I live on a cul-de-sac in Southern California. Built in 1989, the facades on our street are swallowed up by the great beige blankness of garage doors. When my children were very young, the neighbors and I would sit at the shadeless edges of our driveways wearily watching our toddlers play in the asphalt circle. A porch retreat would have been welcome (a baby sitter even more so).

On an adjacent street, built just a few years later, the porch is back, part of the New Urbanism, a movement to create denser, more social suburban neighborhoods. Garages have scooted discreetly to the sides of the houses, and modest verandas frame the front doors. Yet some of these porches are so small they are really just covered entry ways. Some have been left completely unfurnished, not even pretending to fulfill a greater social function. Others had dreamed once of becoming container gardens, but have degraded instead into gardening sheds, complete with fertilizer bags, muddy trowels, and tangled hoses. Many porches serve as storage units for bikes, strollers, and scooters—second garages for secondary vehicles. The most successful porches are those that form an L. The side piece, served by an additional doorway and set back from the street, is more likely to shelter a cluster of furniture (although I have seen no one sitting there).

Unlike the voluptuous verandas of older houses, new porches are often too skinny to seat a real gathering, let alone a broken washing machine. As for leisure, people may mingle more freely at the local café or in common areas like the park or the pool than in front of their houses. And if television first drew people off the veranda and into the living room, the Internet has social charms that no sidewalk can provide. Facebook is the new front porch.

Along with balconies the size of window boxes and driveways paved like patios, these narrow newcomers may prove to be more a symptom of gas-and-electric life than a solution to it. Still, some people actually do use their porches. One Santa Monica friend reports using her porch as a smoking gallery and overflow space during parties. Another friend, who lives in a New Urban development outside Indianapolis, is never bored on her porch; she brings her wireless laptop outside with her.

Landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing taught Americans how to grow porches around their houses like vines.

Andrew Jackson Downing (1815—1852) popularized the rural cottage, and with it the porch, as the signature of American vernacular housing. According to Downing, the porch invites, prepares, and shelters the visitor. A country house without a porch, he declared, is like a “book without a title page, leaving the stranger to plunge in medias res, without the friendly preparation of a single word of introduction.” Trained as a landscape gardener in the picturesque style, Downing treated the porch as an ornamental, organic form that could wind around and knit together the straight angles of the building, while also opening the inside to the outside, the cottage to its garden.

Downing promoted the rural cottage for middle-class home owners through his widely distributed pattern books. Architect and urban planner Christopher Alexander reinvented the pattern idea in his 1977 text, A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. This thick little volume recalls the pattern books of yore; designed to travel easily between classrooms and construction sites, Alexander’s book features dense pages of old-fashioned typography peppered with tiny black and white drawings.

For Alexander, a pattern is not a floor plan, but rather a connecting principle that links up places and populations via physical behaviors and activities. Patterns such as “old people everywhere,” “accessible green,” and “local sports” profess the value of mixed use, diverse populations, and neighborhood networks. While building a house means considering the surrounding locale, creating a kitchen mobilizes such patterns as “eating atmosphere,” “pool of light,” and “child caves.” The house is a node, not a thing, a moment in a flow of people, goods, and actions that ultimately connects us all.

“People are different sizes; they sit in different ways … . Never furnish any place with chairs that are identically the same.”—Christopher Alexander, 1977 Drawing by Jennifer Tobias

So, too, for Alexander a porch is not a thing added to a house as a pocket or collar might be attached to a dress. Instead, a successful porch brings together a cluster of social uses and habits. The porch is composed of such patterns as “private terrace on the street,” “sunny place,” “outdoor room,” “raised flowers,” and “different chairs.” Out of these patterns, something we might call “porchness” takes shape, involving elements of openness, enclosure, shade, a relationship to the road, and some places to sit.

A few deeply practical tips come out of Alexander’s analysis, such as the dictum that if a porch is really an outdoor room, it should be at least six feet deep, to accommodate a small table and chairs. (Neo-porches, on the other hand, are often skinny appendages or inflated facades that barely afford a bench.) The porch is also a conversation with the neighborhood—it’s not strictly private, but communicates with passersby. There is an economy to Alexander’s pattern poetry: if you put pots of flowers on your porch, you might not need them elsewhere. And if the front porch functions as a terrace on the street, you may not yearn for a patio out back.

I asked a friend from the next block, a sexy scientist from Argentina, how she uses her new porch. “I don’t actually sit out there,” she said, “but it’s great for package delivery. You know”—her voice dropped into a confidential quiver—“from Victoria’s Secret and Frederick’s of Hollywood.” I am glad that the neo-porch is enhancing the sex lives of working mothers, but it hasn’t yet revived the social world framed by its historic ancestors. Maybe I shouldn’t feel so bad about not having a porch. Perhaps all I need is a new blog, a raspberry frappuccino, or a Really Special Delivery. JL

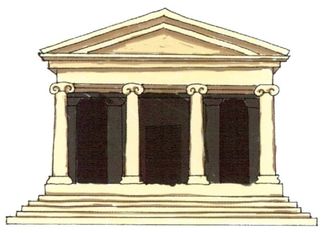

The porticos of antiquity fronted public buildings. In Africa, porch-like structures provided shelter from sun and insects, while opening onto a shared common area. The American house porch is an amalgam of European, African, and Indian imports. Killed by television, air-conditioning, and the garage, the porch has been revived by New Urbanism. Garages have shifted to the sides of the houses, and modest verandas now frame the front doors of many new homes. Yet these under-used add-ons may be more symbolic of social activity than truly a habitat for it.

500 BC GREEK STOA The Greek stoa was a colonnade around a temple. Later, colonnades were used in front of civic buildings, for conducting business in public. The columns offered transparency before the witnessing citizens. The Roman portico served a similar function.

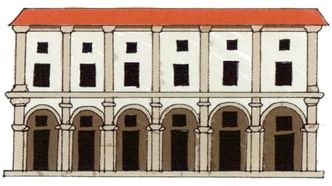

1433 FLORENTINE PALAZZO The loggia, following the Greek stoa and Roman portico, was initially associated in the Renaissance with public buildings. On commercial streets, loggia protected and unified the sidewalk in front of ground floor storefronts, creating the first pedestrian malls.

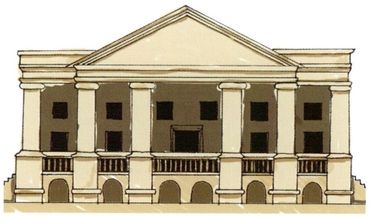

1570 PALLADIO’S LOGGIA Palladio adopted the loggia for the villas of aristocrats, its first major domestic use—but by no means a vernacular one (unlike the American porch).

1500 EUROPE-INDIA CONTACT In India, the veranda is designed to cool the air and provide extra living space. British colonials quickly adopted the idea, creating their own mega-bungalows with verandas.

1650 SLAVE DWELLINGS IN BRAZIL When slaves got off the boat in Brazil, their first job was to erect their own housing. Note the thatched overhang that extends living space into a shared public area.

1880 VICTORIAN FRONT PORCH Steps create distance between the house and sidewalk and elevate the seated homeowner, nurturing a feeling of security.

1985 FRONT PORCH; FRONT GARAGE Porches poured from concrete and hugging the ground are essentially patios with banisters, making easy transitions for strollers, wheelchairs, and drunken guests.

2008 FRONT PORCH; SIDE GARAGE The classic American porch extends most of the length of the facade. Suburban houses in the 1970s and 80s made the garage the most prominent feature of the house. Today, porches are coming back. But what are they really used for?

CRAVING THE BUZZ It’s not just the coffee that’s addictive; it’s the comfort of strangers.