Figure 1.1 Susette Kelo’s famous “little pink house.” (Credit: Photo by Isaac Reese, 2004. Courtesy of Institute for Justice.)

The case that led to one of the most controversial decisions in mod

ern Supreme Court history arose from unlikely origins in the little-known Fort Trumbull neighborhood of New London, Connecticut. It began with a small group of property owners who decided to resist the condemnation of their homes and other properties as part of a development plan intended to promote economic growth. Under normal circumstances, their case might never have gotten to court at all, as those targeted by eminent domain might not have had the time, energy, and resources needed to fight a prolonged legal battle. If it nonetheless had resulted in litigation, it could easily have ended at the state level in a decision that would have attracted little attention beyond Connecticut.

That the case became nationally famous was due to the dogged perseverance of the property owners whose land was threatened, the intervention of a major public interest law firm, and what many considered to be the surprising willingness of the Supreme Court to reopen an issue that expert opinion believed to be long settled: the power of the government to condemn private property for purposes of transferring it to other private owners. The seemingly local conflict that began in Fort Trumbull would ultimately trouble the conscience of an entire nation.

The history of the Fort Trumbull takings has already been effectively recounted in an excellent book by journalist Jeff Benedict.1 But Benedict’s main interest was in telling the story on the ground rather than exploring the constitutional and policy questions raised by the case. This chapter builds on his work, emphasizing those points that are most relevant to the broader issues that were eventually implicated by the Supreme Court’s decision.

Bulldozing a Path to Prosperity

The Fort Trumbull peninsula of New London, Connecticut had once been a moderately prosperous area. But the area’s economy was heavily dependent on the Naval Undersea Warfare Center located on the peninsula. It began to fall on relatively hard times in the 1990s around the time the center was closed as a result of post-Cold War defense cuts in 1995.2 Both area residents and city officials hoped to revitalize the region.

Despite the difficult economic conditions, some residents—including those who later played a major role in the Kelo case—believed that Fort Trumbull could recover and that it remained an attractive place to live and do business. Richard Beyer, who had grown up in New London, bought two small properties in Fort Trumbull in 1994, in which he and a business partner then invested a substantial amount of money to refurbish them for use as rental units.3 Although he acknowledges that economic conditions were difficult, Beyer believed that “without question,” the area had potential, so much, in his view, that “[y]ou really can’t lose” by investing there.4 Bill Von Winkle, another future Kelo plaintiff, had a similar story. He too had grown up in the area, and purchased several properties to refurbish as rental units in the 1990s, and also lived in one of them for a time.5 All told, he had owned property in the area for twenty-four years, and had a total of twelve apartment rental units, a commercial building, and a restaurant.6 At the time the Kelo condemnations began, he had recently spent some $300,000 on renovations.7

Susette Kelo, the EMT who became nationally famous because her name was listed first among the plaintiffs in the Supreme Court case, bought a home in Fort Trumbull in 1997.8 Although the house needed work, she fell in love with its impressive “water view” and what she called its “pizzazz.”9 This was the home that later became famous as the “little pink house” that became an iconic image of the struggle over the Fort Trumbull condemnations.10 Byron Athenian, owner of an autobody shop, had purchased a house in the same area in the late 1980s, where he lived with his family, including three children.11 He too liked the area and did not wish to move.

Others had lived in Fort Trumbull for many years and had deep attachments to the community. Pasquale and Margarita Cristofaro, an elderly Italian American couple, had purchased a house in Fort Trumbull in 1972, after their previous residence had been condemned as part of

Figure 1.1 Susette Kelo’s famous “little pink house.” (Credit: Photo by Isaac Reese, 2004. Courtesy of Institute for Justice.)

Figure 1.2 The Cristofaro house. (Credit: Photo by Isaac Reese, 2004. Courtesy of Institute for Justice.)

an urban renewal taking.12 The Cristofaros, whose son Michael spoke for them in the Kelo litigation, were dead set against losing yet another house to eminent domain.13 By the late 1990s, the elder Cristofaros had moved to a different location, though they continued to own the house, which was now occupied by Michael’s elder brother and his family. He had recently retired after twenty-three years of service in the U.S. Air Force, and, according to his brother, “hope[d] that this was his last move and [he] would finally be able to settle down.”14

Matthew Dery came from a family that had owned property in Fort Trumbull since 1890.15 As of the late 1990s, they owned four houses in the area, one in which Dery lived with his family; two rental units; and one where Dery’s elderly parents, Charles and Wilhelmina, lived.16 Now in her eighties, Wilhelmina Dery had been born in that house in 1918, had never lived elsewhere, and ardently wished to continue living there for as many years as she had left.17

While the future Kelo plaintiffs liked living in the Fort Trumbull area and believed it was a good community, they also recognized that it had significant economic problems in the wake of the closure of the Naval Undersea Warfare Center. Richard Beyer, for example, told me that there was “a lot of negativity” in the air about the local economy in the 1990s and that “nothing was being done” to improve it.18 In addition to the area’s general economic doldrums, a nearby old city-owned sewage plant periodically emitted a terrible odor that annoyed many residents.19

New London city officials also recognized the economic difficulties the area faced. They hoped to revitalize it, as well as the city in general. In 1997, they reestablished the New London Development Corporation, which the Supreme Court would later describe as a “private nonprofit entity established . . . to assist the City in planning economic develop-ment.”20 The NLDC would ultimately produce the plan that resulted in the Fort Trumbull condemnations.

The NLDC was reestablished after a period of dormancy, under the leadership of a new president, Claire Gaudiani, an academic and president of Connecticut College with a long history of involvement in philanthropic and social justice causes.21 The NLDC’s resuscitation occurred in large part at the behest of the administration of Republican Connecticut Governor John Rowland. The Republican administration hoped to increase its political support by promoting economic development in overwhelmingly Democratic New London, but wanted to do it by working through an agency that was not controlled by the City’s Democratic elected government, which was generally hostile to the governor.22 The administration recruited Gaudiani to become the new president of the NLDC because of her prestige as the president of the area’s most prominent academic institution, her leadership skills, and her interest in community development.23

Although this was not the reason for her selection to lead the NLDC, Gaudiani was also the wife of Dr. David Burnett, a high-ranking employee of Pfizer, Inc., then the world’s largest pharmaceutical producer.24 Her knowledge of Pfizer led Gaudiani to recruit Pfizer executive George Milne to join the NLDC board, in part because she hoped that having a prominent corporate leader as a member would help attract investment to New London.25 But Gaudiani also hoped it would facilitate bringing Pfizer to the area, since she knew that the firm was in search of a location where it could build additional office space for a new headquarters, and New London fit the firm’s needs.26

In the fall of 1997, Gaudiani and Milne initiated discussions with Pfizer urging them to move to a former mill site location that had become available in New London.27 Pfizer began to show interest, and the firm and the NLDC engaged in further discussions with state officials, led by Peter Ellef, director of the state’s Department of Economic Cooperation and Development, and an important adviser to Governor Rowland.28 As a condition of moving to the New London site, Pfizer insisted that the city and state acquire ninety acres of property in Fort Trumbull—including the former naval research facility and some sixty acres of other property—in order to turn them into upscale housing, office, space, a conference center, a five-star hotel, and other facilities that would be useful to the corporation and its employees who would work in the area.29 While Pfizer would not be the new owner of the properties in question, it expected to benefit from their redevelopment.

Throughout the course of the Kelo litigation, Pfizer and NLDC representatives insisted that the firm was not involved in initiating the effort to condemn and redevelop the Fort Trumbull properties and that it had not made such redevelopment a condition of its decision to open up a new headquarters facility in New London.30 But evidence introduced at the trial, as well as additional documentation uncovered by an investigative reporter for the New London newspaper The Day in late 2005, several months after the Supreme Court’s Kelo decision was issued, shows that Pfizer “ha[d] been intimately involved in the project since its inception” and that the NLDC development plan and associated condemnations were “a condition of Pfizer’s move” to New London.31

Documents obtained by The Day through state Freedom of Information Act requests show that the NLDC condemnations were undertaken in large part as a result of extensive Pfizer lobbying of state and local officials.32 Pfizer representatives did indeed demand the redevelopment plan and its associated takings as a quid pro quo for its agreement to build a new headquarters in New London.33 In the fall of 1997, Pfizer had had a consulting firm prepare a design sketch for the proposed redevelopment of the Fort Trumbull area, which included proposals for the construction of a “high end residential district” and other facilities that would be of use to the firm and its employees.34 These ideas became the basis of an eventual agreement between Pfizer and state officials under which the firm agreed to establish a new headquarters in New London in exchange for some $118 million in state government subsidies and an additional $73 million allocated for the clearing and redevelopment of the Fort Trumbull area.35 State officials claimed that the combination of Pfizer’s move and the redevelopment project would generate some two thousand new jobs in New London.36 While much evidence of Pfizer’s involvement in the taking was already known before the 2005 revelations, and introduced in court, the 1997 design and its role in the planning process was not.37

Most of the specific facilities that Pfizer wanted built could probably have been constructed without eliminating all the houses in the area.38 But NLDC leaders and Pfizer officials also believed that it was essential to wipe out all the existing buildings for aesthetic reasons. David Burnett, a high-ranking Pfizer employee and husband of Claire Gaudiani, told a reporter that the houses had to be destroyed because “Pfizer wants a nice place to operate,” and “we don’t want to be surrounded by tenements.”39 Gaudiani herself stated that the houses had to be knocked down because otherwise they would have looked “ugly and dumb.”40 In 2005, NLDC lawyer Ed O’Connell told the New York Times that the homes owned by the preexisting owners had to be torn down in order to make way for “housing at the upper end, for people like the Pfizer employees . . . They are the professionals, they are the ones with the expertise and the leadership qualities to remake the city—the young urban professionals who will invest in New London.”41

Even before these revelations, the resisting New London property owners and other critics of the project believed that it was undertaken for the purpose of benefiting Pfizer. Richard Beyer, for example, thought the whole project was an “organized land grab” undertaken for the firm’s benefit.42 Bill Von Winkle similarly contends that the project was “Pfizer, 100% Pfizer, wanting us out of our homes.”43 Journalist Jeff Benedict, author of by far the most detailed account of the development of the Fort Trumbull project, concluded that Gaudiani, Milne, and other NLDC leaders genuinely believed that the plan would benefit the people of the city.44

It is extremely difficult to divine their subjective motivations with any certainty. My own view, however, is closer to Benedict’s than Beyer’s. Having interviewed Gaudiani, I am convinced that she genuinely believed that she was acting for the public good and was not simply trying to advance the private interests of Pfizer.45

But it is nonetheless problematic that a city redevelopment plan that was closely based on Pfizer’s demands was produced by an agency headed by the wife of a high-ranking Pfizer employee and including a Pfizer executive on its board. At the very least, this created a potential conflict of interest. And even if Gaudiani and Milne genuinely believed they were acting in the public good, it is hard not to wonder whether their perception of where the public good lies was affected by their respective connections to Pfizer. People have an understandable tendency to believe that their own interests coincide with the public good,46 and the NLDC leadership may not have been immune to this common pattern.

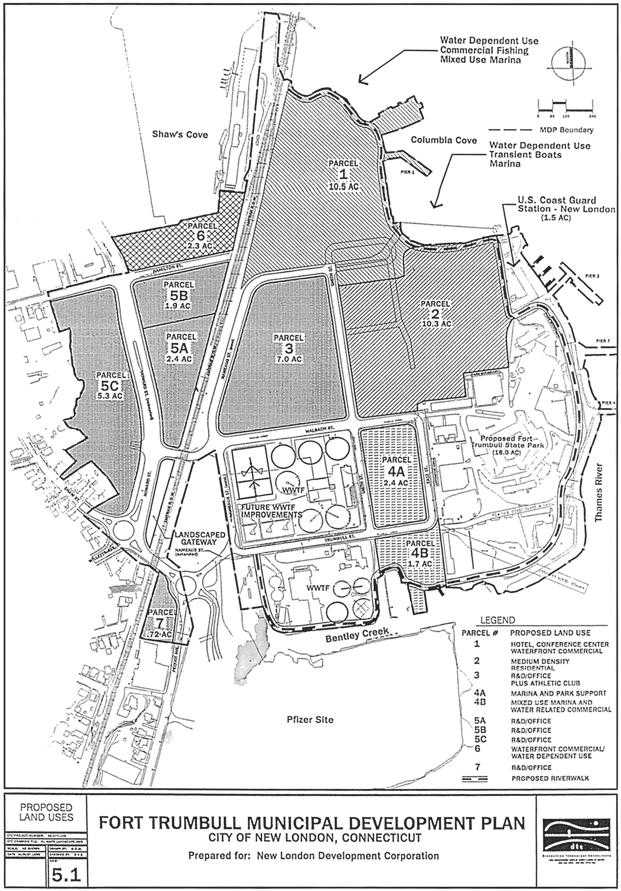

Figure 1.3 1999 NLDC Municipal Development Plan map of Fort Trumbull, with proposed future uses. The Athenian, Beyer, and Cristofaro properties were on Parcel 3. The Dery, Guretsky, Kelo, and Von Winkle properties were on Parcel 4A. (Source: Kelo v. City of New London, No. 104-08, U.S. Supreme Court, Joint Appendix, Vol. I, p. 212.)

In February 1998, Pfizer officially announced its plan to open up the new headquarters in New London. There was great optimism about the potential impact on the community. When the facility officially broke ground in September 1998, Connecticut Governor John Rowland, whose administration had provided crucial support for the venture, called it “without a doubt the most exciting partnership we have seen in the State of Connecticut,” one that “will change the landscape of this community for the next 100 years.”47 Claire Gaudiani hailed the event as “the beginning of a whole new day for New London,” and George Milne promised that “[t]his is done with the commitment that if we turn this shovel, there’ll be no turning back.”48

The NLDC meanwhile, prepared a municipal development plan that outlined an ambitious proposal to rebuild Fort Trumbull, while meeting Pfizer’s requirements.49 The plan called for the leveling of all the structures in the entire development area and their replacement with a variety of facilities, including a marina, a park, a hotel, office space, and upscale housing.50 Despite former Mayor Lloyd Beachy’s opposition, the New London City Council ultimately approved the plan in a 6-1 vote in January 2000, and authorized the NLDC to use eminent domain to acquire any property in the area whose owners were unwilling to sell.51

Condemnation

Even before the city council officially gave it the power to use eminent domain, NLDC representatives began to work to persuade Fort Trumbull property owners to sell their land, often threatening to use eminent domain against them if they refused.52 Defenders of the New London condemnations argue that most Fort Trumbull residents agreed to sell their property voluntarily. NLDC Director John Brooks claims that “the vast majority of the properties were acquired in a friendly way.”53 It is indeed true that only seven of the ninety property owners in Fort Trumbull ultimately chose to contest the NLDC’s efforts to acquire their land.54 But the voluntariness of the transactions by which the others gave up their property is at the very least extremely questionable.

The threat of eminent domain often played a key role in inducing “voluntary” sales. As New London’s lawyer Wesley Horton noted in oral argument at the Supreme Court, “[t]he large share of [the Fort Trumbull property acquisitions] was [voluntary], but of course, that’s because there

is always in the background the possibility of being able to condemn . . . that obviously facilitates a lot of voluntary sales.”55 When the possibility of using eminent domain to displace Fort Trumbull residents was first publicly discussed in early 1998, numerous residents wrote letters to the state Department of Economic and Community Development indicating that, though they might support redevelopment, they had a strong preference for remaining in their homes. As The Day reported in January 1999, “among the letters were comments such as ‘I am a senior citizen who has lived here 27 years and am not about to move’; ‘I am not interested in selling my home’; and ‘I’ve lived here since 1958 and I do not want to move.’ ”56

Interviews with the Kelo plaintiffs and other Fort Trumbull property owners confirm that the NLDC used the threat of eminent domain to persuade them to sell “voluntarily.”57 One owner who ultimately agreed to a sale, told me that NLDC representatives had informed her and her husband that “that they could use eminent domain if we did not agree to sell.”58

The coercion involved in acquiring the “voluntarily” sold properties was not limited to the threat of eminent domain. The Kelo plaintiffs and other property owners who were reluctant to sell were also subjected to other forms of pressure.

In late 2000, Bill Von Winkle was sent a letter by the NLDC claiming that it now owned his property and that his tenants’ rent payments should be turned over to the NLDC. A few days later, NLDC representatives entered one of his buildings, forced the tenants to leave, and padlocked the doors in order to prevent them from returning, despite the cold winter weather.59 Von Winkle recalls that the NLDC “evicted [the tenants] physically,” and “put people in the street with their socks with no shoes.”60 The NLDC also “put cement barriers in front of the house that made it impossible to rent.”61

Richard Beyer’s tenants were handed eviction notices by city officials and were repeatedly harassed by police officers and other city employees. Some chose to leave because they “wanted to live their life peacefully.”62 Matthew Dery recalls that city employees demolished the already sold building behind his house in a way that caused its wall to collapse onto his garage, thereby destroying it.63 Michael Cristofaro told me that he and his parents were repeatedly “harassed” by NLDC representatives, including by means of “constant telephone calls late at night” that he believes were intended to intimidate the family.64

Susette Kelo remembers similar incidents. “Every day,” she said, “we were pressured” to leave. “The wolves were at our door . . . They did everything they could possibly do” to force reluctant homeowners to sell.65 On one occasion, Byron Athenian arrived at home and discovered that dump trucks had “unloaded tons of dirt in the street right in front of his house,” making it impossible for him to move his handicapped granddaughter’s wheelchair from the house to the road and creating an overwhelming cloud of dust that covered the inside of his house.66 Bill Von Winkle stated that the harassment “went on for seven years on a daily basis.”67

Some of those property owners who did agree to sell were subjected to similar pressures. Marguerite Marley told me that her family, too, was harassed and that neighbors’ homes were “broken into.” They found the experience “intimidating” and ultimately agreed to sell in part because of such tactics.68 When they finally did sell, on a Friday, city officials shut off the utilities by Monday, even though they had given the family a week to move.69

A 2002 Wall Street Journal article recounted interviews with several elderly residents who ended up selling despite the fact that they preferred to stay.70 One bitterly lamented that he was forced to leave an area where he had lived for seventy-five years; another elderly resident—a World War II veteran—stated that he wished he could have resisted the NLDC, but could not put up a fight because “I am old.”71 Scott Sawyer, a lawyer who later helped file a lawsuit challenging the NLDC plan on environmental grounds, recalled that the residents “were mostly elderly, and they were scared to death.”72 One elderly longtime resident told Sawyer that he did not wish to resist “because I do not have the fight in me.”73 Erika Blescus, a neighbor of Susette Kelo’s who had lived in the area for 28 years, agreed to sell after resisting for over a year because, according to The Day, she had come to believe that further resistance was likely to be futile.74

Michael Cristofaro notes that those who ultimately resisted the takings were all either relatively young themselves or had younger relatives to uphold their interests, as in the case of his own parents and the Derys. Other elderly residents, he believes, did not “have the strength” to fight back and “make it last for 6-7 years.”75

There is no way to know for sure how many of Fort Trumbull property owners would have been willing to sell their land in the absence of the threat of eminent domain and other coercive tactics used against them.

I do not doubt that at least some would have been willing to sell without any coercive inducement.76 But it seems likely that at least a substantial minority would have refused to sell at the prices offered. The fact that the NLDC believed that the threat of eminent domain was a necessary tool and that they resorted to other forms of coercion is in itself suggestive.

Whether voluntarily or not, most of the property owners in the Fort Trumbull area eventually agreed to sell their land to the NLDC. But seven refused: Susette Kelo, the Cristofaros, the Derys, Richard Beyer, Bill Von Winkle, Byron Athenian and his mother, and Laura and James Guretsky.77 A combination of attachment to their properties and anger at the strongarm tactics used by the NLDC led them to dig in their heels and resist. Beyer, for example, said that he chose to fight partly to protect his and his business partner’s investment, and partly because he “wasn’t going to allow someone to railroad me.”78 The Derys and Cris-tofaros fought primarily to enable their elderly parents to keep properties that they had owned or lived in for many decades.79 Between them, the resisters owned fifteen residential properties in the Fort Trumbull area that were scheduled for inclusion in the Municipal Development Plan.80

Working together, the seven owners tried to stop the condemnations through political activism and organizing. They managed to attract considerable support from others in the community, including former New London Mayor Lloyd Beachy, who sympathized with them and opposed the use of eminent domain to force them out.81 Beachy believed that redevelopment should be conducted without forcing people out and that the use of eminent domain was inconsistent with Claire Gaudiani’s and the NLDC’s stated commitment to “social justice.”82 He also feared that condemnation and demolition of existing homes would result in the construction of “a plastic village that nobody will want to be at.”83 But Beachy, the only member of the city council to vote against authorizing the use of eminent domain, was an exception to the local political establishment’s otherwise strong support for the planned condemnations.

Despite lack of support from the city’s political leaders, the Fort Trumbull property owners did manage to attract considerable local public sympathy. Their allies formed the Coalition to Save Fort Trumbull Neighborhood to try to prevent the takings.84 The group used petitions, protests, and other activism to try to force the city and the NLDC forego the use of eminent domain.85 One of the leaders of the group was Frederick Paxton, a history professor at Connecticut College—the very same college of which

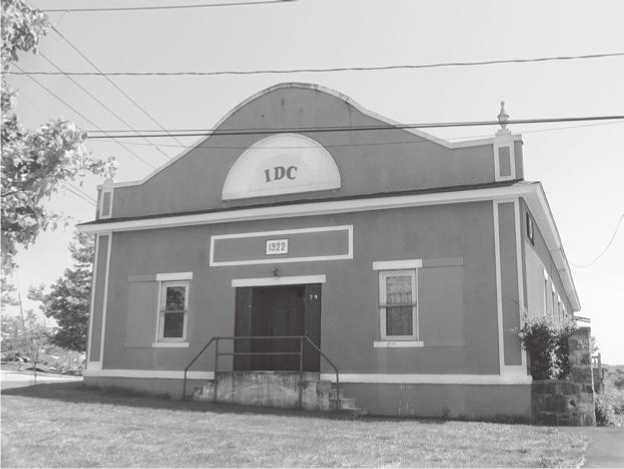

Figure 1.4 The Italian Dramatic Club. (Credit: Ilya Somin.)

NLDC chair Claire Gaudiani was the president.86 Paxton believed that Fort Trumbull could be redeveloped without using eminent domain to force out unwilling homeowners. “It just didn’t make any sense,” he recalled, “to go through the pain and suffering and trouble of getting people out of their homes who didn’t want to leave.”87 The Coalition included other participants from a wide range of backgrounds, and “all over the political spectrum”—including some on the political left who believed it was wrong to force out people for the benefit of politically-connected business interests.88

Despite the efforts of the Coalition, the resisting property owners ultimately had little success in influencing the NLDC to change its plan. By contrast, the Italian Dramatic Club, a private men’s club located in the redevelopment area, which was a “hot spot for politicians seeking votes and financial support,” was able to use its political clout to get an exemption from the threat of eminent domain.89 The exclusion of the Italian Dramatic Club undercuts claims that the NLDC genuinely needed to take every single property in the development area in order to carry out their development plan.

The Legal Battle

Realizing that they were up against powerful political interests stronger than themselves, the resisting owners began to consider the possibility of fighting the takings in court. They approached various local eminent domain lawyers, all of whom either refused to take the case outright or demanded extremely high fees that the owners could not pay.90 Richard Beyer retained a local firm, only to have them withdraw later, having told him that “you don’t have enough money to fight this.”91 The property owners would likely have had to give up the fight if not for the intervention of the Institute for Justice, a libertarian public interest law firm focused on strengthening judicial protection for individual freedom, with a special focus on property rights and economic liberties.92 The Institute for Justice was initially contacted by Peter Kreckovic, a local landowner, amateur artist, and historic preservationist who had joined the Coali-tion.93 Kreckovic had learned about the Institute from John Steffien, another paricipant in the group.

IJ’s top property rights litigators Dana Berliner and Scott Bullock had long been searching for cases that could promote stronger judicial enforcement of public use constraints on eminent domain. Their most notable early victory was a 1998 case in which the Institute had represented a New Jersey woman who sought to prevent the condemnation of her home for the construction of a casino owned by controversial developer Donald Trump.94 Berliner and Bullock knew that the Supreme Court had ruled in Berman v. Parker (1954) that virtually any interest asserted by the government could qualify as a public use under the Fifth Amendment and reaffirmed that position in Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff in 1984.95 But they believed that the intellectual winds had begun to shift since then and that Berman and Midkiff were poorly reasoned precedents whose reach the Supreme Court might be willing to restrict if presented with an appropriate case.96

Bullock visited New London in August 2000, and met with the resisting property owners and their supporters. He concluded that the dispute was potentially a good opportunity for IJ. The Fort Trumbull case was attractive to IJ for three reasons.97 First, the NLDC and the city did not claim that the properties they sought to condemn were “blighted.” The public purpose for which the land was being condemned was purely “economic development.” This potentially differentiated the case from

Berman v. Parker,98 the key 1954 Supreme Court decision upholding the condemnation of blighted property and endorsing a broad interpretation of “public use.” Although the IJ lawyers believed that the Court might be willing to cut back on Berman’s logic, they doubted that there would be a majority for invalidating blight condemnations as well as economic development takings.

Second, the New London property owners were determined to fight to keep their land and unlikely to sell out in exchange for a higher compensation award. Berliner and Bullock were deeply impressed by their commitment and determination. They needed committed clients who would be willing to litigate the case to the point where it resulted in a published opinion that, in the event of victory, would serve as a valuable precedent protecting property rights in future cases.

Finally, the Institute’s lawyers recognized that the New London property owners and their case would play well in the court of public opinion as well as the courtroom. As part of its litigation strategy, IJ had long emphasized the need to win public sympathy for its cause, an approach previously pioneered by liberal public interest groups such as the NAACP.99 John Kramer, IJ’s vice president for communications, notes that a good case should have “compelling clients, very simple facts, and outrageous acts.”100 As homeowners and small businesspeople opposing powerful governmental and corporate interests who had resorted to aggressive pressure tactics, the Fort Trumbull owners fitted that model well. For all of these reasons, IJ decided to take up the New London litigation. In Bullock’s words, it was “an ideal public interest case.”101

All of the resisting property owners are emphatic in their belief that they could never have taken the case as far as they did without IJ’s inter-vention.102 As Susette Kelo described it, IJ “put us on the map.”103 Bill Von Winkle emphasized that “IJ is absolutely the best at fighting for people’s rights” and that “there is no comparable lawyer.”104 It is indeed true that few other lawyers have comparable expertise in litigating public use cases.

Peter Kreckovic of the Coalition to Save Fort Trumbull Neighborhood also emphasizes that the movement to oppose the takings would probably have collapsed without IJ’s assistance. In the period just before the Institute became involved in the case, “we were,” as he puts it “pretty much at the end of the rope” and “wouldn’t have gotten anywhere without [IJ].”105

The Institute’s lawyers provided topnotch legal representation pro bono. In addition, as a public interest firm with extensive public relations expertise, IJ helped generate extensive sympathetic media attention for the case. Ultimately, the Institute spent some $600,000 to $700,000 litigating the case even before it reached the federal Supreme Court and as much as $1 million in all.106 It is highly unlikely that the resisting property owners could have come up with that kind of money on their own. Even if they could, they might not have been able to find a conventional law firm able to replicate IJ’s performance in both the courtroom and the court of public opinion.

Even with IJ’s assistance, the property owners found the long struggle with the city and the NLDC extremely burdensome. The uncertainty of not knowing whether they could keep their homes and other property was difficult to bear. In addition, the litigation was extremely stressful and time consuming. As Susette Kelo put it, “[a]ll we did for eight years, was eat and drink eminent domain . . . that’s what we thought about all day long.”107 Matt Dery notes that “[s]ix years with your nuts in a vise is really a long time.”108 Bill Von Winkle recalls that “for seven or eight years, [he] was frozen financially” because he did not have control over the deeds to his property.109

Since neither the NLDC nor the property owners were willing to give in, the case went to trial in Connecticut Superior Court, before Judge Thomas J. Corradino. During the trial, the Institute for Justice lawyers presented evidence pointing to Pfizer’s role in the takings. This material included statement by James Hicks, executive vice president of a firm that helped develop the New London development plan, indicating that Pfizer was the “10,000 pound gorilla” behind the project.110 They also contended that the condemnations exceeded New London’s powers under state law, that the taking of the seven plaintiffs’ properties was not necessary to achieve the goals of the development plan, and that it violated the public use clauses of the federal and state constitutions. For their part, the NLDC and New London contended that the development plan was intended to benefit the public, not Pfizer, that the condemnations were needed to implement it, and that they were entirely constitutional.111

On March 13, 2002, Judge Corradino issued a complex 249 page opinion that invalidated the condemnation of eleven of the fifteen properties at issue, while upholding that of the other four.112 Corradino began by rejecting the Institute for Justice’s argument that the transfer of property to a private party for “economic development” is not a public use under the state and federal constitutions; he instead endorsed a broad interpretation of “public use” that encompassed virtually any potential public benefit.113 Although he conceded that the record on this point was “a mixed one, if not rather confusing,”114 Corradino ruled that he could not “conclude that the primary motivation or effect of this development plan . . . was to benefit this private entity.”115 But this conclusion was reached without complete knowledge of the full extent of Pfizer’s role in shaping the development plan, which only became publicly known in 2005.116 It is difficult to say whether the 2005 revelations would have made a difference to the judge’s conclusion on this point or not.

Corradino nonetheless invalidated the condemnation of the eleven plaintiff-owned properties in the area designated as Parcel 4A on the grounds that the development plan’s projected uses for the area “are so vague, shifting, and noncommittal” that the city could not prove that its condemnation was actually necessary to pursue the objectives of the development plan.117 At various times, NLDC officials had suggested that the area might be used for a museum, for parking, or for “park support,” but there was no clear plan to effectively use the property for any of those purposes.118 The properties owned by Susette Kelo, the Derys, the Guretskys, and Bill Von Winkle were all located in Parcel 4A and therefore had escaped condemnation.119

The other three plaintiffs’ land, however, was on Parcel 3, which the NLDC planned to transform into office space.120 Here, Corradino concluded that the plan was specific and detailed enough to prove that condemnation was necessary to carry it out.121 Byron Athenian, Richard Beyer, and the Cristofaro family had therefore lost.

The split decision did not completely satisfy either side. In the aftermath, the NLDC offered the property owners a settlement under which they promised not to appeal the part of the ruling invalidating the takings on Parcel 4A, if the property owners agreed not to appeal the part upholding the condemnations on Parcel 3.122 Although NLDC leaders would have preferred to appeal the case, they yielded to pressure from the New London city council, which preferred to settle.123

The offer presented the plaintiffs with a difficult decision. Accepting it would mean sacrificing the three members of their group who had suffered a defeat. For the Institute for Justice, it would mean giving up the possibility of getting an appellate decision holding that economic development takings are unconstitutional. But rejecting the deal risked losing the victory that had been achieved for the owners with property on Parcel 4A.

Critics of the Institute for Justice contend that IJ persuaded the Parcel 4A property owners to sacrifice their own interests for the purpose of advancing the Institute’s broader property rights agenda.124 It is indeed true that the IJ lawyers wanted to create a favorable public use precedent and that failure to appeal would have undercut that objective. However, the owners themselves believed that they had little to lose by appealing because the NLDC refused to abjure the use of eminent domain against them in the future.125

In the immediate aftermath of the trial court decision, NLDC executive David Goebel stated that the agency still intended to include Parcel 4A in its redevelopment plan and would use eminent domain to acquire it if the owners refused to sell.126 Since Judge Corradino had invalidated the takings only because the NLDC’s plan for Parcel 4A was not specific enough, the possibility existed that it could resort to eminent domain again after revising the plan to make it more precise, or creating a new, more detailed plan.127 Mayor Lloyd Beachy, who was then serving his second term in the office, urged the NLDC and the city council to “take eminent domain off the table,” as did one other member of the city council, former Mayor Ernest Hewett, who had previously supported the use of eminent domain.128 But this advice was not followed.

Matthew Dery realized that IJ “had their agenda.” But he and his family ultimately decided to support the appeal because he recognized that the trial court decision may only have been “a stay of execution.”129 Moreover, after the NLDC’s previous actions, he “wouldn’t have trusted anything they said.”130 Bill Von Winkle expressed similar sentiments in almost exactly the same words.131 Dery, Von Winkle, and Susette Kelo, also wanted to appeal out of solidarity with the three property owners who had lost in the trial court, with whom they had already spent years fighting in a common cause together.132

For these reasons, the property owners ultimately decided to reject the NLDC offer. However, they and their IJ lawyers responded with a counteroffer under which the Parcel 3 owners would agree not to appeal in exchange for city financing for moving their homes to a new location, and a guarantee that the properties on Parcel 4A would be taken out of the redevelopment plan, and eminent domain would not be used against them in the future.133 The NLDC and the city refused this counteroffer.134 Had they been more open to it, it is difficult to say whether the two sides could have agreed on a mutually acceptable formula for the relocation expenses for the Parcel 3 owners.

Ultimately, the two sides could not come to a mutually acceptable agreement. The plaintiffs appealed their case to the Connecticut Supreme Court. For their part, the city and the NLDC appealed their defeat over Parcel 4A.

The Supremes

On March 9, 2004, the constitutionality of the plan was upheld by the Supreme Court of Connecticut in a close 4-3 decision.135 The majority endorsed the view that “economic development” under private ownership is a permissible public use under the federal and state constitutions.136 It also upheld the takings on both Parcel 3 and Parcel 4A as being “reasonably necessary” to achieve the goals of the NLDC’s development plan under a standard of review that is highly deferential to the decisions of the government.137

In a prescient dissent joined by two of his colleagues, Justice Peter Zarella agreed that economic development by private parties might be a legitimate public use. But he emphasized that such takings require “a heightened standard of judicial review . . . to ensure that the constitutional rights of private property owners are protected adequately.”138 This is because

Economic growth is a far more indirect and nebulous benefit than the building of roads and courthouses or the elimination of urban blight. Indeed, plans for future hotels and office buildings that purportedly will add jobs and tax revenue to the economic base of a community are just as likely to be viewed as a bonanza to the developers who build them as they are a benefit to the public. Furthermore, in the absence of statutory safeguards to ensure that the public purpose will be accomplished, there are too many unknown factors, such as a weak economy, that may derail such a project in the early and intermediate stages of its implementation.139

If economic development qualifies as a public use, Justice Zarella believed that courts should police the political process to ensure that the economic development used to justify a taking is actually achieved by it. Otherwise, there would be too great a risk that the taking in question was merely intended to benefit a private interest at the expense of the general public: “[T]he constitutionality of condemnations undertaken for the purpose of private economic development depends not only on the professed goals of the development plan, but also on the prospect of their achievement.”140

Zarella’s dissent went on to conclude that the Fort Trumbull takings failed to meet this standard. At the time of the condemnation, he pointed out, there was no signed development agreement providing for the future exploitation of the condemned property, a circumstance that greatly reduced the chances of actually producing any economic development and made it “impossible to determine whether future development of the area primarily will benefit the public or will even benefit the public at all.”141 The NLDC had selected Corcoran Jennison as the designated development firm for the area, but had not signed any development agreement or even come close to concluding one by the time of the trial.142 Justice Zarella also pointed out that the proposed development plan imposed few restrictions on the new private owners of the condemned property and flew in the face of market conditions that made it unlikely that the city would be able to reap significant economic benefits from the condemna-tions.143 In weighing the expected economic benefits of the plan, the city failed to even consider “the loss in revenue that could result from the relocation of former residents and taxpayers out of the area” or to weigh the loss of $80 million in public funds (mostly from the state government) that had been committed to the project.144 Zarella’s fears that the condemnations would fail to produce the promised development would be amply justified by events.145

The majority’s decision was in part dictated by its refusal to consider the possibility that the Connecticut state constitution provides stronger “public use” protections against takings than the US Supreme Court’s interpretation of the federal Constitution.146 The majority followed the court’s previous practice of refusing to consider the possibility that the state constitution provides more protection for individual rights than a similar provision in the federal Constitution, unless the parties to the case explicitly raise the issue.147

It is true that IJ’s brief in the state supreme court did not specifically state that the Connecticut constitution provides greater protection for property owners than the federal one. However, much of IJ’s argument was explicitly based on state public use precedent, as was also the case with the arguments advanced in Justice Zarella’s dissent.148 In his 2008 book, The History of the Connecticut Supreme Court, Wesley Horton—a leading Connecticut attorney who eventually represented New London before the federal Supreme Court—criticized the state supreme court majority for refusing to even consider the possibility that the state constitution provided greater protection than the federal one.149 As he noted, “[g]iven that the court took well over a year from oral argument to decision, and given that Zarella’s dissent reads as it if were resolving a state constitutional question, the court would have avoided the subsequent national controversy if it had asked for modest supplemental briefing and if it had then found merit in the plantiffs’ state constitutional claim.”150 Such supplemental briefing might not even have been necessary, given that the two sides had already extensively discussed relevant state court precedents in their original briefs.151

Disappointed by their narrow defeat in the state supreme court, the plaintiffs and the IJ lawyers decided to petition the federal Supreme Court to consider the case. Since the Connecticut Supreme Court had ruled that the takings were permissible under the federal Constitution as well as the state one, the federal Supreme Court had jurisdiction to hear the case, should four of the nine justices vote to grant the plaintiffs’ petition for certiorari. But the Court only grants a tiny fraction of the thousands of petitions that reach it each year.

To write its brief opposing the property owners’ petition for certiorari, New London brought in Wesley Horton, a highly respected appellate lawyer who had advised the city earlier in the litigation. Like his adversaries Berliner and Bullock, Horton had not previously handled a case in the U.S. Supreme Court. But he had argued over one hundred cases in Connecticut’s state supreme court and was one of the state’s best appellate litigators.152 In 2001, he had represented a property owner who lost an eminent domain case in the state supreme court, in an unsuccessful effort to persuade the federal Supreme Court consider the issue.153

Like most experts, Horton believed it was very unlikely that the Court would agree to hear the case. For this reason, he agreed to write the opposition brief for what was, for a lawyer of his credentials, the modest fee of $10,000.154 Should the Court take the petition, he committed to handling the case without any additional payment.

My own expectations at the time were similar to Horton’s. Having followed the case from a distance, I too doubted that the Supreme Court would be willing to take it. Because the Court had long endorsed an extremely broad view of public use similar to that embraced by the Connecticut Supreme Court in Kelo,155 I thought it unlikely that it would wish to reconsider it. That expectation was reinforced by the fact that Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a key swing voter on property rights and other issues, was also the author of the Court’s ruling in Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff, a 1984 Supreme Court decision reaffirming the broad interpretation of public use.156 To the surprise of many, the Court nonetheless granted the petition for certiorari on September 28, 2004. IJ and its clients had a new lease on life, and Horton would have to do a lot more work to earn his $10,000.

The Supreme Court’s decision to take the case attracted a new wave of media and public attention.157 At the same time, many organizations and activists involved with eminent domain and property rights issues began to realize that the case was likely to set an important precedent. An unusually high total of thirty-seven amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs representing some one hundred different organizations were filed in the Supreme Court case, twenty-five of them on the side of the property owners and twelve supporting New London.158

The coalition of amici supporting the property owners included some surprising bedfellows. In addition to conservative and libertarian property rights advocates, there were a number of prominent left of center amici. The NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (a historic civil rights organization of mostly African American clergy), the AARP, and the Hispanic Alliance of Atlantic County filed a joint amicus brief emphasizing the negative impact of eminent domain on the poor, minorities, and the elderly.159 I myself authored an amicus brief on behalf of Jane Jacobs, the legendary progressive urban development theorist who had been a leading critic of blight and economic development takings since the 1960s.160 Many of the amicus briefs on the other side were filed by organizations representing development planners and state and local governments, such as the American Planning Association, The National League of Cities, the National Council of State Legislatures, and the U.S. Conference of Mayors.161 These groups had an obvious and understandable interest in minimizing judicial scrutiny of the exercise of their eminent domain authority.

On February 22, 2005, the Supreme Court held oral arguments in Kelo, in which the contending lawyers could present their positions before the justices in person. Horton conducted the argument for New London, while Scott Bullock did so on behalf of the plaintiffs. While most Supreme Court cases are decided primarily on the briefs submitted before oral argument, the arguments are closely watched by experts, because they are often an important gauge of the justices’ attitudes. So it proved in this case.

The justices asked tough questions of both sides, pressing Bullock on the possibility that his position was not sufficiently deferential to the government and Horton because the economic development rationale for takings seemed to leave no room for meaningful limits on the scope of eminent domain. By far the most widely noted moment in the oral argument occurred when Justice Sandra Day O’Connor asked Horton whether the economic development rationale would allow condemnation of “a Motel 6 [if] a city thinks ‘if we had a Ritz-Carlton, we’d get higher taxes.’ ” Horton answered that that would be “OK.”162 When Justice Antonin Scalia followed up by asking whether “[y]ou can take from A to give to B if B pays more taxes,” Horton reiterated his position, stating that such a taking would be permissible if the difference in tax revenue is “a significant amount.”163

This answer is often seen as a mistake on Horton’s part and may have helped cost him Justice O’Connor’s vote. O’Connor cited the Motel 6/Ritz Carlton example in her dissenting opinion as an illustration of the unbounded nature of the economic development rationale for takings.164 Scott Bullock believed that Horton’s answer played into the plaintiffs’ hands.165 Michael Cristofaro, who attended the argument, thought that Horton sounded like he “was working for us.”166

Whether or not it was an error, Horton’s answer to this question was carefully planned in advance. He had considered this exact issue in preparing for oral argument and had deliberately decided to concede the point rather than be forced to “spend ten minutes” addressing various potential hypothetical situations in what he feared might be a very difficult attempt to try to draw a line that would impose meaningful public use constraints on takings but would not lead to defeat for his clients.167 He instead preferred to spend his limited time focusing on “the facts of my case,” especially the extent to which the takings were part of a carefully produced development plan organized by a nonprofit entity accountable to the city rather than a proposal put forward by a private developer seeking to advance his or her own interests.168

Horton’s strategy did ultimately lead to victory. In my view, it is indeed true that there are no meaningful limits to the economic development rationale, and therefore an effort to constrain it would ultimately be futile.169 Moreover, Horton’s emphasis on the extent of New London’s planning process would be echoed in the Court’s majority opinion.170 Overall, Horton’s approach was probably correct from the standpoint of maximizing his chances of winning. It was a risky but arguably effective “tactical decision” that enabled him to spend his oral argument time focusing on the strong points of his case rather than its main area of weak-ness.171 On the other hand, however, the answer may have cost him the support of Justice O’Connor, a key swing voter who—along with Justice Anthony Kennedy—was one of the members of the Court Horton most wanted to persuade.172 O’Connor’s forceful dissent and the closely divided nature of the Court’s decision would play a key role in shaking the dominance of the conventional wisdom in favor of broad judicial deference to the political process on public use issues.173 Moreover, as Horton acknowledges, his Motel 6-Ritz Carlton answer figured prominently in media accounts of the argument,174 exemplifying the potential for eminent domain abuse inherent in New London’s position.

Conclusion

The Kelo oral argument was the end of an improbable path by which an initially obscure eminent domain case had reached the U.S. Supreme Court, with the potential to undercut long-standing precedent allowing government to condemn property for almost any reason. Despite the Ritz-Carlton/Motel 6 exchange, many initial reports after the oral argument suggested that the justices were unlikely to rule in favor of the property owners.175 Wesley Horton came away from the argument believing that he had probably secured what he thought would be Justice O’Connor’s decisive vote, though he also believed that the three most conservative justices—Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Chief Justice William Rehnquist—would probably vote against him.176

Ultimately, the Kelo case turned out to be a lot closer than he and many others expected. Although New London won a nail-biting 5-4 victory, the close and controversial nature of the outcome would help undermine the long-standing conventional wisdom that public use constraints on eminent domain were a thing of the past. In the next chapter, we explore how that view became conventional wisdom in the first place.