16

Becoming Sole Dictator

Hitler’s increasing influence on foreign policy before spring 1934 resulted, above all, in the Third Reich becoming more and more diplomatically isolated while, at the same time, serious problems were emerging in domestic politics. The series of propaganda campaigns and major events with which the regime had swamped Germany during its first year in order to demonstrate to the outside world how united the nation was proved less and less capable during its second year of disguising the very real problems that existed.

To start with, there was the problem of the SA. After Hitler’s refusal in July 1933 to continue the Nazi ‘revolution’, the conflict between the Party leadership and the SA, which had run through the Party’s history since 1923, continued. Initially, Röhm pursued a strategy of expanding the membership from 500,000 men at the beginning of 1933 to over four and a half million in mid-1934; this was achieved by admitting new members and integrating other coordinated paramilitary organizations. Röhm believed that the sheer weight of this mass organization would guarantee his SA a powerful position in the Nazi state.1 During the months after the seizure of power, he had tried to secure a decisive influence over the state administration, particularly in Bavaria, by appointing SA special commissioners. However, by the autumn of 1933, this attempt had clearly failed. The SA auxiliary police had been dismissed,2 and the SA had not managed to maintain its role in supplying concentration camp guards.3 In addition, Röhm had attempted to transform the SA into a popular militia and, initially, during 1933, had in fact succeeded in integrating it into the Reichswehr’s rearmament plans. However, during the autumn of 1933, it became apparent, as has been described above, that Hitler and the Reichswehr leadership were moving towards adopting another model for the Reichswehr’s development. The Reichswehr was to become a conscript army, with the SA responsible only for pre-military training and for maintaining the military effectiveness of reservists.4

At the same time, Hitler cautiously, and without seeking a confrontation with Röhm, set about limiting the role of the SA elsewhere. At the end of 1933, he began to extend his control over the whole of the Nazi movement, and to ‘integrate’ the entire Party organization into the state apparatus, with the aim of further strengthening his own position.

On 21 April 1933, Hitler had already appointed Hess, who, since December 1932 had been head of the Political Commission of the NSDAP, to be his deputy for Party affairs, giving him authority ‘to take decisions in my name in all matters involving the Party headquarters’;5 on 1 September 1933, he gave him the title ‘Deputy Führer’.6 After this initial regulation of internal Party matters, on 1 December 1933, the Law for securing the Unity of Party and State was enacted, which stated that the NSDAP was the ‘bearer of the concept of the German state and is indissolubly linked to the state’. The Party was made an ‘official body under public law’, which represented a promotion from its previous status as a ‘registered association’, but still subordinated it to state law. However, the members were subjected to a special Party judicial system, which in theory was entitled to order ‘arrest and detention’. In practice, however, it never came to what would have been a breach in the state’s monopoly of the penal code; instead, there were disciplinary measures such as expulsion from the Party.7 Moreover, Hitler used this law to appoint two more Nazi ministers: Rudolf Hess, the ‘Führer’s’ Deputy, and Ernst Röhm, the chief of staff of the SA, became ministers without portfolio. All these measures had the effect of integrating the Party into the state rather than, as many Party functionaries had been anticipating,8 enabling the Party to dictate to the state. During this period, Goebbels repeatedly recorded this as being Hitler’s intention.9 However, the ‘Führer’ deliberately left open the question of how he was going to regulate the relationship between Party and state over the longer term.

The appointment of Röhm as a Reich minister was also intended as compensation for the decline in his real power. However, he did not accept this basic presupposition behind his promotion; instead, he responded to his appointment by announcing that the SA was now integrated through ‘my person into the state apparatus’ and ‘later developments will determine’ ‘what spheres of operation’ may be acquired in the future.10 In fact, he stepped up his attempt to turn the SA into an entirely independent organization, by trying to create a kind of state within the state. He set up a separate SA press office; he maintained foreign contacts,11 for which he even established a special ‘ministerial office’; he attempted to influence higher education policy; and there were even signs of the emergence of an ‘SA legal code’ with its own norms.12

Röhm had good reason to do what he could to offer his people hope for the future. For the SA was an exceptionally heterogeneous mass body and, as a result of having expanded through integrating a range of different organizations, had a very unstable structure; discontent and lack of discipline were rife. Most of the ‘old fighters’, who had often suffered a loss of social status as a result of the economic crisis, still had few prospects of employment and now saw themselves being cheated out of a reward for their years of commitment to and sacrifices for the Party. At the same time, the masses of new members were having to face the fact that, despite their support for the movement, their position had not improved overnight. The SA men’s frustration was being expressed in numerous excesses and acts of violence, which, since all their political enemies had been crushed, were often directed at the general population.13 At the turn of the year 1933/34, Röhm once again publicly asserted his old claim for the primacy of the soldier over the politician and confidently demanded the completion of the National Socialist revolution; his aim was, in part at least, to provide an outlet for this pent-up frustration.14

Hitler responded by once more proclaiming the end of the revolution and the preeminence of the Party. All the greetings telegrams he sent on 31 December to Röhm, Hess, Göring, Goebbels, and other Party bigwigs referred to ‘the end of the year of National Socialist revolution’.15 He was equally unequivocal when he spoke to the SA leadership, assembled in the Reich Chancellery on 22 January 1934, of the ‘increasingly strong position of the Party as the commanding representative and guarantor of the new political order in Germany’.16 And, at the same time, Hess was warning the organization in a newspaper article not to ‘go its own way’.17 Hitler’s appointment of Alfred Rosenberg, on 24 January, to be responsible for ‘supervising the entire intellectual and ideological indoctrination and education of the NSDAP’ can be seen as not only strengthening the dogmatic-völkisch elements in the NSDAP, but also as an additional means of tightening up the whole of the Party’s operations.18

Church policy

Apart from the conflict with the SA, the disputes within the Protestant Church were reaching a climax in the autumn and winter of 1933. It was becoming clear that Hitler’s unwillingness to give further support to the German Christians (that was the implication of his declaration of neutrality on the Church question, made to the Gauleiters on 5 August 1933) in the longer term was undermining their dominant position within the Church.

On 6 September 1933, the General Synod of the Protestant Church of the Old Prussian Union, dominated by the German Christians, issued a Church law according to which, in future, all clergy and Church officials had to prove that they were of ‘Aryan descent’.19 This immediately prompted Martin Niemöller and Dietrich Bonhoeffer to set up a Pastors’ Emergency League. This became the core of an opposition movement within the Church to resist the German Christians’ ruthless use of their majorities within Church bodies to introduce Nazi ideology into the Church. Hitler’s ambivalent attitude to the Protestant Church had enabled such an internal opposition to emerge, and in fact it suited him. For although he had wanted a unified Protestant Church in order to use it as a counterweight to Catholicism, he regarded both Churches in the longer term as ideological competitors. Thus, it was entirely in his interest for them to be weakened by internal splits. The Emergency League, of which, in January 1934, more than a third of pastors were members,20 kept stressing its basic loyalty to the Hitler regime. Thus, in a telegram sent to ‘our Führer’ on 15 October, on the occasion of Germany’s departure from the League of Nations, it pledged its ‘loyalty and prayerful solicitude’.21

On 13 November, the German Christians organized a major event in the Sportpalast. There was a scandal when one of the speakers, the Gau chief of the Berlin German Christians, Reinhold Krause, publicly expounded völkisch religious principles. Also, the audience of 20,000 passed a resolution in which, among other things, they distanced themselves from the ‘Old Testament and its Jewish morality’, demanding a ‘militant and truly völkisch Church’, which alone would ‘reflect the National Socialist state’s claim to total domination’.22 The Pastors’ Emergency League then sent an ultimatum to Bishop Müller demanding that he publicly distance himself from this gross abandonment of the core principles of Christian belief. There was the threat of a split in the Church. Müller responded by stripping Krause of all his Church functions,23 suspending the Church’s ‘Aryan clause’, and reshuffling the Reich Church’s governing body, with German Christians in future being banned by Church law from membership of it.24 At the end of November, Hitler informed Müller in the course of a private conversation that he had no intention of intervening in the Church conflict, announcing this publicly in the Völkischer Beobachter.25 On 8 December, Goebbels noted in his diary that Hitler had ‘seen through . . . the unctuous parsons and Reich Bishop Müller’. Krause was ‘the most decent of them’. He ‘at least [had made] no bones about his contempt for the Jewish swindle of the Old Testament’.26

On 20 December, off his own bat, Müller ordered the integration of the Evangelisches Jugendwerk [Protestant Youth Organization] into the Hitler Youth. It was the umbrella organization for the Protestant Church’s youth work with a membership of around 700,000. Müller, however, was wrong in his assumption that this would win back Hitler’s trust. For, annoyed by the situation in the Protestant Church, for which he himself bore much of the responsibility, Hitler was not even prepared to send the letter of appreciation that Müller had requested.

On 25 January, with the aim of clarifying the whole situation, Hitler, accompanied by Frick, Göring, Hess, and the head of the Interior Ministry’s religious affairs department, Rudolf Buttmann, received a delegation from the Protestant Church composed of German Christians and their opponents. Reich Bishop Müller was present, as was Pastor Niemöller.27 At the meeting Göring, who had used the Gestapo to spy on the Church opposition,28 began by reading out the report of a recording of a telephone conversation Niemöller had had that morning. Niemöller had discovered that, as a result of an intervention by the Church opposition, the Reich President had suddenly summoned his Reich Chancellor on the morning of the 25th. Niemöller had then said on the telephone that Hitler was being given the ‘last rites’ before the meeting with the Church representatives. With this revelation Hitler was able to dominate proceedings right from the start. He took Niemöller to task in front of his colleagues and made further accusations against his visitors during the course of the meeting, forcing them continually to justify themselves. Finally, he ended by appealing to them to cooperate, effectively demanding that the Church representatives should subordinate themselves to his regime.

Hitler’s annoyance at Niemöller’s contemptuous remark was definitely not simply tactically motivated in order to dominate the meeting. It arose from his deeply rooted fear of being humiliated or shamed in front of others, a fear he characteristically tried to overcome by means of a massive attack on Niemöller. Niemöller was now on the list of enemies Hitler intended to destroy. The fact that, a few years later, Hitler had Niemöller incarcerated in a concentration camp as his personal prisoner until the end of his regime was almost certainly largely the result of his disrespectful comment on 25 January, for which Hitler could not forgive him.

Göring’s dossier and Hitler’s appeal to the ‘patriotic sense of responsibility’ of the Church leaders finally persuaded them after the meeting to issue a declaration of loyalty both to Hitler’s regime and to the Reich Bishop.29 The conflict in the Protestant Church was, however, by no means settled.

Party and state

Hitler used his government statement on 30 January 1934, the first anniversary of the seizure of power, above all to settle scores with various regime opponents and other unreliable ‘elements’. However, he did not mention the SA; his criticisms were aimed at a very different target. First, he silenced those who had hoped that his regime would bring about the restoration of the monarchy. The issue of the final constitution of the German Reich was ‘not up for discussion at the present time’. He saw himself as merely the ‘nation’s representative, in charge of implementing the reforms that will eventually enable it to reach a conclusive decision about the German Reich’s final constitutional form’.30 Hitler’s statement had an immediate effect: four days later, the Reich Interior Minister banned all monarchist associations.31

Then, in his speech, Hitler went on to tackle in a highly sarcastic and disdainful manner ‘the numerous enemies’, who had attacked the regime during the past year. Among them were the ‘depraved émigrés’, ‘some of them communist ideologists’, whom they would soon sort out. By the end of 1933, 37,000 Jews and between 16,000 and 19,000 other people – the estimates vary – had emigrated, mainly for political reasons. The majority were communists but there were also around 3,500 trade unionists and Social Democrats, as well as pacifists, liberals, conservatives, and Christians.32 Hitler also attacked members of our ‘bourgeois intelligentsia’, who rejected ‘everything that is healthy’, embracing and encouraging ‘everything that is sick’. A few days earlier in a lengthy interview with the Nazi poet, Hanns Johst, he had violently attacked ‘un-political’ people.33 Relying on the result of the November 1933 ‘election’, Hitler claimed that all these opponents ‘did not even amount to 2.5 million people’. They could not be ‘considered an opposition, for they are a chaotic conglomeration of views and opinions, completely incapable of pursuing a positive common goal, able only to agree on opposition to the current state’. However, more dangerous than these opponents were ‘those political migrant birds, who always appear when it’s harvest time’, ‘who are great at jumping on the bandwagon’, ‘parasites’, who had to be removed from the state and the Party.

Thus, according to Hitler, apart from the communists who had survived the persecution of the first year of the regime, there was a diffuse agglomeration of opponents, people standing on the sidelines, and opportunists; they did not pose an existential threat to the regime, but obstructed the development of the Nazi state. He did not mention the fact that there were millions of other people – for example, Social Democrats or Christians of both confessions – who did not support his regime for other reasons. Despite his attempts to ridicule, belittle, and marginalize this combination of opponents and ‘grumblers’, his strained rhetoric betrayed considerable uncertainty. The first anniversary of the seizure of power was by no means a brilliant victory celebration.

In his speech Hitler specifically defended the regime’s policy of taking action against those whose ‘birth, as a result of hereditary predispositions’, had ‘from the outset had a negative impact on völkisch life’, and announced that, after its ‘first assault’ on this phenomenon – the previous summer’s Sterilization Law – his government was intending ‘to adopt truly revolutionary measures’. In this context, he strongly criticized the Churches for their objection to such interventions: ‘It’s not the Churches who have to feed the armies of these unfortunates; it’s the nation that has to do it.’

Following this speech, the Reichstag adopted the Law concerning the Reconstruction of the Reich, which, among other things, abolished the state parliaments, enabled the Reich government to issue new constitutional law without the need for Reichstag approval, and subordinated the Reich Governors, most of whom were Gauleiters, to the Reich Interior Ministry when performing their state functions.34 This meant that Hitler had succeeded to a large extent in ‘integrating’ the regional Party agencies into the state apparatus. A few days later, on 2 February, he made this crystal clear by telling a meeting of Gauleiters that the Party’s ‘vital main task’ was ‘to select people, who, on the one hand, had the capacity, and, on the other, were willing to implement the government’s measures with blind obedience’.35

At the end of February, Hitler’s position as absolute leader of the Party was demonstrated in a large-scale symbolic act. On 25 February, Rudolf Hess presided over a ceremony, which was broadcast, in which leaders in the Party’s political organization, and leaders of its ancillary organizations at all levels were assembled throughout the Reich to swear personal allegiance to Hitler; according to the Völkischer Beobachter, it was the greatest oath-taking ceremony in history. On the previous evening, Hitler had given his usual speech in the Munich Hofbräuhaus to commemorate the official founding of the NSDAP fourteen years before, and once again defined the Party’s future function: ‘The movement’s task is to win over Germans to strengthen the power of this state’.36

The subordination of the Reich Governors to the Reich Interior Ministry raised the fundamental question as to whether the Reich Governors were also subordinate to the other Reich departmental ministers. On 22 March, Hitler explained his basic approach in a speech to the Reich Governors in Berlin in which he clarified their ‘political task’: it was not the job of the Reich Governors to represent ‘the states vis-à-vis the Reich , but the Reich vis-à-vis the states’.37 In June 1934, he made his position absolutely clear in a written order. The Reich Party leaders were, in principle, subordinate to the ministries; however, in matters of ‘special political importance’, he would himself decide on disputes between the Governors and ministers. He would also decide whether a matter was ‘of special political importance’. This instance shows how skillfully Hitler exploited the rivalry between the state apparatus and the Party in order to enhance his position as the final arbiter.38

The strengthening of the Reich government in Berlin also served gradually to undermine the Prussian government; this was the only way of preventing a rival government from emerging under Göring. In September 1933, Göring had attempted to raise his status as Prime Minister of Prussia by creating a Prussian State Council; significantly, Hitler had not attended the inauguration. Now Göring was forced to agree to the amalgamation of the Prussian ministries with their Reich counterparts. Thus, in February the Prussian Ministry of Justice was combined with the Reich Justice Ministry; and, on 1 May 1934, Hitler appointed the Prussian Culture Minister, Bernhard Rust, to be Reich Minister of Science, Education, and Further Education, thereby transferring his previous Prussian responsibilities to the Reich. At the same time, he appointed Reich Interior Minister Frick to be Prussian Interior Minister; by November 1934 both ministries had been amalgamated. However, as Prime Minister, Göring continued to be responsible for the Prussian state police, while, even after Himmler had taken over the Gestapo in April 1934, he continued to claim the formal status of ‘chief’ of the Prussian secret police. As compensation for his loss of power in Prussia Göring was put in charge of a new central Reich body, the Reich Forestry Office. Finally, during 1934–35, the personal union of the Reich and Prussian Ministries of Agriculture (Darré) and of Economics (Schacht) was brought to an end with the amalgamation of each of these two sets of ministries.39

More and more ‘grumblers and whingers’

Hitler’s commitment in October 1933 to establish a 300,000-strong army on the basis of conscription for one year, and the measures taken by the Reichswehr during the following two months to put that commitment into effect represented a definite decision against the model of an SA militia, as envisaged by Röhm. Nevertheless, on 1 February, Röhm presented the Defence Minister with a memorandum in which he described the future role of the Reichswehr as a training school for the SA. Blomberg responded by informing a meeting of military commanders that the attempt to achieve an agreement with Röhm had failed and Hitler must now decide between them.40 At the same time, an increasing number of incidents was occurring between members of the Reichswehr and the SA.41

On 2 February, Hitler told the Gauleiters that ‘those who maintained that the revolution was not over’ were ‘fools’42 and, on 21 February, he informed a British visitor, Anthony Eden, that he did not approve of an armed SA. However, on 28 February he went further: he summoned the leadership of the SA and the Reichswehr and spelled out to them the basic outlines of the future military arrangements. He argued that a militia, such as that envisaged by Röhm, was unsuitable as the basis for a new German army. The nation’s future armed force would be the Reichswehr, to be established on the basis of general conscription. The ‘nationalist revolution’, as he made absolutely clear, was over. Immediately after the meeting, Röhm and Blomberg signed an agreement containing the guidelines for future cooperation between the SA and Reichswehr, which involved the subordination of the Party troops to the generals. Röhm had to recognize their sole responsibility for ‘preparing the defence of the Reich’; the SA was left with the pre-military training of young people, the training of those eligible for military service who had not been drafted into the Reichswehr, and a number of other auxiliary services.43

Röhm pretended to accept Hitler’s decision, but at the same time made it very obvious that he was claiming a greater role for his SA within the state. Thus, in a number of widely reported speeches he called the SA the embodiment of the National Socialist revolution, for example in an address to the diplomatic corps on 18 April, which he had published as a pamphlet.44 Moreover, in spring 1934, the SA organized major field exercises and parades,45 and established armed units in the shape of so-called ‘staff guards’, about which Defence Minister Blomberg submitted a written complaint to Hitler at the beginning of March.46 On 20 April, on the occasion of Hitler’s 45th birthday, Röhm issued an order of the day, which could be read as an enthusiastic declaration of loyalty to the ‘Führer’. However, it contained a distinctly provocative sentence: ‘for us political soldiers of the National Socialist revolution’ Hitler ‘embodies Germany’.47 A few days earlier, Hitler had been sailing through Norwegian waters on the battleship ‘Deutschland’, discussing his military plans with Blomberg, Admiral Erich Raeder, and other high-ranking Reichswehr officers.48

In the meantime, the domestic opponents of the SA had been mobilizing. The Nazi Party bosses in the individual states tried to form a counterweight to the growing ambitions of the SA by supporting the SS. They began handing over to Himmler control over their political police departments; indeed, with his take-over of the Prussian Gestapo on 20 April 1934, he had finally become head of a Reich-wide secret police.49 The political police and the Nazi Party’s security service (SD) were collecting material to use against the SA; the same was true of the Reichswehr, at the latest from April 1934 onwards; and, from May 1934, Göring, the SS, and the military appear to have been passing information about the SA to Hitler. Röhm responded by giving instructions in May for evidence to be collected concerning ‘hostile actions’ against the SA.50

This complex power struggle in spring 1934 was occurring at the same time as a serious crisis of confidence was emerging between the regime and the German people, resulting above all from significant socio-economic failures. This provides the background to the escalation in the conflict over the SA during the spring and early summer of 1934.51 The main danger did not arise from the issue on which the regime had been concentrating its efforts since 1933: unemployment. The number of those registered as unemployed had reduced from six million in January 1933 to under 2.8 million in March 1934 and declined further depending on the season. Of the 3.2 million who were no longer recorded in the statistics over a million were employed in various work creation projects.52 However, an important reason for the reduction in the unemployment statistics was that they were being rigged; the regime defined the term ‘unemployed’ in such a way that certain groups of employees no longer appeared in the unemployment insurance statistics.53 Hitler proclaimed the ‘second battle of work’ with the start of the construction of the Munich–Salzburg autobahn on 21 March 1934,54 and the regime highlighted this topic in its socio-political propaganda during the following weeks with some success.55 However, any further positive economic developments had for a long time been under threat from another quarter altogether.

For during 1933–34 German exports had been in continual decline.56 There were various reasons for this. The world economic crisis had led to protectionist trade restrictions, in which Germany had also been involved. Germany’s unilateral debt moratorium in summer 1933 had provoked counter-measures abroad that had further damaged German exports. After the pound and dollar devaluations in autumn 1931 and spring 1933, the Mark became relatively overvalued; however, Schacht and Hitler rejected a devaluation of the Mark because of Germany’s large foreign debt and for fear of inflation.57 The incipient rearmament programme guaranteed the domestic market, diverting attention from attempts to increase exports. The international movement to boycott German goods, a reaction to the regime’s arbitrary and oppressive behaviour and, in particular, the persecution of the Jews, also had a negative impact. At the same time, Germany was heavily dependent on raw material and food imports. As a result, by the beginning of 1934, the Reichsbank’s foreign exchange reserves had been reduced to almost zero. Germans travelling abroad were subjected to drastic foreign currency restrictions.58

While the shortage of foreign exchange prompted renewed fears of inflation, the population was also upset by actual price increases for foodstuffs59 and by shortages.60 The hopes that millions had invested in the promise of a favourable policy for self-employed artisans and retailers were being disappointed;61 peasants felt under pressure from the strict regulations imposed by the Reich Food Estate. Those who had been previously unemployed and had now found employment compared their present situation with that before the crisis and concluded that they had been better off in 1928. The idea that the reduction in unemployment resulted in millions of grateful workers turning to the regime is an exaggeration often found in the literature; there is little evidence for it. On the other hand, there were several developments that can account for the continuing discontent in factories. First, there was the removal of the workers’ rights contained in the Weimar social constitution: works’ councils had been replaced by ‘Councils of Trust’, which only had the right of consultation. Secondly, the Law for the Ordering of National Labour of 20 January 1934 had shifted the balance of power within factories decisively in favour of the employer, to whom the employees, as his ‘retinue’, now owed a duty of loyalty. The results of the elections to the ‘Councils of Trust’ in spring 1934 were so poor that the regime did not publish them. In addition to the economic problems, there was the continuing conflict within the Protestant Church, which also involved Hitler’s prestige, as he had strongly supported the ‘unification project’. But, above all, people were alienated by the loutishness of the SA and the high-handed behaviour of the local Party bigwigs. There was little left of the euphoria inspired by a new beginning that the regime had had some success in creating during the previous year.62

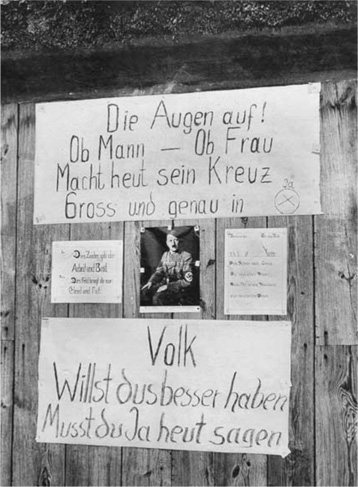

Typically, the regime responded not by addressing the causes of the crisis but by using every means possible to silence opponents and those allegedly responsible for encouraging ‘negativity’. After Hitler had used his speech on 1 May for a renewed attack on ‘critics’ in general, on 3 May the Nazi Party’s Reich propaganda headquarters launched a ‘comprehensive propaganda campaign involving meetings’, ‘which will focus, in particular, on whingers and critics, rumour-mongers and losers, saboteurs and agitators, who still think they can damage National Socialism’s constructive work’. The campaign was intended through ‘a barrage of meetings, demonstrations, and events to mobilize the people against this plague’. Deploying the ‘old methods of the time of struggle, the meetings [must] mobilize everybody right down to the last village, up the tempo every week, make ever tougher demands on people, putting in the shade all previous campaigns through their impact and success’. The date fixed for the conclusion of the campaign appears, in view of later events, remarkable: 30 June 1934. However, the campaign was not directed, or at least not in the first instance, against the SA, but above all against criticism from ‘reactionary’ and Church circles, in other words, opponents who were suspected of using the obvious tensions between the regime and the SA for their own purposes.63

However, the population was becoming tired of campaigns. They did not want to be mobilized yet again, and took the ‘whinger campaign’ for what in effect it was, namely a ban on all criticism. The response was indifference, apathy, and a further loss of trust.64 At the same time the economic situation deteriorated still further. The foreign exchange crisis reached its climax in mid-June 1934 when Schacht announced the suspension of interest payments on all Reich bonds from 1 July,65 and, a few days later, the Reichsbank abolished its monthly foreign exchange control system, in future allocating foreign exchange on an ad hoc basis. German foreign trade was in danger of collapsing; there was the threat of a trade war between Britain and the Reich.66

It was now obvious what was indeed about to happen. As a result of a shortage of raw materials there were interruptions in production, in fact even temporary shutdowns, and bottlenecks in deliveries.67 The Reichswehr leadership responded to this situation by bitterly attacking the Reich Economics Minister, Kurt Schmitt.68 The collapse of his health at the end of June after only a year in office proved quite convenient, paving the way for Hjalmar Schacht, who was to pursue a new course in order to protect the rearmament programme. However, before Schacht took up his appointment, on 30 June, Hitler was to solve the most serious crisis his regime had hitherto faced in his own very particular way.

The crisis comes to a head

On 13 July, Hitler told the Reichstag that, at the beginning of June, he had had a five-hour conversation with Röhm, during which he had reassured him that all rumours to the effect that he was planning to dissolve the SA were despicable lies. We do not know what was actually said during this conversation, but Hitler’s comment suggests that it involved nothing less than the very existence of the SA. Moreover, Hitler added that he had complained to Röhm ‘about the increasing number of cases of unacceptable behaviour’, demanding that they should be ‘stopped at once’.69 After the meeting with Hitler, Röhm published a statement that he was ‘going on leave for several weeks on the grounds of ill health’, in order to take a cure, while during July the whole of the SA would go on leave. Röhm felt it necessary to add that after this break he ‘would carry on his duties to the full’ and that, ‘after its well-earned holiday, the SA [would], unchanged and with renewed energy, continue to perform its great tasks in the service of the Führer and the movement’.70

In the meantime, however, Hitler’s conservative coalition partners, who had been losing ground since spring 1933, saw in the conflict a chance to regain the initiative. The deteriorating economic situation, the general discontent, and the regime’s insecurity, as demonstrated by the whingers campaign, encouraged this group to go on the offensive. Their hopes rested on the aged Hindenburg making a last stand. They assumed that if, with the aid of the President, they could get the Reichswehr to curb the SA, then this must have an effect on the balance of power within the government.71 Moreover, the idea of possibly restoring the monarchy as a stabilizing factor was prevalent in these circles. In the middle of May, Papen informed Hitler that, at his suggestion, Hindenburg had prepared a will. Unaware of its contents, Hitler’s entourage suspected that it might contain a recommendation to restore the monarchy. Hitler, therefore, prepared to prevent its publication after Hindenburg’s death.72 (It turned out that their fears were groundless, as Hindenburg had not followed Papen’s advice.)73 Meanwhile, during May, Goebbels had learnt from Blomberg that Papen was proposing to succeed Hindenburg himself.74 However, the previous summer, Hitler had already decided that he would take over the Reich Presidency on Hindenburg’s death.75

During the second half of July, the crisis intensified. On 17 June, Papen gave a speech at the University of Marburg, bluntly criticizing the Nazis’ totalitarian ambitions and rule of terror.76 Hitler (and not Goebbels, as Hitler told Papen) banned the press from publishing the Vice-Chancellor’s speech.77 Papen did not resign, pacified by Hitler’s explanations of what had happened, and also because Hindenburg failed to support him, indeed disapproved of his action as a breach of cabinet discipline. When Hitler visited Hindenburg at Neudeck on 21 June, the Reich Chancellor and the Reich President were in full agreement.78

On 23 June, Hitler went down to the Obersalzberg and, during the following days, decided to combine the neutralization of Röhm, which he considered unavoidable, with a crackdown on ‘reactionaries’, who were becoming increasingly self-confident. In short, he determined to liquidate a number of second-rank people in the conservative camp in order to crush this emerging centre of opposition. This blow against the conservative opposition would take place in the shadow of the crushing of an alleged ‘Röhm putsch’. By transforming his conflict with the SA leadership into an attempted putsch by the SA leader, he could justify his brutal settling of accounts with his opponents within the Nazi movement as ‘an affair of state’. He claimed to be dealing with a ‘national state of emergency’, and he included the planned murder of members of the conservative camp under this heading. He could be certain that the majority of the population, and particularly the bourgeoisie, would welcome with relief the removal of the problems caused by the SA; indeed, that it would gain him respect. He reckoned that this support for the neutralization of the SA would lead the conservative elements in society to overlook the murder of a few of their number. He did not leave the sorting out of the SA to their major rivals, the Reichswehr, instead transferring it to the political police and the SS. In doing so, he was fulfilling the promise that he had made to the Reichswehr leadership at the start of his regime: in future, the Army would be kept out of domestic conflicts. At the same time, the neutralization of the SA would strengthen his alliance with the Reichswehr as the ‘nation’s sole bearer of arms’ – the promise Hitler had made to it on 28 February 1933.

During the final days before the crackdown, there were plenty of warnings from the Party leadership. During the annual Gau Rally in Gera on 18 June, for example, Goebbels attacked ‘saboteurs, grumblers, and malcontents’ (while Hitler devoted his speech to foreign policy issues); and three days later, at Gau Berlin’s solstice celebration, Goebbels announced that there would be a ‘tough settling of accounts’ with the ‘posh gentlemen’ and the ‘whingeing pub strategists’.79 On 25 June, Rudolf Hess warned the SA, in a speech broadcast via the Cologne radio station: ‘Woe to him who breaks faith in the belief that he can serve the revolution by starting a revolt! Those people who believe that they have been chosen to help the Führer through revolutionary agitation from below are pathetic. . . . Nobody is more concerned about his [sic] revolution than the Führer.’80 The following day, at a Party event in Hamburg, Göring railed against reactionary ‘self-interested cliques’ and ‘barren critics’, declaring that anyone who attempted to undermine people’s trust in the regime, will have ‘forfeited his head’.81

At this point, during the final phase of the crisis, the Reichswehr too got ready for action. From 28 June, the Army made preparations for an imminent violent struggle with the SA; on 29 June, Defence Minister Blomberg announced in the Völkischer Beobachter: ‘the Wehrmacht and the state are of one mind’. In the same edition a speech of Göring’s in Cologne was reported, in which he railed against ‘people who are stuck in the past and who sow divisions’, while in Kiel Goebbels attacked ‘whingers and critics’.82 Finally, on 30 June, Infantry Regiment 19 was prepared, if necessary, to restore law and order in the Tegernsee district; later on in the day, it was to take over securing the Brown House in Munich.83

A bloody showdown

On 28 June, Hitler attended the wedding of the Essen Gauleiter, Josef Terboven, and subsequently visited the Krupp steel plant. The previous day, he had told Rosenberg that he did not intend to move against so-called ‘reactionaries’ until after Hindenburg had died.84 During his trip to Essen, however, he received news of some kind from Berlin that prompted him to consult with, among others, Göring and SA Obergruppenführer Viktor Lutze, who were accompanying him. Following these consultations, Göring flew back to Berlin, and Hitler ordered Röhm to convene a meeting of all the senior SA leaders in Bad Wiessee on the Tegernsee, where the latter was spending his holiday.85 The following day, Hitler continued his tour of Westphalia and then travelled to Bad Godesberg, where he ordered Goebbels to fly in to see him from Berlin. During the previous days, Goebbels had been convinced that Hitler was preparing a blow against ‘reactionaries’, and so was very surprised to learn that he was planning to move against ‘Röhm and his rebels’ and was going to ‘spill blood’. ‘During the evening’ according to Goebbels, they received more news from Berlin (‘the rebels are arming’), prompting Hitler to fly to Munich that night.86

In his speech to the Reichstag on 13 July 1934, in which he gave a detailed account of the ‘Röhm putsch’, Hitler was to claim that he had originally intended to dismiss Röhm at the meeting in Bad Wiessee and to have the ‘SA leaders who were most guilty arrested’. However, during 29 June, he had received ‘such alarming news about final preparations for a coup’ that he had decided to bring forward his flight to Munich, so that he could act ‘swiftly’, ‘taking ruthless and bloody measures’ to prevent the alleged coup. Göring had ‘already received instructions from me that in the event of [sic!] the purge occurring, he should take equivalent measures in Berlin and Prussia’.87 Hitler’s comments, and the entry in Goebbels’s diary concerning Hitler’s surprising change of plan, suggest that Hitler did indeed decide to get rid of the SA leadership on 28 June, and, on 29 June, made the final decision on the extent, the precise targets, and the murderous nature of the ‘purge’. The ‘alarming news’, of which Hitler spoke and which Goebbels summarized with the words the ‘rebels are arming’, presumably referred to the latest Gestapo information about the circle around Papen’s colleague Edgar Julius Jung, who had been arrested on 25 June.88 It suggested that this group was attempting to make a final approach to Hindenburg,89 and Hitler was determined to preempt this at all costs through his double blow against the conservatives and the SA leadership. However, from 29 June onwards, he was no longer simply concerned with winning a domestic political power struggle; he was now determined to annihilate his opponents physically and create an atmosphere of terror and fear, which would in future prevent any opposition from forming at all.

However, to begin with Hitler carried out the Bad Godesberg programme that had been organized for him as planned.90 Late in the evening of 29 June, he had two companies of SS sent to Upper Bavaria on the overnight train. During the night, he flew from Hangelar airport near Bonn to Munich, accompanied by his adjutants, Brückner, Schaub, and Schreck, his press chief, Otto Dietrich, and Goebbels. Once there, he learnt that, during the night, the members of an SA Standarte, around 3,000 men, had been put on the alert, some of whom had marched rowdily through Munich. It seemed there was a possibility that preparations for the planned measures had leaked out or had been intentionally leaked. Hitler, therefore, now decided to further accelerate the measures. He drove to the Interior Ministry, ordering SA leaders August Schneidhuber and Wilhelm Schmid to meet him there, and then personally tore off their insignia.91

Hitler’s decision to liberate the regime from a serious crisis through a double blow against the SA leadership and the circle round Papen had been maturing over a period of weeks. However, events now culminated in a dramatic confrontation and the more the situation escalated the more furiously angry he became. However, his behaviour was not simply a clever tactic to provide himself with a justification for his actions. For, given his anger, a cool calculated decision to have a number of old comrades murdered could have appeared to be a crackdown arising out of the situation. It is also explicable in terms of particular personal characteristics that determined how he saw the situation. If this is the case, then the question as to whether Hitler really believed the SA intended to carry out a putsch is of secondary importance. He saw any putative attempt by the conservatives to approach Hindenburg as a threat to his power, which, together with the growing SA problem, could lead to a serious political crisis. This growing threat to his position and prestige – for him an intolerable thought – was already itself the feared ‘putsch’, the threatened coup d’état. His response to this threat, as he saw it, was to unleash a tidal wave of violence.

In this mood he did not wait for SS reinforcements to arrive in Munich from Berlin and Dachau. Instead, he drove to Bad Wiessee, accompanied by Goebbels and a small group of SS and criminal police, where he found the SA leaders still in bed. Hitler insisted on carrying out the arrests himself.92 Afterwards, he returned to Munich, on the way stopping cars bringing the remaining SA leaders to Wiessee and arresting some individuals.

On 8 July, Rudolf Hess provided an account of what happened in the Brown House during the next few hours in a speech at a Gau Party Rally in Königsberg that was broadcast on the radio. To begin with, Hitler spoke to the political leaders and SA leaders who were present, after which he withdrew to his study to pass ‘the first sentences’.93 He then dictated various instructions and statements concerning the ‘change of leadership’ at the top of the SA. These included the announcement of Röhm’s dismissal and the appointment of Lutze as his successor, as well as a ‘statement from the NSDAP’s press office’, which provided an initial summary of the events and an explanation of the measures that had been taken.

According to the statement, the SA had been increasingly developing into a centre of opposition, and Röhm had not only failed to prevent this, but had actually encouraged it, with his ‘well-known unfortunate inclinations’ playing an important part. Röhm had also, along with Schleicher, conspired with a ‘foreign power’ (France). This was another accusation for which no proof was produced.94 Hitler had then made up his mind to ‘go to Wiessee in person, together with a small escort’, ‘in order to nip in the bud any attempt at resistance’. There they had witnessed ‘such morally regrettable scenes’ that, following Hitler’s orders, they had acted immediately, ‘ruthlessly rooting out this plague sore’. Moreover, he had ordered Göring ‘to carry out a similar action in Berlin and, in particular, to eliminate the reactionary allies of this political conspiracy’. Around midday, Hitler had addressed senior SA leaders, on the one hand emphasizing ‘his unshakeable solidarity with the SA’, but, at the same time, announcing his ‘determination, from now onwards, pitilessly to exterminate and destroy disobedient types lacking discipline, as well as all anti-social and pathological elements’.95

The next press statement, which went out on 30 June, was a so-called eye-witness report, in which Hitler’s personal intervention against the ‘conspiracy’ was praised as a truly heroic deed, while the ‘disgusting scenes taking place when Heines and his comrades were arrested’ were left to the readers’ imagination. Edmund Heines, the SA leader in Silesia, was one of the SA leaders whose homosexuality was relatively well known.96

Also on 30 June Hitler issued an ‘order of the day’ to the new SA chief of staff, Lutze, containing a catalogue of twelve demands to the SA. Among other things, Hitler demanded ‘blind obedience and absolute discipline’, exemplary ‘behaviour’ and ‘decorum’. SA leaders should in future set ‘an example in their simplicity and not in their extravagance’; there should be no more ‘banquets’ and ‘gourmandizing’; ‘expensive limousines and cabriolets’ should no longer be used as official cars. The SA must become a ‘clean-living and upright institution’ to which mothers can entrust their sons without any reservations’; the SA must in future deal ruthlessly with ‘offences under §175’.* When it came to promotions the old SA members should be considered before the ‘clever late-comers of 1933’. In addition, he demanded ‘obedience’, ‘loyalty’, and ‘comradeship’.97

These statements referred to treason and mutiny, to a conspiracy by the SA leadership and ‘reactionary forces’. Yet these initial announcements did not state that Germany had been facing the immediate threat of a putsch that had been in preparation for a long time, as Hitler was later to claim. Instead, the main justification for the crackdown was disgust at the alleged moral depravity of the SA leadership.

Around five o’clock in the afternoon, Hitler summoned Sepp Dietrich, the commander of his personal bodyguard, the SS Leibstandarte, ordering him to go to Stadelheim prison with his unit and shoot six SA leaders whose names were marked with a cross on a list. Dietrich carried out the order. The victims were Obergruppenführer August Schneidhuber (Munich) and Edmund Heines (Breslau), the Gruppenführer Wilhelm Schmid (Munich), Hans Hayn (Dresden) and Hans-Peter von Heydebreck (Stettin), and Röhm’s adjutant, Standartenführer Count Hans Erwin Spreti. The shooting of these people was also announced by the NSDAP press office.98

Around eight o’clock in the evening, Hitler flew from Munich to Berlin. Göring was waiting for him at the airport and, according to Goebbels, who was still accompanying him, reported that everything in Berlin had ‘gone according to plan’. Indeed, in the meantime, the Gestapo had carried out a series of murders involving a number of prominent individuals: General von Schleicher, who had been shot at home together with his wife (which Goebbels referred to as a ‘mistake’) and his closest colleague, Major-General Ferdinand von Bredow; in addition, Papen’s colleague, Herbert von Bose, Erich Klausener, who had been dismissed as head of the police department in the Prussian Interior Ministry in February 1933, and was also the head of the Berlin diocesan section of the Catholic lay organization, Catholic Action, and Edgar Jung, who was already under arrest. The following day, Göring reported to Hitler on how the executions were proceeding. Goebbels noted in his diary: ‘Göring reports: executions almost completed. Some still necessary. That’s difficult, but essential. Ernst, Strasser, Sander, Detten †.’ Goebbels was referring to the Berlin SA Gruppenführer, Karl Ernst and his chief of staff, Wilhelm Sander, to Hitler’s long-time colleague and Party opponent, Gregor Strasser, and to the head of the SA’s political office, Georg von Detten, who lived in Berlin. Goebbels, who spent the whole afternoon with Hitler, noted: ‘the death sentences are taken very seriously. All in all about 60.’99 It is clear from Goebbels’s diary that Hitler remained in close contact with Göring from the time of his arrival in Berlin on the evening of 30 June, and determined himself the later murders that took place, just as it was he who had personally ordered the execution of the six SA leaders in Munich.

After the initial executions in Stadelheim, the murders continued in Munich. They involved, in the first place, Röhm’s entourage: the chief of his staff guard, two adjutants, two chauffeurs, the manager of his favourite pub, and his old friend, Martin Schätzel.100 Secondly, Hitler focused on getting rid of a number of people who had crossed his path in earlier times and antagonized him. We can be certain that they were among the ‘death sentences’ Goebbels definitely attributed to Hitler. Among them were Otto Ballerstedt, the former chairman of the long-forgotten Peasant League. In September 1921 (!) Hitler had used violence to break up one of his meetings and been sent to prison for three months. He had had to spend four weeks inside, a humiliation which he hated mentioning. Hitler naturally blamed Ballerstedt for his punishment and from then onwards kept claiming that this marginal figure was a very dangerous opponent.101 Gustav von Kahr was murdered. He was the man whom Hitler had wanted to force to join his putsch on 8 November 1923, but who after a few hours had managed to escape and then played a significant role in the collapse of the whole enterprise. For Hitler, Kahr, who had long since withdrawn from politics, was, more than ten years later, still the ‘traitor’ he blamed for his greatest humiliation.102 Fritz Gerlich, a politically engaged Catholic, was also murdered. In his journal, Der Gerade Weg, he had mounted a campaign against Nazism, including bitter personal attacks on Hitler. In June 1932, for example, he had subjected Hitler to an ‘examination’ on the basis of the various racial criteria put forward by the Nazis, and reached the conclusion that, on the basis of his appearance and attitudes, Hitler should be classified as an ‘inferior’, ‘eastern-Mongolian’ type. Gerlich had already been placed in ‘protective custody’ in March 1933.103 Another case worth mentioning in this context is that of Bernhard Stempfle, a völkisch writer who, despite his ideological affinity to Nazism, during the 1920s developed a strong personal animosity towards Hitler. Shortly after its publication, he wrote a devastating review of Mein Kampf that appeared in the völkisch newspaper, the Miesbacher Anzeiger.104

The murders of Ballerstedt, Kahr, Gerlich, and Stempfle all followed the same pattern. To begin with, the victims were taken to Dachau concentration camp and then either killed there or nearby. The head of the Munich Student Welfare Service, Fritz Beck, was also murdered, possibly because he was assumed to have a close relationship with Röhm (in 1933 he had made the SA chief of staff honorary chairman of the organization).105 The music critic, Wilhelm Schmid, was the victim of mistaken identity. In addition, there were at least five more victims: a communist, a Social Democrat, two Jews, and the private secretary and girlfriend of the former editor of the Münchener Neueste Nachrichten, who had had a row with the Party.106 In Berlin the murder campaign involved not only those people already mentioned, but half a dozen colleagues of the local SA leader and Röhm’s press chief, Veit-Ulrich von Beulwitz, as well as three other people who were eliminated for various reasons that did not necessarily have anything to do with the ‘Röhm putsch’.107

Apart from Munich and Berlin, Silesia was a third centre where similar measures were taken on 30 June. A dozen SA leaders who were linked to the SA chief, Heines, were murdered on the orders of the responsible SS Oberabschnittsführer, Udo von Woyrsch. There were others who for some reason were targeted by the SS, including four Jewish citizens of Hirschberg.108 A fourth focus for the murder campaign was Dresden, where three SA members were killed.109

Elsewhere, other people fell victim to the purge for various reasons. In some cases, it appears that ‘old scores were being settled’ by individuals acting on their own initiative. Among these were, for example, Freiherr Anton von Hohberg und Buchwald, who had been dismissed from the SS as a result of a row with the East Prussian SS leader, Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski, who had him murdered, and Hermann Mattheiss, who had been dismissed as head of the Württemberg political police in May 1934 because he refused to submit to the new head of the political police in Württemberg, Heinrich Himmler; instead, he wanted to continue to rely on SA support for the police. Mattheiss was shot in the SS barracks in Ellwangen.110

Adalbert Probst, Reich leader of the Deutsche Jugendkraft, the umbrella organization of the Catholic gymnastic and sports associations and one of the most prominent representatives of those Catholic associations that were in conflict with the state, was arrested in Braunlage in the Harz and murdered at an unknown location. Probst had made a name for himself as an advocate and organizer of paramilitary sport within the Catholic associations, and so was considered a representative of a truly ‘militant’ Catholicism. At the end of June, he had taken part in the Concordat negotiations in Berlin, which were dealing, among other things, with the future of the Catholic associations.111 Kurt Mosert, the leader of SA Standarte Torgau, was taken to Lichtenberg concentration camp and murdered because of personal quarrels with SS guards in the camp,112 as were three members of the SS who had been imprisoned for ill-treating prisoners.113

On 1 July, Hitler arranged for Röhm to be given a pistol in his cell in Munich-Stadelheim. When he failed to use it, Hitler sent the commander of Dachau concentration camp, Theodor Eicke, and the commander of the Dachau guards, Michael Lippert, to Stadelheim to shoot him in his cell.114 The regime then put out a laconic press release: ‘The former chief of staff of the SA, Röhm, was given the opportunity of facing up to his treason. He failed to do so and consequently has been shot.’115

On the evening of 1 July, Goebbels described the recent events in a broadcast, adopting the tone of moral indignation that had been prominent in the official statements of the previous day. He accused those who had been murdered and their associates of ‘leading a dissolute life’, of ‘ostentation’ and ‘gourmandizing’; they had been liable to place the whole of the Nazi leadership under suspicion of being associated with ‘disgraceful and disgusting sexual abnormality’. All their doings and actions had been dictated purely by ‘personal lust for power’.116

On 2 July, Hindenburg sent telegrams to Hitler and Göring expressing his ‘warm appreciation’ that ‘through your resolute intervention and courageous personal engagement you have managed to nip these treasonous machinations in the bud’. On the same day, Hitler issued a press statement announcing the conclusion of the ‘purge’.117

When considering the events of 30 June, it is often overlooked that the murderous campaign was not only directed against the SA leadership and the conservatives (as well as a number of ‘old’ enemies), it was also intended as a warning to ‘political Catholicism’. Moreover, this was at a time when a political compromise between the Nazi system and the Catholic Church was actually emerging. This aspect throws further important light on Hitler’s decision to neutralize various opposition forces through a brutal and sweeping blow.

In October 1933, negotiations had already begun between the Reich and the Vatican concerning the implementation of various points in the Concordat of July 1933. They concerned, in particular, the future of those Catholic associations whose activities were not purely religious in nature; the issue was basically whether the Catholic youth organizations should retain a degree of autonomy, for example through being integrated into a state youth organization, or whether, as the Party wished, they should be absorbed into the Hitler Youth.

The final round of these negotiations was scheduled for the end of June in Berlin after the Vatican had instructed the German episcopacy to engage in direct talks with the regime.118 On 27 June, Hitler, accompanied by Frick and Buttmann, received the delegation of the German bishops and he appears to have impressed his visitors with his sympathetic and responsible manner and his rejection of another ‘cultural struggle’.† Indeed, he even stated that he was prepared to ban the advocacy of a ‘Germanic religion’ and ‘neo-heathen propaganda’119 (a promise, which, significantly, he immediately withdrew when he met Rosenberg, the main exponent of this doctrine).120 Evidently, Hitler felt the general political situation obliged him to go to some lengths to conciliate the Catholic Church.

Two days later, they made an agreement, determining that the associations that served purely religious, cultural, or charitable purposes should be subordinated to the Catholic lay organization, Catholic Action, and so be integrated into the Catholic Church’s hierarchy.121 On 24 June, when the Berlin diocese celebrated Catholic Day, Erich Klausener, the head of Catholic Action in Berlin, urged his enthusiastic audience of 60,000 Catholics proudly to stand up for their Catholic faith in their daily lives. This rally must have been viewed by the regime as a demonstration of Catholic opposition; it looked as though, in addition to the SA and the conservative opposition, another domestic threat was now emerging on the horizon.122 As a result of the impending implementation of the Concordat, Klausener’s organization was now going to be strengthened and receive state recognition. Six days later, Klausener was murdered, as was the well-known Catholic journalist, Fritz Gerlich, and the head of the Deutsche Jugendkraft, Adalbert Probst, like Klausener both representatives of a self-confident and militant Catholicism; Probst had also taken part in the Concordat negotiations at the end of June.

Seen in context, these three murders were a targeted blow against the emergence of a political opposition movement. There is a suspicion – it cannot be proved because of a lack of documentation – that these murders were intended at the last minute to block the compromise on the implementation of the Concordat worked out by the Interior Ministry because the Party disapproved of it. This was facilitated by the fall from power of Vice-Chancellor, Papen, the government minister who was most supportive of a modus vivendi between Catholicism and the regime. The compromise solution, which had appeared to the regime unavoidable on 29 June, could be revised on 30 June because of a completely changed political situation.

Bearing in mind how directly involved Hitler was in the issuing of the ‘death sentences’ on 30 June and 1 July, it appears improbable that the arrest and murder of these three prominent Catholics in different locations was the result of unauthorized actions by subordinate agencies. It is much more likely that they too were victims of Hitler’s ‘death sentences’.

The Catholic Church was horrified by the murder of the three Catholics, but it did not use the murders as an excuse for breaking off negotiations with the Reich government. This is probably one reason why the link between the Concordat negotiations and the murder of prominent Catholics has hitherto been neglected in historical accounts of the events of 30 June. In a letter to Cardinal Bertram, Eugenio Pacelli described the agreement reached on 29 June as unacceptable and referred, in an oblique way typical of representatives of the Vatican, to the events of 30 June. This ‘writing on the wall’ would hopefully ‘convince the holders of ultimate power in Germany . . . that external force without the corrective and the blessing of a God-directed conscience will not prosper but bring disaster to the state and the people’.123

It was only several days after 30 June 1934, and then remarkably hesitantly, that Hitler’s regime went beyond the confused statements that had been made in the immediate aftermath of the events and provided a properly thought-through justification for the murders.

To begin with, on 3 July, Hitler gave a detailed explanation of the action against Röhm at a cabinet meeting, taking ‘full responsibility for the shooting of 43 traitors’ (even if ‘not every on-the-spot execution had been ordered by him personally’).124 The Reich cabinet then approved a Law concerning Emergency Measures, whose single clause read: ‘The measures taken on 30 June and 1 July 1934 to suppress high treason and treasonable actions are, as emergency measures to defend the state, legal.’125 According to Goebbels, Papen suddenly appeared at the meeting, looking ‘quite broken’.126 Although his colleagues, Edgar Julius Jung, who had written the Marburg speech, and Herbert von Bose had been among the victims, by appearing at the meeting Papen was indicating that he intended to continue with his official duties. The cabinet was particularly busy that day, issuing a total of thirty-two laws.127

On 3 July, Hitler visited Hindenburg at his Neudeck estate. On the following day, he returned to Berlin, but then did not appear in public for over a week.128 He also did not take part in the meeting of Gauleiters on 4 and 5 July 1934 in Flensburg, where, according to the Völkischer Beobachter, Hess only briefly referred to recent events; apart from that, the Gauleiters discussed organizational and economic issues.129 On 11 July, the Deutsches Nachrichtenbüro, the official German news agency, issued the text of an interview Hitler had given to Professor Pearson, a former US diplomat, which had appeared in the New York Times. Here, he had defended his measures on the grounds that he had acted to prevent a civil war.130

Hitler did not appear in public again until 13 July. In the meantime, he had decided to justify his actions on 30 June as emergency measures, required to counter an elaborate conspiracy, and now appeared before the Reichstag with this imaginatively concocted story. He began his speech by listing the opposition groups in the Reich: first, the communists; secondly, political leaders who could not come to terms with their defeat on 30 January 1933; thirdly, he dealt with those ‘revolutionary types, whose earlier relationship to the state had become disrupted in 1918, who had become rootless and, as a result, had lost any connection with a regulated social order’; the fourth group he described as ‘those people, who belong to a relatively small social group who, without anything else to do, while away their time in chatting about anything liable to bring variety into their otherwise completely trivial lives’.

Hitler then outlined a scenario in which a conspiracy was thwarted at the very last minute. He did this by ingeniously combining a number of issues that had been causing controversy during recent months and assigning key roles in them to particular individuals who had been murdered. The rumour of an impending dissolution of the SA had been used, he claimed, as an excuse for a ‘second revolution’, during which, among other things, Papen was to be killed; Röhm was planning to subordinate the Wehrmacht to the SA and to make Schleicher Vice-Chancellor; von Bredow had established contacts with foreign countries and Gregor Strasser had been ‘brought into’ the conspiracy. If anyone ‘reproached him for not using the law courts to try’ the conspirators, his answer was: ‘In this hour I was responsible for the fate of the German nation and so I was the German people’s supreme judge!’ He gave the number of people who had been executed as seventy-seven.131 The actual number of those murdered was higher. Up to the present, a total of ninety-one people have been proved to have died; it is possible that there were further victims.132

Hitler gave a very different justification for the measures taken on 30 June 1934, one much closer to the truth, in a secret speech to the Party’s district leaders at the Ordensburg Vogelsang on 29 April 1937. He stated: ‘. . . to my great sadness I had to break that man and I destroyed him and his followers’ and gave as his justification: ‘the need to show the most brutal loyalty’ to the army, whereas the SA’s idea of a militia would have resulted in a ‘militarily completely useless bunch of people’.133

On 20 July, Hitler ordered that, ‘in view of its great services, particularly in connection with the events of 30 June 1934’, the SS was to be promoted to be an ‘autonomous organization within the NSDAP’. The leader of the SS, who previously had been subordinate to the chief of staff of the SA, would in future be directly subordinate to him in his capacity as ‘Supreme SA leader’134. In this way Hitler prepared the path for SS chief, Heinrich Himmler, one of his most important allies during the 30 June action, to build up his ‘Black Order’ to become one of the main centres of power in the Third Reich.

The crisis of spring and early summer 1934 had resulted from a whole number of factors, as we have seen: against the background of the Reichswehr’s rapid rearmament, the SA had been quickly forced out of its military role and was searching aggressively but unsuccessfully for new tasks. This was a process that was bound to lead to numerous conflicts and, above all, raised the question of the goals of the ‘National Socialist revolution’, one which could never be decisively answered. In addition, there were supply problems as well as a shortage of foreign exchange; the unresolved conflict within the Protestant Church and the equally unresolved issue of the Catholic associations; the discontent with the high-handed behaviour of the local Party bosses; and, finally, the growing self-confidence of the conservatives around Vice-Chancellor von Papen, who wanted to take advantage of the confused situation while Reich President von Hindenburg was still alive. Basically, a power struggle was developing between the regime, the Reichswehr, and the SS/political police on the one hand and the two very different centres of opposition around the SA and Papen’s circle on the other.

Hitler’s response to this complex pattern of conflicts was typical of him: radical, almost hysterical, driven by his wish to avoid the threat of a loss of face. The orgy of violence, including the settling of old personal scores, went beyond the need to deal with the actual political conflicts that existed. Hitler wanted to make it clear once and for all how he proposed to deal with opponents of any kind and to take revenge for past humiliations. Consequently, he subsequently took responsibility for the murders, under the cover of an incredible tissue of lies.

By removing his opponents in the SA leadership and the Papen circle, and simultaneously intimidating the Catholic Church, he had gained considerable room for manoeuvre; he had succeeded in shifting the political balance of forces in his favour. Yet most of the causes of the crisis remained and would, as a result, re-emerge in another temporal context and in a different constellation. This is confirmed by the official regime reports on the mood of the population and by the observations of the Social Democratic underground movement. Apart from the shock and horror the events had produced, the reports initially reflected the ‘positive’ interpretation put out by the regime’s propaganda. For large sections of the population Hitler once more appeared as the decisive political leader, who in his ‘resort to drastic measures’ had the ‘welfare of the state’ at heart. However, ‘relief’ at being liberated from the irksome and loutish behaviour of the SA lasted only a short time; for it soon became clear that 30 June was not, as many hoped, the start of a general purge of the Party of all the ‘bigwigs’, the beginning of an energetic drive against the misuse of power and corruption. It was not long before there was a general revival of ‘whingeing’ and grumbling’.135

The Austrian putsch

A few weeks after his victory over his domestic political opponents, Hitler thought he could solve another major problem facing the young Third Reich: the so-called Austrian question. He was convinced that he had secured the most important precondition for the solution of this problem: Mussolini’s agreement to an Anschluss.

On 14 June, Hitler had carried out his first state visit to Italy. He and his Foreign Minister Neurath had met the ‘Duce’ and the most important Italian politicians in Venice.136 Austria had been at the top of the agenda during the two detailed discussions Hitler had with Mussolini in Venice. The ‘Führer’ had made it clear: ‘the question of the Anschluss was not a matter of interest since it was not pressing and, as he well knew, could not be carried out in the present international situation’. However, he demanded an end to the Dollfuss regime: ‘the Austrian government [must] be headed by a neutral personality, i.e one not bound by party ties’, elections must be held, and then Nazis must be included in the government. All matters affecting Austria must be decided by the Italian and German governments. While the Italians agreed these points, Mussolini responded to Hitler’s insistence that Italy should ‘withdraw its protective hand from Austria’ by merely ‘taking note’ of it. It is incomprehensible how Hitler could have gained the impression from these conversations that Mussolini would not respond to an attempted coup by the Austrian Nazis, authorized by Hitler a few weeks later. For Mussolini, under pressure from the Reich, had let it be known that he would at best tolerate the Austrian Nazis, forcing new elections to be held and a reconstruction of the government. However, he was by no means prepared to accept a bloody coup d’état; indeed, in view of Hitler’s explicit renunciation of an Anschluss, he was bound to consider it a breach of faith. This fateful mistake, a complete misunderstanding of his ‘friend’, delayed for years both the alliance with Italy, to which he had aspired since the 1920s, and his Austrian plans. It can only be explained in the light of the euphoria and wishful thinking gripping Hitler during the domestic political crisis of early summer 1934. Thus, he believed that two basic aims of his foreign policy were about to be realized: the alliance with Italy and the ‘coordination’ of Austria, goals that he had had to play down the previous year. Yet neither Hitler’s wishes nor his ideas reflected reality.

The meeting in Venice was the starting point for the Austrian Nazis’ preparations for a putsch. They were organized by Theodor Habicht, the ‘Landesinspekteur’ for the Austrian NSDAP, appointed by Hitler, and by the leader of the Austrian SA, Hermann Reschny, who, after the ban on the Austrian NSDAP, had established an ‘Austrian Legion’ in the Munich area, composed of SA members who had fled Austria. The third figure in the conspiracy was the former SA chief, Pfeffer. He was now a member of the NSDAP’s liaison staff in Berlin and, apart from his role as Hitler’s representative for Church questions, was now given the task of solving the Austrian question by force. In the historical literature there has been much speculation that the affair was basically triggered by competition between Habicht and Reschny.137 According to these historians, cooperation between the SA and SS had been so damaged by the events of 30 June that Reschny, an SA leader, had not properly supported the actual putsch force, an SS unit. Hitler had remained largely passive and had simply ‘let things drift’, as Kurt Bauer put it a few years ago in a substantial work on the July putsch.138 This perspective reflects the ‘functionalist’ interpretation of a dictator, who, as a result of his wait-and-see style of leadership, encouraged his subordinates, who were trying to ‘work towards him’ and at the same time competing with each other, to make great efforts to do what they perceived as his bidding. This, in turn, allegedly led to a radicalization of the decision-making process. In this model Hitler appears, above all, as one factor among many others within the system’s own dynamic; it is the system that acts and not the dictator.

However, this version can be refuted with the aid of Goebbels’s diary for the summer of 1934, which was published in 2006. For it is clear from Goebbels’s diary that, on 22 July, accompanied by Goebbels, Hitler received in Bayreuth, first, Major-General Walter von Reichenau, Chief of the General Staff in the Defence Ministry, and then the three organizers of the putsch: Habicht, Rechny, and Pfeffer.139 Concerning the content of these negotiations, Goebbels noted: ‘Austrian question. Will it succeed? I’m very sceptical.’140 Goebbels’s scepticism was to prove justified. On 25 July, members of an Austrian SS Standarte carried out the putsch that Hitler had ordered. They occupied the Austrian broadcasting station and the Federal Chancellor’s office, seriously injuring Chancellor Dollfuss and letting him bleed to death in his office. However, on the same day, the putsch was crushed in Vienna by troops loyal to the government,141 and, during the following days, the uprising, which had spread quite widely, was completely suppressed.142 The Goebbels diaries show in detail that, while in Bayreuth, Hitler was carefully and anxiously following developments in Austria.143

On 26 July, Habicht and Pfeffer appeared in Bayreuth to give their report. Habicht was forced to resign and, a few days later, the Austrian NSDAP headquarters was dissolved. Mussolini’s immediate support for the Austrian government was decisive for the failure of the putsch.144 Hitler was extremely disappointed; he could not bring himself to admit that he had completely misunderstood Mussolini in Venice.145 On 26 July, in order to cover up the involvement of German agencies, Hitler issued a statement that ‘no German agency had anything to do with these events’. The fact that the putsch had been supported by reports from the Munich radio station was a mistake for which Habicht was held responsible.146 Hitler also decided to appoint Papen, who had lost his post as Vice-Chancellor, as the new ambassador in Vienna. His close connections with the Catholic Church were intended to help restore the damaged relationship with Austria.147

The death of Hindenburg

The signing of Papen’s accreditation document as special ambassador on 31 July was the last official act Reich President von Hindenburg was capable of carrying out. For having withdrawn to his Neudeck estate at the beginning of June on grounds of ill health, at the end of July his condition worsened.148 Hindenburg’s imminent death gave Hitler the opportunity decisively to expand his power. As is clear from Goebbels’s diary, he had already discussed the steps to be taken with senior cabinet members and the Reichswehr leadership. They involved the Reichswehr and the cabinet ‘declaring Hitler to be Hindenburg’s successor immediately after [Hindenburg’s] demise. Then the Führer will appeal to the people’.149 On 1 August, Hitler flew to East Prussia, where he saw Hindenburg, still alive but barely responsive.150 Back in Berlin, on the evening of 1 August, Hitler told the cabinet that, within 24 hours, Hindenburg would be dead. At that point it was decided – not as originally envisaged immediately after the President’s death – to issue a law stating that on Hindenburg’s death his office would be combined with that of the Reich Chancellor, and so the presidential powers would transfer to the ‘Führer and Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler’. This totally contradicted the Enabling Law of 24 March 1933, which expressly stated that the rights of the Reich President remained unaffected.151