differently once you begin to modify your breath, thoughts, and movements. When combined conscientiously, they produce many different effects.

The Basic Standing Posture: The Side Channel Stance

In many Qigong practices and in many styles of Taiji, the student is often given this instruction, or a very similar variation, in order to get into the proper standing posture: “Stand straight, with your feet parallel at shoulder to hip width apart, your knees slightly bent, and weight evenly distributed across the bottoms of your feet.” This gets you into the general ballpark of what is known as the Side Channel Stance, also known as Zhan Zhuang, but in practice most students stand with their feet too wide with this instruction. This is because, in addition to possibly not having sufficient body awareness, they are not told exactly what is meant by “shoulder” and “hip” and how those body parts relate to the side channels.

The left and right side channels run through both legs, the torso, both arms, and the head. All of the twelve regular meridians and half of the extraordinary meridians grew out of the core side channels meridians, and the side channels continue to influence Qi flow through all of those meridians.

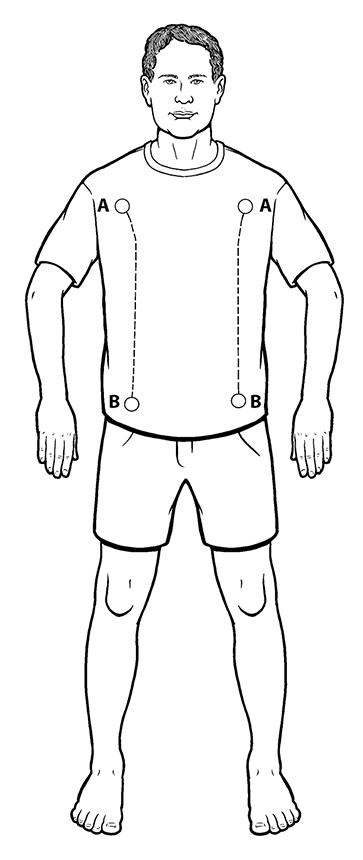

Within the torso, the upper portion is delimited by the shoulder’s nest and the lower portion by the Kwa, which is roughly the center of the inguinal groove (points A and B on Figure 16.1, respectively) If you draw your shoulders forward, toward the center of your chest, you’ll feel a hollow form just to the chest side of your shoulders. That depression indicates the front portion of the shoulder’s nest and is the only landmark you’ll need to identify its location. That location is what is meant by “shoulder” in the instruction, considerably narrower than the outer tip of the shoulders that most beginners assume.

To locate the Kwa, squat slightly, as though you are about to sit on a stool. Try to not let your knees move forward as you do this, although slight knee movement is fine. In the center of your inguinal fold, where your legs join your torso, you’ll feel a depression form that is similar to what you felt at the shoulder’s nest. That depression indicates the lower front portion of the Kwa, which is all you need to identify its location. The Kwa is really what is meant by “hip” in the stance instruction.

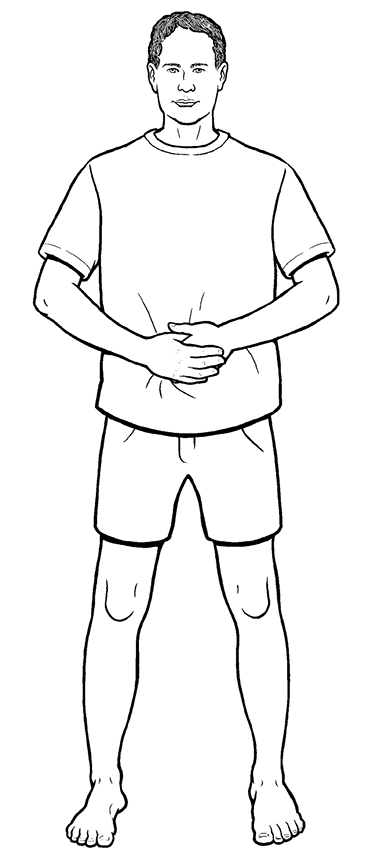

Figure 16.2 (Side Channel Stance)

By standing with your feet parallel and on the side channels, you are automatically minimizing physical obstruction in those channels and maximizing the potential to move Qi effectively through them. That’s important in this practice and in most styles of Qigong. If your shoulders are wider than your hips, place your feet at shoulder width; if your hips are wider, place your feet at hip width, to give you the most stable stance. Allow your arms to hang comfortably at your sides (Figure 16.2). Practice this by itself until you get the clear feeling you can get into a Side Channel Stance without having to check yourself. You’ve now learned the Side Channel Stance.

General Breathing Guidelines

If you are already trained in Daoist natural breathing, you should use that in this practice. Otherwise, simply keep your breath comfortably long and full. Breathe in and out through your nose only (unless your sinuses are too congested to allow that), and try to breathe into your belly more than into your chest. The most important thing is to keep your breathing relaxed. It should never feel forced or strained. That would increase tension in your nervous system, which is counterproductive in these practices and bad for your health in general.

Before adding the breathing component to any practice, it’s a good idea to check your breathing alone first. Get in your Side Channel Stance, arms relaxed at your sides, and breathe comfortably in and out through your nose. See if you can get your belly to expand a bit on each inhalation and retract back to its starting point on each exhalation. Try to keep your chest relaxed, with a sense of sinking, so that it doesn’t move or moves very little with each breath. Let your breathing become slower and fuller, maintaining a sense of relaxed comfort. Once you’ve found your longest comfortable breath, note how that feels and approximately how long it takes.

In each Qigong practice your breath will link to your movement in slightly different ways. Sometimes one breathing cycle will match the entire movement, and sometimes it will only include part of a movement. In either case, the length of your comfortable breath will determine the speed of your movement. You can always adjust the speed of your movement to match your breath, but you never want to force your breath to match the speed of a movement that you may set arbitrarily. Once you are clear about that, you can add the breathing to the practice.

In all cases, keep your breathing circular. That is, continue to inhale all the way through to the time to exhale, and then continue to exhale all the way through to the time to inhale. There should be no held breath at any time in these practices, no gaps between inhalation and exhalation.

Working with Your Qi

Learning to work with your Qi can be the most difficult yet the most rewarding part of your practice. You are learning to sense and influence the subtlest parts of yourself, things of which most people remain completely unaware and so never attend to. While you will learn to feel your Qi kinesthetically, it’s the focus of a quiet mind that allows the kinesthetic sense to develop. This is the first big difficulty. So much of contemporary life seems designed to distract and overstimulate the mind, so, especially in the earlier stages of your practice, it’s important to find a peaceful environment free of all distraction to help you quiet your mind and feel for various Qi sensations.

Some people feel Qi fairly soon in their practice, but most take longer to develop that sensitivity. Don’t try to rush things; allow yourself to grow at your own pace. If you are one of those who take longer, the second big difficulty is not succumbing to frustration, disappointment, or a sense of hopelessness or failure. Remember that gong (practice) contains the meaning “effort over time.” For those wanting more guidance in cultivating Qi sensitivity, my first book, Chinese Healing Exercises, contains an exercise called Waking the Qi: Dragon Playing with a Pearl that will help you quickly develop a sense of Qi between your hands, a very useful first step in any Qigong practice.

Along the same lines, remember that learning how to do Qigong is not the same thing as doing Qigong. Consider that if you want to play a musical instrument, you wouldn’t expect to pick it up one day and master it the next. Even if your goal were simply to entertain yourself or a few friends and family at home, you’d expect to practice for months at least, learning what you need in order to do that. If you have greater ambitions, you’d expect to invest more practice time and effort in order to meet your goals. It’s exactly the same with Qigong. The more you practice, the better you’ll get, and when you are actually doing Qigong, you have the greatest potential for continued improvement.

If you are less sensitive to Qi sensations, it may be encouraging to know that long before you feel Qi, you will still positively influence it and even feel its effects if you know what to look for, just by carefully practicing the Three Regulations. Here’s why:

1. Our bodies are “wired” with nerves and meridians, both of which conduct subtle energies. The movements of Qigong in part are intended to move your body in specific ways, through the earth’s electromagnetic and gravity fields. Moving conductive wiring through energy fields generates a current. The sum of all bioelectrical energies is Qi. Regulating the body helps generate those healing bioelectric energies and amplifies Qi.

2. If you are able to get breath into your belly with minimal movement of your chest, you’ll be drawing in more atmospheric Qi (Qingqi). That imbues your blood with more Qi, and as belly breathing massages your internal organs, more Qi-infused blood is delivered there, increasing organ health and functionality.

3. The mind directs the Qi. If you keep your mind focused on those parts of the practice included in the instructions, your Qi will be directed there by your mental focus, even if you don’t feel it.

4. After practicing for a few weeks, you may notice that your mood is better, you’re sleeping better, you have more energy throughout the day, and you don’t get sick as often as you did. If you do get sick, you may notice that your symptoms are milder and don’t last very long. These are all signs that your practice is having a positive effect, regardless of whether you feel Qi.

Practice Times

Generally, practicing Qigong between 5 a.m. and 7 a.m. is considered ideal. The air is often the cleanest it will be throughout the day, and the Yang Qi is strong and still growing. When you are practicing an organ-specific Qigong (as all of these are) for the purpose of healing a medical problem or for optimizing organ function to maximize health and increase longevity, practicing at the organ’s ascendant time of day will provide the very best results. Those times are given at the end of each Qigong instruction. With contemporary time constraints this may be impossible, but it’s important to know those constraints are not the schedule of nature. When trying to heal a significant illness or to cultivate longevity, follow nature’s schedule as much as you can for greatest benefit.

If you are unable to practice between 5 a.m. and 7 a.m. or at the organ’s ascendant time, you can practice anytime you can fit it into your day. Any practice is better than none, and you’ll get substantial benefits regardless.

Length of Practice

Some Qigongs are composed of a single movement or stationary posture. Most practices taught here have been extracted from longer medical Qigong sets. Some of those sets have specific medical goals—Dragon and Tiger Qigong is used extensively in China as a cancer treatment protocol, for example—while others are intended to benefit health in general ways, still giving each Organ System its necessary attention. Whether a single-movement Qigong or a full set, each practice takes approximately twenty minutes to perform, which is often all that’s required to maintain health if you are in good health. When trying to heal a particular illness, it’s recommended to perform the entire practice two or more times a day to more rapidly and effectively build up a body’s healing energies and reserves.

Here, we are not performing Qigong sets. Rather we’re using a single Qigong exercise to address a specific condition and combining it with acupressure and herbs in order to provide an integrated approach to holistic healing, as it is usually practiced in China.

For a single Qigong, twenty minutes of daily practice is a reasonable goal to work toward and is the minimum required to maintain good health. If you are working to heal a medical problem, longer is better, but never practice to exhaustion. You can practice a number of times a day if you can’t do more than twenty minutes at a time. Don’t be discouraged if you can’t manage twenty minutes. Practice as long as you comfortably can, and as your health improves, you’ll gradually become able to add more time.

You may include more than one Qigong practice from this book in your daily routine, but do not try to link them into a set. They were not designed to be used that way. Ideally, practice each Qigong during its ascendant time of day. Alternatively, practicing different Qigongs at different times of day also works fine. If including more than one Qigong in a single practice session, be sure to fully conclude the first before beginning the next one. Doing a Qi storage after each Qigong is a good way to ensure that separation.

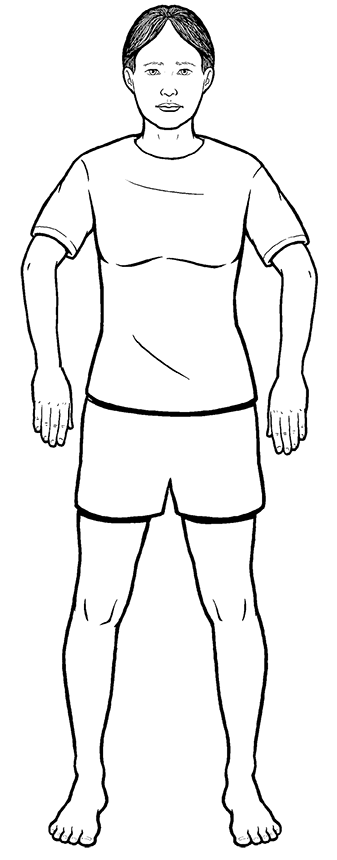

Ending a Practice Session: Storing Qi in the Dantian

At the end of each practice session, you want to store the Qi you’ve just acquired so that you build up your reserves rather than allow it to dissipate. The easiest way to do this is by bringing your hands to your Dantian. Men should place their left hand directly on their Dantian and then place their right hand over their left (Figure 16.3). Women should place their right hand directly on their Dantian and place their left hand over their right. You may want to close your eyes, although that’s not a requirement. Feel the warmth of your hands and any sense of Qi you have penetrate into your Dantian. Place your mental focus on your Dantian, and gather the Qi you feel throughout your body there. This should not require any force or effort. With your mind being present at your Dantian, Qi will be drawn there and absorbed in much the same way as water is absorbed by a sponge. Allow any sense of activity to become quiet and still, as your mind becomes quiet and still.

You can stay in this posture as long as you’d like. When everything becomes quiet and it feels as though you’ve absorbed whatever Qi you can, you’ve completed Qi storage at the Dantian. Then simply lower your hands, open your eyes, and do whatever comes next in your day.

Final Practice Guidelines

Do not practice when you are very hungry or very tired. Your Qi body is not well consolidated during those times, and it will be difficult for you to move, acquire, or store Qi. Have a light snack if you are hungry, take a nap if you are tired, and then practice.

Do not practice when you are very full. Much of your body’s energy is being taken up by the process of digestion, and there may be additional discomfort if you have eaten too much.

Do not practice when you are very emotional. Your Qi will be scattered or otherwise directed away from its normal course and therefore much more difficult to access and control. If you are upset, it is beneficial either to stand in the basic standing posture, breathe as instructed, and wait for your emotions to calm or to follow the exercise prescription for emotional distress on page 271 of Chinese Healing Exercises.

Do not practice in a toxic environment. This can be something as obvious as a room that has been freshly painted or recently smoked in or as subtle as a place just not feeling right to you, even if you can’t figure out exactly how or why that is. Toxic environments also include hospitals, where there is a lot of sick Qi, and cemeteries, which may seem peaceful but are considered by the Chinese to be full of dead Qi. When you practice Qigong, you are interfacing with the energy of your immediate environment and are particularly susceptible to whatever energies may be present.

Do practice in the healthiest environments you can find. Traditionally, the Chinese prefer places on mountaintops, by the ocean, or in forests. Clean outdoor environments provide the most abundant source of healthy Qi, which will be most supportive of your goals.

Do not practice within one to two hours of sexual activity. When practicing before sex, much of the Qi you may acquire will be lost during sex. When practicing after sex, you will not be able to store any Qi you’ve acquired until after your Qi body is once again stable and consolidated. Neither instance is dangerous; it’s just a waste of your practice time. This is most relevant to men, but some women may experience similar effects.

Women should be careful during menstruation. For some women this is not a problem, but Qigong does move Qi, and Qi moves blood. If you notice that your bleeding becomes heavier or prolonged, do not practice during menstruation.