Foreign investment in farmland and the new scramble for Africa. Win-win or dangerous folly?

On 26 January 2009 a curious rice ceremony took place in one of the air-conditioned palaces of Riyadh. With great fanfare, King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz of Saudi Arabia was presented with a bowl of cooked rice. It was part of the first crop from a farm in Ethiopia that had been established by Saudi investors under the auspices of the King Abdullah Initiative for Saudi Agricultural Investment Abroad. Spooked by the near-collapse of world food markets in 2008, and running out of water at home, the oil-rich Arab state had decided to acquire land in other countries to grow food. The king liked the quality of the rice and exhorted the assembled ministers and businessmen to redouble their efforts.

The man presenting the rice was Sheikh Mohammed Al Amoudi. Listed by Forbes as the world’s sixty-third richest person, he has a grin like Yogi Bear and is known for his extravagant parties. Born in Ethiopia, he moved to Saudi Arabia, gained Saudi citizenship and made a fortune in construction and real estate – he is sometimes described as the world’s richest black man. But he retained close connections with the ruling party in Ethiopia and built up a business empire there spanning hotels, mines, construction and agriculture. When the Saudi government decided to funnel hundreds of millions of dollars towards acquiring farmland abroad, Ethiopia, with its fertile western valleys fed by the Blue Nile, was a prime target. Sheikh Al Amoudi was the natural person to lead the charge.

The Ethiopian government could not have been more welcoming. ‘Why attractive?’ reads one of the glossy posters produced by its investment promotion office. ‘Vast, fertile, irrigable land at low rent. Abundant water resources. Cheap labour. Warmest hospitality.’ Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, the country’s autocratic ruler, was a former Marxist rebel who had firmly converted to capitalist enterprise. Even though 8 million Ethiopians suffer from chronic food shortages, he was ‘very eager’ to promote large-scale commercial agriculture in the country. His officials claimed that Ethiopia had 74 million hectares of land suitable for arable farming but only one-fifth was being cultivated. As a result, they made 4 million hectares available to investors. Legally, the government has the power to give away this territory as all Ethiopian farmland was nationalised by the Communists in the late 1970s. Native farmers use it under licence, so their rights are fragile.

Sheikh Al Amoudi was granted 10,000 hectares for sixty years in a remote, impoverished region called Gambella in the west of the country, a bumpy fifteen hours’ drive from the capital. The plan was to use water from a nearby dam that had been constructed by Soviet engineers as part of a cotton-growing scheme that never materialised. But this was just the start. Over the next ten years, Almoudi hoped to acquire a total of 500,000 hectares across the country. This is a massive area, a quarter the size of Wales. He set up a new company, Saudi Star Agricultural Development, to pursue this goal, promising to invest more than $3 billion and to create 10,000 jobs. To cement his insider status, he appointed a former Ethiopian government minister as chief executive of the new company.

In 2009 giant Volvo trucks and Massey Ferguson tractors began trundling along the dusty roads of Gambella. Saudi Star put in a single order for agricultural machinery with Caterpillar worth $80 million. Land was cleared, and work began on a twenty-mile canal that would carry irrigation water to the property. Engineers and agronomists were brought in from Pakistan. The company started planting rice, using a highly mechanised, input-intensive form of agriculture. This must have been bewildering to the locals who peered through the new gates under the watchful eye of armed guards.

The Ethiopian government insists that the land given to Saudi Star was ‘empty’. But this was not the case. Local Anuak people used it for shifting cultivation, while nomadic Nuer pastoralists grazed their animals in the area. There was a highly developed system of customary rights, under which families knew what land belonged to whom. In addition, several small villages had to be cleared to make way for the new irrigation canal.

Omot Ochan, a member of the local Anuak tribe, is just one person who was affected. Lean and tall, he lives in a straw hut on the margins of the Saudi Star property, by the remains of what was once a sizable village. As bare-breasted women cooked fish on an open fire behind, Omot described how two years earlier the company began chopping down the forest. ‘Nobody came to tell us what was happening.’ The bees, from which he used to make honey, disappeared, as did the animals his family hunted. Now they only had fish to sell, but he feared that the fish would go too once the Saudis drained the wetland. ‘This land belonged to our father,’ Omot bitterly said. ‘All round here is ours.’ He pointed to a distant tree that marked the boundary with the next village. ‘When my father died, he said don’t leave the land. We made a promise. We can’t give it to the foreigners.’

Saudi Star has stepped into a complex inter-tribal conflict in Gambella. The hot, swampy region has always been geographically and ethnically distinct from highland Ethiopia. In the past, the Ethiopian state waged war against Anuak separatists and encouraged highlanders to settle in the region. More recently, the government has tried to clear the Anuak and the Nuer from their land and concentrate them in new settlements, through a programme known as ‘villagization’. Although the government denies any link between this policy and the leasing of land to foreigners, this is contradicted by the statements of local officials. One farmer recounted how government officials told his village: ‘We will invite investors who will grow cash crops. You do not use the land well. It is lying idle.’ The Anuak see the arrival of companies like Saudi Star as yet another step in a process of internal colonisation.

Journalists from around the world, and NGOs such as New York-based Human Rights Watch, have drawn attention to events in this isolated corner of Ethiopia. Observers warned that the sullen resentment of the Anuaks could explode into violence. Sure enough, on 28 April 2012 gunmen opened fire on a group of Saudi Star workers, killing two Pakistanis and three Ethiopians. According to some reports, the farm offices of Saudi Star were ransacked. An organisation called Solidarity Movement for a New Ethiopia issued a statement saying that this was an inevitable reaction to ‘the long term leasing of agricultural land in Ethiopia to foreign investors and regime cronies for next to nothing’. The Anuak are willing to fight to defend their rights, the group said. ‘This should not come as a shock to anyone.’

The story of the Saudi farm in Ethiopia is just one example of a trend that is playing out all around the world. Since 2008 the media has been full of stories about ‘land grabs’. Everyone from Bob Geldof to the late Colonel Gaddafi has spoken out about the menace, warning that it could lead to neo-colonial exploitation. In an absorbing recent book called The Landgrabbers, journalist Fred Pearce warns that it is of more threat to the poor of the world than climate change. Just how widespread is this phenomenon? Is it all bad? Or could foreign investment in agriculture play a positive role in increasing food security, as the Ethiopian President believed? What does it mean for the future of the world’s food system? There is as much hype as reality in media coverage of this topic but, away from the headlines, there is no doubt that something important is going on.

There have been wildly differing estimates of the scale at which farmland is being acquired. In a much-delayed 2010 report the World Bank came up with a figure of 56 million hectares, bigger than the size of Spain. The British aid agency Oxfam trumped this a year later, saying that investors were looking to acquire 227 million hectares, an area one and a half times the size of Alaska. The latest census, prepared by an international coalition of researchers and NGOs as part of the Land Matrix database – and available online – documents 924 deals covering 47 million hectares of land.

There are many problems with these estimates. Reliable sources of data are hard to find because so many of these deals are wrapped in secrecy. The World Bank talks of ‘an astonishing lack of awareness of what is happening on the ground even by the public sector institutions mandated to control this phenomenon’ – which are strong words for a normally cautious institution. Most of the surveys quoted above rely on press reports, with little independent verification. The problem is that journalists looking for stories and activists with a drum to beat have sometimes turned rumour into fact, conjecture into certainty. A stray comment by a government official or an investor about the desire to do something – maybe, in the future, inshallah – gets turned into a confirmed mega deal involving a million hectares. You should not believe everything you read in the papers.

It should also be remembered that these figures contain many domestic deals, that is, land acquisitions by companies or individuals within their own country. At least 300 of the 924 land deals listed in the Land Matrix database are purely domestic. This is not to say that local land grabs are any less worrying than international ones. An Anuak villager in Gambella does not much care whether his ancestral land is taken by a Saudi sheikh or a cotton farmer from highland Ethiopia – the impact is much the same. In Cambodia local businessmen tied to corrupt officials have obtained large concessions for new sugar plantations, driving local farmers from their land, sometimes violently. In addition, local deal-makers may be acting as a front for foreign corporations or simply positioning themselves to flip their land to foreigners at some point in the future. Nonetheless, the focus of this chapter is on cross-border deals, as they reveal the most about how the global food system is changing.

Where are these international ‘land grabs’ taking place? Definitions also matter when answering this question. There has always been foreign investment in developed agricultural powerhouses such as the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. For example, the US Department of Agriculture estimates that foreigners hold almost 2 per cent of American farm or forestland. Foreign acquisitions in these cases are mostly private transactions without government involvement. There are many willing sellers as farmers look to retire. The highly productive, export-oriented farming sectors of these countries are already integrated into global markets. A foreign acquisition may entail a change in ownership but little else.

Foreign acquisitions of farmland in Brazil and Argentina share many of these characteristics. Foreigners are usually buying into large-scale corporate farming enterprises, not pushing indigenous tribes or peasants off the land. (The locals have probably done this already.) There may be a question about whether it makes economic sense to allow foreign interests to control such a strategic resource, but it is a stretch to call these ‘land grabs’. They are transactions between financial equals and the land does not come cheap.

The majority of land deals, however, and the ones that have generated the most concern, look very different. They target poor developing countries where land is cheap or can be obtained for free. They involve a radical change in the nature of land rights, usually a transfer from government or local communities to a foreign company in the form of a long-term lease. Host governments are usually heavily involved as they often hold the rights to the land. And the goal of these deals is to effect a transformation in how the land is used, for example by ploughing up grassland or clearing forest, and planting crops. Often, the ultimate goal is to integrate land that has been used for local subsistence into global commodity supply chains.

Although some of these deals have taken place in Asia – there have been substantial acquisitions in Indonesia, Cambodia and the Philippines – the prime target is Africa. The Land Matrix project identified 358 foreign land deals on the continent covering 15 million hectares – an area bigger than Greece. The number one country for foreign land acquisition is Sudan, where the government has been as welcoming as in neighbouring Ethiopia. Other important countries are Madagascar, Ethiopia, Mozambique and Benin. Tanzania, Sierra Leone and Liberia are not far behind.

These are some of the poorest countries in the world. They all suffer from high levels of malnutrition and food insecurity. They have a history of corruption, conflict and poor governance. Rather than deterring foreign investors, this appears to be one of the attractions. The World Bank study concluded that investors were most likely to pursue land deals in countries with ‘weak land governance’ and ‘poor recognition of local land rights’ – which makes ‘land grab’ sound like an appropriate term after all.

So, who are the foreign investors doing deals in these countries? What motivates them? Perhaps the best way to approach this issue is to position the investors along a spectrum, where the two ends represent different motivations, as well as different sources of capital. At one end are governments of food importing countries worried about security of supply. At the other end are financial investors excited by the profits to be made from high food prices. In between are dozens of different actors who share these two motivations to varying degrees.

Governments of food importing countries in Asia and the Middle East, eager to grow food to ship home, are the engines of many of the land acquisitions. Officials clear a path in target countries by signing memoranda of understanding, agricultural cooperation frameworks or bilateral investment agreements. Political leaders fly in for handshakes and photo opportunities. Governments typically work through private companies to implement deals in foreign countries, but they provide support in the form of equity finance, cheap loans, guarantees or insurance. Cheap money and direct encouragement is enough to convince the private sector to take on projects abroad. This hybrid public-private model is a form of capitalism that is common in much of the developing world. And in many Arab countries it is hard to separate government from the private sector anyway because the same princes and sheikhs dominate both.

Saudi Arabia is one of the most active players in foreign land acquisition. As part of the King Abdullah Initiative for Saudi Agricultural Investment Abroad, the government created an $800 million fund for joint ventures with Saudi companies. Saudi Star is just one of many companies to benefit. Other partners include those firms that had been active in farming at home but now need something else to do because the pumping of domestic aquifers is being phased out. For example, the Hail Agricultural Development Company (HADCO) has begun a pilot project near the Nile in northern Sudan: the general manager explained that ‘the area is big, the people are friendly’ and ‘they gave us the land almost free’. One of the most ambitious new ventures is the Foras International Investment Company, a joint venture involving the Saudi government, private investors and the Islamic Development Bank. Its ‘7x7’ project aims to produce 7 million tonnes of rice on 700,000 hectares over 7 years by investing in Islamic countries such as Senegal, Mali, Sudan and Niger. To handle all these expected food imports, the Saudi government is building a new port at the Red Sea city of Jeddah.

Other Arab states looked at their deplenished larders in 2008 and took similar steps. Tiny Qatar, whose quarter of a million citizens have the highest per capita income in the world thanks to massive natural gas reserves, offered to build a deep-water port at the Tana River Delta in Kenya in exchange for cropland. It established diplomatic relations with Cambodia in 2008 so that it could discuss farming projects. More recently, it has tried to put a private sector face on its activities, using $1 billion from its sovereign wealth fund to create a new agricultural company, Hassad Food. This company has bought 250,000 hectares of prime farmland across Australia and is also looking at acquisitions in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Sudan, Turkey, Cambodia, India, Pakistan and Georgia. By some estimates, Qatar now controls more land abroad than at home.

Almost every oil-rich Arab state has tried to get in on the action. Kuwait and Bahrain have been linked with land deals abroad. An official at the Ministry of Economy of the United Arab Emirates, which includes the emirates of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, spoke candidly in July 2012 about how ‘the UAE has recently acquired and leased more than 1.5 million hectares of land suitable for plantation in Sudan, Eastern Europe and Asia, to maintain the country’s food supplies in the face of progressively rising food prices’. And Libya, even as Colonel Gaddafi berated Western powers for their neo-colonial land grab, dusted off plans to develop a gigantic irrigated rice farm on the Niger River in Mali. In total, countries from the Middle East and North Africa are responsible for around one-sixth of the foreign land deals (by area) in the Land Matrix database.

Among the Asian countries, South Korea has been the boldest. Starting in 2009 the government allocated one-tenth of its agricultural budget to encourage Korean companies to acquire land abroad. ‘Private companies will be in charge of investment,’ a ministry official said, ‘while the government and state-run corporation give technical support.’ By March 2011, 60 companies were operating farms in 16 countries, mostly in eastern Russia, Southeast Asia and Brazil. For example, the world’s largest shipbuilder, Hyundai Heavy Industries, operates a 10,000 hectare farm near Vladivostok in Russia. The government recently changed the metric it uses to assess food security from the ‘self-sufficiency rate’ – the amount of food grown at home – to the ‘independence rate’ – which also includes the amount grown by South Korean companies in other countries. As far as officials are concerned, land acquired abroad might as well be Korean territory when it comes to measuring the security of food supply.

At the other end of the spectrum, far removed from officials worried about food security, investors with purely financial motives have been behind many land deals. The financial crash of 2008 devastated stock markets, bonds, commodity prices and real estate – all the standard asset classes for investment. The one sector that sailed through the crisis was agriculture. Buoyed by strong food prices, and attracting investment after decades of neglect, farm profits and land values rose. Investors wanted a piece of the action. Developing countries seemed to offer extra returns for those with an appetite for risk, as land was so cheap, even free. Investors familiar with the private equity model of buying struggling companies, turning them around and flipping them in a few years could see the parallel; in this case, they could acquire under-utilised land in poor countries, use their capital to introduce ‘modern’ farming techniques, and sell the productive enterprise later on for a big profit.

Pension funds, insurance companies and wealthy families, mostly from North America and Europe, queued up to spin this wheel. They acted through dozens of specialist investment funds. The Wall Street Journal counted forty-five private equity firms looking to raise over $2 billion to invest in African agriculture in 2010, with the largest number based in London. One of the most publicity-hungry was Emergent Asset Management, run by flame-haired Susan Payne, a former Goldman Sachs banker. ‘Africa is the final frontier,’ Payne explained after one investment conference. ‘It’s the one continent that remains relatively unexploited.’ She told investors that investing in farmland in Africa would generate a return of 25 per cent annually – if true, certainly impressive in an era of near zero interest rates.

These investment funds are usually agnostic about whether their farms grow food for the local market or for export – whatever delivers the best price. In fact, in many developing countries it can be more profitable to sell in the domestic market, as tariffs and high transportation costs mean that local prices are higher than what the global commodity houses will pay at the nearest port.

Towards the middle of our spectrum, in between food-importing governments and purely financial investors, are global corporations looking for profit as well as security of supply. Land deals have been negotiated by the established commodity companies, in particular those that specialise in tropical plantation crops such as palm oil, sugar or rubber. These crops can be grown at scale. Considerable investment in processing facilities is needed to turn the raw material into a saleable product. Therefore, commodity corporates with large balance sheets can have an advantage when establishing new areas of production. We have already seen how Olam, Wilmar, Cargill, Glencore and Louis Dreyfus are stepping back along the supply chain, acquiring land and growing commodities. Many others are rushing to do the same thing.

One of the biggest pushes is coming from the large Asian palm oil producers. They are running out of space at home and turning to West Africa for expansion. In the biggest project to date, Malaysian company Sime Darby has allocated $800 million to develop a 200,000 hectare plantation in Liberia. ‘It is increasingly difficult to acquire arable plantation land in Asia and thus it is imperative that new frontiers be sought to meet increasing demand,’ said the company’s chief executive, Ahmad Zubir Murshid. These companies have clear commercial motives but there is also a strategic element to their desire to acquire land. Worried about how to secure supplies in a resource-constrained world, they want to establish integrated supply chains ahead of the competition. Murshid added that one reason for doing the African deal was that Sime Darby would have ‘first mover advantage over future entrants into Liberia in terms of securing choice land’.

Positioned closer to the purely financial end of the spectrum, there is a diverse group of companies that have studied the macro trends around food and believe they can make money by acquiring land in developing countries. We might call them ‘commercial opportunists’. Many are new ventures. Swedish companies such as Black Earth Farming and Alpcot Agro have built up large holdings of land on the fertile soils of Russia and Ukraine. A flurry of biofuels companies emerged in 2005 and 2006 when governments in rich countries imposed mandates on the amount of fuel to be derived from biological material. Armed with ambitious prospectuses, small amounts of money and a few seedlings, these companies acquired concessions all over Africa and Asia, promising to grow vast quantities of jatropha, oil palm or sugar cane. Fifty companies, mostly from Britain, Italy, Germany, France and the USA, launched a hundred projects in more than twenty countries. As we shall see, few fared well.

This group of commercial operators also includes companies from emerging economies who see opportunity in the abundant lands and low yields of poorer countries. Brazilian firms are spreading into neighbouring Paraguay and Bolivia, clearing land and introducing mechanised farming. One of the largest Brazilian agribusinesses, SLC Agrícola, wants to recreate the ‘miracle of the Cerrado’ in lusophone Mozambique by growing soy and cotton. Of all the nationalities, Indian companies are perhaps the most numerous. They have been acquiring plots of land and setting up farming ventures to grow food for local markets and to export to India. East Africa is the main target: it is estimated that eighty Indian companies have invested more than $2 billion in land in Ethiopia alone. Unlike many European and American financiers, who jet in and out of projects and cannot quite give up the comforts of home, Indian entrepreneurs are willing to move to the most remote parts of the world, roll up their sleeves and make a real go of it – although this is still no guarantee of success.

Finally, this spectrum analysis would not be complete without a word on some of the most audacious, but probably least harmful, land grabbers. A few speculators have tried to lay claim to vast areas of land in the hope that they can one day turn their concessions into something valuable. They combine elements of nineteenth-century colonial adventurer, pantomine villain and Walter Mitty. It is not clear if they are exploiters of the poor, or if they are, in fact, being exploited by canny local elites who are happy to take their money and run. Nowhere has attracted them like the world’s newest country, South Sudan, where it is claimed that 9 per cent of the land has been signed over to investment schemes. Few are more colourful than Philippe Heilberg of Jarch Capital.

Heilberg, a former New York commodity trader, first came to attention in 2009 when he announced to the world that he had leased 400,000 hectares of farmland in Unity State in South Sudan. His local business partner was the son of a former warlord, General Paulino Matip. The general was deputy commander of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, the national army in waiting. Although most land acquirers prefer to remain in the shadows, Heilberg sought the limelight, explaining his idiosyncratic business philosophy to the BBC and any journalist that would listen. Rolling Stone magazine ran a feature dubbing him the ‘capitalist of chaos’. ‘This is Africa,’ Heilberg told the magazine. ‘The whole place is like one big mafia. I’m like a mafia head.’ He bragged to Fortune magazine that ‘they can’t change the laws on me, because I’ve got the guns … As long as Gen. Matip is alive, my contract is good.’ However, no one in Jarch Capital had any agricultural experience, and it was never clear how Heilberg intended to develop his massive concession. Both the governor of Unity State and the chairman of the South Sudan Land Commission said they had never heard of the deal. In 2012, following local protests, the President of South Sudan declared that land leases not authorised in the proper manner would be declared null and void. The Jarch project appears to have evaporated in the Sudanese heat. And Philippe Heilberg is no longer giving interviews.

You may have noticed that there is one country that has hardly appeared in this parade of land grabbers. I remember when I first started working on this book I fell into conversation with a man in a London pub. ‘Ah yes, I have heard about these land grabs,’ the citizen said as he put down his pint of ale. ‘China is buying up farms in Africa, buying up the world.’ I have had dozens of similar conversations since. Plenty of public officials seem to share this belief. Everybody knows that China is the world’s chief land grabber, right?

This is where reality diverges the most from hype. Chinese firms have made some land acquisitions related to the commodities they import: soybean farms in Argentina, dairy farms in New Zealand, palm oil and rubber plantations in Southeast Asia. China’s latest strategic plan for agricultural ‘Going Out’, released in early 2012, may herald a more aggressive strategy as it includes plans to create production bases in Brazil, Russia, the Philippines, Argentina and Canada. But China’s activities in Africa have been limited. Although individual Chinese migrants and companies have been running small farms or livestock production units in Africa for many years, the official policy of the Chinese government is not to acquire large tracts of land. Rumours of mega-deals for millions of hectares of land in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique have been shown to be false when investigated. Instead, China has focused on running agricultural research stations to improve the productivity of local farmers – it has eleven training centres in Africa, employing more than 1,000 Chinese agricultural experts. The image of China as a rapacious grabber of African farmland says more about Western perceptions of China, and Western paranoia about China’s economic rise, than it does about China itself.

Speculative deals that evaporate into thin air, Chinese deals that never existed – it is possible to exaggerate the extent of land grabs. Nonetheless, despite these caveats, there are still plenty of land deals out there that are all too real for the local communities affected. From the palaces of Riyadh to the glass towers of Wall Street, from the boardrooms of Mumbai to the trading floors of Singapore, a diverse group of states and companies are making large-scale acquisitions of farmland abroad, mostly in poor developing countries. It is impossible to put an exact figure on it, but there is no doubt that a large amount of land is involved. Overall, the hype is justified. The world has not seen cross-border land acquisition on this scale for at least a hundred years.

The nature of these deals is also different from before. For most of the twentieth century, foreign investment in agriculture in developing countries was confined to specialist cash crops that could only be grown in the tropics – rubber, tea, coffee, sugar, bananas. Even these sorts of investment were in decline since the 1960s, as newly independent states sought more control over their own resources. Now, land acquisition is back in vogue. Multinationals are rediscovering their love for the plantation business. Moreover, most land deals today focus not on tropical cash crops but on producing staple foods such as rice, wheat and maize. This is another feature that we have not seen since the wave of European colonisation in the nineteenth century.

The proponents of large-scale land deals argue that they bring many benefits. The theory is that there are large areas of idle or under-utilised land in developing countries, barely producing any food. Foreign investors can provide the capital, technology, expertise and infrastructure needed to finally bring the agricultural revolutions of the twentieth century to these lands. This will produce more food for local markets, while generating a surplus that can be exported to the rest of the world. It will also create jobs for local communities, tax revenues for cash-strapped governments and better access to markets for small farmers as well. Most of the international organisations that deal with food security – such as the World Bank and FAO – have gone to great lengths to show how these deals, if done properly, can be ‘win-win’, delivering benefits for both foreign investors and target countries. They have invested a lot of time in developing a voluntary code to govern how these investments should be carried out.

However, the way in which many of these land deals have been designed and implemented makes it hard to see how local communities will benefit. As the story of Saudi Star in Gambella illustrates, it is a myth that there are vast areas of ‘idle’ or ‘vacant’ land in the world, suitable for cultivation. It is similar to the concept of terra nullius that past imperialists used to justify their occupation of distant territory, air-brushing indigenous people out of the picture. Almost all fertile land with adequate water is used by someone. It may look empty but this is probably because it is being left fallow as part of a shifting cultivation system, used by pastoralists to graze animals, or, in the case of woodland, used as a source of timber, wild food and medicines. The land may not be utilised to its full potential, compared with high-yield farming systems elsewhere, but it is not unused or unoccupied. When foreign developers take control of large areas of fertile land they are inevitably displacing someone.

Most of the claims to this type of land are undocumented and lie outside formal systems of land tenure. They take the form of customary rights, traditional rules for how communities, families or individuals can use land. These rights are well recognised at a local level even if they are absent from cadastral records in capital cities, where the land may be listed as belonging to the state. Up to 90 per cent of land in Africa is under this sort of customary tenure.

There are fair ways to negotiate the transfer of land between local communities and more powerful foreign investors. Prior consultation, free consent and fair compensation should all be involved. But many of the land deals taking place today do not follow these principles. They are often externally imposed by government officials who ignore customary land rights and make massive transfers at the stroke of a pen, or by local chiefs who have been seduced by the investor’s chequebook and do not have the best interests of their people at heart. Many foreign investors engage in a sort of sham consultation with local people after the deal has been made – they have no intention of changing their plans. Or, in some cases, villagers only learn about land deals when the bulldozers arrive. The amount of compensation paid to local people for the loss of the land is usually minimal. If customary land rights are not recognised, host governments sometimes forcibly evict people without any compensation, calling them illegal ‘squatters’.

The mantra of foreign investors is that it does not matter if local people lose access to the land as they can be employed in the new corporate farming operation. Better a secure, cash-paying job than the precarious existence of the subsistence farmer. This will also help transfer new farming skills to the host country and have lots of spillover benefits for the economy.

Unfortunately, it usually does not work this way. None of the grandiose claims about the creation of jobs have become a reality so far. Many large-scale agricultural projects never get from the planning phase to actual implementation – which makes job creation impossible. The highly mechanised, input-intensive farming system that most foreign investors want to introduce – replicating the norm in the USA or Brazil – is not likely to create much employment even when fully operational. And the few people employed need skills that local farmers usually do not have, which is why so many commercial farming projects in Africa use imported labour from Pakistan, India, South Africa, Zimbabwe or Australia. Local farmers who lose access to land are more likely to find themselves outside the fence looking in, rather than driving a million-dollar tractor and learning to farm like an Iowan. Local shopkeepers do not benefit much either, as foreign investors tend to rely on imported inputs and machinery, rather than spending money in the country.

Land grabs can also cause considerable environmental damage. The clearing of forests for new oil palm plantations in West Africa has led to flooding and soil erosion in surrounding areas. Cambodian farmers downstream from new sugar plantations have found their crops and animals poisoned by chemicals. Industrial farming systems can destroy soil fertility: indeed, because they do not own the land, yet receive huge concession areas, land grabbers are almost encouraged to mine the soil before moving on to a new plot. Perhaps the most contentious issue is water. It has been rightly pointed out that many of the recent deals are more ‘water grabs’ than land grabs. A large number involve drawing water from rivers or lakes for irrigation, or draining wetlands. This can have a negative impact on downstream users. For example, large-scale irrigated rice projects on the Niger River, funded by Libya, China and the USA, aim to triple the amount of water extracted. This will dry and shrink the Niger Delta downstream, a gigantic wetland in the desert that supports hundreds of thousands of fishers, farmers and cattle herders. All food production carries environmental risk but foreign schemes in countries with weak governments are more likely than most to ignore environmental externalities.

Foreign land deals risk undermining the food security of poor rural communities in target countries. Governments and global corporations looking for security of supply intend to export as much of the food as possible – which means that local soil, water and nutrients will be exploited for the benefit of others. Even if the food is sold in local markets, communities displaced by the commercial farms may not be able to afford it. The loss of access to land and water may remove the only livelihood they have, and the economic spillover effects of the commercial farms may be limited. We saw in an earlier chapter how the amount of food produced is only a minor factor in determining whether people go hungry – it has much more to do with access to natural resources, the ability to earn income, and the distribution of wealth and power. Therefore, an approach that only focuses on maximising production may do little to enhance the food security of the poor. In fact, it may do more harm than good. The major World Bank report on the subject concludes that ‘the risks associated with such investments are immense’.

The patent injustice of so many recent land deals has caused a vigorous backlash. The Anuak attack on farm workers in Ethiopia is just the most bloody example. In many developing countries, especially in Africa, land has cultural, sentimental and political meaning. It is a reminder of past dispossession, a symbol of present dignity and a source of future security. The threat of displacement has mobilised peasant groups and local communities to resist. Local opposition has been matched by a campaign by foreign journalists and NGOs to bring attention to this issue. Organisations such as GRAIN, The Oakland Institute, Oxfam, Welthungerhilfe and the International Land Coalition have written reports with attention-grabbing headlines. One journalist described how land grabbing was the ‘hot button issue’ at the World Food Summit hosted by the UN’s FAO in Rome in November 2009. Every time there is an investment conference on the theme of agriculture it attracts a hardy band of protesters, condemning the land grabbers inside. This has been enough to scare many European and American financial institutions away from investing in agriculture in poor countries. The reputational risk is just too high.

Ironically, the campaigners may be doing these investors a favour. This is because many of these land deals are not only unjust; they also do not make economic sense. Local opposition is one reason. It is very difficult to implement a complex project across a large area of land in a remote part of the world if local people are actively opposed. Erecting fences and employing guards is expensive and ineffectual. Things go missing; machines are sabotaged; farmers drive their herds at night through newly planted fields. Physical attacks impede operations: one American farm owner in Ethiopia had to order a medical evacuation when his manager, whom he described as ‘too aggressive in the culture’, was hit on the back of the head with an axe. It is hard to grow food or to make money in that type of hostile environment.

Local opposition can also force host governments, who were once so welcoming to foreign investors, to change course. The determination of the President of South Sudan to cancel speculative land deals has already been noted. The Qatar project in the Tana River Delta in Kenya stalled after local pastoralists and environmental groups fought against it. In Madagascar, news that the Korean firm Daewoo Logistics had signed a deal to lease 1.3 million hectares of the country’s arable land to grow maize and palm oil precipitated a coup that toppled the government. The first act of the new government was to cancel the Daewoo contract (and another deal involving an Indian company). The new minister for agriculture in Tanzania is taking a much harder line on foreign investment in land, stating that under-performing projects will be cancelled and higher rents charged. Foreign investors may think they have protection in the form of contracts and international investment agreements, but paper will not count for much if a regime changes.

There is also a more fundamental economic reason why many of the grandiose farming schemes are doomed to failure. Foreign investors tend to work from the same template. Their plan is to recreate mechanised, ‘modern’ farming systems on large areas of land in the developing world. The claim is that this will deliver ‘economies of scale’. But there are some flaws in this thinking. The ‘modern’ farming systems of the USA, Brazil or Australia have developed in that way for a reason. Namely, capital in these countries is cheap compared to labour, which means that it makes sense to invest in labour-saving technology. Even still, more than 95 per cent of farms in these countries are run by owner-operators – they are still family farms – and average farm size is less than 200 hectares. This is because all the academic research shows that there are few economies of scale in agriculture. In fact, land management has diseconomies of scale. The bigger the area the less a manager can know about microvariations in soil, vegetation and climate across it. A large area also means hiring staff who may not be as motivated as an owner-operator – supervising them is costly. The only economies of scale in agriculture tend to be in acquiring machinery and inputs such as fertilisers and chemicals (bigger operators can negotiate better prices), in obtaining finance and in marketing (more volume equals better bargaining power with buyers).

Conditions are very different in sub-Saharan Africa to the USA or Brazil. Land and labour are plentiful and cheap. Conversely, getting machinery and inputs to remote farms is extremely expensive – and the ability to order in bulk does not greatly lower the cost. Economies of scale may also not count for much when it comes to marketing crops, as the main obstacle is not the ability to negotiate a good price but the cost and feasibility of transport when there are no good roads, railways or navigable rivers. Few investors are big enough – or altruistic enough – to build hundreds of kilometres of roads. The large commercial farming schemes, therefore, seem to have things back to front. Rather than making the most of the local factors of production that are cheap – land and labour – they rely on capital-intensive machinery and inputs that will be costly to deliver. They try to impose a first-world farming system on a social and economic environment that could not be more alien. It is like trying to drive a Ferrari on a mountain track.

One project that is starting to exhibit these economic strains can be found a few miles away from Saudi Star’s property in Ethiopia. It is under the control of a flamboyant Indian businessman named Sai Ramakrishna Karuturi. Six-foot tall and immaculately moustached, he was thrown out of six schools as a boy before gaining an engineering degree from Bangalore University and an MBA in the USA. By 2008 he had overseen an unlikely corporate metamorphosis, turning a family-run cable business in Bangalore, Karuturi Global, into the world’s largest exporter of roses. Some of these roses came from greenhouses in highland Ethiopia.

In April 2008 Karuturi Global was offered a chance to lease a massive 300,000 hectares of land in Gambella to grow crops, for an annual rent of $1.15 per hectare. The company had no experience of arable farming. When Karuturi’s father, who served as chairman, travelled to Gambella to negotiate with officials he concluded that it was too risky to take over a piece of land that was seventy-two kilometres from side to side. But he was over-ridden. ‘Sign it right now,’ his son shouted over the phone from Addis Ababa. ‘I want it signed and sealed before they change their mind.’ To him, it was too good an opportunity to miss. Karuturi boasted that he would soon be the biggest farmer in the world, producing cereals, rice and sugar and generating more than $500 million in profit every year. He brought in farmers from the Punjab, the USA, Uruguay and Australia to help him achieve this vision.

Since then, the project has endured a catalogue of mishaps. Karuturi imported Indian-made tractors to clear the land of trees and scrub, but they were not powerful enough, broke down frequently and had to be replaced by much more expensive American machines – 50 of them at a cost of $1 million each. After much delay, the company planted a maize crop in 2011, but the $15 million crop was washed away by floods. This came as no surprise to local villagers who showed Karuturi the water marks on trees from previous years. ‘We were caught napping,’ he admits. As a result, Dutch engineers were brought in to build a system of dykes and canals. The latest problem is the discovery that the property sits on the migration route of a million antelope, who naturally regard freshly planted crops as an ‘all you can eat’ buffet. The company is erecting a massive solar-powered electric fence to keep them out.

All told, by mid-2012 Karuturi had only prepared 12,000 hectares of land, without harvesting a substantial crop. The company had spent $128 million along the way. This works out at more than $10,000 per hectare, which is more than it would cost to buy an average piece of farmland in the USA. Karuturi is now approaching banks and trying to raise a loan of $250 million to complete the development, but the strains are starting to show. Karuturi Global’s stock price has fallen 60 per cent since it started the Ethiopian farming venture. One visitor to the farm heard a frustrated Karuturi shout at a farm manager: ‘I want crops. I want production. Come to the [Annual General Meeting] and see how investors roast me.’

At the time of writing Karuturi was still in the ring, fighting, but many other project developers have already slinked away in defeat. Most notably, practically every biofuels project launched with such fanfare a few years ago has now collapsed. Three examples from Tanzania tell the same dismal story. A UK venture, Sun Biofuels, folded in 2011 after investing $34 million over five years in a jatropha project. A Dutch firm, Bioshapes, spent almost $10 million on 34,000 hectares of land for jatropha, but only managed to plant 285 hectares before going bust in 2010. A large ethanol project set up by Swedish company SEKAB met a similar fate. The charity Action Aid has identified at least 30 abandoned biofuels projects in 15 African countries. It turned out that jatropha, the supposed wonder crop that would flourish on marginal land, only grew well on fertile soils, with plenty of water and fertiliser. Developers woefully underestimated the amount of work required to clear and plant thousands of hectares, especially where there was local opposition.

All across the world, land deals have stalled or collapsed. World Bank researchers found that farming had only started in 21 per cent of the schemes they investigated. ‘This lag in implementation,’ they found, ‘was normally attributed to unanticipated technical difficulties, reduced profitability, changed market conditions, or tensions with local communities.’ Unfortunately, failed deals still leave a trail of destruction in their wake. Communities have been cleared off their land and promised jobs on new plantations, only to see work stop and investors disappear. Large areas remain leased to foreign companies, which means locals cannot regain possession. If they do occupy the land illegally, this creates even more confusion between formal and customary rights. The land is in limbo. Sometimes, it seems, the only thing worse than a land grab is a failed land grab.

For those who understand the history of large-scale commercial farming ventures in Africa, these developments are not surprising. The last sixty years are replete with similar failures. After the Arab oil embargo of the 1970s, when the USA threatened to withhold food supplies, Saudi Arabia funded the establishment of mechanised farms for sorghum and sesame in central Sudan. Yields were poor, many farms were abandoned, and the forcible displacement of thousands of smallholders helped spark civil war in Sudan in 1983. In the same decade, the Canadian government funded the creation of state wheat farms in Tanzania – nomadic pastoralists now fight with local villagers over who should occupy the long-abandoned farms. The British government’s development agency, the Commonwealth Development Corporation, recently conducted an assessment of its 179 investments in agribusiness over the past 50 years and found that two-thirds failed to produce adequate financial returns. Large-scale farming estates performed the worst.

It is striking how many of the recent land deals involve the acquisition of farms or infrastructure that were part of previous schemes – the Soviet-built dam in Gambella is just one example. Foreign investors are literally picking their way past rusted machinery and weathered signs, relics of past failures, when they arrive on their newly acquired land, full of grand visions. You would think it would give them cause for reflection.

In future, only three types of land deals are likely to survive. The first are smaller, humbler schemes that make a genuine effort to integrate with local farmers and produce real benefits for local communities. Rather than blindly trying to recreate Iowa or Mato Grosso in Africa, they will champion farming systems that make economic sense given local conditions. They will focus more on food staples for domestic markets, which are typically bigger than export markets in any case. And, as we shall see in the next chapter, land may be the least important part of these projects. They will focus just as much on infrastructure, processing and access to markets. There is a role for foreign investment in this, so long as investors are sufficiently patient and have realistic return expectations.

The second type of deal that may survive consists of commercial plantations for tropical commodities such as palm oil or sugar cane. These commodities require significant investment in processing facilities in order to unlock their value for world markets. Production is quite simple and does not suffer from diseconomies of scale like mainstream farming. Demand is growing quickly and at current prices production can be lucrative. These commodities can be grown most profitably in tropical developing countries. However, large-scale plantations that displace local communities, and do not produce real development benefits, will only be able to operate if local opposition is suppressed. Foreign investors can sometimes rely on compliant host governments and local elites to deploy force in this way. This may produce an economic return for investors but it will be ugly. It will not be for investors who genuinely care about corporate responsibility.

Finally, some of the uneconomic large-scale farming projects may survive. There are land grabbers who want to achieve security of supply at any price. They do not care whether the farming system makes economic sense. For example, when Saudi farmers were pumping aquifers dry to grow wheat at home, they received government subsidies worth five times the value of the crop. Therefore, Saudi Arabia may not mind funnelling hundreds of millions of dollars into expensive farming projects abroad. Operating these farms will require the suppression of local dissent. But, again, countries seeking food security for their own citizens may not be unduly sensitive about the rights of local communities in other parts of the world. Governments and parastatal companies with deep pockets and strategic motivations will continue to develop large farming estates in poor corners of the world so long as they are worried about the reliability of global food markets.

If this process continues, we may see the emergence of farming ‘enclaves’, where staff are flown in and out, locals are excluded and the majority of food is exported – with the connivance of local elites. Many oil and mining projects in Africa today are operated in this way, as ‘states within states’ completely separated from the local economy or society. For example, there is an ExxonMobil compound in Equatorial Guinea that has a Texan number as its local dialling code. Saudi investors appear to have a similar vision for their agricultural investments. In April 2012 the chairman of the Jeddah Chamber of Commerce, Saleh Kamel, announced that the Sudanese government had agreed to give up more than 800,000 hectares of farmland so that Saudi Arabia could develop a safe and steady food supply. Khartoum would make the land a free zone that is not subject to any form of taxation or duties and not covered by Sudanese laws. This sounds more like a Saudi colony than a commercial farming investment.

The Saudi Star farm in Gambella, where we began this chapter, is starting to look like a well-guarded enclave already. According to Anuak activists, the Ethiopian authorities responded to the attack on farm workers with a brutal crackdown, killing five local villagers. Ethiopian police and military now provide constant protection to the Saudi farm – one journalist likened it to an ‘armed camp’. Saudi Star executives have taken the killings in their stride. ‘Things are normalised. All our contractors are back to work,’ the chief executive said from the safety of his office in Addis Adaba. There are no plans to change course. Indeed, in April 2012 it was announced that Al Almoudi had leased even more farmland in the northwestern region of Benishangul-Gumuz.

Committed land grabbers are seeing their plans through. The real test will come when the host country of one of these projects suffers an internal food crisis, due to a drought or crop failure. Will people stand by and watch trucks full of grain leave for the ports? Could any government or security apparatus prevent a popular revolt? Kofi Annan has said that it is ‘a terrible business model’ because ‘to believe that if there is hunger at the doorstep the population will let you take [the food] away is itself naïve’. Yet, if there is a global shortage at the same time, what about the needs of the investor country that relies on these exports? Will it agree to forgo the food grown on its land when this is the reason it made the investment in the first place? What sort of pressure or inducements could it apply to local elites? This is a potentially explosive situation.

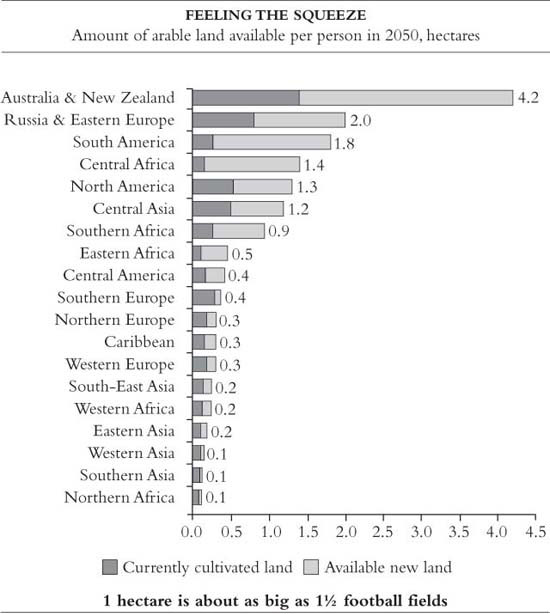

Note: Total available land includes currently cultivated land plus all suitable forested and non-forested land outside protected areas

Source: Land data from IIASA, GAEZ 2009; population data from UN Population Division, World Population Prospects: the 2010 revision