Dangerous trends, nightmare outcomes and the geopolitics of food in the twenty-first century

Earlier in this book we saw that there was no biophysical reason why we could not feed a world of 9 billion people in 2050. Indeed, there is enough food to feed that many today. But just because we can does not mean we will. It depends on how food is distributed and priced, and whether people can access and afford it. So far, as a species, we have spectacularly failed to construct a just global food system – this is why one in eight people go hungry while one in five are overweight. Judging by the way the world responded to the recent crisis, this will not change any time soon. When food inventories ran low and prices spiked, nations and corporations tried to manipulate markets to serve their own interests and scrambled to establish control over food production resources.

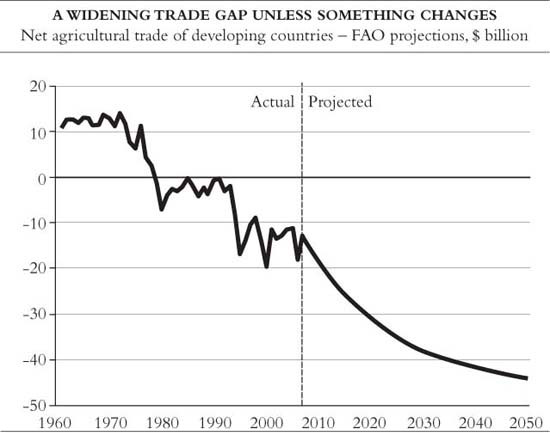

How will these trends play out between now and 2050? Predicting the future is a risky business but I suggest that three things are likely to happen if we continue on the current path. First, the imbalances within the global food system will widen, which will put even more pressure on trade. Second, the way this trade is conducted will be shaped by powerful states, as food becomes a more important geopolitical issue. Third, we are on the verge of an historic wave of agricultural expansion that will draw hitherto isolated parts of the world into the global food economy. This chapter will sketch out the implications of these developments. It will present some scenarios for how the global food system may evolve over the next forty years. Although not inevitable, it is possible to envisage scenarios that produce bleak outcomes for many people.

As we have seen, the biophysical potential of the planet for food production means there should be enough food to go around at a global level. But the picture looks very different from country to country. If we lay down all the trends that affect food security – population growth, ecosystem constraints, climate change, economic development and political systems – it emerges that some regions will be in a good position to feed their people, perhaps even to generate food surpluses. Others will face large food deficits. The gaps between the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ will widen. This will affect the composition of the five ‘food blocs’ outlined in Chapter Two. There will be winners and losers.

The USA and Canada will be among the big winners in the evolving food system. Populations are growing in North America, but there is still a large reserve of fertile land that can be brought into cultivation, and there may still be room to improve crop yields. Although parts of the American West are expected to suffer from reduced rainfall as the climate changes, the prime grain-growing areas will be less affected between now and 2050, and the zone of cultivation should shift northwards as temperatures increase. North America will continue to produce a massive food surplus, as it has for the past 150 years.

Nonetheless, North America’s share of food trade will continue to fall, as the world comes to rely more on other regions as well. The industrialised exporting countries, Australia and New Zealand, are likely to grow their exports as more land is converted to agriculture (for example, in sub-tropical northern Australia), although this will be partly offset by a drying climate. Emerging Asian exporters such as Thailand, Vietnam and Myanmar may struggle to increase production, as there is little new land available for cultivation. The countries of the former Soviet Union, in particular Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Russia, have more potential. They could bring millions of hectares of fertile land into production and double their grain yields. A shrinking and ageing population should, in theory, create greater food surpluses – Russia is expected to have 16 million fewer people by 2050. Climate change could improve growing conditions in the north of the vast Russian land mass. Conversely, climate variability will probably lead to spectacular crop failures as well, so exports will gyrate from year to year.

The region with the greatest potential is undoubtedly South America. It has vast amounts of suitable land in reserve, even without touching the rainforests. Yields are still only half of what is physically attainable given the soils and the climate. The population of this region is expected to grow from 397 million now to 488 million in 2050, which is slow by historical standards. So, there should be plenty of surpluses for the rest of the world. Climate change may cause problems in some areas, for example northeast Brazil, but there are parts of this vast continent, for example Argentina and Uruguay, that may benefit. Most importantly, South America is already on the right trajectory, increasing food production and exports year on year. This shows that it has the social, political and economic capital necessary to realise its biophysical potential. South American countries, and especially Brazil, are best positioned to take advantage of the opportunities created by the new global food economy.

Asia will consume an ever larger share of exports from South America and other breadbaskets. Japan and South Korea will remain major buyers on world markets, although they will see a moderation in food demand as their populations age and decline. But it is the fast-growing Asian economies that will account for most new demand. They are unlikely to return to self-sufficiency any time soon.

The biggest economy is, of course, China. How dependent will it become on food imports? Some alarmists argue that China will eventually face a collapse in internal food production because of falling water tables, soil erosion, pollution and climate change, meaning that the country will have to fling itself on world markets for survival. This is overdone. China faces serious environmental problems but it is taking steps to address them. Climate science does not predict terrible changes for China; indeed, some models indicate that conditions for agriculture could improve. The country still achieves impressive increases in grain production year on year. Above all, demographics are on China’s side: its population is expected to fall by 50 million between now and 2050 and then drop below 1 billion by 2100. China will import more food not because it is starving but because its wealthier population has more expensive tastes.

Instead, the region that we should be worried about is South Asia. This encompasses Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran, Afghanistan and Nepal, as well as the largest country, India. The population of this region is set to explode from 1.7 billion today to 2.4 billion in 2050 – equal to all the people in the world in 1950. India alone will have an extra 450 million people, making it by far the most populous country in the world. There will be 400 million more Indians than Chinese in the world in 40 years’ time.

Almost every environmental indicator for South Asia flashes red. About nine-tenths of all the suitable land is already being cultivated. By 2050 the region will have just 0.07 hectares of arable land per person, the lowest in the world. The crucial wheat-growing Punjab region is threatened by falling water tables and loss of soil fertility. Climate change is expected to scorch the heavily populated plains that stretch from Pakistan to Bangladesh, while disrupting the flow of the Ganges, the Indus and the Brahmaputra, which irrigate millions of hectares of cropland. Rising sea levels will encroach upon the crowded river deltas of Bangladesh. The one bright spot is that crop yields are less than half of what is technically possible, on a par with South America. But people will need to squeeze everything they can out of the land to have any chance of feeding themselves.

Far more likely is that South Asian countries will become major food importers. The consulting firm McKinsey & Company predicts that India will be importing 15 per cent of its grains by 2030 (compared to just 5 per cent for China). The sheer size of India means this will have an enormous impact on global food trade, especially if the failure of a monsoon causes a spike in imports in a particular year. The ripples sent out by China’s recent dabbling in world markets may be as nothing compared to the waves caused by more than 2 billion hungry South Asian consumers.

Just as many populous Asian countries are likely to slide further away from self-sufficiency, other nations that already import food will have to import a lot more. Chief among these are the countries of North Africa and Western Asia, effectively the Arab world. The population of this region is expected to grow by 60 per cent between now and 2050, rising from 450 million to 720 million. There is only 0.10 hectares of arable land per person in this region, and there is little additional land that can be brought into cultivation. Moreover, this is the most water-stressed part of the world. Aquifers are being pumped at unsustainable rates, and there is growing competition for the waters of the Nile, the Tigris and the Euphrates. Climate change will dry out the region even more. The Arab nations make up only 5 per cent of the world’s population, yet they consume more than 20 per cent of the world’s grain exports today. Their massive food deficit is set to widen.

Where will the European Union fit into this evolving food system? The answer is not straightforward. Much of its good land is already being used, yields in core member states are already close to the maximum, and biofuels could swallow up more crops in the future. On the other hand, climate change impacts in the next forty years will be limited (outside the Mediterranean countries), new member states such as Poland and Romania have untapped agricultural potential, and a shrinking population should lead to more food surpluses. Higher food prices could encourage renewed investment in farming, while changes to subsidies – away from payments for holding land – could create stronger incentives for production. As a result, the European Union has some choice about its food future. Nevertheless, it is probably safest to assume that its position in the global food system will not change greatly – it will continue to export small amounts of wheat, meat, dairy and luxury foods, while sucking in large shipments of grains, oilseeds and other raw commodities.

And what of sub-Saharan Africa? Its fate is the hardest to predict because the trends shaping global food production will pull the region in different directions. On the one hand, sub-Saharan Africa will undergo extraordinary population growth. The number of people will more than double, from 878 million today to almost 2 billion in 2050. Most of this growth is locked in because of the huge number of young people already in these societies. Many African countries are beset by environmental challenges such as soil degradation, desertification, deforestation, water scarcity and recurring droughts. The region is expected to be one of the worst hit by climate change: for example, one study predicts that agricultural productivity in Southern Africa could fall by one-third between now and 2050. Alongside the environmental problems, many African countries have poor infrastructure, weak states and unproductive farming sectors. Sub-Saharan Africa is Ground Zero for many of the food production challenges discussed in this book.

On the other hand, sub-Saharan Africa has enormous potential to increase its food production. It vies with South America as the land bank for the world. In theory, it has more than 750 million hectares of suitable land that could be brought into cultivation, which is almost half all the arable land in use today globally. In Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia, for instance, less than one-eighth of the potential farmland is actually cultivated. This means that the amount of arable land per person could be maintained even as the population doubles. Moreover, the ‘yield gap’ on cultivated land – the difference between what farmers actually grow and what they could grow using better techniques – is the highest in the world. African farmers could double or triple their yields and still be well below the theoretical maximum.

Sub-Saharan Africa is, therefore, a conundrum. If its agricultural sector does not improve, the region could suffer under the twin scourges of population growth and environmental change and become a massive net importer of food. Alternatively, if sub-Saharan Africa uses its natural resources to the full potential, it could not only satisfy its own needs but could become a breadbasket for the rest of the world. How this conundrum is resolved will be a major factor in determining the shape of the global food system in the twenty-first century.

Irrespective of how Africa develops, one thing is clear. The imbalances in the global food system are set to grow. There will be an ever greater divergence between where food is grown and where it is needed. As a result, there will be greater pressure on trade to fill the gap. How will this trade be conducted? Through open markets and global cooperation? Unfortunately, the evidence provided by the response to the recent food crisis points in a different direction. Trapped in a Prisoner’s Dilemma, food producers imposed taxes, quotas and bans on exports in an attempt to reduce domestic prices, while food importers hoarded food and panic purchased at almost any price. Private markets malfunctioned, as financial speculators magnified volatility and made it harder to manage risk. Canny commodity traders profited handsomely from the turmoil. The response of states and corporations was to try to establish captive supply chains, bypassing normal markets. They went all the way upstream in an effort to claim the ultimate means of production – land and water. The food crisis sparked a scramble for resources, the likes of which have not been seen for a hundred years.

One thing is clear from this response: food importing nations no longer trust open markets to provide. This is hardly surprising. Trade in food has never been free. Even the neo-liberal project of the 1980s only succeeded in reducing the food trade barriers of weaker developing countries. It barely dented the subsidies of Europe or North America, and never succeeded in convincing China or India to open their markets to a global free for all. The turmoil of recent years, and the shift from an era of abundance to one of relative scarcity, has only reaffirmed the belief of governments that food security is too important to be left to the market.

The Greek philosopher Socrates said that ‘no man qualifies as a statesman who is entirely ignorant of the problem of wheat’. This will be truer than ever during the twenty-first century. We are at the beginning of a period when there will be intense competition over who has access to food and how the profits from it are shared. Food is set to become a much more important geopolitical issue. Those countries that produce agricultural surpluses will gain additional leverage. For countries that cannot produce enough to feed their people, food security will become a key driver for foreign policy. Some will have the wealth or power to secure what they need, while others could find themselves in a precarious position.

One country that stands to benefit is the USA, as it will continue to be the world’s biggest food exporter for many years to come. In the past, control over food was an important diplomatic and military weapon for Washington. In both the First and Second World Wars, the USA denied supplies to its enemies and diverted food to its Allies on preferential terms. Commodity trading firms were forced to act under the instruction of the US government as the international grain trade became a ‘public utility’. During the Cold War, Washington used subsidies to supply client states with cheap food, turning off the tap when unfriendly regimes came into power. When prices spiked during the early 1970s, American officials tried to extract political advantage by negotiating grain deals with the governments of the USSR, Poland and Japan. In 1980 President Carter withheld 15 million tonnes of American grain from the Soviet Union in retaliation for the invasion of Afghanistan.

More recently, this sort of food diplomacy has gone out of fashion. Washington made no attempt to control food exports when prices spiked in 2008 or 2012. The USA also shied away from using food as a weapon against its enemies. For example, the USA continues to sell food to Iran despite imposing wide-ranging sanctions on the country because of its nuclear programme. The value of total American exports to Iran actually rose by one-third from 2011 to 2012, chiefly because of grain sales. Lobbying by farmers and commodity traders (such as Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland) has helped keep every market open to American food.

Yet, in the event of war or serious crisis, control over a large proportion of the world’s food exports will be a powerful weapon. It is bound to play a role in the country’s complex relationship with China. In 2011, for the first time, China became the biggest single importer of American agricultural products. China spent $20 billion on imports from the USA that year. Soybeans are now the USA’s second-biggest export to China, topping aircraft, cars and semiconductors. The American agricultural system, like its military strategy, is pivoting towards Asia.

A concrete manifestation can be seen at the Port of Longview in the Pacific Northwest, where huge silos have gone up as part of a $210 million grain export terminal, the first such facility to be built in the country for 25 years. Traditionally, US food surpluses were barged down the Mississippi River to ports on the Gulf of Mexico. Now, the growing volume of soybeans and maize destined for China is driving a reconfiguration of the transportation system. Billions of dollars are being invested in transcontinental railroads so that 100-car trains can take harvests directly from the Midwest to the Pacific coast.

Agriculture is one of the few bright spots in the USA’s lopsided economic relationship with Beijing, helping to balance out a yawning trade deficit in manufactured goods. In the event of a political crisis, for example over Taiwan, American control of a large proportion of China’s food imports could provide leverage. However, it will also create co-dependence, further enmeshing the two countries in each other’s economies. Chinese consumers need American agricultural products, but American farmers also need the Chinese market and will be reluctant to give it up.

An era of relative scarcity should give emerging food exporters such as Brazil, Argentina, Russia and Ukraine a stronger hand in global affairs. The challenge for these countries will be reconciling competing domestic interests. Farmers and the rural economy will benefit from higher food prices and strong export demand. But consumers and the urban economy may suffer as domestic prices go up. Because households in many of these countries still spend a substantial share of their income on food, there will be calls for export restrictions, so that more of the agricultural surplus stays at home.

The outcome of this struggle will be determined by the relative influence of urban and rural lobbies. In Argentina, for example, the populist Kirchner government, which draws most of its support from the urban working class, is pursuing cheap food policies at the expense of farmers, imposing crippling export controls on beef and grains. Brazil, by contrast, where the agriculture sector has more political clout, has refrained from restricting exports. Availability on international markets, therefore, will sometimes depend on the domestic politics of food.

Food importing nations will seek to reduce these political risks by diversifying their sources of supply. The Chinese government is aware of the dangers of becoming too dependent on American food. It is therefore forging strategic relationships with a wide range of food exporters by signing trade agreements, providing low-cost loans, investing in local companies and agreeing currency swaps (so as to help position the Renminbi as a currency of international trade). This ‘Going Out’ strategy is part of a global Chinese effort to secure natural resources, not least in the energy and mining sectors.

One of the most interesting Chinese initiatives came to light at the end of 2012. Since 2008 China has offered a series of massive commodity-backed loans to countries in South America and Africa. They receive billions of dollars of infrastructure finance, while guaranteeing repayment in the form of raw materials, usually oil. In 2012 China extended this model to food. The Export-Import Bank of China agreed a $3 billion loan-for-crops deal with the government of Ukraine. Under this arrangement, Ukraine will receive much-needed finance to purchase agricultural technologies and inputs, and, in return, China will receive 3 million tonnes of Ukrainian maize each year. China is not trying to get food on the cheap – the value of the maize will be set according to prevailing market prices. Instead, China’s goal is to secure a reliable line of supply outside of normal market channels.

Other wealthy food importers – such as Japan, South Korea, India and the oil-rich Arab states – will continue their efforts to secure supplies, whether by constructing integrated supply chains or going all the way upstream and acquiring land. Although this activity will be largely carried out by private companies, it will be encouraged and sometimes financed by governments as part of national food security policies. In this form of state capitalism, the lines between public and private will remain blurred.

We are likely to see more food alliances between importers and exporters. Just as oil dependency defined international relationships in the twentieth century, food trade will bind countries together in this century. The importance of these relationships will become clear in times of crisis. During the recent food crisis, countries that imposed export restrictions often made exceptions for allies or client states. For example, India exempted Bangladesh and Bhutan from its rice export ban, allowing stocks to flow at below the prevailing market price. Food importers will look to establish privileged relationships with suppliers so that they get first call during times of scarcity. Government to government deals will be common.

If food production is tied up in captive supply chains, long-term contracts and government to government deals, there will be less food available for open exchange. Global food markets may become thinner and more residual. When we add to this the other factors explored in this book – more extreme weather, less elastic demand, the coupling of food and energy prices, uncontrolled financial speculation – the result can only be extra volatility on international food markets. More frequent and more extreme price shocks will become the norm.

The losers in this scenario will be poor countries that lack the natural resources to feed their growing populations and do not have the wealth or political influence to secure supplies from abroad. They will have to make do with the crumbs that fall from the top table. According to FAO projections, under a business as usual scenario net imports of cereals by developing countries will more than double from 135 million tonnes in 2008/09 to 300 million tonnes by 2050. These countries will be highly exposed to international price shocks. A sudden rise in food prices will place a huge strain on their balance of payments, especially as it is likely to be accompanied by a simultaneous rise in energy prices. It will cripple the spending power of households that already allocate most of their income to food. Ultimately, price spikes will lead to more hunger, illness and premature death among the poorest sections of society unless safety nets are in place.

Higher food prices will also lead to conflict. In a recent report on ‘Food Prices and Political Instability’, two researchers from the International Monetary Fund provided empirical proof for something that most people intuitively knew. After studying the impact of variations in international food prices on 120 countries between 1970 and 2007, they found that increases in food prices in poor countries led to ‘a significant deterioration of democratic institutions’ and ‘a significant increase in the incidence of anti-government demonstrations, riots, and civil conflict’. Or, as Bob Marley put it in one of his songs, ‘A hungry mob is an angry mob.’

This instability is unlikely to stay within national borders. Hungry mobs tend to move to where food is available. This is already playing out in the West African Sahel, a belt of semi-arid land along the southern edge of the Sahara Desert. For decades the region has suffered from drought, soil degradation and rapid population growth. Many people have moved south, seeking land in better-watered areas. Since the late 1960s, 5 million people from Burkina Faso and Mali have migrated to neighbouring Côte d’Ivoire. The country fell into civil war in 2002, largely because of the uneasy relations between immigrants and local people and the growing shortage of land. This may be a sign of things to come. The Stern Report commissioned by the UK Treasury estimated that by the middle of the century 200 million people could be permanently displaced ‘climate migrants’.

Military strategists and intelligence analysts take these threats seriously. A few years ago, the US National Intelligence Council, the body that provides long-range strategic analysis for the American intelligence community, issued a much-quoted report called ‘Global Trends 2025’. It identifies food security as a major strategic issue in the coming decades. It describes how 21 countries, with a combined population of about 600 million, are already suffering from cropland or freshwater scarcity, and how 36 countries, with about 1.4 billion people, are projected to fall into this category by 2025. Most of these countries can be found within an ‘arc of instability’ stretching from sub-Saharan Africa through North Africa, into the Middle East, the Balkans, the Caucasus, and South and Central Asia, and parts of Southeast Asia. These are countries with fast-growing populations, where most people are below the age of eighteen years. They are the countries most susceptible to conflict. A food price shock is the sort of spark that could set them alight. The blowback will be felt all around the world.

The ‘arc of instability’ drawn by the US National Intelligence Council includes countries that have abundant resources of land and water but are not using them to their full potential. Most are found in sub-Saharan Africa. In so far as they rely on food imports, they are vulnerable to the same price shocks as other countries that are not blessed with such natural endowments. Yet, they are also subject to another risk – exploitation, even colonialisation, by outsiders.

As we have seen, there is no biophysical reason why we cannot meet the growing demand for food between now and 2050. But it cannot be done only by relying on the advanced agricultural systems of North America, Europe or Asia alone. Instead, new land will have to be brought into production. Yield gaps will have to be closed. The regions with the greatest potential for increased production are South America and sub-Saharan Africa. They contain large areas of fertile lands that are sparsely populated and uncultivated, or cultivated with rudimentary techniques and oriented towards subsistence production for local communities. Now, the pressure is on to change how these lands are managed and to integrate them in the global food economy.

Throughout history, there have been periods of rapid change when territories have been brought under new agricultural systems and pulled into more powerful regional or global food economies. Change usually happened at the point of a sword and at the expense of indigenous peoples. The Roman Empire imposed its Mediterranean systems of grains, vineyards and animals on the tribes of Northwest Europe – Roman soldiers received land in return for their victories. The Chinese carried the legendary Five Grains from present-day Vietnam in the south to Korea in the north, building the world’s most durable empire in between. In medieval Europe, Teutonic Knights from Germany conquered Slavic tribes to the east who still practised ‘slash and burn’ cultivation. They introduced a more productive farming system and created a vast cereal-growing region, served by rivers flowing into the Baltic Sea, which eventually became Prussia.

From the sixteenth century, Europeans brought wheat and livestock to the Americas, Africa, Australia and New Zealand, ‘taming’ the temperate grasslands. The opening up of the Argentinian Pampas only happened in the 1870s and 1880s and it entailed the killing or expulsion of large numbers of indigenous people. Settlers from Tsarist Russia brought new farming systems to Siberia, shuttling food back to St Petersburg on the Trans-Siberian Railway. In the late nineteenth century, French colonialists invested heavily in irrigation infrastructure in the thinly populated Mekong Delta in Vietnam, bringing farmers down from the north and laying the foundations for what is now one of the world’s most important rice bowls. Soon after, when Japan found that domestic agriculture could no longer support an industrialising economy, it colonised Taiwan and Korea, turning them into rice and sugar producers for the home market.

All these agricultural expansions shared certain features. Societies with advanced farming systems that hit up against ecological limits at home conquered and colonised fertile lands that were seen as under-utilised. In almost all cases, these lands were already occupied. But the native farming systems were less productive, and their civilisations were weaker. Indigenous people were displaced, assimilated or exterminated. This process usually involved a transition from traditional communal property systems to individual private property rights – the enclosure of common lands. At the end of the process, much of this land was concentrated in the hands of the conquerors or of complicit native elites who had adapted to the new realities. And production was geared towards the export of commodities back to the imperial metropolis or into a globalised capitalist economy. Agricultural innovation spread around the world, but at massive human cost.

Thankfully, by the second half of the twentieth century, change usually happened in a different way. Innovations spread through cooperation rather than conquest. The ‘Green Revolution’ was promoted by charities such as the Rockefeller Foundation and by UN agencies, funded by rich-world governments. It was embraced by Asian countries that were experiencing rapid population growth – such as India and China – and rolled out without loss of sovereignty or foreign exploitation.

One reason for the peaceful spread of new farming systems was that the modern agricultural revolution relieved the pressure on land. For most of history, the main way to boost food supplies was to increase the amount of land under cultivation: when the global population multiplied five-fold between 1700 and 1961, the amount of cropland in the world also grew by five times. But in the next three decades, world population rose by 80 per cent but cropland only increased by 8 per cent. Instead, increased production came from higher yields. Rather than expanding the agricultural frontier, everyone focused on using the land within the frontier, and within their own borders, more productively.

Moreover, powerful countries such as the USA that possessed the new agricultural knowledge had large food surpluses. They did not need to force their more productive systems on less developed regions to feed people at home. If other countries chose to adopt these methods, so be it. But for those poorer countries that failed to do so, there was weak external pressure to change. People in these countries could just about survive on the cheap imports and food aid that was a by-product of global surpluses. The massive gap in productivity that had opened up between the most and least productive farmers could persist.

However, now that the world food system is characterised by scarcity, the gap in productivity has created a dangerous vacuum. Powerful countries with access to capital and agricultural technology are hitting the ecological limits of domestic food production. They look around the world and see land that is not being fully utilised by poorer, weaker states. All the science indicates that some of these less productive areas will have to close the yield gap and expand the area under cultivation, if there is to be enough food to go around. There are plenty of foreign states and investors willing to undertake this task if local governments are unable to take the necessary steps. Under-developed, resource-rich countries are being presented with an implicit ultimatum: ‘use it or lose it’.

South America looks like it will be able to keep control of its agricultural development process. It is achieving impressive increases in food production year on year. It contains relatively strong states that can withstand outside pressures. Indeed, in the last two years Brazil and Argentina have introduced restrictions on foreign ownership of farmland, following a rush of reported land deals. They still welcome foreign investment but only if local partners keep control.

In contrast, most sub-Saharan African countries have much weaker state institutions. They are starting from a much less developed position in terms of infrastructure, education and wealth. Agricultural productivity has failed to keep up with population growth over the last three decades, even though many countries possess enviable amounts of fertile land and freshwater. For example, the World Bank talks about the African Guinea Savannah, a 1.5-million-square-mile band stretching across the middle of the continent, as containing ‘the world’s last large reserves of underused land’. Africa is where outside pressures to expand the agricultural frontier, and to integrate land into the global food economy, will be most intense. The recent ‘land grabs’ in Africa are the first manifestations.

There are some uncomfortable echoes from the colonial past in these land deals. Many involve the conversion of communal or public lands into private property. In his book The Landgrabbers, Fred Pearce warns that ‘we could be witnessing the beginning of the final enclosure of the world’s unfenced lands’. Large estates are being created and land ownership concentrated. Local people are being displaced to more marginal land or expected to work as wage labourers. The food grown on the land is destined for cash markets, rather than local subsistence. This fits the pattern of previous agricultural expansions that were marked by exploitation and loss of sovereignty.

The fact that private companies are in charge of most of these deals is not inconsistent with colonial precedence. From the sixteenth century onwards, chartered companies were used to spearhead European expansion into North America, the Caribbean, India and Africa. The British East India Company is the best example, practically carving out an empire in South Asia before handing it over to Queen Victoria. When the millionaire imperialist Cecil Rhodes seized East Africa in the late nineteenth century, he ruled through the British South Africa Company, which was given a Royal Charter by the British crown. The colourful cast of land speculators and dreamers that Rhodes attracted to Africa are not unlike some of the entrepreneurial individuals that we encountered in the previous chapter. It was imperialism on the cheap, ‘informal if possible, formal if necessary’. Governments only intervened when the companies got themselves in trouble and required military protection, or when their exploitation of the natives became too offensive. The flag followed trade, rather than the other way around.

Finally, colonial powers have always acted through local elites. How else could a few hundred British administrators control a territory the size of India? All the recent land deals in Africa have been sanctioned by local officials or chiefs at some level. Many genuinely believe that foreign investment will benefit their people, but others may stand to gain personally. Once investments are made, there are subtle ways that foreign powers can maintain influence over local elites. Powerful individuals can be invited into corporate ventures as business partners, thus earning a financial reward from farming projects. Supportive governments can be propped up by cheap loans and arms sales. So long as the general populace do not have an effective check on their leaders (such as democracy), exploitative situations that benefit foreign countries or companies can continue for long periods – as the longevity of many African dictators amply demonstrates.

For all these reasons, there is a risk that land deals result in the exploitation of poor countries through a form of neo-colonialism. One advocacy group, Food First, warns that we may see the emergence of ‘cereal republics’, just like the ‘banana republics’ that developed in Central America a hundred years ago under the influence of US food corporations.

If we want to get an idea of where this could lead – a true nightmare scenario – then we could do worse than look at one of the most painful passages in the history of my homeland. In the sixteenth century, Ireland was a heavily forested island whose mostly Gaelic population subsisted on cattle husbandry and rudimentary arable farming. The full British conquest of Ireland, which started with Henry VIII and ended with the brutal Cromwell campaign, was accompanied by the confiscation of native lands and their transfer to thousands of English and Scottish settlers. These new settlers, backed by London finance, built roads, cleared forests and introduced more intensive farming systems. Ireland was dragged into the market economy of the British Empire. By the early nineteenth century Irish farming had split in two. There was an export sector, occupying the best land, which produced wheat, meat, butter and eggs for Britain at a time of rapid industrialisation. Ireland was the source of three-quarters of its neighbour’s food imports in the early 1800s. Meanwhile, the marginalised Catholic masses rented tiny plots on poor quality land and subsisted on a diet of potatoes.

When potato blight struck in 1845, the country’s food staple rotted away. Starvation quickly followed. But there was no interruption to the export of food. Two-fifths of the Irish wheat crop was sent abroad on the eve of the famine. Half a million pigs were shipped across the Irish Sea in one year. Total Irish food exports in 1842 could have fed two million people. It was not that food was unavailable but that the majority of people were too poor to afford it. They could not compete with richer British consumers. And Irish commercial farmers, both Catholic and Protestant, were not prepared to forgo this market for the sake of charity. It is thought that 1 million Irish people died during the Great Famine and that a similar number were forced to emigrate. This is a graphic case study of how unequal land ownership, powerful economic incentives and complicit local elites can create a situation where foreign interests are served while local people starve.

The Irish experience in the mid-nineteenth century is a nightmare scenario, one that Africa must avoid at all costs. Yet, there is as much opportunity as threat in the current situation. The corollary of the pressure being exerted on African countries to grow more food is that these countries have the natural resources to be able to generate wealth for themselves. If they set themselves on the right development path, they can achieve food security, export agricultural surpluses, and get rich in the process. As Kofi Annan says, ‘Africa has an opportunity not only to feed itself, but to feed the world.’ How can this opportunity be grasped? How can we avoid the bleak outcomes sketched out in this chapter? It is time to stop speculating about what could go wrong and instead think about what should be done.

Source: N. Alexandratos & J. Bruinsma, World agriculture towards 2030/2050: the 2012 revision, FAO, 2012