Four years after the Civil War, the United States is joined from coast to coast by a transcontinental railroad as a ceremonial final spike is driven at Promontory Summit, Utah. Travel time from the Atlantic to the Pacific will soon fall from as much as six months down to one week.

In an early example of a staged media event, two locomotives sat a mere rail tie apart from each other as crowds of people looked on. Railroad financier and former California governor Leland Stanford drove a single golden spike into the final tie with a silver hammer.

The rail lines from east and west were joined. A telegraph operator let the whole country know with a single message: “DONE!”

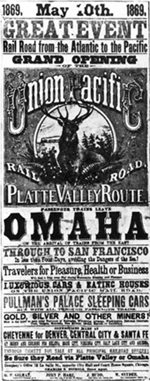

Congress had ordered the rail line built seven years earlier because westward expansion had been hampered by the dangerous wagon-train journey over the Oregon and California trails. The Central Pacific Railroad built the line eastward from Sacramento, California, and the Union Pacific built westward from Council Bluffs, Iowa. Mountains, rivers, and the Civil War dictated where the rail lines could be built.

The Central Pacific relied on recent Chinese immigrants from California and Mormon laborers from Utah to perform the often deadly work of installing rail ties and blasting through mountains. The Union Pacific hired Civil War veterans and recent Irish immigrants.

After the joining ceremony, the golden spike was removed, to be replaced with a normal steel spike. And it was another year before bridges and extensions created an all-rail link from Atlantic to Pacific.—KB