12

‘The Seizure of Power’

When Hitler was appointed Chancellor on 30 January 1933 the Weimar Republic had already ceased to function as an effective democracy. Under the authoritarian Presidential regime parliament and the political parties had been marginalized in the political process, the democratic ‘bulwark’ of Prussia had been destroyed by Papen, and, for some years, the state and the judiciary had been encouraging right-wing extremism. Nevertheless, at the turn of the year 1932/33, the NSDAP still had no more than one-third of the electorate behind it and it was by no means a matter of course that the whole of the state apparatus, as well as the wide range of very varied social organizations would simply yield to the Nazis’ drive for power. Significantly, the majority of political observers did not regard the new government as the start of a change of regime, but rather reckoned with another brief government that would soon be exhausted by the major problems confronting it.1 Thus the establishment of a dictatorship was not the inevitable result of Hitler’s becoming Chancellor. On the contrary, the transformation of the Presidential government of Hitler/Papen/Hugenberg into a Hitler dictatorship was a complicated process, lasting eighteen months and requiring a considerable amount of direction and great political skill.

Hitler was able to establish his dictatorship only because he had an army of millions of active supporters behind him bent on taking over power. However, this support was heterogeneous, with very diverse goals. The SA, nearly 500,000 strong, wanted first of all to take revenge on their political opponents; these so-called ‘brown shirts’, however, also assumed that under the new regime they would be rewarded for all their efforts and sacrifices during the ‘time of struggle’ and would be looked after in some way. The Party functionaries (the NSDAP had around 850,000 members at the beginning of 1933) were after jobs in the state apparatus; those small retailers organized in the Kampfbund für den gewerblichen Mittelstand [Combat League for Small Business] wanted to put an end to department stores; the members of the National Socialist Factory Cell Organization (NSBO) demanded workers’ participation in business; industrialists who supported the Nazis demanded an end to trade union representation on company boards; and journalists, doctors, teachers, and the like who were members of the Party’s professional associations wanted to dominate their various professional bodies. Thus, this very diverse movement wanted to bring every organization in the state and society under its control, and the Party membership’s ambition to take over power provided the real dynamic behind the measures adopted by Hitler and the Party leadership.

While Hitler and the Party leadership needed to keep these various, and to some extent contradictory, claims in view, to satisfy them, and in some cases to reconcile them, they had at the same time to make sure that these diverse ambitions did not undermine the alliance with the conservatives or damage the economy. Thus, it was vital to acquire power in stages, so as to allow the Nazis to concentrate on one goal, or a limited number of goals, at a time. Basically, this process took place in two stages. In the first, which lasted until the summer of 1933, political power was concentrated in the hands of the largely Nazi-controlled government. In the second, which came to an end in the late summer of 1934, the decisive moves were the action taken against the SA on 30 June 1934 and the take-over of the office of Reich President. These enabled Hitler permanently to exclude the conservatives from influence in the government, to eliminate opposition within the Party, and to establish a dictatorship without any constitutional limitations.

This chapter is concerned with the first phase, the period between January and the summer of 1933, in other words those months covering what is generally known as the ‘seizure of power’. In this analysis we are following the model of a ‘seizure of power’ in stages set out by Karl Dietrich Bracher over fifty years ago in his ground-breaking book, which is still essential reading.2 This model, however, shows clearly that the process was by no means automatic; Hitler intervened decisively at every stage and to a considerable extent controlled and steered the course of events.

Stage 1: Neutralizing the political Left

The first meeting of the new cabinet took place on the afternoon of 30 January. The following day, the Reichstag was supposed to be reconvening after a two-month break and Hitler pointed out that they would need the support of the Centre Party to secure a postponement, unless they were to ban the KPD and secure a majority that way. Unlike Hugenberg, Hitler did not want to go down that path as he feared serious domestic unrest and a possible general strike. So it would be best if parliament were dissolved, thereby providing the government with the opportunity to establish a majority through a new election.3 Thus, Hitler was demanding that his coalition partners immediately fulfil the important promise they had made to him just before his government took office.

On the evening of 30 January, the Nazis celebrated their triumph in Berlin with a torchlight procession lasting several hours through the government quarter. In Wilhelmstrasse Hindenburg received the ovations of the marching columns, which, in accordance with his wishes, included the Stahlhelm. However, the cheering was, above all, for Hitler, who appeared on a balcony in the Reich Chancellery. Goebbels immediately took advantage of his new powers by providing a running commentary on the radio.4

As Hitler had hoped, a meeting arranged for the next day with senior members of the Centre Party failed to reach agreement on the question of postponement. The Centre Party negotiators were understandably unwilling to agree to a suspension of parliament for a year without receiving guarantees of their influence on the government in the meantime. Hitler immediately used these reservations as an excuse to break off negotiations.5 At the next cabinet meeting, which took place on the same day, his conservative coalition partners were only too happy to agree with Hitler that future negotiations with the Centre were pointless and so they should call new elections.6 Hitler had initially kept the post of Minister of Justice vacant, leaving open the option of filling it with a member of the Centre Party. This reinforced the conservatives’ concern that he could after all arrange a coalition with the Centre Party behind their backs. For the time being, this option was now blocked and, on the following day, the conservative, Franz Gürtner, who had been Reich Minister of Justice under Schleicher, was appointed to the post. Finally, at the cabinet meeting of 31 January, Hitler noted that the cabinet were all agreed that these should be the last elections: a ‘return to the parliamentary system was to be avoided at all costs’.7 Hitler aimed to secure a majority for the Nazis mainly because he wanted to free himself from his reliance on the President’s authority to issue emergency decrees and so from his dependence on the right-wing conservatives.

On 1 February Hindenburg signed the decree to dissolve the Reichstag ‘after’, as Hitler made clear to him, ‘it has proved impossible to secure a working majority’, and he called new elections for 5 March.8 Up until then, the cabinet was able to govern by using the President’s right to issue decrees.

On the same day, Hitler put to the cabinet an ‘Appeal to the German People’, which he read out on the radio late that evening. He began with his usual narrative about the last – in the meantime – ‘14 years’ in which the country had presented ‘a picture of heartbreaking disunity’. Now, at the height of the crisis, ‘the Communist method of madness [is trying], as a last resort, to poison and subvert a damaged and shattered nation’. Everything was at stake: ‘Starting with the family, and including all notions of honour and loyalty, nation and fatherland, even the eternal foundations of our morals and our faith.’ Thus, Hitler continued with feeling, ‘our venerable World War leader’ had appealed ‘to us men, who are members of the nationalist parties and associations, to fight under him once again, as we did at the front, but now, united in loyalty, for the salvation of the Reich at home’. Employing a hollow and clichéd set of values, he referred to ‘Christianity as the basis of the whole of our morality’, the ‘family as the nucleus of our nation and our state’, the consciousness of ‘ethnic and political unity’, ‘respect for our great past’, ‘pride in our old traditions’ as the basis for the ‘education of German youth’. Hitler intended to improve the catastrophic economic situation by ‘reorganizing the national economy’ with the help of two great ‘four-year-plans’, which would secure the peasants’ livelihoods and start to get to grips with unemployment. ‘Compulsory labour service’ and ‘settlement policy’ were among the ‘main pillars’ of this programme. As far as foreign policy was concerned, the Chancellor contented himself with the comment that the government saw ‘its most important mission as the preservation of our nation’s right to live and, as a result, the regaining of its freedom’; he expressly committed himself to maintaining international limits on armaments. Hitler concluded by appealing to the Almighty to bless the work of the new government.9

On 2 February, the new Chancellor introduced himself to the Reichsrat [Reich Federal Council] and asked the state governments for support. The SPD and the Centre Party still had a majority in the Council, for Hamburg, Bavaria, Baden, and Württemberg were still not yet in Nazi hands, and in Prussia, thanks to a ruling by the Prussian Supreme Court of 25 October 1932, the constitutional and SPD-dominated Braun government was still able to perform certain functions, in spite of the appointment of the Reich Commissar the previous July.10 These included the representation of Prussia in the Reichsrat and Hitler inevitably regarded it as an affront that the Social Democrat civil servant, Arnold Brecht, in his reply to Hitler’s address warned him to obey the constitution and demanded the restoration of constitutional conditions in Prussia.11 Hitler was now more than ever determined to get rid of the opposition bloc in Germany’s biggest state, made up of the SPD and Centre Party. When the NSDAP parliamentary group’s motion to dissolve the Prussian parliament was defeated, he secured a Reich presidential decree ‘to restore orderly government in Prussia’,12 transferring all responsibilities from Prime Minister Braun to Reich Commissar Papen. Braun appealed against this breach of the Reich and Prussian constitutions and contravention of the Prussian supreme court’s judgment, but the issue was delayed until March and, finally, following Braun’s emigration, became redundant.13 Thanks to his new powers, Papen was able to dissolve the Prussian parliament on 6 February.14 Already on the previous day the acting government had dissolved all the Prussian provincial parliaments, district councils, city and town councils and called new elections for 12 March. This measure was aimed at getting control of the Prussian State Council, the Prussian second chamber.

On 3 February, the cabinet issued a decree ‘for the protection of the German people’, intended to facilitate the banning of meetings and newspapers during the coming general election. Hitler had rejected the original draft, which had gone even further, containing heavy penalties for strikes in ‘plants essential to life’, because it would have involved a public acknowledgement that the government feared a general strike. However, this fear was unfounded. Although, on 30 January, the KPD had called on the SPD and the trade unions for a joint general strike, the lack of preparations, the deep divisions within the labour movement, and the hopelessness of such a move – the regime controlled all the instruments of state power as well as the paramilitary SA and SS – prevented common action.15

On 3 February, the Defence Minister, General Werner von Blomberg, invited Hitler to meet the senior Reichswehr commanders for the first time. They met in the house of the Chief of the General Staff, General Kurt Freiherr von Hammerstein-Equord, where the new Chancellor expounded the basic ideas of his foreign and defence policy to the assembled company. After an introduction about the importance of ‘race’, Hitler quickly got to the main point: the current unemployment could be dealt with in only two ways: through an increase in exports or ‘a major settlement programme, for which the precondition is an expansion of the German people’s living space. . . . This would be my proposal’. In fifty to sixty years’ time they would then be dealing with a ‘completely new and healthy state’. ‘This is why it is our task to seize political power, ruthlessly suppress every subversive opinion, and improve the nation’s morale.’ Once ‘Marxism’ had been eliminated, the army would ‘have first-class recruits as a result of the educative work of my movement and it will be guaranteed that recruits will retain their high morale and nationalist spirit even after they have been discharged’. This is why he was aiming to acquire ‘total political power. I have set a deadline of 6–8 years to destroy Marxism completely.16 Then the army will be capable of pursuing an active foreign policy and the goal of extending the German people’s living space will be achieved with force of arms. The objective will probably be the East.’ Since it was ‘possible to Germanize only land’ and not people, in the course of the conquest they would have ‘ruthlessly to expel several million people’. However, they needed to act with ‘the greatest possible speed’ so that, in the meantime, France did not intervene and ally itself with the Soviet Union. Hitler concluded with an appeal to the generals ‘to fight along with me for the great goal, to understand me, and to support me, not with weapons, but morally. I have forged my own weapon for the internal struggle; the army is there only to deal with foreign conflicts. You will never find another man who is so committed to fighting with all his strength for his aim of saving Germany as I am. And if people say to me: “Achieving this aim depends on you!” Fine, then let us use my life.’17

In his speech Hitler had revealed not only his long-term plans for conquest and Germanization, but above all the basis for a close cooperation between the Reichswehr and his regime. In fact the aim of making the Reichswehr ready for war in six to eight years was entirely compatible with the military’s own rearmament plans.18

With his announcement that his movement would deliver the army first-class recruits and maintain the morale of the reservists even after their discharge, Hitler was recognizing the Reichswehr’s claim to dominance in the sphere of military policy, with the implication that in future the SA would be restricted to auxiliary functions. At the same time, it confirmed an agreement that he had made with Blomberg in the cabinet meeting on 30 January that, in contrast to its role under Papen and Schleicher, the army would, as a matter of principle, no longer be used to support the government in domestic politics and instead concentrate entirely on its role as a future instrument of war.19

A few days later, the close cooperation between Hitler and Blomberg was given practical expression. At the cabinet meeting on 8 February Hitler emphasized that ‘the next five years must be devoted to the remilitarization of the German people’; every publicly supported measure to create work should be judged on whether it was necessary for this purpose.20 However, at this point, as he openly admitted to his cabinet, Hitler was in any case not prepared to authorize a major programme of pump-priming the economy – for electoral reasons. Issuing more credit was liable to meet with opposition from his conservative coalition partners.21

Thus, contrary to Hitler’s bombastic announcement of 1 February, the new government confined itself to using the money provided by the Schleicher government for work creation, which had been financed with credit. This occurred the following day at a cabinet committee presided over by Hitler with 140 million RM to distribute. They decided to provide 50 million RM for the Reichswehr and 10 million RM for aviation. Defence Minister Blomberg explained that the Reichswehr had launched ‘a large rearmament programme spread over several years’; he was referring to the so-called Second Rearmament Programme, which had been agreed in 1932 in anticipation of the lifting of the Versailles Treaty’s restrictions on armaments, and was intended to start on 1 April 1933.22 Blomberg asked Hitler directly to approve the finance for the whole programme, which was costed at around 500 million RM. Hitler agreed that rearmament would require ‘millions of Reich Marks’ and was ‘absolutely’ decisive for the future of Germany. ‘All other tasks must be subordinate to the task of rearmament.’ The cabinet also approved the statement by the Reich Commissioner for Aviation that he had agreed a three-year ‘minimum programme’ with the Defence Ministry costing 127 million RM.23

After only a few days, therefore, it was apparent that Hitler’s determination to rearm Germany, was matched by a military leadership that was about to ignore the military restrictions of the Versailles Treaty. It was true that the Second Rearmament Programme, with its planned expansion of the 100,000-strong professional army by 43,000 professional soldiers over five years and the training of 85,000 short service volunteers per year, was relatively modest. However, already on 1 April 1933, as the first stage, 14,000 professional soldiers were to be recruited in contravention of the provisions of Versailles. It was impossible to keep this secret over the long term. In other words, the military were determined to overcome the Versailles armament restrictions – either within the context of an international disarmament agreement or through independent action by Germany – and Hitler was only too ready to adopt these concrete rearmament measures himself.24 From the point of view of the generals his ‘take-over of power’ could not have come at a better time.

Now it was a matter of making sure these plans could be realized. The NSDAP totally dominated the campaign for the Reichstag election of 5 March.25 The Party concentrated its campaign entirely on Hitler; ‘Hitler is going to rebuild’ was the slogan, which once again aimed at arousing vague emotions – trust and hope – while dispensing with concrete political aims. At the cabinet meeting on 8 February Hitler had recommended that ‘election propaganda should, if possible, avoid all detailed statements about a Reich economic programme. The Reich government must win 18–19 million votes. An economic programme that could win the approval of such a huge electorate simply does not exist’.26 The second theme of the NSDAP campaign was the struggle with the left-wing parties. On 8 February, Hitler bluntly told a group of leading journalists: ‘In ten years’ time Marxism will not exist in Germany’.27

On 10 February, for the first time since his appointment as Chancellor, Hitler spoke at a mass meeting in the Berlin Sportpalast. The speech, introduced by the head of the Party’s propaganda Joseph Goebbels, to create the appropriate ‘mood’, was broadcast by all radio stations and designed to project the energy with which the new government intended to solve the crisis and unite the nation. After ‘14 years’ of decline they must ‘completely rebuild the German nation’. ‘That’, as Hitler taunted his political opponents, ‘is our programme!’ He was not, however, going to provide any further details. Instead, he reached the high point of his rhetoric, an ‘appeal’ to his audience: ‘. . . Germans, give us four years and then assess us and judge us. Germans, give us four years and I swear that, just as we, and just as I, have taken on this office, I shall then leave it.’ Hitler finished with a kind of confession of faith in the German people, which in its cadences and formulation was intended to be reminiscent of the Lord’s Prayer:For I must believe in my nation. I must hold on to my conviction that this nation will rise again. I must keep loving this nation and am utterly convinced that the hour will come when those who hate us today will be standing behind us and will join us in welcoming the new German Reich we have created together with effort, struggle, and hardship, a Reich that is great, honourable, powerful, glorious, and just. Amen.28

During the following days and weeks there were more mass meetings, modelled on the Sportpalast one, in Stuttgart, Dortmund, and Cologne, introduced by Goebbels in the guise of a ‘reporter’. Radio had already been used for government propaganda under Papen, but the broadcasting of election meetings was new. Some states that were not yet in Nazi hands raised objections to this breach of radio’s party political neutrality. On 8 February the cabinet had agreed the following arrangement: Hitler would be given privileged access to radio only in his capacity as head of the government, not as a party leader; Goebbels’s introductions should not exceed ten minutes, a limit which Goebbels did not, of course, abide by.29

At this point, the regime took tough action against the Left. On 1 February, Göring had already issued a general ban on KPD meetings in Prussia, which the other Nazi-controlled states (Brunswick, Thuringia, Mecklenburg, Oldenburg, and Anhalt) then also introduced; the communist press could not appear regularly as a result of numerous bans, so that the party’s election campaign soon came to a halt. Karl Liebknecht House, the KPD’s Berlin headquarters, was repeatedly searched and, on 23 February, shut down altogether. In response, after 7 February, the party began adopting illegal methods of operating, but worked on the assumption that there would not be a ban before the election. In the second half of February, the SPD’s campaign was also significantly restricted by bans on meetings and newspapers and the large-scale disturbance of its meetings by Nazi mobs.30 The two workers’ parties, which had been engaged in a bitter struggle since 1918/19, had no means of countering these attacks: they did not have the resources for an armed uprising and they were not geared for a general strike or even for continuing political work underground. On the contrary, the SPD tried to keep its struggle against the government within legal bounds for as long as possible.

However, the repression did not affect the Left only. On 15 February, Hitler used a big meeting in Stuttgart to mount strong attacks on the Centre Party, which in Württemberg formed the majority of the government. However, political opponents interrupted the broadcast of the meeting by cutting the main cable. The cabinet regarded this action as ‘sabotage’ and a ‘major blow against the authority of the Reich government’.31 Hitler’s Stuttgart attacks on the Centre marked the start of a Reich-wide campaign against the Catholic party, which in the light of the ‘Stuttgart act of sabotage’ increased in intensity and in some cases became violent. Centre Party meetings and newspapers were banned; civil servants who were party members were, like Social Democrats, suspended or dismissed;32 a torchlight procession of Centre Party supporters, following a meeting with Brüning in Kaiserslautern, suffered an armed attack. Following a subsequent complaint by the chairman of the Centre Party in the Rhineland to the Reich President and the Vice-Chancellor about the continuing ‘terror’, Hitler felt compelled to intervene.33 A major offensive against the Centre Party at this point did not suit his intentions. Thus, acting on his authority as Party leader, he ordered a stop to the attacks by Nazi activists with the statement: ‘The enemy that must be crushed on 5 March is Marxism! All our propaganda and thus the whole of the campaign must concentrate on that!’34

And that is exactly what happened during the remaining two weeks before the election. It now became apparent how Papen’s 1932 Prussian coup played into the hands of the NSDAP. Göring, who had taken over the Prussian Ministry of the Interior in an acting capacity, systematically purged the top ranks of the Prussian administration and police of democratic officials.35 On 17 February, he instructed the police to provide the ‘nationalist leagues’, the SA, SS, and Stahlhelm, and the propaganda of the government parties with wholehearted support. By contrast, they should proceed against the agitation of ‘organizations hostile to the state’ with all means at their disposal and, if necessary, ‘make ruthless use of their weapons’.36 On 22 February, he ordered the creation of (armed) auxiliary police units from members of the SA, SS, and Stahlhelm. Simply by putting on an arm band, members of paramilitary leagues became enforcers of state policy.37

On 27 February, the cabinet agreed a decree that not only increased the penalties for espionage, but was above all directed against ‘activities amounting to high treason’, including resistance to the police and military, as well as calls for general and mass strikes. The Justice Minister Gürtner’s desire to publish the decree before election day shows that the new government was hurriedly creating a new weapon that would enable it to crush any opposition effectively and conclusively.38

Meanwhile, Hitler had been continuing his election campaign with mass meetings that were broadcast on the radio.39 On 20 February, he was able to fill the NSDAP’s election campaign coffers; at Göring’s official residence in Berlin he addressed two dozen leading industrialists whom he promised that ‘Marxism’ would be ‘finished’ either in the coming elections, ‘or there will be a fight fought with other weapons’. In the end, he ensured that the guests agreed to put up a total of three million RM, which the NSDAP urgently needed to finance its election campaign.40

Stage 2: The removal of basic rights

During the night of 27/28 February, the Reichstag was set on fire. To this day the background to this event has remained obscure and may well remain so. The Nazis’ claim that the fire was started by the KPD as a signal for an uprising can be dismissed; it proved impossible to provide any decisive proof. On the contrary, the Reich Supreme Court was obliged to acquit the accused communist functionaries and it was to become clear that the communists were totally unprepared for an uprising.41 The second explanation, according to which the 24-year-old Dutch worker, Marinus van der Lubbe was solely responsible for the fire, has dominated research for a long time. Its main flaw is that it is difficult to see how a single individual could set fire to and destroy such a large building. The third explanation, which blames the fire on a Nazi plot, possibly organized by the President of the Reichstag, Hermann Göring, is plausible given the systematic persecution that followed, but cannot be adequately proved.

The debate between the supporters of the Nazi plot idea and those claiming a single individual was responsible has been shaped by two important alternative theories about the functioning of the Nazi state: on the one hand, the assumption that the seizure of power was carefully planned, and on the other that the Party leadership had largely improvised its take-over.42 However, these alternative explanatory models do not necessarily contribute much to answering the question: who started the fire? In fact, this question is basically of secondary importance for the history of the seizure of power and Hitler’s role in the process. What is decisive is the fact that, as early as that night, he used the situation to introduce extensive emergency powers, thereby removing legal restrictions on the persecution of his political opponents and establishing arbitrary rule.

Hitler was spending the evening of 27 February with Goebbels when he received the telephone call informing him of the Reichstag fire. They both quickly set off for the parliament, where Göring and Papen were already waiting for them. They soon agreed that the communists must have been responsible. After an initial consultation with Papen, Hitler met Goebbels, who, in the meantime, had mobilized the Gau headquarters, in the Kaiserhof. It is clear from Goebbels’s diary that they were not exactly concerned about a communist uprising: ‘Everyone’s delighted. That’s all we needed. Now we’re really in the clear.’43 Hitler and Goebbels drove from the Kaiserhof to the editorial offices of the Völkischer Beobachter, where Hitler personally took over redesigning the next issue.44

The impression given by Goebbels of a very calculating and determined Hitler, coolly using the situation for his own ends, is reinforced by the measures he took the following day. At the cabinet meeting on the morning of 28 February 1933 Hitler announced that ‘a ruthless confrontation with the KPD was now urgently necessary’, the ‘right psychological moment’ had arrived, and the fight against the communists must ‘not be made dependent on legal considerations’. Göring stated that ‘a single individual could not possibly have carried out the arson attack’.45 A second cabinet meeting, which took place in the afternoon, agreed the Decree for the Protection of People and State, thereafter often termed the Reichstag Fire Decree.46 Suspending ‘until further notice’ the basic rights of the Weimar constitution, it imposed restrictions on personal freedom, free speech, and freedom of association, and authorized interference with postal communications, house searches, confiscations, and limitations on property rights. In addition, the decree authorized the Reich government to take over power in the individual states, on a temporary basis, in the event that the measures taken by the states proved inadequate ‘to restore law and order’. In effect, the government was usurping the Reich President’s constitutional right of intervention; the federal structure of the Weimar Republic, the careful balance between the Reich and the federal states, was history. Moreover, the death penalty was introduced for a whole series of offences, to enable the regime ruthlessly to crush resistance.47 The state of emergency created by the decree was to remain in force throughout the Third Reich. Hitler’s regime was based from start to finish on depriving the nation of its basic rights.

That very night thousands of KPD functionaries were arrested in Prussia, using comprehensive lists prepared under the Papen and Schleicher governments in case of a communist uprising; the other states soon followed suit. On 3 March, the police achieved an important coup by arresting the party’s chairman, Ernst Thälmann. The party machine was systematically destroyed just at the point when it was preparing to go underground.48 Göring also had the whole of the SPD press in Prussia banned for a period of fourteen days and renewed the ban several times until 10 May, when the party’s newspapers were confiscated. It was only outside Prussia that a few papers could continue to be published until the beginning of March.49 Philipp Scheidemann, Wilhelm Dittmann, and Arthur Crispien, all members of the SPD central committee, had fled to Austria before the Reichstag fire; at the beginning of March, the former Prussian prime minister Otto Braun and the former Berlin police president, Albert Grzesinski, went abroad too.50 The Reichstag Fire Decree also gave the government the pretext for arresting unpopular intellectuals, for example, Carl von Ossietsky, Erich Mühsam, Ludwig Renn, Egon Kisch, and the lawyer Hans Litten, who had caused Hitler so much embarrassment in a Berlin courtroom in 1931.51

After issuing the emergency decree, Hitler returned to the election campaign, speaking on 1 March in Breslau, the following day in the Berlin Sportpalast, and on 3 March in Hamburg.52 Finally, on 4 March – government propaganda declared the Saturday before the election to be the ‘Day of National Awakening’ – Hitler made an appeal to the electors from Königsberg, the capital of East Prussia. His speech was not only broadcast on the radio but was also carried over loud speakers, installed in public squares throughout the Reich. In Berlin alone Party formations were involved in twenty-four public demonstrations in various parts of the city. Hitler used his appearance above all as a massive denunciation of the ‘November criminals’ and, as usual, refrained from making any concrete statements about his government’s future policies. According to Hitler, when asked by his opponents about his ‘programme’, there could be ‘only one reply: “the opposite of yours”’.53 At the end, in a solemn conclusion, his audience in Königsberg, but also the masses all over the Reich listening to the loudspeakers, began singing the ‘Netherlands Prayer of Thanksgiving’, consciously taking up a tradition from pre-war Germany, when it was played on important occasions.54 The transmission ended with the pealing of the Königsberg church bells.

On election day, the new government was already in a position to dominate the streets throughout the Reich. Swastikas and black-white-and-red flags were ubiquitous; the coalition parties’ posters were prominent everywhere, while those of the opposition parties were banned. The streets were patrolled by the SA and the police, armed with rifles.55 In the end, the NSDAP managed to win 43.9 per cent of the vote. Together with their coalition partners, the DNVP, who had adapted themselves to the new era by fighting the election under the name Kampffront Schwarz-Weiss-Rot [Combat Front Black-White-Red (the colours of the pre-1919 Reich)], they had an overall majority of 51.9 per cent. This meant that the NSDAP had managed to increase its hitherto highest vote of July 1932 by 6.5 per cent (compared with its vote in November 1932, by 10.8 per cent). The biggest losses were suffered by the KPD (4.6 per cent) and SPD (2.1 per cent). In view of the massive obstacles placed in the way of the left-wing parties and the numerous advantages gained by the NSDAP since 30 January, the result was worse than expected by Hitler and the Party leadership. The NSDAP was still dependent on its coalition partner.

Stage 3: ‘Cold revolution’

Hitler was certainly exaggerating when he claimed in the cabinet meeting of 7 March that the election result was a ‘revolution’.56 But what followed – a mixture of illegal actions by the Party rank and file and quasi-legal measures by the government – did indeed, within a few weeks, revolutionize Germany’s political system.57 Goebbels described this process accurately as a ‘cold revolution’:58 through a series of actions resembling a coup d’état the government destroyed the constitutional order, concentrating power in its own hands.

To begin with, it set about ‘coordinating’* the states not yet controlled by the National Socialists. With the Reichstag Fire Decree the Reich government had expressly given itself the authority ‘temporarily’ to take over ‘the powers of the highest authorities in a state’ in order to ‘restore law and order’. Hamburg, which was ruled by a coalition of DVP, DSt.P, and SPD, was the first casualty of this clause.59 The Social Democrat members of the senate had already resigned on 3 March, in order to avoid giving the Reich a pretext to intervene in Hamburg’s affairs. The following day, the first or senior mayor, who was a member of the Deutsche Staatspartei, also resigned. This prompted the local National Socialists to demand the post of police chief and, when the senate refused, on 5 March – election day – the Reich Interior Minister, Frick, simply stepped in and appointed an SA leader as acting police chief. In February, with the aim of conciliating the bourgeois parties, the Hamburg Nazis had already proposed – naturally with Hitler’s approval60 – a non-Party figure and leading business man, Carl Vincent Krogmann, as first mayor. This proved successful: on 8 March, a new senate was formed under Krogmann’s leadership, including the bourgeois parties. During the following days, similar developments occurred in the other states: on 6 March in Bremen and Lübeck, on 7 March in Hesse, on 8 March in Schaumburg-Lippe, Baden, Württemberg, and Saxony. Only Bavaria was not yet subject to Nazi rule; but, on the evening of 8 March, Hitler and his closest advisors decided to put an end to this state of affairs.61

In Munich ‘coordination’ ran as smoothly as in the other states. The reassurances that the leader of the Bavarian People’s Party, Fritz Schäffer, had received from Hindenburg on 17 February, and prime minister Heinrich Held had received from Hitler on 1 March,62 that the Reich would not intervene in Bavaria proved completely worthless. As had been agreed in Berlin the previous evening, on 9 March an NSDAP delegation, led by SA chief Röhm and Gauleiter Adolf Wagner, demanded from prime minister Held that a member of the delegation, Ritter von Epp, be immediately appointed general state commissar. The large numbers of SA marching around the city provided a suitably threatening backdrop to their demand. The Bavarian government refused to agree; but that evening Frick transferred the powers of the state government to Epp on the grounds that ‘the maintenance of law and order in Bavaria is currently no longer being guaranteed’.63 That same evening Held complained both to Hitler and to Hindenburg. The Reich President instructed his state secretary to find out from Hitler what was going on, and then accepted his explanation that the situation could not be dealt with in any other way.64 Epp now took over power without more ado and, after a few days, Held was forced to go. This was the same Held who, eight years before, had made Hitler promise that his party would abide strictly by the law.65

At the beginning of March, in moves often directly linked to the ‘seizure of power’ in the states, the Nazis also took over the administration in numerous towns and cities. Typically, the SA occupied the town hall, drove out, and in some cases mistreated, the councillors, and hoisted a swastika on the roof. The local government elections, called by the new government for 12 March, were immediately followed by another wave of take-overs in numerous towns and villages in which the Nazis had hitherto been unable to make an impact.66

Immediately after their election victory of 5 March, the Nazis also increased their anti-Jewish attacks, directed above all against lawyers and businesses, throughout the Reich.67 But, department stores, one-price shops, co-op stores, in other words businesses (whether they were Jewish or not) which the Party had attacked for years as unfair competition for ‘German’ retailers, were also targeted by activists. Party supporters, above all Storm Troopers and members of the National Socialist small business association, demonstrated in front of the shops, prevented customers from entering, and stuck notices or scrawled slogans on the shop windows. This often led to disturbances. On 9 March, SA formations marched to the Berlin stock exchange to try – unsuccessfully – to force the resignation of the ‘Jewish’ board.68 While some leading National Socialists (for example Göring, with his announcement of 10 March that he refused to accept that ‘the police should be a protection force for Jewish department stores’69) encouraged such attacks, Hitler, conscious of the need to consider his conservative coalition partners and the economic situation, was obliged to calm things down. On 10 March, he issued a statement forbidding ‘individual actions’ and he used a radio broadcast on the ‘National Day of Mourning’ to underline this ban and to demand ‘the strictest and blindest [sic!] discipline’.70 As a result, with a few exceptions, the attacks decreased.

The government responded differently to the attacks on Jewish lawyers. In this case, official statements actually encouraged the occupation of court buildings and the expulsion of Jewish judges, prosecutors, and attorneys. These attacks were not simply an expression of radical anti-Semitism; rather, they represented an early trial of strength with the state apparatus, for they challenged the rule of law, preparing the way for legal interventions in the judiciary and civil service.71

During this period, Hitler sought to demonstrate his solidarity with conservative Germany. On 10 March he ordered that all public buildings should fly the black-white-red flag to mark the National Day of Mourning.72 This was very much in accordance with the views of Hindenburg, who on the following, day sent a flag decree to the Reich Chancellery,73 which Hitler then announced in his radio broadcast of 12 March: ‘until the final decision concerning the Reich colours has been taken, the black-white-red flag and the swastika are to hang side by side’, as this would link ‘the proud history of the German Reich with the powerful rebirth of the German nation’. However, Hindenburg had also instructed that the Reichswehr was to use only the black-white-red flag, thereby demonstrating that he continued to regard the army as being above party. Hitler also announced a decree from Reich Interior Minister Frick that to ‘celebrate the victory of the nationalist revolution’ all public buildings should be decorated with flags in the new form for three days.74 This gesture was a foretaste of the ceremonies envisaged for the opening of the new Reichstag session on 21 March in Potsdam and intended to seal the alliance between Nazis and conservatives.

The elections and the coordination of the federal states had shifted the balance of power in the cabinet in Hitler’s favour. He was now in a position to appoint a further Nazi minister. On 11 March the cabinet agreed to establish a Reich Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, and, on 15 March, having returned from a short trip to Munich, where three days previously he had celebrated the final ‘conquest’ of the city and laid a wreath for ‘the fallen’ at the Feldherrnhalle,75 Hitler was able to congratulate Joseph Goebbels on his appointment as his youngest minister. Originally he had promised him a Ministry of Culture with comprehensive powers, but now Goebbels had to content himself with the fact that the main focus of his work would be state propaganda.76

Hitler supported the establishment of the new ministry by getting the cabinet to give him special powers to transfer a considerable number of responsibilities from other government departments to the new ministry.77 By July, it had acquired its basic structure. The responsibility for radio, hitherto divided between the Postal Ministry, the Interior Ministry, and the states, was assigned to Goebbels and, despite stalling by the states, all regional transmitters now became ‘Reich transmitters’.78 Goebbels took over responsibility for theatres from the Education Ministry (although Göring retained significant power over the Prussian theatres),79 and for fine art and other cultural and media responsibilities from the Interior Ministry.80 Also, despite opposition from the Foreign Ministry, he was able to establish his own foreign department.81

Among other personnel changes that strengthened the Nazi element in the government were Hitler’s replacement on 17 March of Hans Luther as president of the Reichsbank with Hjalmar Schacht, and the appointment at the end of March of Konstantin Hierl as state secretary in the Reich Ministry of Labour and head of the state Labour Service (despite opposition from Labour Minister, Seldte). Fritz Reinhardt, the head of the NSDAP’s ‘Speakers’ School’, was made state secretary in the Reich Finance Ministry at the beginning of April.82

On 21 March, on the occasion of the opening of the Reichstag, the alliance between Nazis and conservatives, between the ‘nationalist revolution’ and Prussian tradition, was to be celebrated with pomp and ceremony in Potsdam.83 On 2 March, at Papen’s suggestion, the cabinet had decided on the Garrison Church as the venue for the occasion, a choice full of symbolism. It contained the tombs of two Prussian kings, Fredrick William I and Frederick II [the Great], and up until the end of the First World War enemy flags and banners captured by the Prussian army were kept there. After a few pious qualms, the Reich President had agreed, but secured himself the main role in the ceremony, which was now clearly designed to resemble the opening of the first ever Reichstag by Kaiser William I.84

Potsdam Day is often described as the Nazis’ first great propaganda success, for they succeeded in shamelessly and hypocritically appropriating Prussian traditions so revered by Germans. Looked at more closely, the occasion has rather the appearance of a demonstration of conservative Germany. With Potsdam a sea of black-white-red flags and hundreds of thousands there primarily to cheer the Reich President, the Nazis were in danger of being downgraded to mere assistants in the restoration of the monarchy.85 Moreover, Hitler’s lack of control of the event was rubbed in by the friendly invitation from the representative of the Catholic Church in Potsdam to attend the service inaugurating the event and thereby demonstrate his oft-expressed ‘belief in God and Christianity’.86 This prompted Hitler and Goebbels, the day before it started, to try to put a stop to all this. Instead of attending the church service, they decided to make a demonstrative visit to the graves of members of the SA buried in the Luise cemetery in Berlin. They justified their absence by claiming that leaders and supporters of the NSDAP had been accused of being ‘apostates’ by representatives of the Church and excluded from the sacraments, a claim that was immediately rejected as an inaccurate generalization.87

Hitler and Goebbels arrived on time for the start of the state ceremony at 12 noon. The Reichstag deputies from the Nazi and bourgeois parties were all assembled in the church; the Social Democrats had declined to participate. Apart from the deputies, the church, which could hold around 2,000 people, was mainly filled with representatives of ‘nationalist’ Germany, including many wearing the colourful uniforms of the old army. After a few words, the Reich President called on Hitler to speak. Hitler praised the recent election result as the expression of a ‘marriage . . . between the symbols of the greatness of the olden days and the vigour of youth’. The handshake between Hindenburg in his field-marshal’s uniform and Hitler in his civilian tailcoat represented the high point of the ceremony.

After laying wreaths on the tombs of the Prussian kings in the crypt, Hindenburg took the salute at a parade of Reichswehr, police, and the ‘nationalist leagues’ (SA, SS, Hitler Youth, and Stahlhelm) lasting several hours, while Hitler and his cabinet were obliged to watch the march past from the second row. The photograph of Hitler taking his leave of Hindenburg with a reverential bow, as carried in the media – Goebbels’s first major coup as Propaganda Minister – became the iconic image of the day. It was intended to symbolize the alliance between the Nazis and the conservative elites. However, two days later, Hitler rejected the restoration of the monarchy, towards which the conservatives had clearly been moving; he declared that, given the misery of the masses, the government considered the issue ‘inappropriate for discussion at the present time’.88

Immediately after the Potsdam ceremony the government ministers agreed further emergency powers. An emergency decree imposed severe penalties for ‘malicious attacks’ on the government (even the death penalty in particularly serious cases). Special courts were set up, intended to ensure the rapid sentencing of offences against both this decree and the Reichstag Fire Decree.89

Two days later, the Enabling Law was on the Reichstag’s agenda. This law, which the cabinet had been discussing for several weeks, envisaged the Reich government being able to pass laws without the participation of parliament, and the Chancellor rather than the Reich President being responsible for the final approval of laws.90 The government was also expressly authorized to issue legislation contrary to the constitution, provided it did not affect the Reichstag and the Reichsrat as institutions or the ‘rights of the Reich President’. With this fine distinction between the two legislatures and the Presidency – the office of Reich President, including the method of election and the position of deputy, was no longer guaranteed – the first step was being taken towards an unconstitutional settlement of the succession to the Reich Presidency in the event of Hindenburg’s death. The law was intended to last for four years, but would become invalid ‘if the present Reich government is replaced by another’. In other words, it was the Hitler/Hugenberg coalition government that was being ‘enabled’; in the event of the government being replaced, the Reich President could insist on the Enabling Law being suspended. He could achieve this through his right to appoint the Chancellor and the ministers. Thus, in principle, the Enabling Law had a built-in guarantee against an unbridled extension of Hitler’s power at the expense of his conservative partners.91 However, it freed him from any kind of parliamentary control. For although, since the recent elections, the government had a majority, he had no intention of subjecting himself to the day-to-day tedium of parliamentary majority government and having to take account of the particular interests of conservative deputies on each issue as it arose. Thanks to his majority, the Chancellor was also no longer dependent on the Reich President’s power to issue emergency decrees. As a result, Hindenburg’s authority, on which the conservatives had based their efforts ‘to contain’ Hitler, was inevitably weakened.

However, the law had not yet been passed. To achieve the requisite two-thirds majority, a change in the procedural rules decreed that those communist deputies who were in prison, had fled, or gone underground should be regarded as non-existent, with the result that the quorum required for the chamber to take decisions was reduced.92 Nevertheless, the support of the Centre Party was still required for the law to pass. To secure this, on 20 and 21 March Hitler made oral promises to the chairman of the Centre, Ludwig Kaas, which he reiterated in the government declaration to the Reichstag on 23 March. They included a guarantee to maintain the federal states in their present form and – with qualifications – for all ‘those elements positively disposed towards the state’ a guarantee of the rights of the religious confessions, of the civil service, and of the Reich President.93

At the Reichstag session on 23 March, which because of the fire was held in the Kroll Opera House, Hitler appeared not in a suit but in his brown Party uniform. At the start of his speech, he expatiated once more on the ‘decline’ that the German people had allegedly suffered during the previous fourteen years, going on to put forward a ‘programme for the reconstruction of nation and Reich’. This proposed law was designed to serve the goal of furthering the ‘welfare of our local authorities and states’, by allowing the government to achieve, ‘from now onwards and for ever after, a consistency of political goals throughout the Reich and the states’. The Reich government wanted to put a stop to the ‘total devaluation of the legislative bodies’ as a result of frequent elections, with ‘the aim of ensuring that, once the nation’s will has been expressed, it will produce uniform results throughout the Reich and the states’.

Hitler announced that ‘with the political decontamination of our public life . . . [would come] a thorough moral purging of the national body’ and praised the two Christian confessions as ‘the most important factors for the maintenance of our nation’. Then he moved to conciliate the Centre Party and to calm fears that the National Socialists intended to attack the Churches. As requested by the Centre Party, Hitler conceded that the ‘judges are irremovable’, at the same time issuing an unambiguous warning that they must ‘demonstrate flexibility in adjusting their verdicts to the benefit of society’. His economic policy announcements remained vague. He talked about ‘the encouragement of private initiative’ and the ‘recognition of private property’ as well as of the simplification and reduction of the burden of taxation. They were going to ‘rescue the German peasantry’, ‘integrate the army of unemployed in the production process’, and protect the self-employed.

In the foreign policy section of his speech Hitler emphasized the government’s willingness to disarm and to seek peace and friendly relations. The Reich government aimed to do everything possible ‘to bring the four great powers, England, France, Italy, and Germany’, closer together and was also willing to establish ‘friendly and mutually beneficial relations’ with the Soviet Union (the persecution of communists was a purely domestic matter for the Reich). However, any attempt to divide nations into victors and vanquished would remove any basis for an ‘understanding’. Finally, Hitler gave the commitments agreed with the Centre Party, while stating that the government ‘insisted’ on the law being passed. As far as its application was concerned, while ‘the number of cases . . . would be limited’, the cabinet would regard ‘rejection’ as a ‘declaration of resistance’.94

Despite the intimidating atmosphere in the hall (which was decorated with swastikas and dominated by SA men), the SPD leader, Otto Wels, while welcoming in his response the foreign policy section of the government statement, nevertheless announced that the SPD opposed the draft bill, and concluded by declaring his commitment to basic human rights and justice, to freedom, and to socialism. Hitler then embarked on an apparently spontaneous ‘settling of accounts’ with Wels, although in fact it was well prepared, as he had already seen a copy of Wels’s speech. Accompanied by thunderous applause from the Nazi deputies, Hitler brusquely rejected Wels’s positive response to the regime’s foreign policy plans. Indicating his contempt for democratic procedures and legality, he made it clear that the Reichstag deputies were simply being requested ‘to agree to something that we could have done anyway’. He, Hitler, would not ‘make the mistake of simply irritating opponents instead of either destroying or reconciling them’. He did not want the SPD to vote for the law: ‘Germany must become free, but not thanks to you!’95

Ludwig Kaas of the Centre Party and the representatives of the BVP, the Staatspartei, and the Christlich-Sozialer Volksdienst [Christian Social People’s Service] then declared their groups’ support for the Enabling Law. When the final vote was taken, there were 94 SPD votes against; the remainder of their total of 120 deputies had either emigrated, were in protective custody, or had excused themselves for reasons of personal security. The overwhelming majority of 444 deputies voted for the law.

The mass arrests of political opponents had begun immediately after the Reichstag fire and increased significantly after the election of 5 March. In addition, from the beginning of March, the SA imprisoned thousands of people, mainly supporters of the left-wing parties, in cellars and provisional camps, of which there were several hundred scattered throughout the Reich, where they were held for months and often tortured.96 Moreover, since the Reichstag Fire Decree, the police had been able arbitrarily to impose ‘protective custody’ on presumed opponents of the regime, without reference to any breach of an existing law, for an indeterminate period, outside judicial control, and without access to legal assistance.97 This extraordinary power in the hands of the security apparatus was to remain the basis of the regime’s system of terror until the end of the Third Reich.

By April 1933, around 50,000 people had been taken into protective custody, albeit many of them only temporarily.98 In spring 1933, some seventy state camps were established to accommodate these prisoners, including in workhouses and similar institutions for ‘asocials’, as well as around thirty special sections in prisons and remand prisons.99 From March onwards, the following camps established along these lines included: Dachau, Oranienburg (near Berlin), Sonnenburg (near Küstrin), Heuberg (Württemberg), Hohnstein (Saxony), and Osthofen (near Worms). In spring 1933 the foundations of the later system of concentration camps were being laid.

Stage 4: Exclusion and coordination

Through the Enabling Law, Hitler had, by the end of March, done much of what was needed to give him a monopoly of power. He rounded off this stage with the elimination of the trade unions and the SPD and the dissolution of the bourgeois parties. But before that happened the NSDAP wished to present itself on 1 May as a party representing the whole nation. Thus, in April, the Party leadership was confronted with the need to control three contradictory developments. The activism of the Party rank and file must not be allowed to flag; the violence must not, however, be permitted to get out of hand; the anti-capitalist ambitions of the Party’s rank and file, which had emerged during March, would have to be directed into safe channels. For there had been numerous cases of ‘interference in business’, particularly at the beginning of March, and they were no longer confined to ‘Jewish’ businesses, but were affecting banks, chambers of commerce, and firms of all descriptions, and, despite bans, kept recurring. They were causing growing concern to conservative politicians and leading business figures and had prompted numerous complaints to the government. The Party leadership needed to put an end to these excesses once and for all.100 Moreover, during March and April there were complaints about the harassment of foreign diplomats and assaults on and the arbitrary imprisonment of foreigners, above all by members of the SA.101

A way out of this situation was provided by a revival of anti-Jewish initiatives, but this time authorized and controlled from ‘above’. The NSDAP had been aiming to reduce the economic influence of Jews for a long time and, since the end of the 1920s, boycotts of Jewish businesses had been routine for many local branches.102 Many Party activists considered it obvious that the ‘seizure of power’ should lead to an increase in such actions. By combining the continuing attacks on Jewish businesses with the ongoing harassment of Jewish lawyers in a joint campaign tolerated by the government, Hitler could present himself as a politician responding to the anti-Semitic demands of the Party activists, while controlling their aggression. In this way the Nazi leadership hoped to create a ‘mood’ conducive to the introduction of anti-Semitic legislation, while at the same time silencing the growing foreign criticism of the new regime’s arbitrary measures. The German Jews were to be used as hostages in order to put a stop to international ‘atrocity propaganda’ (soon termed ‘Jewish atrocity propaganda’ by the NSDAP).

At the end of March, Hitler and Goebbels, who had been summoned to Berchtesgaden to discuss the matter, decided on a boycott of German Jews.103 A ‘Central Committee for the Rejection of Jewish Atrocity and Boycott Propaganda’ was set up, chaired by the Franconian Gauleiter and notorious anti-Semite, Julius Streicher.104 On 28 March, it announced a boycott, expressly authorized by Hitler and the cabinet,105 starting on 1 April.106 To keep matters under control and in order to take account of the concerns of conservatives about potential damage to German exports, on the evening of 31 March, Goebbels announced that the boycott would be ‘suspended’ from the evening of the first day, a Saturday, until the following Wednesday, and only revived if the ‘foreign atrocity propaganda’ continued.107

The official boycott turned out to be very similar to the ‘wild’, that is, unauthorized, actions carried out by Party activists in March: SA and Hitler Youth stood outside stores that had been marked as Jewish and tried to stop customers from entering. Soon crowds of people formed in the shopping districts and most shops closed during the course of the day. There were a number of brave people who deliberately shopped in Jewish shops, but the majority of the population behaved as the regime expected: they avoided the shops.108 That evening, as planned, the boycott was suspended, with the Committee declaring it a success, as the hostile ‘atrocity propaganda’ had largely ceased.109 In fact, the regime had managed to persuade a number of Jewish organizations and individuals to call for an end to foreign boycotts of German goods.

The Party activists, however, continued with their campaign against Jewish lawyers and the judicial authorities responded by transferring or suspending Jewish judges and prosecutors and introducing quotas for Jewish attorneys.110 At this point, as anticipated, the regime intervened, in effect legalizing these measures. The Law for the Re-establishment of a Professional Civil Service of 7 April decreed that those public servants ‘who are not of Aryan descent’ were to be retired. Following an intervention by Hindenburg, civil servants who had been in post before 1 August 1914, who had fought at the front, or whose fathers or sons had been killed in the war were exempted from this regulation.111 During the following months around half of the 5,000 Jewish civil servants lost their jobs.112 The Law concerning the Admission of Attorneys, also issued on 7 April, banned attorneys ‘not of Aryan descent’ from practising, with the same exemptions as contained in the Professional Civil Service Law.113 During the following months, similar bans were introduced for other state-approved professions, such as patent lawyers and tax advisers. The Law against the Overcrowding of German Schools and Colleges issued on 25 April limited the number of Jewish pupils and students,114 while Jewish doctors and dentists were excluded from the health insurance system.115 More ambitious plans to prevent Jewish doctors from practising at all were initially blocked by Hitler, who told the Cabinet that ‘at the moment’ such measures were ‘not yet necessary’,116 clear proof of the extent to which the Chancellor controlled policy detail during these weeks.

The Professional Civil Service Law broke with the principle of the legal equality of Jews throughout the German Reich for the first time since its foundation in 1871. In the past, Hitler’s conservative coalition partners had always rejected the idea of revising Jewish emancipation, so their acceptance of this step represented an important moral victory for the National Socialists over their ‘partners’. But that was not the only point. For the Professional Civil Service Law not only brought about the dismissal of Jewish civil servants, but also paved the way for a large scale ‘purge’ of the civil service, thereby effectively removing the privileged status of German officials with their ‘traditional rights and responsibilities’ and contributing to a disciplining of the state apparatus. Approximately 2 per cent of the civil service was affected by the provisions of the law, which included dismissal on political grounds, but also demotion and premature retirement.117

At the end of March, a Reich law transferred the right to legislate in the federal states from parliaments to governments, while the number of each party’s deputies in the state parliaments was adjusted in accordance with the results of the Reichstag election of 5 March (with the communist vote being ignored); the local councils were also reorganized on the basis of the 5 March election.118 Under the Second Law for the Co-ordination of the Federal States of 7 April Reich Governors (Reichsstatthalter) were appointed to the states with the power of appointing the state governments.119 This meant that the hitherto lauded autonomy of the states had been finally removed. The first Reich governor to be appointed by Interior Minister Frick on 10 April was Ritter von Epp in Bavaria. In the meantime, Epp had created a provisional Bavarian government composed of Nazis and his rapid appointment suggests that Hitler wanted to prevent Bavaria from becoming too strong a power base for the Party; Epp was not a member of the local Party clique. In the other states the Gauleiters were appointed Reich Governors; they now exercised control over the state governments in the name of the Reich government, assuming they had not already become prime minister of their state. This meant that those states in which the NSDAP could never have achieved a majority were now also firmly in the hands of the Party. Hitler’s conservative coalition partners, on the other hand, had been left empty-handed with nothing to say in all these federal states, each of which had substantial administrations carrying out important functions.120

In Prussia Hitler took over the responsibilities of governor himself, which meant that Papen’s post as ‘Reich Commissar’ in Prussia had ceased to exist and so another element in the ‘taming concept’ had proved useless. On 11 April, Hitler appointed Göring (and not Papen) prime minister of Prussia (after Göring had indicated that he was going to get the Prussian parliament to elect him prime minister). Göring kept the office of Prussian interior minister and, on 25 April, Hitler also transferred to him the responsibilities of Reich governor. With the appointment of the acting Nazi Reich Commissars, Hanns Kerrl as Prussian Minister of Justice and Bernhard Rust as Prussian Minister of Culture, Göring had created in Prussia another power base that was firmly in National Socialist hands. Significantly, he had no intention of appointing Reich Commissar Hugenberg to the Prussian ministries of Agriculture and Economics.121

In April the Nazis also had considerable success in coordinating associations. Initially, this involved primarily economic associations. Among the extremely woolly economic ideas held by various Nazis before 1933, the notion of a ‘corporatist state’ [Ständestaat] had been particularly prominent. The idea was that in a future Third Reich the individual ‘professions/occupations’ [Stände] would to a large extent regulate their own affairs in professional organizations, thereby bridging the conflicts of interest between capital and labour, regulating the markets, and preventing domination by large industrial firms.122

During the first months after the take-over of power, the representatives of the self-employed within the NSDAP, organized in the Combat League for the Commercial Middle Class, set about trying to realize this idea.123 At the beginning of May, commerce and the artisanal trades were formed into separate ‘Reich groups’ and Adrian von Renteln, the leader of the Combat League, took over the leadership of the new artisanal trades’ organization.124 The representatives of the self-employed saw it as an initial victory when the cabinet introduced a special tax for department stores and chain stores, banned department stores and chain stores from having artisan shops such as hairdressers, and forbade the opening of new chain stores.125

To begin with, the Reich Association of German Industry’s (RDI) response was guarded. On 24 March, under massive pressure from Fritz Thyssen, it declared its support for the government. However, in a memorandum, released simultaneously, it made clear its intention of sticking to its basic policy of economic liberalism.126 On 1 April, the day of the Jewish boycott, Otto Wagener turned up at the RDI’s offices demanding changes to its board. Wagener was the former head of the NSDAP’s economic department and, after the seizure of power, had established his own section, dealing with economic policy, within the Party’s Berlin liaison office.127 He insisted that the general manager, Ludwig Kastl, was unacceptable on political grounds, that several Jewish members should leave, and that a number of people should be appointed whom the NSDAP could rely on to ‘coordinate’ the RDI’s activities with government policy. All attempts by the industrialists to get access to Hitler to persuade him to withdraw these demands proved unsuccessful. Meanwhile, on 24 April, in an attempt to maintain his influence, Hugenberg appointed Wagener and Alfred Moeller, a DNVP supporter, Reich Commissars for the RDI and for the economy generally (apart from agriculture). The RDI acceded to Wagener’s demands, reorganized its board in accordance with the Führer principle and finally, on 22 May, dissolved itself. Then, just over a month later, it amalgamated with the Association of German Employers’ Organizations to form the Reichsstand der Deutschen Industrie. The new name paid lip service to the ständisch [corporatist] line of the Nazi economic reformers; but the fact that the old chairman of the RDI, Krupp, was also chairman of the new organization indicated the continuity that existed between the two organizations.128

In the agricultural sphere Hugenberg had initially concentrated on raising prices through higher tariffs and by intervening in food production, and also on protecting agriculture with state subsidies and the prevention of foreclosures. These measures represented the most important points on the cabinet’s agenda since the start of the year;129 they were pushed through by Hugenberg, in some cases against Hitler’s wishes, who often made detailed comments at meetings on agricultural issues.130 Moreover, on 5 April, the Chancellor defended this policy in a speech to the German Agricultural Council, the umbrella organization of the Chambers of Agriculture, despite the fact that it was against the interests of consumers and creditors, and threatened the export-oriented manufacturing industries. According to Hitler, it was the peasants who secured ‘the nation’s future’.131

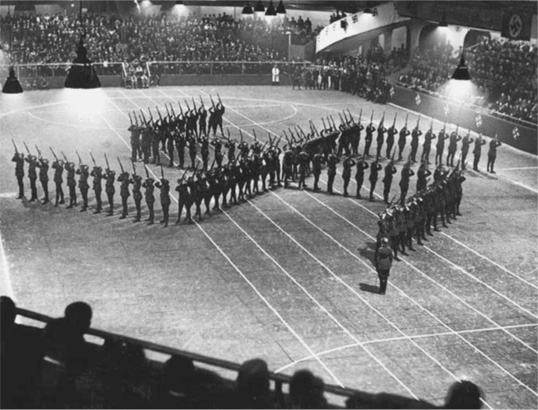

Figure 3. The executive committee of the Berlin Police used the force’s ninth indoor games on 17 March 1933 to put on a show of loyalty to the new regime. This photo shows the ‘Friedrich Karl’ division of the Prussian state police, rifles raised, in a swastika formation. The Nazi emblem was displayed throughout the Berlin Sportpalast.

Source: Scherl/Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo

However, in the meantime, Richard Walther Darré, the leader of the Nazi Party’s agricultural department, had begun coordinating all the agricultural organizations one after the other, thereby undermining Hugenberg’s position as Agriculture Minister.132 In contrast to Hugenberg’s policy of concentrating on protecting agrarian economic interests, Darré’s policy was dominated by the ideology of ‘blood and soil’, which aimed at subordinating the agrarian economy as an ‘estate’ [Stand] to an ‘ethnic political’ conception, and transforming the whole agricultural sector into a compulsory cartel. In May 1933, despite the opposition of Hugenberg as acting Prussian Agriculture Minister, he succeeded in pushing through an ‘hereditary farm law’ for Prussia, subjecting farms to permanent entailment, preventing their division or sale, and tying the hereditary farmer’s family to that particular piece of land. This provided the model for later entailment legislation applying to the Reich as a whole.133 With his appointment as Reich Minister of Food at the end of June, Darré was finally able to get the better of Hugenberg, who had become increasingly isolated in the cabinet as a result of his one-sided agricultural policies and for other reasons that will be dealt with later.134

Apart from coordinating the leading economic associations, the Nazis placed great emphasis on gaining control of every kind of club and association. To start with, the workers’ associations were crippled by the elimination of the SPD and KPD and then later formally closed down. The numerous and locally diverse artisan associations135 were also subjected to this process, as were sports and youth clubs. The sports clubs were reorganized by SA leader Hans von Tschammer und Osten, who was appointed Reich Sports Commissar on 28 April and finally, on 19 July, Reich Sports Leader.136 The Hitler Youth leader, Baldur von Schirach, took control of the Reich Committee of German Youth Associations, which represented some five to six million young people. On 5 April 1933, he ordered a Hitler Youth squad to occupy its offices and took over the management. On 17 June, Hitler appointed Schirach Youth Leader of the German Reich and, through this new office, authorized him to supervise all work relating to young people. On the day of his appointment, Schirach ordered the closure of the Grossdeutscher Jugendbund [Greater German Youth Association], to which most members of the bündisch youth movement were affiliated.† As a result of the integration of numerous youth organizations and the huge increase in new members, both boys and girls, between the beginning of 1933 and the end of 1934 the membership of the Hitler Youth (HJ) went up from around 108,000 to 3.5 million. Around half of young Germans aged between 10 and 18 were now in Nazi organizations as ‘cubs’ (Pimpfe), young lasses ( Jungmädel), Hitler Boys (Hitlerjungen), or ‘lasses’ (Mädel).137

In the end, every form of club and association, whether it was the volunteer fire brigades, stamp collectors, rabbit breeders, or choral societies, was caught up in this process of ‘coordination’; every single association was forced to submit to the Nazis’ demand for total control. In these associations millions of Germans came together in order to follow the most diverse economic, cultural, and social pursuits and to organize their spare time in their own way. The regime was determined to prevent any possibility of such associations providing a future forum for criticism or opposition; opportunities for the formation of public opinion outside the parameters established by the regime and the Party were to be blocked right from the start. The associations were obliged to subordinate themselves to Nazi-dominated umbrella organizations, to alter their statutes in order to replace a committee structure with the Führer principle, to ensure that people who were objectionable in the eyes of the local Party were excluded, that Nazis were appointed to leading positions, and finally to introduce the so-called ‘Aryan clause’ banning Jews from membership.138 In many cases the associations were only too happy to adapt to the new circumstances and hurried to conform, whereas in others the process took until the following year or even longer to complete. Many middle-class associations appear to have been hesitant in responding to the demands of the new order and to have only superficially conformed to Nazi requirements, with the old life of the association continuing broadly unchanged. Thus, in reality, it was impossible for the Party to establish total control over every club, society, or association.139

The coordination of associations and interventions in business occurred alongside massive Nazi attacks on the DNVP and the Stahlhelm. In cabinet too Hitler’s tone, which had initially been conciliatory, became increasingly authoritarian and uncompromising, and he sought to avoid lengthy discussion of technical issues.140 Both within and outside the government, the Nazis increasingly turned against the bourgeois-nationalist milieu they considered ‘reactionary’.

From the beginning of April, a growing number of complaints reached DNVP headquarters about attacks by members of the NSDAP on the DNVP and its organizations. Hugenberg frequently complained about the attacks to Hitler and the Reich President, but almost invariably to no effect.141 His performance as a multiple minister was also subjected to ferocious criticism in the Nazi press. On 20 April, Hitler’s birthday, he published a newspaper article, pointing out that the use of the Enabling Law depended on the continuing existence of the coalition and complaining about ‘unauthorized personnel changes in economic organizations and public bodies’. This, together with a similar complaint from Reich Bank president, Schacht, did in fact lead to an order from Hitler to the Party organization, issued via its Berlin liaison staff, to refrain in future from unauthorized interference in business.142 This, however, did not affect the continuing attacks on the members and organizations of the DNVP.143

During February and March, there had also already been repeated attacks by SA men on members of the Stahlhelm. At the end of March, the Brunswick interior minister had even banned the local Stahlhelm on the grounds that the organization was being infiltrated by former members of the [largely socialist] Reichsbanner.144 In view of the growing pressure, by the beginning of April, the leader of the Stahlhelm, Franz Seldte, had already decided to subordinate himself to Hitler and abandon his organization’s independence. On 28 April, he finally dismissed his deputy, Theodor Duesterberg (who was being criticized by the Nazis for his doubts about the formation of the Hitler government and because his wife was Jewish), and the following day declared that he was subordinating himself and the Stahlhelm to Hitler.145

The process of coordination was in full swing on 20 April, Hitler’s 44th birthday, which was celebrated as though it were a public holiday. Many private houses as well as public buildings had put up flags and were decorated with flowers. Throughout the Reich, church services, marches, and torchlight processions were held to mark the day. Radio programmes were entirely geared to the event. ‘The whole German nation is celebrating Adolf Hitler’s birthday in a dignified and simple way’, reported the Völkischer Beobachter,146 and the non-Nazi press joined in the praise almost without reservation.147 In numerous places Hitler had been made an honorary citizen and streets had been named after him; a regular kitsch industry had sprung up, offering a broad range of devotional items dedicated to Hitler.148 However, this picture of a nation united behind the ‘Führer’ was dramatically contradicted by the numerous conflicts that characterized the domestic political situation in spring 1933. The orgy of celebration around Hitler’s birthday tells us much more about the propaganda apparatus that was being constructed, which had fastened on the Hitler cult as a central element, than it does about ordinary people’s real attitude to their new ‘people’s chancellor’.