Second Concept:

Meridians, the Pathways of Health

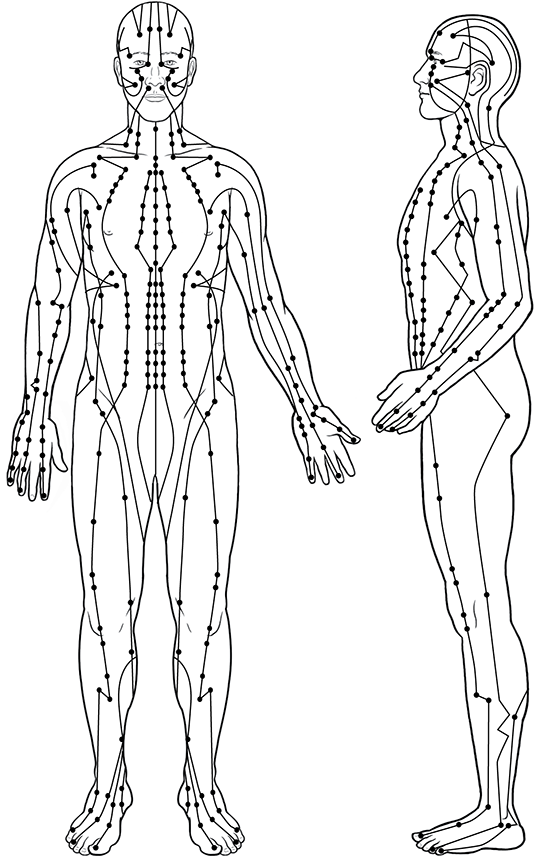

The second foundational concept to understand is that of meridians, the nonphysical vessels through which Qi flows within the body (see Appendix 2, Note 1.2).

There are twelve regular meridians, divided into six bilateral Hand and six bilateral Foot meridians. Each meridian has its own set of acupoints that may be needled for specific therapeutic purposes. The Pericardium meridian has the fewest number of points, nine, while the Urinary Bladder has the most, sixty-seven.

They all have vertical trajectories, meaning they are more or less perpendicular to the ground when you are standing up. The Hand meridian end points, either the first or last point on any given meridian, are found at or very near the tips of the fingers, while the Foot meridian end points are found at or very near the tips of the toes. The Foot meridians do not travel directly into the arms, and the Hand meridians do not travel directly into the legs. Both do necessarily enter the torso, since each communicates with its associated internal organ. The Hand and Foot Yang meridians traverse the external part of the head and have points that may be needled there. They end inside the brain. The Hand and Foot Yin meridians also end in the brain, but they are entirely internal to the head and have no points able to be needled there. Yin-Yang theory will be discussed in detail in the next chapter.

Figure 2.1 (Acupuncture Meridians)

The twelve regular meridians are bilateral. Each meridian enters and communicates with its associated organ, which gives the meridian its name.

The Twelve Regular Meridians

|

Common Meridian Name |

Yin/Yang Type |

Chinese Meridian Designation |

|

Lung Meridian |

Hand Yin |

Hand Taiyin |

|

Large Intestine Meridian |

Hand Yang |

Hand Yangming |

|

Stomach Meridian |

Foot Yang |

Foot Yangming |

|

Spleen Meridian |

Foot Yin |

Foot Taiyin |

|

Heart Meridian |

Hand Yin |

Hand Shaoyin |

|

Small Intestine Meridian |

Hand Yang |

Hand Taiyang |

|

Urinary Bladder Meridian |

Foot Yang |

Foot Taiyang |

|

Kidney Meridian |

Foot Yin |

Foot Shaoyin |

|

Pericardium Meridian |

Hand Yin |

Hand Jueyin |

|

Sanjiao Meridian |

Hand Yang |

Hand Shaoyang |

|

Gall Bladder Meridian |

Foot Yang |

Foot Shaoyang |

|

Liver Meridian |

Foot Yin |

Foot Jueyin |

The names in the left column are the common meridian names. You can see how they are named exactly for their associated organ. The center column supplies the basic designation, showing whether the meridian is a Hand or Foot, Yin or Yang meridian. The right column provides a more specific Chinese designation for each meridian, and additionally indicates the meridian’s relative depth. Yang meridians are more superficial, and Yin meridians are deeper, so the most superficial is the Yangming, and the deepest is the Jueyin. (Note that there is not universal agreement about meridian depth. Some sources say the Taiyang meridian is the most superficial.) Shaoyang is considered to be “half external, half internal,” since it is at the most medium depth.

This is also a type of flow chart, depicting the order in which Qi flows through the meridian system, beginning with the Hand Taiyin and ending with the Foot Jueyin, which then cycles back to Hand Taiyin. The last point on the Liver Foot Jueyin meridian, Liver 14, is called Qimen, which translates to “Cycle Gate,” to indicate this very function. It has been calculated that it takes Qi approximately twenty minutes to travel through the entire meridian system and return to its starting point. This is why a typical acupuncture treatment lasts approximately twenty minutes or multiples of twenty minutes. Note there are therapeutic reasons why a treatment may last longer or shorter than twenty minutes.

The last bit of information to consider in the meridians chart is that each meridian/Organ System appears as a part of a Yin-Yang organ pair. The Lungs and Large Intestine are a Yin-Yang organ pair, as are the Liver and Gall Bladder, and all the other organ pairs in between. Yin-Yang organ pairs have a strong interrelationship and a unique affinity for each other, and what affects one will most readily influence the other. There are special acupuncture points, called Luo Xue, or connecting points, that directly connect the Qi of a Yin organ to its paired Yang organ and the Qi of the Yang organ to its paired Yin organ.

The Qi that flows through the meridians is called Jingluoqi (Jing-Luo Qi), which simply means “vessels and collaterals Qi.” “Vessels” is yet another name for meridians and channels. Collaterals are fine horizontal meridians that form an energetic mesh throughout the body and are a main way through which the Qi of the regular meridians interconnect. Collaterals do not contain acupuncture points. Zhenqi (Zhen Qi) or Zhengqi (Zheng Qi), “normal Qi” or “upright Qi,” is another name for the Qi that flows through meridians. Zhenqi also exists throughout the body, outside of the meridian system, so Jingluo is the name most used to differentiate Qi within the vessels. Jingluoqi is the Qi that is directly influenced by a standard acupuncture treatment and is the Qi that’s primarily accessed in any meridian-based medical Qigong.

Jingluoqi manifests in ways that are related yet different from the Qi of its associated organ. So it’s entirely possible for there to be a problem with the Lung Jingluo meridian Qi, but the Lung organs may be functioning normally. Since there’s a strong connection between the meridian and organ Qi, a problem in one, left uncorrected, will eventually result in a problem in the other. This may be understood easiest when considering that with acupuncture, the Qi of the organ is accessed through its associated meridian. In other words, an organ is never intentionally directly punctured by an acupuncture needle, only its meridian, and that’s what ultimately effects change within the organ.

The Eight Extraordinary Meridians

In addition to the twelve regular meridians, there are eight extra or extraordinary meridians. Some texts refer to them as “psychic” meridians, because their effects can be extremely profound and tap into deeper, subtler aspects of being. In a standard medical context, they have more conventionally practical applications, and they may be especially beneficial in instances of emotional, psychological and constitutional issues.

In clinical practice, the two most common Extraordinary Vessels are the Du Mai, or “Governing Vessel,” and the Ren Mai, or “Conception Vessel.” The Du runs up the centerline of the back of the body and influences all the Yang meridians and the entirety of the body’s Yang Qi, and the Ren runs up the front centerline of the body and influences all the Yin meridians and the entirety of the body’s Yin Qi. The lower portions of Du and Ren meridians connect near the perineum, and the upper portions connect where the tip of the tongue touches the roof of the mouth, just behind the upper teeth. Each has its own acupoints that can be needled.

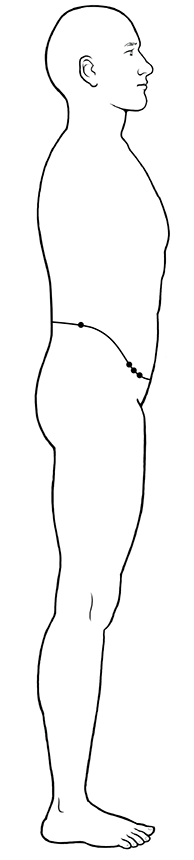

The next most commonly used of the Extraordinary Vessels is the Daimai (Dai Mai), or “Girdling Vessel.” This is the only meridian that has a horizontal trajectory around the body. It intersects the lower Dantian (the main energy center of the body, located two to three inches below the navel), rising slightly to travel over the iliac crest (the tops of the sides of the pelvis bone) and then running straight back to cross the spine at the height of the lower border of the second lumbar vertebra. (See Figure 2.2 on next page.) As its name implies, it “girds,” or binds and stabilizes, all the vertical meridians, aiding in their intercommunication. While it has no discrete acupoints of its own, it can be needled more or less directly through intersecting points on other meridians, primarily the Gall Bladder meridian. Because of its connections with all of the vertical meridians, it has a wide range of influence, but it is most commonly used in treating gynecological and reproductive disorders.

The remaining five Extraordinary Vessels include the Yin Wei (Yin Linking), the Yang Wei (Yang Linking), the Yin Qiao (Yin Heel), Yang Qiao (Yang Linking), and the Chong Mai (Penetrating Vessel). None of these has its own discrete acupoints, but they may be treated through intersecting points on other meridians.

Figure 2.2 (The Daimai)

The Yin and Yang vessels are complementary pairs with related balancing functions. The Qiao vessels end in the eyes and influence whether the eyes want to remain open and wakeful or closed and sleepy. They also influence the muscles of the legs and may be used to treat flaccid (very loose) or hypertonic (very tight) muscles on the Yin or Yang surfaces of the legs, respectively. The wei vessels connect, or link, all the Yin meridians and Yang meridians, respectively. Accordingly, they have a wide range of applications and provide a great deal of flexibility in treatment options. For example, since the Du meridian influences all the Yang meridians, and the Yang Wei has points of intersection on the Du meridian, select Yang Wei intersecting points can enhance the effect of Du points in any given treatment.

The Chong Mai has a number of distinct pathways within the body but generally runs along the centerline of the body, close to the Ren and Kidney meridians in the front, and along the lower portion of the Du in the back. It also has a wide range of treatment applications, but since it grows out of the Kidneys and has a special affinity for the Ren, it can be used very effectively when combined with Kidney and Ren points. Among other possibilities, this is useful in treating gynecological, reproductive, and digestive disorders and is very beneficial in cases of constitutional weakness.

Meridians and Western Medicine

Since meridians are nonphysical and exist only to transport Qi, it’s easy to understand why they are not contained in the Western medical paradigm. That does not mean there are no Western correspondences or verifications, only that when there is any Western medical interpretation considered at all, it is understandably biased toward a Western mindset.

For example, the lower portion of the Gall Bladder meridian (and the small portion of the Urinary Bladder meridian that is present at the sacrum) lies over regions of the sciatic nerve. When acupuncture is used to relieve sciatic nerve pain, the Western interpretation usually invokes gate control theory, also known as nerve gate theory, which states that a nerve can only effectively transmit one signal at a time, so the stimulus from the acupuncture needle overrides the preexisting pain stimulus of sciatic neuralgia, dulling the patient’s perception of the sciatic pain. There are at least two problems with that interpretation, though.

First, no nerve is ever intentionally needled during an acupuncture treatment. A meridian is not the same thing as a nerve, even when they exist in close proximity. Second, the acupuncture needle may induce some sensation, but an acupuncture needle is so thin that the sensation produced by directly stimulating the nerve would not be able to overwhelm the much greater sensation of sciatic nerve pain.

Similarly, the portion of the Stomach meridian that runs through the cheek and jaw overlays the lymph vessels and portions of the trigeminal nerve in that same region of the face. The effects of the facial Stomach meridian points are clearly not mediated by the lymph system, and the same criteria cited for the sciatic nerve apply here for the trigeminal nerve.

Qi has already been discussed as the material foundation for everything in existence, which includes everything in the body. The meridians are vessels that contain and transmit Qi. Chinese medical thought includes the idea that the presence of energy, Qi, precedes all material manifestation, and from that point of view, the meridians helped form the physical structures they overlay. Therefore, effecting a change in the Gall Bladder meridian can easily influence the sciatic nerve, and effecting a change in the Stomach meridian can influence the functioning of the local lymph system and the trigeminal nerve. This is exactly the reverse of the Western medical view, when acupuncture is considered to be therapeutically effective at all.

A commonly cited reference of scientific proof of the existence of meridians discusses the injection of a radioactive dye into acupuncture points and the observation of the dye’s progression along established acupuncture meridian pathways that have no other known physical, anatomical counterpart. In 1985, French scientist Pierre de Vernejoul at the University of Paris conducted this definitive experiment.4 He injected the radioactive marker technetium-99m into subjects at classic acupuncture points. Using gamma camera imaging, he tracked the subsequent movement of the isotope, which showed that the tracer followed the linear trajectory of traditional meridian lines, traveling a distance of thirty centimeters in four to six minutes. (It should be noted here that the physical substance, while traveling relatively quickly and exactly following the acupuncture meridians, traveled more slowly than the Qi that moved it along.) As a control, he made a number of random injections into the skin, not at acupuncture points, and injected the tracer directly into veins and lymphatic channels as well. There was no significant migration of the tracer at sites other than acupuncture points.

One of the most groundbreaking Western researchers in bioelectricity, taking into account both Western and Eastern perspectives, is Dr. Robert O. Becker. In his first book (coauthored with Gary Selden), The Body Electric: Electromagnetism and the Foundation of Life,5 he reports an experiment he conducted in the late 1970s with biophysicist Dr. Maria Reichmanis, in which they used thirty-six electrodes to measure the electrical conductivity of acupuncture points along the traditional pathways of the Large Intestine and Pericardium meridians. They predicted they would find lower electrical resistance, greater electrical conductivity, and a direct current (DC) power source detectable at each acupuncture point. Becker had earlier found the DC system of the human body, which gets more negative at the fingers and toes and becomes more positive in the torso and head. This is an objective, scientific correspondence to the Yin (negative) and Yang (positive) flows within the acupuncture meridians. Becker and Reichmanis found their exact predicted changes at half of all the acupoints tested, with the same points showing up as active on all people tested. They also found that the meridians were conducting current and its polarities, with the acupuncture points being positive relative to the surrounding tissue, and that each point exhibited a distinctive surrounding field. Finally, they found a fifteen-minute rhythm to the current’s strength at the active points.

The Large Intestine (Hand Yangming) and Pericardium (Hand Jueyin) meridians are found on the arms, easily accessible for research purposes. Although not stipulated in the report, that’s probably the reason they selected those particular meridians. Similar findings would reasonably be expected along any meridians selected. Although the electrical changes were found on half the points examined, the researchers posited that the other half may have had weaker fields or emitted a different type of energy than they were looking for. Another likely possibility, which is only conjecture because the particular active points were not disclosed in the report, is that the unresponsive points may have been deeper within the body. The researchers were specifically looking at superficial skin resistance and electrical changes.

The directionality of electrical flow found by Becker and Reichmanis is an important corroboration of the directionality of meridian Qi flow, as each meridian has its own directional trajectory, and the electrical polarities imply the corresponding polarities of Yin and Yang. Finally, the fifteen-minute cyclical rhythm of current strength is an intriguing correlation with the long-held understanding that Qi flows through the entire network of acupuncture meridians in approximately twenty minutes, with some time variability based on room and seasonal temperature—warmer equaling a faster transit time—and the relative health and makeup of the individual. An acupuncture treatment commonly lasts for twenty minutes or multiples of twenty minutes for this reason, with treatments being shorter in warmer weather or for particular therapeutic purposes. Some alternate needling practices, such as Bagua needling techniques based on the Yijing (I Ching), require a twenty-eight-minute treatment time, approximately twice the fifteen-minute period noted by Becker.

Many similar Western studies have been conducted and published in the intervening years, and it’s likely that trend will continue, especially as Western technology becomes better able to detect increasingly more subtle biological energies. The studies by de Vernejoul and by Becker and Reichmanis remain among the most compelling to date.

4. Pierre de Vernejoul, Pierre Albarède, and Jean Claude Darras, “Nuclear Medicine and Acupuncture Message Transmission,” The Journal of Nuclear Medicine 33, no. 3 (March 1, 1992): 409–12.

5. Robert O. Becker and Gary Selden, The Body Electric: Electromagnetism and the Foundation of Life (New York: Quill, 1985), 235–36.