27

After Munich

After Munich Hitler was determined to go ahead as soon as possible with the plan he had been nursing since May 1938 of destroying Czechoslovakia, a plan that, for the time being, had been thwarted by a combination of domestic and foreign opponents. To achieve this, from October onwards, he set about destabilizing Czechoslovakia through internal and external pressure, making the border established in Munich appear merely provisional. Above all, however, during the Munich conference he was already engaged in strengthening ties with Japan and Italy, in order to avoid the Reich being integrated into a European four-power bloc, into which he was being forced against his will, and to establish a rival bloc against the western powers. At the same time, he wanted to achieve a ‘general settlement’ with Poland in order to place the alliance with this important partner on a permanent basis. However, in order to achieve greater diplomatic freedom of action and to continue his power politics he had to accelerate rearmament, which he also set in motion during the Munich conference. Apart from that, he was determined to take radical steps to overcome the German population’s evident lack of enthusiasm for war, as spectacularly demonstrated in September, and to underline the Party’s leadership role through a reorientation of domestic politics.

At Munich the issue of the cession of Czechoslovak territories mainly populated by Poles and Hungarians to these two countries had been initially postponed for three months. Germany and Italy were going to guarantee the integrity of Czechoslovakia only after this matter had been settled; the two western powers had already done so. Hitler was determined at all costs to avoid Germany having to give such a guarantee, for his aim was instead to encourage the ongoing disintegration of Czechoslovakia. Thus, during the coming months, he pursued the policy of declaring that the question of the non-German minorities in Czechoslovakia had not yet been ‘finally’ settled, the internal situation in Czechoslovakia must return to normal and so on, and, therefore, that the guarantee could not yet be given.1 He also soon found supporters of his destabilizing policy within Czechoslovakia itself.

Hitler gave up his previous plan of handing Slovakia over to Hungary after an autonomous Slovakian government was established on 6 October under Jozef Tiso, which succeeded in securing recognition from the central government in Prague. The opportunity of acquiring the Slovakian prime minister as a loyal ally, by supporting him against Prague and Budapest, and then using him to further German expansionist policy, was too tempting. Moreover, in view of Hungary’s passive stance during the Munich crisis, Hitler saw no further need to support its territorial claims.2

Hitler acquired another totally dependent ally and a land bridge to Romania through the creation, a few days later, of an autonomous government in Carpatho-Ukraine, the easternmost part of Czechoslovakia. Here too he gave up, albeit only for a few months, his previous plan of giving this territory to Hungary in order to meet Poland’s and Hungary’s wish for a common frontier.3 A further motive for this temporary change of policy was probably the thought that Carpatho-Ukraine could become the centre of a Ukrainian nationalist movement and therefore offer the possibility – albeit at this stage very vague – of influencing the Ukrainian minority in eastern Poland and in the Soviet Ukraine. At any rate, from 10 October onwards, German radio stations began broadcasting programmes in Ukrainian and supporting the cause of Ukrainian independence.4

Negotiations between Czechoslovakia and Hungary about a new definition of the border had just been broken off when, on 14 October, Hitler received the new Czechoslovak foreign minister, František Chvalkovský, and the former Hungarian prime minister, Kálmán Darányi, whom Budapest had sent as an emissary, for separate talks in Munich. During these talks, Hitler pressed both states to reach a rapid agreement about the future border based on ethnic criteria. He was determined to avoid at all costs this question being settled at an international conference, a second Munich, in other words once again having to submit to a process in which he would have to appear as an equal among equals.

Two weeks after Munich, Chvalkovský now hastened to inform Hitler of the ‘complete change of attitude’ and the ‘180% [sic!] alteration in Czechoslovak policy’ in favour of Germany. Hitler told Chvalkovský that, at that moment, Czechoslovakia had two choices: a settlement with the Reich ‘in a friendly manner’, or the adoption of a hostile attitude, which would inevitably lead to a ‘catastrophe for the country’. He made it clear that he wished to leave the settlement of the future border to further Czech–Hungarian negotiations.5 In his meeting with Darányi he expressed his dissatisfaction with Hungary’s passive attitude during the Sudeten crisis;6 indeed, he and Ribbentrop were to criticize Hungary frequently during the coming months.7 Apart from that, he told his Hungarian guest that he wanted to keep out of the territorial disputes between the two countries. By contrast, during his first meeting with the Slovak Prime Minister, Tiso, Ribbentrop expressed strong German support for Slovak autonomy.8

After it proved impossible to settle the issue of the border between Hungary and Czechoslovakia in bilateral negotiations, the governments of the two countries decided to submit themselves to the arbitration of the two Axis powers, Italy and Germany. Hitler was unenthusiastic, but suppressed his doubts probably because, at the time, he was trying to get Italy to join a three-power pact. On 2 November, the so-called Vienna Accord was announced, involving the cession of territory that hitherto had been part of Slovakia and Carpatho-Ukraine to Hungary. Hitler left it to Ribbentrop and Ciano to make peace between Slovakia and Hungary in Schloss Belvedere in Vienna.9 When, in the middle of November, Hungary attempted a military occupation of the whole of Carpatho-Ukraine, Hitler forced the Hungarians to call it off. The Hungarian occupation of Carpatho-Ukraine would ‘humiliate the Axis powers . . . whose arbitration Hungary had accepted without reservation three weeks ago’.10

It appeared at first as if Munich would bring Poland and Germany closer together as beneficiaries of the defeat of Czechoslovakia. The cooperation begun between the two countries in 1934 had borne fruit as far as the Nazi regime was concerned and ought to be intensified. On 24 October, acting on Hitler’s instructions, Ribbentrop had received ambassador Lipski in Berchtesgaden in the presence of Walter Hewel, his liaison with the Reich Chancellery, in order to propose a ‘general settlement’ of German–Polish relations.11 He made the following proposals: Danzig should be returned to the Reich, in compensation for which Poland would receive a series of concessions in the Danzig region; an extra-territorial railway line and autobahn should be built through the Corridor; the two countries should guarantee each other’s borders; the German–Polish treaty of 1934 should be extended; and Poland should join the Anti-Comintern pact. Initially, Lipski responded only to the question of Danzig: an Anschluss with the Reich was ruled out for domestic political reasons alone.12 This was confirmed by the Polish government in their official response, which Lipski passed on to Ribbentrop on 9 November. Instead, the Warsaw government proposed that the League of Nations statute should be replaced by a Polish–German agreement, underpinning the status of Danzig as a free city.13

Poland’s negative response convinced Hitler of the urgent need to secure a closer alliance with Italy and Japan. Responding to initial Japanese feelers put out in June, Ribbentrop had used the Munich conference to liaise with Ciano in pursuing a German–Italian–Japanese pact, behind the backs of Chamberlain and Daladier. This was intended to represent a firming up and expansion of the Anti-Comintern Pact, of which Italy had been a member since 1937.14 During Ribbentrop’s visit to Rome in October, Mussolini had given his approval in principle to this idea,15 and, at the beginning of January, Ciano indicated that Mussolini was prepared to sign it. While in Rome, Ribbentrop had explained to Ciano that the alliance reflected Hitler’s view that ‘in four to five years’ time armed conflict with the western democracies must be considered to be within the realms of possibility’.16 Ciano concluded that Ribbentrop was heading for a war in three or four years’ time under the cover of his proposed defensive alliance. Originally, the agreement was to be signed in January 1939, but this was prevented by the Japanese, who initially blamed communication problems,17 and then sent a committee of experts to Europe to discuss further details.18

At the end of November, Hitler had issued detailed directives for ‘Wehrmacht discussions with Italy’. The idea was to prepare the basis for a joint war against France and Britain ‘with the aim of initially crushing France’ – Hitler’s first outline of the later ‘western campaign’. However, when the discussions first got started some months later, Hitler issued new instructions, involving a much more general exchange of information rather than the working out of a common war plan. He wanted to conceal from the Italians that he had no intention of launching a war in three or four years’ time, but rather aimed to do so at the next available opportunity, dragging Italy into this war through another surprise move.

A further increase in rearmament

Immediately after the Munich agreement, Hitler ordered a further exceptional increase in rearmament, a sign of his deep frustration that he had been forced to accept ‘the salvation of peace’. General Georg Thomas, chief of the Wehrmacht rearmament programme, informed his armaments inspectors some time later that, on the same day as Munich, he had received a directive to concentrate all preparations on a war against Britain, ‘Deadline 1942’.19

On 14 October, Göring announced to a meeting of the General Council of the Four-Year Plan, which coordinated the work of the various ministries involved, that Hitler had directed him ‘to carry out a gigantic programme that will dwarf what has been achieved so far’. He had been assigned ‘by the Führer the task of hugely increasing rearmament, with the main focus on the Luftwaffe. The Luftwaffe had to be quintupled as fast as possible. The navy too had to rearm faster, and the army had rapidly to acquire large quantities of offensive weapons, in particular heavy artillery and heavy tanks’. But priority should also be given to ‘chemical rearmament’, in particular fuels, rubber, gunpowder, and explosives. In addition, there was the need for ‘accelerated road construction, canal improvements and, in particular, railway construction’. Moreover, the Four-Year Plan had to be revised in two ways: ‘1. All building work to do with rearmament should be prioritized, and, 2. Facilities had to be created that really saved foreign exchange’. Göring stated that he was confronted with unexpected difficulties, but, ‘in order to achieve this goal, if necessary he would turn the economy round using the most brutal methods. . . . He would make barbaric use of the general powers the Führer had assigned him.’20

In the second part of his speech on 14 October, Göring talked about the ‘Jewish problem’. He considered the expropriation of Jewish property as undoubtedly one of the ways of resolving the economic difficulties: ‘The Jewish question had now to be tackled with every means available, for they had to be excluded from the economy’. However, he totally rejected a ‘free-for-all commissar economy’, as had occurred in Austria, where Party members had simply arrogated to themselves the right to take over Jewish property. For ‘Aryanization’ was nothing to do with the Party, but ‘solely a matter for the state. However, he was not in a position to make foreign exchange available for deporting Jews. If necessary, ghettos would have to be established in the larger cities.’

Hitler’s decision to increase rearmament, as reported by Göring, prompted the propaganda ministry and OKW to launch a major campaign ‘to make the Wehrmacht popular’. Using a combination of media, ‘the people’s confidence in their own strength and in Germany’s military power was to be enhanced’.21

Hitler combined his directive for a further exceptional increase in rearmament with concrete political goals. During October, he made frequent brief visits to the recently occupied Sudeten territories, in order to receive applause, visit Wehrmacht units, and inspect the Czech fortifications.22 On 21 October, he directed the Wehrmacht to set itself three tasks for the immediate future:

As far as ‘liquidating the remainder of Czechoslovakia’ was concerned, preparations ‘were to be made already in peacetime and geared to a surprise attack so that Czechia has no opportunity for a planned response’.23

Pogrom: ‘The Night of Broken Glass’

Immediately after the signing of the Munich agreement, a strong anti-Semitic mood developed once more among Party activists. It followed on from the anti-Jewish excesses of summer 1938, for which Goebbels’s Berlin campaign had been mainly responsible, but which had been suppressed by the regime during September for diplomatic reasons.

Now, in October 1938, Party activists evidently intended to find a scapegoat for the mood of depression that had spread throughout the Reich during September as a result of the threat of war. Once again, ‘the Jews’ would have to bear the brunt of the Party members’ frustration. After the conclusion of the Munich agreement diplomatic concerns no longer applied, and so anti-Jewish excesses could begin again: Jewish shops and synagogues were daubed with graffiti and destroyed.24 According to the SD, during October, a real pogrom atmosphere developed among Party activists.25 However, this was by no means a spontaneous unleashing of emotion on the part of radical anti-Semites; it chimed in exactly with the policy the SD itself had been pursuing since the summer of 1938.

In response to the massive expulsion of Jews from Germany and, in particular from Austria after the Anschluss, in July 1938, an international refugee conference had been convened in Evian on the initiative of President Roosevelt. However, it had only revealed the unwillingness of participant countries to admit large contingents of Jewish refugees. The sole concrete result had been the creation of an Intergovernmental Committee on Political Refugees, which was supposed to work out future arrangements in consultation with Germany. This enabled Germany to turn the expulsion of Jews from the Reich into a ‘problem’ requiring an international solution.26 Thus, there was an incentive to speed up expulsions in order to put pressure on the Committee to act.

In the meantime, Adolf Eichmann, the SD’s desk officer for Jewish affairs appointed to deal with Jewish matters in Austria, had developed a scheme for accelerating Jewish expulsion. With the aid of Bürckel, in August he established a ‘Central Agency for Jewish Emigration’, through which the chaotic Jewish persecution in Austria was turned into an ‘orderly’ process for the comprehensive economic plundering and expulsion of the Jews.27 For this procedure to be adopted throughout Germany, however, a new anti-Semitic ‘wave’ was required, a spectacular radicalization of Jewish persecution that would necessitate a Reich-wide reorganization of persecution and expulsion.

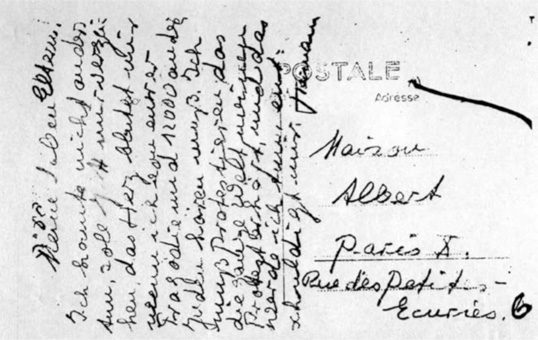

This was already happening at the end of October. On 26 October, Himmler ordered the expulsion of Polish Jews living in Germany. During the coming days, 18,000 people were arrested and driven over the Polish–German border, the first mass deportation of the Nazi era. On 7 November, 17-year-old Herschel Grynszpan shot the German diplomat, Ernst vom Rath, in Paris in revenge for the expulsion of his parents from Germany, thereby offering the regime a welcome pretext for unleashing a pogrom.28

Figure 8. On 6 November Herschel Grynszpan wrote a final postcard to his parents: ‘Dear parents, I had to do it, may God forgive me. My heart bleeds when I hear of the tragedy you and 12,000 other Jews have suffered. I simply have to protest and make the whole world take notice of my protest, and that’s what I intend to do. Forgive me. Hermann’

Source: akg-images

On 7 November, the same day as the assassination attempt, the German propaganda media began a campaign, in which Grynszpan was declared to be the tool of an international Jewish conspiracy. The assassination of Gustloff by Frankfurter in 1936 was naturally portrayed as a prior example.29 During the night of 7/8 November and on the following day, Party activists in the Kassel area (a traditional centre of German anti-Semitism) carried out large-scale attacks on Jewish businesses and synagogues. This campaign was probably launched by the Gau propaganda chief.30 However, for these attacks to be turned into a Reich-wide pogrom against German Jews a central directive was required, and that, as was always the case when the regime’s so-called Jewish policy was to be radicalized, could come only from Hitler.

Goebbels, one of the most important hard line anti-Semites, made a significant contribution towards preparing the way for this and he had personal reasons for doing so. A serious crisis in his marriage, caused by his affair with the actress Lída Baarová had damaged his relationship with Hitler, and he also wanted the differences of opinion he had had with Hitler over the Sudeten crisis to be forgotten. For Goebbels had not only been among those who wanted to avoid a war at all costs, but had made no secret of his unwillingness to use his propaganda machine to overcome the population’s lack of enthusiasm for war. Now, as Party activists in the provinces once again began large-scale attacks on Jews, Goebbels saw the chance radically to change the image of an all too ‘peace-loving’ German population through a Reich-wide pogrom. And here Goebbels’s desire to rehabilitate himself coincided with the intentions of the Jewish persecutors in the SD and SS, as well as with Hitler’s own. During these weeks, the ‘Führer’ was trying to find an issue that would enable him to bring about a fundamental change in the Third Reich’s public persona, a shift towards maximum solidarity, ideological radicalism, and readiness for war. An open eruption of a hitherto inconceivable degree of anti-Jewish violence would provide him with the platform for this fundamental reorientation. He calculated that this would cause a panic-stricken flight of Jews from Germany, with the international community coming under pressure to take them in. Moreover, the most radical expulsion possible of Jews from Germany would, as with Austria, offer the prospect of rapidly acquiring Jewish property, thereby alleviating the Reich’s precarious foreign exchange and financial position.

Thus, Hitler launched a pogrom against the Jews from a variety of very different motives and interests. His decision to step up the radicalization of Jewish persecution can be seen – following 30 June 1934, the Nuremberg laws of 1935, the switch to the Four-Year Plan in 1936, and the solution of the Blomberg–Fritsch crisis in 1938 – as one more stage in the history of his dictatorship, one of those situations in which he allowed a complex crisis to come to a head, so that he could then intervene in a spectacular way and apparently reorder it, focusing attention on an issue he could use to dominate the political agenda during the following weeks.

On the evening of 8 November, participants in the failed 1923 putsch, together with Party bigwigs, gathered in the Bürgerbräukeller, as they did every year, in order to take part in the traditional commemorative march the following day. Meanwhile, the anti-Jewish press campaign was continuing.31 In addition, during the course of the day more reports were coming in of anti-Jewish riots in Kassel and Dessau.32 In the late afternoon of the following day, while staying in his flat in Prinzregentenplatz, Hitler received the news that vom Rath had died of his injuries.33 That evening, the usual celebrations took place in Munich’s old town hall and, on the sidelines, Hitler conferred with Goebbels, who later noted the following in his diary: ‘I explain the matter to the Führer, He decides: “Let the demonstrations continue. Withdraw the police. For once the Jews’ll feel the people’s anger.” That’s as it should be. I immediately give appropriate instructions to the police and the Party. Then I speak briefly along those lines to the Party leadership. Storms of applause. Everyone dashes straight off to telephone. Now the people will act.’34

Hitler had left the town hall before Goebbels’s speech, but it is clear from Goebbels’s note that it was Hitler who gave the go ahead for the pogrom. However, it was up to Goebbels to inform the Party leadership of the decision in his harangue and, during the next few hours, to take the lead as a hardliner, so that many people considered him responsible for the pogrom. This distribution of roles was fully intended by Hitler, who remained very much in the background during the events that followed.

During the night, high ranking Party functionaries, Gauleiters, SA Gruppenführer, and the like, urged on by Goebbels, unleashed the pogrom in hundreds of towns and cities. Party members and SA men in civilian clothes, who, throughout the Reich, had been meeting to commemorate 9 November, now went about destroying synagogues, setting them on fire, smashing the windows of Jewish businesses, and plundering shops; they gained forced entry to Jewish flats, destroying the furnishings, stealing items of value, mistreating and dragging off their inhabitants.35 Shortly before midnight, the Gestapo received instructions to prepare for the arrest of 20,000 to 30,000 Jews, an order that came directly from Hitler.36 These mass arrests of more than 30,000 people took place on 10 November; the vast majority of victims, over 25,000, were placed in concentration camps, where most of them remained incarcerated for weeks or months while being subjected to cruel mistreatment.37 It is not known how many died from this violence; the official number of dead was given as 91.38 However, there were a considerable number of suicides, as well as hundreds of Jews who, during the following weeks and months, were murdered in concentration camps or were to die from the effects of their imprisonment.39

While the pogrom was raging in Munich, as in many other cities, Hitler remained in his flat in the Prinzregentenplatz.40 Around midnight, he joined Himmler in attending the annual swearing-in of recruits for the armed SS and the SS Death’s Head units at the Feldherrnhalle, while the city’s synagogues were burning. The fact that Hitler did not refer to these events in his address to the recruits is another example of his attempt to distance himself from the violence.41 At midday on 10 November, Hitler met Goebbels in his favourite Munich restaurant, the Osteria Bavaria in Schellingstrasse. He approved a draft prepared by the propaganda minister for an official announcement that ‘all further demonstrations and acts of retribution against the Jews’ were to cease immediately.42 Clearly, the whole campaign was threatening to get out of control. Hitler informed Goebbels about the next important anti-Semitic measures: ‘They must put their businesses in order themselves. The insurance companies won’t pay them anything. Then the Führer wants gradually to expropriate Jewish businesses and give their proprietors bits of paper that we can devalue at any time.’

Hitler then received 400 representatives of the press in the Führer building on Königsplatz, in order to provide them with a certain amount of essential background information about his policies and to initiate a decisive change in the focus of propaganda.43 Hitler explained to the journalists that he had hitherto been forced ‘for years almost solely to speak of peace’. This had been the only way he had been able to achieve his foreign policy successes. This ‘peace propaganda that had been going on for decades’ had, however, given the people the false impression that he wanted ‘peace at all costs’. To remove this mistaken impression, months ago he had begun ‘gradually to make clear [to the people] that there are things . . . which have to be achieved by force’. The propaganda media would have to do more to reflect this point of view.44

Thus, while in this speech Hitler was making clear his discontent with the German population’s lack of readiness for war that had become apparent a few weeks earlier, he was using the unprecedented mobilization of force during the previous thirty-six hours as a platform for the transition to overt war propaganda. This change of course was not, however, intended to happen abruptly, but in stages. Hitler’s next big speeches, beginning with his Reichstag speech of 30 January 1939, were to set the new tone. To start with, anti-Semitism was to be a main propaganda theme; the subsequent justification of the pogrom was intended to mark the shift in the process of getting the population ready for war, a war that was to be directed not merely at the western powers but also against a ‘Jewish world conspiracy’. For, as with the hurried preparations for war at the end of September, in general the German population had not approved of the pogrom. In particular, the violence and destruction of 9 November had prompted widespread disgust and censure, although these sentiments were not as a rule openly expressed. Ultimately, the events had been accepted. However, it was precisely this passive attitude, often rooted in indifference, which was to be overcome by a more aggressive tone in propaganda, now concentrated on mobilization.45

During the following days, Hitler gave his express support to the Propaganda Ministry’s anti-Semitic press campaign,46 which focused above all on the middle class, whose response to the regime’s violent Jewish policy had been distinctly unenthusiastic.47 It continued into January 1939, although it began to face difficulties and lose momentum.48 A campaign of Party meetings to ‘enlighten the whole population about Jewry’ was even intended to go on until March, an indication that the alleged ‘popular anger’ against the Jews needed considerable propaganda to stoke it.49

On 12 November, while the propaganda campaign to justify the pogrom was getting under way, over 100 representatives of the Party, the state, and economic organizations gathered in the Reich Air Ministry to consider, under Göring’s chairmanship, how the further persecution of the Jews was to proceed. It was no accident that it was Göring who now took on the leading role in clearing up the mess left by the ‘Night of Broken Glass’ [Reichskristallnacht], and producing ‘orderly policies’. Right from the start, the expropriation of Jewish property had been one of the basic objectives of the Four-Year Plan, for which, in 1936, Hitler had made Göring responsible. The meeting agreed on a legal ‘solution’, which was precisely in line with Hitler’s requirements. As an ‘atonement fine’ for the death of vom Rath, Jews were to be forced to pay a billion RM (as Hitler had demanded in his Four-Year Plan memorandum of 1936). Also, as Hitler had told Goebbels in the Ostaria Bavaria on 10 November, they were to be excluded from German economic life, their insurance claims for the damage caused were to be confiscated by the state, and they were to be compelled to repair all damage immediately.50 During the coming weeks, a large number of other anti-Semitic regulations were issued.51 Moreover, Göring announced at the meeting that Hitler wanted ‘finally to take a diplomatic initiative, first of all vis-à-vis the powers who were raising the Jewish question’, in order then to move on towards a resolution of the ‘Madagascar question’. He had explained all that to him on 9 November. Hitler wanted to tell the other states: ‘Why are you always talking about the Jews? Take them!’52

Nearly, four weeks later, on 6 December, Göring had another substantial meeting with the Gauleiters, Reich Governors, and provincial presidents, in which he explained to them the most recent guidelines for Jewish policy, which the ‘Führer’ had given him a few days earlier, and whose implementation Hitler wished him to oversee, without his role becoming public. Göring’s reputation should not be compromised too much at home and abroad. Hitler’s concern about the former’s prestige indicates why he himself did not want to be associated with the implementation of the anti-Jewish measures that were to follow. However, it was in fact Hitler who determined the future development of Jewish policy right down to the details. The main emphasis, as Göring explained once again on 6 December, was above all on ‘vigorously pushing emigration’.53

As the regime had intended, the pogrom provoked a wave of Jewish emigration from Germany. Hitler was working on the assumption that this panic-stricken flight would put pressure on potential immigration countries that during the Evian conference were still refusing to admit more Jews. When, on 24 November, the South African defence and transport minister, Oswald Pirow, visited Hitler at the Berghof, in order, among other things, to offer his services as a mediator for an international solution to the German ‘Jewish question’, the ‘Führer’ told him that the ‘Jewish problem’ ‘would soon be solved’; this was his ‘unshakeable will’. It was not only a ‘German’, but also a ‘European problem’. Hitler went so far as to issue an open threat: ‘What do you think would happen in Germany, Herr Pirow, if I were to stop protecting the Jews? The world couldn’t imagine it.’54

At the beginning of December, concrete steps were taken to turn the wave of Jewish emigration into a systematic policy of expulsion. These measures derived from Hitler’s directives, as is clear from Göring’s statements of 12 November and 6 December. At the start of December, building on an idea of the Austrian Economics Minister, Hans Fischböck, Schacht put forward a plan to finance Jewish emigration through an international loan, which would be guaranteed by the property left behind in Germany by Jewish emigrants and paid off by granting relief for German exports.55 Hitler accepted this proposal,56 and, in January, Schacht began negotiations with the chairman of the Intergovernmental Committee for German Refugees, George Rublee.57 However, this truly fanciful plan was not put into effect, as negotiations were pursued only half-heartedly by all those involved.58 During 1939, however, a number of countries, including Britain and the United States, indicated that they would be willing to take larger contingents of Jewish refugees.59

At the end of 1938/39, in order to increase the pressure to emigrate, the regime concentrated on trying to restrict Jewish life as far as possible. At the meeting on 6 December, Göring had, among other things, announced a number of concrete decisions by Hitler relating to Jewish policy. According to Göring, Hitler had set priorities for ‘Aryanization’: Jews were to be expropriated, in particular where they represented an obstacle to the ‘country’s defence’. Hitler also decided that Jews should not be visibly labelled, an issue that had been discussed in the meeting of 12 November, because he feared anti-Jewish excesses.60 There should be no prohibitions on selling to Jews; however, Jews could be banned from entering certain localities. Göring then made clear his determination to continue to hold a certain percentage of Jews hostage: ‘I shall not permit certain Jews, whom I could easily allow to emigrate, to do so, because I need them as a guarantee that the other riff raff* abroad will also pay for the Jews without means.’61

On 28 December, after a meeting with Hitler, Göring announced to senior Party and state officials another binding Führer decision concerning further anti-Jewish measures.62 In accordance with this list, during the coming months a further wave of discriminatory provisions was issued. Thus, in response to Hitler’s wishes, Jews were forbidden to use sleeping and dining cars,63 rental protection for Jews was substantially suspended,64 and Jews were largely prohibited from staying in seaside resorts and spas.65 During the first months of 1939, there were a considerable number of additional measures.66 The main focus was on the complete ‘Aryanization’ and expropriation of Jewish property. When it became clear that they could not all be rapidly expelled, there was a move towards the imposition of forced labour and restrictions on their freedom of movement and housing, with a clear trend towards ghettoization. All in all, German Jews were being subjected to a coercive regime, while in the event of war their incarceration in camps was being considered the appropriate ‘intermediate solution’ to the ‘Jewish question’.67

Economic bottlenecks

In November 1938, Hitler and the regime’s leadership began to deal with the impact of the ‘Führer’s’ order, issued after the Munich conference, for an enormous expansion of the rearmament programme.68

At first, it appeared as if, for the first time, Hitler wanted to try to place his rearmament plans on a more realistic basis. On 11 November, at any rate, Keitel informed the Wehrmacht branches that, after hearing from their respective commanders-in-chief, Hitler intended ‘to organize rearmament organically in accordance with uniform principles and priorities, using a timespan of several years, and to bring it into line with the available resources in men, raw materials, and finance’.69 On 18 November, at the first meeting of the Reich Defence Council, created in September 1938 by statute, Göring as chairman gave a lengthy statement supposedly inaugurating this new course.70 This was a committee intended to coordinate the war plans of the various ministries. Göring, working on the basis of a tripling of the rearmament programme, put forward a maximum programme for the civilian sector covering a range of areas.: expansion of the transport system; an increase in agricultural production; more exports to improve the foreign exchange situation; an increase in industrial production, above all through rationalization; an austerity programme to sort out the financial situation, which looked ‘very critical’; cutbacks in the administration; a rigorous wage freeze; and the comprehensive control of all labour resources. This was designed to make such an enormous increase in armaments production feasible.

A few days and weeks after the meeting, the first measures were introduced:71 a revision of price controls, aiming to reduce excessive profits from armaments contracts;72 the appointment of Colonel Adolf von Schell as General Plenipotentiary for Motor Transport, whose task it was to introduce standardization throughout the motor industry;73 and, finally, the appointment of Fritz Todt as General Plenipotentiary for the whole of the construction industry.74

In the meantime, however, the armaments’ plans of the individual armed forces had long since begun to go their own way. Since October, the Luftwaffe had been planning a new construction programme that aimed to build over 30,000 aircraft by spring 1942, in order to achieve a total of 21,750 combat-ready aircraft (excluding reserve, training, and test aircraft).75 The deadline was then slightly extended, but the plan was retained: around 30,000 aircraft were to be built by 1 April 1942, which, given the industrial capacity and raw materials available, was completely unrealistic.76

The navy had similar gigantomaniacal plans. Responding to Hitler’s demand, already issued in May 1938, for increased armaments, a naval planning committee convened in August produced a plan at the end of October envisaging a fleet of 10 battleships, 15 pocket battleships, 5 heavy, 24 light and 35 small cruisers, 8 aircraft carriers, and 249 submarines. This represented a considerable increase compared with the old construction plan of December 1937, which, for example, had included only 6 battleships and 4 aircraft carriers.77 Hitler approved the plan on 1 November, but demanded that the construction of the battleships should be accelerated to be ready by 1943. The navy chief, Admiral Raeder, produced a new schedule on this basis, the so-called Z programme, and put it to Hitler at the end of January 1939. Hitler then ordered the construction of six battleships by 1944, giving the navy priority over the other armaments’ programmes as well as exports. Raeder, however, declared that he would not need this fleet before 1946.78 According to a calculation by the economics department of the Naval High Command (OKM), the fuel requirement for the Z fleet when completed would be larger than the total German annual consumption of oil products.79 These plans greatly exceeded the limits laid down in the Anglo-German Naval Agreement. Hitler’s abrogation of the agreement in April 1939, which we return to below, was in response to advice from the naval High Command.80 Raeder assumed that, with the completion of this plan, from 1942 onwards the navy would be in a position to fight a large-scale submarine war and, from the end of 1944, with its large ships would ‘even be a serious opponent for a major naval power such as Great Britain’.81

The new armaments’ programmes resulted in a massive expansion of the Wehrmacht’s budget. In November, a memorandum by the OKW’s liaison officer with the Economics Ministry and the Reich Bank estimated that, since 1934, 38.9 billion RM had been spent on rearmament, in other words already around 4 billion RM more than had been planned in 1934 for the next four years. The budget for 1939 had a deficit of over 8 billion RM.82 There was such an urgent demand for exports in order to acquire foreign exchange that, on 9 November, the Wehrmacht economics staff were compelled to inform the Wehrmacht branches that industry had been instructed to give priority to export contracts, including those for machine tools and armaments, over all domestic orders. This also applied to the Wehrmacht itself.83 During the final months of 1938, in view of a deficit amounting to billions, the Finance Minister found himself confronted with the alternative of either declaring bankruptcy or printing money.84

Thus, at the beginning of December, Hitler was obliged to inform the commanders-in-chief of the three Wehrmacht branches that ‘the Reich’s tense financial situation’ made it necessary to reduce the Wehrmacht’s expenditure until the end of the financial year (31 March 1939). All Wehrmacht branches should give priority to the acquisition of weapons systems over munitions.85 In February, Brauchitsch was forced to inform Hitler in two ‘reports’ that, as a result of the cuts and the ban on issuing new contracts in the steel sector, he would be unable to meet the army’s armaments’ targets.86 However, the naval Z Plan was to be exempted from these cuts in accordance with Hitler’s January order.

In January 1939, after Schacht had given various warnings of the danger of inflation during autumn 1938,87 the Reich Bank directorate sent a memorandum to Hitler. It stated that the ‘foreign exchange and financial situation’ had ‘reached a danger point, requiring urgent measures to avert the threat of inflation’. ‘The unlimited expansion of government expenditure is ruling out any attempt at achieving a balanced budget, and, despite a huge increase in taxes, is bringing the nation’s finances to the brink of collapse, thereby undermining both the Reich Bank and the currency.’ It was vital, in order to avert the threat of inflation, that new expenditure should be financed solely through taxes or loans (but then only if these did not disturb the long-term capital market). The whole of the financial sector must be put under the strict control of the Reich Finance Minister, the Reich Bank, and the Reich Prices Commissioner.88 Two weeks later, Hitler dismissed Schacht.89 With his departure all restrictions on the increase in the money supply disappeared.90

Visits from foreign statesmen

While the anti-Semitic propaganda campaign continued uninterrupted, in January Hitler received the foreign ministers of Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia on the Obersalzberg, in order to prepare his further expansion plans. The uninhibited manner in which he discussed the ‘Jewish question’ during these meetings demonstrates the close connection that in Hitler’s view existed between expansion and the further radicalization of Jewish persecution.91 Before the meetings began, Hassell, the former German ambassador in Rome, had learnt from state secretary Weizsäcker during a visit to Berlin in the middle of December that German foreign policy was moving towards war; it was only a question of whether they should move straight away against Britain and secure Polish neutrality, or whether they should ‘act first in the East to deal with the German–Polish and Ukrainian questions’. That was precisely the issue that Hitler wanted to clarify with the Poles in January.

During the meeting with the Polish foreign minister, Beck, on 5 January, the main focus was above all the future of Carpatho-Ukraine, where a government had established itself with German support and was pursuing a pronounced ‘greater Ukrainian’ policy, in other words the aim of creating the core of a future Ukrainian state to include the Ukrainians in the Soviet Union as well as those in Poland.92 This alarming prospect was sufficient reason for Beck to advocate the territory being joined to Hungary.

In his reply Hitler began by emphasizing that ‘nothing whatsoever had changed’ in Germany’s relations with Poland since the 1934 Non-Aggression Pact. As far as the Carpatho-Ukraine issue was concerned, he could assure him that, with reference to ‘the intentions ascribed to Germany in the world press’, Poland had nothing at all to fear. With his mention of ‘ascribed intentions’ Hitler was referring to speculations in the British and French press that Germany was planning to use Carpatho-Ukraine as a springboard for further conquests in the east.93 In fact, Hitler stated, the Reich had ‘no interests beyond the Carpathians’. He then raised the question of Danzig and the Corridor. He told his Polish guest that he was thinking in terms of a formula whereby ‘Danzig would belong politically to the German community, but would remain economically with Poland’. Danzig was after all ‘German, would always remain German, and would sooner or later join Germany’. If Poland agreed to Danzig returning to the Reich and if ‘entirely new solutions’ could be applied to settle the problem of the link with East Prussia – Hitler was referring to the project for extraterritorial transport links through the Corridor – then he was prepared to guarantee Poland’s borders through a treaty. Beck took note of Hitler’s wishes with regard to Danzig, but added that this question ‘seemed to him extremely difficult’.

Hitler then raised another issue ‘in which Poland and Germany had common interests’, the ‘Jewish problem’. According to the minutes, he said that he was ‘determined to get the Jews out of Germany . . . if the western powers had shown more sympathy for Germany’s colonial demands, he might have . . . provided a territory in Africa that could have been used for settling not only the German, but also the Polish Jews’.94

The following day Ribbentrop once again set out Germany’s list of proposals: ‘Return of Danzig to Germany’, ‘guaranteeing all Poland’s economic interests in the Danzig region as well as an extraterritorial link through the Corridor; in return: recognition of the Corridor by Germany and permanent mutual recognition of their borders’. However, Ribbentrop mentioned another point on which he made himself much clearer than Hitler had done. He could imagine that, if these problems could be satisfactorily resolved, Germany would be willing ‘to regard the Ukrainian question as a matter for Poland and to give it its full support in dealing with this question. However, this would involve Poland adopting a very clear anti-Russian position, since otherwise their interests would hardly coincide’. In this context Ribbentrop returned once more to the question of Poland’s adherence to the Anti-Comintern Pact. Beck, however, had no intention of committing himself to a common policy towards the Soviet Union.95

Beck continued to stick to this position when Ribbentrop travelled to Warsaw at the end of January, in order to renew the German ‘offer’ of a settlement of the Danzig/Corridor issue together with a common approach to the Soviet Union and Poland’s annexation of the Soviet Ukraine.96 However, the Polish foreign minister was not prepared to make any concessions involving the subordination of his country to a risky alliance policy dictated by Germany.

Thus, the project for a joint war against the Soviet Union, which Germany had been proposing to Poland for years, had finally collapsed. Hitler, however, had already made clear to Beck that his regime did not need Poland’s cooperation in order to use Carpatho-Ukraine to form the nucleus of a Ukrainian state. As we have seen, Germany had frequently revealed this ambition during the preceding weeks and months, and it had preoccupied not only the international press, but also neighbouring states. Both King Carol II of Romania and the Hungarian Regent, Horthy, had already spoken to the German government about its plans for Ukraine.97 At the end of January 1939, Goebbels learnt from Hitler that he wanted to spend time on the Obersalzberg ‘reflecting on his next diplomatic moves. It might be Czechia again, for this problem has only been half solved. But he’s not quite certain. It might also be the Ukraine.’98

If Hitler was still contemplating taking over the Ukraine in whatever form, it indicates that at this juncture he was already considering the prerequisite for this step, namely the crushing of Poland. It is possible that he thought that, by attacking Poland, he could prompt the Ukrainian minority to start an uprising and, with solid German backing, extend it into the Soviet Ukraine. In any case, at this point he certainly did not have a concrete plan. His comment to Goebbels, however, shows that, apart from destroying Czechoslovakia, he was contemplating other options of how to reorder the political landscape of eastern Europe, now in flux, and believed that the issue of Carpatho-Ukraine could be exploited vis-à-vis Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, and Romania, as well as the Soviet Union. This is a good example of the extent to which Hitler’s foreign policy, particularly during this critical phase, was marked by multiple approaches and an unwillingness to commit himself, in short by an intentional unpredictability.

On 16 January, he rebuked the Hungarian foreign minister, Count István Csáky, for his government’s behaviour during the Sudeten crisis and for its attempt in November, despite the Vienna Award, to take over Carpatho-Ukraine. However, Hitler was magnanimously prepared to give Hungary a second chance to prove itself a loyal ally by participating in the final destruction of Czechoslovakia, a move which would involve departing from ‘ethnographic principles’. Now that the German, Hungarian, and Polish claims on Czechoslovakia, based on bringing home the respective minorities, had been met, another justification had to be found, a ‘political-territorial one’, for forcibly occupying and directly subjecting it to his rule.99 In the second half of December, Hitler had rejected a treaty that had been prepared in the Foreign Ministry following the Munich Conference with the aim of subordinating Czechoslovakia to the Reich.100 He was not interested in a dependent relationship based on a treaty.

On 21 January, Hitler once again received the Czechoslovak foreign minister, Chvalkovský, whom he also berated. The Czech state had not carried out a thorough purge of Beneš supporters; it had not come to terms with the fact that Czechoslovakia’s fate was now indissolubly linked to Germany’s. He bluntly announced that ‘if there was a change of course its first result would be the destruction of Czechoslovakia’.101 Two days later, Ribbentrop also gave Chvalkovský a long list of German complaints.102 This was clearly intended as a ‘last warning’, which, when the time came, would have to serve as justification for a German attack on Czechoslovakia.

Hitler also referred to the ‘Jewish question’ in his discussions with Csáky and Chvalkovský, who did not remain silent. Csáky asked whether this question could not be ‘solved internationally’; Romania had contacted him about reaching a common solution. Hitler responded by outlining Germany’s plan ‘to solve this problem through a financial scheme’. He was, however, clear about the fact that every last Jew had to disappear from Germany.103 Chvalkovský was told: ‘Our Jews will be annihilated. The Jews did not perpetrate 9 November 1918 for nothing; this day will be avenged.’ Hitler’s subsequent comment that ‘the Jews were poisoning the people’ in Czechoslovakia as well prompted his guest to launch into a lengthy anti-Semitic diatribe.104

The threat of ‘annihilation’ evidently did not mean the physical destruction of the Jews, but rather the end of their collective existence in Germany through expulsion. At the end of January, the responsible Reich authorities prepared for the planned negotiations between Schacht and Rublee concerning the organized emigration of the Jews soon to lead to concrete results. After a series of meetings of government representatives on 18 and 19 January,105 Göring ordered the creation of a ‘Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration’, (along the lines of Eichmann’s emigration office in Vienna) under Heydrich, and simultaneously forced all Jewish organizations to be subsumed in a new compulsory single organization. This was the origin of the ‘Reich Association of the Jews in Germany’.106

A day after the creation of the Reich Central Office, the Foreign Ministry, which had appointed a liaison officer to the new organization, informed all German missions and consular offices abroad: ‘The final goal of German Jewish policy is the emigration of all Jews domiciled in Reich territory.’107

Hitler as ‘Prophet’: War against domestic and foreign enemies

In his speech to the Reichstag to mark the sixth anniversary of the seizure of power Hitler once again took a hard line on the ‘Jewish question’. At the same time, he sketched out a war scenario similar to that in his secret speech of 10 November 1938, in which he had announced a change from talk of peace to the preparation of the population for war. The speech on 30 January 1939 marks the culmination of the anti-Semitic propaganda following the November pogrom and, at the same time, the point at which Hitler began to prepare the population for a war that might arise from the confrontation with ‘Jewry’ at an international level.

He began by dealing in detail with the negotiations concerning the organized expulsion of the Jews, joking about the ‘democracies’’ lack of enthusiasm in accepting Jews; Germany, at any rate, was absolutely determined ‘to get rid of these people’. After heaping scorn on the Jews, he came to the core of what he had to say. The following statements were influenced to a considerable extent by feelings of inferiority rooted deep in the past and a resultant unsatisfied desire for revenge. He had, he said, in the course of his life, ‘very often been a prophet and was generally laughed at for it’, in particular by ‘the Jewish people’, who ‘simply laughed at my prophecies that I would one day assume the leadership of the state and thereby of the entire people and then, among many other things, achieve a solution of the Jewish problem. Their laughter was uproarious, but I think that for some time now the Jews in Germany have been laughing on the other side of their faces. Today, I want to be a prophet once again: if international Jewish financiers inside and outside Europe should succeed once more in plunging the nations into a world war then the result will be not the Bolshevization of the world and therefore the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.’

Was Hitler announcing publicly and to the whole world his intention to murder the Jews in a coming war? At this juncture, the word ‘annihilate’ cannot be unequivocally interpreted in this sense. A few days earlier, Hitler had also spoken to the Czech foreign minister about ‘annihilating’ the Jews, but had meant their expulsion, quite apart from the fact that he had also warned Chvalkovský of the ‘annihilation’ of Czechoslovakia. When interpreting this passage, as with many other Hitler statements, one should be aware that Hitler was not simply announcing a decision taken in isolation, but rather that his ‘prophecy’ had several potential layers of meaning. Above all, in the first place, one must take into account the tactical motive of his speech, which should be seen in the context of the international negotiations concerning Jewish emigration.

His annihilation threat was intended, first of all, to increase the pressure on German Jews to emigrate and on foreign countries to receive them. Secondly, the announcement that the Jews in the German sphere of influence in Europe would be annihilated in the event of a world war was part of a long-term strategy for assigning blame for the outbreak of an impending war. When Hitler claimed that ‘international Jewish financiers’ within and outside Europe might attempt to bring about a world war (and not simply a war), the main target audience of his prophecy was the United States. He was contemplating a scenario in which the western powers, supported by the United States, could intervene in order to prevent him from continuing his expansionist policy in Europe, to which he was totally committed. In this case, blame for the war would rest unequivocally with the enemy, who had been incited by ‘international Jewish financiers’. And, thirdly, if a war begun by Germany turned into a world war as a result of intervention by the western powers, Jews within Germany’s sphere of influence would automatically become hostages over whom would hang the threat of annihilation. Thus, if his threats had no effect, if, in other words, emigration did not make much progress, and if, in the event of a war, the western powers were not deterred from intervening, then they would be responsible for the further intensification of Jewish persecution predicted in his ‘prophecy’. Thus, Hitler was keeping all options open for further radicalizing his Jewish policy.

Hitler made clear his determination to continue his expansionist policy over the medium and longer term in another section of his speech. Having not referred to it for a long time, he once again emphasized, and in a very prominent place in the speech, ‘how important the expansion of our people’s living space’ was in order permanently to secure their food supplies.108 However, since ‘for the time being [sic!] . . . on account of the continuing blindness of the former victor powers’ this expansion ‘is not yet [sic!] possible’, they were compelled ‘to export in order to buy food’, and they had to export even more in order to acquire the raw materials for those exports. However, it was clear from these words that, as far as he was concerned, this could not provide a lasting solution. At some point, his argument suggests, German living space would ‘expand’, and indeed elements within the Party were already making no bones about demanding it.109 This demand for living space, while simultaneously stressing Germany’s commitment to peace, soon became part of the standard repertoire of German propaganda, although Hitler kept a ‘statesmanlike’ distance from it.110

Apart from that, his speech contained a number of other important statements. Thus, in the section of the speech concerned with the Sudeten crisis, he admitted quite frankly that he had already committed himself to military action against Czechoslovakia on 28 May 1938 with the deadline of 2 October 1938, more clear evidence of his determination to go to war. In referring to ‘a serious blow to the prestige of the Reich’ and an ‘intolerable provocation’, he clearly revealed that the motive for this decision was his fear of personal humiliation as a result of the May crisis. But above all, he wanted to point out that the incorporation of the Sudetenland came about not as a result of diplomatic efforts, but rather the great powers had come to an agreement only as a result of his ‘determination to solve this problem one way or the other’ (in other words to risk a war).

The speech also contained a lengthy passage, also intransigent in tone, on the relationship with the Churches. Hitler threatened a complete separation of Church and state, with the inevitable serious financial consequences for both confessions, and he made it clear that clergy who were critical of the regime or abused children would be brought to book like any other citizen.111

Two weeks later, Hitler dealt with the internal and external enemies of his regime in another major speech. On 14 February, he spoke at the launch of the new battleship, ‘Bismarck’ at the Blohm and Voss shipyard in Hamburg. The prospect that in the ‘Bismarck’ the German navy would have the most powerful battleship in the world gave additional weight to his words. Hitler used the opportunity for a comprehensive assessment of the ‘Iron Chancellor’, of whose ‘little German’ [i.e. without Austria] policy he was in fact basically critical. Now, however, he celebrated him as ‘the pioneer of the new Reich’. He had created the preconditions for the creation of the present ‘Greater Germany’, as well as domestically laying the foundations ‘for the unity of the National Socialist state’. Essentially, this assessment implied that the ‘Iron Chancellor’s’ great historical achievement was to be the predecessor of Hitler, who was now completing his work. Bismarck had been the ‘creator of a German Reich . . . whose resurrection from deep distress and whose miraculous enlargement have been a gift of providence’. Dealing with domestic policy, in particular, in his speech Hitler portrayed himself as an Über-chancellor. Bismarck had been largely unsuccessful in his struggle against the ‘international powers’, ‘the politically engaged Centre Party priests’ and ‘Marxism’. By contrast, Nazism now possessed the ‘intellectual, ideological, and organizational wherewithal . . . required to destroy the enemies of the Reich, both now and in the future’.112

The occupation of Prague

At the end of January, when discussing with Goebbels whether he should move against Czechoslovakia or focus on the Ukraine, Hitler had appeared undecided. However, shortly afterwards the next foreign policy move was decided; it involved solving the ‘Slovakian question’. This was an issue that he himself did much to push forward at the beginning of 1939 and was to lead to the demise of Czechoslovakia.113 Since the beginning of the year, there had been growing collaboration with the government in Pressburg [Bratislava]114 and, on 12 February, this culminated in a meeting between Hitler and Voytech Tuka, the influential leader of the fascist wing of the Slovakian People’s Party, the most powerful political force in Slovakia, which had been autonomous since the previous autumn. Tuka was accompanied by the leader of the German ethnic group in Slovakia, Franz Karmasin. Hitler used the meeting to declare his sympathy for Slovakian demands for more independence and his mistrust of the Czechoslovak government, against which he would if necessary ‘act swiftly and ruthlessly’.115 On the following day, state secretary Weizsäcker, recorded that Hitler intended to deliver ‘the deathblow to what remains of Czechoslovakia’ in ‘about four weeks’.116

Thus Hitler was taking active steps to implement the policy of incorporating Czechoslovakia, mooted in November 1937, and finally decided on in May 1938. The unwelcome Munich Agreement had merely postponed the project; but, with the aid of the Slovaks, he had succeeded in using the winter to further destabilize Czechoslovakia (particularly since in Hitler’s view military operations in Central Europe during the winter were inadvisable). Encouraged by Hitler’s support, the Slovak government now demanded an extension of their independence from the Prague central government, thereby provoking a political crisis. On 9 March, the Prague government dismissed the Tiso cabinet in Pressburg, in order to prevent Slovakia from finally leaving Czechoslovakia, a move that was being strongly supported by Germany. On 10 March Goebbels noted: ‘Now we can completely resolve the issue that we only half resolved in October’.117 Around midday, he, Ribbentrop and Keitel were summoned to the Reich Chancellery and it was decided to march into Prague on 15 March. The German press were now instructed openly to support Slovakia’s claims to independence, and to launch a new campaign against the government in Prague. During the following days, the Propaganda Ministry exercised tight control over the reporting of the new crisis.118

In the late afternoon of 10 March, Hitler and Goebbels drafted an announcement to the effect that, before its dismissal, the Tiso government had appealed to the Reich for help. However, in the course of the night it became clear that Tiso was not yet willing to sign it.119 During the night of 11/12 March, a German delegation of around twenty people, including the Anschluss specialists, Seyss-Inquart, Bürckel, and Keppler, arrived in Pressburg, and presented what was virtually an ultimatum to the Slovak ministers present, demanding that they declare Slovakian independence. They, however, rejected it, whereupon Tiso was summoned to Berlin.120 Heroes’ Memorial Day was being celebrated in the capital on 12 March and the atmosphere already hinted at Hitler’s impending move against Czechoslovakia. During the official celebrations, Admiral Raeder declared, in Hitler’s presence that Germany was the ‘patron of all Germans both within and beyond our frontiers’.121 On the same day, Hitler ordered the armed forces to prepare for the occupation of Czechoslovakia on 15 March.122 Simultaneously, he decided to allow Hungary to occupy Carpatho-Ukraine, which he had refused them as recently as November.123 The government of this hitherto autonomous region had declared its independence on 13 March, placing itself under the protection of the Reich.124 However, from Hitler’s point of view, during its short period of existence since October, it had already fulfilled its function of contributing to the disintegration of Czechoslovakia; now it was more important to have the gratitude of Germany’s ally, Hungary, whose troops began occupying its tiny neighbour on 14 March. It was left to state secretary Weizsäcker to inform the government of Carpatho-Ukraine on 15 March that the Reich government ‘was regrettably not in a position to establish a protectorate’.125

Tiso arrived in Berlin on 13 March, where Hitler offered him ‘assistance’ in establishing an independent state. Tiso had a matter of ‘hours’ to make up his mind; if he did not accept, Hitler indicated that he would no longer oppose Hungary’s ambition to occupy Slovakia. However, Tiso refused to commit himself.126 Ribbentrop then worked on Tiso during a session lasting nearly six hours, finally presenting him with an ultimatum to declare his country’s independence the following day and, for his return journey to Pressburg, gave him the text of a telegram, appealing for help from the German government.127 Impressed by Tiso’s report on his Berlin meetings, on 14 March, the parliament in Pressburg declared the independence of Slovakia and elected Tiso prime minister; however, the telegram requesting help was only released on 15 March128 under German pressure.129 On 17 March, the new state formally recognized its dependence on the German Reich in a ‘treaty of protection’.130

The Czech president, Emil Hácha, and his foreign minister, Chvalkovský, arrived in Berlin on the evening of 14 March. Hitler forced them to wait for hours and then, during the night, and in the presence of, among others, Keitel, Göring, and Ribbentrop, subjected them to massive pressure, finally compelling them to capitulate.131 They had to sign a declaration, committing themselves to placing ‘the fate of the Czech people and country trustingly in the hands of the Führer of the German people’, who in turn promised ‘that he would place the Czech people under the protection of the German Reich and guarantee the autonomous development of its ethnic life in accordance with its particular character’.132 The German invasion of Czech territory began in the early morning. Hitler followed his troops, arriving that evening at Prague Castle in a convoy of vehicles.133 The following day he signed a decree establishing a ‘Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia’,134 placing the territories occupied by his troops under the Reich’s ‘protection’. The ‘autonomy’ granted to the Protectorate was to be supervised by a ‘Reich Protector’ residing in Prague, who was also responsible for confirming the members of the Protectorate’s government. Hitler appointed the former Foreign Minister, Neurath, as Reich Protector.

Hitler left Prague on the afternoon of 16 March, in order to return to Berlin via Brünn, Vienna, and Linz.135 On 19 March, the Party organized ‘spontaneous demonstrations’, as they were described in the Berlin press conference, throughout the Reich.136 In the capital Goebbels prepared another triumphal entry for Hitler. According to the Völkischer Beobachter, ‘never in the history of the world was a head of state paid such homage’. The boulevard, Unter den Linden, was transformed into a ‘canopy of light’ by means of anti-aircraft searchlights, above which there was a firework display.137

In fact, the new coup does not appear to have produced overwhelming enthusiasm among the German population. While, on the one hand, there was certainly admiration for the renewed proof of Hitler’s abilities as a statesman, there was, on the other, also surprise, criticism, and the fear of war.138 Even Hitler’s Luftwaffe adjutant, Below, wondered: ‘Was it necessary?’ In doing so, he hit the nail on the head,139 for, unlike their ‘Führer’, the majority of Germans did not consider the occupation of Prague, Bohemia, and Moravia as the fulfilment of longstanding plans for the future of a Greater Germany.

Hitler’s decision to tear up the Munich Agreement and occupy the ‘remainder of Czechoslovakia’ prompted the British and French governments to undertake a fundamental revision of their attitude to Hitler’s dictatorship. For, with the incorporation of non-German territories, it had become apparent that Hitler’s justification for his previous policies, namely that, acting on the principle of national self-determination, he was only bringing all Germans together in a single Reich, was simply a pretext for a brutal policy of expansion, while unscrupulously ignoring the rights of other nations. London and Paris now realized that the line followed hitherto of trying to appease Hitler by making more and more concessions had been a miscalculation. Dealing with Hitler clearly required another language.140 He, however, did not take seriously the warning voices and the formal protests from Paris and London; both countries recalled their ambassadors for consultations.141 Instead, he declared himself convinced that the British prime minister was simply pretending to ‘take action’.142

The fact that Hitler only informed Mussolini subsequently about the occupation of Prague was also not conducive to strengthening the relationship of trust between the ‘Axis power’, Italy, and its ally north of the Alps, and very probably contributed to Mussolini’s decision not to coordinate with Hitler the next steps in his policy of expansion.

The annexation of Memel

Completely unimpressed by these protests, after his return from Prague Hitler immediately embarked on his next diplomatic ‘coup’, the incorporation of Memel into the Reich.143 This territory, whose approximately 140,000 inhabitants were largely of German extraction, had been separated from Germany by the Versailles Treaty and had initially been under French administration; in 1923 it was occupied by Lithuania and, from 1924 onwards, had been administered by Lithuania as an autonomous territory on the basis of an international convention. In his directive of 21 October 1938 Hitler had already demanded the ‘capture of Memelland’, when the ‘political situation’ allowed it.144

On 1 November, under German pressure, the Lithuanian government had lifted martial law, which had been operating since 1926. A Memel German electoral list, dominated by Nazis, was then drawn up and, in an election on 11 December, was able to establish itself as the dominant political force, effectively coordinating the country with Nazi Germany and demanding its return to the Reich.145 In December, Hitler, accompanied by Ribbentrop, received Ernst Neumann, a leading representative of the Memel Germans and told him that Memel would be incorporated into Germany in March or April the following year; until then, he must maintain discipline among the Memel Germans.146

On 20 March 1939, Ribbentrop gave the Lithuanian foreign minister, Joseph Urbsys, who was visiting Berlin, an ultimatum to give up the territory. Under pressure, Urbsys secured the agreement of the Lithuanian cabinet in Kovno and, on 22 March, signed the transfer agreement in Berlin.147 The following morning, German troops moved into the territory without meeting resistance. Hitler, who had boarded the cruiser ‘Deutschland’ in Swinemünde the previous evening, sailed up the Lithuanian coast with an impressive fleet. Around noon he then switched to a torpedo boat, landing in Memel harbour, which had previously been secured by a unit of marines. In Memel he greeted the Memel Germans with a brief speech as new members of the ‘Greater German Reich’ and then signed the transfer treaty aboard the ‘Deutschland’.148

On the evening of 24 March, now back in Berlin, and during a joint visit to the Wintergarten variety show, Hitler gave Goebbels an insight into his thinking on foreign policy: ‘The Führer is contemplating a solution to the Danzig question. He will try again with Poland, using a certain amount of pressure, and is hoping it will respond. But we shall have to bite the bullet and guarantee Poland’s borders.’149