Chapter 1

Taking a Look at Your Sleep

If you have read other books on insomnia or talked with your doctor about your sleep problems, chances are you have been advised to do a number of things—limit caffeine and alcohol, have a wind-down routine before bed, use your bedroom only for sleep and sex, and so on. You may have found it challenging to navigate all the advice. (How much caffeine is okay? Should you really stop reading in bed even though it helps you get sleepy?) And since you really want to sleep well, you may have gotten focused on getting it “right.”

Effectiveness as Your Compass

When we are asked a question (“Should I cut out my naps?” “When I wake up in the middle of the night, should I stay in bed or get up and do something?”), our most frequent answer is, “It depends.” There is not a single right answer, nor a wrong way to do things. We can give you our best educated guess, based on what we understand about sleep physiology, and we will be doing that throughout the book. These recommendations will be helpful, on average. But you are not average. You are you. And you today, with your current health, life stresses, activities, and habits, are not exactly the same as you six months from now.

So when it comes to giving advice about your sleep, it is all about what works, not about rigid rules that apply to everyone. However, it is about what works in the long run, not just what works today. Things that give you short-term relief, such as a daytime nap, often come at the price of keeping insomnia around longer (much more about this in chapter 2).

We use the word “effective” to capture this idea of what works in the long run. You will notice that we use this word a lot in this book! We will help you use effectiveness as your compass to guide your treatment program.

But how will you know what truly works for you? Our mantra here is, Collect the data! And that is what this chapter is all about. You need data to help you choose the treatment elements best suited to your sleep problems, which will make this treatment work better, and more quickly, than a one-size-fits-all approach. Data also will help you monitor the impact of treatment, keep up your motivation, and guide the pace and direction of your program.

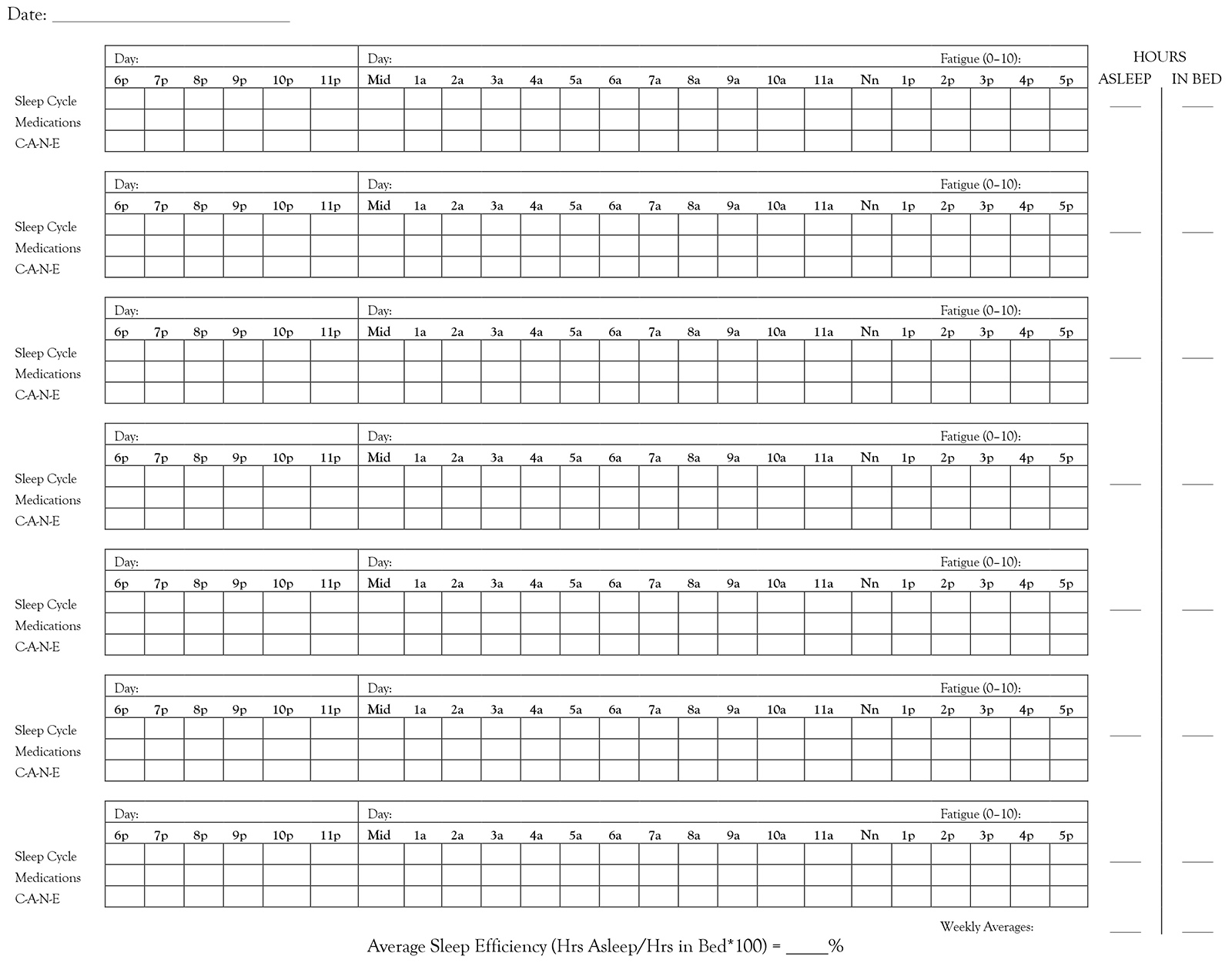

Sleep Log

A sleep log or sleep diary is the most important data collection tool for this treatment. It will help you recognize patterns in your sleep and track the impact of treatment. Because you will ideally collect data for ten to fourteen days before designing your treatment program in chapter 5, we want to encourage you to start now! In worksheet 1.1 we provide a sleep log that we have developed and tweaked over a number of years, as well as detailed instructions. We also provide an example of a completed sleep log. Take a look. A warning: the instructions are very detailed! We encourage you to take your time. You will get more benefit from your sleep log the more specific and accurate you are.

Once you have reviewed the log, instructions, and sample, return here for some additional guidance.

Instructions:

- In the upper left corner, fill in the date of the first day. This will help you keep your weeks in order.

- Complete this log twice daily—at night (to record your daytime information) and again first thing in the morning (to record your nighttime information).

- Fill in the days of the week that correspond to the hours of 6 p.m.–midnight, and to midnight–5 p.m.

- Sleep Cycle: In this row, record information about when you are in bed, when you sleep, and when you wake up. Include both your nighttime sleep and daytime naps. Use this key:

- Time(s) you got into bed (at beginning of night, and if you leave and return to bed in middle of night).

- * Time you turned the lights out (only mark if different from the time you got into bed).

- — Time you believe you were asleep (use a squiggly line ~~~ to indicate light, fitful sleep).

- | Middle-of-the-night awakenings.

- Time(s) you got out of bed after lights out (including end of sleep period).

- Medications: In this row, record all prescription and over-the-counter medications, including dose. You can create a key and use abbreviations (for example, m = melatonin; a5 = Ambien 5 mg).

- C-A-N-E: In this row, record the time and amount of Caffeine, Alcohol, Nicotine, and Exercise. For caffeine and alcohol, list the number of drinks (for example, C2 means two cups of coffee or two Cokes; A3 means three beers in this hour). For nicotine, indicate number of cigarettes or amount of chew. For exercise, indicate number of minutes.

- Hours Asleep: Record your best estimate of the total number of hours you were asleep at night (do not include daytime naps). Include fitful sleep (squiggly line).

- Hours in Bed: Record your best estimate of the total number of hours you were in bed at night and attempting to sleep. For example, do not count time you spent reading in bed at the beginning of the night if this was simply part of your bedtime routine. Do count time spent reading if you were reading because you could not sleep and hoped to fall asleep while reading.

- Fatigue: Rate the amount of fatigue you experienced on the day that corresponds to Midnight–5 p.m. 0 = No fatigue… 10 = Extreme fatigue.

- Averages: At the end of the week, calculate and record your averages. (a) Add up your Hours Asleep and divide by the number of nights for which you have this data. Record your average. (b) Do the same for Hours in Bed. (c) Calculate and record your Sleep Efficiency (Average Hours Asleep divided by Average Hours in Bed, multiplied by 100).

Common Questions (and Answers) or Roadblocks (and Possible Solutions)

“I do not want to look at the clock once I’m in bed. I’m afraid it will make me more anxious.”

We agree that it is not useful to clock-watch. Fill in your sleep log as best you can, without getting caught up in having to be exactly right. For example, if you fall asleep around midnight and wake up at 3 a.m., and you know that you had two brief awakenings in between, put two vertical lines sometime between midnight and 3 a.m., even if you do not know precisely what time it was. Knowing that you woke twice is more important than knowing that you woke at 1:12 and 2:38!

Note, however, that people with insomnia tend to underestimate how much sleep they get. This means they overestimate how long it takes to fall asleep or for how long they are awake in the middle of the night. Therefore, you may decide to collect more accurate data.

If you do not want to look at the clock when you wake up too early, you can have a stopwatch at the ready. When you wake up, hit the start button. Then, when you get up for the day, you can see how much time has passed. If you get up at 7 a.m. and your stopwatch says two hours and fifteen minutes, then you know you woke up at 4:45 a.m. Or if you have multiple awakenings you want to record rather than just one, you can try what one of our clients did: he pressed the “memo” button on his smartphone any time he woke up; in the morning he was able to see the timestamp of all the memos he created.

A simpler option is to just glance at the clock. You may find that this is not nearly as anxiety provoking when you are doing it for the purpose of treatment, rather than wondering when the heck you are going to fall asleep!

Be flexible. If you are concerned about looking at the clock, try it both ways. Complete the log using your “best guess” for a few nights. Then complete it while tracking time for a night or two. Which do you think is more helpful? Does tracking time make you more anxious or alert? If so, are you willing to have a small uptick in your anxiety for a few nights? Or is the cost greater than the potential gain?

“I forgot.”

Try to pair completing the sleep log with something else you do each and every morning and night. For example, if you use the bathroom morning and night, you can put on your bathroom mirror a sticker that reminds you to complete your sleep log. If you take medications or supplements at night and always start your day with coffee, you can put the sleep log or a reminder with your medications and near your coffee pot.

Leave your sleep log somewhere visible, such as on your bedside table. Have a pen or pencil with it. Some people like to have it on a clipboard, to make it easier to spot in a pile of clutter, and easier to write on.

You also can set a daily alarm on your watch or phone, or have a pop-up reminder on your computer. Pick the device you are most likely to see or hear first thing in the morning and later at night.

“I forgot for a few days. Should I go back and fill in the data that I missed?”

In general, we think that having no data is better than having inaccurate data. If you miss some days, fill in any information in which you are extremely confident. For example, if you use a pillbox and always take medications at the same time when your watch alarm beeps, you can look at your pill box and confidently fill in information about what medications you took when. Perhaps your exercise is in your calendar and you remember sticking to that schedule, and you can complete that. It may be more difficult to accurately recall how fatigued you were a couple of days ago, so you may want to leave that blank. In other words, do the best you can, but leave blank anything that requires guesswork. Our memories are quite fallible!

“Is it okay to complete the log once a day instead of twice?”

Most people find that if they try to complete the log only at night, they do not have as good a memory for their sleep the night before. So for most people we suggest completing the log soon after waking to record sleep the night before, and at night to record daytime fatigue and behaviors. If you find that in the morning you can easily remember all the information you need to record for the day and night before, then it is fine to complete it only in the morning.

“I don’t have time.”

After a couple of days of using the log it will probably take you one or two minutes at night and one or two minutes in the morning. Considering how important the sleep log is, and what your insomnia is already costing you, we hope you will agree that it is worth an investment of less than five minutes per day.

“I’m using a phone app or wearable fitness device that uses my movements to record my sleep pattern. Do I still need to complete this log?”

We strongly recommend that you complete a paper-and-pencil sleep log like the one we have included here. Different devices people use to record their sleep seem to come up with different results, and we do not know which devices or applications are most accurate. Also, some of the apps that our patients have used do not provide all of the data that you will need to guide your treatment program. Finally, using a log like the one we have provided may help you see patterns only obvious when you look at the data a week at a time, and with the sleep data right next to the data about the medications you took or other behaviors, such as alcohol and caffeine use.

“Should I track medications I take for things other than sleep?”

Yes! We encourage you to record all medications and supplements, whether prescription or over-the-counter. You may see that you are taking an activating medication (such as the antidepressant Wellbutrin [bupropion], or a decongestant such as pseudoephedrine) too late in the day. Or maybe a medication you take in the morning (such as a blood pressure medicine) makes you feel tired, so that you think you did not get adequate sleep, when really you did. You may want to consult with a physician or pharmacist to help you better understand the impact medications or supplements may be having on your sleep or fatigue.

“What should I include in my total Hours Asleep?”

Include all nighttime sleep. Include sleep that is fitful. Include sleep you got somewhere other than your bed. But do not include daytime naps. This means you are including all the time at night that is marked with a straight or squiggly line.

“Why should I count fitful sleep in my total hours of sleep? Won’t it look like I’m getting more sleep than I am?”

You are right that it is not always clear whether fitful sleep should “count.” We usually include it in the estimate of total sleep time because research shows that, on average, people with insomnia underestimate how much sleep they get. Also, as strange as this may sound, it is possible for you to be technically asleep even though part of your brain is alert and aware of passing time!

If you are concerned that counting fitful sleep will paint an inaccurate picture, then you can run the numbers both ways. Track your total sleep hours including fitful sleep, and your total hours of only more solid sleep. Then calculate two weekly averages—one for all sleep and one for more sound sleep—for both your total sleep time and your sleep efficiency. You will be able to decide over time which is the more useful or meaningful measure.

“Why should I track all of my time in bed, but only count in my total time in bed the hours that I am attempting to sleep?”

When we explain later in this book the theories behind stimulus control therapy and sleep restriction therapy, you will see that spending too much time awake in bed may be maintaining or worsening your insomnia. It is useful to see just how much time you are spending in bed. However, when calculating sleep efficiency, it is more useful to count in your total hours only the amount of time that you are attempting to sleep. You will be using your sleep efficiency data to help guide your behavioral treatment program.

“It is painful to see how poorly I’m sleeping. It stresses me out to look at the data.”

Unfortunately, this work—whether it be the sleep log or the treatment program—may be uncomfortable or painful at times. We wish there was an easier, more comfortable, but just as effective way to help people with insomnia sleep better again. There is not. We hope it helps to know that this is likely to be short-term pain, with long-term gain.

“I just don’t want to!”

It is your choice. You can choose to not track your sleep. You do not have to do anything we suggest. And not tracking will maintain the status quo. You are reading this book because you want something to be different in your life. It starts with doing some different things, even when you don’t want to. The good news is that you probably have lots of experience doing things you don’t want to do. Paying taxes comes to mind as an example!

Your mind can tell you, Do not do it, or I don’t want to, and you can do it anyway. Try this exercise: say “I don’t want to nod my head” three times, and on the second time, start to nod your head, even while saying that you don’t want to. Silly, we know, but give it a try. What do you think: can you keep a sleep log even though you don’t want to?

Are You Willing to Start the Sleep Log?

If your answer is yes, we encourage you to make some preparations to set yourself up for success. Download additional copies of the sleep log from http://www.newharbinger.com/33438. Decide where to put the log, and put a pen or pencil with it. Set up any reminders you think you need. Go ahead and get started! Then continue with the rest of the assessments in this chapter.

If you are not willing, carefully consider why. What are your specific concerns, fears, or obstacles? See if you can problem-solve or work through these. If you cannot (that is, you still are not willing), please skip to chapter 4 now. See if the discussion about acceptance and willingness increases your willingness to do the sleep log, even if just for a week. You do not have to commit to anything long term. You can collect some data about what it is like to collect the data!

If you still are not willing to keep a sleep log, you may benefit from using the skills in part 3 (Cognitive Strategies) to work with your beliefs about what it will be like or what it means to keep a sleep log.

You may be wondering if you can continue using this book without completing a sleep log, given all the emphasis we are putting on this. On the one hand, we do not want to lose you “just” because you are not willing to track your sleep. On the other hand, the data you can collect in the sleep log will help you choose the treatment components that are most likely to help you, rather than the average person with insomnia. We have found the sleep log to be a very useful tool in about 98% of the people we have been able to help. We want you to benefit, too!

Should You Have an Overnight Sleep Study?

As we said in the introduction, this book is intended to help people with insomnia. You may think you have insomnia but actually have a different sleep problem, such as sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome (RLS), or periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD). These conditions need to be diagnosed and treated by a medical doctor. If you have not had an overnight sleep study, or have not had one recently, review this section to help you decide whether to prioritize being evaluated by a doctor.

The first clue that someone may have sleep apnea, RLS, or PLMD is excessive daytime sleepiness. You are “sleepy” if you feel as if you could fall asleep. When sleepy, you may yawn, feel as if your eyes are heavy or droopy, or find your head nodding. This is different from being tired, exhausted, or fatigued. Many of our clients say they are exhausted but not sleepy. In fact, they yearn to feel sleepy!

To determine if you are sleepy during the day, ask yourself how likely you are to fall asleep in various situations, such as being a passenger in a car, listening to a lecture, reading a book, sitting in a dark theater, or resting at home. If you are very likely to fall asleep in a number of situations, we would say that you are sleepy.

It is natural for you to be sleepy during the day if you are not getting enough good-quality sleep at night. The question is whether your poor sleep and daytime sleepiness are caused by insomnia or by another condition masquerading as insomnia. Here are additional questions that we ask our clients to screen for sleep apnea, RLS, and PLMD. Take a moment to answer these questions for yourself.

Apnea

|

Do you snore regularly (more than three times a week)? |

Yes |

No |

|

If yes, is your snoring loud enough to wake others? |

Yes |

No |

|

Does your snoring wake you up? |

Yes |

No |

|

Are you aware of waking up gasping for air? |

Yes |

No |

|

Has a bed partner seen you stop breathing or gasp for air during your sleep? |

Yes |

No |

|

Do you wake up multiple times a night? |

Yes |

No |

|

Do you often wake up uncomfortably warm, even though the room temperature “should” be comfortable? |

Yes |

No |

|

Are you overweight? |

Yes |

No |

|

Has anyone in your biological family been diagnosed with sleep apnea? |

Yes |

No |

We all have small pauses in our breathing while we sleep, but for most people these are very short and very infrequent. Someone with sleep apnea stops breathing for several seconds to several minutes, many times an hour. Most often people are not aware that they have stopped breathing, even if they wake up because of it. They may experience their sleep as restless, or say they have multiple awakenings throughout the night, or they may think they have slept solidly but feel unrefreshed in the morning. People with untreated sleep apnea usually feel very sleepy during the day.

If you are sleepy during the day and also answered yes to a number of the questions above, we strongly encourage you to consult with a doctor who is board certified in sleep medicine. He or she will ask a lot of the same questions and also will do a physical examination to determine if you should be evaluated for sleep apnea with an overnight sleep study. An overnight sleep study may be done in a sleep laboratory or in your own home using a portable device. If you do have sleep apnea, it is important to have it treated. Your doctor can help you find the best treatment for you (for example, a continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP] device, a dental device, or a positional device if you only have apnea when sleeping on your back). Many people with sleep apnea also have insomnia. Once your apnea is treated, if you are still having trouble with sleep, we hope you will return to this book.

Restless Legs Syndrome

|

When you are trying to relax or sleep, do you have an irresistible urge to move your body? |

Yes |

No |

|

When you do have an irresistible urge to move, does moving relieve discomfort or odd sensations (such as pain, aching in the muscles, or a “crawling” feeling)? |

Yes |

No |

|

Is the urge to move greatest at night, and least likely in the morning? |

Yes |

No |

RLS is a condition in which you have an irresistible urge to move, especially when trying to relax or sleep. The urge tends to be greatest at night and most mild in the morning, and is most often experienced in the legs. Moving usually makes you less uncomfortable. If you answered yes to the above questions, ask your physician to evaluate you to rule out other causes of RLS symptoms, such as vitamin deficiencies. Some people get full relief by correcting an iron deficiency, for example. If you have RLS, a medication may give you some relief.

Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep

|

Are your covers a mess, or twisted around you, when you wake up? |

Yes |

No |

|

Has a bed partner complained that you kick him or her while you are sleeping? |

Yes |

No |

Periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) are repetitive, involuntary movements, usually in the lower extremities. You may recognize these movements as brief muscle twitches, jerking movements, or an upward flexing of the feet. However, most people do not even realize they are having them. In PLMD, the PLMS occur about every twenty to forty seconds. They can cause you to have difficulty staying asleep or may just compromise the quality of your sleep, which results in excessive daytime sleepiness. PLMD is diagnosed with an overnight sleep study. Some medications can cause the disorder, and the disorder can be treated with other medications.

If you are sleepy during the day and suspect that you may have sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, or periodic limb movement disorder, please see a medical doctor for an evaluation. If, on the other hand, you are sleepy but answered no to the questions about these other conditions, your excessive daytime sleepiness may be caused by insomnia. It is reasonable to first try to treat your insomnia using this book. You can reconsider a sleep study if this treatment does not work for you, or if it helps you sleep longer but you still feel really sleepy during the day.

Do You Have a Circadian Rhythm Disorder?

In the next chapter you will learn about the relationship between your body clock (“circadian rhythm”) and the external clock, and how our bodies generally are able to keep these two clocks aligned so that we sleep at night and are alert during the day. Even for people with body clocks aligned in the traditional way, there are individual differences: you may be a “night owl,” a “morning lark,” or something in between. An extreme version of being a night owl is called delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS). An extreme version of being a morning lark is called advanced sleep phase syndrome (ASPS). In both of these conditions, the body clock and external clock are misaligned: you can get enough sleep that is of good quality, but only at a time that is out of sync with the environment and cultural norms. For example, people with DSPS may sleep well from 3 a.m. until 11 a.m. if given the chance, but life demands may necessitate a 7 a.m. rise time. In an attempt to get enough sleep, they are likely to go to bed much earlier than 3 a.m., even though their body is not yet primed for sleep. It is not surprising, then, that they may have trouble falling asleep. This is often mistaken for onset insomnia (difficulty sleeping at the beginning of the night).

Similarly, people with ASPS may sleep well from 8 p.m. until 4 a.m., but life demands or social norms may cause them to stay up much later. Because their bodies are primed for awakening at 4 a.m., they may wake up at this time even though they went to bed later. This is often mistaken for “terminal insomnia” (waking too early and being unable to go back to sleep). Take a moment to think about your own body clock. To answer the questions below, consider your experience on vacations or when you have been able to set your own schedule, as well as what time of day you feel most alert.

If the world revolved around your schedule, such that you could sleep any time your body wanted to and you would not miss out on life, what time would your body most want to sleep? (Indicate a.m./p.m.)

Bedtime Wake time

If you were able to keep this schedule every day without life interfering, do you think you would:

|

Get enough sleep? |

Yes |

No |

|

Get good-quality sleep? |

Yes |

No |

|

Feel rested upon awakening? |

Yes |

No |

|

Be alert during your waking hours? |

Yes |

No |

If your desired bedtime is before 9 p.m. or after 1 a.m., and you answered yes to the last four questions, you may have a circadian rhythm disorder. Some people who get properly diagnosed with one of these disorders decide to shift their lifestyle to accommodate their bodies’ natural rhythm. Others attempt to shift their rhythm to be more in sync with the external clock and the people around them. We will address phase-shifting strategies in appendix A. Because many people with circadian rhythm problems also develop insomnia, you may benefit from working through the rest of this book, too.

What Is Insomnia Costing You?

To be diagnosed with insomnia, your disturbed sleep has to cost you something. We call these costs “negative daytime consequences.” We are pretty confident that you have at least some negative consequences, because otherwise you would not be spending time reading this book! Still, we want you to pause and take stock. We will be asking you to take the same assessment at the end of this book, and knowing what has changed and what has stayed the same will help guide your next step. How does poor or unreliable sleep affect you during the day? How often? How much distress or impairment does this cause? Are you revolving your life around your sleep, so that you are living to sleep instead of sleeping to live?

Assessment 1.1: What Insomnia Is Costing Me

Think about how you feel and behave the day after a poor night’s sleep. Also think about the overall, cumulative effect of your ongoing sleep problems. Now look at the list that follows of common daytime consequences of insomnia.

Circle the number of days in a typical week you experience each consequence because of sleep disturbance.

For any items you scored 1 or more, rate how much this affects you:

0 = No big deal; I barely even noticed or thought about it until you asked.

1 = Mild impact/somewhat distressing.

2 = Moderate impact/quite distressing.

3 = Significant impact/extremely distressing.

For example, if you are late to work three times a week, this may not be a problem at all because you have lots of flexibility and you do not mind shifting your work hours (0); or it may cause some personal frustration but no real problems at work or with your after-work plans (1); or it may cause problems with your boss/coworkers/employees/clients, or with other activities because you have to make up the time (2); or it may get you fired or make you lose business (3).

|

Because of insomnia I… |

# Days in a Typical Week |

Impact(0–3) |

|||||||

|

…am late to work, school, or other activities. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…stay home from work or school, or cancel professional obligations. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…perform below expectations or am less productive. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…socialize less. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…exercise less. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…skip evening activities because I am too tired. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…skip evening activities because I am worried they will disrupt my sleep. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…have a harder time remembering things. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…have a harder time focusing or concentrating. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…am irritable with other people. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…am more sad, tearful, or anxious. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…worry about sleep during the day. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…feel anxious about how I will sleep that night. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…think about terrible things that may happen because of my insomnia (for example, impact on health, performance, relationships). |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…fall asleep at inopportune times (for example, during meetings or classes, or while watching movies). |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…am too tired to drive safely. |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

…feel physically uncomfortable (for example, burning eyes or headaches). |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

Your Next Step

In summary, if you have insomnia (trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, or unrefreshing sleep) that is interfering with your functioning or quality of life, and you do not have signs of sleep apnea, RLS, PLMD, or a circadian rhythm disorder, continue to collect data with your sleep log while you work through the next two chapters. We will help you review and make sense of your sleep log data in chapter 5.

If you have signs of apnea, RLS, or PLMD, your next step is to get evaluated by a physician who is board certified in sleep medicine. If you think you have a circadian rhythm disorder, jump to appendix A. Even if you have another sleep disorder and are successfully treated, you may find that you also have insomnia that can be treated with the program in this book.