A Mammoth Problem

TODAY, GEOLOGISTS KNOW THAT more than 99 percent of all animal species that have ever lived are extinct. You don’t have to know any geology to know that trilobites, dinosaurs, and saber-toothed tigers no longer live among us (unless you count birds as modern dinosaurs). Given this, it makes no sense to argue that Noah’s Flood explains the world’s fossils. If that were the case, it would mean the Flood not only caused extinctions but killed off almost all the world’s then living species—the very thing that Noah supposedly built his ark to prevent in the first place.

But in the opening days of the eighteenth century, naturalists and theologians alike were confident that extinctions had no place in God’s plan. Almost everyone assumed that living examples of fossils would eventually turn up as more of the world was explored. Vigorous arguments continued to rage over how God triggered Noah’s Flood, but after Steno, Burnet, and Woodward, natural philosophers increasingly interpreted internment of once-living creatures in rocks as compelling evidence of a divine disaster. After all, there was no way to know how old fossils were, no way to date when they had lived—or had died. Wasn’t the simplest answer that they had died all at once?

If the only idea you have to explain rocks and topography is a big flood, then you will naturally tend to interpret the evidence you find in terms of a big flood for as long as you can. Even scientists today are not immune to interpreting evidence, at least initially, through the lens of prevailing ideas and their preconceived notions. Centuries ago, when natural philosophers learned of fossils near the crest of the Andes, they concluded that the biblical flood parked the bones of sea creatures within South America’s highest mountains.

A problematic detail, however, muddied the waters—some fossils did not correspond to any known living species. One of the most striking fossils common in the layered (sedimentary) rocks of England were ammonites, snail-like marine animals with spiral shells characterized by distinctively crenulated partitions that created internal chambers. There was a dizzying array of different species and types of fossil ammonites, ranging in size from inches to several feet across. They were found throughout certain rock formations across southern England and were literally falling out of the cliffs to litter beaches along the English Channel. Yet nothing like them had ever been found alive anywhere in the world. Their closest living relative seemed to be pearly nautilus, an exotic chambered shell with simpler, noncrenulated partitions from the East Indies. Most natural philosophers shrugged off this problem, confident that someday someone would dredge a living ammonite up from the sea. They thought that only a flood of awesome power, the biblical flood, could have entombed on land creatures thought to live in the very deepest part of the ocean.

The views of diluvialists—those who invoked Noah’s Flood to explain what they found in the rocks—dominated geological thinking until natural philosophers demonstrated that fossils were extinct and that Earth had a much longer and more complicated history.

A leading voice of the diluvialists was Johann Scheuchzer, one of continental Europe’s great fossil enthusiasts. After completing a doctorate in medicine at Utrecht in 1694, he returned home to Zurich, where he eventually became a professor of mathematics. Insatiably curious about the natural world, Scheuchzer served as the secretary of a weekly club that held lively discussions on controversial topics such as whether the devil could physically seduce a woman and whether mountains were created along with the world or formed during Noah’s Flood.

Scheuchzer’s passionate interest in Swiss natural history led to extensive walking tours through the Alps. Accompanied by his students, he made geological observations and was the first to measure—by carrying a barometer up a mountainside—how air pressure changed with altitude. Fossils especially fascinated him. He had been taught they were mineral oddities whose origin could be explained by physics and chemistry.

When Scheuchzer read Woodward’s essay, he realized that fossils really were ancient creatures. Right under his nose, entombed in his own rock collection, were the remains of snails, seashells, fishes, and plants. This revelation prompted his own landmark work in 1708, The Fishes’ Complaint and Vindication, in which Scheuchzer lampooned the still popular idea that fossils were inorganic objects that just happened to resemble real creatures. He shaped his narrative from the point of view of a fossil fish who complained in formal Latin about not being recognized as an innocent victim of the flood sent to destroy mankind.

“We, the swimmers, voiceless though we are, herewith lay our claim before the throne of Truth. We would reclaim what is rightly ours. . . . Our claim is for the glory springing from the death of our ancestors . . . carried on the waves before the Flood. . . . We bear irrefutable witness to the universal inundation.”1

Scheuchzer’s fossil narrator righteously demanded the dignity of being recognized as having suffered alongside mankind during the Flood. Speaking for innocent marine creatures that died when receding floodwaters stranded them on dry land, it added insult to injury to deny that their own bones testified to their existence. The fossilized spokesman introduced detailed illustrations of marine fossils that any fisherman would recognize as the remains of familiar animals.

The year after his fossil fishes spoke up, Scheuchzer published Herbarium of the Deluge, a collection of botanical prints illustrating plant life purportedly fossilized as a result of the Flood. This collection of striking images showed exotic plants set in stone, offering a window into a world before our own. That ferns and tropical plants had been growing in Europe drew open the curtain of time to reveal a radically different world.

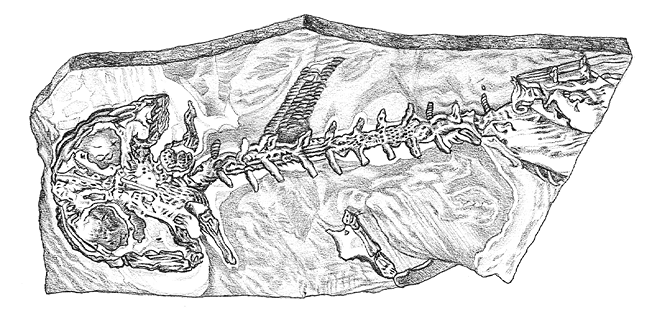

Seduced by what he saw as fossilized postcards of life before the Flood, Scheuchzer kept looking for more flood victims. The limestone quarry at Oenigen, in the Alps near the west end of Lake Constance, gave him access to fossil fish, bullfrogs, snakes, and even turtles. He saw these fossils, now known to date from the Miocene epoch (ten to twenty million years ago), as relics of Noah’s Flood deposited along with the rest of the world’s sedimentary rocks. Then in 1725 stone workers at the quarry unearthed part of an unusually large skeleton and shipped it off to Scheuchzer, who promptly interpreted it as another flood victim. What better testimony to the veracity of the biblical flood than the bones of a drowned sinner?

Naming this unlucky fellow Homo diluvii testis (man who testifies to the Flood), Scheuchzer sent off descriptions of his incredible find to British, French, and German journals and published a short book that shared the fossil’s name. Scheuchzer’s discovery of a human witness to the Flood not only showed that a world of sinners drowned but that they were giants, just like the Bible implied when it said “there were giants in the earth in those days” (Genesis 6:4). Scheuchzer had a ready answer for the dearth of human remains in the rocks laid down by the Flood. The bones of innocent animals were to remind us of their sacrifice, whereas the rarity of human remains confirmed that sinners deserved condemnation to eternal oblivion.

Convinced he had found proof of Noah’s Flood, Scheuchzer spent his last years compiling his Sacred Physics, in which he sought to harmonize natural history with scriptural truths. He proposed that the fountains of the deep had burst forth when the hand of God literally reached out and applied the brakes to Earth’s rotation, stopping the world dead in its tracks, splitting continents apart and spilling out subterranean seas to produce the biblical flood.

That idea didn’t catch on, but Scheuchzer’s human flood victim was a sensation. A museum in Haarlem acquired Homo diluvii to show it off to the faithful. Although natural philosophers decided within a few decades that it probably was just a big fish, it remained a popular attraction until 1812, when the prominent French anatomist Georges Cuvier, whom we’ll meet shortly, authoritatively declared it otherwise. Ironically for a talented naturalist, Scheuchzer’s faith that the geologic record told the story of Noah’s Flood led him to the colossal blunder he is still lampooned for today. As Cuvier pointed out, Scheuchzer’s flood victim was a giant amphibian.

Homo diluvii, the fossil Johann Scheuchzer interpreted as a victim of Noah’s Flood (by Alan Witschonke based on plate XLIX of Scheuchzer’s Sacred Physics (1731)).

These were not the only strange bones attributed to Noah’s Flood. All across Europe large fossils were publicly displayed as the remains of the giants mentioned in scripture. Scheuchzer didn’t get it all wrong, because he pointed out that the enormous stone teeth of those purported to have drowned in the Flood actually belonged to something more like an elephant than a person.

The expansion of European power and influence in the eighteenth century led to the discovery of giant bones in Siberia and North America. In 1692, Peter the Great’s envoy to China, Ysbrand Ides, found frozen tusks and hairy elephant carcasses exposed in a Siberian riverbank. His report claimed these behemoths lived before the biblical flood, their frozen hulks preserved by a frigid post-Flood climate.

Further expeditions returned to St. Petersburg with the partial remains of huge creatures that the indigenous Siberians called “mammut,” a name European tongues promptly changed to mammoth. Within a few decades, such discoveries convinced natural historians that there was an abundance of fossil elephants in Siberia, a place too cold for African animals to survive today. With the closest living elephants located in India, natural historians tended to interpret the Siberian bones as those of creatures swept north from Asia by a great flood, in much the way remains of African elephants were thought to have made it to Europe.

Similar finds in North America were also attributed to Noah’s Flood. Large bones found along the banks of the Hudson River in upstate New York were thought to be those of an antediluvian giant. Discovered eroding from a hillside in 1705 near Albany, a six-inch-tall, two-and-a-quarter-pound tooth and a seventeen-foot-long thighbone convinced Cotton Mather, of Salem witch trial fame, that giants really did drown in the Flood. Dug out from the base of the hill, the great thighbone crumbled away when exposed to the air. Mather was convinced that the more durable four-pronged tooth looked like a human molar, only much bigger. All who saw it thought that this was a victim of Noah’s Flood. Based on the size of such bones, one authority estimated that Adam was well over a hundred feet tall. Mather’s giant bone, however, was probably a mammoth bone.

Mather was enthralled with his fossil finds, and in November 1712, he wrote the first of a series of letters to the Royal Society in London to bring to the attention of scholars these New World curiosities from the time of the Flood. He also reported accounts of giant bones discovered in South America, convinced that they, too, were proof of Noah’s Flood.

Below the Strata of Earth, which the Flood left on the Surface of it, in the other Hemisphere, such Enormous Bones have been found, as all Skill in Anatomy, must pronounce to belong unto Humane Bodies, and could belong to none but GIANTS. . . . The Giants that once Groaned under the waters, are now found under the Earth, and their Dead Bones are Lively Proofs of the Mosaic History.2

The flood that buried giants appeared universal in Mather’s mind and fit in well with his belief that Moses described Noah’s Flood as a global event. In 1721, Mather wrote The Christian Philosopher, the first systematic book on science published in America. Invoking fossils as direct evidence of a global flood, it was dedicated to the argument that reason supported faith.

Not everyone was convinced that giant bones were the bones of giants. Around 1725, English botanist Mark Catesby visited Stono, a large plantation near Charleston, South Carolina, to examine gigantic teeth that slaves had unearthed from a swamp. While the plantation owners thought that the colossal molars were the remains of a giant that drowned in the Flood, the native Africans who had found them swore that they were dead ringers for elephant teeth. Catesby scandalously shocked his hosts by agreeing with their slaves. Unlike the plantation owners, he had seen elephant teeth on display in London.

Catesby got closer than Mather to deducing the true origin of giant bones, but it was not until the next decade that the bones were pegged to mammoths. Exploration of the vast, unexplored wilderness west of the Appalachians proved to be key. In 1739, a French military expedition traveling from Niagara to the Ohio River discovered enormous bones at a salt lick near the river. Recognizing the value of this cache of fossils, the commander of the expedition sent a fossil tusk, a giant femur (thighbone), and several huge teeth down the Mississippi and on to Paris. The site became famous as Big Bone Lick. While some natural philosophers believed that these mammoths were a new species larger than modern elephants, others thought that the difference in size between modern and fossil bones was no greater than the degree of variation in size among modern elephants.

Thomas Jefferson, for one, was convinced that North American mammoths were the same species as Siberian mammoths, distant hairy cousins of tropical elephants adapted to life in cold climates. Jefferson had an intense interest in the natural world and plants and animals. The prospect of living behemoths among the fauna of the American wilderness thrilled him. As governor of Virginia, he was familiar with the fossil discoveries at Big Bone Lick, which then lay within the expanded borders of his state. In 1781 Jefferson published his Notes on the State of Virginia, the only full-length book he wrote, in which he described mammoths as larger than an elephant and told how Native Americans considered the giant bones at Big Bone Lick to be those of the “Big Buffalo,” the largest of animals. He related native stories that told of how the giant teeth from Big Bone Lick belonged to an enormous carnivore that still roamed America’s unexplored northern wilderness.

Jefferson collected examples of the richness, vigor, and brute size of American wildlife, even displaying a taxidermied bear inside the White House, to counter French claims that European animals were superior to American fauna. What could better make the case for the superiority of American animals than an elephant-sized predator? It would be a powerful symbol of his new nation, embodying the independence and strength of the American character. Trappers and explorers were still finding new, exotic animals west of the Appalachians. Might not someone find a living mammoth? This was the same argument European savants used to rationalize why no one had ever seen a living ammonite. But, unlike ammonites, mammoths could not be hiding in the deep sea.

Across the pond, scholars were starting to doubt that mammoths were still alive and well. Near the close of the century, in 1796, Georges Cuvier, a professor of natural history at the College de France and the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, compared bones of mammoth carcasses to those of African and Indian elephants. Mammoths matched neither living species. But if Noah saved all the animals, how could these fossils represent extinct animals? Was this possibly evidence of animals that lived and died long before the Flood and that inhabited a world much older than the one laid out in Genesis?

A lifelong churchgoer, Cuvier was born into a Lutheran family in the French-speaking German Duchy of Württemburg. By the time of the French Revolution, he had built a reputation as an expert in animal anatomy, studying marine organisms while working as a tutor for a family of nobles in Normandy. When France annexed his hometown, he moved to Paris, where he was appointed understudy to an aging professor. He had a unique talent for understanding the relation between invertebrate form and function, and rapidly rose to prominence in scientific circles. Cuvier also served as the vice president of the Bible Society of Paris. At the natural history museum, he had the opportunity to see collections of fossils from all over the world.

When the revolutionary armies of France swept through what is now Belgium, an official team of trained specialists, including a naturalist, accompanied them to plunder useful or valuable objects. Most of the team focused on acquiring the best crop varieties and agricultural machinery. The naturalist had an eye for extraordinary fossils and returned to Paris with loot fit for a king.

As a hundred and fifty crates of specimens from France’s new conquests to the east arrived at the museum in Paris, so, too, did Cuvier. It was to be a turning point in his thinking and career. He found two elephant skulls among the samples that were unpacked in the auditorium, one from southern Africa and the other from Ceylon (Sri Lanka), off the southern coast of India. Cuvier carefully measured and analyzed these skulls alongside those of Siberian mammoths and found that they were from distinctly different species. The conclusion was clear—the mammoth skulls resembled no living species.

He also compared the teeth of elephants and mammoths with those from Big Bone Lick. The grinding surface of the teeth of one of the American specimens was covered with unusual knobs that resembled small breasts. This was a different species than the Siberian mammoths, which had raised ridges on their teeth. He named the peculiar American specimen “mastodonte,” breast-tooth.3

Cuvier concluded that there were three kinds of elephants. There were the modern African and Asian species, the Siberian mammoth (which also had lived in North America), and the mastodon, which was only found in North America. Although they were all herbivores, mammoths ate grass and mastodons ate woody shrubs and trees. The uncomfortable fact that both were extinct opened the door to seeing plants and animals as organic beings subject to change.

How many other species were extinct? When did they die off, and what was the world like when they lived? Cuvier put his expertise in comparative anatomy to work by analyzing fossils to reconstruct the inhabitants of vanished worlds. He found that whole faunas preserved in stone were distinct from living species. His findings convinced him that ancient worlds were radically different from the one he knew. The world had a complicated and dynamic history. Species came and went through time.

Cuvier thought that the story told by rocks and fossils roughly paralleled a nonliteral reading of Genesis. He also thought that the story of Noah’s Flood was the story of some type of recent global catastrophe, which had wiped out large mammals known only through their fossils, like mammoths. Cuvier maintained that the legends of the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Jews all pointed to a grand disaster immediately prior to the dawn of human history.

Cuvier sought to marshal observable facts to trace the history of the world and to understand the sequence of grand disturbances, or revolutions that had punctuated earth history. It seemed that life had turned over every now and then throughout geologic time. The story Cuvier read was one that began with initial life-forms and transformed into a world of ammonites and sea life. Then, a whole succession of worlds with novel terrestrial faunas arrived, with people arriving in the most recent, modern world.

Offered the chance to accompany Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt, Cuvier chose to stay close to the collection of the museum. He preferred to have specimens come to him and issued an appeal for collectors to send fossils, drawings, or descriptions for him to assess. In return, he offered to authoritatively identify the bones, a skill that few others in his day possessed. Cuvier’s masterful ability to relate the structure of organisms to their biological function netted him a role as a scientific referee on issues related to vertebrate anatomy. Today, he is known as the founder of vertebrate paleontology.

In the first public summary of his research, Cuvier treated fossils as if they were all the same age. The bones of fossil elephants (mammoths) were evidence of a previous world destroyed by some kind of catastrophe. Later, as he came to realize that different geological formations held distinctive fossils, he recognized that the fossils in the older beds were progressively different from the modern fauna.

As he continued to amass specimens, Cuvier increasingly recognized patterns in the organization of life through time. Ammonites were found exclusively in the lower and therefore older formations, mammoths were found in the highest and most recent formations of surficial debris. Human bones were not found as fossils. If fossils truly represented extinct plants and animals, and not just species hiding out in the deep sea or in unexplored wilderness, then Earth had a distinct history in which life approached the form of the present fauna through the turnover of species unlike any known today. Cuvier’s skills, intellect, and intuition combined to lead the way forward in piecing together earth history. His advances rivaled those of any other scholar up until that time.

Cuvier speculated that extinctions happened during violent geological revolutions, sudden disasters for which he invoked the well-preserved bodies of mammoths as evidence: “In the northern regions it has left the carcases of some large quadrupeds which the ice had arrested, and which are preserved even to the present day with their skin, their hair, and their flesh.”4 In Cuvier’s view, developed from the great number of fossils he studied, a not quite six-thousand-year-old Earth was simply inadequate to accommodate the diversity of fossil life. Certainly, one great flood was not enough to explain earth history. “Life, therefore, has been often disturbed on this earth by terrible events—calamities which, at their commencement, have perhaps moved and overturned to a great depth the entire outer crust of the globe.”5

We now know of at least five mass extinctions in the geological past, and biologists say another one is under way as we wipe species off the planet 100 to 1,000 times faster than nature did before we started helping out. Since the evolution of life on land, several events have killed off over half of all animal species. Every school kid learns that dinosaurs died off and mammals began rising 65 million years ago during the great Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event. The less well-known, but far deadlier, Permian-Triassic extinction event 251 million years ago killed off almost all of the animal species on Earth, ending the age of trilobites and setting up the rise of dinosaurs. More recently, the last glaciation of the Quaternary Period (the so-called ice age of the past several million years) saw the demise of megafauna, like mammoths, and ushered in a modern world increasingly dominated by people. When viewed through the geologic record millions of years from now, the modern extinction event we are living through may well look similar to past grand catastrophes that ended ancient worlds.

After Cuvier, the drive to find evidence for Noah’s Flood in the rocks was well and truly dead, although modern creationists would later resurrect the idea. While natural philosophers were long wedded to the idea that fossils confirmed the biblical account of a great flood, once they established the reality of extinctions in the geologic record, it showed that Noah’s Flood could not have deposited all the world’s fossils. They then shifted to looking for the signature of the Flood in the overlying unconsolidated deposits of gravel and boulders. This new view helped natural philosophers and theologians alike accept a pivotal reinterpretation of the Bible, one that made room for a new concept of time—time enough that fossils need not have all died, or lived, at the same time. Thanks to a Scottish farmer, today we know this idea as geologic time.