Third Concept:

Yin and Yang, Polarities, and Balance

Yin and Yang might be the most familiar of these concepts in the Western world, at least superficially, since it is represented by the popular Taiji (“supreme ultimate”) symbol, colloquially known as the Yin Yang symbol, or simply “the Yin Yang” (Figure 3.1). Its most striking features include its black (Yin) and white (Yang) halves, representing the complementary balancing opposites that underlie all related phenomena; the small dot of black Yin existing within the large white Yang region, with the corresponding small white dot of Yang within the larger Yin region, demonstrating that everything contains the seed of its opposite and that there is nothing that is purely Yin or Yang; and the curved line that both separates and unifies the opposing halves.

Figure 3.1 (Taiji Symbol)

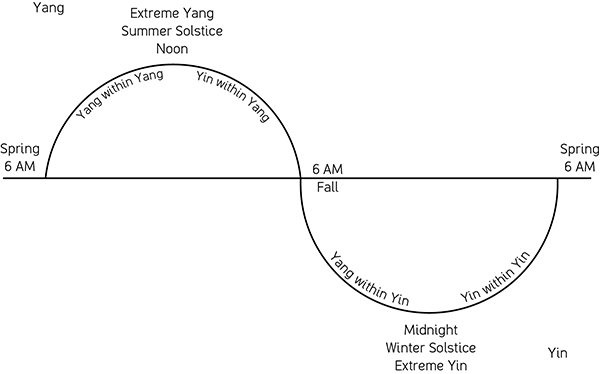

Figure 3.2 (Yin Yang Sine Wave)

The basic principle of Yin and Yang is that of the dynamic balance, the equilibrium, that exists throughout the natural world. That dynamism is indicated by the curved line between the opposing halves of the Taiji mandala. If you were to lay it on its side, you would see that it forms a familiar sine wave centered on the horizontal axis (Figure 3.2). It implies fluid, dynamic movement between alternating states, with the peak being most Yang (or positive) and the trough being most Yin (or negative). Yin and Yang are therefore not static and lifeless, which could be represented by a straight line between the two. The symbol indicates process, change, and the way things evolve over time through the interplay of equal opposites, which are intrinsic to all Yin and Yang pairs.

From the holistic perspective, this means that no one thing can exist in complete isolation: it always exits in relation to its balancing, complementary, polar counterpart (the holistic microcosm) and ultimately in relation to the universe as a whole (the holistic macrocosm). The part can only exist in relation to the whole. One of the earliest schools of thought devoted to the study of Yin and Yang was sometimes referred to as the Naturalist School, since it strove to understand and then use nature’s laws for the betterment of humanity, by learning to live in harmony with those principles, the holistic approach. This is in direct contrast to the prevailing trend of Western science to control and manipulate nature.

Yin and Yang in the Natural World

All natural events and states of being can be observed and evaluated through the perspective of Yin and Yang, but they don’t refer to any objective, material things. As stated in one of the most widely used contemporary texts about Chinese medicine, Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion, “It is, rather, a theoretical method for observing and analyzing phenomena. … [It is] a philosophical conceptualization, a means to generalize the two opposite principles which may be observed in all related phenomena within the natural world.” 6

After the Taiji mandala, the most direct way to begin to understand the attributes of Yin and Yang is by considering the Chinese characters for both, as we did for Qi. The character for Yin depicts the shady side of a hill, while the character for Yang depicts the sunny side. So the Yang side of the hill displays many of the qualities associated with Yang—being sunny, bright, and warm—while the Yin side displays the complementary Yin qualities—shady, dark, and cool.

Similarly, in Chapter 5 of the ancient Chinese medical text, Plain Questions, it is stated that “Water and Fire are symbols of Yin and Yang.” 7 They are iconic representations that graphically symbolize some of the qualities of Yin and Yang, all the balanced complementary and contrasting polarities that exist. For those completely new to these concepts, please note that as useful as the symbols of Water and Fire are, and all the attributes of Water and Fire are contained within Yin and Yang, not all the attributes of Yin and Yang can be contained within the representative Water and Fire. Similarly, not every attribute of Yang is directly equatable with every other attribute of Yang. Fire is Yang and is also bright and hot, two other Yang qualities, so you can say that both Yang and fire are bright and hot. But male is a Yang quality, and its paired Yin counterpart is female. It would not be strictly correct to say that males are hot and bright, and females are cold and dark.

As on the shady side of the hill, where water is generated as moisture condenses on rock and dew readily forms on plants, water is cool and dark. It also displays other Yin qualities, such as stillness and a downward and inward directionality, as it tends to gather, pool, and is readily absorbed by dry earth. Like the sunny side of the hill, fire is hot and bright and possesses the additional Yang qualities of activity and an upward, outward directionality.

There are four primary aspects applicable to all Yin and Yang pairings, and these occur in their every manifestation, both in the outer world and within the body.

Four Primary Aspects of Yin and Yang Pairings

1. The Opposition of Yin and Yang

2. The Interdependence of Yin and Yang

3. The Mutual Consuming/Supporting Relationship of Yin and Yang

4. The Intertransformation of Yin and Yang.

Another aspect, sometimes cited as the fifth aspect, is the Infinite Divisibility of Yin and Yang. This is a way of saying that Yin and Yang are completely relative terms and not independent absolutes. Anything seen as Yang can always be further divided into Yin and Yang parts; anything Yin can be further divided into Yang and Yin parts. Whether or not we consider that as a fifth primary aspect, it is undeniably an attribute of Yin and Yang.

In the natural world, we readily see these aspects as interrelated and arising simultaneously. An example for one aspect may readily illustrate another equally well. Let’s examine just a few Yin-Yang pairs to see how that occurs.

|

Yin-Yang Pairs |

|

|

Yang |

Yin |

|

Positive |

Negative |

|

Day |

Night |

|

Summer |

Winter |

|

Yin-Yang Pairs, cont. |

|

|

Hot |

Cold |

|

Light |

Dark |

|

Activity |

Rest |

The Opposition of Yin and Yang refers to them being polar opposites, and the qualities of one half balances or opposes the qualities of the other. We’ve seen how, when laying the Taiji symbol on its side, the resulting sine wave is positive at its peak and negative at its trough, but it is not static. The positive and negative aspects oppose and balance each other. Only at the absolute extremities do we see something that seems purely positive or purely negative, purely Yang or purely Yin. Even there, it is in transition; it does not remain at either extremity. This is a most obvious manifestation of the cyclic process of harmonious change brought about by such opposition.

Conceptually, we cannot have the existence of one half without its balancing counterpart. In addition to the examples given above, other Yang-Yin pairs include up and down, expanding and contracting, outside and inside, above and below, heaven and earth, male and female. One half of a pair is meaningless without its opposite.

In practical application, the opposing qualities of Fire and Water are commonly used in daily life. Water is used to put out unwanted or dangerous fires. When washing clothes, water is used to cleanse them, but they are then also Yin—cold and wet. The hot attribute of Fire, either from the very Yang sun or the electric clothes drier, is applied to them until they are warm and dry. The Yang characteristics of day and of summer are similar. They are both hot and light relative to their respective Yin counterparts, night and winter, which are cold and dark. The extremes of a day are comparable to the peak and trough of the sine wave, noon and midnight, respectively. As in the sine wave, day cycles into night, and night back into day. This is a manifestation of their interdependence. As with the Opposition of Yin and Yang, you cannot have one without the other.

When we look at the Mutual Consuming/Supporting Relationship between Yin and Yang, we again have to take into account their polarity or opposition and their interdependence. This is because the consumption and support depend on the ability of Yin and Yang to exert beneficial controls on each other, as only interdependent polarities can. Analyzing the diurnal cycle from a Yin-Yang perspective, noon is “Extreme Yang.” As the daytime wanes and moves toward night, it is still Yang time, but Yin grows. This is called “Yin within Yang,” as Yin begins to consume Yang. Dusk is a time of balance, when neither Yin nor Yang predominate, and is comparable to the sine wave crossing the horizontal axis, when it is neither positive nor negative. After dusk, night is entered and Yin continues to grow. This period of time is called “Yin within Yin.” Nighttime peaks at midnight, “Extreme Yin.” After midnight, it is still nighttime, Yin time, but moving toward daytime, and Yang begins to grow, or consume Yin. This is called “Yang within Yin.” At dawn, neither Yin nor Yang predominates, and there is an instant of pure balance as the sine wave crosses the horizontal axis once more. As the sun rises to bring forth the daytime, Yang once more grows toward its noontime peak. This is called “Yang within Yang.” At noon, Yang peaks, and the cycle begins again. This same cycle exists on a longer twelve-month scale when analyzing seasonal transitions, with midsummer being Extreme Yang and midwinter being Extreme Yin, most precisely on the summer and winter solstices. Figure 3.2 provides a graphic representation of these cycles.

The above example also introduces the Infinite Divisibility or complete relativity of Yin and Yang. Dusk is more Yang than midnight but more Yin than noon. Three in the afternoon is a Yang time, but as Yin grows within Yang, it is more Yin than eleven in the morning, a Yang within Yang time that is very close to noon.

The Mutually Consuming/Supporting Relationship of Yin and Yang goes along with the Interdependence of Yin and Yang and may be best understood when we consider that the concept of Yin and Yang is first and foremost about balance, a healthy equilibrium. If daytime existed unabated, without the balancing influence of nighttime, there would be too much heat without cooling, too much activity without rest, too much Fire without Water. This would damage all plant and animal life. If the supportive, balancing Yin qualities were not introduced to control the excessive Yang, before long all life on the planet would end. Conversely, if nighttime continued unabated without the balancing support of day, the cold would become oppressive, there would be too much rest without activity, there would be no sunlight allowing plants to photosynthesize, and all life on the planet would end.

Keeping with the previous natural world examples, we’ve seen the Intertransformation of Yin and Yang as day, summer, warmth, and light transform to night, winter, cold, and dark, and back again. Intertransformation is also implied by the small black dot of Yin within the white Yang half of the Taiji symbol and the small white dot of Yang within the black Yin half. The fact that Yin and Yang are not absolutes, each containing the seed of the other, allows for that seed to grow and eventually transform one into the other. Even at high noon, the most Yang time of any day, on the hottest, brightest day imaginable, you can still find shadows, small patches of cooler darkness—the Yin aspect within the Yang. Likewise, at darkest midnight, the most Yin time, you can still see the twinkle of stars in the sky, the light of Yang within the Yin.

Yin and Yang within the Body

The principles and attributes of Yin and Yang within the body are identical to those in the natural external world. The examples will differ, and the consequences of imbalance may manifest differently as appropriate to the physiology of a body.

One of the main principles that is foundational to all of Chinese medicine, regardless of style or school of thought, is called the Eight Principles. It uses Yin and Yang as a broad-stroke diagnostic tool in order to determine the primary nature of a pathology. While examining the Eight Principles, we’ll introduce some basic diagnostics that relate to them.

|

The Eight Principles |

|

|

Yin |

Yang |

|

Interior |

Exterior |

|

Cold |

Hot |

|

Deficiency |

Excess |

Putting Yin and Yang at the top of the list serves both as a heading for the six principles that follow and as an umbrella to cover all other Yin and Yang imbalances that may exist when differentiating pathological syndromes. In general, a preponderance of Yin will make a person feel withdrawn (interior), cool or cold (a pale complexion or frank pallor is a common manifestation), and lethargic or sleepy (deficient). A preponderance of Yang will make a person boisterous or aggressive (exterior), warm or hot (a red face is a common manifestation), and very energetic or agitated (excessive).

The Interior and Exterior pairing has to do with location and is relevant to both the natural state of the body and to the nature and progression of a pathology. While all organs are internal, Yin organs are naturally deeper, more interior, while Yang organs are more superficial, since each communicates with the external world through the mouth, anus, and urethra.

Related to Interior and Exterior, the relatively synonymous pairing of Deep and Superficial may make some examples more clear. The skin and muscles are superficial, on the exterior portion of the body, relative to all the internal organs. Yang is naturally protective, and these superficial body tissues protect the more delicate, deep, internal structures from external pathogens and physical harm. Skin is the level at which Weiqi (Wei Qi), “defensive Qi,” circulates, protecting the body from external pathogens. In Western terms, the skin is the acid mantle that protects against bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens as part of the first line of immune-system defense. Muscles are hard relative to the soft internal organs, as are the more superficial bones of the ribs and vertebrae, and are protective against physical injuries.

Pathologies that appear on the skin or primarily affect the exterior portions of the body, like eyes and nose, are exterior. Generally, they are early-stage imbalances and not very severe at that point. Both the common cold, caused by an external pathogen (whether environmental, according to Chinese thought, or germs, according to Western medical germ theory), and a poison ivy rash, caused by physical contact with an external irritant, are examples. Deeper yet still relatively external pathologies may affect the muscles, tendons, ligaments, superficial blood vessels and nerves, or meridians. Internal pathologies may occur when an external pathogen progresses deeper into the body, or they may arise from an internal imbalance due to constitution, prolonged emotional states, poor nutrition, parasites, or poisoning or as a side effect of a pharmaceutical drug. They will affect the internal organs, deep blood vessels and nerves, blood, brain, spinal cord, and bones. Note that many deep pathologies will cause secondary changes to superficial body parts such as skin and eyes and may appear similar to exterior pathologies. Other diagnostic criteria will distinguish between them.

Some schools of Chinese medical thought once attempted to analyze all disharmony (disease) through its relative depth within the body and designed the Four Level diagnosis. Those four levels include Wei (protective and most superficial), Qi (the level of meridian Qi, deeper), Ying (nutritive Qi, deeper still), and Xue (Blood level, the deepest and most severe). A common cold exists superficially at the Wei level or sometimes at the Qi level if it’s a very bad cold. Graphic examples of Xue-level conditions include biomedically defined diseases such as hemophilia, tuberculosis (at the point at which the patient begins coughing blood), and hemorrhagic fevers. Four Level diagnosis is rarely if ever used exclusively these days, but it is still relevant in helping to determine the relative depth of a pathology along the continuum of Interior and Exterior, which strongly influences treatment choices.

The next pairing of principles, Cold and Hot, seems easier to understand from a diagnostic perspective. We’ve already seen that both day and summer are Yang, and are warm or hot relative to night and winter, which are Yin and cool or cold. So a person who is habitually cold or feels chilly easily might be more constitutionally Yin, while a person who is habitually hot or likes to avoid warm environments might be constitutionally Yang. An imbalance that creates a feeling of cool or cold, producing chills, might be a Yin pathology, while one which produces a fever might be a Yang pathology.

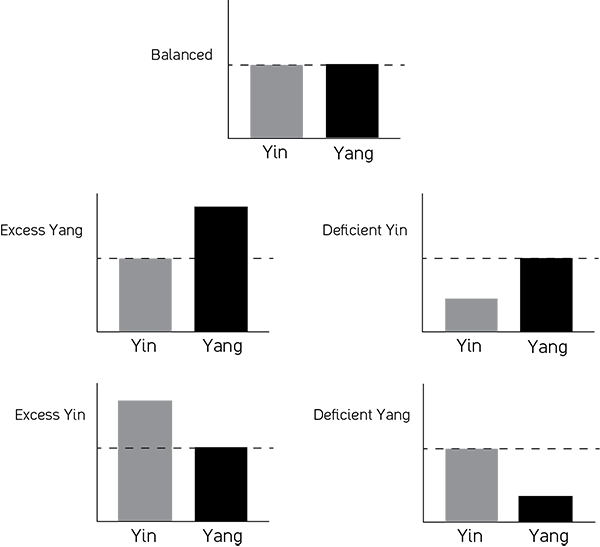

In the simplest textbook-perfect scenarios, the above examples would be exactly true, but I’ve purposely used the words “seem” and “might” as equivocations because this is one area where things can get tricky due to the relativity of Yin and Yang. That trickiness becomes easier to understand when we introduce the principles of Deficiency and Excess. In a perfectly balanced, healthy body, Yin and Yang exist in equal, if dynamic, proportions. We see that represented on the next page in Figure 3.3 by Yin and Yang appearing “topped off” in equal measure at the horizontal line of complete balance. In the conditions of a preponderance of Yin or preponderance of Yang described earlier, either the Yin or the Yang column would grow upward of the horizontal axis, into the positive, or excess, regions. Then, Excess Yin would produce Cold symptoms, and Excess Yang would produce Hot symptoms. In these cases, an excess of Yang will create a deficiency of Yin, as Yang consumes Yin in the way heat will dry up a puddle. An excess of Yin will cause a deficiency of Yang, Yin Consuming Yang, as water can douse a flame.

Figure 3.3 (Yin Yang Balance, Deficiency, and Excess)

It’s just as possible, though, for there to be a deficiency of Yin or Yang. In the case of Deficient Yin, the Yin column would shrink below the dotted horizontal line and into the deficient region. Then, even though Yang would not be in excess and might stay exactly at the dotted horizontal line, it would be greater than Yin and produce feelings of Heat. This is an example of Deficiency Heat, since Yang would not be in excess. Conversely, Yin may stay at a normal, balanced level, but Yang may shrink below the dotted line, leading to feelings of Cold. This is an example of Deficiency Cold, since Yin would not be in excess. Whether due to Deficiency or Excess, the feelings of Cold or Heat are due to Yin and Yang being out of balance.

We’ve learned that daytime is Yang and nighttime is Yin. Here we can consider that a truly Yang condition of Excess Heat is likely to get worse during the daytime, Yang time, and a little better at night, Yin time. This is because as the Yang energy naturally increases during the daytime, its warmth would add to the warmth of the Yang pathology, making it feel worse, while the cooling energy of Yin, which flourishes at night, would balance some of the excess heat, so it would feel a little better. The converse is true for a Yin condition.

In the case of Deficiency Heat, the opposite occurs. If Yin energy is weak or deficient, leading to Deficiency Heat, the Heat symptoms would worsen at night. This is because the Yin energy is too weak to flourish during nighttime, Yin time, so its cooling influence would not be able to balance the warming energy of Yang, which would flourish unabated.

Deficiency and Excess can occur apart from overt associations with Heat and Cold, of course. “Deficiency” means a reduced functional energy and lowered capacity of any organ or physiological process. “Excess” means an abnormally high level of functional energy of any organ or physiologic process. It may occur along with an obstruction, since Qi, Blood, or body fluids can build up and become an Excess accumulation if they are obstructed from their normal patterns of flow.

When discussing the body, some other useful Yin-Yang pairings include below and above, front and back, Blood and Qi.

The lower part of the body (below the waist) and the front of the body are both more Yin, while the upper body (above the waist) and back of the body are more Yang. Leaving aside any diagnostic considerations for now, let’s look at some of the factors that make this so. To see this most clearly, we need to introduce two related ideas.

The first is that Heaven, or anything celestial, is more Yang relative to the Earth, which is more Yin. Heaven and Earth is a Yang-Yin pairing. The second is that Chinese anatomical position, the position in which a person stands to accurately display the energetic aspect of anatomy, is in a hands-up position, or the stereotypical “I surrender” position, with arms extended above the head with palms facing forward. In this position, the head is naturally nearer to the sky, more Yang, while the feet are naturally closer to the earth, more Yin. The backs of the hands and arms face rearward, more Yang, while the palms and front of the arms face forward, more Yin.

Next, let’s consider the external trajectory of the meridians themselves and see how that further ties in with Heaven and Earth and with Chinese anatomical position. All of the Hand Yang meridians begin at the fingertips (just outside the corner of the nail beds), travel down the back (Yang side) of the arms, and end in the head. All of the Foot Yang meridians begin in the head. Two of the three travel down the back (Yang side) of the torso. The Stomach meridian is the exception, the Yang within the Yin, and travels down the front of the torso. (While being a Yang organ, one of the main functions of the Stomach is a Yin one, that of supplying nourishment to the rest of the body. Its appearance on the Yin surface of the body is accordingly not very surprising nor truly anomalous.) The Gall Bladder (Foot Shaoyang) meridian zigzags a bit between Yin and Yang at the side of the torso, but stays primarily Yang. All travel down the backs and outsides (Yang sides) of the legs and end at the toes, at the corner of nail beds. In both the Hand and Foot Yang meridians, this is a downward flow of Qi, from Heaven to Earth.

All the Hand Yin meridians begin in the front of the torso, travel up the front (Yin side) of the arms and hands, and end at the fingertips, just outside the corner of the nail beds. All the Foot Yin Meridians begin at the tips of the toes at the corner of nail beds (the exception being the Kidney meridian, which begins on the sole near the ball of the foot), travel up the front and inside (Yin side) of the legs, up through the front of the torso, and end at the front of the torso. The Spleen meridian ends at the border between the front and back of the chest, behind the Gall Bladder (Shaoyang) meridian, and is the closest a Yin meridian gets to being the Yin within the Yang. In both the Hand and Foot Yin meridians, this is an upward flow of Qi, from Earth to Heaven.

Keep in mind that Yin and Yang are polar energies. Yin Earth wants to flow toward Yang Heaven; Yang Heaven wants to flow toward Yin Earth. The human being is one conduit through which that can occur, mediated by the energetics of the body. This principle is used extensively in many Qigongs and is one way in which physical movement influences Qi flow.

As integral components of body substance (matter) and function (energy), Blood and Qi are an interesting Yin-Yang pair. Most simply, Blood is Yin and Qi is Yang. Blood is a liquid material that carries nutrients, oxygen, various chemical messengers, and the physical aspects of the immune system to every cell in the body. It also carts away cellular waste products for disposal or recycling. Being fluid, it can moisten and lubricate body tissues. Qi is the sum of all the functional energy in the body, is warming and energizing, and is involved in all activity, thought, perception, and emotional experience.

It may seem very clear that Blood is exclusively Yin and Qi is exclusively Yang until we remember that Qi is also the material foundation for everything in existence. Some Chinese medical texts refer to Blood as the material form of Qi. Qi itself can be divided into Yin Qi (which is cooling, calming, and nourishing) and Yang Qi (which is warming, exciting, and active). As a Yin-Yang pair, the line between Blood and Qi may get blurred at times, but each instance of that apparent blurring has valuable therapeutic, health-building reasons.

For the most part, for our purposes we will keep them distinct. The Chinese medical phrase “The Qi is the commander of the Blood; the Blood is the mother of the Qi” embodies their mutual support and interdependence while keeping them more clearly defined as separate Yin-Yang entities. “The Qi is the commander of the Blood” means that Qi is responsible for directing every aspect of Blood movement throughout the body. This includes things like the heart’s stroke volume, the speed and directionality of blood flow, blood sufficiency, venous return, and so on. “The Blood is the mother of the Qi” means that within the body, Qi needs a material foundation out of which to grow. The Blood supplies that substrate. When the Blood is deficient in any way, the Qi will be weak. If there is no Blood, there can be no Qi.

Western Correspondences to Yin and Yang

Western science and medicine does not overtly employ Yin-Yang theory, but we can look at some Western ideas that exemplify those principles nonetheless. We’ve seen that in the Taiji symbol, there is a seed of the Yin within the Yang and a seed of the Yang within the Yin. Men are Yang, and women are Yin. The primary male hormone is testosterone, which prenatally determines the sex of the fetus and then from puberty onward causes the male secondary sex characteristics, including increased body hair, deepening of the voice, thickening of the skin, increased muscle growth, and thickening and strengthening of the bones. One of the primary female hormones is estrogen, which along with progesterone is responsible for the female secondary sex characteristics, including the development of breasts, increased percentage of body fat, and an increased vascularization of the skin. Yet women’s bodies produce small amounts of testosterone in the ovaries and adrenal glands that contribute to the female sex drive as well as maintain bone and muscle mass. This is the Yang within Yin, the seed of Yang on the Yin side of the Taiji mandala.

Men’s bodies also produce small amounts of estrogen, converted from circulating testosterone, and it can be produced in the liver and muscle cells. Fat cells produce estrogen in both men and women. From the Chinese perspective, fat is a very Yin substance, so it is not surprising that it generates a very Yin molecule, estrogen. The role of estrogen in men’s health is not entirely clear, but aging men with moderate estrogen levels seem to have fewer heart problems and better bone density than men with very low or very high estrogen levels. (As with all things Yin and Yang, balance is the key!) This is the Yin within the Yang, the seed of Yin on the Yang side of the Taiji symbol.

Another example involves nerve conduction, the way nerve impulses are transmitted. In simplest terms, each nerve cell receives an impulse, or charged stimulus, from the nerve cell next to it. The cell in its resting state is polarized—off and Yin. When it receives an impulse from an adjacent nerve cell, it depolarizes and becomes active and Yang. It transmits the impulse to the next adjacent nerve cell and then returns to its polarized, resting Yin state. This rapid depolarization/polarization of adjacent nerve cells, the alternation between Yin and Yang states, is what allows the impulse to be transmitted along the length of nerve pathways and is what’s responsible for virtually every move we make (both voluntary and involuntary, or autonomic), every sensory input we experience, and thought itself—just from the simple alternation of off and on, negative and positive, Yin and Yang.

When first encountering Yin-Yang theory, many Westerners believe that the two aspects or states of being, Yin and Yang, are too simple, too limiting to be of any real value in defining and regulating something as complex as human health and human biology, let alone being an operating principle underlying the totality of life and everything in the universe. But consider that in the realm of modern technology, all things digital rely on just two numbers, zero and one. These are the “digits” to which the term “digital” refers. Binary code underlies the operation of every computer and computer-controlled device. It’s responsible for all the audio and video presentation on your computer and TV, literally everything on the Internet, all the music you hear on your MP3 player, all the data stored on CDs, DVDs, and hard drives, the diagnostic and other control mechanisms in your car, your cell phone communication and all satellite communication, all electronic financial transactions and security, and on and on.

Someone who is not a computer programmer may not know exactly what is being turned on and off, being placed in alternating states, by those zeros and ones. The hardware can change, and the complexity of manifestations and applications is accomplished in part by extremely long strings of zeros and ones, but at its essential level, that’s all it is: the binary code of Yin and Yang.