Beneath the ground of Lake View Cemetery is some of Seattle’s richest history. Most Seattle pioneers are buried within Lake View Cemetery, which was the city’s major burial ground from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. Prominent Seattle pioneers include the Dennys, the Maynards, the Mercers, the Morans, and the Yeslers. Bruce Lee and Brandon Lee are also buried in this picturesque cemetery high atop Capitol Hill at 1554 Fifteenth Avenue East, just north of Volunteer Park.

Established in 1872 and purchased by the members of the St. John’s Lodge of the Order of Free Masonry, the land was bought from Doc Maynard. Before the burial sites at Lake View existed, in 1855 graves were dug east of Maynard’s Point or at the White Church, Seattle’s first church, or at the old Seattle Cemetery, located on the north side of the Denny Regrade. Many of the persons buried at those sites were dug up and reburied elsewhere and eventually ended up at their final resting place in Lake View.

Harry Watson of Bonney-Watson was sexton, and his partner Lyman Bonney was manager. Those two partners in life are now partners in death, buried toe to toe in this cemetery. For three recent generations, the Bladine family has managed Lake View Cemetery.

Memorial stones and markers of the past were made of slate and soft marble, with lengthy carved epitaphs. Many of the soft stones, although beautiful and easy to work with, have deteriorated in Northwest weather. Huge massive monuments and family plots were common for the times. Today’s graves are typically indicated by plain sandblasted granite headstones or markers, or a person is simply cremated.

In 1911, a site was dedicated “to the Memory of Confederate Veterans.” In 1926, a memorial was erected. In the northeast corner of the cemetery is the Nisei War Memorial Monument, dedicated in 1949 to Japanese American Veterans.

DEDICATION OF CHIEF SEATTLE STATUE. On November 13, 1912, Founders Day, a crowd gathers for the dedication of the Chief Seattle statue at Tilikum Place. Photographer F. H. Nowell took the historical photographs in downtown Seattle. Tilikum Place (tilikum means “welcome” or “greetings” in Chinook) is located at the corner of the original land claims of Denny, Boren, and Bell. Myrtle Loughery, the great-granddaughter of Chief Sealth, did the unveiling. Sealth stands on a pedestal wrapped in a stained copper shawl, with one arm raised in a symbolic greeting to the first white settlers, who landed at Alki Point in 1851. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives 30406, 30412.)

LAKE VIEW CEMETERY. Up at the top of Lake View Cemetery at the base of a giant Redwood Sequoia is a grey granite bench near the Whitebrook family graves. These words, inscribed on the bench, perfectly describe historic Lake View Cemetery: “East the mighty Cascades run free / North is the university / South, a great tree / West, lies the Sound / All these places were loved by me.”

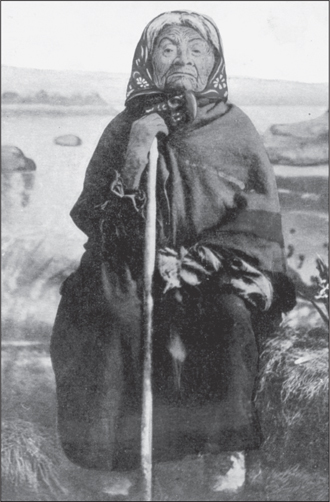

PRINCESS ANGELINE MEMORIAL. Angeline’s memorial reads as follows: “Born – 1811, Died – May 31, 1896. The daughter of Chief Sealth, for whom the city of Seattle is named, was a life long supporter of the white settlers. [Born Kakiisimla,] she was converted to Christianity and named by Mrs. D. S. Maynard. Princess Angeline befriended the pioneers during the Indian attack upon Seattle on January 26, 1856.” (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography.)

PRINCESS ANGELINE. A prominent Native American figure in Seattle’s history, her original name was Kakiisimla. Angeline lived her life on the shores of Puget Sound. She was married first to Chief Dokubkun and second to Chief Talisha, both from the Duwampish tribe. Angeline had two daughters. Mamie (Mary) married William Deshaw, and Chewatum (Betsy) married Bad Joe Foster. Angeline was also known as Kickisomlo-Cud but was renamed in 1852 to Princess Angeline by Catherine Maynard, who said, “You are far too handsome a woman to carry a name like that. I hereby christen you ‘Angeline.’ ” Wearing her famous red shawl, she was buried in a coffin that was shaped like a canoe. Angeline is said to haunt Pike Place Market, pictured below. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 10391.)

PRINCESS ANGELINE’S WATERFRONT PALACE. Angeline is pictured with her dog on the wooden portico of her house, built in 1881 on Pike Street. In her last days, her grandson Joe took care of her. While working as a washerwoman for the white settlers, she lived her last 10 years in an old shack built by Henry Yesler near Pike Place Market. Souvenir trinkets were sold with her photographs. (Courtesy of Seattle Public Library, No. 22898.)

ATKINS GRAVE SITE. Henry A. Atkins (1827–1885) arrived in Seattle in 1860. Along with two partners, he owned and operated a steam-driven pile driver that helped build docks and wharves up and down Puget Sound. (Circle K.)

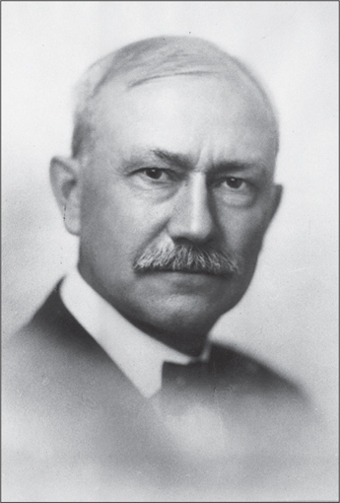

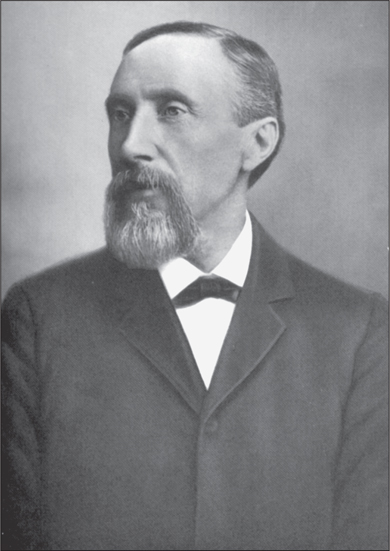

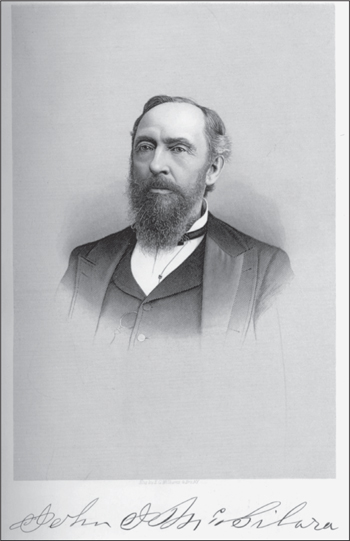

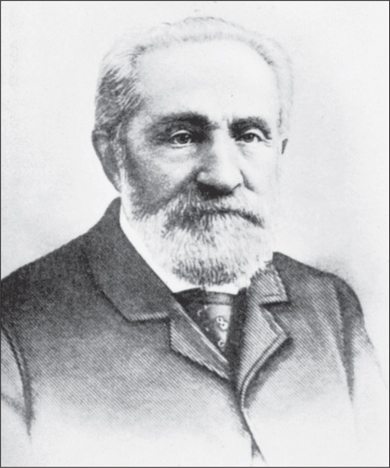

MAYOR HENRY A. ATKINS. Atkins, a Republican, was the first mayor of Seattle in 1865 when the city was incorporated the first time. In 1877, Henry Yesler brought suit against the city, saying there had been no right to incorporate a city in the territory. Seattle was unincorporated in 1877. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 12252.)

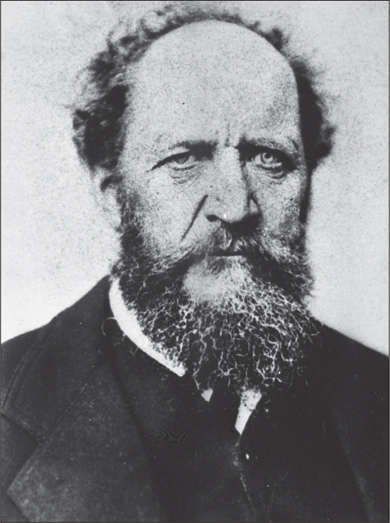

RICHARD ACHILLES BALLINGER MONUMENT. Ballinger (1858–1922) was born in Boonesboro, Iowa, and graduated in 1884 from Williams College. He was a lawyer and judge of the Superior Court of Washington in 1894. In 1904, he was elected mayor of Seattle. (Lot 31.)

RICHARD ACHILLES BALLINGER. In 1909, Ballinger was appointed secretary of the interior under Pres. William Taft. During that time, he was accused of having interfered with an investigation into the legality of private coal–land claims in Alaska. He was later exonerated. In March 1911, he resigned. The scandal helped to turn the election of 1912 against Taft, and it split the Republican party. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 12275.)

AUSTIN AMERICUS BELL MAUSOLEUM. The Bell Victorian Mausoleum had to be bricked over because of vandalism. Austin Americus Bell was born in Belltown to William and Sarah Bell. During the Battle of Seattle, the family’s house was burned to the ground and they fled to California. In 1875, the Bells returned to Seattle. In 1887, William Bell (senior) died from an unidentified and strange malady. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 540.)

AUSTIN A. BELL BUILDING. One day, Bell told his son about his dream to construct a building next to their Seattle residence. The next day, he died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. In 1889, Bell’s wife, Eva, built the Austin A. Bell Hotel using red bricks shipped in from San Francisco. It is located on First Avenue, a half-block north of Bell Street, adjacent to what is now the Belltown Pub. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 57720.)

LYMAN WALTER BONNEY GRAVE (1843–1922). Bonney was reported to be a good-natured fellow and was buried toe to toe with his partner Harry Watson. Bonney came from Iowa in 1852 across the Oregon Trail to Seattle. He bought into the undertaking business with Oliver Shorey. His daughters were the beautiful Bonney girls; one married Shorey, and another married druggist Gardner Kellogg. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 364.)

LYMAN WALTER BONNEY. Bonney was a member of the Bonney-Watson Company, funeral directors, and he spent most of his life on the Pacific coast. His undertaking establishment had the distinction of being the finest and best equipped in the United States. There was a modern crematory and columbarium, as well as a private ambulance service, all under one roof. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

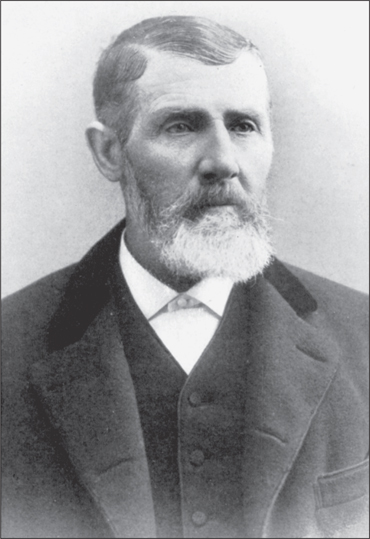

CARSON DOBBINS BOREN GRAVE (1824–1912). Behind the striking Denny plot is the plain grave site of Boren. In the summer of 1881, Boren and his wife, Mary, and daughter Gertrude traveled the Oregon Trail with the Denny-Boren party to arrive at Alki. After the winter, Boren, Denny, and Bell each laid claim to the 320 acres permitted to a married couple. Their claims were located across from Alki on Elliott Bay, which is now Seattle. (Lot 342.)

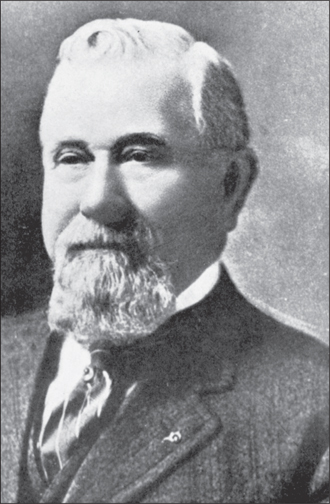

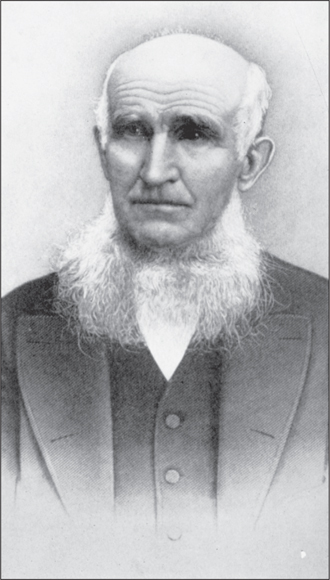

CARSON DOBBINS BOREN. Born in 1824 in Nashville, Tennessee, Boren brought with him to Seattle his building and hunting skills. Later he was named King County’s first sheriff to keep the peace between the Native Americans and the settlers. Around 1855, Boren, Charles Plummer, Dexter Horton, and others went on an expedition over Snoqualmie Falls Pass, searching for future railroad routes. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

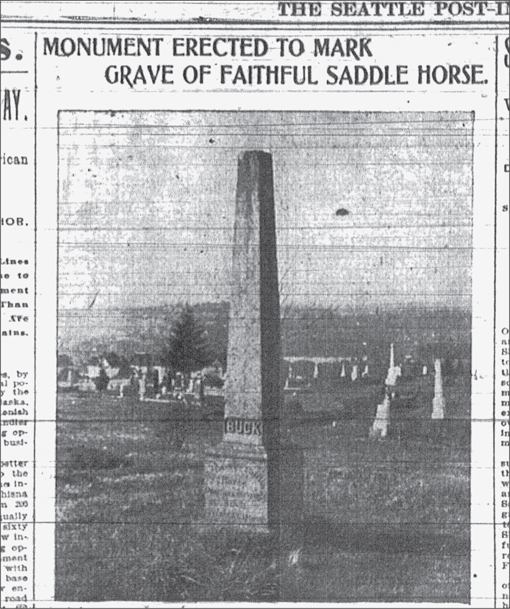

BUCK, FAITHFUL SADDLE HORSE MONUMENT. Buck was buried at Lake View Cemetery. Buck’s owner, Irving Wadleigh, who erected the monument, was well known among Seattle’s pioneers. A March 31, 1901, a newspaper article reported the following: “On one of the highest spots in Lake View Cemetery stands the granite shaft which is shown in the accompanying half-tone cut. It was erected by a grateful man to mark the resting place of a true friend.” Engraved on the monument was, “BUCK, My Favorite Cattle Horse, Died September 20th, 1884 Aged 18 Years and 6 Months.” Engraved on the eastern side of the monument is this inscription: “For 13 years my trusty companion in blackness of night, in storm, sunshine and danger.” On the north side were the words, “Corniced In Adversity Faithful.” Wadleigh and Buck were constant companions for 12 years at his cattle ranch in Eastern Washington. Buck was later removed from Lake View Cemetery. (Courtesy Seattle Post-Intelligencer.)

CARR MONUMENT. Ossian Carr (1832–1912) and his wife came to Seattle in 1852. For the Territorial University, Carr carved the fluted Ionic columns that currently stand at the University of Washington. In 1862, when the Territory University first opened, Mrs. Carr taught elementary school. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 420.)

BUTLER HOTEL. Hillory Butler built the Butler Hotel, located in Pioneer Square. This photograph shows the hotel on December 13, 1920, with the Butler block visible. Hotel Butler was considered the city’s classiest hotel through the 1890s. In 1860, Butler worked with the Grand Lodge of Free Masons and started a Seattle chapter. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 47329.)

HILLORY AND CATHARINE BUTLER MONUMENT. A granite obelisk overlooks one of the best sites at Lake View Cemetery. Butler was born in Virginia. He journeyed across the Oregon Trail and arrived with the Bethel Party in 1853. During the Native American unrest of 1855–1856 Butler would race to the safety of Fort Decatur on Cherry Street and once ran in wearing his wife’s red petticoat. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 147.)

JAMES COLMAN AND FAMILY MARKERS (1832–1906). Gravestones made of red granite cover the Colman family in this plot. Pier 52 is a well-known tourist area in Seattle and used to be named the Colman Dock. James Colman is also known for building the Colman building on First Avenue. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 459.)

JAMES COLMAN. In 1861, Coleman arrived in Seattle and bought William Renton’s sawmill in Port Orchard. Leasing Henry Yesler’s sawmill in 1872, he turned it into a 24-hour operation. He helped with finishing the Seattle and Walla Walla Railroad. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

VOLUNTEER PARK. Pictured May 1, 1900, Seattle City Council members are having lunch on an official inspection tour in Volunteer Park. Colman sold 40 acres of land to Seattle for $2,000. In 1885, this land was used as a cemetery named Washelli. In 1893, the graves were removed and the land was designated as Lake View Park. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 7337.)

FRYE MONUMENT. Buried below this monument are Charles Frye; his wife, Catherine; their children, including Roberta Frye Watt, who wrote The Story of Seattle, and Sophie Frye Bass, who wrote Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle; George Fortson; and Virgil Bogue. Fortson and Bogue married into the family. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 422.)

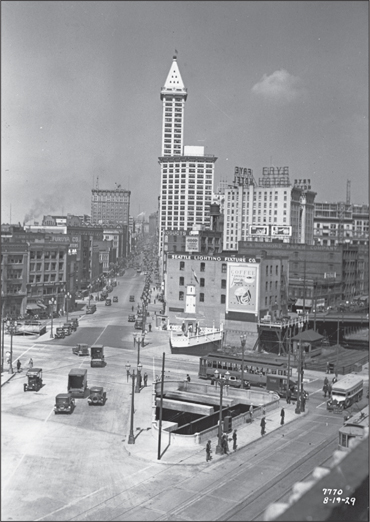

FRYE HOTEL. This photograph, taken August 19, 1929, is from Second Avenue South on the bridge at Jackson, facing the Frye Hotel. The hotel was 11 stories tall. Frye was also known for the Frye Opera House and Frye Museum on Seattle’s First Hill. The opera house burned down in the great Seattle fire of 1889, so Frye built the Stevens Hotel. With A. A. Denny, he built the Northern Hotel. He also built the Barker Hotel. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 3587.)

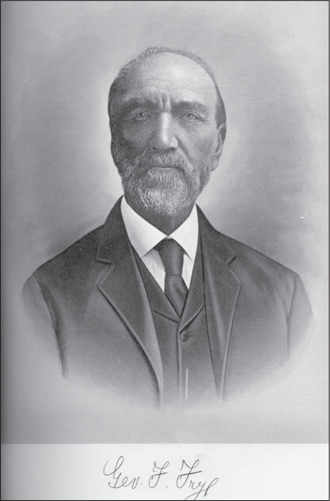

GEORGE FREDRICK FRYE (1833–1912). Frye crossed the continent in 1852 with an ox team, arriving in Seattle in 1853. His first job was as a sawyer at Yesler’s mill. He established the first meat market in the city and was associated with Arthur Denny and Henry Yesler in building the first sawmill and the first gristmill in the city. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

LOUISA CATHERINE DENNY FRYE (1844–1924). Louisa Frye, besides being the mother of their six children, was by her husband’s side in every enterprise that he undertook and was the inspiration for much of what he accomplished. They were always together, she driving about with him from building to building and he consulting her on every decision. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

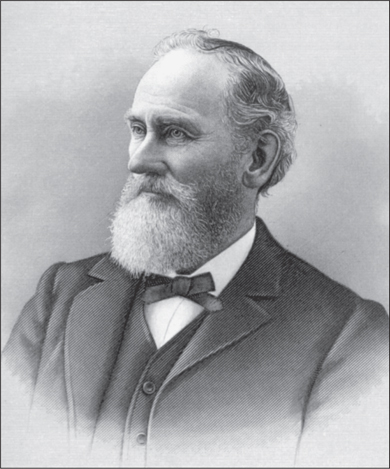

ARTHUR ARMSTRONG DENNY (1822–1899). On April 10, 1851, Denny left Cherry Grove, Illinois, and traveled for 108 days on the Oregon Trail. On November 4, 1851, the Denny party arrived on the schooner Exact at Alki (West Seattle). Denny was a Christian, a lifelong teetotaler and political conservative, and achieved most of his wealth from real estate. Asked to sell his land, Denny replied, “But what would I do with my cow?” (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

MARY BOREN DENNY (1822–1910). In 1843, Arthur Denny married Mary Ann Boren in Illinois. She was the mother of his children and was the brave, staunch comrade of all his high endeavors. He attributed much of his courage through the hard years of pioneering to her uncomplaining companionship. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

DENNY FAMILY MONUMENTS. Buried at Lake View are at least four generations of Dennys. Overlooking Seattle, this plot is one of the most spectacular, with a black and white checkered marble walkway leading up to a granite column. The individual markers are in pink granite with carved gilt lettering. The Dennys are also credited with the founding of Seattle. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 342.)

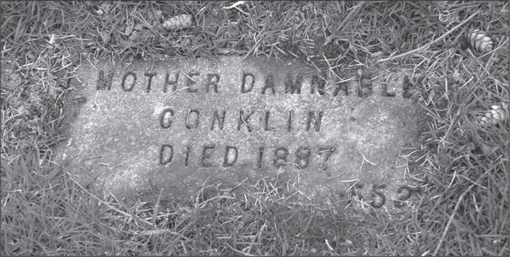

MARY ANN BOYER CONKLIN GRAVE SITE. Conklin (1821–1873) was better known as “Madame Damnable.” She ran a brothel upstairs at the Felker house and was known for her scrumptious cuisine and blasphemous tongue. Conklin’s first grave site was at the old Seattle Cemetery. She was buried next at the first Washelli Cemetery and then, lastly, at Lake View Cemetery. When they reburied her, they discovered that she was smiling and that her bones had turned to 1,300 pounds of stone. O. C. Shorey, the town’s undertaker, points out that the gravestone incorrectly identifies the year of her death as 1887. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 552.)

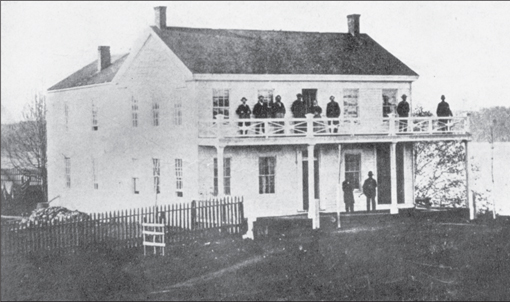

FELKER HOUSE. Capt. Leonard Felker brought the house around the Horn in his ship Franklin Adams as a complete “house kit.” It was assembled at Jackson Street and First Avenue South. Upstairs of the Southern-style mansion, Madame Damnable ran her whorehouse. After the Indian War, the city wanted to burn the brush down around the building so they could see any attackers approaching, but Damnable kept the authorities at bay with her mouth and a few mean dogs. If the brush were gone around the Felker house, passersby would be able to see her customers. She eventually gave in. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

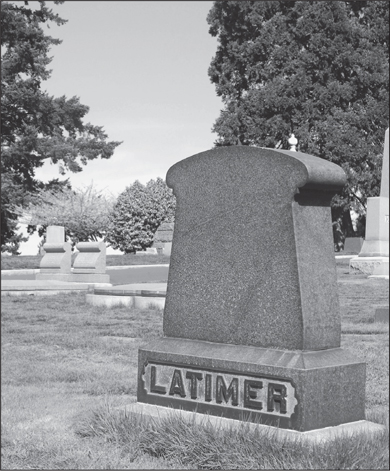

WILLIAM GUTHRIE LATIMER MONUMENT. This monument is made of black granite. Latimer was born in Tennessee and, in the spring of 1850, might have been the first white person to cross Snoqualmie Pass. It was rumored that, in the summer of 1850, he built a small hut at what is now Second Avenue and Columbia Street in downtown Seattle. In the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, however, he stated he had not come to Puget Sound until the fall of 1852. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 165.)

MOSES AND SUSIE MADDOCKS GRAVE SITES. Pink granite slabs cover the graves of Moses and Susie Maddocks. Moses Maddocks (1833–1919) built a grand establishment called the Occidental Hotel in 1874. He also owned a drugstore on Front Street (now First Avenue). A second Occidental Hotel was built where the first stood and was burned to the ground in the great Seattle fire of June 6, 1889. It was rebuilt again but torn down in the 1960s, and in its place was built a garage. This garage is known as the “Sinking Ship Garage” and can be seen in Seattle today at the corners of James Street, Second Avenue, and Yesler Way. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 178.)

ELISHA P. FERRY (1825–1895). Ferry, a Republican, was a lawyer from Illinois. In 1869, Pres. Ulysses Grant appointed him surveyor general and he moved to Washington Territory. In 1872, Grant appointed him governor for eight years. After Washington became a state, Ferry became its first elected governor in 1889. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley, History of Seattle.)

JOHN LEARY (1837–1905). A partner of Elisha Ferry, Leary arrived in Seattle in 1869 with an unusual aptitude for business and a genius for the successful creation and management of large enterprises. On July 14, 1884, voters elected the businessman as mayor of Seattle. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 12264.)

LEARY AND FERRY MONUMENT. Partners John Leary and Elisha P. Ferry are buried beside this cross. The Leary family is buried on the left of the cross, and the Ferry family plots are to the right. Not only were the two men business partners, but Leary married Ferry’s oldest daughter, Eliza. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Circle EE.)

HORTON FAMILY MONUMENT. This gigantic gray granite Egyptian obelisk with a surrounding pedestal marks the burial site of Dexter Horton (1825–1904) and his wives Hannah Shroudy, Caroline E. Parsons, and Arabella C. Agard. Horton grew up in Illinois and, in 1853, crossed the Oregon Trail with the Bethel party. On a gloomy day in April 1853, Horton arrived in Seattle, broke and recovering from the “ague.” (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 181.)

DEXTER HORTON. His first job was working to remove stumps from Bell Town for $2.50 a day. That fall, he and his wife managed the cookhouse of Renton’s sawmill in Port Orchard. Returning to Seattle, he next worked at Yesler’s Sawmill while his first wife, Hannah, worked at the Yesler cookhouse. They saved every penny that they could and stored it in their old wooden steamer trunk. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

DEXTER HORTON BUILDING. This October 1928 photograph was taken outside of the Dexter Horton Building. In 1854, Horton owned a general store on Commercial Street (now First Avenue) with Arthur Denny and David Phillips. Horton was Seattle’s first banker. Rugged loggers and seaward sailors would ask trustworthy Horton to store their money. Horton put their gold coins in a bag, tied it with their name around it, and shoved it into a coffee barrel or hid it in a safe place in the store. When the depositors returned to make a withdrawal or deposit, Horton would fish around the barrel or pull it out of its safe hiding place to complete their requested transaction, then rewrite the balance. As a result, much of the currency and coins of the day smelled like coffee. The banking business was taking off in Seattle; with $50,000 invested, the Horton and Phillips Bank was begun. The bank went through transition and several name changes, first as Seattle First National Bank, then Seafirst Bank, and now Bank of America. Horton, who is the essence of a rags-to-riches pioneer, died on July 28, 1904, in his Seattle home. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 3159.)

KINNEAR FAMILY MONUMENT. This Victorian monument with three rises represents the Christian tenets of faith, hope, and charity. A partially draped urn sits at the top of this grey granite column. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 169.)

GEORGE KINNEAR. Kinnear (1836–1912) served during the Civil War. Every month, he sent his pay to his mother, who saved it and gave it to him upon his return. Kinnear bought land on Queen Anne Hill in 1874. He helped build the wagon road through Snoqualmie Pass and organized the city’s immigration board. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

KINNEAR PARK. Taken in May 1, 1900, this image shows the Seattle City Council inspection tour on Kinnear Park lawn. For the price of $1, Kinnear sold to the city this wooded piece of land that later came to be known as Kinnear Park. Sherwood Park History files state in an Olmsted report, “Band concerts were given each Tuesday evening in the pavilion during the 1910 season and proved a boon to the [residents], the average attendance was 2690.” On Sunday afternoons in 1910, and again in 1936, community meetings were held on the lawn. In 1903, an Olmsted report approved the park’s development but pushed for more individuality. The 1904 report mentioned the popular lower areas for picnickers. In 1909, the report noted the presence of “swings, teeters, sand courts, etc.,” for small children. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 7304.)

DAVID AND CATHERINE MAYNARD GRAVE SITES. At the base of a giant sequoia redwood tree are the flat gravestones of the Maynards. Thomas Prosch planted the giant redwood tree at Lake View’s highest point. Dr. Maynard came over on the Oregon Trail, and during his journey he met his soon-to-be second wife, Catherine. Her epitaph reads, “She did what she could.” (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 211.)

DR. DAVID SWINSON MAYNARD (1808–1873). Maynard arrived in Seattle in 1852. His innovative strategy to sell salted salmon to San Francisco failed, so he started Seattle’s first store, which sold general merchandise and medicine on Main Street and First Avenue. He also served as Seattle’s justice of the peace and was responsible for suggesting the name Seattle, after his new Native American friend Chief Sealth. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

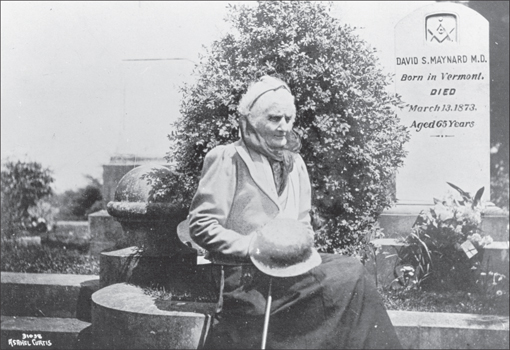

CATHERINE MAYNARD AT DOC MAYNARD’S GRAVE SITE. This famous 1906 photograph of Catherine Maynard (1816–1906) was taken by Asahel Curtis at Lake View Cemetery beside Doc Maynard’s grave. Catherine risked her life to warn the settlers in Seattle of an imminent attack by Native Americans on January 25, 1856. Catherine met Doc Maynard on the Oregon Trail after her husband and several in her family died. Believing that Maynard had officially divorced his first wife, Catherine married him in 1853. In 1872, Lydia Maynard, the first wife, showed up to claim half of Doc’s land. Maynard had declared his first wife dead in order to marry his second wife. Lydia lived with Doc and Catherine while she was claiming ownership of half of the original land deed, a situation that had the town raising eyebrows. (Courtesy Museum of History and Industry, No. 2741.)

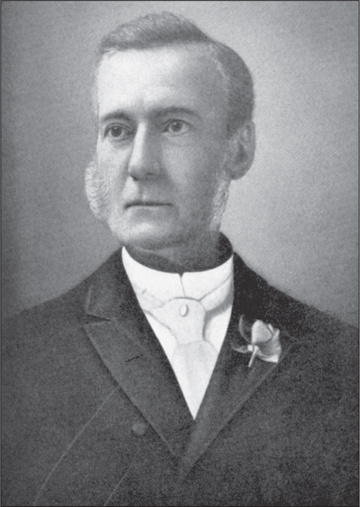

JUDGE JOHN J. MCGILVRA (1827–1903). In 1864, McGilvra was appointed by Abraham Lincoln as the U.S. attorney for the Territory of Washington. He arrived in Seattle in 1867 and built a nice white house, Laurel Shade, on the shores of Lake Washington. The house was later used by the Pioneer Historical Society. (Lot 416.)

JUDGE JOHN J. MCGILVRA. Before McGilvra came to Seattle, he practiced law in Illinois in association with Abraham Lincoln. In the 1860s, McGilvra purchased 420 acres of land for $5 an acre on the shores of Lake Washington. At the time, land was being sold to help finance the University of Washington. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

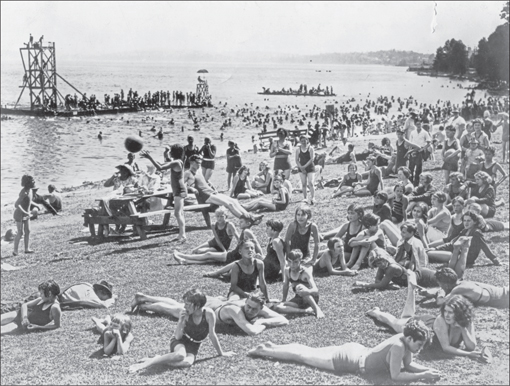

MADISON PARK. This 1930 photograph shows Madison Park, one of five Lake Washington bathing beaches. Judge John J. McGilvra created this lakeshore park, which became the most popular beach in Seattle during the late 19th century. It featured floating bandstands, a paddle wheel steamboat, a boardwalk, beer and gambling halls, athletic fields, a greenhouse, and piers for ships that cruised on Lake Washington. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 29786.)

MERCER MONUMENT (1813–1898). Thomas Mercer arrived in Seattle in 1852 and made a land claim on the southwest shore of Lake Union. He had five daughters who married into pioneer families. His brother Asa was responsible for bringing in potential brides called the Mercer Girls. He held a huge Independence Day picnic in 1854 at his farm and was responsible for naming Lake Washington after the first president and Lake Union. Mercer’s Island (Mercer Island) was named after him. He loved to have natives bring him to the island in a canoe so he could explore and pick berries. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 292.)

THOMAS MERCER. Mercer was born in Harrison County, Ohio, in 1813. He crossed the Oregon Trail with his wife and daughters. Mrs. Mercer took ill and died when the family reached the Cascade Mountains. Mercer Street is the dividing line between the land he claimed and the Denny claim. In 1859, he went to Oregon for the summer and married Hester L. Ward. During the Indian War, Mercer’s house was spared from being burned because, “Oh, old Mercer might want it again.” (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

MEYDENBAUER FAMILY MONUMENT. This unpretentious monument marks the grave site of one of Bellevue’s foremost landowners. William Meydenbauer (1832–1906) is well known for Lake Washington’s Meydenbauer Bay and Meydenbauer Park. He was also the third owner of Eureka Bakery in 1871. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 218.)

OSBORNE MONUMENT (1834–1881). Under a huge column of Carrara marble that dissolves in the Pacific Northwest dampness lies James Osborne, who was proprietor of the famous Gem Saloon. Because of its wild reputation, the establishment was given the title “Sin City” on Puget Sound. He willed his estate to the City of Seattle for the construction of an opera house, which was later named the Seattle Opera House. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 197.)

MORAN FAMILY MONUMENT AND PLOT. This very impressive monument was designed by Moran and built out of riveted sheets of bronze welded together to resemble a ship’s hull. The Morans got their wealth from shipbuilding. This Egyptian obelisk sits on huge plots (lots 1147–1149) and is the largest family site at Lake View Cemetery. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography.)

MORAN BROTHERS WITH FAMILY. The Moran brothers pose around 1903 with their wives and children on Sunday after church at the shipyards. Moran Brothers Company meetings at the shipyard often were a family affair. The family corporation kept all of their stock within the family. (Courtesy Rosario Resort.)

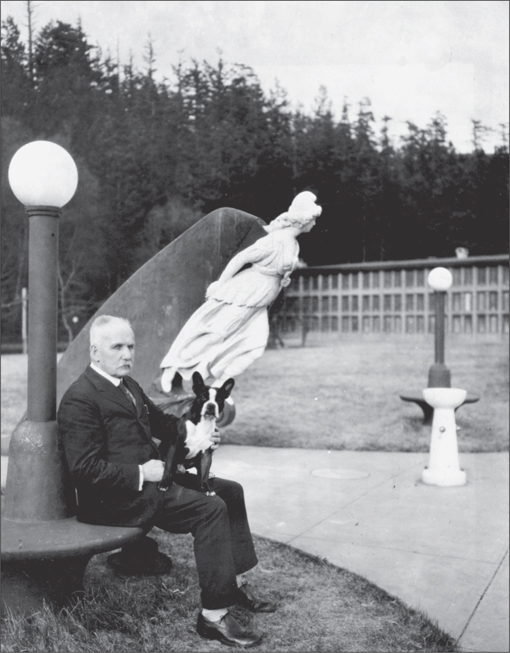

ROBERT MORAN WITH KENO. Robert Moran (1857–1943) was born in New York City, the grandson of an Irish immigrant who came to America in 1826. In November 1875, at the age of 17 years, he was on a steerage ticket and landed at Yesler Dock. Upon arriving, he charged his first breakfast at a local hash house. In a July 4, 1937, letter to the Seattle Times, he wrote, “Thirty-one years ago I left the shipbuilding business in Seattle. I was a nervous wreck. The doctors had me ticketed for Lake View Cemetery—due, as they said then, to organic heart disease. Doctors in those days were not as well informed as they are now on the ills of the human body.” (Courtesy Rosario Resort.)

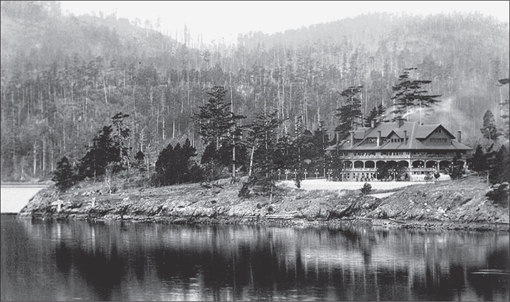

ROSARIO RESORT. Previously called the Moran Mansion, the Rosario Resort, in the San Juans, has five floors and a total of 54 rooms, including 18 bedrooms. Moran designed and built the maroon mansion and his own direct-current hydroelectric power system. An indoor saltwater swimming pool and recreation room—including a pool table, billiard table, and a two-lane bowling alley—were located on the 6,600-square-foot lower level on floors made of Italian mosaic tile. At 7:00 a.m. sharp in the music room balcony, Moran would wake the house playing the pipe organ. One of his favorite songs was “Work, for the Night is Coming.” The mansion, including all of the furnishings and outbuildings on 1,338 acres, was sold in 1938 to a Californian named Donald Rheem for $50,000. Rheem’s wife was quite a character and played poker with the boys in town while wearing a flaming red nightgown. After the game, she would jump on her motorcycle and ride back to the mansion. Her ghost still makes an appearance at Rosario Resort. (Courtesy Rosario Resort.)

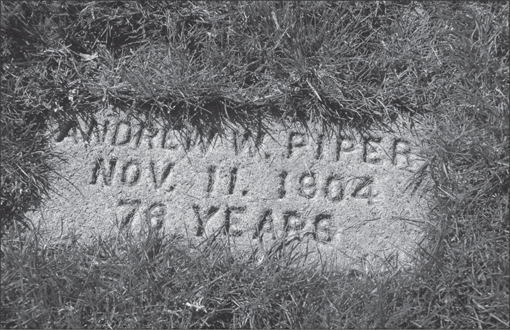

PIPER GRAVE. Andrew W. Piper (1828–1904), who was famous locally for “Piper’s Dream Cakes,” took his recipe to the grave. The U.S. government took Piper’s property on Lake Washington for the Sand Point Naval Station. In return, they gave him land north of Shilshole, which is now Carkeek Park. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 184.)

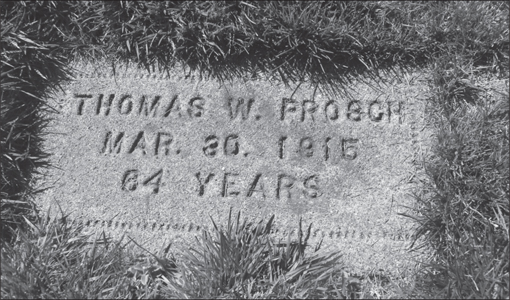

PROSCH MARKER. Thomas Prosch (1850–1915) was a prominent Seattle historian. His father, Charles Prosch, was editor of the Puget Sound Herald and wrote about the lack of wives for Seattle’s primarily male population. The Mercer Girls were imported as a direct result of his editorial. In 1885, Prosch became editor of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. He wrote several autobiographies and a detailed history of Seattle. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 164.)

CHARLES PLUMMER (1822–1866). Plummer was buried with Masonic honors. The city’s flags were half-masted, and many of the houses were draped in mourning. He ranked with Yesler, Terry, and Maynard in the early development of Seattle and its resources. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 360.)

STORE OF PLUMMER AND HINDS. Taken in 1860, this photograph shows Plummer’s store at First Avenue South and Main Street. Plummer’s name is linked with all of its early advancement. His store was one of the largest; he had his own wharf and independent waterworks to supply it with water. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

PONTIUS FAMILY GRAVES. In a roundabout way, Rezin W. Pontius built Seattle into what it is today. Seattle in the 1880s was built almost entirely out of wood, including the timber-planked streets. After the fire, Arthur Denny and Doc Maynard’s contradictory street plats could at once be redesigned. With the streets raised, the city’s sewers did not drain backwards with the tides as they previously did. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 175.)

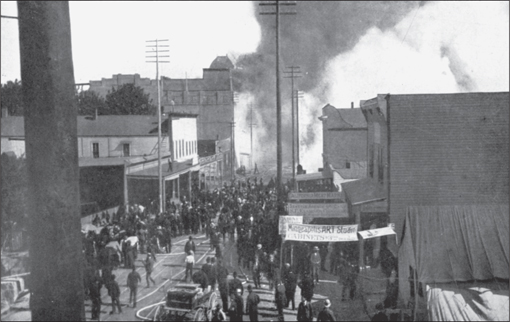

GREAT SEATTLE FIRE. Taken on June 6, 1889, this photograph shows the beginning of the great Seattle fire, which was caused by an overturned glue pot in the basement of the Pontius Building. All the buildings south of Spring Street and west of Third Avenue were burned to the ground in one day, giving way to a brand new beginning. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

HARRY WATSON GRAVE SITE (1871–1915). Watson’s grave is a solid grey granite slab that rests on four bronze lion’s feet. At Watson’s feet is buried his partner Lyman Bonney. Eventually the undertaking business of Shorey and Bonney was sold completely to Bonney, who became partners with Watson to form the Bonney-Watson Company. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography.)

SHOREY FAMILY BURIAL PLOT. This massive granite stele of pre-Christian Rome marks the Shorey family plot. Oliver C. Shorey (1831–1900) was respected and honored in the community, and the sterling worth of his character was attested to by all with whom he came in contact. He married Mary Bonney in 1860, and the next year he carved Doric capitals on the soon-to-be university that the Reverend Bagley had notoriously schemed to build, even though there were no students to attend. With the earnings, Shorey opened a cabinet shop at the corner of Cherry Street and Third Avenue. There he made cabinets, furniture, steering wheels for steamboats, billiard tables, and other similar pieces. At that time, it was customary for the cabinetmakers to also build coffins. He eventually started the first undertaking business in Seattle, called O. C. Shorey Undertaking Company. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Circle M.)

TERRY MONUMENT. Charles C. Terry (1830–1866), Mary Russell Terry, and their family were reburied beneath a 10-foot-tall white Carrara marble obelisk. Charles was recognized as one of the most honorable men and valued citizens that Seattle had ever known. At one time, Terry owned all of New York Alki (in Chinook, “by and by” or “in the future”). In 1855, Terry bought half of Carson Boren’s land for $500 and traded his loyalty to Seattle. After the Native American attack of 1857, he traded his settlement for 320 acres from Doc Maynard. At that time, he was Seattle’s largest land baron. In 1856, he bought the Bettman Brothers General Store and opened the Eureka Bakery, which made several pioneers rich, such as Meydenbauer. Tuberculosis killed him at a young 36 years. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 322.)

HENRY AND SARA YESLER MONUMENT. The Yesler monument was a stock mail-order item and was intended to overlook Henry (1807–1892) and his two wives. Sara Yesler is buried here, but Yesler’s second wife, Minnie Gagle (who was also his second cousin), declined to be buried there. The third grave site is empty. (Courtesy Cherian Thomas Photography, Lot 111.)

HENRY YESLER (1807–1892). Yesler was Seattle’s first millionaire. In October 1852, he arrived in Seattle and built a steam-powered sawmill on Elliott Bay. This sawmill was built at the end of Mill Road (now Yesler Way), famously known as Skid Road for the way the logs skidded down the steep hillside. He also owned Yesler’s Cookhouse, Yesler’s Wharf, and built the city’s first water system. The King County Courthouse now occupies the spot where his once-great mansion stood before it was burned down in the great Seattle fire. (Courtesy Clarence Bagley.)

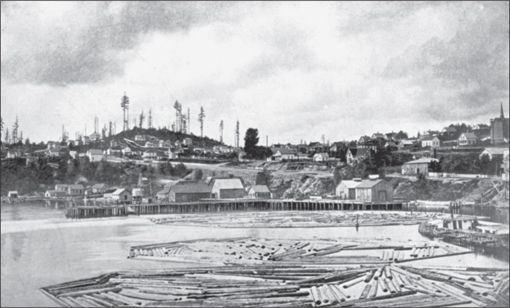

HENRY YESLER’S WHARF. This c. 1885 photograph shows that Yesler’s Wharf was the site of Seattle’s first steam-powered sawmill, built by Yesler in 1852. The machinery arrived from San Francisco before it had a roofed area to cover it. The mill began cutting lumber in March 1853, with a crew composed of Native Americans and white men, many of the latter during the later years rising to positions of wealth and influence in the affairs of the city and state. George F. Frye was the head sawyer. (Courtesy of Clarence Bagley.)

LOU GRAHAM MARKER (1860–1903). Dorothea Georgine Emile Ohben, whose stage name was Lou Graham, arrived in Seattle in 1888 on the steamer Pacific Pride. She bought and operated a parlor house (whorehouse) on Third Avenue and Washington Street. It was just down from city hall and was reputed to be frequented by Seattle’s elite. She made a fortune and invested in real estate, only to die at the age of 42 from syphilis. Purportedly she left her riches to family in Germany, not to King County Public Schools. Graham is buried in a less prominent section chosen by her executor; away from her clientele on the hill. (Lot 926.)

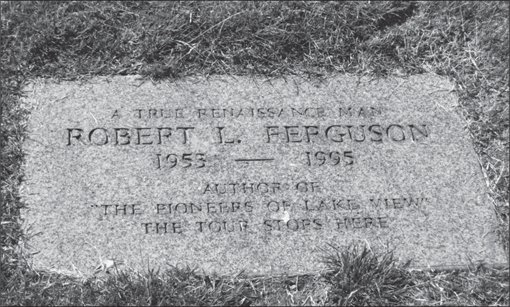

ROBERT L. FERGUSON (1953–1995). Ferguson’s epitaph states, “The Tour Stops Here.” He wrote The Pioneers of Lake View: A Guide to Seattle’s Early Settlers and Their Cemetery, printed in 1995. The book is not about dead people and death so much as it is about life and how our pioneers of the Northwest lived it. The last entry in his book is the grave of the infamous Lou Graham. His grave is next to hers now, making it the last stop on the tour.

UNDEVELOPED LAND, NORTH TRUNK HIGHWAY. Mount Rainier was clearly visible from the west side of the once-dirt North Trunk Highway (now called Aurora Avenue) in 1921. Before the Aurora Bridge existed, this undeveloped property was supposed to be a housing development, but no one wanted to drive his or her automobile such a long way from Seattle. (Courtesy Evergreen-Washelli Cemetery.)

DEDICATION OF EVERGREEN CEMETERY, C. 1922. A huge gathering at Evergreen Cemetery is pictured around 1922. Note that the dirt road that was once on undeveloped land on the North Trunk Highway is now the populated Aurora Avenue. (Courtesy Evergreen-Washelli Cemetery.)