The living room has been pronounced dead—again. Cause of death: asphyxiation by fabric, furniture, and disuse. Born around 1910 from a venerable line of drawing rooms and parlors, the living room has been survived by the family room, great room, retreat, patio, and SUV. In lieu of flowers, the house asks that you observe a moment of silence on a sofa at your nearest Starbucks.

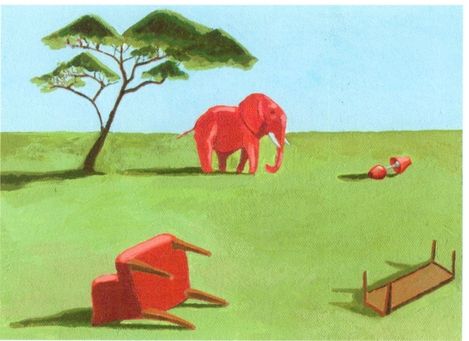

Every generation proclaims the death of the living room, yet it keeps coming back. We seem to need its empty formality, choosing to preserve a bit of protected, cultivated parkland in the urban centers of our busy houses. The living room is an elephant in the modern dwelling—a large room, often the first one you see, flaunting the home’s most cherished furnishings, yet largely ignored in daily life. In order to protect the living room from the slow, terrible death caused by toy infestation and piles of junk mail, home owners and developers have quarantined it with garage room entryways, family room duplications, and sunken designs that isolate it from regular traffic. Periodically, domestic writers (joined by the occasional husband) pronounce the demise of the living room, decrying it as wasted space and conspicuous consumption. Yet these elephants keep butting back into our floor plans. The living room expresses people’s desire to mark off a space that is casual enough to afford comfort, formal enough to invite self-expression, and austere enough to resist unwanted clutter.

The mother of the living room is the parlor, which enjoyed its heyday in the Victorian era. The nineteenth-century parlor sat at the front of the house, but in its own cage, safely hidden behind a door just off the entrance hall. Wrapped in factory fabrics and stuffed with collectibles, the parlor was a museum of memories. The parlor concept quickly spread to the apartments, balconies, and even tents of working people, thanks to the furniture ensemble known as the parlor suite, a sitting area grouped around a small table. The sofa still performs this parlorizing function today, popping up in waiting rooms, cafés, and offices as a symbol of domestic comfort and hospitality.

Between 1900 and 1930, the word “living room” replaced “parlor.” Along with the new name came a more open floor plan inspired by the modernism of the Arts and Crafts movement. Yet formality crept back in, and the living room soon froze once more into a precious precinct of order. Beginning in the 1950s, the family room and the great room emerged as warmer alternatives, and for a while, the living room seemed to be going extinct, forced out of the domestic ecosystem by these more relaxed and resilient spaces.

But the open plan of the family room or great hall breeds its own dangers. With everything from cooking and eating to homework and home offices happening in one sprawling area, heaps of paper and baskets of toys build up quickly. The messiness of the open plan in turn elicits the home dweller’s desire to restore a pocket of order.

And so the living room keeps returning. My own living room, which vaunts a cathedral ceiling and a bank of double-height windows, is the only architectural gesture in our southern California tract house. We’ve reduced the furniture to two modern benches, a side board, and a bank of CDS. It functions more as a foyer than a sitting room, but we enter its well-lit space every day, through the front door. Its austerity may discourage immediate use, but the very emptiness of the room performs a mental function for the whole house. It is a physical embodiment of repose amidst the whirl of daily activity. Our living room, I’ve decided, is like a sleeping cat, whose idle purring inserts a quiet rhythm into the busy biology of the household. Like our cats, our living room sustains us simply by doing nothing at all. JL

LIVING ROOM Elephant in the house

The living room is a public space, not a private one. It’s an area where people gather, perhaps every day on an informal basis, or—in more rigid and spacious houses—only on holidays, funerals, and in-law visitations. Many things go on in modern living rooms, including reading, snacking, watching television, listening to music, and drinking large or small quantities of alcohol.

The activity that has traditionally defined the living room is conversation. The choice and placement of furniture, the character of the lighting, and the overall sound, color, and ambience are all designed to get people talking. Sofas and chairs are angled and spaced to keep bodies close, but not uncomfortably so. Flat surfaces permit the display of objects as well as the serving of snacks. Shelves of books absorb sound (so that you can hear the person next to you); they also offer a ready reserve of conversation topics. Fireplaces provide a visual focal point as well as an expression of warmth (even if the real heat is coming from a radiator or from thy neighbor’s thigh). Today, many households are apt to replace their fireplace with a large-scale TV set, while orienting their furniture more for viewing than for talking—but even television is more fun when watched with other people.

Interior designers advocate three kinds of lighting for most rooms: general illumination, typically reflected off the walls or ceiling; task lighting for reading, knitting, or making paperclip chains; and accent lighting for showing off works of art. A room equipped only with general illumination will feel dull and flat, whereas a room lit only with lamps will be dark overall, punctuated by stingy dabs of brightness. Local lighting provides sparkle and contrast within a generally lit room. EL

FUNCTIONAL FURNITURE GROUPING

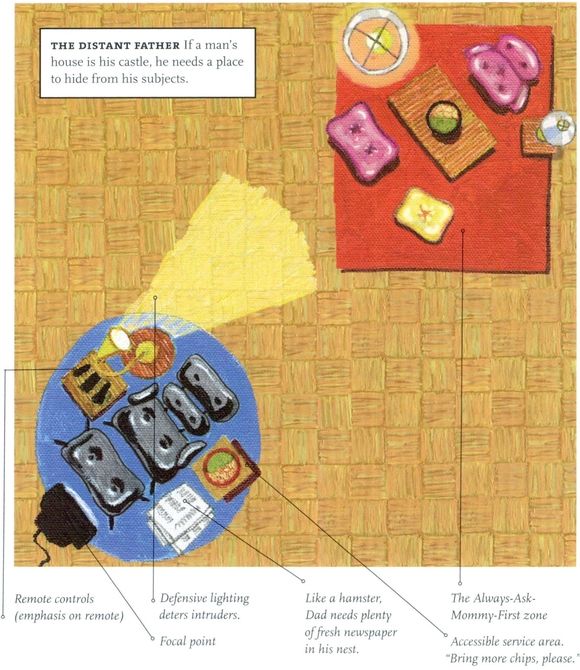

Interior designers and feng shui enthusiasts have generated a wealth of guidance about how to arrange furniture to achieve social harmony and inner peace. But what about households who would rather be miserable—or who gather together only under threat of punishment?

INSIDE OR OUTSIDE? The Dutch designer Petra Blaisse created this yellow silk curtain to hang inside an exhibition (designed by Rem Koolhaas/OMA at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 1989). The curtain is blown by artificial wind, producing an exquisite illusion of contact with the outside world.