Day 2

Monday, November 8, 1920

In Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise, just past midnight, Brigadier General Wyatt climbs down from a military car. He is the director of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the man charged with organizing the burial of the dead of the British Army. Beside him is his deputy, Colonel Gell. The men walk toward two soldiers standing guard in front of a makeshift hut. The more senior of the soldiers steps forward and salutes. “They’re ready for you, sir.”

“And have the selection parties gone?”

“Yes, sir, they have.”

“And their arrivals were staggered as ordered?”

“Yes, sir, they were.”

“Very good.” Wyatt steps around the man and through the corrugated metal doorway. Beyond a small paraffin lamp, barely visible in the dim light, lie four stretchers. He stands, listening to the wind as it lifts and whistles through the sides of the hut. To his left, standing open and empty, its lid beside it on the ground, is the shell of a plain wooden coffin. On the stretchers before him are four shapes, each of them covered with a Union flag.

They are very small bundles. These cannot be bodies. These are just scraps of things; they look like little more than rags.

He is seized with the sense that something has gone terribly wrong.

But then he shakes his head. Of course they are not bodies. They have been in the ground for far too long for that.

He thinks of what has brought him to this spot, barely three weeks since the Cabinet’s decision to go ahead: of the flurry of telegrams; the brief, rushed meetings of the emergency selection committee; the work it took to persuade a reluctant king that this might be a good idea.

He hopes it is. He very much hopes that they have judged the country right, and that, in four days’ time, this will be seen to have been worth it, after all.

Outside, he hears one of the soldiers cough.

Wyatt gazes out over the stretchers as though to fix this moment in his mind. Then he closes his eyes and, very briefly, reaches out, touching his hand to one of the stretchers. He knocks on the wall of the hut, and the colonel steps inside. Without speaking, Wyatt indicates the stretcher he has touched. The two men lift the bundle, still wrapped in its sack, each end tied up with string, and lower it into the waiting coffin. They screw the lid in place and cover it with its tattered flag. Then they leave, climbing back into their regimental car, which backfires once, twice, into the night, and drive away.

In the early hours, while the sky is still dark, two more men approach the hut. They exchange salutes, and the guards stand aside.

The men see the closed coffin with the tattered flag draped across. They pause for a moment before it, and then move to the other stretchers, the three that were not picked. They lift the first and load it into the ambulance. Then they come for the second stretcher. Then the third.

A chaplain, roused from sleep, an army greatcoat thrown hastily over his robes, joins the men in the front of the ambulance. They drive south along the road leading to Albert. When they have been driving for twenty minutes or so they stop. By the side of the road is a large shell hole. The men came past here, earlier in the day, and marked the place.

They light a storm lamp and place it on the ground, where its flame illuminates a medium-sized hole, about ten feet wide. A sharp wind cuts across their faces. They are eager to be back inside, in bed. They slide the first sack into the hole. It hardly makes a sound as it falls. When all of the sacks are lying in the earth the chaplain climbs down from the vehicle. He stands beside the shell hole with his leather-covered Bible in his hand. The shapes of the sacks are just visible at the bottom of the pit. Standing at the lip of the hole, the wind whipping his hair across his forehead, he says a short prayer. When he has finished, the soldiers take up their shovels and hastily cover the bodies with earth. Then the three men climb back into the ambulance and drive away.

Ada rises and dresses quickly, going over to the window and pulling the curtains wide. The street below is quiet, the sky brightening. It is early, and though Jack has left already, some of the last men are still making their way to work. The light of morning fills the room, finding familiar things to fall on, lifting the shadows of the night before.

She has hardly slept. All yesterday evening, she and Jack circled each other, and it seemed to her as though that boy were there still, in the room between them, as well as their son, Michael, his name echoing in the space, the first time it has been spoken in more than three years.

But there is something about standing here, in this ordinary light.

Perhaps she heard the boy wrong. Perhaps she heard only what she wanted to. It wouldn’t be the first time.

Whatever the explanation, from the way he left, the boy isn’t likely to come back.

She turns to the dresser, where there’s a photograph of her and Jack, taken twenty-five years ago today. The pair of them are staring straight at the camera and laughing. She picks it up and brings it closer. It had been her idea to have it taken. In giddy spirits, straight after the ceremony, she’d dragged him into the studio on the High Road, where a fussy young man showed them into his back room and held things up for them to look at: a stuffed teddy, a feather duster, a bicycle horn. When he honked it they laughed out loud, as the camera exploded in a burst of light.

They look so young. She brushes the top of the dresser lightly with her sleeve and puts the photograph back. She remembers how she felt, walking up this street for the first time, toward their house: the future unrolling before them, waiting to be stepped into, sunlit, wide.

Twenty-five years of marriage. Of learning to live with someone. Learning to love them. Learning to bury the things they cannot bear to face.

It is Monday, and so, as she does every Monday, she strips the bed down. But today, before lifting the sheets, she stops, caught again by memory. They would spend whole mornings here, Sundays, when they should have been in church, his fingers twined in her hair, their legs wrapped around each other, speaking low. She gave birth in this bed, with a midwife from the next street. The shock of it. The astonishing, red-bawling jubilance of her son.

She turns, catching herself in the mirror. The sideways light from the window is not kind. What does he think, her husband, when he looks at her now? She puts her hands to her face, pulling it so that the heavy skin around her jaw tightens, briefly, before she allows it to fall.

What is wrong with her today? It is the anniversary, making her remember, keeping her from her work. She bundles the laundry into her arms and goes downstairs, filling the buckets at the pump in the yard, putting the sheets into the copper to boil. She makes up the starch, stirring it first with cold water, then hot, then rinsing the sheets, and turning them through the mangle. It’s hard work, and as she turns the handle, another sudden memory assails her: her son, as a small boy, standing beside her, helping her, holding the sheets as straight as he can, while she turns the roller, feeding the sodden cotton through.

Michael.

It winds her, this memory.

After a moment, forcing herself to breathe again, she pushes it away.

The queue is a long one this morning. Evelyn can see it as she passes the entrance to the Underground, all the way around the corner and halfway down the street. She needs to cut through the line to reach the back door of the office, so she pulls the brim of her hat down and lifts up the collar of her coat. “Excuse me.”

A fair-haired man makes room to let her through, and she squeezes past him, shoulders hunched. She’s relieved when she reaches the office door; sometimes some of the repeat visitors see her, and it doesn’t do to be recognized in the street. She takes off her hat and coat and hangs them in the hall, then goes through to the cramped little kitchen. Despite the chill of the day, she opens the sticky window that gives out onto the courtyard at the back. For a moment, in the quiet, she thinks she must be the first one in, until she hears the door from the office open and Robin moving down the corridor toward her.

“Good morning.” She turns to see Robin standing in the doorway, his broad frame encased in a tweed jacket and trousers, smiling, as though he knows something pleasant about what today might have in store.

Irritating. Immediately irritating.

“Good morning.” She makes her voice as neutral as she can. There’s little point making much of an effort. He is still quite new—has only been here a week or so. There have been many Robins. They come for a month, for two; sometimes, the sturdy ones, for as many as six, armed with their smiles and their good intentions, and then, after a month or two, they leave, defeated by the monotony, the misery, and the men. One of them lasted only a day, a small, red-faced man who’d been a teacher before the war. Someone had made him cry. As he was leaving, he turned at the door and told her she was a fool, that this was worse than being in France.

Robin picks up the battered kettle and leans over the sink to fill it. “Nice day,” he says, nodding appreciatively at the open window. “Good and crisp.”

“I’m not sure that you have enough time for that.”

He looks surprised. “I suppose not.” He puts the kettle down on the other side of the sink. “How are you this morning?”

He looks so fresh and rested. So friendly. He actually seems as though he’d like to know.

“Fine,” she says. “I’m absolutely fine.” She leaves him standing by the window, picks up her satchel, and makes her way into the small office, where the hunched shapes of the waiting men are visible outside. The first few in the queue are slumped on the ground, asleep most probably; they will have been there for hours. When she switches on the light those who are sitting on the ground haul themselves to their feet amid a general pushing and jostling about. She can hear their muffled expletives through the glass.

As Robin enters the room behind her, she checks she has everything she needs for the morning’s work: pens and enough of each of the differently colored forms that she must fill in for each case, each comment, each complaint. Pink for officers, green for the other ranks. Then she looks at her watch. Three minutes to nine. She takes her bundle of keys from the top drawer of her desk and goes over to the door.

“Early,” says Robin.

“Yes, well.” She turns back to him. “Are you ready, or not?”

He maneuvers his tall frame around his desk, and when he’s settled in his seat, salutes her. “Ready or not.”

She rolls her eyes and opens the door.

There’s a surge from the back, and some of the sleep-dazed men at the front topple, before regaining their balance. Evelyn steps out into the chill morning air. “Any men caught making a nuisance will be asked to leave or go to the back of the queue. Is that understood?”

A bit of heckling rumbles from farther down the line.

“Is that understood?”

The heckling quiets. A few sheepish Yes, misses float toward her. Evelyn goes back to her desk, feeling the familiar tug of concern for this shabby bunch of men. But compassion is a swamp. It’s better not to get stuck in it. Especially not at nine on a Monday morning. She’d never get through the week.

As her first man makes his way over toward her desk she gives him a swift look. Amputee. From the way his right trouser leg is pinned it looks as if it has been taken off all the way to the hip. There’s no false leg; the stump was probably too small to fit against. He takes his place on the seat before her. It’s a game with her, to guess a man’s rank before he speaks. In this post-khaki world, the extremes at either end of the scale are easy to spot, and have remained, so far as she can see, as rigid as they ever were, but the middle ground is different; it has not yet settled. The temporary gentlemen are the trickiest: those who were promoted from the ranks for their service in the field and are now stuck between society’s strata. Temporary gentlemen: such a mean-spirited little phrase; still, it just about sums it up. This one, she is sure, is no gentleman, temporary or otherwise; from his dress and bearing, he is a private through and through.

She dips her head and takes out the first of her forms.

When her fourth man approaches the desk, she knows that he’s trouble without looking twice. “You ready for me now, then?” he says, sitting down before her.

There’s something about him, a confidence, a posture. Officer? His accent is indeterminate. She lines up the form against the side of her desk. Rank? Difficult to say; she can’t call this one.

“Name?”

“Reginald Yates.”

“Rank?”

“Second lieutenant, as was.”

She writes “Reginald Yates” on the top of a pink form.

“And is this your first visit to the Ministry?”

“No,” he snorts. “I’ll say it’s not.”

He has a sharp face, brown hair greased tightly back from his forehead, and a neat mustache. It’s difficult to tell his age. He could be twenty-five, but he could be ten years older. There’s something restless, something bristling, about him. Evelyn is used, now, to assessing the potential danger that might come her way; a woman was attacked once, a year ago, by a man with a knife. Her last female colleague. The woman spent the night in hospital and never came back.

“I’m getting less,” he says, extracting a packet of shag from his pocket and rolling himself a quick, expert cigarette.

She slides the ashtray in front of him. “Less money, you mean?”

“Yes.” He lights up and blows smoke into the air between them.

“This happens I’m afraid, Mr.… Yates.”

His eyes find hers through the smoke.

“May I ask what your injury was?”

“No, you may not.”

At this, she sees that the sheen has come off his cockiness somewhat. “All right,” she says. “That’s up to you.”

Buttocks then, or groin; those are the ones that never want to say.

He leans forward, jabbing the air with his finger as he speaks. “The only thing you need to know is I was on seventeen bob a week, and now I’m getting less.” His accent, she notes, is slipping a little now.

“Well,” says Evelyn, “you should know, Mr.… Yates, that for what the department calls second-grade injuries—and these are any injuries that do not include the loss of a limb—the payment drops after three years. Can I ask when the injury was sustained?”

“Nineteen seventeen.”

She opens her hands. “There we are, then. I’m sorry, Mr. Yates. You’re welcome to file an appeal.”

The man spits a stray piece of tobacco out onto the floor. “Is that it?”

“That’s it, I’m afraid.”

“You’re not going to tell me if I’m going to get more?”

Evelyn sighs. It astonishes her still that she is here, the mouthpiece for a committee that regards every claim as suspect, every man a malingerer, guilty until proven innocent, forced to plead for scraps from a government that has long since ceased to care.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Yates, but we’re only a first port of call. If you wish to file an official complaint, then we are able to register that complaint and forward it on. You should have a date for reassessment, which will include a medical examination, within the month.”

“Within the maaanth?” He leans forward, mimicking her accent. At this he is, she notes, not bad at all. “What about the benefits, then? How come if I’d stayed a private I’d be drawing more? Land fit for heroes, is it?”

He’s right. In a way, the ex-privates are the lucky ones; they have been given a small unemployment benefit. No such benefit has been given to the commissioned classes; they are supposed to have friends, or means. Temporary gentlemen have come down to earth with a bump. He leans back in his chair, pointing his cigarette at her as though deciding whether to fire. “Fucking woman.”

“Yes, well,” she says. “I’m afraid unemployed women haven’t been given any benefit, either.”

He looks as though he could spit.

She shoots a quick look over to Robin, but he is deep in conversation with a redheaded man in front of him. Something the other man has said has made him laugh.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Yates,” she says, turning back. “Now, if you’ll—”

“How many kids you got at home, then?”

“That’s none of your—”

“Five,” he says. “I’ve got five.” He coughs, then leans forward, lowering his voice. “You haven’t got any, have you?”

She says nothing.

“Spinster, aren’t you? I’ll bet you’re dry as a bone down there.”

Whatever sympathy she may have had is long gone. She imagines hitting him, or stabbing him in his hand with her pen.

“I bet you love this, don’t you? Up there on your high horse.”

“Of course I do,” she says, leaning back in her chair. “Do you want to know why?”

“Why?”

She leans forward again. “Because I’m a sadist.”

He opens his mouth, then closes it again. “Bitch,” he swears, under his breath, standing up, his chair legs scraping against the floor.

“That’s right, Mr. Yates. I’m a sadistic bitch.”

Then she reaches out a hand and, without looking up, puts the pink slip on the pile to be filed.

“Next!”

Thick bars of morning light stripe Hettie’s bed, touching the faces on the pictures above her, tacked in a careful arrangement on the wall: Vernon and Irene Castle in the middle of a fox-trot, Theda Bara, and, in a still from Broken Blossoms, Lillian Gish. Beside them are the Dixies, in a photo cut from the paper just before they left London: Billy Jones, Larry Shields, Emile Christian, Tony Spargo, and Nick LaRocca, brandishing his trumpet like a lethal weapon.

They all look happy this morning, grinning in the unexpected sun.

In the room behind her she can hear Fred getting ready to go out. Her mother has already gone to work, long before the light. Once Fred has gone the house will be hers for a few blessed hours till she has to leave for the Palais at twelve. She’ll boil some water and have her bath. First, though, she wants to lie here, in this lovely bit of sun, and think about the man from Dalton’s: Ed.

She closes her eyes and tries to conjure him. The smell of him. The way he danced. The way he talked, as though everything were a game: Two minutes constitutes a lurk.

No one has ever talked to her like that.

Behind her head Fred’s wardrobe opens with a judder she can feel through the wall. Hettie snaps her eyes back open, defeated. She can’t concentrate on anything good with her brother rooting around in there.

Fred woke her up again last night. It was just a few short shouts this time, and then he must have woken himself, because everything went quiet after that.

Clothes hangers clatter as he takes his jacket out. He gets dressed every morning and goes out, even though he hasn’t anywhere to go. Hasn’t got a job. Not since coming home from France, two years ago in December, just after their father died. For weeks after his demob, he didn’t leave the house; he just sat there, in their father’s armchair in the parlor. She would come back from work at Woolworth’s and he would still be in the same position as when she had left. Often, the dim light and something about the way he sat made her think it was her dad, come back from the dead. It gave her the creeps. But Fred just stayed there, hour after hour, as if that old armchair might tell him where to get a job.

That was when she had to start handing over half her wages. And there was Fred, just sitting there, doing nothing about it at all.

He wasn’t like that before. You couldn’t shut him up. He was annoying. He took up room. He would spread his bicycle bits all over the kitchen table and tease her about her dance classes and her film cards. He worked at the lamp factory down at Brook Green with their dad. They both used to set off together in the morning on their bicycles. Peas in a pod. Sometimes after work he would go to the pub and come back singing, and their mum would pretend to be angry, but you could tell she wasn’t really, because Fred was always her favorite. He had a girlfriend called Katy—who had hair so fair it was almost white and who smelled of pencil shavings since she worked at the stationer’s down by the tube.

He could be kind, too. Once, when he came back on leave from France, it was over Hettie’s birthday, and he wrote and asked her what she wanted. She’d asked to go to the theater, and he bought tickets for Her Majesty’s to see Chu Chin Chow. It was the first time she’d been to the West End, and the show was full of musical numbers and dancing and real animals on the stage. In the middle there was a zepp raid, and instead of going into the cellar with everyone else, they both went out on the street and shared a cigarette and watched the airships as they floated past in the late evening light, their bellies swollen like giant whales.

“Don’t tell Mum.” Fred had winked, as though they were in on it together, and she’d felt excited, and grown-up, and grateful for it all.

But the next time he came back from France he had changed. It was as though all of the noise and mess and life had been blasted out of him and only the empty, silent shell remained.

Hettie hears his footsteps pass her doorway now, his soft tread on the stair.

“Fred?” she calls out. He doesn’t reply, and she slides out of bed, goes over to the door, and opens it.

He is standing halfway down the stairs.

She leans on the banister above him. “Going out, then?”

He nods, cringing, as if caught in the act of something shameful.

“Where you off?”

“I’m just—” He shrugs, clears his throat, turning his hat in his hands. “Going down to the labor exchange. To have a see what’s what.”

“Going to try to get a job?”

There’s a horrible, stretched silence in which Fred’s cheeks flare a painful-looking red. He seems about to say something—but busies himself instead with straightening the brim of his hat. “’Spect so,” he says eventually. “Yes.”

Then he puts his hat on and almost runs down the stairs.

Hettie goes back into her bedroom, closing the door behind her and leaning against it.

He doesn’t go down to the labor exchange.

She saw him once, when he was out for one of his walks. Just shambling along, like an old man. He has become like those men from the Palais, the quiet ones: the ones who hire you and then shuffle around the floor, their silences like the thin skin on blisters, covering the things they cannot say.

Her eyes light on her dance dress, discarded by her bed.

If Fred got a job, at least she’d have a bit of money for clothes.

Why can’t he just move on?

Not just him. All of them. All of the ex-soldiers, standing, begging in the street, boards tied around their necks. All of them reminding you of something that you want to forget. It went on long enough. She grew up under it, like a great squatting thing, leaching all the color and joy from life.

She kicks her dance dress into the corner of the room.

The war’s over. Why can’t all of them just bloody well move on?

“Morning, Mrs. H. What can I get for you today?”

The butcher boy’s apron is red with wiped fingerprints. The smell in here is strong today, hitting Ada like a wall as she steps inside.

“What have you got that’s good, then?”

“This liver’s grand.” The lad presses the purple meat with his finger, and a small puddle of blood oozes onto the silver tray beneath.

“I’ll have some, and about half a pound of that beef.”

“Right-o.” The boy, whistling, turns around for his knife.

Ada takes her purse from her bag. There’s a cage of ribs laid out on the counter in front of her, the whitened bone sticking out of one end of the marbled flesh. The heavy smell seems to increase. She looks away, out onto the street, to where the sun is striking the ground. Two women stand beneath the awning of the fishmonger’s and a young man is walking past them, his head turned away from her.

The boy is slim and brown-haired. He looks like Michael. He looks like her son.

“Mrs. Hart?”

The butcher’s boy is handing the parcels of wrapped meat over the counter. Ada doesn’t take them. Instead, she rushes out onto the street. At first she can’t see him but then catches sight of the back of his head, fifty yards in front of her on the other side of the road. He is walking briskly, his arms swinging at his sides. She shouts after him, but he is too far away and doesn’t hear. A van makes its way up the road between them, cutting off her view with an advertisement: SUNLIGHT SOAP FOR MOTHER; a shy-looking girl in a blue pinafore and hat holds out a box of flakes. Ada weaves behind it. Her son is still there, walking steadily up the street in the sun, heading toward the park.

“Michael!” she calls, quickening her pace, but he seems to be moving faster than before. She tries to close the gap between them, keeping him in her sights. He looks well. She can see this, even from behind. He has both of his arms and both of his legs. He walks strongly and easily and his head is not bowed, and his hair is clipped just as it was the last day she saw him; and the sun is touching the tips of his ears, and whatever has happened to him, wherever he has been, he has come through it and is alive and well. She shouts his name again.

A small queue is gathered outside the grocer’s, but she pushes her way through it, feeling heads whipping around to stare. Her heart is racing now, sweat breaking at her hairline, on her back, and it is difficult to catch her breath, but the gap between them stays the same. He must feel her behind him, because he seems to be varying his pace to hers, as though they are playing some kind of torturous game.

When he reaches the top of the street, she sees him hesitate, finally, standing beside the ironmonger’s, as if deciding where to go, as if he is unsure, suddenly, of the way.

Turn left.

Go home.

He turns left, and she shouts after him as he disappears from view.

She lets herself slow a little, now that she knows he is heading home, but when she reaches the ironmonger’s, she sees the road to her left is empty. Her son has disappeared. An old man comes down the street toward her, moving slowly, a boxer dog snuffling the pavement at his side.

“Excuse me?” She goes to him and grips his arm. “Did you see someone come up here?”

“What’s that?”

“Did you see someone come this way? A boy? A young man?”

The old man, looking frightened, shakes his head. “No one, love. No.”

She releases him and leans back against the wall, gathering her breath.

“You all right?”

“Yes.” She nods. “Fine. I’m fine.”

She pushes off, hurrying, heading up the street that skirts the park, her thoughts jagged. Then it comes to her, and she could almost cry with relief, because she realizes he must have been running, when he saw where he was, when he knew how close he was, he must have run the last distance home. And she wants to run, too, but makes herself walk; she doesn’t want to be a hospital case when she reaches him, out of breath, unable to speak. Still, when she reaches the kitchen door she is shaking so much she needs both hands to turn the key.

Inside the house, everything is as she left it. The mangle in the corner, the air still heavy with heat and soap, the washing draped on the fireguard and hung on the dryer above her head. “Michael,” she calls, her voice deadened by the damp air. Then louder, “Michael? Are you there?”

She lifts the damp sheets. Looks behind chairs in the parlor. Stands at the top of the cellar steps and calls down into the musty dark.

Upstairs, the bedroom she shares with Jack is empty. She steps onto the landing and waits, outside the door of Michael’s old room, her heart hammering. Nothing but silence. Heavy silence. Thick. She pushes open the door with her hip.

The room is empty. She hesitates on the threshold, and then steps inside.

Months have passed since she has been in here. It is hard to breathe. She lifts the blanket and sees only unused sheets. She gets down on her hands and knees and stares at the empty air beneath his bed. Now there is only the wardrobe in the corner left. When she opens it, it smells woody, unused. There is nothing inside. Nothing but two empty hangers and a small cardboard box, tied tightly with string: a box tied so that no one would open it in a hurry; a box that hasn’t been opened in years.

Evelyn pushes Reginald Yates to the back of her mind and works steadily: each man a new piece of paper, each complaint copied down and registered on the correctly colored form. At a quarter to eleven she rings a bell and locks the door for a break. There’s a groaning from the men outside. It’s not too bad today, though. After the chill start the weather is mild, unseasonably so; the sun has been pouring through the front window of the office all morning, making the room stuffy. She could do with some air. She snatches her cardigan and cigarettes and pushes her way out into the dirty little courtyard at the back, where she leans against the wall and tips her head to the sky. Her neck is still sore from sleeping upright on the train last night. She puts her hand on her head and cricks it from side to side.

“Mind if I join you?”

She turns to see Robin in the doorway.

“I didn’t know you smoked.”

“I don’t. I’m having a fresh-air break,” he says with a smile. “If I’m not disturbing your peace?”

She shrugs.

Fresh-air break. Trust him to say something like that.

He takes a place against the wall beside her. “How are the troops, then?”

She lights up, blows out smoke, shrugs. “Same as ever.”

There’s a slight pause before he speaks. “I had rather an interesting one.”

“Oh?”

“Someone I’d known a little, before the war.”

“Really?” She looks up at him. “How?”

“We used to climb together.”

“Climb? Climb what?”

“Mountains.” He gives a brief, rueful smile. “We met in Wales. The hostel at Pen-y-Pass.”

She takes a drag of her cigarette. “That must have been nice.”

He either misses or ignores the sarcasm in her voice. “It was,” he says. “We were there in 1912. Again in ’13. We’d climb in the day and drink and talk at night. It sort of felt as though anything was possible.” He is staring straight ahead, as if his past is somewhere there, hovering in front of him, instead of a scrappy courtyard and a soot-blackened wall. “He lost a leg,” he says, “same as me.”

She looks up at Robin, properly, for the first time. He isn’t unattractive. Lots of people might even think him handsome. He is well built, with a broad body, a pleasant face. The sort of man that’s made for mountain peaks. But there’s something about him: his health, his niceness. The very idea of him exhausts her. She looks at her watch.

“Time to go back already?” He sounds disappointed.

“Yes.” She rubs her cigarette out on the wall behind her and pushes past him, back to her desk.

The cardboard box is beside her on the blanket. Ada isn’t touching it, though. Her hands are in her lap. But they are itching and her head is buzzing as though a swarm of bees is trapped inside.

Why has she seen him again? Why now?

Is it her? Conjuring him? Making her mind play tricks?

No. It is that cold, stuttering boy.

Reaching out for her.

Scuttling like a crab across the floor.

She lifts her head. The room around her is empty; the only signs left of her son’s habitation are the slight differences in color, the faint shadow of the paste Michael used to stick his football pictures to the wall. She puts her fingertips to them now, tracing their pattern.

Test me on the players. Go on, Mum.

Her son’s twelve-year-old face, screwed tight with concentration, as he sits in the kitchen after school, uniform on, with the door open to the garden and the summer afternoon outside:

Parker,

Jonas,

McFadden,

Scott.

Clapton Orient. The O’s.

Jack started taking Michael along to home games when he was six—his small hand clasped tight in his dad’s—and neither of them ever missed one after that, not as far as she can remember, right until they stopped the football in 1915. By that time all of the first team had joined up. Their picture was on the front of the newspaper, smiling away in their uniforms. That was the year of Kitchener, his image plastered everywhere: omnibuses, tramcars, vans; his finger accusing you from every last patch of wall. YOUR COUNTRY NEEDS YOU! Wherever you moved, he held your gaze. Guilty. That’s what he made you feel. She used to wonder how on earth they made it work.

At the last football match of the season all the players processed around the stadium, then walked down the High Road to show themselves off. Ada stood and watched with the rest of them, Michael in front of her, all of them waving and shouting themselves hoarse, cheering with the crowd.

The next day Jack found Michael down at the recruiting station, standing in the queue trying to join up. He pulled him out of the line by his ear and marched him up the road to their house. Michael was spitting. He couldn’t understand why they were making him stay at home when he had the chance to fight alongside his heroes.

The rows they had, after that.

Once, when Michael had stormed out of the house, she went up to Jack, who was standing by the sink, staring out the window. She touched him on the arm and he jumped as though he’d been burned.

“What?”

“Perhaps we should let him go,” she said. “The war will be over soon enough.”

Her turned on her: “You believe what you’re told, do you? That the war will be over? With Kitchener’s brave men?”

His contempt shocked her. Because she did believe it. It was everywhere that summer—a growing feeling of optimism, of hope.

They were all training: Parker, Jonas, McFadden, Scott, and the rest of the Clapton O’s. Joe White, Sam Lacock, and Arthur Gillies from their street—boys Michael had grown up with, just a little older than him. They and a million other young men were training, turning into the soldiers who would win the war.

The whole country was waiting that early, lovely summer of 1916, waiting for them to be ready, as though everyone was holding their breath.

The guns started in the last week of June. Ada could feel them from her Hackney kitchen, a sort of low booming, just on the edge of hearing, day and night for a week. Then they stopped. Half past seven in the morning, the first of July. She walked out onto the street of brown-bricked terraces, in the sudden silence of a midsummer morning in which the sun was already high. Other women were out there, too. Ivy White was there. She crossed the street toward where Ada was standing. “That’s it, then,” she said. “Isn’t it?”

She gripped Ada’s hands in her own slick wet ones. They were covered in suds. “They’ll be going over now, won’t they? It’s the end of the war.”

But it wasn’t the end. Jack was right. It was the beginning of something terrible and new. The papers printed the casualty lists, longer and longer each day. Ivy’s son Joe was missing, presumed killed. Ada would see her sometimes, at the end of the day, standing at the front window, looking out onto the street, expectantly, as if Joe were going to appear there, whistling on his way home.

Even Kitchener was killed. Drowned on his way to Russia. Sunk by a German mine.

Sometime at the end of that July she came home to find Michael sitting at the kitchen table, a newspaper open in front of him, his head in his hands.

“What is it?” she said. “What’s wrong?”

He looked up at her, his face white, shoved the newspaper toward her, and went outside.

At first she couldn’t see what he had been looking at. Then she saw the photograph: PRIVATE WILLIAM JONAS, CLAPTON ORIENT. His black hair was plastered down into a smart parting, his young face serious above the deep V of his strip. The paper said he had died in a trench alongside Sergeant McFadden. Beside his picture was a list of his football record: CENTER FORWARD—73 APPEARANCES, 23 GOALS.

Outside, there was the sound of a ball being kicked angrily against the wall.

She went outside, the paper held in her fist. “Look,” she said. “Look at me.”

Michael carried on kicking.

“Aren’t you glad you’re here?” her voice was high, uncontrolled. She didn’t care. “Aren’t you glad your dad brought you home that day? That you’re safe? It could have been you.”

He stopped the ball beneath his foot, and turned on her.

“Safe?” her son spat. “There’s no such thing, is there? Not for anyone, not anymore.”

She went inside, sat down, and held her shaking hands in her lap.

He was right.

And she knew then it was coming. That it was coming for them all. It was like the Bible, the stories she remembered from childhood, as though an order had been issued for all the boys to be killed.

The autumn came, the days began to shorten, and conscription began to take hold. She began to pray then—something she hadn’t done in years. She prayed selfishly, frantically, for herself, for Michael, for the war to stop at her door. She didn’t know who she was praying to, didn’t know who was more powerful: a distant God, who may or may not be listening; the hungry war itself, growling, just beyond the gates; or Kitchener, his weather-faded face half-covered over by adverts for Ovaltine and cigarettes, but his finger still pointing, still accusing from beyond the grave.

Michael’s birthday was February 20, 1917. The recruiting letter came in the first week of March.

The afternoon before he left for France, when he had finished his training and was home at the end of a week’s leave, she knocked on the door of his room. He was packing the last of his things, his big bag and greatcoat already waiting in the hall. He had his haversack open in the middle of the floor, and laid out around him in a fan shape were bits of his kit. She walked around the neat half circle he had made. Toothbrush, soap and small towel, two spare bootlaces, mess tin, fork and spoon. The window was open, and pale sunshine was filling the room. He looked up at her, squinting in the light. “You inspecting me, Mum?”

“Might be.”

He sat back on his heels. “Proper sergeant major you are.”

She crouched down beside him and picked up a small sewing kit, turning it around in her hands. “They teach you to use this, then?”

“Just a bit.”

She put it back in its place on the floor and went over and sat on the bed, watching her son. He was stronger-looking than when he’d left for his training. The soft, changing shapes of his boyhood were settling, the lines emerging of the man he would become. She watched his head as it bent and dipped, his long narrow back, the sunburned skin moving across the bone at the top of his spine. There was something hanging from his neck. “What’s that?” she asked, pointing.

He looked up at her and then followed her gaze down. “It’s my tag.”

“Can I see?”

He brought it out of his shirtfront, stood up, and walked over to her. “That’s my name,” he said, pointing at the brown fiber disc. “My regiment there. And my number.”

She stared at the number. Six digits. His pulse in the vein beside it, keeping time. Her son.

“You all right, Mum?”

“Grand.” She nodded, tucking the tag back into his shirt, doing the button up.

He left in the morning, before the sun was fully up. They had offered to walk him to the station, but Michael hadn’t wanted them to. They didn’t argue. They just stood together at the door and watched as he shouldered his pack, then waved his funny, overladen silhouette off, his tin hat bumping against the back of his neck. He turned, once, at the bottom of the road, and lifted his arm in the brightening morning, before he disappeared from view.

A train passes on the tracks outside, making the windows rattle in their frames.

Ada reaches out and brings the box into her lap. She tries to pick at the knot, but it is stubborn, tied so tightly that she’ll need something to open it with. She hesitates, briefly—but it is only brief, the hesitation, before she goes downstairs to fetch a knife.

“Afternoon, lovely.” Graham the doorman salutes Hettie with his good arm. “How’s my favorite dancer, then? You on a double today?”

“’Fraid so.” She leans into the little hutch where he sits by the door, oil heater on. It smells cozy—of warm wool and pipe. Graham is a fixture of the Palais. A brawny Cockney with an accent to match, he used to work on the railways before the war, and his stories are legion. It is said you can lose hours in his cubbyhole, emerge blinking in the light, and be ten years older, your youth stripped away:

One of the last to be called up.

Didn’t want an old bugger like me.

Proud to lose it in the end.

Two days till the Armistice!

Saw it there, twitching on the ground. Hand still moving.

Knew it was mine from the tattoo on the wrist!

“Commiserations,” says Graham.

“Need the money.” Hettie shrugs.

“Don’t we all. Hang on a sec.” He reaches into his pocket and pulls out a tin, opens it and takes a tablet out. “Here you go.” He passes it over the hatch toward her, a Nelson’s meat lozenge, brown-red. “Keep your strength up.” He winks. “Kept us going for hours, they did. Route marches. All the way ’cross France.”

This is what he always says.

“Thanks,” says Hettie, tucking it into her cardigan pocket. “I’ll keep it for later.”

This is what she always does. This is their little routine.

Does he suspect that she keeps the stinky little tablets only long enough to put them in the dressing room bin?

But it is their ritual, and she supposes it makes both of them feel good.

“I don’t know how you girls do it,” he says, shaking his head. “Dancing for hours. I really don’t.”

Hettie shrugs, as if to say, What’s to do?, then pulls her cardy round her, heading down the long, unheated corridor to the strip-lit dressing room at the end. The scattered girls turn to greet her, and they exchange hellos as she hangs her corduroy bag on the rail. Those girls who are changed already are sitting, chattering, puffing on illicit cigarettes despite the NO SMOKING signs nailed to the walls.

The chilly Palais dressing room is one of the dubious perks of the job. It’s not what you’d expect, though, from the ones out front, which are all decked out with Chinese wallpaper covered in pagodas and birds. The walls back here are just covered in paint, and a dismal green color at that. Some of the girls have scratched their initials into the plasterwork, which is already starting to peel. Some wit has even written a poem at knee height:

Beware old Grayson

If he thinks that you’re late, son

He’ll take behind and

He’ll give you what for.

When Hettie first started, she had to have it explained it to her: Grayson, the thin-lipped floor manager whose hard line on tardiness is legendary, is rumored to live out with another man somewhere in Acton Town. The boys swear he’s forever giving them lingering looks.

She takes off her cardy, blouse, and skirt, hangs them on the rail, and pulls on her dance dress, shivering in anticipation of the cold to come. Without the press of bodies that fill the Palais later in the week, the vast dance floor will be freezing. The management doesn’t allow you to take your woollies inside, so the girls try all the tricks they can, sewing extra layers under their dresses, or wearing two pairs of stockings, but nothing much will work on a frigid Monday afternoon; your only hope is to be hired and keep moving so you don’t have to sit still for long.

“Hey, Hettie!”

“Did you get in, then? Did you see it? Dalton’s? Saturday night?”

She turns to see that a ring of girls has gathered behind her, their faces expectant; hungry animals, waiting for the scraps. “Yes, we did.”

“So it’s real, then?”

“It’s real, all right. It’s so hidden, though, you’d never know it was there.”

The girls seem to exhale as one, and she can almost feel their breath alight on her, gilding her with their envy. She thinks of telling them about the dancers, about the way those people moved, as though they didn’t care, but it’s just too tricky to explain.

“And what about the band? Were they as good as the Dixies?”

“The band was killing.”

“And Di’s man? What’s he like?”

“Smitten. And rich.”

The girls sigh and draw away, back to the mirrors, their powder and cigarettes, giving last-minute adjustments to their faces, their hair. Hettie pulls her dance shoes out of her bag and sits down to buckle them on, warmed by a rare glow of satisfaction. She is envied for once. It may not be nice but it still feels good.

Di rushes in, just in time, pulling a face, whips off her coat, and changes at lightning speed, as the door opens and Grayson’s head appears around it.

“Time, ladies.” He claps his hands. “Out onto that floor.” He puts his head into the room and sniffs theatrically. “And if I catch any of you smoking that’ll be pay docked for a week.”

The girls move out into the chilly corridor, Hettie and Di at the back, the boys coming out of the dressing room opposite. Twelve of them, all dressed in their suits, ready for the afternoon shift.

The usual mix of feelings compete in Hettie as the dancers pass through the big double doors onto the floor. There is no doubt that the Palais is spectacular. Everything out here is Chinese: the whole dance floor covered by a re-creation of a pagoda roof; painted glass and lacquer panels showing Chinese scenes are hung around; and the ceiling is supported by tall black columns, all of which are decorated in dazzling golden letters. In the middle of the floor is a miniature mountain, with a fountain running down its sides, and beneath one of the two smaller replica temples, the band is warming up.

The first time she saw the Palais was when she came down for her audition on a cold day in January. Parts of it were still roped off, then, and the sound of hammering and sawing formed a background to the thumping piano accompaniment as Grayson drilled the hopeful dancers in front of a severe-looking woman who barked out orders and culled the men and women from five hundred to eighty during the course of the day.

Even then, in the club’s unfinished state, smelling of shavings and planed wood, you could feel it was going to be something special.

There were the adverts placed in all the local newspapers:

Palais de Danse

THE TALK OF LONDON!

Largest and most luxurious dancing palace in Europe!

Two jazz bands.

Lady and Gentleman Instructors.

Evening Dress Optional

Hettie used to cut them out of the paper and leave them on the kitchen table for her mother to read.

Six thousand people turned up that first weekend, and when Hettie stepped out onto the dance floor that first time, seeing the Palais in all its glory, it truly did seem like a palace.

But what Hettie soon came to realize was that none of its splendor was meant for the staff. It was all for the punters, for the ones who had paid their two and six. For Hettie and Di and the other dancers, the Pen waited. As it still waits.

They file in now, boys on one side, girls on the other, heads bowed as Grayson inspects the line for any cardigans or visible hankies, anyone slouching, any contraband cigarettes or knitting needles that might while away the dances that you spend unpicked. His gaze rakes them. General Grayson: That’s what the boys call him, especially the ones who were out in France.

Twelve boys and twelve girls a shift.

Twenty dances in the afternoon (3–6) and twenty-five in the evening (8–12).

Sixpence a dance.

“Bloody freezing in here tonight,” hisses Di, as Grayson stalks past.

Grayson stops. He turns, slowly, and Di looks down at her hands. But there’s no time for reprimands since the heavy door is opening and the punters are streaming through; hundreds of them, even on a Monday night, heavy-footed on the sprung wooden floor.

The band makes a bit of a ragged start and the first few couples brave it out. It’s always a waltz first at the beginning of the shift. Hettie surveys the scrappy scene, hands in her armpits against the cold. If people ever bother to wear evening dress to the Palais they definitely don’t on a Monday, and the dance floor is a sludge of brown and black and gray, the men in lounge suits, the women mostly in blouses and skirts.

An upright matron trussed into a woolen two-piece is crossing the floor with a determined stride, heading toward the male Pen. Di nudges Hettie and giggles. “Here she is.” Across the aisle, Simon Randall sits up straighter, spits surreptitiously onto his hand, and smooths down his hair. The woman stops before him, holding a ticket coyly in her hand. Simon, smirking, takes it and lets himself out. Hired. Simon is one of the most popular men, rented out two afternoons a week by this same woman at eleven shillings a time. Not including tips.

The crowd is scattered now, some of them sitting at tables, a few buying drinks from the little cabins around the sides of the floor. The cavernous room is filling up, the dance floor thickening, the band sounding stronger, the afternoon starting to find its shape. Hettie’s eye catches a tall man, moving slowly among the crowd on the other side of the floor, and she sits up, heart hammering. It looks like him, the man from Dalton’s: Ed.

The Palais? I went there once.

She grips the rail. Would he come here looking for her?

The man steps out onto the dance floor, and she leans forward, the better to see. She’s almost standing in her seat, but as he comes closer she sees it isn’t him. This man, other than being tall, is nothing like him; this man has the hesitant, shuffling gait of the false-legged. You can tell them a mile off. You have to be careful with them; they can trample all over you and not even know.

“What was that about, then?” whispers Di.

“Nothing.” Hettie, feeling cross, shakes her head.

But the man has had his attention caught and is making his way across the floor. She knows the look: a little vague, half-whistling through his teeth, as though he is pretending not to know how this business works. “Afternoon,” he says, hands in his pockets.

“Good afternoon.”

“How much is all this malarkey, then?”

“Sixpence,” says Hettie.

“Sixpence?” The man looks aggrieved, his voice rising a notch. “But I’ve just paid two and six to get in.”

“Come with a partner,” Di chimes in, “if you don’t want to pay.”

The man flushes crimson.

Hettie feels immediately terrible. Her heart wilts, for him, for her, for the whole damn business. “You buy your ticket over there,” she says gently, indicating the cabin to her left. “It’s a fox-trot next.”

The man swallows. “I’ll come back,” he says, “shall I?” His Shall I? is aggressive, daring her to say no.

“Yes.” She smiles at him. “Please do.”

The man walks stiffly away, as though if he bumped into anything he might break and he and his dignity smash all over the floor.

Di snorts. “That’ll be fun.”

“It’s all right for you.” Hettie turns on her. “I need the money. I haven’t got a man who’ll buy me things, have I?”

Di’s mouth rounds into a surprised little o. “What’s got into you, then? Get out on the wrong side of bed, did you?”

Hettie shrugs. She doesn’t know why, but she’s irritated with Di today. With the Palais. With all of it. The man is back, ticket in hand. She takes it from him, puts it in her pouch, and lets herself out through the small metal gate. And when she smiles at him, it’s not just for show, because, really, heaven knows what it must take them, any of them, to come here alone.

She lifts her arms, opens her palms.

This is how it works: You are hired, and you dance. If you’re nice to them, and they like the way you move, then they ask you for another, which means another sixpence, and so it goes. The management takes half your pay, so it pays to be nice.

The man’s hands are clammy as he pulls her close. He smells of sweat and basements and clothes that need a wash. He’s about as far from the man in Dalton’s as it’s possible to be.

That makes two of them, then.

The band strikes up, and they move out across the floor.

By three the queue in front of the office is almost finished, and only five or six men are left. Evelyn sits back in her chair, stifling a yawn. The man at the front of the line is eyeing her, hesitant, moving very slightly from side to side, as though the ground is shifting beneath his feet.

Shell shock.

Private.

“Come in,” she says. “Take a seat.”

He perches on the chair in front of her.

“Name?”

“Rowan.”

She unscrews her pen.

“Surname?”

“Hind.”

It’s such a lovely name that it stops her in her tracks. Hind: gilded and natural all at once. She glances up, finding herself looking more closely than she ordinarily would, searching for a corresponding beauty in his face. He is no beauty, though; too small for his demob suit, left arm in a filthy sling, he has the wizened, old-man look of those who have lived their lives skirting close to the edge. One of the ones who signed up for the grub.

“Rank?”

“Private, miss. As was.”

Her pen scratches over the paper. The afternoon sun warms her cheek. Hopefully, by the time she finishes, there will still be enough light to walk home through the park. “And what can I do for you, Mr.… Hind?”

“I was just passing,” he says. “And then I—I—”

She sits back. She is used to them: the stammerers, the stutterers. She can be patient when she wants to be; she can be kind. Rowan Hind’s gaze drops, and he is silent for a moment. Then, “Your finger,” he says, catching sight of it.

“Yes?”

“How did it go?” His pale eyes meet hers.

There is something strangely compelling about him, disarming; she decides to tell him the truth. “It was in a factory,” she says.

“The war?”

She nods.

“Munitions?” he asks.

“Yes.”

“Thought so.” He looks pleased. “Canary, weren’t you? You still got a bit of the yellow on your face.”

“Have I?”

“Did it hurt, then? Must’ve hurt.”

She looks down at the gap where the finger used to be, as the rest of her hand curls around it, a reflex, protective action. “It did,” she says. “Though not at first.”

At first she laughed. The astonishing sight of it: a finger. Her finger. Until a second before, attached to her hand. The strange, spacious moment before the blood burst out over her apron, her face. She remembers turning to the woman who was working on her left and seeing that her face, too, was spattered in blood. Then back to the machine, still stamping away, the finger inside it, the white tendon, stretched like glue. She remembers someone screaming. Then everything went black. By the time she came around she was bandaged and in an ambulance on the way to the hospital.

In front of her Mr. Hind is nodding away. “I saw that, too. Men lose their arm or leg, first few seconds they don’t know their arse from their elbow. If you were a soldier”—he leans forward, conspiratorially—“you’d get a pension for life.”

“Yes,” she smiles ruefully. “Well.”

She can see the man behind Rowan shuffling his feet.

“Was there a complaint?” she says. “Is that why you’re here?”

He seems to think about this, then, “No,” he says. “It’s not that.”

She waits for him to elaborate, but he simply sits there, staring at his hands.

“Are you working at the moment?”

“I’m working.” He lifts his eyes. “Salesman. Yes.”

“And how is that?”

He raises his thumb to his mouth, chewing a bit of skin at the side of his nail. “It’s terrible,” he says.

Of course it is. Do people like him, then, when he knocks at their doors? Traveling salesman? Little Mr. Hind?

“It’s not that, though,” he says. “It’s something else.”

“Yes?”

“I want to find my regiment. I want to find my captain. I didn’t know where to look.… And then I was passing, and I saw the sign. I was in the Seventeenth Middlesex, you see, fighting with Camden men, during the war.”

“I see.” She takes a scrap of paper from her desk and reaches for her pen. It’s not her job, but she can always go to the records office with her worker’s pass. Can always bend the rules from time to time. “It shouldn’t be too difficult. Providing, of course, that the man in question’s still alive. Shall I take your address first?” She unscrews the lid from her pen.

“It’s Eleven Grafton Street…Poplar.” He leans toward her, watching her write.

“And your regiment?”

“Seventeenth Middlesex.”

She writes this down. “And which years did you serve?”

“1916 until 1917.”

“And 1917 is when you were invalided out?”

“Yes.”

“And what was your injury?”

He hesitates. “My arm.”

“I can see that.” She waits for him to elaborate. “You can’t use it?”

“No.”

Again, he doesn’t say any more. She feels a small flicker of irritation. “And your captain?”

“Yes.”

“What was your captain’s name?”

His face twitches. “It was Montfort,” he says.

At first she thinks she has misheard.

“Captain Montfort.” He leans forward, waiting for her to write.

She looks down, to where her pen is held in her hand, pressing into the paper. The ink is running unevenly into the little gray marbled troughs and valleys. She lifts away the nib. “Captain Montfort?”

He nods.

“Well, I’m sorry.” She sits back. “I’m afraid I can’t help you with that.”

“What? Why?”

“We only deal with pensions here. Pensions and benefits. We are not a missing persons bureau.” She takes a slip from the pile beside her, turns it onto the blank side, takes out a small, leather-bound book, opens it, and copies out an address. She does everything slowly and carefully, keeping her pen as steady as she can. “I imagine the best thing to do would be to contact the army directly. All of the information is here.”

He looks at the piece of paper in her hand as if the letters are from a foreign alphabet. “But”—he looks up at her—“you said you could do it. You just said you could help.”

“I’m sorry. I was wrong.”

He is studying her fixedly. He knows she is lying, she thinks. She holds his gaze. His head starts to jerk.

“Mr. Hind?”

The jerks are rising in intensity, passing through his body, until he is moving like a jack-in-the-box and his face is contorted, horrible. But she has seen these fits before. However awful, you can do nothing but wait. She digs her nails into her palms and looks away at the stained brown-carpeted floor at her feet.

“All right, old thing?”

She looks up to see that Robin is standing directly in front of her, his hand on Rowan’s shoulder. For a second she thinks he is speaking to her. Then, “There, there.” He speaks quietly, as though calming an animal, his hand moving slowly up and down the smaller man’s back. “There.” He looks enormous beside Rowan, rooted as an oak. “There we are. That’s it. There.”

Slowly Rowan’s fitting stops, and he regains his self-control, breathing hard. Robin moves a little way away from him, allowing him space, creating a triangle between Rowan, Evelyn, and himself. He thrusts his hands into his pockets. “All right there, old chap?”

Rowan nods, his eyes on the ground. “Yes, sir. Sorry, sir.”

“There’s nothing to apologize for,” says Robin quietly. He looks at Evelyn. “Everything all right?”

“We’re fine,” she says, curtly. “Thank you.”

“That’s good, then.” He gives her a quick look, then walks back to his desk. She watches him go, blood raging; they all try it, at one time or another. Telling her what to do. She hates nothing more. She has been here for two years; she is the longest-serving member of the staff. She turns back to see that Rowan is staring right at her.

“You,” he says. He speaks slowly, as though pushing the words before him through something thicker than air. “You looked just like him, just then.”

“And who is that?”

“The man,” he says. “The man I want to see.”

“Well,” she says, passing the piece of paper over the desk toward him. “These are the people who will be able to tell you if—the man you’re looking for is still alive.”

The coffin is loaded into military ambulance number 63638. Alongside it are six barrels of earth, from six different battlefields, one hundred sacks in all. The ambulance sets off on the long straight road that leads north to the coast. A military escort accompanies it: two cars in front and one behind. Four soldiers sit silently in each car, their hats held on their laps.

The land here, though still ravaged, looks more like countryside than the Somme, farther south. Here signs of life are returning to the farms. Here, even after everything, fields still look like fields—like land where something still may grow.

The convoy passes a farmer on his plow. The farmer looks up at the escort and the scarred old ambulance as they pass by. He returned to this farm just last year. He was wounded at Verdun and lost an eye, and was released back home, secretly relieved. An eye seemed a small price to pay for his life. But he left the farm to stay with his father-in-law in Burgundy after the German advance in 1918, after the Germans raced forward in that spring offensive and requisitioned his farmhouse, his cellar, and his lands. After they drank him dry, killed and ate his chickens—stunned by abundance, boys who had been starving behind the lines. After they got so drunk that he and his wife and children were woken by them, shouting in the courtyard, naked, reeling, their helmets held on their crotches, empty bottles of wine rolling around them on the ground. He knew then that it was over. That the Germans were finished. That the advance had been stalled by these drunken, starving boys.

These are some of the pictures he carries of the war. Now he only wants to be left alone. He wants to get through his plowing without disturbing any ordnance that may have been left here. He knows of many farmers who have lost limbs, or worse, trying to make the most of their fields.

He wonders briefly who the approaching cars carry: a foreign dignitary, perhaps? But he doesn’t wonder long. He bends back to his work, hunched against the drizzle, against the gray skies, thinking of eating his dinner in front of the fire, sitting alongside his wife.

In one fierce, clean movement, Ada slices through the knots, and with a small puff that looks like smoke, the string falls away.

On the top are Michael’s letters to her and Jack, two thick piles of them, each held in place with another knotted piece of string. She lifts them out and puts them beside her on the bed. Not yet.

Lying beneath them is a smaller, loose collection of picture postcards. One is a picture of a church. Albert, it says, on the bottom right-hand corner. At the top of the bell tower is a statue of a woman with a baby, the woman holding the child in her outstretched arms, dangling it over the empty air. On the back, her son’s handwriting:

The woman is the Virgin Mary.

She’s been leaning like this for a couple of years.

They say if she falls then the war will be over.

Pray she falls when we’re winning Mum!

It was the first card he sent her, after he arrived in France in 1917, and the day she received it, she had tacked it up on the kitchen wall. It made her uneasy, though; there was something about that woman, dangling over the empty air, holding on so desperately to her child, that reminded her of herself.

She had the same chart on her wall as everyone else she knew; it had come free with the Daily Mail, and the town of Albert was right in the middle of the British Zone, marked red on the map. She drew a circle around it. Now she could picture him somewhere at least, could look at the church—see something that he had seen. It sounded like a good English name, too: Albert, easy in the mouth, not like some of the other names on the chart: Ypres, Thiepval, Poperinghe. She wouldn’t have had the first clue how to pronounce them.

She shuffles through the contents of the box. More postcards fall out from beneath that first: a picture of a river, and a riverbank, and picnicking people wearing summery clothes. THE SOMME, it says on the bottom. On the back of the postcard Michael had written, “It doesn’t look much like this anymore!” She remembers what she did when this postcard came to the door: searched the faces on the riverbank, relieved when the French didn’t look very different from the people at home.

The last picture is of the cobbled street of a town. Something is stuck faceup onto the back of it. She peels it carefully away; it is a photograph of Michael.

She remembers now: He sent it to her at the same time as the one that she has in the frame downstairs in the parlor, not long after he arrived. They must have been taken seconds from each other, and by the same photographer, because the same background—a painted wall—shows on each. He is not smiling here, though; his eyes are guarded and his edges are blurred, so that it is difficult to see where the wall ends and his uniform begins. She knows he must have moved as the shutter came down, and that this is the explanation for the way the photograph has turned out, but still, she doesn’t like it. It is as though he is already moving into a future in which he doesn’t exist.

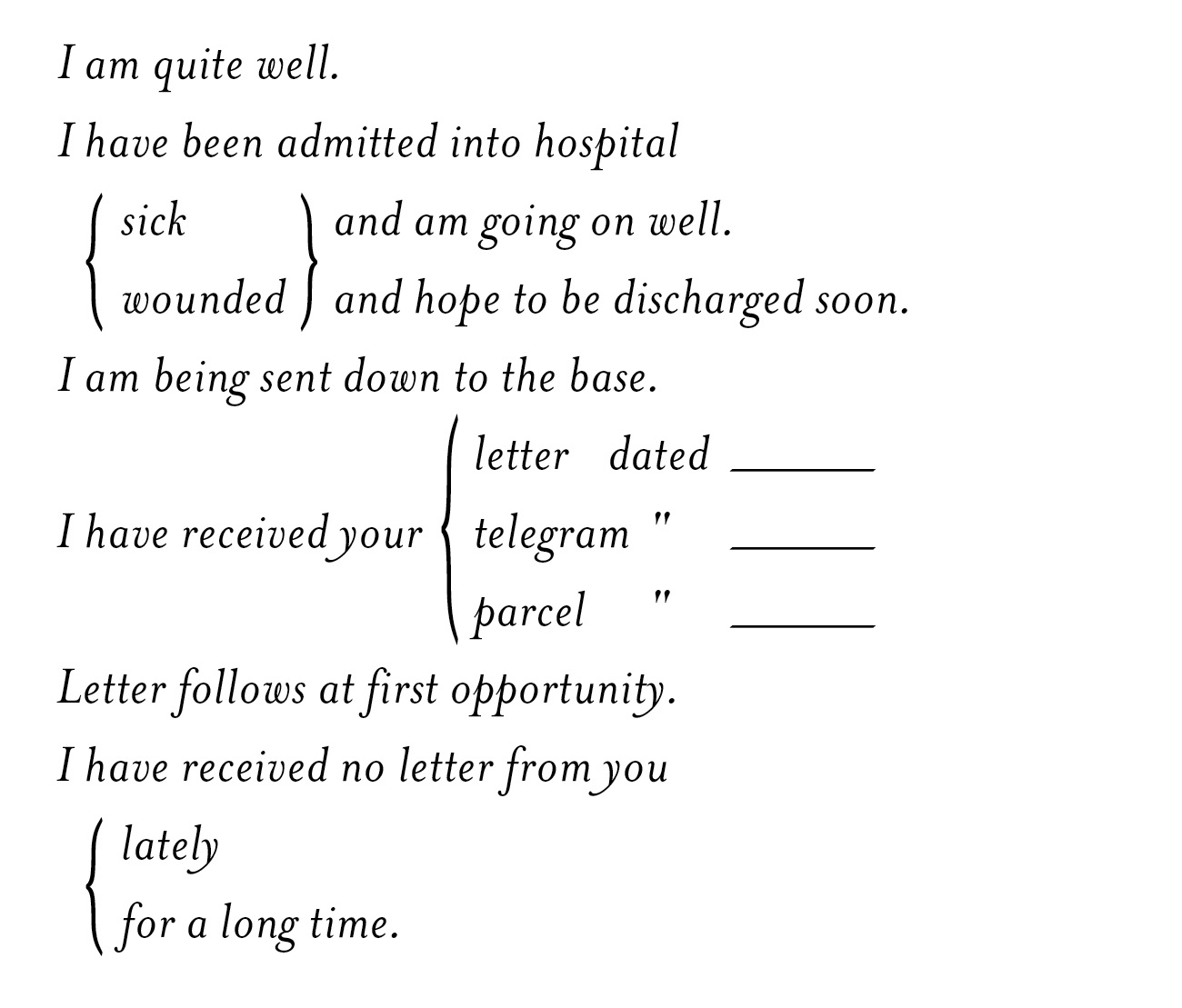

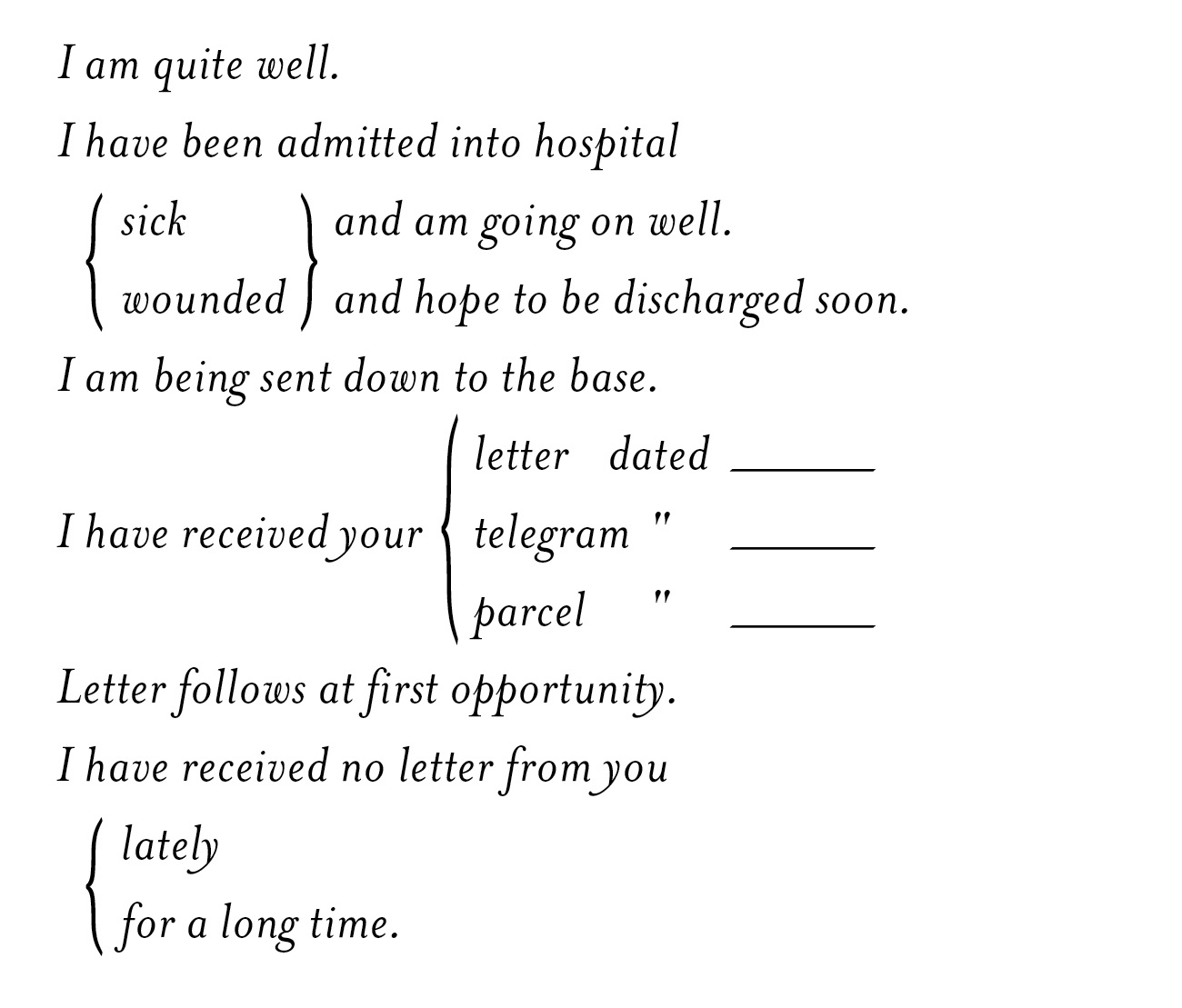

Underneath are three smaller pieces of light brown card. These postcards have no pictures on them, and each of them reads the same, with printed writing ranged all the way down the left-hand side:

The first two cards are from June 1917, from when he first went into battle. She remembers that they didn’t receive a letter for over a week, and then these postcards came, one day after the other, with all of the phrases crossed out except one: I am quite well.

How relieved she had been to get these, however little they said.

When they finally printed casualty lists for his company, she fell on the newspaper, running her finger down the list, frantically searching for his name among the injured and killed. It wasn’t there. Still, they had to wait a week for a proper letter from him. Meanwhile, she could read and try to understand what it meant: There had been fifty survivors from two hundred men.

And she knew then that, whatever her son had seen, it was something that took him somewhere far beyond her reach.

One more field service card remains in the box. This one is dated September 14, 1917. It came after two weeks of silence. Two weeks in which she had written to him four times. Two weeks in which every morning, when the mail came, she would run into the hall; in which every evening Jack would come into the kitchen, hat twisted in his fist, pretending that he wasn’t looking to see if there was a letter propped up against the teapot for him to read. This card, too, read the same:

I am quite well.

It was the last that they heard from him: September 14, 1917.

They scoured the papers, but this time there was nothing about his company. Nothing about any action they had been involved in, no clue.

At the bottom of the box is a letter in a small brown envelope. She takes it out and holds it in her hands. For something so heavy, it weighs nothing at all.

It arrived on a Monday in September, a day of late summer sun. She was hanging the sheets on the line. There were women out all the way along, doing the same, their gardens garlanded with flapping white. She hadn’t heard the tap of the letter box, and when she came back into the dim hall, she could just make out the shape of a letter lying on the mat. She bent to pick it up and saw a French postmark and Jack’s name in an official type. She dropped it on the floor and walked straight back outside.

There was the sun, hitting the whiteness of the sheets on her line, and all the way down the row of gardens, as though all the women of London were surrendering at once. Just in front of her was the rabbit hutch that Jack hadn’t got around to fixing yet. She stared at the place where the hexagonal wires were ripped away from the gray unvarnished wood. A fox had come and torn them years ago. Next door’s cat was sleeping beside it, lazy in a patch of warmth, its belly falling and rising in the sun.

The next thing she remembers is standing in the kitchen with the shadows lengthening around her, and Jack coming into the room. Holding the letter out toward her. Telling her to sit down.

“Don’t open it,” she said.

But he did. She watched his face as he read. His eyes as they moved along the page. Stop. Move back to the top. And in those tiny movements she felt her life, her future, contract and collapse.

“It’s not true.”

He put the letter on the table. Pushed it toward her.

She looked at her husband’s hands, at the spray of black hairs on the tops of his fingers.

“You have to read it, Ada.”

She took it from him.

Dear Mr. Hart,

I am very sorry to have to tell you that your son Michael died of his wounds on the 17th September.

Yours,

—

These were the only words, struck into the page. Not even a name, just a signature at the bottom, but blurred, as though it were written in haste, or in rain.

“It’s not true,” she said, looking up at him. “I’d have known if it was. It’s not true.”

No further letter came—nothing to say how their son had died. Jack wrote to Michael’s company, but they did not receive a reply. Everyone got two letters. Everyone Ada knew who had lost someone. Most got more than that: a letter from someone who had been there at the death, someone who had words of comfort, some small detail to impart.

She was sure there had been a mistake.

For a while afterward, people stopped her in the street to say how sorry they were. How he was a credit to her, as though in his dying he had somehow raised her stock. She just stood there while they talked, until they passed on again. She did not take out the mourning dress, packed in a chest at the end of her bed, folded with mothballs and tissue paper: the dress she wore last for her mother, twenty years ago.

Then, in the winter of 1918–19, when the war was over, the boys began to come home. They were everywhere suddenly, swarming the streets in their demob suits and fifteen-shilling coats. It was as though some contrary magic had occurred, over in France, as though, far from dying, they had flourished over there in the boggy fields, bred themselves again from the fertile soil. The papers were rife with stories, with miracles: boys who had been hiding behind enemy lines, had walked the whole way home, who hadn’t even known that the war had finished, but had turned up in the back garden ragged and filthy and in time for their tea.

That was when she saw him first: at the edge of a group of lads on a street corner, his back turned away from her. She went up to him; the boy turned, but it wasn’t him and she hurried away, sweaty, shaking. Then a few days later, there he was, arm in arm with a girl in the park. She started after him, calling his name. It wasn’t Michael. It kept happening. She would run after him, only stopping when she saw that it was someone else—someone the same height, with the same tilt of the head, or the same color hair. Or the boy she was following would simply disappear.

Often, restless in the night, she would leave Jack sleeping and climb into her son’s bed instead, lying on the narrow mattress in the narrow room, with the football pictures stuck to the wall. She began to see him there. She would wake to find that he was with her, sitting on the bed. She was never surprised. She reached for him, but he put his hand out, as though to stop her. There were shadows moving about nearby.

“Who are they?” she said to him.

“Shhh.” He put his finger to his lips and smiled. “Don’t worry, Mum, they’re all right. They’re only dead.”

One day, near the end of the long winter of 1918, a doctor came to the house. He gave her an injection, a quick scratch on her arm. When she came around she was back in the bedroom that she shared with Jack, and Jack was in the chair in the corner. The light was clear and cold. He came over and helped her to her feet.

“All right now,” he said. It wasn’t a question.

On their way downstairs they passed Michael’s bedroom. The door was open, the room stripped bare. Only the blank spaces and darker borders showed where his football pictures had been; only the tiny flecks of the flour and water that he had used as a paste. She looked into the room and back to her husband.

“Where are his things?” Her tongue felt too large in her mouth.

“I’ve put them away.” He looked guilty, but bullish, his jaw set tight.

She thought that she hated him then, but that even the hate seemed distant, as if it were happening to someone else—close, but hard to reach, as though trapped behind a pane of glass.

There’s a sound downstairs: The back door opening. Jack’s tread in the kitchen.

Ada scrabbles the postcards together. The sky outside the windows is dark.

“Ada?”

The meat, left at the butcher. The meal she was going to cook. The day, disappeared. Where has it gone? She pushes the letters down into the box, but the official letter she keeps out, slipping it into the pocket of her apron. She tries to tie the string, but her fingers are clumsy and it is useless and he is already on the stairs. She puts the box back in the wardrobe, closing it as quickly as she can. As Jack opens the door, she turns to him, smoothing down her hair.

“What are you doing?”

“Nothing—I—was…cleaning.”

“In here?” He looks at her empty hands, back up to her face.

“Yes—I—haven’t been in here for months, so…I thought I’d check, see if it needed anything.” Her heart is going like the clappers.

“Cleaning with what?”

“Nothing, yet. I was—just about to start.” She feels herself flush to the roots of her hair.

Jack looks around the room, takes in the bed, the scissors, still lying there. “Looks all right to me.”

“Yes,” she says. “It does.” She edges past him, picks up the scissors, and hurries downstairs, grateful for the cool, dim kitchen. She can hear his footsteps overhead. She listens as he walks across their son’s floor. It sounds like he is standing by the window, looking out. The footsteps turn, hesitate. Will he open the wardrobe? See that the box has been disturbed? She hardly dares breathe. But the footsteps cross the floor again, then leave the room and make their way downstairs. She reaches for the sink to hold herself up.

“Dark in here.” He comes into the room behind her.

“Yes.” She lights a match to the gas. Yellow light laps the walls.

“Is there nothing to eat?”

“I’m sorry. I—forgot.”

“You forgot?”

“Sorry,” she says, turning to him now. Twenty-five years. She waits for him to say something, to mention the date. But he doesn’t.

“I’m going to go and get a piece of fish,” he says eventually, steadily. “Would you like one, too?”

She nods, wretched.

He gets out his cap and puts it on. “I’ll see you later, then.”

She watches him go. Sinks to a chair. Thinks of the meat, left on the counter with the butcher’s boy. What must he have thought of her, that boy, running away like that? She puts her head in her hands.

Some silly woman, getting old.

Running after ghosts.

Shouting for her dead son in the street.

The field ambulance carrying the coffin passes the British and French troops who line the streets of Boulogne. It passes through the gates of the old town, then climbs the steep hill that overlooks the harbor, crossing the bridge that leads to the fortified entrance to the château and then under the great stone arch, drawing up in the courtyard, gravel crunching beneath its tires.

Eight soldiers carry the coffin along the twisting corridors of the old château, past waiting French troops, to the officers’ mess in the old library, where a temporary chapelle ardente, a burning chapel, has been ordained. The room has been decorated with flags and palms, its floor strewn with the yellow, orange, and red of autumn flowers and leaves.

A guard of French soldiers comes to watch over the body. All are from the Eighth Regiment and all have recently been awarded the Légion d’honneur for their conduct in the war. Candles are lit. The soldiers stand on either side of the coffin with their arms reversed, rifles held against their shoulders. One of them, a thirty-year-old veteran, looks briefly at the coffin before casting his eyes to the ground. The box is raw and rough—not the coffin of one who will be buried in state. He wonders if this understatement is a peculiarly British thing.

The British he knew in the war were crazy, funny men. One, in particular, he will never forget. He met him one night in an estaminet, just behind the lines. The English boy was eating egg and fried potatoes. That was what they all asked for, the Tommies, all the time, in their funny, blunt voices: all they wanted: Egg and chips! Egg and chips! This one was small and stocky. When the French soldier sat down in front of him with his beer and the Tommy looked up, the solider knew, without speaking, what they would do to each other before too long. And they did: at the back of a ruined church, by ancient gravestones, their bellies full of beer and fried food.

Afterward, he remembers, the boy broke down and cried. And he knew that it was not for what they had done, or not really, but for everything else. And they held each other, between the crumbled stones, until the birds started singing and a bleached sun rose over the remains of the church.

That was in June 1916, just before the Somme.

The French soldier stares at the ground, blazing with color in the candlelight. He looks at the leaves, at the flowers at his feet.